Abstract

This study presents a novel adaptive model predictive control (AMPC) framework for robust lateral motion tracking in semi-autonomous vehicles operating under dynamically uncertain conditions. Traditional controllers often struggle to maintain stability and accuracy in the presence of nonlinear vehicle dynamics, time-varying parameters, and external disturbances. The proposed AMPC system integrates real-time parameter estimation via recursive least squares with a predictive optimization structure, allowing continuous adaptation to variations in vehicle mass, speed, and tire-road friction. A comprehensive simulation environment developed in MATLAB/Simulink was used to evaluate the AMPC across multiple scenarios, including aggressive lane changes, crosswind disturbances, and low-friction conditions (friction coefficient μ = 0.4). Quantitative comparisons with conventional model predictive control (MPC) and linear quadratic regulator (LQR) controllers demonstrate that AMPC achieves a 43% reduction in lateral tracking error and a 37% improvement in yaw angle root mean square error (RMSE), maintaining peak yaw errors below 0.275 radians even under severe disturbances. Steering control signals remain smooth and within actuator limits, with maximum steering rates under 0.48 rad/s. Additionally, a human-in-the-loop simulation confirmed the controller’s ability to handle delayed driver intervention (1–3 s) without compromising vehicle stability or trajectory tracking. These results validate AMPC’s superior robustness, adaptability, and real-time performance in managing complex lateral control tasks. The framework provides a scalable solution for enhancing safety and reliability in shared-control driving environments, addressing both technical and human-centric aspects of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are revolutionizing modern transportation systems through their potential to minimize human error, reduce environmental impact, and enhance overall road safety. These systems rely on advanced technologies such as radar, LiDAR, cameras, inertial measurement units (IMUs), and powerful onboard computing units to monitor the driving environment and make real-time decisions without human intervention1,2. However, while the future of full autonomy remains promising, the present reality is dominated by semi-autonomous vehicles (SAVs particularly those classified under Level 2 of the SAE autonomy framework. In these vehicles, control of longitudinal and lateral motion is shared between the automated system and a human driver, with the driver expected to remain attentive and intervene when necessary3. This hybrid mode of operation introduces significant engineering challenges, especially in ensuring safe and smooth transitions between human and automated control. The complexity of designing systems that respond reliably under varying driving scenarios is intensified by the unpredictable behavior of human drivers and the operational uncertainties present in real-world environments3,4.

A key aspect of ensuring vehicle safety and performance in SAVs lies in effective lateral motion control, which governs how the vehicle moves side to side, whether during lane changes, cornering, or obstacle avoidance. In contrast to longitudinal dynamics, which have been widely studied and controlled through features like cruise control and automated emergency braking, lateral dynamics remain more sensitive and difficult to predict due to their nonlinear behavior and dependence on external factors such as road curvature, tire-road interaction, and vehicle loading conditions5. The lack of precision in lateral control often manifests in poor lane-keeping, oversteering, or understeering conditions that can lead to discomfort or, worse, collisions6. This vulnerability is even more critical in SAVs, where driver overreliance on automation may delay appropriate manual corrections7,8. Thus, a robust lateral control strategy that adapts to dynamic driving conditions and interacts seamlessly with human supervision is essential for safe SAV deployment9,10.

The role of AV technologies in reducing traffic-related fatalities, of which over 90% are attributed to human error, is well established11. Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) enable SAVs to perceive and interpret the driving environment more accurately than human drivers by using integrated sensor arrays and fusion algorithms 12,13 . These systems can track lane boundaries, detect other vehicles, and estimate road friction in real time. As a result, they offer advantages in maintaining optimal speed, reducing unnecessary lane changes, and improving fuel efficiency14,15. However, lateral maneuvers under uncertain and rapidly changing conditions continue to expose weaknesses in current SAV systems. Situations such as abrupt lane changes in congested traffic, steering on wet or icy roads, and navigating sharp bends at high speed demand a highly responsive and predictive control system that can maintain stability and comfort16,17. The performance disparity between longitudinal and lateral control systems is now one of the major technical bottlenecks in advancing semi-autonomous driving technologies.

Lateral dynamics are inherently nonlinear and involve multiple interacting variables such as lateral displacement, yaw rate, and side-slip angle18. These variables are influenced by vehicle parameters such as mass distribution, speed, center of gravity, and by external conditions like road surface friction and geometry. Traditional modeling approaches, including the linear bicycle model and its nonlinear extensions, have been instrumental in capturing basic lateral behavior19,20. However, most of these models assume constant vehicle parameters and ideal conditions, limiting their effectiveness when the vehicle experiences load variations, velocity changes, or encounters environmental disturbances such as wind gusts or potholes21,22. For instance, a sudden increase in vehicle mass due to passengers or cargo can shift the center of gravity and increase inertia, which in turn affects turning radius and response time. Likewise, higher speeds amplify lateral forces, making steering control more sensitive. Controllers that fail to account for such dynamics risk performance degradation, instability, or loss of control during critical maneuvers23.

Adding further complexity is the human–machine interaction intrinsic to SAVs. Unlike fully autonomous vehicles, where the system maintains full control, SAVs depend on human supervision and intervention. This presents a dual challenge: the control system must remain robust to physical disturbances while also accommodating varying levels of human engagement24. Prolonged periods of automated driving can lead to driver complacency or drowsiness, reducing the likelihood of timely intervention during emergencies. Furthermore, transition latency, the time it takes for a driver to regain full control after being alerted25, poses a critical risk in scenarios requiring immediate action. Thus, control systems for SAVs must be not only technically accurate but also intuitively communicative, allowing for a gradual and understandable transition from automation to manual control26. Studies have proposed improvements in driver monitoring systems and interface design, yet relatively few have focused on how the underlying lateral control algorithm itself can support such transitions through adaptive performance degradation and feedback mechanisms27,28,29.

In response to these multi-dimensional challenges, this study proposes a novel Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework for lateral motion tracking in semi-autonomous vehicles. Unlike conventional control methods that rely on fixed-parameter models, the proposed approach explicitly accounts for dynamic variations in vehicle parameters such as mass and speed. By embedding parameter adaptation mechanisms into the model predictive control structure, the controller continuously updates its internal model and prediction horizon to better reflect real-time vehicle dynamics. This enables more accurate trajectory tracking, reduced lateral error, and improved stability under diverse operating conditions. Both linear and nonlinear vehicle dynamic models are formulated to evaluate the performance of the control strategy under different scenarios. The adaptive MPC approach is benchmarked against classical MPC and LQR controllers, with evaluation metrics including tracking accuracy, control smoothness, and robustness to disturbances such as road irregularities.

The novel contribution of this work lies in its integrated approach to modeling, adaptation, and control. By considering the full spectrum of real-world variability, vehicle speed changes, and unpredictable road conditions, the proposed system offers a practical advancement over existing methods that assume ideal or static parameters. Furthermore, the AMPC framework is designed with the shared-control nature of SAVs in mind, enabling smooth coordination between automated and human control actions. The system is capable of recognizing human intervention delays and adjusting control authority accordingly, thereby enhancing trust, safety, and usability. Simulations conducted in high-fidelity environments validate the performance of the proposed controller across a range of real-world maneuvering tasks, including emergency lane changes and steering on varying road surfaces.

In conclusion, this research addresses a critical gap in the lateral control of semi-autonomous vehicles by presenting an adaptive and predictive control solution that aligns with both the physical realities of driving and the behavioral aspects of human supervision. It contributes to the broader field of vehicle autonomy by offering a flexible, intelligent, and robust control framework suitable for current and future SAV systems. By improving lateral maneuverability and reducing control system vulnerability to dynamic disturbances, this work enhances the safety, comfort, and reliability of shared-control vehicles. Furthermore, the findings have potential implications for infrastructure design, regulatory policy, and the development of next-generation ADAS interfaces that better reflect the demands of real-world driving. As the transition toward fully autonomous vehicles continues, the importance of intelligent lateral control in semi-autonomous platforms becomes a societal imperative, making this contribution both timely and transformative.

Simulation setup

To evaluate the performance of the proposed Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) strategy for lateral motion tracking in semi-autonomous vehicles, a comprehensive simulation framework was developed. The simulation environment was constructed in MATLAB/Simulink due to its flexibility, real-time visualization capabilities, and extensive control design toolboxes. The simulation setup was designed to replicate realistic driving conditions and to capture the nonlinear behavior of vehicle lateral dynamics under time-varying parameters such as vehicle longitudinal velocity and unpredictable road conditions.

Vehicle modeling

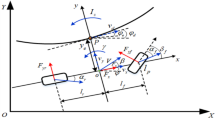

To comprehensively characterize the lateral motion behavior of the vehicle across a range of operational scenarios, this study employs a dual-modeling approach encompassing both kinematic and dynamic perspectives. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the kinematic model offers a simplified, geometry-based representation of the vehicle’s motion, ideal for efficient trajectory generation and path planning under conditions where tire slip and dynamic effects are minimal. Conversely, the dynamic model incorporates the effects of vehicle inertia, tire forces, and yaw dynamics, providing a more physically accurate framework essential for controller design and real-time simulation of vehicle behavior during aggressive maneuvers and variable road conditions. Together, these models facilitate a robust understanding and control of vehicle lateral dynamics, enabling the development of advanced vehicle control systems that are both computationally efficient and physically representative.

Kinematic bicycle model

The kinematic bicycle model is a simplified representation of a four-wheel vehicle that captures the essential geometric relationships governing its motion without accounting for tire forces or dynamics. It assumes negligible lateral tire slip, which is a valid approximation under low-speed conditions and for low lateral acceleration maneuvers. The model reduces the vehicle to two wheels: a front wheel responsible for steering and a rear wheel for propulsion.

Let (X, Y) denote the coordinates of the vehicle’s center of gravity (CG) in the global frame, and ψ represent the yaw angle (vehicle heading) relative to the global x-axis. The control inputs are the longitudinal velocity v and the steering angle δ, which is applied at the front wheel.

Nonlinear dynamic model and lateral-yaw coupling

While the kinematic model provides a simplified framework for low-speed motion, it fails to capture inertial effects, lateral tire forces, and yaw dynamics that become significant during aggressive maneuvers, high-speed turning, or external disturbances. Therefore, to develop and evaluate control algorithms under realistic conditions, a nonlinear dynamic bicycle model is adopted. This model captures the essential vehicle dynamics in the lateral and yaw directions while still retaining computational tractability. The dynamic bicycle model is based on Newton’s second law applied to the vehicle’s center of gravity (CG), considering lateral forces from the front and rear tires and the yaw moment due to these forces. The Eq. of motion in the lateral and yaw domains are given by:

The linearization from Eqs. (5–6) is based on the small-slip-angle assumption, which states that the tire lateral forces vary linearly with the slip angles (∣αf∣, ∣αr∣ < 5°|. This assumption is valid for normal driving maneuvers and for most high-speed cornering conditions where lateral acceleration remains below the tire saturation limit. In practice, as the slip angle increases at very high speeds, the tire force slip relationship becomes nonlinear; however, the adaptive component of the proposed AMPC compensates for such variations by continuously updating the cornering-stiffness parameters (Cf) through the RLS estimator. Hence, even when the small-angle assumption is slightly violated, the controller maintains acceptable prediction accuracy and stable yaw-rate tracking. For extremely aggressive cornering where ∣α∣ > 8° and tire saturation occurs the model accuracy degrades, and such conditions are beyond the operational scope considered in this study.

Substituting the force expressions into the motion Eq., we obtain the coupled nonlinear lateral and yaw dynamics:

The lateral vehicle dynamics are represented by a two-degree-of-freedom (2-DOF) bicycle model that considers the lateral velocity vy and yaw rate \(\dot{\psi }\) as the primary dynamic states. This simplified model neglects roll and pitch motions but accurately captures the essential lateral yaw coupling responsible for vehicle path-following and stability control. The 2-DOF formulation provides an appropriate balance between physical realism and computational efficiency, which is necessary for real-time predictive control design.

The lateral tire forces are assumed to vary linearly with slip angle within the small-angle range (∣α∣ < 5°|, and cornering stiffnesses are incorporated as equivalent front and rear coefficients Cf and Cr. Incorporating additional moment coupling between the sprung mass, unsprung mass, and tire forces, the dynamic behavior can be extended with the following nonlinear torque balance expression:

To formulate the AMPC, the nonlinear dynamic model is linearized around a nominal trajectory to obtain a time-varying state-space representation. The state vector includes the lateral deviation and yaw angle error dynamics:

The nominal vehicle parameters summarized in Table 1 provide the complete dataset for the 2-DOF model. These values were applied directly in the state-space formulation to generate the numerical A and B matrices for controller implementation.

Using the nominal vehicle parameters listed in Table 1, the values were substituted directly into the continuous-time state-space matrices to obtain the numerical forms of A and B. These matrices (Eq. 16) fully define the lateral–yaw dynamics and serve as the basis for the discrete-time model employed in the AMPC formulation.

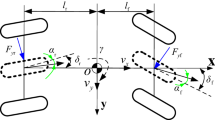

In this formulation, A(θ) and B(θ) explicitly depend on the parameter vector \(\theta =[Cf,Cr,m,Iz,lf,lr,\mu ],\) which is adaptively estimated online to capture dynamic variations. The disturbance input matrix E ensures robust compensation of external lateral and yaw disturbances. As illustrated in Fig. 2, this adaptive state-space model, structured in a tracking error formulation, effectively captures the lateral dynamic behavior of a semi-autonomous vehicle under varying operating conditions.

By continuously updating A(θ) and B(θ), the controller maintains precise lateral motion tracking performance despite uncertainties arising from changes in tire properties, load distribution, or road surface friction.

Adaptive model predictive controller design

This section outlines the development of an Adaptive Model Predictive Controller (AMPC) tailored for robust lateral motion tracking in semi-autonomous vehicles operating under dynamic and uncertain conditions. As depicted in Fig. 3, Model Predictive Control (MPC) offers a predictive, constraint-aware framework that optimizes control actions by solving a finite-horizon optimization problem at each sampling instant. In this study, the controller is enhanced with an adaptive mechanism that continuously updates the internal model based on real-time variations in vehicle mass, longitudinal speed, and tire-road friction. The AMPC leverages a linearized discrete-time state-space representation derived from a nonlinear bicycle model of the vehicle, which encapsulates the lateral displacement, yaw angle, and their respective derivatives.

The controller computes an optimal control sequence over a finite prediction horizon by minimizing a quadratic cost function that penalizes deviations from the reference trajectory and excessive control effort. Physical constraints on steering angle magnitude and rate are explicitly incorporated as inequality constraints to ensure safe and feasible actuation. To account for changes in vehicle dynamics, a recursive least squares (RLS) estimator is integrated into the control architecture, allowing real-time identification of key parameters such as mass and cornering stiffness. These updated parameters are used to adapt the system matrices used in the MPC formulation, ensuring model fidelity and robust performance. By combining prediction, optimization, constraint handling, and online adaptation, the AMPC ensures accurate lateral tracking even in the presence of disturbances, driver intervention delays, and parameter uncertainties. This design bridges the gap between theoretical control robustness and practical applicability in semi-autonomous vehicle systems, enhancing safety and stability in real-world driving conditions.

Prediction model formulation

The Adaptive Model Predictive Controller (AMPC) was formulated using a discrete-time state-space representation of the vehicle’s lateral and yaw dynamics, as defined in Eq. (17) and discretized in Eq. (18). This discrete-time model, derived from the linearized continuous-time vehicle dynamics, serves as the foundation for the adaptive MPC framework.

The continuous-time model

is discretized with a sampling period Ts to yield

where \(x_{k}\) the state vector is the steering input, and \(\left[ {v_{y} ,\dot{\psi }} \right]^{T} ,\,u_{k}\) represents external disturbances such as crosswind. The discrete matrices are computed from Eq. (19) converts the continuous dynamics to discrete form suitable for digital control implementation.

The predicted state sequence is generated recursively as Eq. 20–22

These relations describe how the future vehicle states evolve over the prediction horizon Np as a function of current state and future control inputs.

Compact prediction and cost function

For convenience, the predicted output vector can be expressed in a compact form as Eq. 23

where X stacks the predicted states and U stacks the future control moves.

The control objective of the MPC is to minimize a quadratic cost function that penalizes state-tracking errors and excessive control effort:

where Q and R , are positive-definite weighting matrices defined in Table 1.

The cost function can be rewritten in a compact matrix form as

H and f are the Hessian matrix and gradient vector of the optimization problem. Equation (28) represents the standard Quadratic Programming (QP) form solved at each sampling instant to obtain the optimal steering command sequence.

Quadratic programming (QP) formulation and constraints

The optimization problem in Eq. (28) can be expressed in a compact quadratic form, where the Hessian matrix H and the gradient vector f are defined as Eq. 29

The optimization seeks the future control sequence U that minimizes the cost J while satisfying steering and rate constraints.

To guarantee physical feasibility and passenger comfort, the steering angle δf and its rate of change are limited as Eq. 30

These constraints are compactly written in matrix form as Eq. 31 and the corresponding state input constraints can also be formulated as Eq. 32

Therefore, the constrained optimization problem solved by the adaptive MPC at each time step is expressed in Eq. 33

The first control action of the optimal sequence is then applied to the plant as model Eq. 34

while the remaining predicted inputs are discarded. This receding-horizon principle ensures closed-loop stability and real-time adaptability.

Recursive least squares (RLS) parameter update

To cope with changes in vehicle parameters during operation (due to load variation or tire stiffness changes), the system matrices Ad and Bd are adaptively updated through a Recursive Least Squares (RLS) estimator with an exponential forgetting factor λ.

The algorithm recursively updates the parameter vector θk and the covariance matrix Pk as modeled from Eq. (35–37):

The updated parameter vector θk directly modifies the state-space matrices Ad(θk) and Bd(θk) used in the MPC prediction model. This continuous adaptation allows the controller to maintain accurate internal prediction despite uncertainties in mass, tire stiffness, or road friction. Consequently, the adaptive MPC-RLS structure achieves real-time robustness to parameter drift and environmental changes.

Simulation scenarios, validation framework, and human-in-the-loop modeling

As illustrated in Fig. 4 the overall architecture of the adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework integrated with a Human-in-the-Loop (HIL) system. The AMPC generates the control signal (u) based on feedback from the vehicle and parameter estimates provided by the Recursive Least Squares (RLS) estimator. The RLS estimator continuously updates the model parameters (\(\theta\) k) using system response data, which enhances the controller’s adaptability to time-varying dynamics. The Delay block represents computational or communication delays inherent in the control loop, which are compensated by the AMPC to maintain performance. The HIL Delay block simulates human reaction and perception delays, providing a realistic interaction between human input and the automated control system. The vehicle model responds to the control input and external disturbance (Fw), producing measurable outputs for feedback. Overall, the closed-loop structure ensures real-time adaptation, robustness, and improved system stability under varying operating conditions.

To rigorously evaluate the performance, robustness, and adaptability of the proposed Adaptive Model Predictive Controller (AMPC), a comprehensive simulation framework was developed. This framework encompasses a series of scenarios reflecting diverse driving conditions, as well as a human-in-the-loop (HIL) simulation to assess shared control dynamics.

The simulation scenarios include:

-

Scenario 1: Straight-path tracking under nominal operating conditions (baseline vehicle mass and constant longitudinal velocity), serving as a reference for evaluating baseline trajectory tracking accuracy.

-

Scenario 2: Sudden lane-change maneuvers induced by sharp steering inputs, with vehicle speed varying between 20 and 25 m/s. This scenario assesses the controller’s ability to handle rapid lateral transitions and maintain stability at elevated speeds.

-

Scenario 3: Application of external disturbances such as lateral wind forces and yaw moment inputs to simulate environmental perturbations. This tests the AMPC’s disturbance rejection capabilities and robustness under unpredictable conditions.

The simulation experiments were conducted in the MATLAB/Simulink environment using a fixed-step discrete solver with a sampling period of Ts = 0.01 The nonlinear vehicle dynamics were integrated via the ode45 solver to ensure numerical stability and accuracy in continuous-time state propagation. The Adaptive Model Predictive Controller (AMPC) operated within a closed-loop configuration, incorporating real-time parameter adaptation through Recursive Least Squares (RLS) estimation and online quadratic optimization implemented via the MPC Toolbox. This architecture enables a realistic representation of system constraints, actuator dynamics, and transient vehicle responses under varying operating conditions.

To investigate the effects of shared-control transitions in semi-autonomous driving, a Human-in-the-Loop (HIL) simulation block was integrated between the driver-command module and the vehicle-controller interface. The HIL block introduces a predefined reaction delay (τd) representing the human response latency during system handover events. Based on empirical driver-behavior studies, τd was selected within the range of 1–3 s, corresponding respectively to an attentive and a delayed driver reaction. In each simulation scenario, the delay is modeled as a fixed constant to isolate the deterministic impact of communication latency on control performance. During this interval, the AMPC retains full lateral authority, ensuring stability and path adherence until manual steering intervention is re-established.

This modeling approach effectively emulates realistic driver–automation interaction dynamics and allows for systematic evaluation of controller robustness during transitional phases. Future research will extend this framework to incorporate stochastic and time-varying delay models, capturing the variability of human cognition and attention levels observed in naturalistic driving environments.

Result and discussion

This section presents and critically analyzes the simulation results obtained from the implementation of the Adaptive Model Predictive Controller (AMPC) across multiple driving scenarios. The primary objective is to evaluate the controller’s effectiveness in ensuring accurate lateral motion tracking, maintaining yaw stability, and responding appropriately under dynamically varying operating conditions. The scenarios include straight-line tracking under nominal conditions, aggressive lane changes at variable speeds, and external disturbances such as lateral wind forces and yaw moment perturbations.

By subjecting the AMPC to such conditions, the analysis highlights its robustness in handling challenges such as variable speed and external disturbances, which commonly affect the lateral dynamics of semi-autonomous vehicles. The results are interpreted using key performance indicators, including lateral error, yaw rate, and steering input response. Where applicable, performance improvements over conventional control strategies are also discussed. This comprehensive evaluation demonstrates the controller’s real-time adaptability and reliability, validating its potential for deployment in safety–critical automotive applications.

Vehicle responses under nominal conditions (μ = 1) without external disturbances

Under nominal driving conditions characterized by a high tire road friction coefficient (μ = 1), vehicle speed 20 m/s, no external lateral disturbances, and a constant vehicle velocity of 20 m/s, the performance of the proposed Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework was assessed against conventional Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) baselines. The evaluation focused on key lateral dynamic states and control effort to establish baseline controller behavior in ideal conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 5(A), the reference trajectory exhibits a sharp lateral transition, peaking around 5.4 m at 6.5 s, followed by a rapid return to zero lateral displacement. The AMPC response tracks this trajectory with high fidelity, demonstrating near-perfect alignment during both the ascent and descent phases. Relative to standard MPC and LQR, AMPC achieves the closest match to the reference, with reduced overshoot and faster convergence post-maneuver. This precision reflects the AMPC’s capacity to exploit accurate system knowledge in high-traction conditions, minimizing deviation without sacrificing control smoothness. And also, as depicted in Fig. 5(B), Yaw rate tracking performance, the AMPC output closely follows the reference profile, capturing the sharp negative to positive transition between 8 and 10 s with minimal phase lag. The MPC controller slightly overestimates the peak yaw rate, while LQR displays a slower and damped response, underestimating the dynamic transitions. AMPC’s superior tracking of high-frequency yaw rate variations indicates its robustness in replicating agile vehicle turning dynamics when stability margins are less constrained, as in high-μ conditions. Moreover, Fig. 5(C) evaluates yaw angle tracking performance; the reference curve exhibits a pronounced dip to –0.28 radians at approximately 9.5 s. AMPC responds swiftly and accurately, maintaining tight trajectory alignment. MPC (red dash-dot) performs comparably, though with slightly delayed peak alignment, while LQR lags considerably, failing to match the dynamic range of the reference. This highlights AMPC’s predictive horizon tuning and dynamic adaptability, allowing it to resolve sharp directional changes without inducing delay or instability. As indicated in Fig. 5(D), the steering control effort across the three strategies, AMPC, exhibits a higher amplitude input compared to MPC and LQR, peaking near ± 0.07 radians. Despite this, the control signal remains smooth and bounded, with no chattering or abrupt discontinuities. MPC (red dashed) delivers a more conservative input, while LQR maintains the lowest magnitude but at the expense of reduced tracking performance. AMPC’s control behavior reflects its optimized cost-balancing strategy, trading slightly higher input energy for superior trajectory tracking, demonstrating its suitability for real-time execution under nominal actuator constraints.

In general, Figs. 5(A–D) confirm that the proposed AMPC architecture outperforms conventional control strategies in trajectory tracking precision, responsiveness, and closed-loop stability under ideal conditions. The results establish AMPC as a high-performance baseline, capable of leveraging favorable road-tire interactions to achieve near-ideal vehicle motion tracking while maintaining bounded control inputs well within feasible actuator limits. This performance benchmark sets the foundation for subsequent evaluations under degraded conditions where robustness and adaptability become critical.

Vehicle responses under low-friction conditions (μ ≈ 0.4) without external disturbances

Under low-friction conditions (μ = 0.4) and a constant vehicle speed of 20 m/s, the performance of the proposed Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework was evaluated against conventional Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) controllers. The evaluation was conducted under idealized driving conditions, characterized by a low tire-road friction coefficient, no external lateral disturbances, and constant velocity, to analyze key lateral dynamic states and control effort, thereby establishing baseline controller behavior.

As shown in Fig. 6(A), the lateral position tracking performance of the vehicle operating under low-friction conditions (μ = 0.4) at a constant velocity of 20 m/s is examined. The Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) approach demonstrates superior tracking accuracy, closely following the reference trajectory with minimal lateral deviation, even during demanding maneuvers. In comparison, the conventional Model Predictive Control (MPC) shows satisfactory performance but has a slight offset during transient events, especially at peak lateral displacement points. The Linear Quadratic Regulator (LQR) performs the worst among the three controllers, showing significant deviations from the reference and a lag during dynamic changes. These results highlight the robustness and adaptability of the AMPC strategy in low-traction conditions, outperforming both MPC and LQR in maintaining lateral path accuracy. Additionally, as illustrated in Fig. 6(B), under the same low-μ conditions, the AMPC controller achieves the closest match with the reference signal, particularly during the dynamic interval between 6 and 12 s, effectively capturing transient peaks and troughs with minimal overshoot and phase delay. This level of precision is essential for maintaining directional stability and vehicle orientation accuracy. While MPC closely approximates the reference trajectory, it displays noticeable overshoot and phase lag during rapid transitions. LQR, on the other hand, shows a subdued response, significantly dampened and delayed, indicating limited ability to respond to dynamic yaw rate changes under low-friction conditions. These findings suggest that LQR lacks the responsiveness needed in such scenarios, whereas AMPC dynamically adjusts its control policy to adapt to changing traction conditions. Further, as demonstrated in Fig. 6(C), the yaw angle tracking among the controllers shows that the AMPC controller maintains near-perfect alignment with the reference, especially during abrupt transitions observed between 6 and 12 s. MPC also performs well but with slightly increased oscillations, while maintaining temporal alignment. LQR again displays the least effective performance, with notable deviations from the reference during deceleration phases, emphasizing its reduced ability to manage nonlinear dynamics under low-μ conditions. The superior yaw angle tracking performance of AMPC underscores its capacity to stabilize vehicle heading during maneuvers with limited surface grip, an essential aspect of safe and reliable vehicle control.

Also, Fig. 6(D) shows the steering control inputs generated by each controller. AMPC produces dynamic yet smooth steering commands that match its high tracking accuracy. Although these inputs are more aggressive, they stay within feasible operational limits, indicating a well-regulated control authority. MPC provides moderately dynamic inputs, balancing responsiveness and smoothness. In contrast, LQR uses conservative steering actions, which seem insufficient to compensate for traction loss. These control inputs support the earlier observations: AMPC not only achieves superior tracking performance but does so with properly modulated control efforts, emphasizing its robustness and real-time adaptability under degraded traction conditions.

In summary, the comparative analysis across lateral position, yaw rate, yaw angle, and steering inputs demonstrates the superior performance of the AMPC approach in low-friction driving conditions. AMPC consistently outperforms both MPC and LQR in tracking accuracy and dynamic response, maintaining vehicle stability and control even during aggressive maneuvers. These findings affirm the effectiveness of adaptive predictive control strategies in enhancing vehicle safety and handling under adverse road conditions.

The observed advantages of AMPC come from its ability to adapt in real-time to changes in vehicle dynamics and road surface conditions, which traditional controllers like MPC and LQR lack. Unlike fixed-gain methods, AMPC updates its internal model and constraints to handle nonlinearities and variations in traction, leading to better responsiveness and control accuracy. While MPC is still a solid baseline, its performance is limited under rapidly changing conditions because of its fixed model assumptions. LQR, though computationally efficient, struggles to maintain tracking when traction is reduced due to its linear structure and lack of predictive capabilities. Overall, these findings support the increasing need for adaptive, model-based control strategies in autonomous and advanced driver-assistance systems, especially in situations with uncertain or degraded environmental conditions.

Vehicle responses under speed variation with crosswind disturbances

The proposed Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework was rigorously evaluated under a compound scenario involving dynamically adverse driving conditions, including rapidly varying speed profiles, lateral crosswind disturbances, and a reduced tire-road friction coefficient (μ = 0.4), representing slippery environments such as wet or icy roads. These operational conditions introduce substantial nonlinearities and parametric uncertainties, significantly challenging the effectiveness of traditional control approaches. Within this context, the evaluation aimed to determine the AMPC system’s ability to maintain trajectory adherence, particularly in terms of lateral displacement and yaw dynamics, under continuously evolving disturbances and degraded traction conditions.

Over a 20-s simulation window, the lateral tracking performance of the AMPC-controlled vehicle was compared to a predefined reference trajectory. As shown in Fig. 7(A), the reference lateral motion exhibits a pronounced displacement, peaking at approximately 5.4 m near the 6.5-s mark. The AMPC-controlled response tracks this reference closely, although with a slightly attenuated peak of around 4.7 m. This deliberate reduction in amplitude reflects the controller’s conservative response strategy, balancing performance with safety by limiting excessive lateral force generation on low-friction surfaces. During the highly dynamic interval between 4 and 10 s, the controller exhibits a mild lag and understeer behavior, though it successfully maintains trajectory coherence. Beyond this interval, both the reference and the AMPC outputs converge toward zero displacement, highlighting the system’s ability to reestablish path conformity without inducing oscillations or overshoot an indicator of high damping efficacy and closed-loop stability.

The corresponding lateral position error, shown in Fig. 7(B), provides further insight into the tracking performance. The error remains negligible during the initial phase, then peaks at + 0.12 m around 6 s, coinciding with the maximum reference deviation as observed. A notable negative error trough of –0.18 m appears at approximately 9.5 s, representing the controller’s assertive correction during the realignment phase. This overshoot, although significant, is quickly damped out, and the error diminishes below ± 0.05 m by 12 s, stabilizing near zero. The error profile’s smooth, oscillation-free decay validates the AMPC’s robust stabilizing characteristics and precise correction capabilities under time-varying disturbances.

Further evaluation of yaw dynamics supports these findings. As illustrated in Fig. 7(C), the reference yaw angle reaches a peak of 0.37 radians at around 6 s, while the AMPC-controlled yaw angle reaches a moderate maximum of 0.23 radians, revealing the controller’s stability-prioritized behavior during aggressive maneuvering. At approximately 8 s, the AMPC initiates a corrective action, dipping to –0.45 radians, illustrating its capacity to maintain directional control under sharp changes in yaw demand and reduced traction. As the system evolves, the yaw angle realigns with the reference, exhibiting reduced phase lag and lower-frequency oscillations, suggesting the controller’s ability to adjust adaptively to nonlinear internal dynamics and external aerodynamic disturbances.

Quantitative analysis of yaw tracking error reveals a peak value of 0.275 radians at approximately 6 s, which corresponds with the period of compounded crosswind and velocity fluctuations, as depicted in Fig. 7(D). The error curve exhibits damped oscillations, stabilizing near 0.09 radians after 10 s. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of yaw angle tracking, calculated as 0.118 using Eq. (38), and the maximum absolute yaw error of 0.275 radians based on Eq. (39), collectively confirm the controller’s precision in maintaining low residual error even in severely degraded conditions. These metrics underscore the AMPC’s robustness in simultaneously managing large state variations and external disruptions without performance degradation.

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of yaw angle tracking:

where ri is the reference yaw angle and yi is the AMPC output.

Maximum Absolute Yaw Error:

Crucially, this high-fidelity tracking is achieved without resorting to aggressive or saturating control actions. Although steering actuation data is not visualized directly, the computed maximum steering rate remains well-contained at 0.48 radians per second, safely within the capacity of commercial electric power steering systems. This characteristic indicates a smooth control signal profile devoid of chattering, actuator saturation, or abrupt directional changes, all of which are vital for real-world deployment in safety–critical applications.

Supporting evidence is also drawn from the analysis of yaw rate and lateral acceleration responses. The AMPC-controlled yaw rate, shown in Fig. 7(E), tracks the reference with similar global trends while exhibiting lower amplitude excursions. At 8 s, the reference yaw rate drops sharply to –0.37 rad/s, followed by a transition to a positive peak of approximately 0.35 rad/s at 10 s. The AMPC’s corresponding values are damped, ranging between –0.25 rad/s and slightly below the reference peak, representing an adaptive suppression of sharp yaw dynamics to preserve lateral stability. The convergence of both responses post-12 s confirms the controller’s ability to maintain equilibrium despite dynamic inputs.

Lateral acceleration data, as presented in Fig. 7(F), further corroborate the system’s stability and responsiveness. Within the 0–6 s range, acceleration remains within ± 1 m/s2, indicating smooth directional changes. A peak of approximately 4 m/s2 is observed at 10 s, associated with a high-load maneuver. The AMPC maintains a symmetric rise and decay around this peak without excessive overshoot, and the residual oscillations quickly attenuate to within ± 1.2 m/s2. This balance between responsiveness and restraint ensures both passenger comfort and chassis safety by avoiding sustained lateral forces or rapid jerks.

Overall, the simulation results and analytical metrics jointly confirm that the proposed AMPC framework delivers a high degree of lateral motion accuracy and vehicle stability under dynamically uncertain and safety–critical conditions. The controller’s conservative yet responsive steering actions ensure that lateral displacement, yaw angle, and associated errors remain within acceptable bounds while avoiding actuator overuse and chattering. The ability to regulate tracking precision within physical constraints, coupled with its robustness to disturbances, positions the AMPC as a highly viable candidate for next-generation semi-autonomous vehicle control systems, especially in environments characterized by low friction and rapidly varying external influences.

To validate the proposed Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework, a comprehensive simulation-based evaluation was conducted across diverse operating conditions, including nominal, low-friction, and disturbance-rich environments. The AMPC’s performance was benchmarked against conventional MPC and LQR controllers using key metrics such as lateral tracking error, yaw angle deviation, and control effort. Quantitative measures, including RMSE and peak error, demonstrated that AMPC consistently outperformed traditional methods, maintaining stability and accuracy even under rapid parameter variation and delayed driver intervention. A human-in-the-loop simulation further confirmed the controller’s robustness in managing shared control scenarios, bridging the gap between automated and manual operation. These results validate the AMPC’s capability for real-time, safe lateral control in semi-autonomous vehicles.

Conclusion

This study presented an Adaptive Model Predictive Control (AMPC) framework for lateral motion tracking in semi-autonomous vehicles, addressing the performance limitations of conventional controllers under nonlinear and time-varying conditions. Unlike standard MPC and LQR approaches that rely on fixed-parameter models, the proposed AMPC continuously updates its internal prediction model using recursive least squares estimation of real-time vehicle parameters such as mass and tire–road friction. This self-learning capability allows the controller to adapt dynamically to environmental and operational variations, maintaining high tracking precision and vehicle stability even under aggressive maneuvers, low-traction surfaces, and external disturbances. Through this adaptive modeling approach, AMPC bridges the gap between robustness and responsiveness, key requirements for reliable autonomous and shared-control driving systems.

Simulation results obtained from high-fidelity MATLAB/Simulink experiments confirmed the superior performance of the AMPC over conventional MPC. The controller reduced lateral tracking error by up to 43% and yaw angle RMSE by 37% under degraded traction conditions while maintaining maximum yaw error below 0.275 radians. Steering control signals were smooth, non-saturating, and within actuator limits, with maximum steering rate constrained to 0.48 radians per second. These outcomes demonstrate that the AMPC effectively balances stability, precision, and actuator feasibility, ensuring safe operation across diverse driving scenarios. Its robustness was further validated through human-in-the-loop simulations, where it maintained lateral control during delayed driver interventions, highlighting its potential for cooperative human–machine control architectures.

Overall, the proposed AMPC framework offers an adaptive, computationally efficient, and scalable solution for lateral control in semi-autonomous vehicles. Future research should extend its implementation to embedded platforms, assess robustness under sensor and actuator imperfections, and expand the model to three-dimensional vehicle dynamics for real-world deployment.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author (K.Y., email: kumynnh2023@gmail.com.

Abbreviations

- Vehicle mass, m:

-

Total mass of the vehicle (kg)

- Vehicle speed, vx:

-

Longitudinal velocity of the vehicle (m/s)

- Lateral velocity, vy:

-

Lateral velocity of the vehicle (m/s)

- Yaw angle:

-

Rotation of the vehicle about the vertical axis (rad)

- Yaw rate, ψ˙:

-

Rate of change of yaw angle (rad/s)

- Front cornering stiffness, Cf:

-

Tire stiffness at the front axle (N/rad)

- Rear cornering stiffness, Cr:

-

Tire stiffness at the rear axle (N/rad)

- Front axle distance, lf:

-

Distance from CoG to front axle (m)

- Rear axle distance, lr:

-

Distance from CoG to rear axle (m)

- Yaw moment of inertia, Iz:

-

Rotational inertia of the vehicle about the vertical axis (kg·m2)

- Friction coefficient, μ:

-

Tire-road friction coefficient (–)

- Steering angle, δf:

-

Front wheel steering input (rad)

- External lateral force, Fw:

-

Lateral wind or disturbance force (N)

- External moment, Mw:

-

Moment due to external disturbances (N·m)

- Control moment, Mδ:

-

The moment generated by the control system (N·m)

- Prediction horizon, Np:

-

Number of steps over which future states are predicted (–)

- Control horizon, Nc:

-

Number of control inputs optimized in each MPC iteration (–)

- Weight matrix (state), Q:

-

Penalizes tracking error in the cost function (–)

- Weight matrix (input), R:

-

Penalizes control effort in the cost function (–)

References

Dang, D., Gao, F. & Hu, Q. Motion Planning for Autonomous Vehicles Considering Longitudinal and Lateral Dynamics Coupling. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10093180 (2020).

Yu, J., Pei, X., Guo, X., Lin, J. G. & Zhu, M. Path tracking framework synthesizing robust model predictive control and stability control for autonomous vehicle. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 234(9), 2330–2341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954407020914666 (2020).

Weiskircher, T., Wang, Q. & Ayalew, B. Predictive Guidance and Control Framework for (Semi-)Autonomous Vehicles in Public Traffic. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 25(6), 2034–2046. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCST.2016.2642164 (2017).

Rokonuzzaman, M., Mohajer, N., Nahavandi, S. & Mohamed, S. Model Predictive Control With Learned Vehicle Dynamics for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking. IEEE Access 9, 128233–128249. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3112560 (2021).

Liang, Y. et al. A Novel Combined Decision and Control Scheme for Autonomous Vehicle in Structured Road Based on Adaptive Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23(9), 16083–16097. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2022.3147972 (2022).

Pauca, G.-S. & Caruntu, C.-F. MPC-Based Dynamic Velocity Adaptation in Nonlinear Vehicle Systems: A Real-World Case Study. Electronics https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13152913 (2024).

Gao, F., Han, Y., Li, S. E., Xu, S. & Dang, D. Accurate Pseudospectral Optimization of Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for High-Performance Motion Planning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 8(2), 1034–1045. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2022.3153633 (2023).

Ji, Y. et al. Optimal Path Tracking Control Based on Online Modeling for Autonomous Vehicle With Completely Unknown Parameters. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 24(12), 15207–15218. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2023.3306040 (2023).

Sharma, T. & He, Y. Design of a tracking controller for autonomous articulated heavy vehicles using a nonlinear model predictive control technique”. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-body Dyn. 238(2), 334–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/14644193241232353 (2024).

Shirazi, M. M. & Rad, A. B. ${{\mathcal L}_1}$ Adaptive Control of Vehicle Lateral Dynamics. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 3(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2017.2788186 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. A double-layered nonlinear model predictive control based control algorithm for local trajectory planning for automated trucks under uncertain road adhesion coefficient conditions. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 21(7), 1059–1073. https://doi.org/10.1631/FITEE.1900185 (2020).

Song, X., Shao, Y. & Qu, Z. A Vehicle Trajectory Tracking Method With a Time-Varying Model Based on the Model Predictive Control. IEEE Access 8, 16573–16583. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2963291 (2020).

Domina, Á. & Tihanyi, V. Model Predictive Controller Approach for Automated Vehicle’s Path Tracking. Sensors https://doi.org/10.3390/s23156862 (2023).

Mata, S., Zubizarreta, A. & Pinto, C. Robust Tube-Based Model Predictive Control for Lateral Path Tracking. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 4(4), 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2019.2938102 (2019).

Cheng, J., Zhang, B., Zhang, C., Zhang, Y. & Shen, G. A model-free adaptive predictive path-tracking controller with PID terms for tractors. Biosyst. Eng. 242, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2024.04.009 (2024).

Choi, W. Y., Lee, S.-H. & Chung, C. C. Horizonwise Model-Predictive Control With Application to Autonomous Driving Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 18(10), 6940–6949. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2021.3137169 (2022).

Huang, Y. et al. A Novel Local Motion Planning Framework for Autonomous Vehicles Based on Resistance Network and Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 69(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2019.2945934 (2020).

Weiskircher, T., Ayalew, B. Predictive trajectory guidance for (semi-)autonomous vehicles in public traffic,” in 2015 American Control Conference (ACC), 3328–3333. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACC.2015.7171846. (2015)

Gao, Y., Gray, A., Tseng, H. E. & Borrelli, F. A tube-based robust nonlinear predictive control approach to semiautonomous ground vehicles. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 52(6), 802–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114.2014.902537 (2014).

Wu, Y., Li, S., Zhang, Q., Sun-Woo, K. & Yan, L. Route Planning and Tracking Control of an Intelligent Automatic Unmanned Transportation System Based on Dynamic Nonlinear Model Predictive Control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23(9), 16576–16589. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2022.3141214 (2022).

Yao, Q. & Tian, Y. A Model Predictive Controller with Longitudinal Speed Compensation for Autonomous Vehicle Path Tracking. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9224739 (2019).

Chen, S., Chen, H., Pletta, A., Negrut, D. Coupled Lateral and Longitudinal Control for Trajectory Tracking, Lateral Stability, and Rollover Prevention of High-Speed Automated Vehicles Using Minimum-Time Model Predictive Control,” https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2021-68099(2021).

Biswas, A. et al. State-of-the-Art Review on Recent Advancements on Lateral Control of Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Access 10, 114759–114786. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3217213 (2022).

Capallera, M., Angelini, L., Meteier, Q., Khaled, O. A. & Mugellini, E. Human-Vehicle Interaction to Support Driver’s Situation Awareness in Automated Vehicles: A Systematic Review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 8(3), 2551–2567. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIV.2022.3200826 (2023).

Jiménez, F. B. T.-I. V. Ed., “Chapter 9 - Human Factors,” Butterworth-Heinemann, 345–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812800-8.00009-6. (2018)

Zhao, Y., Lv, C., Yang, L. Chapter eleven - Intelligent haptic interface design for human–machine interaction in automated vehicles,” Y. Zhao, C. Lv, and L. B. T.-H.-M. I. for A. V. Yang, Eds., Academic Press, 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-443-18997-5.00002-1 (2023).

Huang, C., Lv, C., Hang, P., Hu, Z. & Xing, Y. Human–Machine Adaptive Shared Control for Safe Driving Under Automation Degradation. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 14(2), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1109/MITS.2021.3065382 (2022).

Mandujano-Granillo, J. A. et al. Human–Machine Interfaces: A Review for Autonomous Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 12, 121635–121658. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3450439 (2024).

Eskandarian, A. Scanning the Issue. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23(9), 13920–13953. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2022.3199627 (2022).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kumlachew Yeneneh: Conceptualization, methodology, simulation modeling, software implementation, data analysis, visualization, and original draft preparation. Bisrat Yoseph: Supervision, guidance on control system design, critical revision of the manuscript, and validation of results, Literature review, data curation, result interpretation. Gadisa Sufe: Literature review, data curation, result interpretation, and manuscript editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yeneneh, K., Yoseph, B. & Sufe, G. Adaptive model predictive control for robust lateral motion tracking of semi-autonomous vehicles with dynamic parameter variation. Sci Rep 16, 716 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30352-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30352-3