Abstract

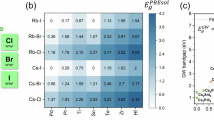

Fabrication of ultrathin (sub-2 nm) oxide semiconductor memristors poses the fundamental challenge of achieving oxide growth with atomic precision in terms of electronic structure and defect formation. Recently, ultrathin memristors consisting of bilayers of mixed \(\textrm{Al}_2\) \(\textrm{O}_3\) and MgO atomic layers were fabricated using an in vacuo atomic layer deposition process. This approach offers a unique platform for precise atomic control of oxygen vacancies in the device in which the vacancies are introduced by placing MgO atomic layers between pristine \(\textrm{Al}_2\) \(\textrm{O}_3\) layers. In this work, we present a systematic operando Hard X-ray PhotoElectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES) study of the switching of such memristors, combined with complementary current-voltage and capacitance-voltage (C-V) measurements. We used a memristor stack of \(\textrm{Al}_2\) \(\textrm{O}_3\)/MgO atomic layers, with the MgO-containing oxide deposited on the bottom Al metal electrode and a pure \(\textrm{Al}_2\) \(\textrm{O}_3\) layer below the top Pd electrode. HAXPES analysis shows a substantial change in the chemical shift of the Aluminum oxide when switching between the ”OFF” and ”ON” states indicative of a redistribution of oxygen vacancies in the device active layer. Interestingly, subsequent switching to the OFF state shows hysteretic behavior indicating the retention of some oxygen vacancies in the top \(\textrm{Al}_2\) \(\textrm{O}_3\) layer. This vacancy retention can be correlated with the stochastic behavior of the switching voltage observed in these devices. C–V measurements show a clear frequency-dependent response in the OFF state, consistent with enhanced polarization and vacancy trapping at low frequencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Memristors are two-terminal devices that behave like nonlinear resistors with memory, exhibiting a pinched hysteresis loop in their current–voltage (I-V) response1,2; this behavior allows memristors to serve as artificial synapses for neuromorphic computing3. Since the pioneering work by Williams4 who developed a Pt/Ti\(\textrm{O}_2\)/TiO\(_x\)/Ti memristor, metal-oxide-metal memristors have shown remarkable improvements in both performance and stability across diverse material platforms. Notably, device endurance measured by open-loop switching cycles has exceeded \(\textrm{10}^{12}\) cycles, and switching times under 2 ns have been demonstrated; positioning memristors as strong candidates for use in high-speed, high-reliability applications4. These performance gains have been underpinned by developing an understanding of the underlying physical mechanisms. In most metal-oxide-metal systems, resistive switching is now broadly attributed to the field-driven drift and diffusion of mobile ionic species, particularly oxygen vacancies (VO), in combination with localized electrochemical oxidation/reduction (redox) reactions at active interfaces5,6,7,8,9,10,11. These processes dynamically modulate the local conductivity of the oxide, forming and rupturing conductive filaments or changing barrier profiles, depending on the specific switching mode (filamentary or interfacial).

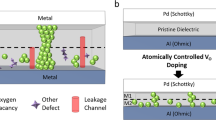

The need to integrate memristors with complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technologies requires development of oxides with length scales comparable to current state-of-art CMOS processes, i.e. a few nm. This in turn requires the development of oxides with precise control of vacancies at these length scales. One metal-oxide-metal memristor structure that addresses some of the associated problems of ultra-thin oxides is the ”O1/O2” bilayer structure12, consisting of a stoichiometric oxide layer (O1) and a defective oxide layer (O2) which acts as a reservoir of VO. Under electrical bias, VO diffuse from the O2 layer into the O1 layer forming conductive filaments between the two metal electrodes. These conductive filaments lead to a reproducible switching between a high resistance ”OFF” state and a low resistance ”ON” state at SET and RESET biases. The use of such a bilayer oxide facilitates the precise control of vacancies, even in ultra-thin films, and enables high ON/OFF resistance ratios.

While the presence of VO is a necessary condition for memristive switching, uncontrolled or parasitic defects, especially those located at the oxide/electrode interfaces, can severely impact device performance. These interfacial defects often act as leakage pathways or charge trapping centers, contributing to increased off-state currents, reduced endurance, poor retention, and stochastic switching behavior13,14,15. Achieving atomic-level control over defect formation, particularly at buried interfaces, remains a critical challenge in the scalable fabrication of reliable and uniform memristors. To address these issues, recent innovations in in vacuo atomic layer deposition (ALD), wherein the metal deposition and ALD processes are performed without intervening exposure to atmosphere, have provided promising routes to engineer oxide layers with minimal contamination and well-defined interfaces16,17. Goul et al.12, for example, utilized in vacuo ALD to dope Al\(_2\)O\(_3\) films with atomic layers of MgO as a source of VO, allowing for the controlled incorporation of VO according to the number and location of MgO layers. This selective doping strategy not only enhanced the resistivity of the dielectric matrix but also increased the concentration and distribution controls of VO, both critical parameters in memristive switching18,19. The resulting Al\(_2\)O\(_3\)/MgO atomic layer stacks enabled highly tunable switching characteristics, with ON/OFF resistance ratios ranging from 10 to 40,000 depending on the thickness and stacking order, demonstrating that atomic-scale material engineering can directly influence the macroscopic behavior of these devices.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) has been extensively employed to study oxidation states in memristive devices20,21,22. In most cases, however, XPS has been limited to ex-situ measurements, where the resistive switching process occurs outside the measurement environment. As a result, the insights obtained are often static and do not fully capture the dynamic changes in chemical states during device operation. Furthermore, the inherently surface-sensitive nature of XPS makes it difficult to probe buried interfaces or active layers, particularly in devices with traditional metal–oxide–metal architectures where the functional oxide layer is sandwiched between electrodes. To overcome this limitation, Köymen et al.23 demonstrated operando XPS measurements by replacing the conventional top metal electrode with a single-layer graphene sheet. Owing to its high electrical conductivity and optical transparency, graphene served as an effective top electrode while allowing photoexcited electrons from the underlying oxide layer to be detected. This approach can potentially enable real-time monitoring of the chemical environment within the active layer under applied bias. However, while the use of graphene facilitates in-situ characterization, it deviates significantly from the architecture of practical memristive devices, which typically rely on metal contacts to control and confine electric fields. Moreover, the work function difference between graphene and conventional metal electrodes can influence electrochemical potential distributions and thereby alter the dynamics of VO migration and charge transport.

In this work, we use Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES) and capacitance–voltage (C–V) measurements to investigate the electronic structure and switching behavior of doped Al\(_2\)O\(_3\)-based bilayer memristors during operando SET and RESET cycles. C–V measurements were used to probe the frequency-dependent electrical response of the device, revealing trends in polarization, charge trapping, and switching thresholds. To complement these electrical insights with direct chemical analysis, we utilized HAXPES to monitor changes in the chemical environment and electronic structure of the buried oxide layers and interfaces under applied bias. HAXPES provides a powerful tool for probing the chemical and electronic structure of buried layers and interfaces24. Unlike conventional XPS, which is limited to a surface-sensitive depth of up to few nm, HAXPES can access depths up to 30 nm, enabling direct, non-destructive analysis of functional layers within fully processed stacks25,26. This makes it especially valuable for studying oxide-based memristors, where switching often occurs at or near the metal/oxide interface regions typically inaccessible by XPS. Importantly, HAXPES maintains the core advantages of XPS, including elemental specificity and sensitivity to chemical state, but with significantly reduced sensitivity to surface contamination and artifacts. Its compatibility with operationally relevant structures allows for more realistic insights into charge transport, defect dynamics, and redox behavior in working devices.

Results and discussions

The initial characterization of the memristors focused on transport measurements, specifically I–V and C-V analysis. Figure 1 shows the I–V characteristics of one memristor device measured both prior to and following the HAXPES measurements. I-V characteristics for other devices were broadly similar, though the specific SET and RESET biases varied with the device size and metal thickness. Clear bipolar resistive switching behavior was observed, with the SET transition occurring at just above +0.5 V and the RESET transition slightly below –1.8 V.

Figure 2 shows the C-V characteristics measured over a complete SET/RESET cycle at different frequencies. Prior to each cycle, the memristor was reset to the same ”initial” state by applying conditioning voltages beyond its RESET threshold (approximately -3.3 V) and ensuring its resistance in the OFF state at 0.1 V was within the range of 80 k\(\Omega\) to 100 k\(\Omega\). A consistent reduction in capacitance is observed between the OFF and ON states across all frequencies, which is attributed to the lateral expansion of the conductive filament spanning the device thickness during switching. Pronounced hysteresis is observed in the C-V curves, with a clear increase in the voltage loop size as the frequency decreases. This behavior can be interpreted from two complementary perspectives. First, the C-V loop expansion may arise from frequency-dependent temporal response in polarization mechanism. This is further evident by the strong frequency dependence of the capacitance in the OFF state, where a clear reduction is observed with increasing frequency. Such dispersion is commonly associated with the suppression of slow polarization mechanism in the dielectric, like charge trapping, interface charging, and ion migration, which are unable to follow fast AC signals and are effectively ”frozen” at higher frequencies. At lower frequencies, however, these mechanisms can respond more effectively, leading to an enhanced net polarization and corresponding increase in the measured capacitance27.

The higher polarization observed at lower frequencies is also reflected in the steeper slopes of the C-V curves, and it influences the switching dynamics. Notably the SET voltage, although consistent with the value shown in the I–V curve, increases as the measurement frequency decreases. This observation can be explained by the fact that the increased internal polarization reduces the effective electric field across the device, requiring a higher applied bias to drive oxygen vacancies from the bottom reservoir to the top electrode and initiate filament formation. A similar trend is also observed in the ON state, where the RESET voltage also increases at lower frequencies. In this state, the presence of a conductive filament causes the memristor to behave like a normal resistor, with its capacitance having a slight increase with frequency. This effect is likely due to the differences in the lateral extent of the filament: broader at low frequencies and narrower at high frequencies, potentially explaining the observed increase in RESET voltage at low frequencies.

In addition to these dielectric effects, the observed enlargement of the C–V hysteresis loops at lower frequencies may also indicate an enhanced field-driven oxygen vacancy migration. At lower frequencies, the longer period of the AC signal allows oxygen vacancies to respond more effectively to the applied field, promoting more extensive migration and dynamically altering the local oxygen vacancy distribution within the oxide during each voltage sweep. This enhanced ionic activity produces larger capacitance changes and a wider hysteresis loop. Conversely, at higher frequencies, the limited response time of vacancy migration and other slow polarization mechanisms constrains their contribution, resulting in narrower loops.

While electrical characterization of the memristors provides valuable insights into frequency-dependent polarization dynamics and switching behavior, it primarily probes the macroscopic electrical response of the device. To directly investigate the underlying chemical and structural changes responsible for these electrical characteristics, particularly the redistribution of oxygen vacancies across different switching states, we employed operando HAXPES. To confirm the memristor device behavior under HAXPES conditions (ultrahigh vacuum and X-ray illumination), we will first turn to the Pd 3d core line data measured at 3500 eV photon energy. A different device with a thinner Pd layer was used for this measurement, and its I–V curve is shown in the inset of Fig. 3. In-vacuum electrical measurements conducted during the HAXPES acquisition (data not shown) further verified that the device remained electrically active and continued to switch reliably under HAXPES measurement conditions. For the operando HAXPES measurements, the Pd electrode was connected to the ”Low” connection of the electrometer and connected to ground common with the analyzer, while the Al side was biased via the ”High” side of the electrometer. Figure 3 shows the relative shift in the Pd 3d\(_{5/2}\) core line referenced to the Al 1s core line under different bias conditions. In the OFF state, the slope of the binding energy shift with respect to applied voltage is close to 1, indicating that nearly the entire voltage drop is across the oxide layer. This behavior is consistent with a capacitive or insulating regime, where minimal current flows and the applied bias appears almost entirely across the dielectric. In contrast, when the device switches to the ON state, the slope decreases to less than 1, indicating that only a fraction of the applied voltage is dropped across the oxide. This reduced shift reflects the fact that the bias drop is now shared across the entire circuit due to the enhanced current through the oxide layer, consistent with the formation of a conductive filament or percolation path within the oxide. In this state, the device behaves more resistively. This trend aligns with simple equivalent circuit models for memristive systems, where the device can be modeled as a voltage divider consisting of a variable resistor (memristive channel) and fixed contact or series resistances28. In the OFF state, oxide resistance dominates the circuit, leading to a full voltage drop across the active region. In the ON state, the internal resistance decreases, and the voltage drop is shared between the filament and other circuit elements. The observed binding energy shifts in the Pd core level thus provide a direct spectroscopic probe of the internal potential distribution and support the filamentary switching mechanism commonly associated with memristors.

(Left) Schematic illustration of the HAXPES measurement setup and probed sample. (Right) Relative shift of the Pd 3d\(_{5/2}\) core line as a function of applied bias. The ”ON” state is plotted in blue and the ”OFF” state in red. Error bars represent the expected uncertainty in peak position (see text). The inset shows multiple I-V sweeps across the device prior to HAXPES measurement. Numbered points indicate specific bias positions, which correspond to the locations marked on the I–V sweeps shown in the inset.

Figure 4 shows the corresponding Al 1s core-level spectra collected at a photon energy of 3500 eV under various applied bias conditions; to account for the shifting of the peak with applied bias, here the kinetic energy scale is aligned to the center of the sharper, metallic Al peak from the bottom electrode. The broader feature, shifted approximately -3 eV in kinetic energy from the metal peak, arises from the active oxide. In XPS, such chemical shifts reflect changes in the local chemical environment, including oxidation state, bonding, and the electronegativity of surrounding atoms29. Tracking the oxide position from Fig. 4, we first note a chemical shift of \(-3.1\) eV for the oxide in the initial 0 V OFF state. With a 1 V applied bias, the oxide shift decreases to \(-2.8\) eV. Here it is important to note that in the presence of an applied bias, the peak position will reflect not only chemical changes but also electrostatic effects. The oxide peak has shifted with the (biased) Al metal but not completely, reflecting the potential drop across the oxide layer. Increasing the applied bias to the SET condition at +2.5 V, the oxide shift further decreases to -2.7 eV. As discussed above, once the device has switched to the ON state, the oxide is no longer able to sustain the full potential drop; thus by electrostatic arguments alone, the oxide shift would be expected to increase as the potential drop across the oxide has decreased. The fact that the oxide shift actually decreases reflects the migration of oxygen vacancies towards the surface of the sample which provides a chemical shift in addition to the electrostatic shift. Decreasing the applied bias between +1 V and -1 V in the ON state, the oxide shift remains near -2.5 eV with only minor changes, again reflecting the electrostatic shifts from the (reduced) bias drop across the oxide. When the RESET voltage of -3.3 V is reached, the oxide shift increases slightly to -2.6 eV. At this bias the device has been returned to the OFF state, and the full potential drop is again sustained within the oxide. Intriguingly, when the bias is returned to 0 V after the RESET transition, the chemical shift does not return to its original value, indicating a residual change in the local chemical environment possibly due to incomplete reversal of VO distribution. These residual changes have important implications for device behavior. Over successive voltage cycling, such irreversible or slowly evolving modifications can lead to drift in switching voltage and variations in ON/OFF resistance ratios, explaining the stochastic changes in switching voltages frequently observed during endurance tests or cycling experiments30,31.

Al 1s core line at 3500 eV photon energy for different applied bias. The metal line indicated in the spectrum is from the Al bottom electrode. The red line is the OFF state and the blue line the ON state. The sample was preconditioned by I–V cycling to achieve reproducible SET/RESET behavior prior to HAXPES measurements; it was not in the pristine, pre-forming state.

To further disentangle the effects of electrostatic shifts from genuine chemical changes and to probe the depth distribution of VO, we collected Al 1s core-level spectra at 0 V applied bias in both the ON and OFF states using multiple photon energies. Figure 5 presents the Al 1s spectra acquired at photon energies of 3000 eV, 4000 eV, 5000 eV, and 6000 eV, with all spectra collected from a single SET/RESET cycle. As the photon energy increases, the relative contribution of deeper layers increases. The inelastic mean free path for an Al 1s photoelectron in an Al\(_2\)O\(_3\) film is estimated to be 2.6 nm at 3000 eV photon energy, 3.9 nm at 4000 eV, 5.1 nm at 5000 eV, and 6.3 nm at 6000 eV, respecitvely, as calculated per Jablonski et al.32 All spectra were referenced to the Al 1s peak from the metallic bottom electrode to ensure a consistent energy calibration across measurements. At 3000 eV, which primarily probes the upper portion of the oxide layer and the region near the top Pd electrode, we observe a slight reduction in chemical shift in the ON state compared to the OFF state. This is consistent with the formation of conductive filaments: the migration of VO toward the top electrode lowers the local oxidation state, shifting the Al 1s peak to lower binding energy. This behavior provides spectroscopic evidence of filament formation localized near the top interface, in agreement with common models of memristor switching.

In contrast, at all higher photon energies, where the probing depth extends further into the bulk and toward the bottom interface, the chemical shift from the metallic Al peak in the ON state increases relative to the OFF state. This apparent reversal in peak position is consistent with depletion of VO near the bottom region during the SET process, resulting in a higher local oxidation state and correspondingly a peak shift to higher binding energy. These depth-dependent chemical shifts provide direct spectroscopic evidence for the vertical redistribution of VO, supporting a filamentary switching mechanism that is highly localized and asymmetric across the oxide layer. This depth-resolved analysis thus confirms that resistive switching is accompanied by spatially non-uniform redox changes, with vacancy accumulation near the top interface and depletion near the bottom. Such spectroscopic signatures of vacancy migration provide a powerful tool for linking the electronic behavior of memristive devices to underlying atomic-scale structural and chemical changes.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated the application of operando HAXPES as a non-destructive, depth-sensitive probe to investigate resistive switching mechanisms in doped Al\(_2\)O\(_3\)-based memristors. By applying external bias during measurement and varying the incident photon energy, we achieved spectroscopic access to both the top and bottom interfaces of the device, allowing us to spatially resolve the electronic and chemical changes associated with device operation. By leveraging the depth sensitivity of HAXPES at multiple photon energies, we tracked the Al 1s core-level shifts under 0 V bias and across switching states. These measurements enabled us to further disentangle electrostatic potential shifts from genuine chemical shifts associated with VO redistribution. We observed spectroscopic signatures of filament formation during the SET transition, including a reduction in the oxide chemical shift near the top electrode and a corresponding increase near the bottom electrode. These trends provide direct evidence of vertical VO migration, supporting a localized filamentary switching mechanism. Importantly, the chemical environment did not fully recover upon returning the device to zero bias after RESET, highlighting the presence of residual structural or chemical changes. These irreversible or metastable states are likely contributors to the stochastic variation in switching voltages observed during repeated cycling.

In parallel to the spectroscopic analysis provided by HAXPES, C-V measurements were employed to probe the macroscopic electrical behavior and dynamics of the memristor. These measurements complement the spectroscopic insights by revealing the influence of vacancy redistribution on its capacitive properties. A significant drop in capacitance was observed between the OFF and ON states, reflecting the underlying changes in the filamentary conduction and vacancy migration. Moreover, the pronounced hysteresis observed in the C-V curves, particularly at low frequencies, provides further evidence of the role of slow dynamic processes, such as charge trapping, interface charging, and ionic migration, in governing the switching behavior. The strong frequency dependence in the OFF state suggests that these processes dominate at low frequencies and are mitigated in the ON state, where the conductive filament governs the device dynamics.

Methods

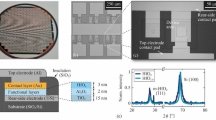

Ultrathin memristors with O1/O2 bilayer structures composed of ALD-Al\(_2\)O\(_3\)/ALD-MgAlO\(_x\) were fabricated using in vacuo ALD. To tune the electronic structure and VO concentrations in the O1 and O2 layers, a controlled number of ALD-grown MgO atomic layers were inserted within the Al\(_2\)O\(_3\) matrix. The thickness of the O1/O2 layers were precisely controlled at the atomic level by adjusting the number of ALD cycles, as each cycle generates one atomic layer of either Al\(_2\)O\(_3\) or MgO, with thickness between 0.10 nm and 0.11 nm, as confirmed from high resolution transmission electron microscopy12. The total thicknesses of the Al\(_2\)O\(_3\)/MgO memristors of 17 atomic layers (14 Al\(_2\)O\(_3\) and 3 MgO) is around 1.8-1.9 nm. Memristors were patterned using a shadow mask, allowing 12 devices to be fabricated per chip with three different active areas, 200 µm \(\times\) 200 µm, 200 µm \(\times\) 300 µm, and 200 µm \(\times\) 400 µm, to assess device uniformity. Top and bottom electrodes (Pd and Al, respectively) were deposited via DC magnetron sputtering in an integrated in vacuo ALD system, with a base pressure below \(7\times 10^{-5}\) Pa. 10 nm thick Al was sputtered using an Ar plasma at 1.9 Pa, and 90 W (deposition rate approximately 0.5 nm/s), while 20 nm Pd was deposited at 3.9 Pa and 45 W (approximately 1 nm/s), with a target-to-substrate distance of approximately 6 cm. The Si/SiO\(_2\) (500 nm) substrate was transferred from the load-lock to the sputtering chamber via a transfer rod to enable Al bottom electrode deposition without ambient exposure. For HAXPES measurements the thickness of the top Pd electrode was limited to 20 nm. The devices were mounted on a custom carrier board and wire bonded to readout pads. Wires were silver epoxied to the readout pads and were connected to an external commercial electrometer via a vacuum electrical feed through. Prior to the measurements, the devices were cycled through SET/RESET cycles to confirm functionality.

Operando HAXPES measurements were performed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology ”Spectroscopy Soft and Tender II” beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source II, Brookhaven National Laboratory33. Energy selection was performed using a double-crystal monochromator. The hemispherical electron analyzer is mounted with the acceptance cone oriented parallel to the electric polarization vector of the incident X-ray beam and perpendicular to the beam propagation direction. All data were collected with photon energy between 3000 eV and 6000 eV. HAXPES measurements were performed on a \(200\,\mu m\times 400\,\mu m\) device. Uncertainty in the HAXPES peak positions is expected to be less than 0.05 eV as determined from repeated measurements of Au and Ag reference standards.

To ensure the majority of the photoelectron signal originated from the actual device under probe, careful sample alignment was performed by placing the analyzer in ”Transmission” mode and aligning the X-ray beam to the position where photoelectron signal from the Pd top contact was maximized. The incident focused X-ray beam size (approximately 50 µm vertical \(\times\) 350 µm horizontal) was further slit down to 100 µm in the horizontal dimension to ensure X-ray illumination is primarily in the active area of the device. The samples subjected to HAXPES analysis were preconditioned through electrical cycling and were therefore not in their pristine, pre-forming state. Controlled I–V loops were conducted beforehand to ensure reproducible SET/RESET transitions during the operando measurements. I–V and C–V measurements were performed using a commercial source meter and a semiconductor parameter analyzer, respectively, both operated with a voltage sweeping rate of approximately 2 mV \(s^{-1}\). The accuracy and resolution of the instruments were 0.012 % and 1 aF, respectively.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request by contacting the corresponding author at rumaiz@bnl.gov.

References

Chua, L. Memristor-the missing circuit element. IEEE Trans. Circuit Theory 18, 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCT.1971.1083337 (1971).

Chua, L. If it’s pinched it’s a memristor. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 29, 104001. https://doi.org/10.1088/0268-1242/29/10/104001 (2014).

Li, C. et al. Efficient and self-adaptive in-situ learning in multilayer memristor neural networks. Nat. Commun. 9, 2385. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04484-2 (2018).

Yang, J. J. et al. Memristive switching mechanism for metal/oxide/metal nanodevices. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 429–433. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2008.160 (2008).

Kwon, D.-H. et al. Atomic structure of conducting nanofilaments in tio2 resistive switching memory. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2009.456 (2010).

Yang, J. J. et al. Dopant control by atomic layer deposition in oxide films for memristive switches. Chem. Mater. 23, 123–125. https://doi.org/10.1021/cm1020959 (2011).

Yang, J. J. et al. Metal/tio2 interfaces for memristive switches. Appl. Phys. A 102, 785–789. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-011-6265-8 (2011).

Torrezan, A. C., Strachan, J. P., Medeiros-Ribeiro, G. & Williams, R. S. Sub-nanosecond switching of a tantalum oxide memristor. Nanotechnology 22, 485203. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/22/48/485203 (2011).

Yang, J. J. et al. High switching endurance in taox memristive devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 232102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3524521 (2010).

Dodson, B. et al. Atomic-scale oxygen-vacancy engineering in sub-2 nm thin al2o3/mgo memristors. Nano Express 5, 025001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2632-959X/ad34a5 (2024).

Yang, J. J., Strukov, D. B. & Stewart, D. R. Memristive devices for computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2012.240 (2013).

Goul, R. et al. Atomic-scale tuning of ultrathin memristors. Commun. Phys. 5, 260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-022-01037-4 (2022).

Huang, X.-D. et al. Forming-free, fast, uniform, and high endurance resistive switching from cryogenic to high temperatures in w/alox/al2o3/pt bilayer memristor. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 41, 549–552. https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2020.2977397 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Highly uniform, self-compliance, and forming-free ald \(\text{ HfO}_{2}\) -based rram with ge doping. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 59, 1203–1208. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2012.2182770 (2012).

Vishwanath, S. K., Woo, H. & Jeon, S. Enhancement of resistive switching properties in al2o3 bilayer-based atomic switches: multilevel resistive switching. Nanotechnology 29, 235202. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6528/aab6a3 (2018).

Wu, J. Z., Acharya, J. & Goul, R. In vacuo atomic layer deposition and electron tunneling characterization of ultrathin dielectric films for metal/insulator/metal tunnel junctions. Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology A 38, 040802, https://doi.org/10.1116/1.5141078 (2020). https://pubs.aip.org/avs/jva/article-pdf/doi/10.1116/1.5141078/16009848/040802_1_online.pdf.

Acharya, J., Wilt, J., Liu, B. & Wu, J. Probing the dielectric properties of ultrathin al/al2o3/al trilayers fabricated using in situ sputtering and atomic layer deposition. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 10, 3112–3120. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b16506 (2018). PMID: 29293311.

Liu, M. et al. Experimental studies on the conduction mechanism and electrical properties of the inverted ba doped zno nanoparticles based memristor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 073505, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5110888 (2019). https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.5110888/14040623/073505_1_online.pdf.

Singh, R. et al. Highly transparent solid-state artificial synapse based on oxide memristor. Appl. Surf. Sci. 536, 147738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147738 (2021).

Kindsmüller, A. et al. Valence change detection in memristive oxide based heterostructure cells by hard x-ray photoelectron emission spectroscopy. APL Materials 6, 046106, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5026063 (2018). https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apm/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.5026063/14560389/046106_1_online.pdf.

Bousoulas, P., Giannopoulos, I., Asenov, P., Karageorgiou, I. & Tsoukalas, D. Investigating the origins of high multilevel resistive switching in forming free ti/tio2-x-based memory devices through experiments and simulations. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 094501, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4977063 (2017). https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jap/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.4977063/19773578/094501_1_online.pdf.

Li, C. et al. Observation of oxygen vacancy migration in memory devices based on zno nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 144503, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4979973 (2017). https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jap/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/1.4979973/15193175/144503_1_online.pdf.

Köymen, I., Aydoğan Göktürk, P., Kocabaş, C. & Suzer, S. Chemically addressed switching measurements in graphene electrode memristive devices using in situ xps. Faraday Discuss. 213, 231–244, https://doi.org/10.1039/C8FD00129D (2019).

Rumaiz, A. K. et al. Interface formation and schottky barrier height for y, nb, au, and pt on ge as determined by hard x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. AIP Advances 13, 015305, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0101688 (2023). https://pubs.aip.org/aip/adv/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0101688/16699610/015305_1_online.pdf.

Weiland, C., Rumaiz, A. K. & Woicik, J. C. HAXPES Measurements of Heterojunction Vol. Alignment, 381–405 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016).

Woicik, J. Hard X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (HAXPES) (Springer Series in Surface Sciences. Springer International Publishing, Berlin, 2015).

Kingery, W. D., Bowen, H. K. & Uhlmann, D. R. Introduction to ceramics (John wiley & sons, 1976).

Ielmini, D. & Waser, R. (eds) Resistive switching (Wiley-VCH Verlag, Weinheim, Germany, 2016).

Seah. D. Briggs, M. S. (ed.) Practical Surface Analysis Volume 1 Auger and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (Wiley-VCH Verlag, Chichester UK, 1990).

Guan, X., Yu, S. & Wong, H.-S.P. On the switching parameter variation of metal-oxide rram-part i: Physical modeling and simulation methodology. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 59, 1172–1182. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2012.2184545 (2012).

Ambrogio, S. et al. Understanding switching variability and random telegraph noise in resistive ram. In 2013 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting, 31.5.1–31.5.4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2013.6724732 (2013).

Jablonski, A., Tanuma, S. & Powell, C. J. Calculations of electron inelastic mean free paths (imfps). xiv. calculated imfps for lif and si3n4 and development of an improved predictive imfp formula. Surf. Interface Anal. 55, 609–637 (2023).

Weiland, C. et al. Nist haxpes at nsls and nsls-ii. Synchrotron Radiation News 31, 23–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/08940886.2018.1483654 (2018).

Funding

This research used resources of the National Synchrotron Light Source-II, which are U.S. DOE Office of Science Facilities, at Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. JZW, RG and AM acknowledge National Science Foundation under contracts of NSF-EECS-2314401 and NSF-DMR-2425549.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AKR and CW conceived the experiment(s), FC, AKR, CW, and IH did the HAXPES measurements, FC, AKR, AO, MB, AJK, SK, and SM conducted the transport measurements, RG, AM, and JZW fabricated the samples, FC, AKR, CW, JCW, DPS, JZW, and GAC analyzed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Capocasa, F., Rumaiz, A.K., Weiland, C. et al. Tracking oxygen vacancy migration in memristor devices using operando hard X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Sci Rep 16, 755 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30246-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30246-4