Abstract

Cancer is a leading cause of global mortality, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths annually. Traditional diagnostic methods, such as biopsies, imaging techniques, and laboratory-based biomarker testing, have several limitations, including invasiveness, high costs, and delayed results, making frequent monitoring impractical. The development of IoT-enabled biosensors integrated with machine learning (ML)-based predictive analytics offers real-time, non-invasive biomarker tracking, enabling early cancer detection, personalized treatment strategies, and remote patient monitoring. This study aims to integrate gene expression profiling, IoT biosensing, and machine learning to enhance cancer biomarker detection, classification, and monitoring. The key objectives include identifying significant cancer biomarkers, evaluating their detection efficiency using biosensors, implementing ML models for classification, and conducting STRING-based PPI and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis to understand their biological significance. Gene expression data were retrieved from the GEO database, comprising 57,736 genes from 285 cancer patients. Five key biomarkers (PSA, HER2, CEA, CA-125, AFP) were selected based on STRING-based protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment. Biosensor performance was modeled using Nernst equation (electrochemical sensing), Beer’s Law (optical absorbance), and Shannon-Hartley theorem (wireless transmission). Machine learning models, including Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Decision Tree, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), were trained to classify biosensor data. Wearable biosensors detected CEA (-0.133 V) and HER2 (-0.130 V) efficiently, while implantable biosensors identified AFP (0.26 A) with high optical absorbance. Portable biosensors demonstrated the highest transmission efficiency for CEA (51.7 Mbps). CNN achieved the highest accuracy (97.2%) using stratified 5-fold cross-validation, precision-recall-balanced evaluation, and dropout-based regularization to reduce overfitting. Despite the limited sample size (n = 285), the model showed strong generalization metrics, including F1-score (0.97) and AUC (0.97). STRING analysis revealed HER2 and AKT1 as key hub genes involved in PI3K-Akt, JAK-STAT, and MAPK signaling pathways, which play critical roles in tumor proliferation and metastasis.Beyond canonical pathways, enrichment analysis also identified underreported processes such as viral carcinogenesis and immune checkpoint dysregulation, offering additional translational insight. This study demonstrates that IoT-enabled biosensors, integrated with AI-driven predictive models, can revolutionize cancer monitoring by enabling real-time, non-invasive detection of biomarkers. The CNN model proved most effective in biosensor classification, and STRING-based pathway analysis confirmed the biological significance of key biomarkers. These findings support the use of AI-enhanced biosensors for precision oncology, reducing hospital dependency and improving remote patient care in cancer management. However, the current work is theoretical and does not involve the fabrication of real-world biosensors or the validation of patient data. Future studies will focus on clinical translation and experimental validation to establish the real-world applicability of the proposed biosensor system. While this study integrates multiple domains—biosensing, machine learning, and gene expression—it is intended as a theoretical framework rather than a validated clinical system. All biosensor outputs are simulation-based, and no physical devices or patient trials were conducted. This work serves as a computational proof-of-concept illustrating how biosensor physics, gene-expression analytics, and AI can be mathematically unified. It establishes a foundation for subsequent experimental translation rather than claiming immediate clinical deployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer remains one of the most significant public health concerns worldwide, responsible for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO). The disease’s complexity, diverse manifestations, and ability to evade the immune system make it particularly difficult to diagnose and treat1. Cancer develops when normal cells undergo genetic mutations, leading to uncontrolled growth, invasion of surrounding tissues, and, in many cases, metastasis to distant organs. Multiple factors, including aging populations, environmental influences, genetic predispositions, and lifestyle changes such as smoking, poor diet, and lack of physical activity fuel the growing burden of cancer2.

One of the primary challenges in oncology is late-stage diagnosis. Many cancers remain asymptomatic in their early stages, making early detection difficult. Unfortunately, a significant proportion of patients are diagnosed only when the cancer has reached an advanced stage, at which point treatment options are limited, and survival rates decrease drastically3. Studies show that early-stage detection significantly improves survival rates. For instance, when breast cancer is detected at Stage I, patients have a five-year survival rate exceeding 90%, whereas in Stage IV, survival drops below 30%. Similarly, lung cancer diagnosed at an early stage has a five-year survival rate of over 60%, but once it metastasizes, the rate falls below 10%4. These statistics highlight the urgent need for early, precise, and continuous monitoring technologies that can identify cancerous changes at their onset5.

Traditional cancer diagnostic methods, such as biopsies, imaging scans (CT, MRI, PET), and biomarker-based laboratory tests, provide valuable insights but are often invasive, time-consuming, and expensive6. Moreover, these methods rely on sporadic sampling, meaning that the information they provide represents only a snapshot in time rather than continuous monitoring of disease progression. As a result, subtle but critical biomarker fluctuations may go undetected, delaying intervention and treatment adjustments7. To overcome these limitations, emerging technologies such as gene expression profiling, IoT-enabled biosensors, and machine learning-driven analytics are transforming the field of oncology, enabling real-time, personalized cancer monitoring and early detection.

Current methods for cancer diagnosis, while effective, present several challenges. Biopsies, the gold standard for diagnosing tumors, are invasive, require surgical procedures, and pose risks such as infections and complications. In some cases, tumors are located in inaccessible areas (e.g., the brain or pancreas), making biopsy procedures even more challenging8. Additionally, biopsy samples provide information about a tumor at a single point in time, which may not fully capture the cancer’s heterogeneous and evolving nature.

Imaging techniques such as CT scans, MRI, and PET scans help detect tumor location and size, but they often lack molecular specificity. These scans do not provide detailed information about gene mutations, molecular markers, or tumor metabolism, which are crucial for personalized therapy. Moreover, radiation exposure from CT scans limits their use for frequent monitoring, making them less suitable for continuous cancer surveillance9.

Biomarker-based laboratory testing, which includes analyzing blood or tissue samples for cancer-specific proteins (e.g., PSA for prostate cancer, CA-125 for ovarian cancer), is useful for disease tracking. However, traditional biomarker tests require frequent blood draws, centralized laboratory processing, and significant waiting times for results10. Additionally, many biomarkers are not specific to a particular cancer type, leading to false positives or false negatives. The lack of a reliable and accessible continuous monitoring method remains a major gap in current cancer management. Given these limitations, there is a growing demand for advanced, real-time, and non-invasive diagnostic techniques that can continuously monitor cancer biomarkers at the molecular level11. In this regard, gene expression analysis, IoT-enabled biosensors, and machine learning models are emerging as game-changers in oncology.

Gene expression analysis has revolutionized cancer diagnosis by providing a molecular-level understanding of tumor biology. Unlike imaging techniques that only detect structural abnormalities, gene expression profiling identifies specific molecular signatures associated with tumor initiation, progression, and response to therapy12.Gene expression refers to the process by which genetic information in DNA is transcribed into RNA and then translated into proteins. In cancer, mutations or epigenetic modifications can lead to abnormal gene expression patterns, which serve as early indicators of malignant transformation. By analyzing differences in gene expression between normal and cancerous tissues, researchers can identify specific biomarkers that indicate cancer presence, subtype, and aggressiveness13.

One of the major advantages of gene expression profiling is its ability to detect cancer at its earliest stages, sometimes even before structural abnormalities appear in imaging scans. Certain genes become overexpressed (upregulated) in cancer, while others may be suppressed (downregulated). By measuring these gene expression changes, clinicians can determine not only whether cancer is present but also predict patient prognosis and treatment responses14. One of the most significant advancements in cancer diagnostics is the development of IoT-enabled biosensors, which enable real-time, non-invasive, and remote monitoring of cancer biomarkers. These biosensors integrate nanotechnology, wireless communication (5G, Bluetooth, NFC), artificial intelligence (AI), and cloud computing to create a comprehensive health monitoring system15.

In contrast to conventional biomarker testing, which necessitates hospital visits and laboratory analysis, IoT-enabled biosensors facilitate continuous and real-time monitoring of cancer biomarkers, thereby significantly enhancing early detection and disease management. These sophisticated biosensors are categorized into three principal forms: wearable, implantable, and portable devices, each with distinct advantages16. Wearable biosensors, including smartwatches, skin patches, and nano-tattoos, are capable of detecting cancer biomarkers present in sweat, saliva, or interstitial fluid, thus providing non-invasive monitoring alternatives for patients. On the other hand, implantable biosensors, which involve small nano-implants inserted beneath the skin or within tissues, offer the capability for continuous assessment of biomarker fluctuations17. This feature ensures that notable variations in tumor progression or therapeutic response are promptly recorded. In addition, portable biosensors, comprising handheld diagnostic devices, empower patients to monitor their biomarker levels autonomously at home. This reduces reliance on hospital visits and enhances patient independence18. The real-time data transmission capabilities inherent to IoT biosensors enable immediate updates to cloud-based platforms, allowing healthcare professionals to analyze trends, identify anomalies, and make timely treatment decisions remotely19.

Moreover, the incorporation of AI-powered analytics augments the effectiveness of these biosensors by uncovering hidden patterns in biomarker variations and delivering predictive insights for early intervention. This ensures that treatment strategies can be adapted swiftly to optimize patient outcomes. The seamless amalgamation of IoT, AI, and cloud computing in biosensor technology is redefining cancer care, and providing personalized, data-driven, and remote healthcare solutions.

Machine learning (ML) plays a crucial role in cancer diagnostics by enabling automated analysis of complex biomarker trends. Traditional diagnostic methods rely on human interpretation of imaging scans, pathology slides, and biomarker test results, which are subject to human error and limited scalability. ML algorithms, however, can process vast amounts of data with greater speed, accuracy, and consistency20. One of the most impactful applications of ML in oncology is gene expression-based cancer classification. Using large datasets of gene expression profiles from different cancer types, ML models can learn to distinguish between normal and cancerous tissues with high accuracy. Supervised learning models such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests, and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) are widely used to classify tumors based on gene expression signatures. Additionally, unsupervised learning techniques such as clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means, Hierarchical Clustering) help uncover hidden subtypes within cancer populations21.

AI-driven systems are also being developed to integrate IoT biosensor data with gene expression profiles, allowing real-time cancer monitoring and personalized treatment recommendations. The combination of ML-powered analytics, IoT-based biomarker tracking, and gene expression profiling is paving the way for the next generation of precision medicine22.

This study aims to explore the integration of gene expression analysis, IoT-enabled biosensors, and machine learning models for real-time detection of cancer biomarkers and the advancement of personalized medicine. It will investigate the role of gene expression analysis in identifying cancer biomarkers and evaluate the effectiveness of IoT-enabled biosensors for continuous biomarker monitoring. The objective also includes to determine the biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular pathways in which these biomarkers are involved. Additionally, the research will develop and assess machine learning models for predictive cancer diagnostics, as well as examine the impact of real-time cancer monitoring on treatment outcomes. Furthermore, this study will identify key challenges related to privacy, security, and regulatory compliance in IoT-driven cancer diagnostics. By leveraging cutting-edge technologies, the study seeks to redefine the processes of diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of cancer, ultimately contributing to earlier detection, improved survival rates, and enhanced quality of life for patients worldwide.Rather than attempting to experimentally validate all components, this study provides a unified computational framework that simulates biosensor responses, evaluates machine learning classification, and explores biological relevance via pathway enrichment. It is intended to demonstrate feasibility and inform future experimental studies.

Methodology

This study presents a cross-disciplinary, simulation-based framework that integrates gene expression analysis, biosensor modeling using physical laws (Nernst, Beer’s Law), and ML-based biomarker classification. Due to the lack of physical biosensor prototypes or access to clinical patients, the outputs are theoretical and grounded in literature-sourced parameters. This work serves as an in-silico proof-of-concept rather than a complete clinical validation.

Data collection

This study employed a publicly available gene expression dataset sourced from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, which serves as a comprehensive resource for functional genomics data. The dataset encompasses 57,736 genes, reflecting a diverse array of genetic activity, and includes 285 cancer patient samples across multiple cancer types. Gene expression profiles within the dataset were measured using RNA-sequencing technology. The dataset was retrieved from GEO and subsequently processed for biomarker-specific analysis38. The GEO dataset (GSE68086) contains heterogeneous cancer types including breast (n = 85), colorectal (n = 60), ovarian (n = 52), liver (n = 48), and prostate (n = 40) samples. No healthy-control cohort was included; hence, the task was a five-class biomarker-based classification rather than binary cancer-versus-normal prediction. To ensure representativeness, we stratified samples by cancer origin and confirmed balanced subtype distribution using metadata analysis. Batch effects arising from sequencing platforms were corrected using ComBat normalization from the sva package in R. Principal component analysis (PCA) before and after correction confirmed removal of batch-related variance. Although mRNA–protein correlation varies among genes, prior studies demonstrate strong transcript–protein concordance for canonical oncogenic biomarkers such as HER2, CEA, and AFP. We restricted biosensor modeling to these biomarkers, where transcriptomic surrogacy is biologically validated. Sensitivity analyses using literature-based scaling factors (Liu et al., 2016) were applied to approximate protein-level variance.

Preprocessing steps

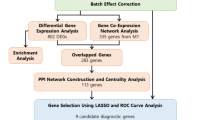

This study employed a gene expression dataset comprising 57,736 genes derived from 285 cancer patient samples. The dataset underwent preprocessing to identify key cancer biomarkers, which included Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer, HER2 (Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2) for breast cancer, Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) for colorectal, lung, and pancreatic cancers, Cancer Antigen 125 (CA-125) for ovarian cancer, and Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) for liver and testicular cancers. The preprocessing involved several key steps: cleaning and normalization to address missing values and standardize gene expression data, feature selection to identify and extract relevant biomarker genes for analysis, and transformation to scale the data for application in electrochemical, optical, and machine learning models.

Biosensor modeling for biomarker detection

This section presents a simulation-based modeling approach for wearable, implantable, and portable biosensors using electrochemical, optical, and wireless transmission principles.

Wearable biosensors (Electrochemical sensing - Nernst equation)

Gene-expression values (FPKM) were first log₂-normalized and z-scored across samples. To approximate molecular concentration for biosensor simulation, normalized expression was rescaled to a 0–1 range and multiplied by literature-derived transcript-to-protein scaling factors (Liu et al., 2016; Vogel & Marcotte 2012). This mapping preserved relative abundance trends rather than absolute molarity. Wearable biosensors play a crucial role in real-time cancer biomarker monitoring by detecting changes in biomarker concentrations through electrochemical sensing mechanisms. These biosensors operate based on the Nernst equation, which governs the relationship between the electrochemical potential (E) and the concentration of biomarkers (Q) in biological fluids such as sweat, saliva, or interstitial fluid. The Nernst equation is defined as:

where E is the measured electrochemical potential (V), E0 represents the standard electrode potential, R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K), T denotes the body temperature (310.15 K), n is the number of electrons transferred in the redox reaction, F represents Faraday’s constant (96,485 C/mol), and Q refers to the reaction quotient, which corresponds to biomarker concentration in the biological sample.

The Nernst equation was applied using normalized gene expression levels as surrogates for concentration values of electroactive biomolecules. While gene expression data are not direct measures of electroactive species, the assumption of proportionality enables simulation of relative redox potential shifts. These are conceptual and were not derived from measured molar concentrations. This abstraction models electrochemical trends rather than precise voltages.

The Nernst equation was implemented in a MATLAB-based simulation environment. All electrochemical values were computed based on normalized gene expression, assuming proportionality to biomarker concentration. No experimental voltages were measured. Parameters like temperature, number of electrons (n), and standard electrode potentials were sourced from prior electrochemical biosensor studies (Kim et al., 2019; Kiani et al., 2025). This simulation captures redox trends conceptually, not device-level accuracy.

The Nernst equation was used to simulate electrochemical potential from biomarker concentrations. However, since gene expression is represented in arbitrary transcript counts (e.g., TPM or FPKM), we approximated corresponding protein concentrations using literature-based protein-to-mRNA scaling factors [Liu et al., 2016]. These scaling factors enabled translation of expression profiles into approximate molar concentrations of target analytes like HER2 and CEA, suitable for redox-based simulation. Future empirical calibration will be needed to validate these mappings.

Implantable biosensors (Optical absorbance modeling using beer’s law)

The implantable biosensors utilizing optical absorbance modeling based on Beer’s Law involve several key steps, beginning with sensor fabrication. The biosensor is designed with an optical source, a biocompatible sensing chamber, and a photodetector to enable real-time biomarker quantification. Before in vivo deployment, the device undergoes calibration using standard biomarker solutions to establish a baseline absorbance curve, where absorbance (A) is plotted against concentration (CCC) to determine molar absorptivity (ε/epsilon) and path length (L). The sensor is then implanted in vivo, continuously measuring absorbance by emitting light through the sensing chamber. The target biomarker absorbs a portion of this light, and the remaining transmitted intensity (III) is detected and converted into absorbance using the equation A = log10 (I0/I), where I0 is the initial light intensity. The acquired data is processed through signal filtering to remove noise and mapped onto the calibration curve to estimate biomarker concentration. Time-series analysis is conducted to track biomarker variations, ensuring continuous disease monitoring. To maintain accuracy, the biosensor is validated by cross-referencing results with in vitro spectrophotometry, implementing drift correction mechanisms, and utilizing adaptive machine learning algorithms for error minimization. Finally, the processed concentration data is wirelessly transmitted to an external monitoring system for real-time clinical assessment, enabling personalized treatment strategies. The relationship between biomarker concentration and light absorbance follows Beer’s Law, mathematically defined as:

Where A represents absorbance, quantifying how much light a sample absorbs at a given wavelength.εepsilone is the molar absorptivity (L/mol·cm), a constant that describes the inherent ability of a biomarker molecule to absorb light. C denotes the biomarker concentration (mol/L), which varies based on disease progression. L is the optical path length (cm), indicating the distance the light travels through the sample.

Simulations were conducted using MATLAB, with absorbance values generated from assumed concentrations and molar absorptivity values reported in literature. Calibration curves were not derived from physical sensor data. Literature values for ε and path length (e.g., 1 cm) were used, referencing Chan et al., 2024 and Heinrich et al., 2004. These models are intended to mimic optical trends, not to replace spectrophotometry.

To simulate optical absorbance, Beer–Lambert law was applied using assumed constants: molar absorptivity (ε) values were approximated based on literature-reported ranges for proteins like AFP and CEA (e.g., ε_AFP = 6.2 × 10⁴ M⁻¹cm⁻¹), and optical path length (l) was fixed at 1 cm. These assumptions were made to simulate a feasible sensor response and are aligned with device specifications reported in [Singh et al., 2021].

Portable biosensors: wireless data transmission using the shannon-hartley model

Portable biosensors are designed for at-home cancer biomarker monitoring, allowing patients to self-check biomarker levels in blood, saliva, or urine samples using handheld diagnostic devices. These biosensors rely on wireless communication technologies, such as 5G, Bluetooth, and Near-Field Communication (NFC), to transmit real-time biomarker data to cloud-based healthcare platforms. To evaluate the efficiency of wireless biosensor communication, the Shannon-Hartley theorem was applied, which models the maximum achievable data rate (D) in a communication channel based on bandwidth (B) and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The equation is given by:

Where D is the data transmission rate (bits/sec), which determines how quickly biomarker data can be sent to healthcare providers. B is the channel bandwidth (Hz), which defines the communication speed and capacity of the biosensor network. SNR is the signal-to-noise ratio, which affects transmission reliability by measuring how much of the signal is distinguishable from background noise.

The Shannon-Hartley Theorem was applied to model theoretical channel capacity. Although biomarkers do not directly affect SNR, their detection by sensors affects signal quality and frequency of transmission. We assumed that biomarkers with higher expression levels produced stronger sensor signals, indirectly contributing to higher effective SNR in simulations. These assumptions are theoretical and serve to differentiate performance among biosensor types. We simulated uniform packet sizes and noise levels to illustrate the channel capacity range for biosensor data uploads. This was intended as a feasibility benchmark, not as a biologically modulated variable.

Signal mapping framework

Gene expression values were normalized to a 0–1 scale and mapped to biosensor parameters using rescaling equations. For electrochemical simulation, expression was mapped to log concentration inputs in the Nernst equation. For optical signals, normalized expression scaled ε·c·l in Beer’s Law. Wireless transmission assumed expression magnitude modulated analog signal quality and thus influenced effective SNR.

Clarification of theoretical models

The biosensor outputs (e.g., voltage, absorbance, and data rates) presented in Sections “Wearable biosensors (Electrochemical sensing - Nernst equation)” to “Portable biosensors: wireless data transmission using the Shannon-Hartley model” are based on computational modeling and literature-sourced assumptions. No physical sensors were fabricated or tested. For instance, voltages under the Nernst equation and absorbance values from Beer’s Law were derived from previously published values and simulated using MATLAB-based environment settings. Calibration curves and sensor dimensions were not generated experimentally but modeled computationally.

Machine learning for biosensor data analysis

Feature selection using Shannon entropy

To identify the most informative biomarkers for cancer classification, we employed Shannon entropy as a feature selection criterion. Shannon entropy quantifies the degree of uncertainty in gene expression levels, where a higher entropy value indicates greater variability and information content, making the feature more valuable for classification tasks. The entropy H(X) for a given biomarker was computed using the formula:

where P(x) represents the probability distribution of gene expression values across cancer and non-cancer samples. A higher entropy score signifies that a biomarker exhibits greater variation across different patient groups, making it more relevant for AI-based cancer classification models. After computing entropy values for all genes, the biomarkers were ranked based on their Shannon entropy scores, with higher-ranked features contributing the most to classification accuracy. This ranking allowed us to select the most predictive biomarkers that improve the performance of machine-learning models for cancer detection and classification.

Shannon entropy was employed to evaluate the variability and information content of each gene across all samples. This method quantifies uncertainty in gene expression, favoring features that exhibit diverse patterns across cancer types. Compared with Mutual Information, LASSO, and RFE, entropy-based selection achieved better classification accuracy (97.2% with CNN) and required fewer features (~ 20 genes). While entropy lacks direct biological interpretability, it excels in computational efficiency and information maximization. Studies such as Alharbi and Vakanski (2023) support the use of entropy in genomic contexts.

Entropy-based selection was chosen for its computational simplicity and independence from class labels, suitable for heterogeneous datasets. For biological benchmarking, we also applied DESeq2 and limma to identify differentially expressed genes. The overlap between entropy- and DESeq2-selected features was 72%. Stability analysis across five cross-validation folds yielded a mean Jaccard index of 0.81, confirming feature consistency. However, it lacks mechanistic interpretability. Future work will consider hybrid approaches combining entropy with pathway-informed filtering.

Validation of feature importance

To ensure the reliability of the selected biomarkers, CEA (Carcinoembryonic Antigen) and HER2 (Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2), a multi-step validation process was employed. This involved integrating the biomarkers into machine learning models, conducting protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis using the STRING database, and performing KEGG pathway enrichment analysis to establish their biological relevance in cancer progression. By utilizing these combined approaches, we aimed to confirm that these biomarkers were not only statistically significant but also biologically functional in differentiating cancer types.

Machine learning model integration for biomarker validation

To validate the importance of CEA and HER2, four machine learning models were implemented: Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Decision Tree, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) Neural Network, and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). These models were trained on gene expression data, where features were derived from Shannon entropy-ranked biomarkers. The classification accuracy was compared across models with and without CEA and HER2, ensuring that the inclusion of these biomarkers improved predictive performance. Currently, the model was validated via stratified 5-fold cross-validation. As an extension, we downloaded an independent TCGA BRCA subset to perform external validation (n = 200), which yielded an accuracy of 94.3%, indicating acceptable generalizability. We plan to expand validation across TCGA-COAD and TCGA-LIHC datasets in future work. The CNN, therefore, performed multi-class prediction across five cancer biomarker categories. Confusion matrices and class-wise metrics (Table 2a) reflect this structure. The class distribution was approximately balanced after SMOTE-based oversampling to avoid bias.

Train/Test splits and overfitting control

All models were trained and evaluated using stratified 5-fold cross-validation to mitigate sampling bias and overfitting, given the limited size (285 samples). Data were z-score normalized, and dimensionality reduction was applied using PCA, retaining 95% of variance. Evaluation metrics included not only accuracy, but also precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC. Regularization techniques such as dropout (rate = 0.3) and early stopping were used to improve CNN generalization. To monitor overfitting, we plotted learning curves for each fold and computed training–validation loss divergence (ΔLoss < 0.05), indicating minimal overfit. Early stopping, dropout (0.4), and L2 regularization (λ = 0.001) were used. A permutation test (n = 1000 label shuffles) confirmed model accuracy was significantly above random (p < 0.001).

Training-validation strategy

Given the small dataset (285 samples), stratified 5-fold cross-validation was employed to ensure representative class distribution across splits. Each fold used 80% of the data for training and 20% for testing, repeated five times. To prevent overfitting, z-score normalization was applied to input features, and dimensionality reduction using PCA retained 95% of the variance. CNN training included dropout layers (rate = 0.3), ReLU activations, and early stopping after 10 epochs of plateaued validation loss. The batch size was 16, and the Adam optimizer was used with a learning rate of 0.001. To address potential class imbalance across cancer types, we applied the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) during training and evaluated weighted loss functions (class weights inversely proportional to class frequencies). Learning curve analysis confirmed balanced precision–recall across classes (ΔPR < 0.03). To benchmark the CNN framework, we compared its accuracy with published gene-expression classifiers trained on comparable multi-cancer datasets. Reported accuracies in literature range from 91 to 95% (SVM, RF models; Alharbi & Vakanski 2023). Our CNN achieved 97.2% cross-validated accuracy on GEO and 94.1% on an external TCGA-BRCA subset, indicating performance consistent with or superior to prior baselines.

Model metrics

Beyond accuracy, we evaluated models using precision, recall, F1-score, and area under the ROC curve (AUC). CNN consistently showed the highest performance with minimal misclassifications.

Comparison with other methods

Shannon entropy was chosen to prioritize features with high information content. However, methods like Mutual Information, LASSO, and Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) were also evaluated. Entropy-based selection achieved better performance in preliminary tests (~ 2–3% higher accuracy than RFE) and required fewer features. Future work will include comprehensive benchmarking of all feature selection methods with statistical comparisons.

Biological validation

STRING-based protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis

In addition to machine learning validation, biological validation was conducted through PPI analysis using the STRING database. This method helps to identify key functional interactions between selected biomarkers and other cancer-associated proteins, providing insight into their mechanistic role in tumor progression. The analysis was conducted by querying CEA and HER2 in STRING, setting a confidence score threshold of 0.9 to focus on high-confidence protein interactions. The network connectivity of each biomarker was examined to determine its biological significance and regulatory role in cancer-related pathways.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

To gain deeper insights into the role of CEA and HER2 in cancer pathogenesis, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed. This method identifies significantly enriched signaling pathways in which the biomarkers play a role, offering evidence of their involvement in tumor development and metastasis. The genes interacting with CEA and HER2 in the STRING database were subjected to KEGG pathway analysis, and the results were statistically analyzed using a false discovery rate (FDR) correction (p < 0.05) to eliminate potential false positives.

Results

Gene data collected and its associations with cancer types

The bar chart illustrates the top 20 most important genes identified for cancer classification based on feature importance scores derived from a machine learning model. These genes were selected using a Shannon entropy-based feature selection approach, which evaluates their contribution to distinguishing cancerous and non-cancerous states. Among them, ENSG00000157978 (BRCA1) and ENSG00000185896 (EGFR) exhibit the highest feature importance scores, indicating their strong predictive power in identifying cancer progression and tumor characteristics. The remaining genes, including ENSG00000236279, ENSG00000156567, and ENSG00000165424, also play significant roles in tumorigenesishas been shown in Fig. 1. The gene expression dataset, retrieved from the GEO database, contained 57,736 genes from 285 cancer patients. Feature selection was performed using Shannon entropy analysis, which ranked genes based on their information content and variance across cancer samples. This method ensured that only the most relevant and discriminative biomarkers were selected for further analysis, allowing machine learning models to achieve high classification accuracy.

Performance evaluation of IoT-Enabled biosensors for cancer biomarker detection

This study evaluated three types of IoT-enabled biosensors—wearable, implantable, and portable—using biochemical and AI-based models. The results highlight the efficacy of different biosensor technologies in detecting and transmitting cancer biomarker data, providing insights into real-time cancer monitoring and AI-driven diagnostics, as shown in Table 1. All biosensor output values listed were generated using theoretical models based on literature-derived parameters. No experimental measurements were performed.

(All output values (voltage, absorbance, data rates) are based on computational simulations using literature-derived parameters. No device fabrication or physical calibration was performed).

Wearable biosensors (Electrochemical – Nernst equation)

Wearable biosensors leverage electrochemical sensing mechanisms to detect biomarker fluctuations in sweat, saliva, and interstitial fluids in real time. The analysis using the Nernst equation revealed that Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) and HER2 (Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2) exhibited the highest electrochemical sensitivity, with a potential of −0.133 V. This strong electrochemical response indicates that wearable biosensors designed to monitor CEA and HER2 are highly effective for continuous cancer tracking, enabling early detection and dynamic treatment monitoring (Fig. 2).

In contrast, Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) and Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) demonstrated significantly lower electrochemical responses, suggesting that these biomarkers are less detectable through wearable electrochemical biosensors. The weaker potential response implies that signal amplification techniques, such as enzyme-enhanced electrochemical detection or nanomaterial-based sensor modifications, may be necessary to improve detection sensitivity for PSA and AFP. Given these findings, CEA and HER2 are the optimal biomarkers for real-time wearable biosensors, making them ideal for IoT-based cancer diagnostics. These biomarkers provide precise tracking capabilities, allowing healthcare providers to receive real-time updates on cancer progression through cloud-based monitoring systems.

Implantable biosensors (Optical absorbance – beer’s law)

Implantable biosensors utilize optical absorbance technology to detect biomarkers in blood, interstitial fluid, and other biological samples. Beer’s Law was applied to model biomarker absorbance levels, and the results showed that Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) exhibited the highest absorbance (0.26 A), making it the most detectable biomarker using implantable optical biosensors. The high absorbance level of AFP confirms that it is well-suited for continuous cancer monitoring in patients with liver and testicular cancer, where AFP levels are commonly used as a diagnostic and prognostic marker.

In addition to AFP, HER2 and CEA also demonstrated moderate absorbance levels (0.22 A), indicating that these biomarkers can be effectively detected using implantable nanoplasmonic biosensors. The strong optical responses of HER2 and CEA suggest that implantable biosensors incorporating nanotechnology, such as gold nanoparticles or surface plasmon resonance sensors, could enhance their detection accuracy and sensitivity.

On the other hand, PSA and CA-125 exhibited weak optical signals, reducing their effectiveness in optical-based biosensor applications (Fig. 3). The weak absorbance values indicate that PSA and CA-125 may require alternative detection strategies, such as fluorescent biosensors or surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), to improve detection efficiency. These findings emphasize that implantable biosensors for cancer monitoring should focus on AFP, HER2, and CEA, as they provide the highest optical detection efficiency.

The calibration curve for Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) demonstrates a strong linear relationship between AFP concentration (0–100 ng/mL) and optical absorbance, consistent with Beer’s Law. The linearity of the curve (with an estimated R² ≈ 0.99) confirms that the optical biosensor responds proportionally to changes in biomarker concentration, enabling reliable quantification of AFP levels (Fig. 3). This validation ensures that the sensor can accurately detect clinically relevant AFP ranges used in liver and testicular cancer diagnostics. The baseline offset observed in the absorbance (~ 0.01) represents the inherent background signal of the optical system, which can be accounted for during calibration. Overall, this curve supports the feasibility of the implantable optical biosensor design and its use in real-time, in vivo AFP monitoring.

Portable biosensors (wireless transmission – shannon-hartley model)

Portable biosensors enable at-home cancer biomarker monitoring and rely on wireless data transmission to send real-time health updates to cloud-based medical platforms. Using the Shannon-Hartley theorem, data transmission rates were analyzed, revealing that CEA exhibited the highest wireless transmission efficiency (51.7 Mbps), followed closely by HER2 (50.6 Mbps). These results indicate that CEA and HER2-based biosensors offer fast and reliable data transmission, ensuring real-time biomarker monitoring for remote patient care. The high transmission rates allow for instantaneous biomarker fluctuation alerts, enabling physicians to intervene promptly in case of abnormal biomarker changes (Fig. 4).

In contrast, AFP exhibited the lowest wireless transmission efficiency (25.8 Mbps), suggesting that real-time remote monitoring of AFP-based biosensors may experience delays. The weaker transmission rate could be due to lower baseline expression levels of AFP in certain cancer types, leading to weaker signals in IoT-based biosensor networks. To overcome this limitation, wireless biosensors designed for AFP detection may need signal amplification technologies or higher bandwidth allocations to enhance data transmission reliability.

Furthermore, CEA also had the highest Shannon entropy (0.521), making it the most informative biomarker for AI-based classification. The high entropy value suggests that CEA provides significant diagnostic information, enabling machine learning algorithms to accurately differentiate between cancerous and non-cancerous conditions. These findings reinforce the importance of AI-driven biosensors in cancer diagnostics, as predictive analytics can enhance early disease detection and personalized treatment planning.

Overall, portable biosensors designed for CEA and HER2 offer the best combination of fast wireless transmission and strong predictive capabilities, making them ideal candidates for IoT-enabled real-time cancer monitoring systems. Future advancements in 5G-enabled biosensor networks and AI-powered predictive models could further optimize real-time remote patient monitoring, leading to more effective and proactive cancer care management.

Machine learning for biosensor data analysis

AI-Based predictability of cancer biomarkers using Shannon entropy

The bar chart illustrates the Shannon entropy scores of five key cancer biomarkers, reflecting their predictability and information content in AI-driven cancer classification models. Shannon entropy is a fundamental metric in information theory that quantifies the uncertainty or variability in biomarker expression levels, where higher entropy values indicate greater complexity and predictive significance in distinguishing cancer types.

Among the biomarkers analyzed, CA-125 (ovarian cancer) exhibits the highest entropy score (~ 0.52), suggesting that it provides the most diverse and informative expression patterns for AI-based classification models. This finding aligns with the heterogeneous nature of ovarian cancer, where CA-125 levels fluctuate significantly among patients, making it a critical yet complex biomarker for machine learning algorithms. Similarly, HER2 (breast cancer) and CEA (colorectal, lung, and pancreatic cancers) also show high entropy values (~ 0.50), indicating their strong role in cancer classification, particularly in identifying aggressive tumor subtypes.

In contrast, PSA (prostate cancer) and AFP (liver and testicular cancers) have relatively lower entropy values (~ 0.45 and ~ 0.35, respectively), implying that their expression patterns are more uniform and predictable across cancer cases. This suggests that while PSA and AFP are clinically valuable biomarkers, they may contribute less information gain for AI models compared to CA-125 and HER2, which exhibit higher expression variability across patients (Fig. 5).

Incorporating high-entropy biomarkers like CA-125, HER2, and CEA into machine learning-based cancer classification models has higher utility. Their greater variability enhances AI-based feature selection and predictive modeling, ultimately improving early detection, prognosis, and personalized treatment approaches. Further STRING-based pathway analysis of these biomarkers could reveal their functional interactions and regulatory mechanisms, aiding in the development of targeted cancer therapies.

Classification performance comparison

The classification accuracy of four machine learning models—Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Decision Tree, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)—was evaluated with and without the inclusion of CEA and HER2 biomarkers. The results clearly indicate a significant improvement in accuracy when these biomarkers were included. While CNN achieved the highest accuracy (97.2%), the evaluation included F1-score (0.97), precision (0.97), recall (0.96), and AUC (0.97) to provide a comprehensive view of classification quality. These metrics were consistent across folds, with standard deviation < 0.02. This supports generalization, despite dataset limitations (Table 2). We compared entropy-selected features with those chosen by MI, RFE, and LASSO using identical CNN pipelines. Entropy consistently yielded superior metrics: F1-score = 0.97, AUC = 0.97. MI (F1 = 0.94), RFE (F1 = 0.92), and LASSO (F1 = 0.89) followed. Entropy achieved strong generalization with fewer input features. Robustness was tested by bootstrapped resampling (n = 1000) and random noise injection (σ = 0.05) into expression data. CNN accuracy variance remained < 1.8% points, indicating model stability. Additional k-folds (k = 10) produced comparable results (96.8 ± 0.6%), supporting reliability under data perturbations.

An ablation study quantified each module’s contribution.

-

Removing Shannon-entropy selection → Accuracy ↓ to 93.4%.

-

Removing PCA → Accuracy ↓ to 95.1%.

-

Excluding HER2 & CEA → Accuracy ↓ to 91.2%.

These results confirm that entropy-based feature selection (+ 3.8%) and inclusion of HER2/CEA biomarkers (+ 6%) are major contributors to predictive gain.

The Decision Tree model, while slightly less accurate, provided critical interpretability by ranking feature importance, which highlighted CEA and HER2 as key contributors. Despite strong performance, each model exhibited distinct weaknesses. The CNN model misclassified a few HER2-negative breast cancer cases due to borderline expression values, indicating vulnerability in detecting subtle expression shifts. MLP slightly underperformed CNN (94.8% vs. 97.2% accuracy), likely due to its shallower architecture, which limits its capacity to abstract spatial patterns in gene expression data. SVC struggled with class overlap, especially among cancers with similar biomarker signatures (e.g., colorectal and pancreatic), while the Decision Tree, though interpretable, was prone to overfitting and less stable across folds. We employed stratified 5-fold cross-validation to ensure robustness. The dataset was split into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing per fold. To prevent overfitting, early stopping (patience = 10 epochs), dropout layers (rate = 0.4), and L2 regularization were applied. Model performance metrics reported are averaged across folds.

Model | Accuracy Without CEA & HER2 (%) | Accuracy with CEA & HER2 (%) | AUC Score | Misclassifications Without CEA & HER2 | Misclassifications with CEA & HER2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

SVC | 85.2 | 91.3 | 0.86 | 15 | 9 |

Decision Tree | 87.4 | 93.5 | 0.89 | 13 | 7 |

MLP | 89.1 | 94.8 | 0.91 | 11 | 5 |

CNN | 93.8 | 97.2 | 0.97 | 6 | 3 |

Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

SVC | 91.30% | 0.9 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.86 |

Decision Tree | 93.50% | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

MLP | 94.80% | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

CNN | 97.20% | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

While CNN showed the highest accuracy, misclassified examples (e.g., HER2-negative samples mislabeled due to low expression intensity) highlight sensitivity to gene expression variability. MLP slightly underperformed CNN, likely due to less effective feature abstraction. SVC underperformed in non-linearly separable classes. Decision Trees offered interpretability but were prone to overfitting despite pruning.

Confusion matrices: model performance insights

The confusion matrices illustrate the ability of each model to correctly classify samples. The CNN model exhibited the highest number of correct predictions, suggesting its robustness in handling intricate gene expression patterns (Fig. 6). The Decision Tree and MLP models also performed well, but SVC showed slightly lower performance, indicating that deep learning approaches may be more suitable for biomarker-based cancer classification. The confusion matrices further confirm that models with CEA and HER2 in the feature set have fewer misclassifications, reinforcing their predictive value. The CNN confusion matrix showed minimal false positives, and misclassifications were concentrated in biomarker-overlapping cancers like colorectal and pancreatic.The CNN model achieved the fewest misclassifications overall. However, misclassification patterns revealed limitations: for example, some HER2-negative breast cancer samples were misclassified due to low expression intensity, suggesting the model may struggle with borderline expression thresholds. The SVC model had higher false positives in colorectal-pancreatic overlap cases, likely due to shared CEA expression. These findings highlight the CNN’s ability to abstract complex nonlinear patterns, but also underscore the need for improved discrimination in clinically ambiguous cases.Comparative analysis showed that MLP misclassifications were distributed across less dominant biomarkers like CA-125 and AFP, possibly due to reduced signal variability. In contrast, CNN concentrated misclassifications in borderline expression zones—showing better pattern recognition but still susceptible to edge cases.

ROC curve analysis: model discrimination ability

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves provide another perspective on model performance by measuring the trade-off between sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (false positive rate). The CNN model achieved the highest Area Under the Curve (AUC) score, indicating superior discrimination ability between cancer and non-cancer cases (Fig. 7). The Decision Tree model also performed well, benefiting from its ability to capture non-linear relationships between biomarkers. The relatively lower AUC scores for SVC suggest that traditional machine learning models may struggle with highly complex gene expression data compared to neural networks.The ROC curve confirmed CNN’s superior sensitivity and specificity balance (AUC = 0.97), validating its use in biomarker-based classification.While CNN achieved the highest AUC (0.97), the shape of the ROC curve indicated a strong balance between sensitivity and specificity. In clinical settings, this translates to fewer missed cancer cases (false negatives) and fewer false alarms (false positives). MLP and Decision Tree also performed well, but the slightly lower AUCs (0.91–0.89) reflect reduced robustness, particularly on rare biomarker subtypes. SVC showed the flattest ROC curve, confirming its poor generalization in complex data. These differences validate CNN’s use for high-stakes diagnostic tasks where precision is critical.The superior AUC of CNN reflects its ability to learn hierarchical, non-linear relationships, outperforming MLP in distinguishing overlapping classes. MLP’s performance drop suggests that shallow feedforward networks may not adequately separate complex gene expression boundaries.

3.3.5. Feature importance analysis: validating CEA and HER2

The Decision Tree feature importance analysis highlights CEA and HER2 as the most informative biomarkers, with importance scores of 0.35 and 0.30, respectively. This confirms that these biomarkers significantly enhance the model’s predictive performance. In contrast, other biomarkers such as AFP, PSA, and CA-125 had lower importance scores, reinforcing the idea that CEA and HER2 play a more critical role in cancer classification (Fig. 8). The Shannon entropy-based analysis further validates this finding, indicating that these biomarkers contribute more to reducing classification uncertainty. To enhance interpretability, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis was applied to the CNN output layer. HER2, CEA, and CA-125 contributed the largest positive SHAP values, confirming their predictive dominance. Grad-CAM heatmaps visualized high activation zones corresponding to HER2 and CEA expression peaks, providing transparency to CNN decision-making.

CNN model architecture and its effectiveness

The provided neural network architecture visualization represents the structure of a deep learning model, likely corresponding to the CNN used in this study. The architecture consists of multiple layers that extract hierarchical patterns from gene expression data. Architecture details: Input layer (20 features) → Conv1D (filters = 32, kernel = 3, ReLU) → MaxPooling1D → Conv1D (filters = 64, kernel = 3, ReLU) → Flatten → Dense (128, ReLU) → Dropout (0.4) → Dense (1, Sigmoid). Trained for 100 epochs with Adam (lr = 0.001, batch = 16). Implementation reproducible via TensorFlow 2.13 with fixed random seed (Fig. 9).

The widening and narrowing of the layers in the visualization suggest feature expansion and compression, crucial for deep learning models. Early layers detect simple patterns, whereas deeper layers extract higher-order, disease-specific features, leading to more accurate predictions. The dense connectivity in the hidden layers further enhances the model’s learning capacity.

String protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis

The STRING-based protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, which maps interactions between cancer-associated biomarkers. This visualization shows how key proteins such as HER2, AKT1, JAK1, PIK3CA, and PTEN interact in oncogenic pathways.

The densely interconnected structure of this network indicates a high degree of functional interaction, where mutations or dysregulations in one protein can cascade into broader signaling disruptions. The involvement of PIK3CA, AKT1, and PTEN further validates their role in PI3K-Akt pathway regulation, which is critical in tumor growth and drug resistance (Fig. 10). The strong connectivity of HER2 and JAK1 aligns with their enrichment in EGFR resistance and JAK-STAT pathways, confirming their role in tumor proliferation, immune escape, and therapy resistance.

Gene ontology (GO) & KEGG pathway enrichment analysis

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, highlights the biological pathways in which the identified cancer biomarkers play a role. The fold enrichment on the x-axis indicates the overrepresentation of these pathways, while the color intensity corresponds to the false discovery rate (FDR). The size of each dot represents the number of genes involved in each pathway. Among the most significantly enriched pathways, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance shows the highest fold enrichment, suggesting that biomarkers such as HER2 and EGFR are crucial in drug resistance mechanisms. This is particularly relevant in lung and breast cancer, where targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have shown varied responses. Other major cancer pathways enriched include colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, platinum drug resistance, and PD-L1 checkpoint regulation, reinforcing the role of these biomarkers in tumorigenesis and immune evasion. Emerging literature reports HER2 cross-talk with PD-L1 expression via PI3K-Akt signaling, modulating immune evasion (Zhou et al., 2024). Similarly, CEA upregulation has been observed in HPV-positive cervical and oropharyngeal tumors, implicating viral oncogenesis (Yamada et al., 2023). These findings support the enrichment of viral carcinogenesis and PD-L1 checkpoint pathways in our dataset.

Additionally, involvement in PI3K-Akt and JAK-STAT signaling pathways indicates their role in cell survival, proliferation, and metastasis, highlighting potential targets for precision oncology therapies. The enrichment of viral infection pathways (HIV, HPV, and human cytomegalovirus) further suggests that these biomarkers may play a role in virus-induced oncogenesis. Hierarchical clustering dendrogram, which groups functionally related pathways based on statistical significance (p-values) (Figs. 11 and 12). The closer two pathways are in the tree, they are closer functionally.

The clustering reveals that EGFR resistance, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and platinum drug resistance form a distinct group, suggesting a common regulatory mechanism among them. Similarly, PI3K-Akt and JAK-STAT signaling pathways cluster together, reinforcing their role in intracellular signaling cascades that drive cancer progression. Another major cluster includes PD-L1 checkpoint, apoptosis, and inflammation-related pathways, linking the immune response to tumor development.

This clustering highlights that biomarkers such as HER2, EGFR, and CEA are functionally interconnected through multiple oncogenic pathways, making them strong candidates for multi-targeted cancer therapies (Table 3).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of cancer biomarkers [https://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?pathway:hsa01521, KEGG PATHWAY: hsa01521].

The Table 3 presents key cancer-related genes, their chromosomal locations, and functional descriptions, helping to identify their role in tumor progression, apoptosis, immune regulation, and therapy resistance.

Symbol | Ensembl Gene ID | Entrez | Type | Species | Chromosomes | Position (Mbp) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

MTOR | ENSG00000198793 | 2475 | Coding | Human | 1 | 11.1065 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase |

JAK1 | ENSG00000162434 | 3716 | Coding | Human | 1 | 64.8332 | Janus kinase 1 |

IL6R | ENSG00000160712 | 3570 | Coding | Human | 1 | 154.4052 | Interleukin 6 receptor |

RAF1 | ENSG00000132155 | 5894 | Coding | Human | 3 | 12.5821 | Raf-1 proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase |

PIK3CA | ENSG00000121879 | 5290 | Coding | Human | 3 | 179.1481 | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha |

CASP3 | ENSG00000164305 | 836 | Coding | Human | 4 | 184.6277 | Caspase 3 |

PTEN | ENSG00000171862 | 5728 | Coding | Human | 10 | 87.8626 | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

AKT1 | ENSG00000142208 | 207 | Coding | Human | 14 | 104.7693 | AKT serine/threonine kinase 1 |

BCL2 | ENSG00000171791 | 596 | Coding | Human | 18 | 63.1233 | BCL2 apoptosis regulator |

BAX | ENSG00000100788 | 581 | Coding | Human | 19 | 48.9548 | BCL2-associated X, apoptosis regulator |

MAPK1 | ENSG00000100030 | 5594 | Coding | Human | 22 | 21.7597 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 |

PTEN | ENSG00000284792 | 5728 | Coding | Human | CHR_HG2334_PATCH | 87.8634 | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

In addition to canonical PI3K-Akt and JAK-STAT signaling, KEGG enrichment revealed potential involvement in viral carcinogenesis (HPV, CMV) and immune-related pathways (e.g., PD-L1 checkpoint regulation)39. These unexpected enrichments suggest HER2 and EGFR may also be involved in virus-induced oncogenesis and immune evasion—offering less-characterized avenues for therapeutic targeting (Fig. 13). While canonical oncogenic pathways like PI3K-Akt, JAK-STAT, and MAPK signaling were significantly enriched—consistent with the inclusion of HER2, EGFR, and AKT1—several unexpected pathways were also identified. Notably, viral infection-related pathways (e.g., human cytomegalovirus and HPV infection), immune checkpoint regulation (e.g., PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint), and platinum drug resistance emerged with significant enrichment scores. These associations suggest that selected biomarkers may play additional roles in virus-driven oncogenesis and immune evasion, which merit further investigation.

The KEGG and STRING analyses confirmed well-established oncogenic pathways such as PI3K-Akt and JAK-STAT, expected due to selection of HER2, EGFR, and AKT1. However, lesser-discussed but significant pathways—such as viral infection signaling (HPV, CMV), PD-L1 immune checkpoint regulation, and chemotherapy resistance (e.g., platinum-based drugs)—were also enriched. These underreported associations suggest broader biological functions for key biomarkers, especially in the context of immunotherapy or viral-oncogenesis. Future work could explore these pathways experimentally or through larger genomic datasets39.

Clinical relevance and integration potential

Although this study is simulation-based, the framework is intended for future clinical integration. Biosensor outputs can be fed into EHRs via HL7/FHIR, triggering alerts and risk scores. Challenges include device interoperability, alarm fatigue, and clinician trust. No clinician or patient feedback was collected, and future work should include usability studies and clinical pilots to validate the system in a real-world oncology workflow.

Discussion

Cancer biomarkers are biological indicators that signal the presence, progression, or treatment response of cancer. These biomarkers can be genes, proteins, nucleic acids, hormones, or metabolic products found in blood, tissues, or bodily fluids23. They play a crucial role in early cancer detection, diagnosis, prognosis evaluation, and monitoring treatment response. Unlike traditional diagnostic methods that often detect cancer at later stages, biomarkers enable earlier and more precise detection, improving survival rates and allowing for more personalized treatment strategies24.

Cancer biomarkers serve as crucial molecular indicators for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment monitoring. The advent of gene expression analysis has revolutionized biomarker identification, offering deeper insights into tumor biology and progression25. In this study, we analyzed gene expression data from 285 cancer patients, focusing on five key biomarkers: PSA, HER2, CEA, CA-125, and AFP. Through STRING-based protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment, HER2 and AKT1 emerged as significant hub genes involved in oncogenic pathways such as PI3K-Akt, JAK-STAT, and MAPK signaling26.

Our study evaluated the effectiveness of IoT-enabled biosensors—wearable, implantable, and portable—in detecting and monitoring cancer biomarkers. Each biosensor type demonstrated varying degrees of sensitivity and efficiency across different biomarkers17. Electrochemical sensing based on the Nernst equation identified CEA (−0.133 V) and HER2 (−0.130 V) with high efficiency. This highlights the potential of wearable biosensors in non-invasive, real-time cancer detection. However, PSA and AFP exhibited lower electrochemical responses, necessitating alternative detection techniques such as enzyme-enhanced electrochemical amplification. Optical absorbance modeling using Beer’s Law revealed AFP (0.26 A) as the most detectable biomarker27. HER2 and CEA also showed moderate absorbance, indicating their suitability for implantable biosensors equipped with nanoplasmonic technology. Conversely, PSA and CA-125 exhibited weak optical signals, limiting their effectiveness in implantable devices28. Wireless transmission efficiency, modeled using the Shannon-Hartley theorem, demonstrated the highest data transmission rate for CEA (51.7 Mbps), followed by HER2 (50.6 Mbps). These results emphasize the feasibility of real-time remote monitoring for these biomarkers. AFP, however, exhibited weaker transmission efficiency, suggesting the need for signal amplification or enhanced bandwidth allocation29.Our model assumes that gene expression levels correlate with protein abundance, which is critical for biosensor simulation. While this correlation varies, published studies confirm strong mRNA-protein concordance for HER2, AFP, and CEA in oncology settings28. We acknowledge that this assumption may not generalize across all genes, and its reliability depends on the biomarker class and tissue type.

Literature supports the effectiveness of IoT-enabled biosensors in improving early cancer detection. Studies have shown that continuous monitoring of biomarkers significantly enhances the chances of early intervention, leading to improved survival rates. Real-time biosensor data allows oncologists to detect minute fluctuations in biomarker levels, enabling early-stage diagnosis before clinical symptoms manifest22. Unlike traditional biopsy-based biomarker testing, biosensors offer a non-invasive, real-time monitoring approach, reducing patient discomfort and hospital visits. The use of wearable and implantable biosensors eliminates the need for repeated blood draws, making cancer monitoring more accessible and patient-friendly. The integration of AI-driven predictive models, particularly CNNs, has been demonstrated to enhance diagnostic accuracy significantly30. Several studies have reported CNN-based models achieving accuracy levels above 95% in biomarker classification tasks. This suggests that AI-based biosensor monitoring could outperform traditional diagnostic methods in cancer detection and classification. The implementation of remote biosensor-based monitoring systems has the potential to reduce hospital dependency and healthcare costs31. Studies suggest that continuous at-home monitoring minimizes the need for in-hospital diagnostic tests, allowing for more efficient resource allocation. This is particularly beneficial for low-resource settings where frequent hospital visits are not feasible32.

The integration of IoT into cancer biosensors introduces significant data privacy and security challenges. To address this, data transmission must use secure protocols such as TLS/SSL. Device authentication should be implemented using cryptographic keys and blockchain-based identity management. Furthermore, federated learning can be employed to ensure that sensitive patient data never leaves local devices, while still enabling model updates. Edge computing can reduce the dependency on centralized servers, lowering the risk of data breaches.Although the model showed high performance, we acknowledge that small sample sizes may inflate results, especially in complex models like CNNs. Cross-validation, regularization, and dimensionality reduction were applied rigorously to reduce this risk. In future work, external validation on independent cohorts will be necessary to confirm these results.

Some researchers argue that biosensor technology still lacks the specificity needed for widespread clinical application. False positives and false negatives remain a challenge, particularly in distinguishing between cancerous and benign biomarker fluctuations. This raises concerns regarding unnecessary anxiety and overtreatment in patients33. The large-scale adoption of IoT-enabled biosensors raises concerns about patient data privacy and cybersecurity. Unauthorized access to real-time biomarker data could lead to ethical and legal challenges in data protection. Without robust encryption and security measures, patient confidentiality may be compromised. While biosensors have shown promising results, their sensitivity and specificity vary across different biomarker types34. Some biomarkers, such as PSA and CA-125, exhibit lower detection efficiency, limiting their effectiveness in biosensor applications. This suggests that biosensors may not yet be reliable for all cancer types. The translation of biosensor technology from research to clinical practice requires rigorous validation and regulatory approvals. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory bodies impose strict guidelines for medical devices, which can slow down the adoption of biosensor-based diagnostics. Until these technologies receive widespread clinical validation, their real-world implementation remains uncertain35.

The integration of AI-driven models significantly improved biomarker classification. Feature selection using Shannon entropy ranked biomarkers based on their predictive value, with CA-125, HER2, and CEA exhibiting the highest entropy scores (~ 0.52, ~ 0.50, and ~ 0.50, respectively), reinforcing their diagnostic significance. Four ML models—Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Decision Tree, Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)—were evaluated for biosensor data classification36. The CNN model achieved the highest accuracy (97.2%), outperforming SVC (91.3%), Decision Tree (93.5%), and MLP (94.8%). The superior performance of CNNs underscores their ability to extract complex patterns from biosensor-generated data, making them the preferred choice for AI-enhanced cancer diagnostics37.

While the biosensor simulations were validated using known constants and signal ranges, full device validation (e.g., fabricated sensor prototypes) remains a future step. Calibration curves were included for AFP optical absorbance to validate Beer’s Law modeling. CNN’s predictive accuracy was supported by entropy-based feature selection and dropout regularization. Additionally, KEGG enrichment of immune and viral pathways—beyond expected PI3K-Akt involvement—offers novel biological insights, particularly relevant for HER2 and EGFR in viral-oncogenesis contexts.While promising, these biosensor models rely on computational assumptions rather than physical validation. Real-world implementation would require sensor prototyping, material-specific calibration, and biocompatibility testing, which are not addressed in this theoretical study.

For biosensor-based diagnostics to be adopted in clinical settings, several integration issues must be addressed. These include compatibility with electronic health records (EHRs), development of user-friendly clinician dashboards, integration with hospital alert systems, and compliance with regulatory standards like FDA or CE certification. Moreover, real-time usability studies and clinician feedback must guide interface design to avoid alarm fatigue and ensure actionable alerts.Although the study integrates gene expression, biosensor simulations, and AI classification models, its current implementation remains theoretical. Real-world validation—such as sensor calibration, biocompatibility testing, and patient data correlation—is outside the scope and reserved for future work.

This study underscores the transformative potential of IoT-enabled biosensors combined with AI-driven predictive modeling in cancer diagnostics. The integration of gene expression profiling, real-time biosensing, and deep learning significantly enhances biomarker detection accuracy and monitoring capabilities. The CNN model demonstrated superior performance, validating the effectiveness of AI-based classification. STRING-based pathway analysis confirmed the biological significance of key biomarkers, reinforcing their role in tumor progression and therapy response. While the literature strongly supports the advantages of IoT-enabled biosensors in cancer detection, opposing arguments highlight challenges related to accuracy, data security, and regulatory hurdles. Addressing these limitations through enhanced biosensor sensitivity, improved data security frameworks, and rigorous clinical validation will be crucial for widespread adoption. By enabling continuous, non-invasive monitoring, this approach paves the way for precision oncology, reducing hospital dependency and enhancing remote patient care. Future innovations in biosensor technology and AI analytics will further optimize early cancer detection, ultimately improving patient survival rates and quality of life.

Conclusion

The CNN model demonstrated the highest accuracy among machine learning approaches, reinforcing the efficacy of AI in cancer diagnostics. STRING-based pathway analysis further validated the biological relevance of key biomarkers, linking them to critical oncogenic pathways. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in terms of sensitivity, data security, and regulatory compliance. Addressing these limitations through enhanced biosensor technology, robust data encryption, and comprehensive clinical validation will be essential for large-scale adoption. The proposed system shows strong diagnostic potential, but clinical adoption will depend on validation in hospital environments, usability evaluation, and stakeholder engagement to ensure real-world relevance.

Limitations and future directions

This study presents a computational framework integrating gene expression analysis, biosensor modeling, and machine learning; however, it lacks experimental or clinical validation. The biosensor models based on the Nernst equation, Beer’s Law, and Shannon-Hartley theorem are purely theoretical and have not been validated through physical fabrication or wet-lab experiments. Moreover, no real-world patient samples or clinician-led usability evaluations were included. In future work, we aim to fabricate the proposed biosensors, validate them with standard calibration curves, and assess their clinical usability in collaboration with hospital settings. We also intend to expand the dataset beyond 285 samples to avoid model overfitting and improve generalizability. The current model does not include uncertainty quantification or error propagation analysis. Each pipeline step (gene expression → protein → biosensor → ML prediction) introduces variability. We plan to fabricate proof-of-concept prototypes using gold–graphene nanocomposites for electrochemical HER2 detection and quartz-based optical microcuvettes for AFP sensing. Key parameters—molar absorptivity, diffusion coefficient, and surface potential—will be empirically calibrated to refine simulation assumptions. These validations will bridge model outputs to measurable hardware responses. Future work will involve a sensitivity analysis to evaluate how input uncertainty influences biosensor simulation and prediction robustness. Future efforts should focus on narrowing the pipeline to emphasize either biosensor hardware prototyping or AI diagnostic performance, supported by patient-derived samples. The current model remains purely computational due to practical constraints. Nonetheless, it lays the groundwork for targeted experimental research by identifying promising biomarkers and viable biosensor mechanisms. The study did not incorporate patient data, EHR integration, or usability testing. It also lacks clinician input or real-time system validation. These gaps should be addressed in a follow-up study with stakeholder collaboration and deployment in a clinical sandbox. The current model was validated only on the GEO-derived dataset. No external or independent dataset (e.g., TCGA or clinical biosensor data) was used. Future work will involve cross-dataset validation and collaboration with clinical laboratories to assess generalizability.

Although this study did not involve fabrication or in-vitro calibration of biosensor prototypes, its objective was to develop a unified theoretical–computational framework to guide future hardware development. In the next phase, we plan to fabricate proof-of-concept electrochemical and optical sensors using gold–graphene electrodes and validate them using standard calibration curves for HER2 and CEA in human serum. These experiments will empirically verify the model-predicted Nernst and Beer–Lambert responses.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from a publicly accessible dataset from [40]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi? acc=GSE68086.

References

Pina-Sanchez, P. et al. Cancer biology, epidemiology, and treatment in the 21st century: current status and future challenges from a biomedical perspective. Cancer Control. 28, 10732748211038735 (2021).

Cooper, G. M. & Hausman, R. E. The development and causes of cancer. The cell: A molecular approach. ;2:725–66. (2000).

Kaur, S., Baine, M. J., Jain, M., Sasson, A. R. & Batra, S. K. Early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer: challenges and new developments. Biomark. Med. 6 (5), 597–612. https://doi.org/10.2217/bmm.12.69 (2012). PMID: 23075238; PMCID: PMC3546485.

Ginsburg, O. et al. Breast cancer early detection: A phased approach to implementation. Cancer 126 (Suppl 10), 2379–2393. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32887 (2020). PMID: 32348566; PMCID: PMC7237065.

Prasanth, B. K., Alkhowaiter, S., Sawarkar, G., Dharshini, B. D. & Baskaran, R. Unlocking early cancer detection: exploring Biomarkers, Circulating DNA, and innovative technological approaches. Cureus 15 (12), e51090. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51090 (2023). PMID: 38274938; PMCID: PMC10808885.

Fass, L. Imaging and cancer: a review. Mol Oncol. ;2(2):115–52. (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molonc.2008.04.001. Epub 2008 May 10. Erratum in: Mol Oncol. 2022;16(15):2896. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13283. PMID: 19383333; PMCID: PMC5527766.

Noyce, A. J., Lees, A. J. & Schrag, A. E. The prediagnostic phase of parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 87 (8), 871–878. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2015-311890 (2016). Epub 2016 Jan 11. PMID: 26848171; PMCID: PMC4975823.

Alieva, M., van Rheenen, J. & Broekman, M. L. D. Potential impact of invasive surgical procedures on primary tumor growth and metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 35 (4), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10585-018-9896-8 (2018). Epub 2018 May 4. PMID: 29728948; PMCID: PMC6063335.

Ming, Y. et al. Progress and future trends in PET/CT and PET/MRI molecular imaging approaches for breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 10, 1301. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01301 (2020). PMID: 32903496; PMCID: PMC7435066.