Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with limited treatment options. Melissa officinalis (M. officinalis), traditionally used for its medicinal properties, contains compounds that may offer therapeutic benefits for AD. We extracted essential oils from M. officinalis using supercritical CO2 and identified 31 compounds via GC–MS, supplemented by 20 non-volatile compounds from the Dictionary of Natural Products. Molecular docking was performed against five AD-related targets: β-Secretase, γ-Secretase, amyloid-β) A(, neprilysin, and acetylcholinesterase. The oil’s antioxidant capacity and cytotoxicity on PC12 cells were evaluated using DPPH and MTT assays, respectively. Docking analysis revealed that sajerinic acid had the highest affinity for acetylcholinesterase, neprilysin, and γ-Secretase. Aβ and β-Secretase were most affected by 3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone, 3′-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside, γ-O-β-D-glucopyranoside and 2,3,19,23-tetrahydroxy-12-ursen-28-oic acid-23-sulfate, 28-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester, respectively. Among oil compounds, triethyl citrate showed the highest affinity for β-Secretase, neprilysin, and γ-Secretase, while 2,2-dimethoxybutane exhibited the highest potential for interaction with Aβ and acetylcholinesterase. The oil reduced PC12 cell survival in a dose-dependent manner. The extract also displayed significant antioxidant activity, suggesting a potential to reduce oxidative stress. These findings suggest that M. officinalis contains compounds with potential anti-Alzheimer’s properties, warranting further investigation. The identified compounds could serve as leads for developing novel therapeutics, and the antioxidant activity of the extract supports its traditional use in managing neurodegenerative conditions. Further studies are needed to validate these findings in vivo and explore the therapeutic potential of M. officinalis in AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive brain disorder where harmful proteins build up, leading to brain cell damage and often coinciding with blood vessel issues. It can remain hidden for 20–30 years before clear symptoms appear. The number of people affected is expected to rise, with a predicted 139 million cases worldwide by 20501. Because of the subtle early signs, about 75% of dementia cases go undiagnosed, especially in lower-income countries. Identifying individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or early AD is now more important than ever. Current diagnosis involves cognitive tests and imaging to assess brain changes, highlighting the role of brain scans in managing MCI and AD2,3. AD is characterized by distinct pathological features, primarily the buildup of extracellular plaques composed of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, resulting from the misprocessing of its precursor protein, the amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Two main proteolytic pathways process APP, In the non-amyloidogenic pathway, α-secretase cleaves within the Aβ sequence, releasing soluble amyloid precursor protein-α (sAPPα) and precluding Aβ generation. In the amyloidogenic pathway, β-secretase first produces soluble amyloid precursor protein-β (sAPPβ) and a membrane-bound C99 fragment (C99), which is subsequently cleaved by the γ-secretase complex to release Aβ peptides (Aβ40 and Aβ42). The subcellular localization of these secretases strongly influences Aβ production, with β-secretase and γ-secretase activity in endosomal compartments being critical to amyloid pathology4,5. Melissa officinalis(M. officinalis), a member of the Lamiaceae, is renowned for its traditional uses such as stress reduction, sleep improvement, mood elevation, and concentration enhancement6. M. officinalis is traditionally valued for its calming effects, with modern research confirming its efficacy in reducing anxiety and improving sleep quality. This plant also exhibits potent antioxidant, antiviral (notably against herpes simplex virus), and digestive benefits. These multifaceted properties render M. officinalis a significant subject in herbal medicine research, warranting further investigation into its clinical applications for stress management, neuroprotection, and immune support7,8.

Research suggests M. officinalis could help people with early AD. A clinical trial found that taking M. officinalis extract for four months resulted in significant cognitive improvements9. Beyond its potential effects on specific brain targets, M. officinalis offers antioxidant, anti-anxiety, and antidepressant benefits that could be helpful in Alzheimer’s management10. Also, M. officinalis extract showed strong neuroprotective properties against oxidative damage caused by Aβ by having compounds with antioxidant activity11. These effects were attributed to terpenoic acids and polyphenolic compounds, with a relatively minor role of cholinesterase inhibition12. AD is characterized by the buildup of abnormal protein deposits in the brain. Imagine sticky clumps of a protein called Aβ forming outside of nerve cells—these are amyloid plaques. Inside the nerve cells, another protein, tau, twists and tangles into structures called neurofibrillary tangles. These plaques and tangles act like roadblocks, hindering the delicate communication network between nerve cells. As the disease progresses, these blockages can lead to the destruction of nerve cells, especially those responsible for producing a vital brain chemical called acetylcholine. This disruption of acetylcholine signaling is a major factor in the worsening symptoms of AD13,14. Cholinesterase inhibitors can slow down the breakdown of acetylcholine (ACh), consequently enhancing the accessibility of ACh. The γ-Secretase enzyme is present on the cell surface and completes the function of alpha-Secretase in processing the APP molecule. γ-Secretase is also located in endosomal compartments and enhances the function of β-Secretase in processing the APP molecule in these membranes15,16,17. The amyloidogenic pathway in AD pathogenesis critically involves sequential proteolytic processing of the APP. β-Secretase initiates this pathway by cleaving APP to generate soluble APPβ and a membrane-bound C99 fragment. γ-secretase then processes C99 to release Aβ peptides, particularly neurotoxic Aβ42. Counteracting this process, neprilysin (NEP) functions as the primary Aβ-degrading enzyme, clearing extracellular Aβ aggregates. While acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is classically recognized for hydrolyzing acetylcholine at synapses, it also accelerates Aβ fibril formation and deposition. Thus, dysregulation of these targets—whether through elevated β-Secretase/γ-secretase activity, reduced NEP function, or AChE-mediated Aβ aggregation directly promotes amyloid plaque pathology18,19. NEP, a glycoprotein located on the cell membrane and belonging to the neutral zinc metalloendopeptidase family, acts as a critical enzyme in the degradation of Aβ peptides. NEP can degrade not only the monomer form, but also the oligomeric forms of Aβ1-40. However, NEP levels decrease as people age, leading to an increase in Aβ accumulation20. Low levels of NEP, reduced activity, or genetic changes in the NEP gene correlate with an increased risk of AD. In an AD mouse model, enhanced NEP activity resulted in better outcomes in behavioral assessments, suggesting that interventions that enhance NEP expression or activity can protect against AD21. The application of antioxidant elements in treating AD is centered on the theory of safeguarding neurons. The heightened generation of free radicals due to oxidative metabolism could worsen the observed neuronal damage in Alzheimer’s. In AD, oxidative stress is believed to be initiated by a surplus of oxygen free radicals and the accumulation of extracellular Aβ deposits, which may result in reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation22. In a study that examined the influence of agonists and antagonists of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) on AChE expression in PC12 cells, obtained results indicated that Aβ protein significantly upregulated AChE levels. Notably, Aβ acts as a partial antagonist of α7 nAChRs, and this receptor-mediated antagonism may contribute to its observed induction of AChE overexpression. Critically, nAChR ligands altered AChE expression, suggesting that downstream signaling pathways regulate the enzyme’s biosynthesis23. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of bioactive compounds derived from M. officinalis on five key molecular targets implicated in AD pathogenesis: the β-Secretase, γ-secretase, AChE, and NEP, as well as the Aβ peptide, using computational molecular docking.

Experimental

Chemicals and procedures

GC–MS analysis was performed utilizing a gas chromatography system (model 6890 integrated with a mass spectrometer model 5973N from Agilent Co, USA). Molecular modeling investigations were performed using the Maestro molecular modeling platform (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY; version 10.5; available at: https://www.schrodinger.com/platform/products/glide/). The PC12 cell line used for MTT analysis was purchased from the Pasteur Institute in Iran. This cell line, derived from a pheochromocytoma tumor of rat adrenal medulla, serves as a model for neuronal cells. Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and methanol (99.9% purity) were provided by Merck Co, Darmstadt, Germany. Hexane (99.0% purity) was also purchased from Samchun Chemical Co., Ltd., Korea. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), tetrazolium bromide (MTT), DMEM culture medium, bovine serum, and MTT kit were all purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. Absorbance values were obtained by a microplate reader (Dena, Iran) and a spectrophotometer (Pharmacia model Novaspec II).

Plant materials and extraction

M. officinalis was collected from the Kashan area (Kashan, Iran) in spring 2024; the plant was cultivated, not wild, and identified by Dr. Toloui. Voucher specimen (University of Kashan Herbarium (UKH) 2880) was deposited in the herbarium of the University of Kashan. For extraction, leaves were desiccated at ambient temperature and pulverized with a mechanical grinder. 1 g of it was weighed on a scale and entered into a reactor (made of stainless steel 316 and with a volume of 60 mL) along with 20 g of dry ice and 3 mL of methanol. The pressure and temperature set to 40 bars and to 65 ⁰C, respectively. After 30 min, the extraction process was completed. In this setup, the plant-to-solvent ratio was approximately 1:20 (w/w). Liquid CO2 generated from dry ice was used as the primary solvent, while methanol (3 mL) acted as a co-solvent to enhance the recovery of polar constituents. The extraction was performed under static conditions for 30 min, after which the pressure was gradually released. The choice of 40 bar and 65 °C ensured that CO2 remained in the supercritical state, with low viscosity and high diffusivity, facilitating better penetration into the plant matrix compared to conventional hydrodistillation. These parameters were optimized based on preliminary tests to balance extraction yield and compound stability. The contents inside the reactor were collected using methanol, and then centrifuged and filtered to separate the extract from the plant residues.

GC–MS analysis

The extract was analyzed utilizing an Agilent GC–MS instrument. The identification of compounds was carried out using GC retention indices from C6 to C24. The constituents in the extract were recognized by matching their mass spectra against various databases, including those from Wiley, NIST, and the Adams Mass Spectral library. Additionally, retention indices were compared with published literature values for further validation24. Quantification of components is based on relative surface percentages obtained from GC analysis.

Molecular docking (MD)

MD analysis was performed using the Glide application within the Schrodinger platform. Structure of the identified compounds was drawn in ChemDraw application and then imported to the Ligand Preparation module of the Schrodinger package to optimize them in terms of length and bond angles. The structures of five AD-related targets (acetylcholinesterase, γ-secretase, β-secretase, neprilysin, and the Aβ peptide) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org). The targets were refined by eliminating the crystallized ligands and all free water molecules, followed by energy minimization with the protein preparation tool in Maestro 10.6. Grid boxes of the 5 overmentioned targets were also determined based on their default ligands or using their coordinates reported in the literature. The illustrated center coordinates of the grid box are X: − 2.4700 Å, Y: − 0.0652 Å, Z: 1.2694 Å for Aβ (pdb code: 1IYT); X: 172.84 Å, Y: 175.61 Å, Z: 187.71 Å for γ-Secretase (pdb code: 6IYC); and X: 54.23 Å, Y: 62.81 Å, Z: 60.85 Å for β-Secretase (pdb code: 1FKN) which obtained from the previous reports25,26,27 and X: 2.7174 Å, Y: 64.5516 Å, Z: 68.0021 Å for acetylcholinesterase (pdb code: 1EVE) and X: − 14.601 Å, Y: − 19.893 Å, Z: − 31.564 Å for neprilysin (pdb code: 5JMY) which was determined based on the position of their default ligands. Molecular docking analysis was carried out in Glide software of the Schrodinger suit at an Extra Precision (XP) mode. The compound Galantamine was utilized as the positive control in this study.

Free radical scavenging activity

A colorimetric method evaluated the free radical scavenging potential of M. officinalis extract against DPPH radicals. Specifically, 25 mg extract was dissolved in 25 mL methanol. Then, it was diluted in different ratios to give concentrations of 0.8, 0.5, 0.25, 0.1, 5 × 10⁻2, 5 × 10⁻3, 5 × 10⁻4 mg/mL. After that, a 0.1 mg/mL DPPH was prepared in methanol. Then, the samples at various concentrations, DPPH solution and methanol were mixed at a ratio of 1:2:2, respectively. Discoloration of the mixtures was measured at 517 nm after half an hour. The inhibition percentage for each concentration was determined using the formula below.

% Inhibition = [(control absorbance—sample absorbance) / control absorbance] × 100.

The findings were expressed as IC50, indicating the concentration of the extract needed to eliminate 50% of the DPPH radicals28.

Cell culture and MTT assay

The effect of M. officinalis extract against the cell viability of PC12 cell line was investigated using a MTT assay. For this, PC12 cells, which possess neuronal growth factor enzymes, were grown in a nutrient-dense medium that included antibiotics. They were incubated at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide and a humidity level of 95%. Regular passaging into fresh culture flasks was performed, with medium changes occurring every three days. PC12 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well and and allowed to grow until they reached 90–95% confluence (90–95%)29. Each well received 100 μL of culture medium containing varying concentrations of extract, ranging from 31.2 to 4000 μg.mL−1. After a whole day incubation, 20 μL of MTT solution was added to wells and incubated for 4 h. Subsequently, the culture medium was discarded, and 200 μL of DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the formazan. The absorbance for each well was subsequently assessed at a wavelength of 570 nm using an ELISA reader. Each data point represents the mean ± standard deviation of three independent biological replicates (n = 3). The viability percentage of the cells was determined using the equation below:

“Absorbance of sample” refers to wells containing cells, extract, and MTT reagent.

“Absorbance of control” refers to wells containing cells and culture medium (without extract) treated with MTT reagent.

“Absorbance of blank” refers to wells containing culture medium and DMSO (without cells) to account for background absorbance from the medium and the solvent used to dissolve the formazan crystals.

To determine IC50, which indicates the extract concentration that decreases cell viability by 50%, a linear regression analysis was employed. The equation was:

Y represents 50% of cell viability; − 0.0167 and 75.018 are values obtained from the viability plot.

Results and discussion

The extract composition

The essential oil was analyzed using GC–MS (Fig. 1), which led to the identification of 31 compounds (Table 1), among which three compounds octadecane (20.75%), 6,7,9,10-bisepoxy nonadecane (10.41%), and glycerol, 2-tetradecanoate, diacetate (9.21%) were the major constituents of the oil. Additionally, 20 other non-volatile compounds were identified from literature via a search in Dictionary of Natural Products (DNP) database; making a total of 51 compounds in the plant. All these compounds were further used for molecular docking analyses.

Various analyses have been performed on identification of the metabolites of the oil of M. officinalis. Sodré et al., reported 16 compounds derived from the GC–MS of M. officinalis extract. They were pentyl propanoate, 3-octanone, myrcene, cis-β-ocimene, linalool, perylene, citronellal, isomentol, β-citronellol, neral, geraniol, methyl citronellate, geranial, methyl geranate, geranyl acetate, and β-caryophyllene30. In another study, 30 compounds were identified for the essential oil of M. officinalis obtained through water distillation using a Clevenger device with the help of GC–MS analysis. The major components included citronellal (36.62–43.78%), β-citronellol (10.10–17.43%), thymol (0.40–11.94%), and β-caryophyllene (5.91–7.27%)31. Further investigation into the chemical composition of dried M. officinalis leaves, determined that terpenes were the primary compounds (15 monoterpenes at 71.91%, and 8 sesquiterpene compounds at 19.01%). Among the identified compounds, citronellal (27.54%), α-citral (25.00%), β-caryophyllene (2.24%), and β-citronellol (7.61%) were the major components of oil. Additionally, 11 aldehyde compounds (3.64%), 6 alcohols (3.60%), 4 ketones (0.96%), and 3 esters (0.76%) were identified32. Considering that diffusion in a supercritical environment is much faster than in other methods, extraction can occur more rapidly. Furthermore, due to the negligible surface tension and viscosity compared to liquids, the solvent can penetrate more deeply into the inaccessible matrix of liquids. For this reason, this study resulted in discovery of new compounds in the extract of M. officinalis that had not been mentioned in previous reports. It is important to mention that among the compounds mentioned in other articles, the common compounds caryophyllene (2.06%), β-citronellol (0.64%) and several other hydrocarbons (43.9%) were also present in our extract. Interestingly, the essential oil profile obtained in this study is atypical compared to most literature reports on M. officinalis. Whereas previous studies frequently reported monoterpenes such as citronellal, geraniol, and β-citronellol as dominant constituents, our extract was characterized by a high proportion of alkanes (43.9%), including octadecane and nonadecane. Such variations may arise from the extraction methodology, as supercritical CO2 conditions (40 bar, 65 °C) differ significantly from hydrodistillation, leading to enhanced recovery of non-polar hydrocarbons. Additionally, environmental and cultivation factors such as soil composition, harvest time, and geographical conditions may further contribute to these chemical differences.

Antioxidant activity

Antioxidants are acknowledged for their vital function in protecting the body from ailments caused by oxidative damage. Production of ROSs can surpass the cellular defenses provided by antioxidants, resulting in a state known as oxidative stress. This phenomenon is particularly significant as it is associated with the onset and advancement of various degenerative diseases through mechanisms such as protein oxidation, and lipid peroxidation. Numerous studies have demonstrated the participation of ROS and oxidative stress in a range of health issues, including diabetes, heart-related conditions, and long-term neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson and AD, among others33. M. officinalis contains a wide range of antioxidant compounds, including phenolic acids (such as rosmarinic acid), flavonoids, and terpenes34. This makes the plant as a valuable ingredient for promoting overall health, and it could have potential applications in both food and pharmaceutical industries35.

Antioxidant activity is primarily mediated by compounds with conjugated double-bond systems or phenolic hydroxyl groups, which donate electrons or hydrogen atoms to stabilize reactive free radicals. In the case of M. officinalis essential oil, composed predominantly of hydrocarbons, esters, alcohols, and acids, antioxidant effects likely arise via these mechanisms, where structurally applicable36.Among the compounds identified from GC–MS analysis, compounds such as: Caryophyllene (MO5) with a conjugated ring system, alpha-Humulene (MO7) with multiple double bonds, Triethyl citrate (MO11) with a phenyl group (benzene ring) and Oleic acid (MO23), a fatty acid with double bond, can provide antioxidant activity. 6,7,9,10-Bisepoxynonadecane (MO29) is a unique structure with two epoxy groups, which could contribute to antioxidant activity. Among the non-volatiles, compounds that have hydroxyl groups (-OH) in their structure, as well as polyphenolic and flavonoid compounds such as 3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-2-hydroxypropanoic acid; (R)-form, 2-O-(3,4-dihydroxy-E-cinnamoyl) (MO-46), Salvianolic acid I 8″Z-Isomer (MO-41), and 3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone 3′-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside, γ-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (MO-33) have potential antioxidant properties. These non-volatile compounds, from the Dictionary of Natural Products, are cataloged in Supplementary Table (Table S1).

So, we used DPPH radicals to investigate the free radical neutralizing potential and antioxidant capacity of the extract. Obtained results showed a high antioxidant activity for the extract with an IC50 value of 71 μg.mL−1 in comparison with the IC50 value of 386.42 μg.mL−1 for BHT as the positive control (Fig. 2), indicating a good candidate for applying it as an anti-oxidant.

Determination of cell viability with MTT analysis

This research evaluated the effect of M. officinalis extract on the viability of PC12 cells through an MTT assay. The findings indicated that the extract decreased cell viability in a dose-dependent fashion, yielding an IC50 value of 630 µg.mL−1 (Fig. 3). Comparison of the results of MTT and DPPH tests indicated that at the IC50 concentration of antioxidant activity (71 µg.mL−1), the effect of the essential oil on PC12 cell death was very low. It may be concluded that the oil can control Alzheimer’s disease by inhibiting oxidative stress with no significant lethality on PC12 nerve cells, whose existence is essential for the body. These findings can be used as a basis for further research on the potential therapeutic effects of M. officinalis essential oil. However, the MTT assay primarily reflects cell viability and does not directly demonstrate neuroprotective or anti-Alzheimer’s activity. Although the extract demonstrated antioxidant activity and relatively low cytotoxicity at moderate concentrations, these results should be interpreted cautiously. Additional neuroprotection-specific assays and in vivo studies are required to validate any potential therapeutic claims.

Molecular docking results

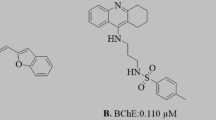

Molecular docking analysis of all identified compounds was carried out against five targets involved in the creation of Alzheimer’s disease using the Schrodinger suite. Galantamine was also used as the positive control. A scoring function of docking score values was used to predict the binding affinity between ligands and targets upon docking. Several compounds indicated more affinity to different targets in comparison with the positive control resulting a high potential of M. officinalis for controlling the effective factors in causing of Alzheimer disease. Docking scores of − 2.556, − 1.960, − 2.363, − 2.994, − 3.761 kcal/mol were obtained for galantamine against Aβ, acetylcholinesterase, β-Secretase, γ-Secretase, neprilysin, respectively. However, sagerinic acid (MO-32) exhibited the highest affinity against neprilysin, γ-Secretase and acetylcholinesterase with docking scores of − 14.586, − 9.900 and − 7.320 kcal/mol, respectively. Also, Aβ and β-Secretase had the best affinity to 3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone, 3′-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside, γ-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (MO-33) and 2,3,19,23-tetrahydroxy-12-orsen-28-oic acid-23-sulfate, 28-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester (MO-34), with docking score values of − 6.048 and − 7.136 kcal/mol, respectively. The promising docking results observed for sagerinic acid and MO-33/34 correspond to compounds sourced from the DNP database rather than the crude oil extract. As such, the docking and in vitro assays provide complementary but not directly connected insights into the potential of M. officinalis. Among the compounds of the oil extracted via a SFE, Triethyl citrate (MO-11) was the most active ligand against neprilysin, γ-Secretase and β-Secretase with docking scores of − 4.622, − 3.108 and − 1.118 kcal/mol, respectively. Also, acetylcholinesterase and Aβ were mostly affected by 2,2-dimethoxybutane (MO-1) with docking scores of − 3.080 and − 2.17 kcal/mol, respectively. A view of the best docked ligands against evaluated targets have been shown in Fig. 4. According to the findings and considering that M. officinalis is traditionally used for treatment of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s, it can be inferred that the oil of M. officinalis may inhibit the breakdown of APP protein by inhibiting β-Secretase and γ-Secretase. Additionally, by binding the bioactive compounds of the plant to Aβ, the oil may inhibit its functional activity, preventing the formation of amyloid plaques in brain vessels. Moreover, by Agonist neprilysin secreted from brain cells called astrocytes, it leads to the breakdown of Aβ. It should be noted that docking against Aβ (PDB: 1IYT) represents only a static snapshot of this highly dynamic peptide. Therefore, the results must be interpreted cautiously. Molecular dynamics simulations would provide more biologically relevant insights and are suggested for future work.

2D and 3D view of the best docked ligands against Alzheimer’s disease targets; a: amyloid-β interaction with 3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone, 3′-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside, γ-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, b: β-Secretase interaction with 2,3,19,23-tetrahydroxy-12-orsen-28-oic acid-23-sulfate, 28-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester; & c, d, e: γ-Secretase, acetylcholinesterase and neprilysin interaction with sagerinic acid, respectively. This figure was generated using Schrodinger’s Maestro molecular modeling software (version 2022.4).

While molecular docking indicated favorable binding of certain compounds from M. officinalis oil to Alzheimer’s-related targets, docking cannot establish whether these interactions inhibit or activate the enzymes. Therefore, our findings should be regarded as preliminary evidence of binding affinity, requiring validation through molecular dynamics simulations and experimental studies.

Conclusion

This study was conducted to assess the biological and anti-Alzheimer’s properties of the oil and chemical compounds derived from M. officinalis. Our findings showed that the compounds present in M. officinalis are very effective in inhibiting of involved factors in AD. Overall, this plant prevents the formation of brain plaques in nerve cells. Through this study, we also discovered high antioxidant properties of this plant as well as its good performance against PC12 cells in MTT test. As a result, the compounds of M. officinalis extract showed potential applications in medicine and pharmacology for treatment of various diseases, especially Alzheimer’s.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

References

Gauthier, S. et al. World Alzheimer report 2021: Journey through the diagnosis of dementia 2022 (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2021).

Sorby-Adams, A. J. et al. Portable, low-field magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 1–12 (2024).

Memudu, A.E., B.A. Olukade, and G.S. Alex, Neurodegenerative Diseases: Alzheimer’s Disease. Integrating Neuroimaging, Computational Neuroscience, and Artificial Intelligence: p. 128–147.

Vassar, R. Bace 1: The β-secretase enzyme in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 23(1), 105–113 (2004).

De Strooper, B., Iwatsubo, T. & Wolfe, M. S. Presenilins and γ-secretase: Structure, function, and role in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2(1), a006304 (2012).

Petrishina, N., et al., Comparative anatomical and morphological characteristics of two subspecies of Melissa officinalis L.(Lamiaceae) (2022).

Kennedy, D. et al. Modulation of mood and cognitive performance following acute administration of single doses of Melissa officinalis (Lemon balm) with human CNS nicotinic and muscarinic receptor-binding properties. Neuropsychopharmacology 28(10), 1871–1881 (2003).

Üstündağ, Ü. et al. Effect of Melissa officinalis L. leaf extract on manganese-induced cyto-genotoxicity on Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 22110 (2023).

Akhondzadeh, S. et al. Melissa officinalis extract in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 74(7), 863–866 (2003).

Zam, W. et al. An updated review on the properties of Melissa officinalis L.: Not exclusively anti-anxiety. Front. Biosci. Scholar 14(2), 16 (2022).

Abo-Zaid, O. A. et al. Melissa officinalis extract suppresses endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in the brain of hypothyroidism-induced rats exposed to γ-radiation. Cell Stress Chaperones 28(6), 709–720 (2023).

Shah, F. H. et al. Neuroprotective and nootropic evaluation of some important medicinal plants in dementia: A review. Lett. Drug Des. Discovery 21(10), 1652–1661 (2024).

Kamble, S. M., Patil, K. R. & Upaganlawar, A. B. Etiology, pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and amyloid beta hypothesis. In Alzheimer’s Disease and Advanced Drug Delivery Strategies 1–11 (Elsevier, 2024).

Walker, L.C., Aβ plaques. Free Neuropathology (2020).

Akbarabadi, P. & Pourhosseini, P. S. Alzheimer’s disease: Narrative review of clinical symptoms, molecular alterations, and effective physical and biophysical methods in its improvement. Neurosci. J. Shefaye Khatam 11(1), 105–118 (2022).

Firdoos, S. et al. In silico identification of novel stilbenes analogs for potential multi-targeted drugs against Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Model. 29(7), 209 (2023).

Kim, B.-S. et al. EBP1 potentiates amyloid β pathology by regulating γ-secretase. Nat. Aging 5, 486 (2025).

Lee, M. et al. Rapamycin cannot reduce seizure susceptibility in infantile rats with malformations of cortical development lacking mTORC1 activation. Mol. Neurobiol. 59(12), 7439–7449 (2022).

Zhao, Y. et al. β2-Microglobulin coaggregates with Aβ and contributes to amyloid pathology and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Nat. Neurosci. 26(7), 1170–1184 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Research article reduced expression of voltage-gated sodium channel Beta 2 restores neuronal injury and improves cognitive dysfunction induced by Aβ1–42. Neural Plast. 2022, 3995227 (2022).

Martins, J. E. R. et al. Computational insights into the interaction between neprilysin and α-Bisabolol: Proteolytic activity against beta-amyloid aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease. Processes 12(5), 885 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. Interface potential-induced natural antioxidant mimic system for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Commun. Chem. 7(1), 206 (2024).

Ranglani, S. et al. A novel peptide driving neurodegeneration appears exclusively linked to the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Mol. Neurobiol. 61, 8206 (2024).

Said-Al Ahl, H. A. et al. Essential oil content and concentration of constituents of Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis L.) at different harvest dates. J. Essent. Oil Bearing Plants 21(5), 1410–1417 (2018).

Kumar, V. N. et al. In silico study of traditional Chinese medicinal compounds targeting alzheimer’s disease amyloid beta-peptide (1–42). Chem. Phys. Impact 7, 100383 (2023).

Borah, K., Sharma, S. & Silla, Y. Structural bioinformatics-based identification of putative plant based lead compounds for Alzheimer Disease Therapy. Comput. Biol. Chem. 78, 359–366 (2019).

Jabir, N. R. et al. Concatenation of molecular docking and molecular simulation of BACE-1, γ-secretase targeted ligands: In pursuit of Alzheimer’s treatment. Ann. Med. 53(1), 2332–2344 (2021).

Rădulescu, M. et al. Chemical composition, in vitro and in silico antioxidant potential of Melissa officinalis subsp officinalis essential oil. Antioxidants 10(7), 1081 (2021).

Ranjan, S. et al. The effect of Psoralea corylifolia (Babchi) on neuronal apoptosis induced by palmitate in PC12 cells and its role in Alzheimer’s disease: A review. Pharmacogn. Mag. 21, 7–26 (2024).

Sodré, A. C. B. et al. Organic and mineral fertilization and chemical composition of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) essential oil. Rev. Bras 22, 40–44 (2012).

Cosge, B., İpek, A. & Gürbüz, B. GC/MS analysis of herbage essential oil from lemon balms (Melissa officinalis L.) grown in Turkey. J. Appl. Biol. Sci. 3(2), 149–152 (2009).

Ieri, F. et al. HPLC/DAD, GC/MS and GC/GC/TOF analysis of Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) sample as standardized raw material for food and nutraceutical uses. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 31(2), 141–147 (2017).

Dos Santos, N. C. L. et al. Antioxidant and anti-Alzheimer’s potential of Tetragonisca angustula (Jataí) stingless bee pollen. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 308 (2024).

Petrisor, G. et al. Melissa officinalis: Composition, pharmacological effects and derived release systems—A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(7), 3591 (2022).

Kera, V. et al. Melissa officinalis: A review on the antioxidant, anxiolytic, and anti-depressant activity. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res. Asia 21(2), 491–500 (2024).

Adamczyk-Szabela, D. et al. Antioxidant activity and photosynthesis efficiency in Melissa officinalis subjected to heavy metals stress. Molecules 28(6), 2642 (2023).

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Atiyeh Kolouei; Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft Mohammad Barati; Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration Mahdi Abbas-Mohammadi; Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolouei, A., Barati, M. & Abbas-Mohammadi, M. Investigating the binding potential of the Melissa officinalis oil against Alzheimer’s targets by molecular docking and in vitro evaluations. Sci Rep 16, 736 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30232-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30232-w