Abstract

Accelerometer data are commonly reduced into epoch summary measures (ESMs) for analysis, e.g. ENMO (Euclidean Norm Minus One), MAD (Mean Amplitude Deviation), MIMS (Monitor Independent Movement Summary) or Counts. We compared associations with all-cause mortality of the volume and intensity of physical activity when derived from those four measures in the Whitehall II and UK Biobank cohorts. Volume (Average Acceleration, AvAcc) and intensity (Intensity Gradient, IG) were derived from each ESM. Associations with mortality were estimated using Cox models. 3733 (25.1% female, median age 68.3 years) and 89,848 (56.4% female, 63.5 years) participants were included from Whitehall II and UK Biobank, respectively. Median (IQR) follow-up was 11.0 (10.7, 11.3) and 8.0 (7.5, 8.5) years, with 563 (15.1%) and 3656 (4.1%) deaths. Associations with mortality were largely consistent between ESMs with the lowest mortality risk for those high (above the median) in both AvAcc and IG (Whitehall: HR = 0.59–0.68; Biobank: 0.55–0.61, reference: low/low), and IG associated with lower mortality risk, irrespective of AvAcc. AvAcc was associated with lower mortality irrespective of IG in Biobank only. In conclusion, associations of AvAcc and IG with mortality are broadly consistent across common ESMs, supporting comparability of activity-health findings across studies using different ESMs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 2010, accelerometer-based assessment of physical activity (PA) has become increasingly accessible, even for large-scale studies1, enabling a more detailed understanding of the relationships between PA and health e.g. life expectancy2, incident cardiovascular disease (CVD)3, and all-cause mortality4,5.

Among PA variables, the Average Acceleration (AvAcc) of accelerometer-assessed PA across the day is a proxy for PA volume6, and the Intensity Gradient (IG) describes how PA is accumulated over the day—i.e. mainly at lower or higher intensities7. This combination of PA volume and intensity explains more variance in cardiometabolic risk8, waist-to-height-ratio and metabolic syndrome risk9, incident cardiovascular disease3, and life expectancy2 than either alone.

Accelerometers store high resolution accelerations. These accelerations result not only from movement, but also from gravity and sensor noise. To convert the raw data into meaningful PA variables (e.g., AvAcc and IG), primarily reflecting accelerations due to movement, the acceleration data are processed and summarised into an epoch summary measure (referred to herein simply as “measure”)10. Pre-2010, this processing was carried out on-board the accelerometer and only manufacturer-specific “counts” were available to researchers11. Post-2010, accelerometer manufacturers made the raw accelerations available to researchers who could select from open-source measures, such as the Euclidean Norm Minus One (ENMO)10 or the Mean Amplitude Deviation (MAD)12. The standard variant and a filtered variant of ENMO were used in the German National Cohort Study (NAKO) and UK Biobank13, respectively, with MAD used as a secondary measure in NAKO14, the Monitor Independent Movement Summary (MIMS)15, has been used in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)16, and the ActiGraph Counts algorithm (referred to herein as “Counts”) has been published17.

As diverse measures proliferate, it is critical to know whether PA–health associations hold regardless of measure choice. Recently, Willems et al. showed AvAcc and IG, and their correlation to cardiometabolic health markers, can vary between measures18. This likely relates to key differences and considerations relating to the intrinsic properties of the measures19, with Karas et al. reporting non-linear relationships between commonly used measures20. Further, the IG was originally developed for use with ENMO7. Similarly to Willems et al.,21,22,23 found limited agreement between IGs derived from different measures. However, some improvement was evident following measure-specific adjustments to the IG algorithm to adapt it for use with MAD, MIMS, and Counts23. It is not known whether measure-specific adjustments to IG yield comparable AvAcc-IG-mortality associations across ENMO, MAD, MIMS, and Counts.

This study aimed to compare combined associations of AvAcc and IG with mortality computed from four measures (ENMO, MAD, MIMS, and Counts) in two large cohorts—Whitehall II24,25 and UK Biobank13,26—where combined associations with mortality of PA volume and intensity generated from the ENMO measure have previously been demonstrated2,27. This study is part of the Learning Network for Advanced Behavioural Data Analysis (LABDA)28.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study populations

Established in 1985, the Whitehall II study aims to investigate health inequalities in a cohort of 10,314 British civil servants (6900 men, 3414 women)29. Recurrent data collections have been conducted in the study roughly every five years, with accelerometry added in a subpopulation of 4282 participants in 2012–2013. Written, informed consent from participants was obtained at each contact. Research ethics approvals were renewed at each wave; the most recent approval was granted by the National Health Service (NHS) London-Harrow Research Ethics Committee (reference number 85/0938). Participants wore a GENEActiv (Activinsights Ltd, Cambridgeshire, UK) accelerometer continuously for nine days, sampling at 85.7 Hz, \(\pm\) 8 g (gravitational unit (1 g = 9.81 m/s2)), on their non-dominant wrist24.

UK Biobank consists of 500,000 British participants aged 40–69 recruited in 2006–201026. UK Biobank has full ethical approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (16/NW/0274) and all participants gave written informed consent prior to data collection. Between 2013 and 2016 accelerometry was collected in a subpopulation of 106,053 participants continuously for seven days, employing the Axivity AX3 device (Axivity Ltd, Newcastle, UK), sampling at 100 Hz, \(\pm\) 8 g, worn on the dominant wrist13.

Besides accelerometry, both datasets contain clinical, questionnaire, and health registry linked data, including mortality data26,30.

All procedures and methods conform to the ethical guidelines defined by the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions.

Accelerometer processing

Accelerometer data were initially processed using the R package GGIR31 part 1 with default settings, including autocalibration32, non-wear and clipping detection31 to generate epoch-level data for ENMO, MAD, and Counts in 5 s epochs. Five second epochs were used in the original implementation of the IG7, has commonly been used in comparable analyses2,3,4,5, and has been shown to be more appropriate for use with the IG, compared to longer epochs33. Code recreating relevant steps in GGIR part 1, or calling specific functions within GGIR part 1 where possible, was then applied to generate MIMS using the MIMSUnit R package15 and integrate the output with the GGIR part 1 output to feed into GGIR part 2. In GGIR part 2, invalid data (non-wear or clipping) was imputed using the average of the same point in time across the remaining measurement days per measure. Participants failing calibration (> 0.01 g calibration error7), with fewer than 3 valid days (> 16 h/day) of wear, or where wear-data were not present for each 15-min period of the 24-h cycle, were excluded7.

Epoch summary measures

ENMO is the epoch mean of the vector magnitude of the triaxial acceleration signal, minus 1 g to account for the influence of gravity, with negative values rounded to zero. It is thus a measure of the mean magnitude of acceleration within the epoch10. MAD is likewise based on the vector magnitude but measures the mean absolute deviation from the epoch mean, as opposed to the epoch mean directly12. Counts and MIMS are both derived from more complex algorithms consisting mainly of multiple resampling and filtering steps, meant to account for differences in sampling rate, and/or gravity and signal noise15,17. More details regarding each measure are included in Supplementary Section S1.

Physical activity exposures

AvAcc and IG were generated for each measure per valid 24-h day, using the adjusted bins proposed previously for IG23. Note, Eckmann et al. tested two types of adjusted bins, “modelled” and “naïve”, with the “modelled” approach providing better agreement between measures. Therefore, in our analysis the “modelled” bins were used. AvAcc and IG per participant were each then calculated as the mean of the valid days available for each participant. Participants with AvAcc values, based on ENMO, above 100 mg were excluded from all analyses, including those based on MAD, MIMS, and Counts, as these were considered to be unrealistic, and therefore indicative of errors in the raw acceleration file, consistent with previous UK Biobank analyses34. Additionally, participants above and below the 99.5th and 0.5th percentile, respectively, for either of AvAcc or IG based on ENMO were also excluded from all analyses to limit the influence of outliers. Exclusions were applied for all analyses based on ENMO only to keep the dataset consistent for comparison between measures, and because thresholds for unrealistic values are not available for all of the epoch summary measures considered.

Covariate measurement

Covariates for this analysis included socio-demographic and lifestyle related characteristics of age, sex, ethnicity (white/non-white), education level (low, middle, high), current employment (yes/no), self-reported sleep duration (< 7, 7–8, > 8 h), smoking status (current, former, never), and alcohol consumption (frequency, Whitehall II: never, < 1/month, 2–4/month, 2–3/week, 4+/week; UK Biobank: never, < 1/month, 1–3/month, 1–2/week, 3–4/week, 4+/week). Health-related covariates included body mass index (BMI) (underweight, normal, overweight, obese), number of prescribed medications, prevalent CVD, cancer, and number of other prevalent chronic diseases. Season of accelerometer wear was derived from the start time of the accelerometer recording using two orthogonal sine functions as in Dempsey et al.3

For Whitehall II, covariates were extracted from a clinical screening and questionnaire at the time of accelerometer data collection and imputed with answers from previous screenings/questionnaires where missing. Disease and risk factor covariates were updated if Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data included a diagnosis before accelerometer screening date. For UK Biobank, all participants completed a questionnaire and assessment at recruitment into the main study, with some participants completing two further follow-up questionnaires. Where available, covariate data from the most recent questionnaire before accelerometer assessment were used, and baseline data were used otherwise. Strain et al. showed mostly minor differences between covariates measured at baseline versus later questionnaires4. Sex was only obtained at recruitment baseline, and ethnicity was assumed to be constant. Covariates were kept as consistent as possible between both cohorts, but some differences were unavoidable, details are included in Supplementary Table S1. Participants with missing data were excluded.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was all-cause mortality identified from the UK Office for National Statistics Mortality Register. Participants were censored at time of death or censoring (October 2023 Whitehall II; November 2022 UK Biobank).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and number and percentage (%) for categorical variables.

Relative agreement between measures for AvAcc and for IG was assessed using Pearson’s r. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient35 (ICC, two-way mixed effects model, consistency, single rater) was also estimated for IG only. The ICC is sensitive to differences in both mean and scale between measures35 and would therefore not be a good measure of agreement for AvAcc, as AvAcc inherits scale and unit from a given measure.

Both AvAcc and IG, for each measure, were modelled as natural splines with three internal knots (boundary knots at the 5th and 95th percentile, internal knots at the 25th, 50th and 75th percentile of values within the boundary knots) in mutually adjusted Cox proportional hazards model, and HRs were plotted as a function of each. Linear terms and splines with one through seven internal knots were tested. Linear terms and splines with fewer than three internal knots caused proportionality and/or linearity to fail across several models. More knots uniformly resulted in higher model Bayesian Information Criterion values (Supplementary Figure S1). To be able to compare between measures, both AvAcc and IG were standardised, for each measure, before modelling by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation such that the value represents the number of standard deviations from the mean.

To quantify the combined impact of low versus high AvAcc and IG, for each measure, including interactions between the two, a new categorical variable was created categorising participants into one of four categories based on whether their AvAcc and IG were above or below the median, i.e. low AvAcc and low IG (“low/low”), low AvAcc and high IG, high AvAcc and low IG, and high AvAcc and high IG. This categorical variable was then used as the main exposure in a second Cox model with low/low as reference and hazard ratios (HR) were estimated.

Age was used as the underlying timescale. The main analyses were adjusted for only hypothesised confounders, with an additional sensitivity analysis undertaken to include potential mediators. All socio-demographic and lifestyle covariates were considered confounders, along with season of accelerometer wear. All health-related covariates were considered possible mediators or confounders (Supplementary Figure S2). Proportional hazards and linearity assumptions were checked using Schoenfeld residuals and Martingale residuals respectively; covariates that failed to meet the proportionality assumption were used to stratify baseline hazards. A further sensitivity analysis including only participants aged ≥ 60 at time of accelerometer measurement in UK Biobank was carried out to match the age range to the Whitehall II cohort.

Analyses were replicated in both Whitehall II and UK Biobank and completed using R version 4.3.1. UK Biobank data were processed using ALICE High Performance Computing at the University of Leicester. Results are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All relevant code is available on GitHub at github.com/henrikeckmann.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of 4,210 available accelerometer files for Whitehall II, 3,733 participants were left after exclusions, including 939 (25.1%) women. More details regarding exclusions are included in Supplementary Figure S3. Median age (median (IQR)) was 68.3 (64.7, 73.8), and 3,497 (93.7%) participants were white. Over a median follow-up of 11.0 (10.8, 11.3) years, 563 (15.1%) deaths occurred, 453 (16.2%) in men, and 110 (11.7%) in women.

For UK Biobank, of an initial 115,409, 89,848 participants were left after exclusions, including 50,710 (56.4%) women. Median age was 63.5 (56.3, 68.6) and 87,118 (97.0%) participants were white. Over a median follow-up of 8.0 (7.5, 8.5) years, 3656 (4.1%) deaths occurred, 2188 (5.6%) in men, and 1468 (2.9%) in women. Descriptive statistics for covariates and PA measures are included in Tables 1 and 2.

Relative agreement of AvAcc and IG across ENMO, MAD, MIMS, and counts

Whitehall II

For AvAcc, correlations ranged from 0.79 (CI: 0.78, 0.80) between MIMS and Counts, to 0.98 (0.98, 0.98) between ENMO and MAD (Table 3). The strongest correlation was between ENMO and MAD, while the weakest were when Counts was one of the measures. For IG, patterns for Pearson’s r and ICC were similar. ICCs ranged from 0.59 (0.57, 0.61), between MAD and Counts, to 0.88 (0.88, 0.89), between ENMO and MAD, indicating moderate to good agreement35. Consistent with AvAcc, the strongest correlation was between ENMO and MAD, while the weakest were when Counts was one of the measures.

UK Biobank

For AvAcc, correlations were generally similar to Whitehall II, except for lower correlations for MIMS with ENMO or MAD. Correlations ranged from 0.69 (0.69, 0.70) between MIMS and ENMO, to 0.97 (0.97, 0.97) between ENMO and MAD. As with Whitehall II, the strongest correlation was for ENMO and MAD, however, here the weakest correlations were where MIMS was one of the measures, while in Whitehall II Counts showed the weakest correlations. For IG, patterns for Pearson’s r and ICC were similar. ICCs ranged from 0.60 (0.59, 0.60), between ENMO and Counts, to 0.87 (0.87, 0.87), between ENMO and MAD, indicating moderate to good agreement35. Consistent with AvAcc and Whitehall II, ENMO and MAD had the strongest correlation. Consistent with Whitehall II, but not AvAcc in UK Biobank, Counts showed the weakest correlations with the other measures.

Associations of PA volume and intensity with mortality

Whitehall II

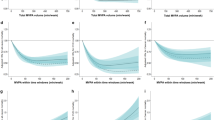

Mortality risk was lower for higher values of AvAcc from ENMO, with a plateau between approximately − 1 to 0 standard deviations (SDs) (Fig. 1a). The pattern from the alternate measures was broadly similar with all CIs overlapping throughout the range, with the pattern for AvAcc from MAD most similar. In contrast to ENMO and MAD, for both Counts and MIMS, the HR tended to be higher between 0 and 1 SDs than either side of the interval.

Hazard ratios for mortality according to (a) AvAcc and (b) IG, from ENMO, MAD, MIMS, and Counts, Whitehall II. X-axis: Number of standard deviations above or below the mean, y-axis: Hazard ratio for all-cause mortality, shaded areas correspond to 95% confidence intervals. AvAcc: Average acceleration, IG: Intensity Gradient, ENMO: Euclidean Norm Minus One, MAD: Mean Amplitude Deviation, MIMS: Monitor Independent Movement Summary. Models adjusted for sex, season, ethnicity, employment status, smoking, alcohol consumption frequency, and sleep duration. See Supplementary Table S1 for details.

The risk of mortality likewise was lower for higher values of IG from ENMO, with a plateau between 0 and 1 SD, and slightly higher HRs for higher values of IG from ENMO above 1 SD although all CI in this region overlap with 1 (Fig. 1b). The remaining IGs all showed similar patterns with CIs overlapping throughout the range, except for the HR being higher for higher values of IG from Counts between 0 and 1 SD, and no change above 1 SD.

In comparison to AvAcc, observed HRs for IG tended to be higher in the region below the mean, except for Counts where the pattern of the association was similar to AvAcc.

UK Biobank

Mortality risk was lower for higher values of AvAcc from ENMO, with a slight plateau starting just below the mean (Fig. 2a). HRs for AvAcc from MAD, MIMS, and Counts all followed a similar pattern, with CIs overlapping throughout the range. There was greater consistency between measures than observed for Whitehall II.

Hazard ratios for mortality according to (a) AvAcc and (b) IG from ENMO, MAD, MIMS, and Counts, UK Biobank. X-axis: Number of standard deviations above or below the mean, y-axis: Hazard ratio for all-cause mortality, shaded areas correspond to 95% confidence intervals. AvAcc: Average acceleration, IG: Intensity Gradient, ENMO: Euclidean Norm Minus One, MAD: Mean Amplitude Deviation, MIMS: Monitor Independent Movement Summary. Models adjusted for sex, season, ethnicity, employment status, smoking, alcohol consumption frequency, and sleep duration. See Supplementary Table S1 for details.

The HR likewise was lower for higher values of IG from ENMO, again with a slight plateau starting around the mean (Fig. 2b). Again, HRs for IG from MAD, MIMS, and Counts all followed a broadly similar pattern, with overlapping CIs. However, the dose response association was most linear for IG from MIMS with no plateau evident, while the HR for IG from Counts exhibited a local maximum around the mean, and HRs for IG from both Counts and MAD were flat above 1 SD. As was the case for the AvAcc, observed HRs for IG show greater consistency for UK Biobank than for Whitehall II.

Comparing AvAcc to IG, HRs tended to be higher for AvAcc below the mean than for IG below the mean, with HRs for IG decreasing more linearly throughout the range.

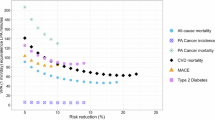

Combined associations of high versus low PA volume and intensity with mortality risk

Whitehall II

With the combination of low AvAcc and low IG as reference, the lowest hazard ratio with ENMO as the measure was for the combination of high AvAcc and high IG (0.65 (0.52, 0.82), Fig. 3). When AvAcc was low, but IG high, risk was also significantly lower (0.69 (0.53, 0.91)). Conversely, there was no significantly lower risk when AvAcc was high, but IG low (0.82 (0.63, 1.05)). The pattern of results was similar for MAD, MIMS, and Counts.

Hazard ratios for mortality according to quadrants of high/low AvAcc and IG. Count of participant per quadrant and hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Low and high correspond to lower and higher values than the median, respectively. Low AvAcc and low IG as reference. *Significantly different from reference at p < 0.05. AvAcc: Average Acceleration, IG: Intensity Gradient, ENMO: Euclidean Norm Minus One, MAD: Mean Amplitude Deviation, MIMS: Monitor Independent Movement Summary, High AvAcc/High IG: high Average Acceleration and high Intensity Gradient, High AvAcc/Low IG: High Average Acceleration and Low Intensity Gradient, Low AvAcc/High IG: Low Average Acceleration and High Intensity Gradient. Models adjusted for sex, season, ethnicity, employment status, smoking, alcohol consumption frequency, and sleep duration. See Supplementary Table S1 for details.

UK Biobank

The lowest risk with ENMO as the measure was again for the combination of high AvAcc and high IG (0.55 (0.51, 0.61)). In contrast to Whitehall II, mortality risk was lower if either AvAcc or IG was high, with the risk difference tending to be greater when AvAcc was high but IG low (0.73 (0.67, 0.81)) than vice versa (0.79 (0.72, 0.86)). The pattern of results was similar to ENMO for MAD and Counts, with risk differences tending to be larger or similar for MAD, but smaller or similar for Counts. For MIMS, the risk was lower for low AvAcc with high IG (0.77 (0.70, 0.85)) than vice versa (0.82 (0.74, 0.90)) akin to the results in Whitehall II.

For both continuous and categorical models, sensitivity analyses including hypothesised mediators as model covariates tended to attenuate the associations but otherwise displayed a similar pattern of results. Excluding participants aged under 60 in UK Biobank did not materially alter results (n cases/total = 56,767/89,848; median (IQR) age at death = 74.5 (70.9, 77.9)). Results are included in Supplementary Figures S4–S8.

Discussion

Risk of all-cause mortality is lower for higher values of either of AvAcc and IG and appears largely similar when AvAcc and IG are derived from ENMO2,5 or when derived from MAD, MIMS, or Counts, with IG adjusted for each of the latter measures23. These findings suggest that, for sufficiently large samples, similar associations between PA and mortality would be obtained, irrespective of whether ENMO, MAD, MIMS or Counts are used as the underlying measure. However, while a difference in the relative impact of AvAcc and IG was evident between cohorts for ENMO, MAD, and Counts, this was not evident for MIMS. Overall, results from the combination of ENMO and MAD, both derived from simpler mathematical formulations, tended to be more consistently similar than from combinations including either of Counts or MIMS, both derived from more complex, layered formulations.

Consistency of combined associations of AvAcc and IG with all-cause mortality across ENMO, MAD, MIMS, and Counts

Irrespective of measure, cohort, or AvAcc, IG was associated with reduced risk of mortality. This indicates that for a given volume of PA, accumulating that volume through higher intensities of PA appear to confer an added benefit. In this aspect, our results are consistent with a 2023 study in Whitehall II indicating that either of AvAcc and IG, derived from ENMO, add predictive value for mortality risk when added to a model including the other27, and to multiple UK Biobank studies investigating associations of AvAcc and IG to mortality risk or incident CVD2,3, or other volume and intensity measures to mortality risk or incident CVD3,4, all using a filtered variant of ENMO, standard in UK Biobank13. A recent analysis in NHANES found similar results, again using ENMO as the measure5. Willems et al. found mixed results for associations of IG with cardiometabolic variables between ENMO, MAD, and Counts using the original bins unadjusted for all measures18. The greater consistency between measures in the present study may partly be ascribed to population, larger sample sizes, and choice of outcome, but also likely indicates improved comparability conferred by using measure-specific adjustments when deriving IG. That consistency may increase with sample size is supported by the fact that results were more consistent in the UK Biobank than in Whitehall II.

That AvAcc appears to be more strongly associated with all-cause mortality in UK Biobank than IG is consistent with the one similar analysis2. In contrast, in Whitehall II, IG was the primary driver for lower mortality risk. In this aspect, our results differ with the Whitehall II analysis mentioned in the prior paragraph, which showed a stronger association for AvAcc than for IG27. Those results were based on data with shorter follow-up period, and consequently, a lower proportion of cases (10.3% vs. 15.1% in the present study). In addition, models included either AvAcc or IG separately and were not mutually adjusted, meaning the findings cannot be directly compared.

The cause for this discrepancy between the Whitehall II and UK Biobank cohorts is unclear. Device differences, including brand and the relatively similar sampling frequencies of 85.7, and 100 Hz for Whitehall II, and UK Biobank, respectively, are unlikely to be a primary cause36, especially in the context of 24-h measures like AvAcc and IG. AvAcc was previously found to be about 10 percent higher at the dominant, compared to the non-dominant, wrist using the GENEActiv and Axivity devices, while IGs were found to be equivalent, with high ICCs for both37, and high shared variances at the epoch level in a separate study38. A slightly higher AvAcc, relative to IG, within UK Biobank, compared to Whitehall II, could potentially be part of the of the reason for the discrepancy. Though, given the high ICCs reported between wrists37 and high shared variance38, the effect is likely to be small. The Whitehall II cohort was older with a correspondingly higher age at death. In an older cohort, higher IG may indicate better general health and functional capacity, through the ability to accumulate PA volume at higher intensities of PA, which would increase the impact of higher IG by proxy. The percentage of respiratory and CVD-related deaths were similar between the Whitehall II and UK Biobank cohorts, though percentage of cancer-related deaths were higher in UK Biobank. Excluding UK Biobank participants under 60 years old at time of accelerometer measurement did not meaningfully change the pattern of results, however, age at death (74.5 (70.9, 77.9)) and percentage of cancer-related deaths (54.3%) were similar to the full cohort. The measured PA levels of the cohorts reflect the age difference, with UK Biobank more active on average than Whitehall II. Considering Schwendinger et al.5, it is unlikely, however, that higher activity levels or age at death could explain the discrepancy, as IG had the strongest association with all-cause mortality in NHANES (2011–2014), as was the case in the present study for Whitehall II, despite the NHANES cohort being more active than either the Whitehall II or UK Biobank cohorts, and showing an age at death similar to UK Biobank5. Schwendinger et al. did not report proportion of cancer-related deaths in NHANES.

Relative agreement of AvAcc and IG derived from ENMO, MAD, MIMS and Counts

Our analyses show the strongest correlations between ENMO and MAD measures for both AvAcc and IG in both cohorts, but slightly weaker correlations for remaining combinations varying between cohorts. The correlations between ENMO and MAD and between MIMS and Counts are very similar between cohorts. This may reflect that ENMO and MAD are both based on the epoch mean of the vector magnitude of acceleration, while MIMS and Counts are in arbitrary units derived from more complex algorithms. The pattern of results, i.e. ENMO and MAD strongly correlated to each other, and less correlated to either of MIMS or Counts, with remaining combinations varying somewhat between datasets, is consistent with other studies18,20,23,38, and the strong correlation between ENMO and MAD, in particular, was expected based on their similarities19.

Strengths and limitations

Notable strengths of this study are the inclusion of both Whitehall II and UK Biobank data, providing important context to the generalisability of results across common differences found between similar cohorts, relating to both cohort characteristics and measurement protocol. UK Biobank in particular is a very large dataset in which multiple analyses examining associations of PA volume and intensity distribution with mortality and other health outcomes provide a rich source of analyses to compare against. Notable limitations include both cohorts being from the UK and being predominantly White, older, relatively healthy, and less socioeconomically deprived25,39. As a result, generalisability of results to diverse geographic, ethnic, and cultural contexts is limited, although this likely impacts PA-mortality associations per se more so than the comparability between measures. Only either wrist was included as wear site, and only one epoch length (5 s) was tested, making generalisability to other wear sites and epoch lengths limited. It is worth noting though, that while epoch length does impact IG, it does not impact AvAcc when based on the measures included herein. Considering Skinner et al.33, shorter epoch durations would likely lead to slightly lower p-values for IG-health associations and potentially slightly stronger effects, while the opposite is true for longer durations. As the present analysis had sufficient power to detect IG-health associations for both cohorts with 5 s epochs, shorter epochs would not be expected to change the results significantly. Longer duration epochs would be expected to make the IG progressively less sensitive. Correlations between AvAcc and IG were also reported to increase with longer epoch durations. Given the mathematical derivation of the IG, this result is expected, meaning that the IG necessitates a relatively short epoch to be valid, and to differentiate meaningfully from AvAcc. This is especially relevant if included in mutually adjusted models with AvAcc as in the present analysis. Differences between cohorts are likely impacted by differences between wrists, device, and sampling rate, though the magnitudes of any such impacts are expected to be small. Of these, the difference between wrists is likely the biggest limitation. Assuming the absolute magnitude of additional non-PA wrist activity reflected in measurement from the dominant wrist is mostly independent of PA levels, it is likely to make up a larger part of measured accelerations in participants with low PA. This could mask differences in PA, potentially leading to some degree of relative underestimation of PA-mortality associations at the lower end of the PA spectrum, when assessed at the dominant wrist, likely more so for AvAcc than for IG. As associations were higher in UK Biobank than Whitehall II, and given the high ICCs between wrists reported by Rowlands et al.37, the effect is likely to be small in general. AvAcc from both ENMO and MAD failed tests of proportionality in the continuous models in the UK Biobank cohort. Schoenfeld residuals showed that the time interaction was negligible for both, and patterns of results remained consistent with the main analysis when including a (slightly positive) time-dependent coefficient for AvAcc (Supplementary Figure S9). Due to the time-dependent coefficient being small (HR: 1.01 (1.01, 1.02) per year, centred on mean age at follow-up or death of 70.3 years for both ENMO and MAD) and proportionality of hazard for AvAcc being met in the remaining six models (all four in Whitehall II, MIMS and Counts in UK Biobank), main results were based on models without the time-dependent coefficient to keep all compared models consistent. It is worth noting, however, that HRs for AvAcc derived from either ENMO or MAD in UK Biobank should be interpreted as averages over time. Some bias due to differences in covariate measurement between the two cohorts, and possible other covariates that were not included, cannot be ruled out. The dichotomisation of high versus low AvAcc or IG is data-driven, meaning that a lack of representativeness in terms of AvAcc and IG would skew the split relative to the underlying population. Further, it discards the resolution provided by continuous data. This limitation is mitigated by presentation and interpretation of models based on the full continuous data alongside the dichotomised models. Using ENMO-based thresholds alone for data trimming leads to potential for some outliers remaining in other measures. With only 15 participants excluded in UK Biobank and none in Whitehall II due to unrealistic ENMO values (> 100 mg), any impact from using ENMO-based thresholds for data trimming would likely be minimal. For the < 0.5th percentile and > 99.5th percentile exclusions there could be more of an impact, however alternative methods each present their own limitations. Applying exclusions for each measure individually would lead to discrete data sets for each analysis, while applying exclusions based on all measures on the same data set would lead to more exclusions. Which option is most valid is debatable. Finally, it is worth noting, that the present analysis was not designed primarily to make inferences about the relative impacts of volume and intensity distribution on mortality risk, but to assess consistency of mortality-risk associations between measures. The ecological validity of such inferences, particular in terms of PA guidelines, exclusively based on mutually adjusted survival models, is limited due to the inherent interconnected nature of volume and intensity distribution of PA, meaning that any recommended added PA will almost inevitably result in changes in both. Comparisons to other studies included here are meant to give context to the applicability of our results, and to serve as an indicator of the face validity of the survival analyses on which they are based. Future studies should further explore the similarities and differences between common epoch summary measures and between other common differences in accelerometer data processing.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that trends of associations of AvAcc and IG with all-cause mortality are likely to be similar between studies utilising ENMO, MAD, MIMS, or Counts as their measure. However, it is important that IG is calculated appropriately for the measure selected by using the proposed adjustments. Our results will enable researchers to have confidence in comparing conclusions from studies that utilise different measures when investigating associations of AvAcc and IG with health. This is highly relevant as all these measures are deployed in large-scale national studies. The main caveats to this are, first, that numerical estimates, and whether results reach statistical significance at a given sample size, may differ somewhat, and second, that results from ENMO and MAD tend to be more consistently similar than from combinations including either of Counts or MIMS. In addition, lack of agreement and comparability in device-based PA measurement methodology has meant that public health guidelines to date have remained reliant primarily on self-report measures40. With all-cause mortality as a critical outcome for PA guideline development41, our results should strengthen the confidence of not only researchers, but also public health officials and policy makers in incorporating device-based measurement, which can enable more accurate and detailed understanding of PA, and in turn more accurate and detailed PA surveillance efforts and PA guidelines.

Data availability

Data, protocols, and other metadata of the Whitehall II study are available to the scientific community via the Whitehall II study data sharing portal (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/psychiatry/research/mental-health-older-people/whitehall-ii/data-sharing). The database supporting the conclusions of this article is available from UK Biobank project site, subject to registration and application process. Further details can be found at https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk. Statistical analysis code is available on GitHub at https://github.com/henrikeckmann.

References

Troiano, R. P. Evolution of public health physical activity applications of accelerometers: A personal perspective. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 6, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmpb.2022-0038 (2023).

Zaccardi, F. et al. Interplay between physical activity volume and intensity with modeled life expectancy in women and men: A prospective cohort analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2024.100970 (2024).

Dempsey, P. C. et al. Physical activity volume, intensity, and incident cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 43, 4789–4800. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac613 (2022).

Strain, T. et al. Wearable-device-measured physical activity and future health risk. Nat. Med. 26, 1385–1391. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1012-3 (2020).

Schwendinger, F. et al. Intensity or volume: The role of physical activity in longevity. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 32, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwae295 (2024).

Rowlands, A. V. Moving forward with accelerometer-assessed physical activity: Two strategies to ensure meaningful, interpretable, and comparable measures. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 30, 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2018-0201 (2018).

Rowlands, A. V. et al. Beyond cut points: Accelerometer metrics that capture the physical activity profile. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 50, 1323–1332. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000001561 (2018).

Dawkins, N. P. et al. Importance of overall activity and intensity of activity for cardiometabolic risk in those with and without a chronic disease. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 54, 1582–1590. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000002939 (2022).

Fairclough, S. J., Taylor, S., Rowlands, A. V., Boddy, L. M. & Noonan, R. J. Average acceleration and intensity gradient of primary school children and associations with indicators of health and well-being. J. Sports Sci. 37, 2159–2167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1624313 (2019).

van Hees, V. T. et al. Separating movement and gravity components in an acceleration signal and implications for the assessment of human daily physical activity. PLoS ONE 8, e61691. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061691 (2013).

Troiano, R. P., McClain, J. J., Brychta, R. J. & Chen, K. Y. Evolution of accelerometer methods for physical activity research. Br. J. Sports Med. 48, 1019–1023. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093546 (2014).

Vähä-Ypyä, H., Vasankari, T., Husu, P., Suni, J. & Sievänen, H. A universal, accurate intensity-based classification of different physical activities using raw data of accelerometer. Clin. Physiol. Functional Imaging. 35, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12127 (2015).

Doherty, A. et al. Large scale population assessment of physical activity using wrist worn accelerometers: The UK Biobank Study. PLoS ONE 12, e0169649. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169649 (2017).

Weber, A. et al. Large-scale assessment of physical activity in a population using high-resolution hip-worn accelerometry: The German National Cohort (NAKO). Sci. Rep. 14, 7927. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58461-5 (2024).

John, D., Tang, Q., Albinali, F. & Intille, S. An open-source monitor-independent movement summary for accelerometer data processing. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2, 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmpb.2018-0068 (2019).

Belcher, B. R. et al. US population-referenced percentiles for wrist-worn accelerometer-derived activity. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 53, 2455–2464. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0000000000002726 (2021).

Neishabouri, A. et al. Quantification of acceleration as activity counts in ActiGraph wearable. Sci. Rep. 12, 11958. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16003-x (2022).

Willems, I. et al. A comparative analysis of 24-hour movement behaviors features using different accelerometer metrics in adults: Implications for guideline compliance and associations with cardiometabolic health. PLoS ONE 19, e0309931. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0309931 (2024).

Brønd, J. C., Møller, N. C. & Grøntved, A. The intrinsic properties of ActiGraph counts and alternatives. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 7, jmpb.2023-0049. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmpb.2023-0049 (2024).

Karas, M. et al. Comparison of accelerometry-based measures of physical activity: Retrospective observational data analysis study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 10, e38077. https://doi.org/10.2196/38077 (2022).

Alexander, C. J., Manske, S. L., Edwards, W. B. & Gabel, L. Adapting the intensity gradient for use with count-based accelerometry data in children and adolescents. Sensors 24 (2024).

Clevenger, K. A., McKee, K. L., Elwood, R., Pfeiffer, K. A. & Montoye, A. H. K. Capturing free-living physical activity: Impacts of data collection and processing decisions on mean acceleration and intensity gradient. Meas. Phys. Education Exercise Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2025.2473904 (2025).

Eckmann, H. R. et al. Adapting the intensity gradient for use across commonly derived accelerometer epoch summary measures: A Learning Network for Advanced Behavioural Data Analysis (LABDA) Project. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmpb.2025-0015 (2025).

Sabia, S. et al. Association between questionnaire- and accelerometer-assessed physical activity: The role of sociodemographic factors. Am. J. Epidemiol. 179, 781–790. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt330 (2014).

Marmot, M. & Brunner, E. Cohort profile: The Whitehall II study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 34, 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh372 (2005).

Sudlow, C. et al. UK biobank: An open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 12, e1001779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 (2015).

Chen, M. et al. Identification of physical activity and sedentary behaviour dimensions that predict mortality risk in older adults: Development of a machine learning model in the Whitehall II accelerometer sub-study and external validation in the CoLaus study. eClinicalMedicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101773 (2023).

LABDA Consortium. Learning Network for Advanced Behavioural Data Analysis, https://labda-project.eu/ (Accessed 18–08 2024)

Marmot, M. G. et al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: The Whitehall II study. Lancet 337, 1387–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k (1991).

Whitehall II Data Dictionary, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/psychiatry/sites/psychiatry/files/w2_data_dictionary_dpuk_v0.51.xlsx (Accessed 18–08 2024)

Migueles, J. H., Rowlands, A. V., Huber, F., Sabia, S. & van Hees, V. T. GGIR: A research community-driven open source R package for generating physical activity and sleep outcomes from multi-day raw accelerometer data. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2, 188–196. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmpb.2018-0063 (2019).

van Hees, V. T. et al. Autocalibration of accelerometer data for free-living physical activity assessment using local gravity and temperature: An evaluation on four continents. J Appl Physiol 1985(117), 738–744. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00421.2014 (2014).

Skinner, A. M. et al. Physical activity volume and intensity distribution in relation to bone, lean and fat mass in children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 33, 267–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.14255 (2023).

Zisou, C. et al. Reproducibility and associated regression dilution bias of accelerometer-derived physical activity and sleep in the UK Biobank. medRxiv, 2025.2001.2016.25320679 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.16.25320679

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 (2016).

Lettink, A., van Wieringen, W. N., Altenburg, T. M., Chinapaw, M. J. M. & van Hees, V. T. Inter-brand, -dynamic range, and -sampling rate comparability of raw accelerometer data as used in physical behavior research. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 7, jmpb.2024-0003. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmpb.2024-0003 (2024).

Rowlands, A. V. et al. Providing a basis for harmonization of accelerometer-assessed physical activity outcomes across epidemiological datasets. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2, 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1123/jmpb.2018-0073 (2019).

Migueles, J. H. et al. Comparability of accelerometer signal aggregation metrics across placements and dominant wrist cut points for the assessment of physical activity in adults. Sci. Rep. 9, 18235. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54267-y (2019).

Fry, A. et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK biobank participants with those of the general population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 186, 1026–1034. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx246 (2017).

Troiano, R. P., Stamatakis, E. & Bull, F. C. How can global physical activity surveillance adapt to evolving physical activity guidelines? Needs, challenges and future directions. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1468–1473. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102621 (2020).

Bull, F. C. et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 54, 1451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the Learning Network for Advanced Behavioural Data Analysis (LABDA). We are grateful to the participants of the UK Biobank and Whitehall II Studies and to those who collected and manage the data. This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. UK Biobank analyses were conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application #89653. This research also used data assets made available by National Safe Haven as part of the Data and Connectivity National Core Study, led by Health Data Research UK in partnership with the Office for National Statistics and funded by UK Research and Innovation (research which commenced between 1st October 2020—31st March 2021 grant ref MC_PC_20029; 1st April 2021—30th September 2022 grant ref MC_PC_20058).

Funding

This is a summary of independent research funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Guarantee funding (EP/X042464/1) for Horizon Europe MSCA Doctoral Networks HORIZON-MSCA-2021-DN-01 (101072993). The LABDA Network has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 101072993. All University of Leicester authors are supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Leicester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). CR is also supported by Applied Research Collaborations – East Midlands (ARC-EM). SS reports fundings from the European Union (ERC grant number 101043884), the Fondation Alzheimer and the Fondation Vaincre Alzheimer. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of UKRI, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, nor the European Commission. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY) to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HE, AR, SS and CR developed the research question and planned the statistical analysis; HE undertook the statistical analysis with guidance from SS and CR, and drafted the manuscript with guidance from AR; SS had access to the Whitehall II data; PCD was Principal Investigator on the UK Biobank Resource Application, and had access to the UK Biobank data along with CR, who prepared the relevant subset of data; IMD and SV helped accessing and processing the Whitehall II data; AR will act as guarantor for this research; All authors contributed to the research design and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

In the Whitehall II study, written, informed consent from participants was obtained at each contact. Research ethics approvals were renewed at each wave; the most recent approval was granted by the National Health Service (NHS) London-Harrow Research Ethics Committee (reference number 85/0938). UK Biobank has full ethical approval from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (16/NW/0274) and all participants gave written informed consent prior to data collection.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eckmann, H.R., Razieh, C., Danilevicz, I.M. et al. Impact of accelerometer epoch summary measure on associations between physical activity and all-cause mortality in Whitehall II and UK Biobank. Sci Rep 16, 761 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30237-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30237-5