Abstract

The nonlinear coupled Riemann wave equation serves as a mathematical framework for analyzing the interaction between short and long waves in various physical phenomena. Its importance lies in capturing both soliton-like behaviors and complex instabilities that arise in nonlinear media. Despite this significance, exact solutions for this equation, particularly in fractional-order forms, remain limited. In this article, numerous soliton solutions of the NLCRW equation are derived by applying novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method, thereby advancing the state of the art in analytical wave modeling. By employing several fractional derivatives, including the M-Truncated, β, and Conformable operators, the method produces diverse solution families such as hyperbolic, trigonometric and rational forms. Comparative 2D and 3D visualizations further highlight M-type and singular periodic solitary wave structures across these derivatives. In addition, the dynamic behavior of a perturbed nonlinear Hamiltonian system is investigated using bifurcation analysis, Poincaré sections, and Lyapunov exponents. The bifurcation diagrams and phase portraits reveal regime transitions and underscore the critical role of system parameters. Sensitivity and multistability analyses confirm the influence of initial conditions on long-term dynamics. These results provide insights relevant to ion-acoustic waves in plasma, shallow-water wave propagation, and the transmission of optical pulses, where nonlocal interactions and memory effects play an essential role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear partial differential equations with common properties are important for modeling nonlinear phenomena in science and engineering. To solve these ill-posed problems, it is essential to acquire exact solutions for differential equations, allowing researchers to develop efficient methods for solving linear and nonlinear equations. In recent years, interest in solutions and Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) has increased. Fractional calculus generalizes traditional concepts of differentiation and arithmetic to non-integer orders, leading to the investigation of systems with memory and genetics. Fractional order models and equations are widely used in physics, viscoelasticity, engineering, finance, modeling, biology, electrochemical processes, complex systems, control systems, mechanics, vibration and other fields1,2,3,4.

Fractional calculus is an extension of classical calculus and deals with derivatives and integrals of non-integer order. This detail provides a strong foundation for describing and modeling patterns arising from memories, longevity, and local interactions. In fractional calculus, fractional derivatives (or integrals) are extended beyond determinism to include deterministic numbers and even complex derivatives, allowing the construction of new mathematical models suitable for fractional differential equations. These equations containing fractional components can define processes that differ from traditional behaviors. Recently, many studies have focused on understanding the behavior of PFDEs and solving their problems, such as the time-fractional telegraph equation5, the time-fractional Klein–Gordon equation6, the solution of fractional Phi-4 and the Allen–Cahn equation7, the fractional simplified Camassa-Holm equation8,9, the fractional coupled Burgers equation10, the fractional nonlinear coupled Boussinesq equation11, the space–time fractional Camassa-Holm equation12 and the fractional space–time advection dispersion equation13.

The usage of fractional derivatives to model memory and genetic processes has become widespread in many materials and systems, including polymers. Polymers are multipart materials whose molecular structure exhibits local effects, memories, and time effects that can be accurately termed using mathematical models. In recent years, researchers have used many sorts of fractional derivatives, such as the Atangana beta and conformal derivatives14, Atangana–Baleanu derivative in Caputo manner (ABC) and Caputo–Fabrizio (CF)15, Caputo fractional derivatives16, Grunwald–Letnikov fractional derivatives17, Riemann–Liouville fractional18, modified Riemann–Liouville derivative19,20, Atangana-Baleanu derivative21, and generalized fractional Caputo-Liouville derivative22.

Due to the existence of FPDEs, finding solutions to these equations is an important and difficult part of the research. To solve this difficulty, many ideas have been proposed, including the development of double sub-equation23, modified exp function method24, new-auxiliary equation method25, the new exponential rational function method26, (G′/G)-expansion technique27, bi-variable (G′/G, 1/G)-expansion method28, sine and cosine method29, new exponential expansion method30, two-dimensional inequality left and right traveling wave solutions31, continuous tanh-coth expansion method and the polynomial function method32, Kudryashov expansion method and the simplified bilinear method33, and other34. This technique works by dividing the original equation into a simpler or easier-to-solve modified form.

Additionally, the research paper35 provides an in-depth discussion of the (w/g)-expansion method, where w and g are functions that satisfy the following condition:

where B and C are capricious constants. The latter approach provides the solution of Eq. (1) and provides an explicit formula for evaluating the solution of the nonlinear evolution problem (NEP). This work investigates the (w/g)-expansion technique36, where w and g are functions satisfying the conditions specified in Eq. (1).

if \(A \ne 0\) and we proceeds \(w(\varepsilon ) = \frac{{G^{\prime } (\eta )}}{G(\eta )}\) and \(g(\varepsilon ) = G(\eta ),\) then we have

This modification led to the discovery of several new traveling wave solutions with free parameters for NEP. More details about the modified (G′/G2)-expansion can be found in the research paper37. This method leads to the solution of many different equations. In our present work, we adopt a novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method introduced by Amna et al.38 to search for new solutions to the NLCRW equation. In this paper we examine three fractional derivatives to define the solution of the NLCRW equation39. The beta derivative prolongs the idea of fractional derivatives by presenting alpha and beta from the beta function and provides more flexibility than traditional derivatives such as the Riemann–Liouville or Caputo derivatives. It is worth perceiving that the fractional beta derivative is used less frequently than the other terms. The choice of derivatives depends on the particular problem, the behavior of the model, and the preferred solution. The M-truncated derivative, through its Mittag–Leffler kernel, smooths variations and introduces stronger memory effects, thereby delaying the onset of chaos and stabilizing periodic windows. The β-derivative enhances system sensitivity, producing sharper troughs in wave profiles and leading to an earlier onset of chaos and more complex bifurcation cascades. The conformable derivative exhibits intermediate behavior, preserving the qualitative bifurcation structures while yielding less intense chaotic oscillations compared to the β-derivative. This comparative analysis shows that while all three derivatives preserve the underlying nonlinear structures, they influence the timing and intensity of chaotic transitions differently: the M-truncated derivative suppresses it, the β-derivative accelerates chaos and the conformable derivative offers a balanced response. These findings highlight that the choice of fractional derivative is not only mathematical but also significantly shapes the physical interpretation of nonlinear system behavior.

In this study, a novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method is used to provide the solution of NLCRW equation40 using three different fractional derivatives. This nonlinear equation has important applications in modern communication network technology, especially in the context of tsunami and tidal wave propagation, optical fibers, plasmas, ion-acoustic waves and magneto-acoustic waves in homogeneous and stationary media. The equation is particularly relevant because it captures both localized soliton structures and the onset of instabilities, providing a versatile framework for studying nonlinear wave phenomena. Extending the NLCRW equation into fractional-order forms further enriches its modeling capacity by incorporating non-locality and memory effects, which are essential in many real-world systems where present dynamics depend on the history of the process. Fractional derivatives therefore allow a more realistic description of wave evolution in viscoelastic, dispersive, and heterogeneous environments, making the study of fractional NLCRW equations both timely and significant. The proposed method produces various types of solutions, namely M-shaped solitons, bright solitons and dark solitons. A systematic analysis then leads to the formulation of an unperturbed dynamical system represented by an ordinary first order differential equation. We perform a qualitative analysis of the model, by using this dynamical system, incorporating principles from bifurcation theory, chaos theory, stability analysis, and sensitivity analysis under varying initial conditions. The phenomenon of multistability recognizes several stable states and helps to understand the role of initial conditions in system’s behaviour. However, the Lyapunov exponent measures the rate of divergence between trajectories and thus provides a true measure of the stability and chaos of the system. Furthermore, Poincaré maps help as an important technique for solving nonlinear systems to examine the stability, chaos and differentiate between periodic, quasi-periodic, and chaotic behaviors41,42. These phenomena are studied in different fields of science like engineering, neuroscience, economics, weather forecasting, artificial intelligence, and mathematics.

The aim of this work is to find the soliton solutions of NLCRWE by novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method and to provide the dynamical analysis of the NLCRWE. This paper is ordered into following sections. Definitions of M-truncated, Conformable and Beta derivatives are given in Sect. “Material and method”. The main algorithm of the suggested method is covered in Sect. “The method”. Application of method with the obtained results is given in Sect. “Methodological application”, graphical representation and discussion are covered in Sect. “Results and discussion”. Section “Bifurcation analyses” discovers the bifurcation analysis of the system. Section “Sensitivity analysis” covers the analysis of bifurcation diagram and Sect. “Chaotic analysis” explores the sensitivity analysis of the system. To understand the nonlinear behaviour of the system, Section “Bifurcation diagram” examines chaotic behavior. Multistability analysis is presented in Sect. “Multistability”, illustrating the effect of initial conditions on the system. In Sect. “Poincaré map”, Poincaré maps are presented, and Lyapunov exponents are discussed in Sect. “Lyapunov exponents”. Lastly, Sect. “Conclusion” summarizes the important findings and implications of our work in different fields of science.

Material and method

Beta derivative

Consider a function \(U:[y,\infty ) \to \Re\) that is continuous for \(t \ge 0\,,\,{\text{where }}y \in \Re \,.\) The fractional derivative of U(t) of order \(\, \beta \in \left( {0,1} \right]\), known as \(\beta\)-derivative, is expressed as follows39:

where \(\Gamma \,\) represents the gamma function and defined as:\(\Gamma \left( \nu \right) = \int_{0}^{\infty } {t^{\nu - 1} } e^{ - t} dt\).

Let \(\gamma \left( t \right)\,\,{\text{and }}\,\delta \left( t \right)\,\) be differential functions of order \(0 < \beta \le 1\,{\text{where }}t \ge 0.\)

-

1.

\(D^{\beta } \left( {a\gamma \left( t \right) + b\delta \left( t \right)} \right) = aD^{\beta } \left( {\gamma \left( t \right)} \right) + bD^{\beta } \left( {\delta \left( t \right)} \right),\,\forall a\,,\,b \in \Re .\)

-

2.

\(D^{\beta } \left( {a\gamma \left( t \right)b\delta \left( t \right)} \right) = \gamma \left( t \right)D^{\beta } \left( {\delta \left( t \right)} \right) + \delta \left( t \right)D^{\beta } \left( {\gamma \left( t \right)} \right).\)

-

3.

\(D^{\beta } \left( {\frac{\gamma \left( t \right)}{{\delta \left( t \right)}}} \right) = \frac{{\gamma \left( t \right)D^{\beta } \left( {\delta \left( t \right)} \right) - \delta \left( t \right)D^{\beta } \left( {\gamma \left( t \right)} \right)}}{{\delta \left( t \right)^{2} }}.\)

-

4.

\(D^{\beta } \left( c \right) = 0,\,\) for any constant c.

-

5.

Consider \(\varsigma = \left( {t + \frac{1}{\Gamma \left( \upbeta \right)}} \right)^{1 - \upbeta } \uptheta ,\;\theta \to 0\;{\text{when}}\, \varsigma \to 0,\;{\text{therefore we obtain:}}\)

with \(\chi = \frac{c}{\beta }\left( {t + \frac{1}{\Gamma \left( \beta \right)}} \right)^{\beta } ,\,\) Here, c represents an arbitrary constant. The properties associated with the β-derivative have been proven in the study presented in43.

M-truncated derivative

Let \(U:\left[ {y,\infty } \right) \to \Re \,\) be a continuous function and \(\beta \, \in \left( {0,1} \right]\,,\,\) represent the order of the derivative. The M-Truncated derivative of U(t) is expressed as follows44:

For \(\gamma \,E_{\delta } \left( . \right)\,{\text{and }}t > 0\,,\delta > 0,\,{\text{ and }}\gamma \,E_{\delta } \left( . \right)\) is a truncated Mittag—Leffler function in single parameter defined by45:

THEOREM 2.1. Let \(\beta \in \left( {0,1} \right]\,,\,{\text{and }}K\,,\,L\) are differentiable of \(\beta\) order and \(\delta > 0\,,\,a\,,\,b \in \Re \,\,\).

-

1.

\(D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {aK\left( \psi \right) + bL\left( \psi \right)} \right) = aD_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {K\left( \chi \right)} \right) + bD_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {L\left( \chi \right)} \right),\;\forall a,b \in {\text{R}}.\)

-

2.

\(D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {K\left( \chi \right)L\left( \chi \right)} \right) = K\left( \chi \right)D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {L\left( \chi \right)} \right) + L\left( \chi \right)D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {K\left( \chi \right)} \right).\)

-

3.

\(D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {\frac{K\left( \chi \right)}{{L\left( \chi \right)}}} \right) = \frac{{K\left( \psi \right)D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {L\left( \chi \right)} \right) - L\left( \chi \right)D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( {K\left( \chi \right)} \right)}}{{L\left( \chi \right)^{2} }}.\)

-

4.

\(D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } \left( c \right) = 0,\,{\text{for any constant }}c.\)

-

5.

\(D_{M,\chi }^{\beta } K\left( \chi \right) = \frac{{\chi^{1 - \beta } }}{{\Gamma \left( {\delta + 1} \right)}}\frac{dK}{{d\delta }}.\)

Conformable derivative

Let \(U:\left[ {y,\infty } \right) \to \Re\) be a continuous function and let \(\beta \in \left( {0,1} \right]\) denotes the order of the differentiation. The conformal derivative of U(t) of \(\beta\) order is given by46:

This definition is valid for all t > 0, and confirms the existence of the conformable derivative of order \(\beta .\) Assume that h(t) and f(t)are differential in conformable sense. The conformable derivative satisfies several fundamental properties, listed as follows:

-

1.

\(D_{t}^{\beta } (\lambda ) = 0\,\,\) where \(\lambda\) is a constant.

-

2.

\(D_{t}^{\beta } (t^{\mu } ) = \mu t^{\mu - \chi } ,\) \(\forall \,\mu \in R\).

-

3.

\(D_{t}^{\beta } (a\,h(t) + \,b\,f\,(t))\, = a\,\,D_{t}^{\beta } h(t)\, + b\,D_{t}^{\beta } f\,(t),\) for all \(a\,,b \in R\).

-

4.

\(D_{t}^{\beta } (h(t) + \,\,f\,(t)) = \,h(t)\,D_{t}^{\beta } f(t)\, + \,f(t)\,D_{t}^{\beta } h(t)\).

-

5.

\(D_{t}^{\beta } \left( {\frac{h(t)}{{f(t)}}} \right) = \frac{{\,f(t)\,D_{t}^{\beta } h(t) - \,h(t)\,D_{t}^{\beta } f(t)}}{{f(t)^{2} }}\).

-

6.

If h is differential, then \(D_{t}^{\beta } (h(t)) = t^{1 - \beta } \frac{dh(t)}{{dt}}\).

The method

To begin the analysis, we consider the following nonlinear partial differential equation:

where N is a polynomial composed of \(w = w\left( {x,y,t} \right)\) and its partial derivatives and \(w = w\left( {x,y,t} \right)\) represents an unknown function. The essential steps of the method used here are outlined below:

Step 1: Consider the wave transformation \(\eta = x + y - \omega {\kern 1pt} t\), where \(\omega\) denotes the wave speed. Under this transformation, Eq. (1) reduces to a nonlinear ODE of the form:

Step 2: Consider that the solution of Eq. (5) can be written as a finite series expansion expressed as:

where \(a_{i}\) and H are constants and \((i = \pm \;1,..., \pm \;n)\). The number of terms in the series is determined by equating the highest order derivative and nonlinear terms of Eq. (5). The auxiliary function \(\left( {{{G^{\prime } } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{G^{\prime } } {G^{2} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {G^{2} }}} \right)\) is assumed to obey below Riccati type equation:

where A, B and C are constants. Solutions to this Riccati Eq. (7) yield various forms of the general solution mentioned below:

where, in these cases \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\) and P and Q are arbitrary constants.

Step 3: To derive algebraic equations for determining W and coefficients \(a_{i} (i = \pm \;1,...,\; \pm \;N),\) the powers of the term \(\left( {H + G^{\prime } /G^{2} } \right)^{i} ,(i = \pm \;1,\; \pm \;2,...)\) are collected and their coefficients are set to zero. Equation (6) and (7) are then substituted into Eq. (5) to complete this step.

Step 4: The resulting algebraic equations are solved using computational software such as Maple, leading to determination of W, and \(a_{i} ,(i = \pm \;1,...,\; \pm \;N).\)

After calculating these constants, substitute the value of \(\left( {H + G^{\prime } /G^{2} } \right)\) from Eq. (8) into Eq. (6) to derive the exact solutions of Eq. (4).

A comparison table of the traditional (G′/G)-expansion method and the proposed novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method is presented below. The novel modified method gives broader solution families, greater flexibility and stronger applicability to fractional models.

Methodological application

The (2 + 1)-dimensional Coupled Riemann Wave Equation39 is taken as a case study in this section:

where l, m, n are non-zero parameters. These parameters have physical explanations linked to nonlinear wave propagation. The parameters l, m and n are dispersion and coupling coefficients that determine how the short and long waves act during evolution. Specially, l controls the effect of linear dispersion on the wave structure, whereas m and n define nonlinear coupling between the W and F, adjusting the strength and symmetry of their collaboration. The constants A, B and C arise in the formulation of travelling-wave solutions and represent scaling amplitudes and phase shifts. In fact, they capture the role of initial and boundary conditions in shaping the resulting solitary or periodic wave structures. Understanding these constants in wave-related terms allows the mathematical solutions to be connected with noticeable characteristics like sharpness, amplitude and localization of the nonlinear waves.

The Eq. (9) can be rewritten using the \(\beta\)–derivative in the following form:

In above equation, l, m, n are non-zero parameters and deliberate the relation among the propagation of a Riemann wave and a long wave,\(D_{\beta ,t}^{\gamma }\) represents \(\beta\)–Derivative of W(x, y, t) where \(\gamma\) is a derivative of fractional order satisfying \(0 \le \gamma \le 1.\)

Using M-Truncated Derivative, Eq. (9) becomes:

where \(\gamma\) is parameter of fractional order \(D_{M,t}^{\gamma }\) is M-Truncated Derivative.

Using Conformable Derivative, Eq. (9) becomes:

where \(\gamma\) is fractional operator and \(D_{C,t}^{\gamma }\) is Conformable Derivative.

The travelling wave parameter \(\eta\) has three distinct definitions when considering the wave transformation.

In \(\beta\)-Derivative, \(\eta\) is expressed as follows:

where \(\mu \,,\,\sigma \,{\text{and }}\nu \ne 0\).

In M-Truncated derivative, \(\eta\) is expressed as follows:

In Conformable Derivative, \(\eta\) is expressed as follows:

By applying the respective wave transformations given in Eqs. (13), (14), and (15) to Eqs. (10), (11), and (12), the system is reduced to a set of ordinary differential equations as follows:

taking the zero integration constant after integrating the second equation of (16), we get

By putting Eq. (17) into Eq. (16) after integration, we obtain:

Now the highest ordered non-linear and linear terms of Eq. (18) are balanced, and we get the balance number i.e. N = 2. Now utilizing N = 2, Eq. (6) can be expressed as:

Here, \(G = G\left( \eta \right)\,,{\text{and the constants }}a_{0} \,,a_{1} \,,a_{2} \,,a_{ - 1} ,\,a_{ - 2} \,\,\) are to be determined. By substituting Eq. (19) along with Eq. (7) into Eq. (18) and equating the coefficients of power of \((H + G^{\prime } /G^{2} )^{i} ,\;(i = 0,\; \pm 1,\; \pm \;2,...)\) to zero, we derive a system of nonlinear equations. This system is then solved using Maple 10, yielding the following parameter sets.

Set 1:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Set 2:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Set 3:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Set 4:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Set 5:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Set 6:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Set 7:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Set 8:

Substituting the determined constants into Eq. (19) and applying the various solutions from Eq. (8), following five distinct cases are derived.

Case 1: For the condition \(AB > 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 2: For the condition \(AB < 0\,{\text{and}}\,C = 0\), the corresponding hyperbolic solution is obtained as follows:

Case 3: For the condition \(A = C = 0\,{\text{and}}\,B \ne 0,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 4: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta \ge 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB\,,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

Case 5: For the condition \({\kern 1pt} C \ne 0\,{\text{and}}\,\Delta < 0\) where \(\Delta = C^{2} - 4AB,\) the corresponding solution is obtained as follows:

where \(\,\eta = \mu \,x + \sigma \,y - \frac{{\nu \,\left( {t + \tfrac{1}{\Gamma \left( \beta \right)}} \right)}}{\beta }^{\beta } ,\) \(\,\zeta = \mu \,x + \sigma \,y - \nu \frac{{\Gamma \left( {\delta + 1} \right)\,}}{\beta }t^{\beta }\) and \(\,\zeta = \mu \,x + \sigma \,y - \frac{\nu \,}{\beta }t^{\beta }\) are correspond to the wave transformations in all the eight solution sets as discussed earlier.

Results and discussion

This study solves the NLCRW Equation using a few fractional derivative operators. Utilizing conformable, Beta and M-truncated derivatives, novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method, a dependable integration technique, is utilized to achieve the results. The outcomes generated by the method for three distinct fractional derivative operators are visualized through 2-D time evolution plots and 3-D graphical representations. The many kinds of optical solitary wave solutions, such as M type and singular periodic solitons are provided by this approach. It is very helpful to compare Conformable-Derivative with Beta and M-Truncated derivatives, precisely utilizing 2-D time evolution graphics. Minor shifts in the wave profile are observed with variations in the fractional derivative, although the overall shape of the curve remains consistent. This proves the symmetry of travelling wave solutions. If the values of parameters get different particular values, a single solution might result in the generation of numerous different types of solutions. The soliton solutions were obtained using novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion technique. They offer a graphic depiction of the temporal and spatial behaviours of travelling waves. The graphical representations of the exact solutions clearly demonstrate that novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method has been found to be dependable and efficient.

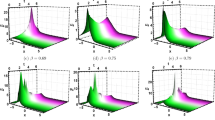

Figure 1 demonstrates the temporal and spatial evolution of the wave profile W2,2 using three different fractional derivative operators: β-derivative, M-truncated derivative, and conformable derivative. Figure 1a represents the β-derivative case, displaying a symmetric soliton-like structure with a noticeable central peak, while Fig. 1b,c demonstrate minor variations in amplitude and width under the M-truncated and conformable derivatives, respectively. In spite of these small shifts, the overall structure of the wave remains unchanged, indicating the robustness and symmetry of the travelling wave solutions. The 3D plots further confirm the uniformity of the soliton profile across the time domain, with all three cases showing stable wave propagation and temporal consistency. These visualizations validate that the novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method effectively maintains solution reliability under different fractional operators.

2D, time evolution (at t = 0, 1, 2) and 3D plots show the two-peak M-type soliton solution W2,2 using m = 0.3, l = 0.6, n = 0.2, A = − 4, B = 1, C = 0, P = 1, Q = 3, σ =− 0.2, µ = 0.4 and different fractional derivatives (a) Illustrates the solution using fractional order 0.6 and β -Derivative, (b) Shows the solution using fractional order 0.6,\(\gamma\) = 1.3 and M-Truncated Derivative. (c) Shows Conformable Derivative using fractional order 0.6. The solitons show a central peak with slight changes in width and amplitude, confirming the symmetry of the travelling wave, showing that the soliton preserves its overall shape using different derivative types.

On the other hand, Fig. 2a,b,c demonstrate the wave profile W6,1. In Fig. 2, the dynamics become more complex, with the wave structure showing sharper troughs and singular behavior, especially visible in Fig. 2a. These suggest the existence of singular periodic soliton characteristics that are more sensitive to the type of fractional derivative used. Although the overall wave shape stays similar, the dips become deeper and steeper when using the β-derivative as compared to the M-truncated and Conformable derivatives. The 3D graphs support this observation, showing deeper and more intense troughs as time evolves. This comparison elaborates the effect of derivative choice on the solution structure, strengthening the value of the proposed method in capturing distinct physical behaviors of nonlinear systems across fractional models.

2D, time evolution (at t = 0, 1, 2) and 3D plots show singular periodic soliton solution of W6,1 for l = 0.6, m = 0.3, n = 0.2, A = 4, B = 1, C = 0, P = 1, Q = 3, σ =− 0.2, µ = 0.4, (a) Illustrates the solution using fractional order 0.6 and β -Derivative, (b) Shows the solution using fractional order 0.6,\(\gamma\) = 1.3 and M-Truncated Derivative. (c) Shows Conformable Derivative using fractional order 0.6. Dynamics are intricate with sharp troughs and deeper dips especially under the β-derivative, while the other operators yield smoother troughs.

The nonlinear dynamics observed here complement the soliton solutions obtained in the first part of the study: while the analytical method provides localized traveling waves that describe coherent structures, the bifurcation and chaos analysis reveals how these structures can destabilize and evolve into complex oscillatory patterns under parameter perturbations. Together, these two perspectives highlight the dual nature of the NLCRW equation, capable of supporting both stable solitary waves and chaotic dynamics, depending on the parameters regime.

Comparison of the Proposed Modified (G′/G2)-Expansion Method with the Traditional (G′/G)-Expansion Method.

Characteristics | Traditional (G′/G)-Expansion Method | Proposed Novel Modified (G′/G2)-Expansion Method |

|---|---|---|

Solution types | Mainly hyperbolic and trigonometric forms | Broader classes including hyperbolic, trigonometric, rational |

Flexibility | Limited parameter control, solution families often narrow | Additional free parameters allow richer structures and more general forms |

Handling of singularities | Weak in capturing rational/singular behaviors | Capable of generating rational and singular periodic solutions |

Adaptability to fractional operators | Less effective for nonlocal/fractional derivatives | Naturally accommodates conformable, β, and M-Truncated derivatives with consistent results |

Analytical efficiency | Requires more balancing steps to match nonlinear terms | More direct balancing procedure reduces algebraic complexity |

Physical relevance | Solutions often idealized or symmetric | Produces waveforms with adjustable amplitude and width, closer to physical solitary and periodic patterns |

Bifurcation analyses

Bifurcation analysis investigates the behavior of dynamical systems as parameters vary, irrespective of whether those parameters are interdependent. The second-order differential Eq. (18) can be reformulated into a system of two first-order equations using the Galilean transformation, as outlined in references47,48:

where \(F_{1} = \frac{\nu }{{\mu \sigma^{2} \,l}}\), \(F_{2} = \frac{m + n}{{2\sigma^{2} \,l}}.\)

The following set of equilibrium points makes up the system:

Once we have the fixed points, we can analyze the stability of these points by computing the Jacobian matrix of the system. It is given by:

The Jacobian gives a linear approximation of the system near the fixed or equilibrium points and helps classify these points as saddle points or center points based on the eigenvalues. This analysis is fundamental in understanding the local stability of a dynamical system.

The Hamiltonian function, representing the total energy of the system, combines both kinetic and potential energy components. Specifically, the kinetic term is quadratic in the velocity variable z, while the potential energy is expressed as a nonlinear function of the displacement F, involving both quadratic and cubic terms. This formulation allows the system’s trajectories to be analyzed in terms of energy level curves, offering valuable insights into the qualitative nature of motion, particularly near equilibrium points and during bifurcation transitions.

It satisfies the canonical equations:

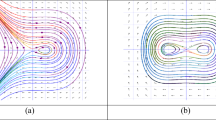

The three phase portraits showcase a variety of Hamiltonian energy landscapes driven by changes in the parameter sets (F1 and F2). The phase portrait in Fig. 3a exhibits a saddle-type behavior around an unstable equilibrium point (0, 0) marked by the red dot. The contour lines form a hyperbolic pattern, characteristic of a saddle point in Hamiltonian systems. Trajectories diverge away from this point along distinct separatrices, indicating sensitive dependence on initial conditions and lack of periodic motion.

In Fig. 3b, the phase portrait reveals the presence of two distinct equilibrium points: a center at (1, 0) and a saddle at the origin (0, 0), represented by the green and red markers, respectively. Around the center, the trajectories form closed elliptical loops, indicating stable and periodic behavior in that localized region. Beyond this central area, the influence of the saddle point becomes apparent, introducing a more complex structure where trajectories may either split apart or diverge. This reflects the coexistence of both stable and unstable regions within the system’s dynamics.

The phase portrait in Fig. 3c shows entirely closed and elliptical paths centered around a stable point at (0, 0), marked by the green dot. The motion across the entire phase space is periodic and conservative, as there are no saddle points or separatrix structures disrupting the flow. This setup implies that no matter the initial condition, the system remains confined within fixed energy levels, reflecting consistent, stable oscillations throughout which is an indication of overall stability in the system’s behavior.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis of a system examines how small changes in initial conditions affect the future behavior of the system. This investigation is crucial in understanding the predictability, stability, and chaotic nature of the system which is vital in domains like engineering, physics, and control systems where exact initial conditions are unachievable49,50.

The plot in Fig. 4a displays the time response of the system variable F(t) under three initial conditions: [0.01, 0.01], [0.20, 0.20], and [− 0.1, − 0.1]. Across all trajectories, the system exhibits sustained, bounded oscillations without any sign of divergence or instability. Although the amplitude varies with the magnitude of the initial condition, the overall behavior remains regular and periodic. This suggests that the system can absorb a range of perturbations while preserving a stable dynamic regime. The consistent response across different initial states points to the presence of a stable nonlinear structure, such as a limit cycle or conservative motion. The plot in Fig. 4b shows the time evolution of the variable F(t) under three initial conditions: [0.01, 0.01], [0.21, 0.21], and [− 0.11, − 0.11]. The resulting trajectories remain bounded and periodic, with noticeably smaller amplitudes compared to previous cases. This indicates that the system is operating in a more damped or less energetically responsive regime. Regardless of the minor differences in initial states, the system maintains consistent, stable oscillations, further affirming its resistance to divergence and chaotic transitions. Overall, the behavior points to a reliably stable dynamic response within a slightly perturbed initial conditions.

Chaotic analysis

In this section, we add an external force in the dynamical system (68) to make it perturbed as shown below:

where \(\rho \cos \left( {\tau \,\eta } \right)\) is known as perturbation term. In your system of equations, τ represents the frequency of the external perturbation, determining how often the external force oscillates over time, while ρ is the amplitude of the perturbation, controlling the strength of the external force51,52. The term ρcos(τ) models this periodic forcing. A higher τ means faster oscillations, and a larger ρ means a stronger force. Together, they define the nature of the perturbation, with stronger and more frequent forces potentially driving the system toward more complex or chaotic behavior, while weaker or slower perturbations tend to produce smoother, more regular dynamics.

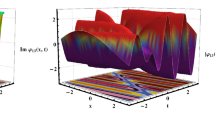

Figure 5 shows distinct signatures of chaotic behavior under the parameter setting ρ = 1.5, τ = 4, with F1 = − 2, F2 = − 1. The 2D phase portrait (a) reveals a densely packed structure with overlapping loops, suggesting sensitive dependence on initial conditions. In the 3D trajectory (b), the motion extends in a helical pattern over time, reinforcing the presence of a strange attractor with complex geometry. The time series plots (c) clearly demonstrate irregular oscillations in both F and z, with no apparent periodicity, confirming the presence of non-repeating, bounded behavior. Collectively, these characteristics strongly indicate a chaotic regime with rich dynamic variability.

In Fig. 6, the system is analyzed for ρ = 3 and τ = 3 and the parameter set F1 = − 3, F2 = − 3. The 2D phase plot (a) displays thick, nested loops, signifying strongly irregular oscillations and sensitive to initial conditions. The 3D phase portrait (b) strengthens this behavior, with the trajectory forming a tangled spiral arrangement that shows persistent chaotic pattern. The time series plots (c) of both F and z illustrate quick and irregular oscillations without repeating patterns, further describing the presence of chaos. Together, these characteristics validate that under the selected parameters, the system demonstrates strong chaotic dynamics with noticeable instability.

Figure 7 explores the system’s behavior with parameters ρ = 4.5 and τ = 3 and F1 = − 4, F2 = 1. The 2D phase portrait (a) features broad, circular loops with clearer spacing, indicating more regular and less sensitive trajectories. The 3D phase space (b) supports this with a visibly layered structure, forming smooth coils over time. In the time series plots (c), the oscillations in both F and z appear quasiperiodic, with some repetition and structure visible across the time domain. This suggests the system is either in a weakly chaotic or quasiperiodic state, reflecting a more predictable, less turbulent regime compared to the previous cases.

Bifurcation diagram

Bifurcation diagrams are used to understand how the qualitative behavior of a dynamical system changes as a key parameter is varied. This technique helps reveal critical transitions known as bifurcations where the system may shift from stability to instability, from periodic motion to chaos, or from a single steady state to multiple coexisting solutions. By visualizing these changes, researchers can identify thresholds where small parameter adjustments lead to significant differences in long-term outcomes. Bifurcation diagrams are especially valuable in nonlinear systems, where analytical solutions are often difficult or impossible to obtain. They offer a powerful way to map the global structure of the phase space, detect regions of multistability, and predict the onset of complex phenomena such as oscillations, hysteresis, or chaotic dynamics53,54.

In Fig. 8a, the bifurcation diagram with F2 as the control parameter and fixing F1 = − 2 and ρ = 1.5 shows a sequence of periodic paths into chaos. For small F2, the system remains periodic with stable oscillations, but as F2 increases, complex twigs appear, showing chaotic transitions. On the other hand, In Fig. 8b, when ρ is varied while fixing F1 = − 2, F2 = 1, the bifurcation diagram illustrates a broader chaotic state with thick oscillatory bands. Periodic paths appear occasionally, but chaotic behaviour is prominent for larger values of ρ. Collectively, these findings show that both F2 and ρ strongly effect the stability as increasing ρ increases the chaotic regions, while adjusting F2 controls the balance between periodic and chaotic regimes.

Multistability

Multistability refers to the presence of multiple stable states or behaviours that a dynamical system can exhibit under the same set of system parameters. It shows that the system can settle into different long-term behaviours depending on its initial conditions. In a multistable system, different trajectories can lead to periodic, quasi-periodic, or chaotic outcomes, even though the system’s parameters remain unchanged. This phenomenon highlights how sensitive the system is to initial conditions, where small variations in starting points can result in vastly different dynamics55,56.

In practical terms, multistability is important because it indicates that the system can respond to perturbations or initial differences in a variety of ways, revealing complex underlying structures like attractors. It is commonly observed in systems like biological processes, climate dynamics, and mechanical systems, where different operational modes can coexist.

Figure 9 shows the multistability of the perturbed system (71) for fixed parameters ρ = 1.5 and τ = 4 and F1 = − 2, F2 = 1, evaluated at three different initial conditions: [0.15, − 0.1], [0.1, 0] and [− 0.2, 0.1]. The 2D phase portrait (a) clearly reveals that each initial condition evolves into a distinct trajectory. Although all remain bounded, the trajectories form non-overlapping attractor structures, implying the presence of multiple coexisting stable states. This is a key indicator of multistability, where the system does not converge to a single global attractor but instead settles into different long-term behaviours based on its starting state.

The time series plots in Fig. 9b reinforce this result. The evolution of F(\(\eta\)) and z(\(\eta\)) over time shows distinct waveform amplitudes and patterns for each initial condition, yet all remain in stable oscillatory regimes. The persistence of these differences throughout the entire simulation interval confirms that the divergence is not transient but an inherent feature of the system’s dynamics. This behavior highlights the sensitivity to initial conditions and emphasizes the nonlinear nature of the system, where small changes at the outset lead to qualitatively different yet stable outcomes.

Similarly, Fig. 10 illustrates multi-stability for the system with parameters ρ = 1.5, τ = 4, F1 = − 4 and F2 = − 3. The 2D phase portrait in Fig. 10a shows that different initial conditions lead to distinct yet overlapping trajectories, indicating coexisting attractors. In Fig. 10b, the time series plots show that each initial condition produces a unique oscillatory pattern in both F and z, confirming sustained differences and emphasizing sensitivity to initial states within a bounded regime.

Poincaré map

Poincaré map is a powerful technique used in the study of dynamical systems, especially for analyzing systems exhibiting periodic, quasi-periodic, or chaotic behaviour. It is named after the French mathematician Henri Poincaré, who made significant contributions to the study of celestial mechanics and dynamical systems. It helps in identifying periodicity, stability, or chaotic behaviour in systems57.

Figure 11a,b,c,d presents three Poincaré sections of the perturbed system (71), each corresponding to a different combination of the forcing amplitude ρ and τ, revealing how the system’s dynamics respond to varying external perturbation.

The Poincaré section in Fig. 11a for τ = 4 shows a complex, double-lobed structure with scattered points, indicating possible chaotic or quasi-periodic behavior.

In Fig. 11b for τ = 5, the map becomes a near-perfect closed loop, suggesting a transition to stable periodic motion.

In Fig. 11c at τ = 6, the shape slightly distorts but remains closed, implying persistence of bounded, non-chaotic dynamics.

The map in Fig. 11d when τ increases to 7 shows that the loop becomes more circular and regular, confirming strong periodicity and system stability.

The four Poincaré maps in Fig. 11 illustrate how varying the delay parameter τ influences system dynamics. As τ increases from 4 to 7, the system transitions from a more complex, possibly chaotic state (τ = 4) to highly regular, periodic behavior (τ = 7). This progression highlights that increasing τ stabilizes the dynamics, suppressing chaos and promoting structured, closed-loop trajectories characteristic of limit cycles or periodic orbits.

The overlaid Poincaré section for varying forcing frequencies τ = 4, 5, 6, 7 provides a clear visual comparison of the system’s long-term dynamical behavior under different periodic excitations58. Each colored loop represents a stroboscopic map that samples the system state at intervals synchronized with the respective forcing period. The resulting closed curves suggest that the system exhibits periodic or quasi-periodic behavior for all values of τ considered. Notably, the blue loop corresponding to τ = 4 appears more irregular and asymmetrical compared to the smoother, more circular loops observed for τ = 5, 6, 7, indicating that the system may undergo bifurcation or a change in attractor structure as τ decreases. This visualization highlights the system’s sensitivity to the external forcing frequency and captures how small changes in τ can lead to qualitatively distinct dynamical regimes, a key characteristic of nonlinear and potentially multistable or chaotic systems.

Lyapunov exponents

Lyapunov exponents serve as a tool to assess how sensitive a dynamical system is to its initial conditions. By evaluating how nearby trajectories in the system’s phase space either separate or come together over time, these exponents help identify chaotic behavior. A positive value suggests that small differences in initial conditions will grow rapidly, showing chaos, while a negative value indicates that trajectories are converging, pointing to stability. Overall, Lyapunov exponent analysis offers valuable understanding of the system’s stability, predictability, and long-term dynamics, especially in complex nonlinear systems59,60 (Fig. 12).

Figure 13 shows how the two largest Lyapunov exponents evolve over time for the given system. Initially, both exponents fluctuate before settling into stable values, λ1 converges to + 0.00477, while the λ2 settles near –0.00477. This indicates that the system shows low-dimensional chaotic behavior, as a positive Lyapunov exponent confirms sensitive dependence on initial conditions. The near symmetry of the exponents suggests that the system is close to volume-preserving, typical of Hamiltonian-like behavior. In contrast, a purely periodic system would have all Lyapunov exponents negative or zero, and a quasi-periodic system would show all zero exponents. Therefore, the presence of a small but positive Lyapunov exponent confirms mild yet persistent chaos in the dynamics.

Conclusion

In this study, the novel modified (G′/G2)-expansion method is effectively used to find new traveling wave solutions for the nonlinear coupled Riemann wave equation. This approach provides an efficient framework for constructing solutions to nonlinear fractional differential equations. Several soliton forms, including singular periodic and M-type solutions, are derived using Conformal, β and M-Truncated Derivatives. Our comparative analysis indicates that the β-Derivative yields more stable and reliable wave patterns, although all derivatives confirm the persistence of symmetric wave shapes with fractional parameter variation. Beyond the construction of analytical solutions, the study extends to the nonlinear dynamics of a Hamiltonian system using various bifurcation-based techniques. Phase portrait analysis reveals distinct energy landscapes, while bifurcation diagrams highlight transitions between stable and complex regimes influenced by changes in F2 and ρ. Sensitivity studies show the robustness of periodic behavior, and multistability investigations confirm the coexistence of multiple attractors depending on initial conditions. Poincaré maps and Lyapunov exponent calculations further uncover quasi-periodic and chaotic behavior, with evidence of low-dimensional chaos in selected parameter sets. These results not only validate the richness of the system’s nonlinear dynamics but also demonstrate the versatility of the combined analytical and numerical methodology. The study offers valuable insights applicable to nonlinear wave theory, chaotic systems, and engineering problems involving stability and transition dynamics.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Wazwaz, A. M. The variational iteration method for solving linear and nonlinear Volterra integral and integro-differential equations. Int. J. Comput. Math. 87(5), 1131–1141 (2010).

Losseva, T.V., Popel, S.I. & Golub’, A.P. Ion-acoustic solitons in dusty plasma. Plasma Phys. 38, 729–742 (2012).

Shah, N. A., Alyousef, H. A., El-Tantawy, S. A., Shah, R. & Chung, J. D. Analytical investigation of fractional-order Korteweg–De-Vries-type equations under Atangana–Baleanu–Caputo operator: Modeling nonlinear waves in a plasma and fluid. Symmetry 14(4), 739 (2022).

Arshed, S. Rahman, R.U., Raza, N., Khan, A.K. & Inc. M. A variety of fractional soliton solutions for three important coupled models arising in mathematical physics. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 36(01), (2022).

Arefin, M.A., Sadiya, U., Inc, M. & Uddin, M. H. Adequate soliton solutions to the space-time fractional telegraph equation and modified third-order KdV equation through a reliable technique. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54(5), 309 (2022).

Sadiya, U., Inc, M., Arefin, M. A. & Uddin, M. H. Consistent travelling waves solutions to the non-linear time fractional Klein-Gordon and Sine-Gordon equations through extended tanh-function approach. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 16(1), 594–607 (2022).

Zaman, U. H. M., Arefin, M. A., Akbar, M. A. & Uddin, M. H. Analyzing numerous travelling wave behavior to the fractional-order nonlinear Phi-4 and Allen–Cahn equations throughout a novel technique. Results Phys. 37, (2022).

Khatun, M. A., Arefin, M. A., Akbar, M. A. & Uddin, M. H. Numerous explicit soliton solutions to the fractional simplified Camassa–Holm equation through two reliable techniques. Ain Shams Eng. J. (2023).

Shakeel, M., Shah, N. A. & Chung, J. D. Novel analytical technique to find closed form solutions of time fractional partial differential equations. Fractal Fract. 6(1), (2022).

Khatun, M. A., Arefin, M. A., Uddin, M. H., İnç, M. & Akbar, M. A. An analytical approach to the solution of fractional-coupled modified equal width and fractional-coupled Burgers equations. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. (2022).

Zaman, U. H. M., Arefin, M. A., Akbar, M. A. & Uddin, M. H. Study of the soliton propagation of the fractional nonlinear type of evolution equation through a novel technique. PLoS one. 18(5), (2023).

Arefin, M. A., Khatun, M. A., Islam, M. S., Akbar, M. A. & Uddin, M. H. Explicit soliton solutions to the fractional order nonlinear models through the Atangana beta derivative. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 62(6), (2023).

Aljahdaly, N. H., Shah, R., Naeem, M. & Arefin, M. A. A comparative analysis of fractional space-time advection-dispersion equation via semi-analytical methods. J. Funct. Spaces. 2022, (2022).

Qureshi, S., Chang, M. M. & Shaikh. A. A. Analysis of series RL and RC circuits with time-invariant source using truncated M, Atangana beta and conformable derivatives. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 6(3), 217–227 (2021).

Shah, N. A. et al. A comparative analysis of fractional-order Kaup-Kupershmidt equation within different operators. Symmetry. 14(5), 986 (2022).

Singh, R., Mishra, J. & Gupta, V. K. Dynamical analysis of a tumor growth model under the effect of fractal fractional Caputo-Fabrizio derivative. Int. J. Math. Comput. Eng. 1(1), 115–126 (2023).

Ortigueira, M. D. & Machado, J. T. What is a fractional derivative?. J. Comput. Phys. 293, 4–13 (2015).

Atangana, A. & Gómez-Aguilar, J. F. Numerical approximation of Riemann definition of fractional derivative: From Riemann to Atangana. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 34, 1502–1523 (2018).

Jumarie, G. Modified Riemann-Liouville derivative and fractional Taylor series of non-differentiable functions: further results. Comput. Appl. Math. 51(9–10), 1367–1376 (2006).

Shakeel, M., Ul-Hassan, Q. M., Ahmad, J. & Naqvi, T. Exact solutions of the time fractional BBM-Burger equation by novel (G′/G)-expansion method. Adv. Math. Phys. 2014, 15 (2014).

Atangana, A. & Koca, I. Chaos in a simple nonlinear system with Atangana-Baleanu derivatives with fractional order. Chaos Solitons Fractal. 89, 447–454 (2016).

Sene, N. Second-grade fluid model with Caputo–Liouville generalized fractional derivative. Chaos Solitons Fract. 133, (2020).

Yépez-Martínez, H., Inc, M. & Rezazadeh, H. New analytical solutions by the application of the modified double sub-equation method to the (1 + 1)-Schamel-KdV equation, the Gardner equation and the Burgers equation. Phys. Scr. 97(8), (2022).

Ullah, A., Shakeel, M., Ahmad, B., Shah, N. A. & Chung, J. D. Solitons solution of Riemann wave equation via modified Exp function method. Symmetry. 14(12), (2022).

Zhang, S. A generalized new auxiliary equation method and its application to the (2 + 1)-dimensional breaking soliton equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 190(1), 510–516 (2007).

Ghanbari, B. & Inc, M. A new generalized exponential rational function method to find exact special solutions for the resonance nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 133(142), (2018).

Zafar, A., Shakeel, M. & Ali, A., Rezazadeh, H., Bekir, A. Analytical study of complex Ginzburg–Landau equation arising in nonlinear optics. J. Nonlinear Opt. Phys. Mater. 32(1), (2023).

Shakeel, M. & Mohyud-Din, S. T. Soliton solutions for the positive Gardner-KP equation by (G′/G, 1/G) – expansion method. Ain Shams Eng. J. 5(3), 951–958 (2014).

Taşcan, F. & Bekir, A. Analytic solutions of the (2 + 1)-dimensional nonlinear evolution equations using the sine–cosine method. Appl. Math. Comput. 215(8), 3134–3139 (2009).

Jaradat, I. & Alquran, M. Geometric perspectives of the two-mode upgrade of a generalized Fisher–Burgers equation that governs the propagation of two simultaneously moving waves. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 404, (2022).

Jaradat, I., Alquran, M., Ali, M. A numerical study on weak-dissipative two-mode perturbed Burgers’ and Ostrovsky models: right-left moving waves. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 133(164), (2018).

Alquran, M., Jaradat, I., Yusuf, A. & Sulaiman, T. A. Heart-cusp and bell-shaped-cusp optical solitons for an extended two-mode version of the complex Hirota model: Application in optics. Opt. Quant. Electron. 53(1), (2021).

Jaradat, I. & Alquran, M. Construction of solitary two-wave solutions for a new two-mode version of the Zakharov-Kuznetsov equation. Mathematics. 8(7), (2020).

Shakeel, M., Bibi, A., Zafar, A. & Sohail, M. Solitary wave solutions of Camassa–Holm and Degasperis–Procesi equations with Atangana’s conformable derivative. Comput. Appl. Math. 42(101), (2023).

Li, W. A., Hao, C. & Guo-Cai, Z. The (w/g)-expansion method and its application to Vakhnenko equation. Chin. Phys. B. 18(2), (2009).

Gepreel, K. A. Exact solutions for nonlinear integral member of Kadomtsev-Petviashvili hierarchy differential equations using the modified (w/g)-expansion method. Comput. Math. Appl. 72(9), 2072–2083 (2016).

Aljahdaly, N. H. Some applications of the modified (G′/G2)-expansion method in mathematical physics. Results Phys. 13, (2019).

Mumtaz, A., Shakeel, M., Alshehri, M. & Shah, N. A. New analytical technique for prototype closed form solutions of certain nonlinear partial differential equations. Results Phys. 60, 107640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2024.107640 (2024).

Ansar, R., Abbas, M., Mohammed, P. O., Al-Sarairah, E., Gepreel, K, A. & Soliman, M. S. Dynamical study of coupled Riemann wave equation involving conformable, beta, and M-truncated derivatives via two efficient analytical methods. Symmetry. 15(7), 1293 (2023).

Saboor, A., Shakeel, M., Liu, X., Zafar, A. & Ashraf, M. A comparative study of two fractional nonlinear optical models via modified (G′/G2)-expansion method. Opt. Quan. Electron. 56(259), (2024).

Hosseini, K., Hinçal, E. & Ilie, M. Bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors, sensitivity analysis, and soliton solutions of a generalized Schrödinger equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 111(18), 17455–17462 (2023).

Jhangeer, A., Ansari, A. R., Imran, M. & Riaz, M. B. Comparative study of mathematical models in applied sciences. AIMS Math. 9(7), 18013–18033 (2024).

Khalil, R., Al Horani, M., Yousef, A. & Sababheh, M. A new definition of fractional derivative. Comput. Appl. Math. 264, 65–70 (2014).

Hussain, A., Jhangeer, A., Abbas, N., Khan, I. & Sherif, E. S. M. Optical solitons of fractional complex Ginzburg-Landau equation with conformable, beta, and M-truncated derivatives: A comparative study. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 1–19 (2020).

Sousa, J. V. D. C. & de-Oliveira, E. C. A new truncated M-fractional derivative type unifying some fractional derivative types with classical properties. Int. J. Anal. Appl. (2017).

Shahen, N. H. M., Bashar, M. H. & Ali, M. S. Dynamical analysis of long-wave phenomena for the nonlinear conformable space-time fractional (2 + 1)-dimensional AKNS equation in water wave mechanics. Heliyon. 6(10), (2020).

Chow, S. N. & Hale, J. K. Methods of Bifurcation Theory (Springer, 2012).

Mokni, K., Thirthar, A. A., Ch-Chaoui, M., Jawad, S. & Aqib, M. Stability and bifurcation analysis in a novel discrete prey-predator system incorporating moonlight, water availability, and vigilance effects. Int. J. Dynam. Control. 13, 219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-025-01718-2 (2025).

Jhangeer, A., Almusawa, H. & Hussain, Z. Bifurcation study and pattern formation analysis of a nonlinear dynamical system for chaotic behavior in travelling wave solution. Results Phys. 37, 105492 (2022).

Thirthar, A. A., Alaoui, A. L., Roy, S. & Tiwari, P. K. Fractional and stochastic dynamics of predator–prey systems: The role of fear and global warming. Eur. Phys. J. B. 98, 147. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/s10051-025-00992-5 (2025).

Wu, X. H., Gao, Y. T., Yu, X. & Liu, F. Y. Generalized Darboux transformation and solitons for a Kraenkel–Manna–Merle system in a ferromagnetic saturator. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 14421–14433 (2023).

Ganie, A. H., Rahaman, M. S., Aladsani, F. A. & Ullah, M. S. Bifurcation, chaos, and soliton analysis of the Manakov equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 9807–9821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-024-10829-y (2025).

Riaz, M. B., Jhangeer, A., Duraihem, F. Z. & Martin, J. Analyzing dynamics: Lie symmetry approach to bifurcation, chaos, multistability, and solitons in extended (3 + 1)-dimensional wave equation. Symmetry. 16(5), https://doi.org/10.3390/sym16050608 (2024).

Ullah, M. S., Ali, M. Z. & Roshid, H. O. Stability analysis, model expansion method, and diverse chaos-detecting tools for the DSKP model. Sci. Rep. 15, 13658. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98275-7 (2025).

Jhangeer, A. & Faridi, W. A., Alshehri, M. The study of phase portraits, multistability visualization, Lyapunov exponents and chaos identification of coupled nonlinear volatility and option pricing model. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 139, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/s13360-024-05435-1 (2024).

Jhangeer, A., Ansari, A. R., Rahimzai, A. A., Beenish & Khan, A. Q. Exploring chaos and sensitivity in the Ivancevic option pricing model through perturbation analysis. PLoS One. 19, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0312805 (2024).

Jhangeer, A., Riaz, M. B. & Kazmi, S. S. Analysis of chaotic dynamics and Poincaré maps in nonlinear systems. Chaos Solitons Fract. 150, 111234 (2021).

Gritli, H. Poincaré maps design for the stabilization of limit cycles in non-autonomous nonlinear systems via time-piecewise-constant feedback controllers with application to the chaotic Duffing oscillator. Chaos Solitons Fract. 127, 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2019.06.035 (2019).

Wolf, A., Swift, J. B., Swinney, H. L. & Vastano, J. A. Determining Lyapunov exponents from a time series. Phys. D. 16, 285–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2789(85)90011-9 (1985).

Abdalla, M., Roshid, Md., Ullah, M. S. & Hossain, I. Dynamical analysis, and the effect of fractional parameters on optical soliton solution for Yajima–Oikawa model in short-wave and long-wave. Chaos Solitons Fract. 199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2025.116697 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and N.A.S.; Methodology, K.M. and N.A.S.; Software, A.M. and M.S.; Validation, A.M. and N.A.S.; Formal analysis, A.M. K.M. and M.S.; Resources, A.M. and M.S.; Writing—original draft, A.M. and N.A.S.; Writing—review and editing, K.M. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Amna Mumtaz and Nehad Ali Shah contributed equally to this work and are co-first authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The entire work is the original work of the authors.

Consent for publication

All the authors have given their consent to publish the paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mumtaz, A., Masood, K., Shakeel, M. et al. Exploring complex dynamics in nonlinear Riemann wave models using fractional calculus-based expansion. Sci Rep 15, 43559 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30414-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30414-6