Abstract

Environmental contamination by carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria (CR-GNB) contributes to healthcare-associated infections in intensive care unit (ICU). However, contamination in areas away from isolated patients remains inadequately characterized, and local epidemiological data are limited. A comprehensive surveillance study was conducted in the ICU of a tertiary hospital from January 2019 to December 2022. Monthly collections included clinical specimens (sputum, urine, blood) and environmental samples (inanimate surfaces, healthcare workers’ hands). Gram-negative bacteria were cultured, and carbapenem sensitivity testing was performed. Among 5,097 clinical specimens collected over the 4-year study period, 898 (17.6%) GNB isolates and 405 (8.0%) CR-GNB isolates were detected, with Klebsiella pneumoniae and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) being the most common species. From 2,215 environmental samples, 144 (6.5%) GNB and 90 (4.1%) CR-GNB strains were identified, predominantly A. baumannii and CRAB. The overall CR-GNB environmental contamination rates were highest on work coats (6.8%), followed by nonisolated patient medical devices (5.8%), nonisolated patient bed units (4.3%), mobile phones (4.1%), doctors’ offices and nurses’ stations (3.6%), and healthcare workers’ hands (2.0%). Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between the monthly number of positive A. baumannii or CRAB isolates from environmental samples and clinical specimens. CR-GNB, particularly CRAB, contaminates ICU environments, including nonisolated patient areas and healthcare stations, highlighting the need for enhanced environmental surveillance in the ICU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The gram-negative bacteria (GNB) Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) are among the “ESKAPE pathogens” that pose a great threat to antibiotic use and resistance in healthcare institutions. Carbapenems are key last-resort antimicrobial agents in the clinical field, as they are considered the treatment for multidrug-resistant (MDR) GNB infections1. With the increasing use of carbapenems, carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria (CR-GNB) have become a major concern in healthcare-associated infections (HAIs)2. The prevalence of CR-GNB has increased since 2005, particularly among patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU)3. The high overall mortality rate (between 20% and 71%) among patients infected with CR-GNB poses a serious threat to clinicians4.

Nosocomial environmental contamination plays an important role in the transmission of HAIs5,6. It is estimated that 20% of HAIs originate from contaminated environmental surfaces7. The hospital environment acts as a significant reservoir for pathogens such as CR-GNB. Several pathogens (e.g., A. baumannii) can persist in the environment for extended periods, and molecular studies have confirmed homology between environmental and clinical isolates8,9. In recent years, transmissions caused by GNB, especially CR-GNB, have been observed in hospitals worldwide; these infections cause substantial public health problems and pose serious challenges to infection control10,11.

Currently, regular surveillance of nosocomial CR-GNB environmental contamination is inadequate, except for during outbreaks or suspected outbreaks of HAIs caused by CR-GNB for epidemiological investigations. In addition, most studies12,13 on nosocomial environmental contamination have focused on the environment of CR-GNB carriers, who are categorized as isolated patients and require contact precautions, but few studies have reported on environmental contamination away from isolated patients. Therefore, we conducted environmental and clinical surveillance of CR-GNB in the ICU over a 4-year period to assess the rate of environmental contamination of GNB and CR-GNB strains in the environment away from isolated patients as well as to determine the proportion of GNB and CR-GNB strains to provide information for infection prevention and control (IPC) and appropriate interventions in the ICU.

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted from January 2019 to December 2022 in the intensive care unit of a 1200-bed tertiary teaching hospital in China. The ICU had 10 rooms with 21 beds until August 2022, when it was expanded to 15 rooms with 31 beds.

IPC measures

To stop the spread of CR-GNB (CRKP, CRAB, or CRPA) in the hospital, patients with CR-GNB detected on admission or during hospitalization are categorized as isolated patients and require contact precautions. Contact precautions should include single-room isolation or patient cohorting. Conversely, nonisolated patients are those who tested negative for CR-GNB at admission and throughout their hospitalization.

Environmental services staff perform routine and terminal cleaning and disinfection in ICU. Bed units, medical devices, doctors’ offices and nurses’ stations should be cleaned and disinfected with 500 mg/L chlorine-containing disinfectant (Hunan Zhongda Zhongya Medical Technology Co., Ltd.) twice daily. The protocol of routine cleaning and disinfection begins with doctors’ offices and nurses’ stations, followed by bed units and medical devices for non-isolated patients, and finally bed units and medical devices for isolated patients. We provide pre-service training for environmental services staff in routine and terminal disinfection of environmental surfaces in the ICU, as well as 1–2 training per year. The Infection Control Center employs the Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Bioluminescence Monitoring System (Hygiena, USA) quarterly to verify environmental cleaning and disinfection efficacy. The established pass thresholds are: post-disinfection monitoring < 100 relative light units (RLU), and during-use monitoring < 300 RLU.

The ICU has implemented a rigorous prospective hand hygiene monitoring programme. Under this scheme, trained infection control nurses observe approximately 60 hand hygiene opportunities per month across the entire ICU, utilising the World Health Organisation’s “Five Key Moments for Hand Hygiene” framework. Hand hygiene compliance rates are calculated as the percentage of observed opportunities where the procedure was actually performed.

Clinical specimens and isolates

Routine clinical specimens, including sputum, urine, and blood, were collected for diagnostic purposes from patients admitted to the ICU between 2019 and 2022. K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa strains were isolated from clinical specimens using standard microbiology laboratory procedures and identified and tested for drug susceptibility on a fully automated Vitek 2 COMPACT microbiology system (BioMerieux, Craponne, France). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100 performance standards (2019–2022 editions). Duplicate strains were defined as the same bacterial species from the same specimen source from the same patient, and only the first strain of the duplicate strains was included in the analysis. The quality control strains used were the standard strains purchased from the Ministry of Health and included K. pneumoniae ATCC 700324, A. baumannii ATCC 17978, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853.

Carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (CRKP), carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB), and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (CRPA) were defined as isolates resistant to imipenem or meropenem based on the aforementioned CLSI guidelines.

Environmental sampling

Environmental samples were randomly collected from inanimate surfaces and the hands of healthcare workers (HCWs) at the end of each month, with the exception of February 2020 due to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Each month, 45 samples were taken (increased to 65 samples from August 2022 onward) from the ICU. The following environmental surfaces were frequently swabbed: (1) bed units for nonisolated patients (e.g., bed rail, bedside table, call button, patient record folder); (2) medical devices for nonisolated patients (e.g., infusion pump, touch pad for vital signs, touch pad or tubing surface for ventilators, stethoscope); (3) doctors’ offices and nurses’ stations (e.g., hand washing sink, computer keyboard or mouse, printer, landline telephone, drinking fountain, microwave); and (4) HCWs’ work coats, mobile phones, and hands.

The Hygiene Standard for Infections in Hospitals (GB 15982 − 2012) was followed when the sampling procedure was carried out for both inanimate surfaces and hand samples. A sterile cotton swab moistened with physiological saline (0.9% w/v) was moved back and forth over the surface of the inanimate object five times while the swab was rotated. For larger areas, the wiped area was 100 cm2; for areas below this threshold, the entire area was sampled. When collecting samples from the hands of HCWs before they washed them, a sterile cotton swab moistened with normal saline was passed twice over the flexed surfaces of the fingers of both hands from the base of the fingers to the fingertips while the swab was rotated. The portion touched by the collector’s hand was removed, and the remaining portion was placed in a test tube containing 10 ml of sterile saline.

Environmental Microbiological methods

One milliliter of sample solution was taken from the well-shaken test tube to inoculate the brain heart infusion (BHI) agar plate, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. The isolates on the BHI agar plate were identified as K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, or P. aeruginosa using a fully automated Vitek 2 COMPACT microbiology system (BioMerieux, Craponne, France). For antimicrobial susceptibility testing, the identified isolates were inoculated on Mueller-Hinton agar with two papers each containing 10 µg of imipenem or 10 µg of meropenem. CRKP, CRAB and CRPA were identified by the K-B paper disk diffusion test based on the CLSI M100 29th-32nd guidelines. Quality control was performed using the standard strains K. pneumoniae ATCC 700324, A. baumannii ATCC 17978, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 27. Categorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups were performed using the chi-square test, while the correlation between the number of positive GNB or CR-GNB isolated monthly from environmental and clinical samples was analyzed using Spearman’s correlations, with p < 0.05 considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

GNB and CR-GNB from clinical specimens

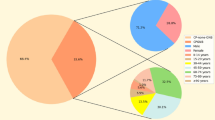

Between 2019 and 2022, 5,097 routine clinical specimens were collected for diagnostic purposes from patients admitted to the ICU. Among these, 898 (17.6%) GNB isolates were identified, predominantly comprising K. pneumoniae (401 strains). Additionally, 405 (8.0%) CR-GNB isolates were identified, with CRAB being the most prevalent (282 strains). Significant differences were observed in the distributions of both the three major GNB (χ2 = 142.640, p < 0.001; Fig. 1a) and the three major CR-GNB (χ2 = 360.422, p < 0.001; Fig. 1b) isolated from clinical specimens. Additionally, significant variations occurred in the isolation rates of A. baumannii, CRAB, and CRKP across the four study years (2019–2022), as presented in Table 1.

Overall percentages of GNB and CR-GNB isolates from the ICU clinical specimens from 2019 to 2022. GNB: gram-negative bacteria; CR-GNB: carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. (a): A comparison of A. baumannii (36.6%, 329/898), P. aeruginosa (18.7%, 168/898), and K. pneumoniae (44.7%, 401/898) isolated from clinical specimens revealed a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 142.640, p < 0.001). (b): A comparison of CRAB (69.6%, 282/405), CRPA (16.1%, 65/405), and CRKP (14.3%, 58/405) isolated from clinical specimens revealed a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 360.422, p < 0.001).

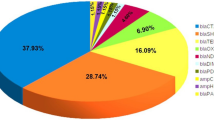

GNB and CR-GNB from environmental samples

From 2019 to 2022, 2,215 environmental samples were collected from inanimate surfaces and the hands of HCWs in the ICU. A total of 144 (6.5%) GNB were isolated, with A. baumannii predominating (75%; 108/144), followed by K. pneumoniae (13.2%; 19/144) and P. aeruginosa (11.8%; 17/144). A significant difference was observed in the percentages of the three GNB (χ2 = 168.813, p < 0.001; Fig. 2a). Similarly, 90 (4.1%) CR-GNB were detected, comprising CRAB (80%, 72/90), CRPA (15.6%, 14/90), and CRKP (4.4%, 4/90), with significant variation among these CR-GNB types (χ2 = 134.800, p < 0.001; Fig. 2b). Temporal analysis revealed significant yearly variations in most isolates’ prevalence (2019-2022), except for K. pneumoniae (χ2 = 3.977, p = 0.264) and CRKP (χ2 = 0.035, p = 0.998) (Table 2).

Overall percentages of GNB and CR-GNB isolates from the ICU environmental samples from 2019 to 2022. GNB: gram-negative bacteria; CR-GNB: carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. (a): A comparison of A. baumannii (75%, 108/144), P. aeruginosa (11.8%, 17/144) and K. pneumoniae (13.2%, 19/144) isolated from environmental samples revealed a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 168.813, p < 0.001). (b): A comparison of CRAB (80%, 72/90), CRPA (15.6%, 14/90), and CRKP (4.4%, 4/90) isolated from environmental samples revealed a statistically significant difference (χ2 = 134.800, p < 0.001).

Detection rates of CR-GNB in clinical and environmental samples

The detection rates of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria were 45.1% in clinical and 62.5% in environmental samples. Among these, CRAB showed persistently high resistance in both settings (85.7% vs. 66.7%). Notably, the environmental resistance proportions for CRPA and CRKP were 82.4% and 21.1%, respectively, which were elevated compared to their clinical rates of 38.7% and 14.5%.

Sampling sites in GNB- and CR-GNB- positive environments

Environmental surveillance conducted in the ICU between 2019 and 2022 identified 144 GNB isolates (positive rate: 6.5%) and 90 CR-GNB isolates (positive rate: 4.1%). As detailed in Table 4, contamination distribution analysis revealed that bed units of nonisolated patients accounted for 8.3% of GNB isolates (4.3% CR-GNB), medical devices of nonisolated patients for 7.0% (5.8% CR-GNB), doctors’ offices or nurses’ stations for 5.9% (3.6% CR-GNB), HCWs’ work coats for 9.1% (6.8% CR-GNB), mobile phones for 6.1% (4.1% CR-GNB), and hands for 5.0% (2.0% CR-GNB).

The detection rates of GNB and CR-GNB in the bed units of nonisolated patients were lower in rooms after terminal disinfection (7.6% and 3.4%) than in rooms occupied by patients (8.7% or 4.7%), though differences were not statistically significant (GNB: χ2 = 0.128, p = 0.720; CR-GNB: χ2 = 0.367, p = 0.545). Similarly, no significant differences emerged between in-use and disinfected medical devices for GNB (8.3% vs. 4.6%; χ2 = 1.497, p = 0.221) or CR-GNB (7.3% vs. 2.8%; χ2 = 2.794, p = 0.095). Notably, hand washing sink in doctors’ offices and nurses’ stations exhibited the highest contamination rates (GNB:19.6%; CR-GNB:16.3%), significantly greater than that non-hand washing sinks (GNB: χ2 = 33.546, p < 0.001; CR-GNB: χ2 = 46.258, p < 0.001). P. aeruginosa (14 strains) and CRPA (12 strains) predominanted in hand washing sinks.

Correlations between the number of positive GNB or CR-GNB strains isolated from environmental and clinical samples per month

A significant positive correlation was observed between the number of positive A. baumannii (Spearman’s rho = 0.505, p < 0.001; Fig. 3a) isolated from environmental samples and clinical specimens per month. Notably, this association was similarly pronounced for CRAB (Spearman’s rho = 0.368, p = 0.011;Fig. 3b). However, this significant positive correlation was not observed in other GNB (P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae) or other CR-GNB (CRPA and CRKP).

Discussion

Our study is the first 4-year comprehensive surveillance study to describe and analyze all isolated GNB and CR-GNB strains from environmental and clinical samples in the ICU of a tertiary university medical center in Changsha. Our results revealed that GNB and even CR-GNB can be detected in nonisolated patient environments and devices as well as in doctors’ offices and nurses’ stations, with CRAB being the predominant CR-GNB. In other words, GNB and CR-GNB contaminate the ICU through cross-transmission. The issue of environmental contamination may pose an even greater challenge in the ICU, where immunocompromised critically ill patients are often subjected to a variety of invasive diagnostic procedures and treatments15.

Few studies have examined environmental contamination outside of isolated patient areas. However, one study that sampled the surroundings of patients with positive CRAB clinical cultures within 7 days found a contamination rate ranging from 19% to 60.7%15, which is significantly higher than the contamination rate in environments outside isolated patient areas (CR-GNB: 4.1%) in our study. Additionally, Li K et al. conducted dynamic monitoring over the course of a year using 16 S rRNA sequencing to analyze bed units and medical devices before disinfection, revealing that Acinetobacter was consistently abundant in ICU environments16. When HCWs tend to isolated and nonisolated patients or walk from a contaminated hospital environment to the vicinity of nonisolated patients, they can potentially spread bacteria horizontally through their hands. The environment is a reservoir of microorganisms that can be transmitted to nonisolated patients via hands and invasive devices. Thus, to stop the spread of GNB, especially CR-GNB, in the ICU, environmental facility disinfection and stringent hand hygiene are crucial for HCWs.

However, after four years of environmental surveillance, we found that GNB could be isolated from disinfected bed units and medical devices of nonisolated patients. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in the detection rate of either GNB or CR-GNB between the pre- and postdisinfection periods. This is believed to be due to insufficient disinfection, which is typically performed through manual wiping with disinfectants and wipes for bed units and medical devices in our ICU. On the one hand, a study has shown that it is difficult to remove or eradicate environmental bacteria through contact disinfection of the environment17. Currently, an increasing number of studies have shown that ultraviolet light disinfection is superior to environmental contact disinfection and reduces environmental contamination18,19. Consequently, the use of no-touch environmental disinfection, for example, with ultraviolet light, is recommended for the terminal disinfection of bed units in ICU. On the other hand, low pay, heavy workloads, and high staff turnover among environmental services staff have contributed to lapses in adhering to cleaning and disinfection protocols. Ensuring a stable workforce, providing adequate supplies and equipment, and offering more training and supervision can improve compliance and reduce HAIs20. These factors will be the focus of our subsequent IPC program.

Hand hygiene is a cost-effective, convenient and effective way to protect individuals and prevent the transmission of pathogens21. However, we isolated 5% (5/101) of the GNB strains from the hands of HCWs, with one CRAB strain and one CRKP strain. This rate is consistent with the isolation rate of GNB from the hands of HCWs (7.6%) reported in a previous study but with different causative organisms (mainly P. aeruginosa)22.Notably, despite surveillance data showing an overall hand hygiene compliance rate of 76.0% (with annual fluctuations ranging from 71.7 to 84.2%) during the study period, the detection rates of GNB and CR-GNB on the mobile phones of HCWs were 5.4% and 4.1%, respectively, predominantly A. baumannii. A study on bacterial colonization on mobile phones and hands of HCWs showed that four (3.6%) and five (4.5%) strains of A. baumannii were detected on these, respectively, indicating cross-contamination between mobile phones and hands of HCWs23. In addition, we isolated 72 strains of GNB, 44 of which were CR-GNB, from doctors’ offices and nurses’ stations; the surfaces included hand washing sinks, computer keyboards or mice, printers, landline telephones, drinking fountains, and microwaves. HCWs may be less likely to adhere to hand hygiene guidelines when working in nonpatient areas such as doctors’ offices or nurses’ stations, which are perceived to be safer than patient environments. Therefore, strict hand hygiene is vital, and the disinfection of mobile phones must be taken seriously in the ICU.

A 2021 report from the China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS) stated that K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, Escherichia coli, and P. aeruginosa were the most common clinical isolates from the ICU. The resistance rates of these four bacteria to carbapenems were 20.6%, 78.2%, 3.5%, and 28.7%, respectively24. This finding is comparable to that in our clinical study, which showed that the GNB isolates and the CR-GNB isolates from clinical specimens were dominated by K. pneumoniae and CRAB, respectively. However, the predominant GNB isolated from environmental samples did not coincide with the clinical specimens in this study, and the most common isolate from the environmental samples was A. baumannii. This conclusion conflicts with those of previous studies in which K. pneumoniae or P. aeruginosa were the main GNB isolated from the surrounding environment and equipment25,26; however, these findings are consistent with those of other studies on contaminating bacteria in the ICU27,28,29. The isolation of distinct bacteria from surfaces in various healthcare settings may be connected to locally prevalent strains as well as the type of objects or equipment sampled. As in this study, hand washing sinks were the primary site of P. aeruginosa detection, while other objects or devices were the primary site of A. baumannii detection. Given that most of the limited P. aeruginosa isolates were obtained from washbasins, this sampling bias may explain the notably high detection rate of CRPA.

Finally, we further found a positive correlation between the number of A. baumannii or CRAB strains isolated per month from both the environmental and clinical samples via Spearman’s correlation analysis. In other words, the greater the number of patients with positive A. baumannii or CRAB isolated, the more contaminated the environment was with A. baumannii or CRAB. Notably, despite maintaining 85–90% compliance with surface cleaning protocols in the hospital during the study period, persistent CRAB contamination was still observed. The predominance of A. baumannii in the hospital environment is likely attributable to its remarkable capacity to survive on dry surfaces and its typically resistance to common disinfectants30,31. Based on these findings, we recommend implementing enhanced disinfection measures in areas surrounding wards treating CRAB-positive patients.

We also note that the observed increase in clinical CR-GNB isolates from 2020 coincides with multiple reports documenting a rise in healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance during the COVID-19 pandemic32,33,34. This trend is logically extended to our environmental findings: the concurrent rise in environmental CR-GNB isolates likely reflects this heightened clinical prevalence, as an expanded reservoir of colonized or infected patients would be expected to contribute to increased environmental contamination.

This study had several limitations. First, the absence of molecular genotyping for environmental and clinical isolates precludes confirmation of their clonal relatedness, despite the observed significant temporal correlations. Furthermore, the classification of “non-isolated” areas might have been influenced by undetected patient colonization. Second, E. coli was not included among GNB in the present study due to the low detection rate of carbapenem-resistant E. coli in clinical specimens. Third, as a single-center study conducted in a regional core hospital, the generalizability of our findings may be limited since the distribution and prevalence patterns of CR-GNB exhibit significant geographic variation across different regions and healthcare settings. Finally, the absence of recognized outbreaks linked to the target pathogens meant that no targeted interventions (e.g., no-touch disinfection or sink upgrades) were introduced. This lack of escalation in control measures may have contributed to the environmental persistence and the observed pattern of endemic circulation of CR-GNB in the ICU; however, we plan to implement improvements to reduce environmental contamination and cross-infection based on the key findings of this study.

Conclusions

In summary, this study primarily demonstrated that CR-GNB, particularly CRAB, contaminate the ICU environment beyond the immediate vicinity of isolated patients, likely mediated through cross-transmission. The prevalence and clinical significance of these environmentally persistent strains within hospitals remain inadequately characterized. Given the immunocompromised status of ICU patients and their frequent requirement for invasive procedures, we recommend implementing environmental contamination monitoring for CR-GNB (with emphasis on CRAB) in ICU settings. Key monitoring targets should include bed units, medical devices, and sinks to guide and evaluate the effectiveness of targeted cleaning and disinfection protocols.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- A. baumannii :

-

Acinetobacter baumannii

- ATP:

-

Adenosine Triphosphate

- BHI:

-

Brain heart infusion

- CLSI:

-

Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute

- CRAB:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

- CR-GNB:

-

Carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria

- CRKP:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae

- CRPA:

-

Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- GNB:

-

Gram-negative bacteria

- HAIs:

-

Healthcare-associated infections

- HCWs:

-

Healthcare workers

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IPC:

-

Infection prevention and control

- K. pneumonia :

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- P. aeruginosa :

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- RLU:

-

Relative light units

References

Zhai, W. et al. Presence of mobile Tigecycline resistance gene tet(X4) in clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0108121. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01081-21 (2022).

Tacconelli, E. et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3 (2018).

Jean, S. S., Harnod, D. & Hsueh, P. R. Global threat of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 823684. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.823684 (2022).

Karakonstantis, S., Kritsotakis, E. I. & Gikas, A. Pandrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: a systematic review of current epidemiology, prognosis and treatment options. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 75, 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz401 (2020).

Suleyman, G., Alangaden, G. & Bardossy, A. C. The role of environmental contamination in the transmission of nosocomial pathogens and healthcare-associated infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 20, 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-018-0620-2 (2018).

Correa-Martinez, C. L., Tönnies, H., Froböse, N. J., Mellmann, A. & Kampmeier, S. Transmission of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in the hospital setting: Uncovering the patient-environment interplay. Microorganisms 8, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8020203 (2020).

Casini, B. et al. Implementation of an environmental cleaning protocol in hospital critical areas using a UV-C disinfection robot. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20, 4284. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20054284 (2023).

Bouguenoun, W. et al. Molecular epidemiology of environmental and clinical carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacilli from hospitals in Guelma, algeria: multiple genetic lineages and first report of OXA-48 in Enterobactercloacae. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 7, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2016.08.011 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Comprehensive surveillance and sampling reveal carbapenem-resistant organism spreading in tertiary hospitals in China. Infect. Drug Resist. 15, 4563–4573. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S367398 (2022).

Protonotariou, E. et al. Polyclonal endemicity of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in ICUs of a Greek tertiary care hospital. Antibiot. (Basel). 11, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11020149 (2022).

Falcone, M. et al. Predictors of outcome in ICU patients with septic shock caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase–producing K. pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 444–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.01.016 (2016).

Schechner, V., Lerner, A. O., Temkin, E. & Carmeli, Y. Carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii load in patients and their environment: the importance of detecting carriers. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 44, 1670–1672. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2023.39 (2023).

Russotto, V., Cortegiani, A., Raineri, S. M. & Giarratano, A. Bacterial contamination of inanimate surfaces and equipment in the intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care. 3, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-015-0120-5 (2015).

Ahmed, E. H., Hassan, H. M., El-Sherbiny, N. M. & Soliman, A. M. A. Bacteriological monitoring of inanimate surfaces and equipment in some referral hospitals in Assiut City, Egypt. Int. J. Microbiol. 2019, 5907507. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5907507 (2019).

Nutman, A., Lerner, A., Schwartz, D. & Carmeli, Y. Evaluation of carriage and environmental contamination by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Microbiol Infect. ;22:949.e5-949.e7. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.08.020

Li, K. et al. Monitoring microbial communities in intensive care units over one year in China. Sci. Total Environ. 10 (811), 152353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152353 (2022).

Eckstein, B. C. et al. Reduction of clostridium difficile and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus contamination of environmental surfaces after an intervention to improve cleaning methods. BMC Infect. Dis. 7, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-7-61 (2007).

Morikane, K. et al. Clinical and Microbiological effect of pulsed Xenon ultraviolet disinfection to reduce multidrug-resistant organisms in the intensive care unit in a Japanese hospital: a before-after study. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-4805-6 (2020).

Villacís, J. E. et al. Efficacy of pulsed-xenon ultraviolet light for disinfection of high-touch surfaces in an Ecuadorian hospital. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 575. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4200-3 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Impact of environmental cleaning on the colonization and infection rates of multidrug-resistant acinetobacter baumannii in patients within the intensive care unit in a tertiary hospital. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 10, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-020-00870-y (2021).

World Health Organization WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care. (2009). http://www.who.int/infection-prevention/publications/hand-hygiene-2009/en/

Wang, H. P. et al. Antimicrobial resistance of 3 types of gram-negative bacteria isolated from hospital surfaces and the hands of health care workers. Am. J. Infect. Control. 45, e143–e147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2017.06.002 (2017).

Yao, N. et al. Bacterial colonization on healthcare workers’ mobile phones and hands in municipal hospitals of Chongqing, china: cross-contamination and associated factors. J. Epidemiol. Glob Health. 12, 390–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-022-00057-1 (2022).

China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. ;22:3370-9. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance reports from intensive care units from China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System in 2021. Chin J Nosocomiol (2023). https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.3436.R.20231020.1119.054

Sui, Y. S. et al. Effectiveness of bacterial disinfectants on surfaces of mechanical ventilator systems. Respir Care. 57, 250–256. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.01180 (2012).

Roux, D., Aubier, B., Cochard, H., Quentin, R. & van der Mee-Marquet, N. HAI prevention group of the Réseau des Hygiénistes du centre. Contaminated sinks in intensive care units: an underestimated source of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the patient environment. J. Hosp. Infect. 85, 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2013.07.006 (2013).

Whittington, A., Whitlow, G., Hewson, D., Thomas, C. & Brett, S. Bacterial contamination of stethoscopes on the intensive care unit. Anaesthesia 64, 620–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05892.x (2009).

Munoz-Price, L. S. et al. Associations between bacterial contamination of health care workers’ hands and contamination of white coats and scrubs. Am. J. Infect. Control. 40, e245–e248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2012.03.032 (2012).

Levin, P. D. et al. Contamination of portable radiograph equipment with resistant bacteria in the ICU. Chest 136, 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-0049 (2009).

Piperaki, E-T., Tzouvelekis, L. S., Miriagou, V. & Daikos, G. L. Carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter baumannii: in pursuit of an effective treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 25, 951–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.014 (2019).

Popova, A. V. et al. Novel Fri1-like viruses infecting acinetobacter baumannii-vB_AbaP_AS11 and vB_AbaP_AS12-Characterization, comparative genomic Analysis, and Host-Recognition strategy. Viruses 9, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/v907018 (2017).

Langford, B. J. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe. 4 (3), e179–e191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(22)00355-X (2023).

Yang, X. et al. Global antimicrobial resistance and antibiotic use in COVID-19 patients within health facilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregated participant data. J. Infect. 89 (1), 106183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2024.106183 (2024).

Kariyawasam, R. M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis (November 2019-June 2021). Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 11 (1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-022-01085-z (2022).

Funding

This study was supported by the Youth Talent Support Project for the Development of Hospital Infection Discipline, Hospital Infection Control Branch, Chinese Preventive Medicine Association (No.YG-2024012900111) and the National Natural Science Youth Foundation of China (No. 2022M713512).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PX, HCH, SDL conceptualized and designed the study. CL, AHW, and FYZ collected data and analyzed data. HCH, XH, and CHL performed the statistical analysis and prepared all figures. Manuscript preparation and editing was performed by PX, HCH, SDL. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Liuyang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (approval number: 202400501). All participants in this study provided informed consent prior to their involvement. The purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits of the research were clearly explained in both written and verbal formats. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, P., Huang, HC., Li, C. et al. Environmental contamination of carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacteria away from isolated patients in intensive care unit: a comprehensive surveillance study. Sci Rep 16, 680 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30256-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30256-2