Abstract

To investigate the pro-healing effect of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) on mucosal wounds of recurrent aphthous ulcer (RAU) mice and its molecular mechanism. The RAU mouse model was created using chemical cauterization, and ulcerated tissue was collected to observe morphological changes. Network pharmacology identified potential targets and mechanisms. TNF-α and IL-6 levels in ulcer tissues were measured using IHC and ELISA. Western Blotting and RT-qPCR assessed protein and RNA expressions of TLR4, MYD88, NF-κB, and related factors. A CCK8 assay evaluated the effect of drug concentration on cell activity. Finally, molecular docking and CETSA confirmed the association between EGCG and key target molecules. EGCG has been proven to accelerate the healing of ulcers in ICR mice. Meanwhile, EGCG improved the pathologic morphology of the oral mucosa in mice. A network pharmacological analysis of EGCG’s impact on RAU may be associated with the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Simultaneously, the levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and the expressions of TLR4, MyD88, p-IKB-α, and p-NF-κBP65/NF-κB P65, NF-κB 1 were decreased. The level of IKB-α was elevated, Showing dose dependence. The EGCG-H group showed better results than the positive control group; EGCG was tightly bound to TLR4 and NF-κB p65 target proteins. In conclusion, EGCG promotes the healing of oral ulcers in RAU mice and increases collagen fiber volume fraction in ulcerated skin tissue. The mechanism may be associated with reducing TNF-α and IL-6 expression levels and inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mouth ulcers are a common chronic disease that affects the oral mucosa. In clinical practice, they are also referred to as recurrent aphthous ulcers (RAU) or recurrent mouth ulcers. RAU is caused by systemic diseases or trauma, such as vitamin deficiencies, disorders of the oral microbial system, hematologic factors, stress, genetic diversity, and oxidative-antioxidant imbalances1. Its prevalence is as high as 20%, making it the most common oral mucosal disease2. The disease’s complex aetiology and pathogenesis make it difficult to explain using a single mechanism. Additionally, they tend to recur and currently have no effective treatment available. This significantly impacts the quality of life for patients suffering from this condition3. In clinical practice, topical corticosteroids, anaesthetics, analgesics, and systemic immunosuppressive therapy are frequently used to manage mouth ulcers in patients experiencing frequent or severe episodes4. However, long-term use of these drugs may result in drug resistance, immune imbalance, and other toxic side effects5,6. Pharmaceuticals derived from natural sources offer significant cost-effectiveness and safety advantages compared to traditional synthetic drugs. Therefore, it is an important research direction to explore effective and natural drug treatment for RAU.

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a medicinal plant component of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), is a polyphenol from green tea extracts. This ingredient is easy to obtain and has no obvious adverse reactions. In addition, it exhibits a broad range of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antifibrotic, anti-remodeling, and tissue-protective properties and can be used to treat a wide range of diseases7. However, the impact of EGCG on RAU has not been investigated. The formation of ulcers is frequently accompanied by inflammation. Toll-like receptors (TLRs) stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory mediators upon recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns; the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) family of molecules plays a pivotal role in regulating the immune response and the early and various stages of the inflammatory response8.

In this study, we established a mouse model of chemically induced RAU and assessed the pharmacological effects of EGCG on RAU. Network pharmacological analysis was utilized to determine potential targets and pathways of EGCG. The results revealed that the mechanism is closely associated with inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), as well as the key role of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in this process, aiming to investigate the effect and possible mechanism of EGCG on RAU.

Materials and methods

Drugs and reagents

EGCG (98% purity, Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.); NaOH crystals (Biofroxx, Germany); isoflurane; sodium chloride injection; vitamin C tablets; vitamin B2 tablets; 4% paraformaldehyde (Wabcan Biotechnology Co., Ltd.); HE staining kit, Masson staining kit, Tween 20, Trizol (Solarbio); TNF-α, IL-6 ELISA kit (Wuhan Purity Biological Co., Ltd.); trichloromethane (Tianjin Tianli Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.); reverse transcription kit (Shanghai Yisheng Bio-technology Co., Ltd.); fluorescence quantification kit, BCA protein quantification analysis kit (Nanjing Novizen Bio-Tech Co., Ltd.); fluorescence quantification kit, BCA protein quantification analysis kit (Nanjing Novozymes Biotechnology Co., Ltd.); 5× protein sampling buffer (Biosharp); RIPA lysate (Biyuntian Biotechnology Co., Ltd.); PMSF, protein marker, HRP-goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody, GAPDH antibody (Servicebio); TLR4 primary antibody, MYD88 primary antibody, NF-κB p65 primary antibody, MYD88 primary antibody, NF-κB p65 primary antibody, p-NF-κB p65 primary antibody (Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology Co., Ltd.); IKB-α primary antibody, P-IKB-α primary antibody (Abmart Biotechnology Co., Ltd.).

Main instruments and equipment

Fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument, electrophoresis instrument, vertical electrophoresis tank, protein transfer tank, enzyme label instrument, gel imaging analyser (BIO-RAD Company); Automatic enzyme labeling instrument (Thermo Company, USA); Inverted optical microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan); High speed cryogenic refrigerated centrifuge (Eppendorf).

Establishment of oral ulcer model

50 SPF grade ICR mice, 6–8 weeks old, weighing about 20–30 g, half male and female, were enrolled from the Animal Center of Hubei Medical University, license No.: SCXK (E) 2019-0008. Feeding conditions: room temperature 22–25 °C, humidity 50–60%, 12 h alternating light and shade, no water limit. Animal experiments complied with the laws and institutional guidelines, and the protocol was approved by Hubei Medical College (Fu) No. 2024-Si 082 review approval number.

The mouse ulcer model was established by chemical cauterization9,10,11: after the mice anaesthetised by intraperitoneal injection of 1.25% Avertin (also known as 2,2,2-tribromoethanol;120 mg/kg ip), the 2 mm in diameter saturated NaOH crystals were picked up with tweezers, and the left lower lip of the mice was burned near the mucosa of the mouth corner for 5 s. After burning, the burned site was washed with 0.9% sodium chloride injection to remove residual NaOH, and the immediate reaction was recorded. The molding was observed after anesthesia for 24 h, during which water was fasting. There were noticeable chemical cautery marks in the treatment area, red and white damage of 2 mm in diameter on the surface mucosa, and the central depression of the wound and covered with white pseudo-film. Three mice were randomly selected before and after mold creation for histopathological examination.

Grouping and administration

Using the random number method, ten mice were selected as the normal control NC group, and the remaining 40 mice were used to establish the model. After successful modeling (24 h), the mice were randomly divided into four groups, ten mice in each group. They were divided into a negative control (RAU) group, a vitamin positive control (positive) group, a 150 mg/kg EGCG (EGCG-H) group, and a 75 mg/kg EGCG (EGCG-L) treatment group. The positive control group received a daily gavage of 0.01 mL/g of the positive reagent. In contrast, the normal and negative control groups were administered 0.01 mL/g of distilled water via gavage once daily for seven days.

Observe the healing of the ulcer surface and measure the area

Photographs were captured to document the healing process of ulcers, and the mean ulcer healing area was computed for each group. The ulcer area was quantified in mm² utilizing Image J software to assess the healing rate.

Construction of pharmacology network

The target protein names were sourced from the TCMSP database (https://www.tcmsp-e.com/). At the same time, the species “Homo sapiens” was selected from the UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/) database to facilitate the identification of potential target genes for EGCG. In NCBI’s GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), we searched with the keyword “oral ulcer,” Subsequently, datasets about the species “Homo sapiens” classified as “DataSets” were meticulously filtered. The datasets selected for analysis were distinguished by their substantial sample sizes and superior data quality. Intersecting target genes of EGCG and RAU were obtained using the Venny 2.1.0 platform (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/). The overlapping targets were used to construct a protein-a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network by STRING database (http://string-db.org/). The research species was defined as “Homo sapiens.”Cytoscape 3.9.1 is a software tool utilized to analyze and visualize topologies. The potential therapeutic targets were imported into the DAVID database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/tools.jsp) for gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gene and Genome (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis12,13,14,Threshold p < 0.05. In conclusion, molecular docking between EGCG and the core targets was conducted using AutoDock software15. Targets exhibiting favorable binding affinities were identified and visualized with PyMOL 2.4.016.

ELISA

The levels of inflammatory factors at the site of oral ulcers in mice were assessed using ELISA. Seven days post-drug administration, ulcerated mucosal tissues were excised and weighed, with five times the tissue weight added to PBS (pH 7.4). The specimens were then homogenized using a homogeniser. After approximately 20 min of centrifugation at 3000 rpm, the supernatant was meticulously collected and analyzed for IL-6 and TNF-α levels using ELISA kit instructions.

Pathological examination

After a seven-day treatment period, three mice from each group were randomly selected and euthanized through cervical dislocation. The ulcerated tissue was subsequently harvested for analysis. The tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin. The slices were cut into five µm, deparaffinised, and stained with HE and Masson to observe healing. IL-6 and TNF-α were detected by immunohistochemistry (IHC). After staining, the slides were sealed and photographed under a microscope. The distribution of collagen fibers was counted by Image J.S-P IHC staining with brown nuclei, which was positive. Image J was used to count the number of positive cells/fields, and three high-power fields were randomly selected from each group.

Western blot

After tissue grinding, RIPA lysate containing protein phosphatase inhibitors was added and lysed for 20 min on ice. After centrifugation at 12,000 RPM for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was fractionated, and the protein was quantified using the BCA kit. After 10%SDS-PAGE (concentration gel voltage 80 V, separation gel voltage 120 V), the membrane was rotated at 350 mA for 40 min. The rapid blocking solution was added and blocked at room temperature for 15 min; appropriate amount of anti-TLR4 (1:2000), MyD88 (1:2000), NF-κB P65 (1:3000) and P-selectin were added Primary antibody dilutions of NF-κB P65 (1:4000), IKB-α(1:1500), P-IKB-α(1:1500), and GAPDH (1:3000) were shaken at 4 °C overnight, After washing the membrane, the secondary antibody was incubated at room temperature for 90 min. The membrane was washed by TBST and exposed to an ECL chemiluminescence solution.

RT-qPCR

Trizon reagent was used to extract total RNA from ulcer tissue, and mRNA was extracted using an RNA ultrapure extraction kit. After reversing mRNA transcription into cDNA, gene expression was analyzed by fluorescence quantitative PCR. The program was set to predenaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Relative expression was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method using GAPDH as an internal control. The specific primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

CCK-8

A total of 2000 oral squamous cell carcinoma (CAL27) cells with 100 µL per well were spread in 96-well plates, and 100 µL PBS solution was added to the outer edge of 96-well plates. After completion, the 96-well plate was placed in the cell culture incubator overnight. The next day, the cell growth was observed, and the culture medium containing different concentrations of EGCG (0, 0.2 mM, 0.3 mM, 0.6 mM, 1.2 mM) was changed for 5 h, and the cell survival rate was evaluated by the CCK-8 method.

CETSA

CETSA was used to verify the binding of EGCG to potential protein targets17. Cultured CAL27 cells were treated with different concentrations of EGCG for 5 h, and the precipitated cells were resuspended in PBS and distributed to eight different PCR tubes with 100 µL of cell suspension in each tube. The cells were treated with heat, lysed by liquid nitrogen, and thermal cycling at 25 °C twice, and the soluble proteins were extracted. Finally, the soluble proteins were quantified by Western blotting with anti-target protein antibodies.

Statistical analysis of data

Statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prim 8, and data are expressed as mean ± SD. T test was used for comparison between two groups, ANOVA was used for comparison between multiple groups, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

EGCG promotes RAU healing in ICR mice

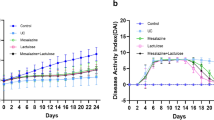

Figure 1A shows the basic flow chart of the mouse experiment.On day one, after modeling, all mice developed RAU, as shown in Fig. 1B; the oral mucosa of mice in the normal control group was pink in color, intact, smooth, and without ulcers. In the other groups, obvious ulcers appeared on the mucosa of the left lower lip near the corner of the mouth after NaOH cauterization for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 1C, There was no difference in the area of the ulcers between the groups(p > 0.05). After 4 days of administration of low and high doses of EGCG, mice exhibited decreased ulcer size, less severe ulcers, and less congestion and swelling; there was a notable reduction in congestion and edema in the adjacent mucosal tissue. Furthermore, several pseudomembranes had separated from the underlying surface. In stark contrast, the mucosa in the injury site of the EGCG-treated group exhibited features akin to that of healthy mucosa, devoid of any apparent congestion or edema. Compared with the RAU group, the ulcer area of the EGCG-H group, the EGCG-L group, and the positive control group was significantly reduced, and the wound healing rate was significantly increased on D1-D7 (p < 0.01). There was no significant difference in ulcer healing between the positive control and EGCG groups, but higher doses of EGCG showed a more favorable trend in ulcer healing (Fig. 1D). At the same time, the body weight of the mice in the normal group was stable, and the average body weight of all the mice in the model groups decreased; the most obvious decrease was observed in the RAU group. In contrast, the body weight of the EGCG-H group was slightly higher than that of the EGCG-L group (Fig. 1E).

EGCG favors the healing of oral ulcers. A Animal experiment flow chart. B Ulcer healing images of mice in each group. C The ulcer area of mice in each group at day 1, 4 and 7. D Ulcer healing area in each group D1–D7.Data were shown as mean ± SD (n = 3), Unit mm2. **p<0.01 vs. RAU group. E The following table shows the change in body weight of the mice in each group before (day 0) and 3, 5, and 7 days after Membrane making. Control: Normal control group; RAU: Ulcer model group; EGCG-H: EGCG-150 mg/kg group; EGCG-L: EGCG-75 mg/kg group; Positive: positive control group.

EGCG improved the pathological morphology of oral mucosa in mice

As observed by HE staining, the ulcer healing effect of EGCG and the positive control group was better, as shown in Fig. 2A. The oral mucosal epithelial tissue of the normal group was complete, and the structure was clear. After 24 h of cauterization in the other groups, a prominent round ulcer appeared on the left lower lip near the corner of the mouth. In the model group, the ulcerated area of the mucosal epithelium and lamina propria exhibited severe damage and fracturing, accompanied by a disorganized arrangement of cells, extensive infiltration of inflammatory cells in the submucosal layer, and notable extravasation of erythrocytes. In contrast, the treatment group exhibited a relatively compact and organized arrangement of connective tissue in the lamina propria of the epithelial tissue, with only mild damage to the stratum corneum and a clear structure in the remaining epithelial layer. Additionally, there was a notable reduction in the extravasation of erythrocytes, a significant decline in inflammatory cell infiltration, and a minor gap between the submucosa and the lamina propria. These findings indicate that EGCG has effectively bolstered the function of the mucosal barrier.

As shown in Fig. 2A, Masson’s Trichrome staining (MT) of collagen fibers was performed in mouse buccal mucosa ulcer tissue; in the mucosa of mice in the model group, the collagen fibers were disorganised and sparsely arranged. In contrast, in the ulcer tissue of the treatment group, the collagen fibers exhibited uniform and orderly increases compared to those in the model group. Figure 2B shows the quantitative analysis of collagen fibres in MT staining of ulcerated tissue.The results showed that EGCG was able to reduce collagen deposition in the RAU model, and the higher dose of EGCG showed a more significant effect, suggesting a dose-dependent manner.

Histopathological examination of the oral mucosa. A HE staining and MT staining of oral ulcer tissue in RAU mice. a: NC(Normal control group); b: RAU-DAY1(After 24 H of membrane formation); c: RAU group; d: EGCG-H group; e: EGCG-L group; f: positive(VC+VB) group (×100/×200 scale bar = 100 μm/50 µm); B volume fraction of collagen fibers in ulcerated tissue in MT staining. *p<0.05, vs. NC group; #p<0.05, vs. RAU group.

Prediction of targets and pathways by network Pharmacology technology

Firstly, the oral availability of EGCG was 55.09% (OB ≥ 30%), and the drug-like level was 0.77 (DL ≥ 0.18) after searching in the TCMSP database, compliance with routine requirements. At the same time, 124 drug targets corresponding to active compounds were integrated from TCMSP. Second, 8705 oral ulcer-related differential targets were collected in the GEO database (Fig. 3A–C). 71 intersection target genes of EGCG and RAU were obtained (Fig. 3D). The obtained intersection target genes were imported into the STRING database, and the 18 unconnected target genes in the hidden network were selected by PPI protein to get the PPI map of EGCG anti-RAU disease and the interacting genes (Fig. 3E). Then, the 53 genes were chosen for topological analysis and visual analysis. The darker the color, the more significant the correlation. IL-6, TLR4, IKB and other genes may be potential therapeutic targets (Fig. 3F).

Network pharmacology analysis was used to screen the potential core targets of EGCG on RAU diseases. A Gene distribution volcano. Plot B clustered UMA. Plot C sample normalization boxplot of dataset. D EGCG and RAU disease intersection gene Venn diagram. E EGCG-RAU disease target protein PPI interaction network diagram. F EGCG-RAU target intersection core network diagram.

GO and KEGG analysis: GO reveals the function of core genes in three ways; in biological process (BP), the primary genes were enriched in the negative regulation of the apoptosis process, cell response to mechanical stimulation, and I-κB kinase /NF-κB signal transduction; The cellular component (CC) mainly involved RNA polymerase II transcription factor complex, transcription factor complex, and interleukin-6 receptor complex. Molecular function (MF) primarily includes identical protein binding, protein serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase activity, enzyme binding, etc. The visualization of the GO analysis is shown in Fig. 4A. KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that the core target genes were primarily associated with various cancer-related pathways, as well as the tumor necrosis factor signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, IL-17 signaling pathway, and hepatitis B. Bubble plots depicting the degree of enrichment were generated (Fig. 4B). The comprehensive analysis of drugs’ physical and chemical properties, disease pathophysiological factors, and network pharmacological visualization revealed important pathways. Among these pathways, the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, which regulates inflammatory factors, was closely related to EGCG in the inflammatory response of RAU disease (Fig. 4C).

EGCG reduces the expression of TNF-α and IL-6 inflammatory factors in RAU mice

IHC was used to detect TNF-ɑ and IL-6 positive areas in the ulcer site of mice in each group, and the visual field ratio was calculated and analyzed (Fig. 5A–C). Compared with the NC group, the positive rates of TNF-ɑ and IL-6 in the RAU DAY1 and RAU groups were significantly increased (p < 0.0001). Compared with the RAU group, the positive rates of TNF-ɑ in the EGCG-H, EGCG-L, and positive groups were significantly decreased (p < 0.01), and the positive rates of IL-6 were significantly reduced (p < 0.05). The effect of EGCG on inflammatory factors was dose-dependent.

The expression levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the extracts of specimens from each group were determined by ELISA. Compared with the normal control (NC) group, the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the RAU DAY1 and RAU groups were significantly increased (p < 0.0001). Compared with the RAU group, the levels of IL-6 in EGCG-H, EGCG-L, and the positive group were significantly decreased (p < 0.0001). EGCG-H could dramatically reduce the TNF-alpha level (p < 0.0001), and EGCG-L and the positive group could reduce the TNF-alpha level (p < 0.01). There was no significant difference in inflammatory factors between the positive and EGCG groups, but the ECGG-H group had a more significant inhibitory effect on inflammatory factors. Meanwhile, the impact of EGCG on inflammatory factors was dose-dependent (Fig. 5D-E).

EGCG inhibits TNF-ɑ and IL-6 expression in mouse ulcer tissues. A–C The positive rates of TNF-ɑ and IL-6 in the ulcer sites of mice in each group were detected by IHC.(cale bar = 20/10 µm) n = 3. D, E ELISA was used to measure the expression of TNF-ɑ and IL-6 in the extract of each group: X ± S, unit pg/ml. n = 6. **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 vs. NC group; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001, ####p<0.0001 vs. RAU group.

EGCG inhibited the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway

Compared with the NC group, the protein expressions of TLR4, MyD88, p-Nf-κB p65/NF-κB p65, and p-IKB-α in the RAU group were increased (p < 0.01), while the protein expression of IKB-α was significantly decreased (p < 0.0001). Compared with the RAU group, the expression of MyD88 and p-IKB-α protein in the positive group was decreased (p < 0.05), and the expression of TLR4, MyD88, and p-IKB-α protein in the EGCG-H group was significantly decreased (p < 0.01). The expression of p-NF-κB p65/NF-κB 65 protein was decreased (p < 0.05), and the expression of IKB-α protein was significantly increased (p < 0.01). The protein expression of TLR4 and MyD88 in the EGCG-L group was significantly decreased (p < 0.01), and the protein expression of p-IKB-α was decreased (p < 0.05), while the protein expression of IKB-α was increased (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A, B). The results showed that EGCG could inhibit the expression of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB p65 proteins and promote the expression of IKB-α protein, which was involved in the regulation of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway.

RT-qPCR was used to verify the effect of EGCG on the mRNA expression levels of TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB1, and NF-κB p65 in the ulcer site of mice. The results showed that the expression of TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB 1, and NF-κB p65 mRNA was higher in the RAU group compared with the NC group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6C). Compared with the RAU group, the mRNA expressions of TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB 1 and NF-κB p65 in EGCG-H group were significantly decreased (p < 0.001); The mRNA expressions of TLR4, MyD88 and NF-κB p65 in EGCG-L group were decreased (p < 0.05); The mRNA expressions of MyD88, NF-κB1 and NF-κB p65 were decreased in positive group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6D). The results showed that EGCG inhibited TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway in a dose-dependent manner.

EGCG inhibits the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. A, B Expression levels of TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB p65, IKB-α, and their phosphorylated proteins in mouse ulcer tissues were detected by Western blot. C RT-qPCR was used to detect the mRNA expression levels of TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB1, and NF-κB p65 genes in ulcer tissue of mice before and after modeling. D RT-qPCR was used to detect the effects of different drugs on the mRNA expression levels of TLR4, MyD88, NF-κB1, and NF-κB p65 genes in the ulcer tissues of mice. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 vs. NC group; #p<0.05, ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001, ####p<0.0001 vs. RAU group; n = 3.

EGCG bound to the core targets

To further clarify the binding ability of EGCG to the core target, AutoDock software was used to dock EGCG to the core target. The 2D structure of EGCG is shown in Fig. 7A, and a smaller Affinity value indicates a more substantial binding ability. The binding energy of the compounds to the core target protein was lower than − 5 kcal mol−1, indicating that the two compounds had good binding ability8. As shown in Fig. 7C, the binding energy of EGCG and TLR4 was − 6.8941 kcal mol−1. EGCG formed conventional hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues ASP C: 99, THR A: 232, SER A: 207, ASN A: 156, and ASP A: 181. It forms a Pi-anion bond with ASP A: 209. It also forms a Pi-Alkyl group with the amino acid residue ARG C: 106. The binding energy of EGCG and NF-κB p65 was − 6.0153 kcal mol−1, and EGCG formed conventional hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues GLN A: 220, ARG A: 158, GLN A: 247, and LYS A: 218; it forms carbon hydrogen bonds with LYS A: 79 and GLN A: 29. It forms A Pi-Alkyl group with amino acid residues ALA A: 192, PHE A: 184, and PRO A: 182. The binding energy of EGCG and IKB was − 7.1239 kcal mol−1. EGCG formed conventional hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues ASN D: 145, ASN D: 182, ASP A: 294, GLU D: 153 and ASP A: 210. Ionic bonds were formed with ARG D: 143 and ARG A: 253. EGCG was predicted to bind to the related core targets with good binding ability.

In addition, the CCK-8 method was used to determine the effect of different concentrations of EGCG on the viability of CAL27 cells (Fig. 7B), and non-toxic drug concentrations were selected for CETSA technology. As illustrated in Fig. 7D, CETSA experiments were conducted, and a fitted curve analysis was performed through Western blot quantification. The results demonstrated that EGCG enhanced the thermal stability of TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB p65 target proteins, confirming the binding between EGCG and TLR4,MyD88,and NF-κB p65.

Discussion

RAU is the most common oral mucosal disease. Patients with RAU often have frequent attacks, expressed as severe pain at the site of the ulcer, which severely affects eating, drinking, and even mood and causes great difficulty in the patient’s daily life18. However, to date, its pathogenesis is not completely understood, and there is no satisfactory treatment19.

RAU treatment mainly aims to alleviate the inflammatory process of ulcers. Most commonly used medications can only provide partial relief, and frequent use can cause side effects20. There are expected to be very few studies on treating RAU with natural extracts. The use of natural products in treating RAU and preventing oral ulceration may be a promising avenue of research due to their minimal toxicity and side effects. For example21, Zhang Guomiao et al. established a model of oral ulcer by chemical burning with water extract of Sophora alopecium bark. The histomorphological changes were observed by HE staining, ELISA detected the levels of inflammatory factors in the serum of rats, and the spleen coefficient of rats was measured. The results showed that Sophora alopecium bark extract could reduce the degree of congestion and accelerate the healing of oral ulcers in rats. It has a therapeutic effect on oral ulcers in rats. A clinical study22 collected 72 patients with oral ulcers, which proved that purslane extract had a good clinical treatment effect on oral ulcers. A study23 conducted ulcer modeling on 20 New Zealand white rabbits, taking tensile strength, adhesion strength, and swelling index as response variables, and the results showed that the ulcer healing in the Bletilla striata group was significantly better than that in the control group on the 7th day.

Green tea has a variety of ingredients and functions. The latest research indicates that green tea is a rich source of biologically active substances, especially EGCG, constituting between 50% and 70% of the total catechins. It is the main active ingredient in green tea and plays a significant role in the beverage’s pharmacological effects24. EGCG exhibits important physiological and pharmacological properties such as anti-tumor, anti-infection, anti-radiation, improvement of lipid metabolism, anti-oxidation, and prevention of cardiovascular diseases25,26.

Prior research has demonstrated that EGCG can mitigate oral inflammation by modulating the oral microbiota27. However, no research has been conducted on the link between EGCG and RAU. In this present study, we found that applying EGCG improved symptoms, reduced inflammation, promoted ulcer healing, and improved feeding behavior in RAU mice. Using an experimental RAU model induced by chemical damage revealed that EGCG significantly decreased body weight changes, lessened ulcer severity, markedly decreased ulcer size, and accelerated wound healing in chemically aggressive ulcers. The results of HE and MASSON staining demonstrated that the histopathological morphology of the ulcers tended to integrity, with cells and collagen fibers displaying a systematic arrangement following EGCG administration. This indicates that EGCG has a significant therapeutic effect on RAU in mice.

The etiology and pathogenesis of RAU are complex. In this study, we collated data on oral ulcer disease and EGCG drug targets using disease and target databases. The GO biology enrichment analysis and KEGG enrichment pathway analysis results indicate that the EGCG amelioration of RAU is closely related to inflammation. It has been demonstrated that IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine that promotes IFN-γ production, T-cell differentiation, and B-cell immunoglobulin secretion. Consequently, it plays a vital role in host defense, bridging innate and adaptive immunity28. IL-6 elevation may inhibit angiogenesis and delay wound healing29. In the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, TLR4 acts as a membrane-bound receptor, and IL-6 is involved in the pro-inflammatory response. In the NF-κB pathway, IL-1β and IL-6 function as pro-inflammatory factors with cytotoxic effects30. TNF-α is a principal pro-inflammatory cytokine, typically secreted by activated T cells. Its level reflects the severity of inflammation, promoting the release of inflammatory factors that lead to immune damage31. Therefore, the present study employed ELISA and IHC to detect the levels of inflammatory factors in ulcer tissues. The findings indicated that EGCG reduced the expression of inflammatory factors, including TNF-α and IL-6, in a dose-dependent manner. This suggests that the mechanism by which EGCG promotes ulcer healing may involve inhibiting inflammatory factor expression.

Considering these results, the potential protective mechanism of EGCG against RAU was further explored. The inflammatory response plays a major role in the pathogenesis of oral ulcers. The TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway is a principal pathway that mediates the inflammatory response32. TLR functions as an immune mediator, binding pathogen molecules in a non-specific manner, initiating signal transduction, activating NF-κB, and triggering inflammation. TLR is reflected in many cells, and its high expression marks inflammation33,34. It has been demonstrated that the expression of TLRs in oral epithelial cells of RAU patients is higher than that of the healthy group35. TLR4 is capable of recognizing molecular signals from pathogens or injury. This is accompanied by dimerization and interaction with MyD1 via the Toll/IL-88 receptor homology region, forming a receptor-associated kinase that interacts with MyD88 and IL-1. This process leads to the release of TRAF6 into the cytoplasm, activating the IKK complex. This results in the activation of NF-κB and nuclear translocation, promoting the release of inflammatory factors that form a positive feedback loop that exacerbates inflammation36,37,38,39,40. In this study, we found the effect of EGCG on the expression of proteins and mRNAs related to the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway at the ulcer site in mice by Western blot and RT-qPCR experiments. The findings indicate that EGCG exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting this pathway.

EGCG, the main active ingredient in tea polyphenols, exhibits a strong antioxidant capacity due to its unique stereotypical structure and significant anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects7,41. It attenuates oral inflammation in mice by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. In order to study the binding properties of EGCG to key targets in greater depth, we conducted molecular docking and CETSA experiments, which demonstrated that EGCG forms stable complexes with core targets. EGCG has powerful affinities to two critical target proteins (NF-κB p65, IKB), and the primary forms of component-target interactions are hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces. Subsequently, CETSA experiments revealed that EGCG binds and stabilizes intracellular TLR4, MyD88, and NF-κB p65 target proteins.

Limitations

Of course, this study has a few limitations. The mouse oral ulcer model established utilizing chemical cauterization does not fully mimic the pathological process of recurrent aphthous ulcers in humans. Although this study revealed the therapeutic potential of EGCG on oral ulcers through pharmacodynamic evaluation and preliminary mechanism exploration, it should be pointed out that the results still need to be further verified by Toll-like receptor 4 gene knockout (TLR4 KO) animal model. Future studies will be further verified by the following aspects: TLR4 KO mice, bone marrow chimera experiment and primary cell gene silencing technology will be used to systematically verify the dependent effect of EGCG on TLR4 pathway and its cell-specific mechanism. These follow-up experiments will provide more direct evidence for the mechanistic hypothesis of this study and help elucidate the precise target of EGCG. Nevertheless, this study provides a new way and target for treating oral ulcers, and new drugs are supposed to be developed to prevent and treat oral ulcers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, EGCG was considered to be highly efficacious in the treatment of RAU in ICR mice. Its mechanism of action may be the inhibition of the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway, which in turn reduces the inflammatory response (Fig. 8).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.Data will be made available on request.To obtain data from this study, contact the XueDi You -2580450875@qq.com.

Abbreviations

- EGCG:

-

Epigallocatechin gallate

- RAU:

-

Recurrent aphthous ulcer

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin-6

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- RT-qPCR:

-

Real-time PCR

- TLR4:

-

Toll-like receptor 4

- MYD88:

-

Myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88

- NF-κB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-B

- NF-κBP65:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-B P65

- CCK8:

-

Cell counting Kit-8

- CETSA:

-

Cellular thermal shift assay

- IKB-α:

-

I-kappa-B-alpha

- p-IKB-α:

-

p-I-kappa-B-alpha

- WB:

-

Western blot

- p-NF-κBP65:

-

p-Nuclear factor kappa-B P65

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin eosin staining

- MASSON:

-

Masson’s trichrome stain

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gene and Genome

- PPI:

-

Protein-a protein–protein interaction

References

Suharyani, I., Fouad Abdelwahab Mohammed, A., Muchtaridi, M., Wathoni, N. & Abdassah, M. Evolution of drug delivery systems for recurrent aphthous stomatitis. DDDT 15, 4071–4089 (2021).

Sardaro, N. et al. Oxidative stress and oral mucosal diseases: an overview. In Vivo 33, 289–296 (2019).

Dudding, T. et al. Genome wide analysis for mouth ulcers identifies associations at immune regulatory loci. Nat. Commun. 10, 1052 (2019).

Hello, M., Barbarot, S., Bastuji-Garin, S., Revuz, J. & Chosidow, O. Use of thalidomide for severe recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a multicenter cohort analysis. Medicine 89, 176–182 (2010).

Eisen, D., Carrozzo, M., Bagan Sebastian, J. & Thongprasom, K. Number V oral lichen planus: clinical features and management. Oral Dis. 11, 338–349 (2005).

Manfredini, M. et al. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: treatment and management. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. e2021099 https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.1104a99 (2021).

Gan, R. Y., Li, H. B., Sui, Z. Q. & Corke, H. Absorption, metabolism, anti-cancer effect and molecular targets of Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG): an updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 58, 924–941 (2018).

Baud, V. & Derudder, E. Control of NF-κB activity by proteolysis. In NF-kB in health and disease (ed Karin, M.) vol 349 97–114 (Springer, Berlin, 2010).

Yin, S. et al. Therapeutic effect of Artemisia argyi on oral ulcer in rats. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 42, 824–830 (2017).

金钊 郑涛, 严航, 艾黄萍, & 左渝陵. 升麻增效口腔溃疡散治疗口腔溃疡大鼠模型的研究 中国中医基础医学杂志. 23, 1569–1572 (2017).

祝红 苗明三. 口腔溃疡动物模型造模方法及临床吻合度分析. 世界科学技术-中医药现代化 25, 1750–1756 (2023).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. K. E. G. G. Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Forli, S. et al. Computational protein–ligand docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nat. Protoc. 11, 905–919 (2016).

Hsin, K. Y., Ghosh, S. & Kitano, H. Combining machine learning systems and multiple Docking simulation packages to improve docking prediction reliability for network Pharmacology. PLoS One 8, e83922 (2013).

Jafari, R. et al. The cellular thermal shift assay for evaluating drug target interactions in cells. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2100–2122 (2014).

AL-Omiri, M. K. et al. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS): a preliminary within‐subject study of quality of life, oral health impacts and personality profiles. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 44, 278–283 (2015).

Saikaly, S. K., Saikaly, T. S. & Saikaly, L. E. Recurrent aphthous ulceration: a review of potential causes and novel treatments. J. Dermatol. Treat. 29, 542–552 (2018).

Prathoshini, M. Management of recurrent aphthous ulcer using corticosteroids, local anesthetics and nutritional supplements. Bioinformation 16, 992–998 (2020).

张国淼 et al. 槐白皮提取物治疗口腔溃疡大鼠的效果及对炎症因子的影响 中国医学创新 18, 14–19 (2021).

郑丽明 马齿苋提取物治疗口腔溃疡临床效果观察 深圳中西医结合杂志 28, 46–47 (2018).

Liao, Z., Zeng, R., Hu, L., Maffucci, K. G. & Qu, Y. Polysaccharides from tubers of Bletilla striata: physicochemical characterization, formulation of buccoadhesive wafers and preliminary study on treating oral ulcer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. Struct. Funct. Interact. 122, 1035–1045 (2019).

Khan, N. & Mukhtar, H. Tea polyphenols in promotion of human health. Nutrients 11, 39 (2018).

Chakrawarti, L., Agrawal, R., Dang, S., Gupta, S. & Gabrani, R. Therapeutic effects of EGCG: a patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 26, 907–916 (2016).

Xu, S. et al. Tea polyphenol modified, photothermal responsive and ROS generative black phosphorus quantum Dots as nanoplatforms for promoting MRSA infected wounds healing in diabetic rats. J. Nanobiotechnol. 19, 362 (2021).

Pan, Y. et al. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) alleviates the inflammatory response and recovers oral microbiota in acetic acid-induced oral inflammation mice. Food Funct. 14, 10069–10082 (2023).

Choy, E. H. et al. Translating IL-6 biology into effective treatments. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 16, 335–345 (2020).

Kang, S., Narazaki, M., Metwally, H. & Kishimoto, T. Historical overview of the interleukin-6 family cytokine. J. Exp. Med. 217, e20190347 (2020).

He, H., Genovese, K. J., Nisbet, D. J. & Kogut, M. H. Profile of toll-like receptor expressions and induction of nitric oxide synthesis by toll-like receptor agonists in chicken monocytes. Mol. Immunol. 43, 783–789 (2006).

Bo, Z. et al. Investigation on molecular mechanism of fibroblast regulation and the treatment of recurrent oral ulcer by shuizhongcao granule-containing serum. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 1–9 (2015).

Hu, N. et al. Phillygenin inhibits LPS-induced activation and inflammation of LX2 cells by TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 248, 112361 (2020).

Gallo, C., Barros, F., Sugaya, N., Nunes, F. & Borra, R. Differential expression of toll-like receptor mRNAs in recurrent aphthous ulceration. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 41, 80–85 (2012).

Li, X. X. et al. Cryptotanshinone from salvia miltiorrhiza bunge (Danshen) inhibited inflammatory responses via TLR4/MyD88 signaling pathway. Chin. Med. 15, 20 (2020).

Hietanen, J. et al. Recurrent aphthous ulcers—a toll-like receptor–mediated disease? J. Oral Pathol. Med. 41, 158–164 (2012).

Kumar, H., Kawai, T., & Akira, S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications.388, 621–625(2009).

Keating, S. E., Maloney, G. M., Moran, E. M. & Bowie, A. G. IRAK-2 participates in multiple toll-like receptor signaling pathways to NFκB via activation of TRAF6 ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33435–33443 (2007).

Lu, P. D. & Zhao, Y. H. Targeting NF-κB pathway for treating ulcerative colitis: comprehensive regulatory characteristics of Chinese medicines. Chin. Med. 15, 15 (2020).

Wang, N. et al. Expression and activity of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in mouse intestine following administration of a short-term high-fat diet. Exp. Ther. Med. 6, 635–640 (2013).

Zhu, Y. et al. Jinhua Qinggan granules attenuates acute lung injury by promotion of neutrophil apoptosis and Inhibition of TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 301, 115763 (2023).

Jin, C., Shen, S. & Zhao, B. Different effects of five catechins on 6-hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 6033–6038 (2001).

Funding

The present work was supported by the Surface Project of the Hubei Provincial Health Commission [Grant numbers ZY2019M037] and; the Innovative Research Program for Graduates of Hubei University of Medicine [grant numbers YC2024025].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

You. -The first author: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Funding.Shi.Data curation.Ren and Wang. Formal analysis. Zhao. -corresponding authors: Funding, projection, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal experiments complied with the laws and institutional guidelines, and the protocol was approved by Hubei Medical College (Fu) No. 2024-Si 082 review approval number. The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. The agent used for euthanasia in this experiment was isoflurane.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved of its submission to this journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, X., Shi, J., Ren, Z. et al. The study of the therapeutic effect and preliminary mechanism of EGCG on recurrent aphthous ulcer. Sci Rep 15, 45634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30341-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30341-6