Abstract

To evaluate the effectiveness of construction schemes for cement-stabilized macadam bases, this study focuses on the impact of construction vehicle loads on the base’s mechanical response. First, the physical properties of raw materials and the early-age mechanical parameters of the mixture were obtained through laboratory tests. Subsequently, an orthogonal experimental design was adopted, and KENPAVE software was used to calculate the maximum tensile stress at the bottom of the base under various construction loads. Range analysis was conducted to clarify the degree of influence of factors such as pavement structure thickness, material modulus, and construction scheme on tensile stress. The study ultimately identified a structural combination with optimal bearing capacity and revealed stress variation patterns under different loads. The results indicate that a continuous construction scheme is superior to an intermittent scheme in controlling early-age tensile stress in the base, which is more beneficial for ensuring long-term pavement performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of global infrastructure, constructing pavement systems with high load-bearing capacity and durability has become a primary focus in modern transportation networks. Cement-stabilized macadam bases, known for their low cost, high early strength, and excellent stability, are extensively utilized in pavement base construction and play a pivotal role in ensuring the load-bearing capacity and long-term performance of asphalt pavements1,2. However, in recent years, the bases have encountered challenges due to increasing traffic volumes and axle loads during their service life. Such challenges significantly affect the stress distribution and deformation resistance of the entire pavement system, accelerating structural deterioration, diminishing load-bearing capacity, and ultimately reducing pavement service life. Ensuring high construction quality for cement-stabilized macadam bases is crucial for enhancing the load-bearing capacity of pavement structure3,4,5. Moreover, the rationality of construction schemes for these bases directly influences construction quality, underscoring the necessity of determining reasonable construction schemes6,7.

In highway design, the thickness of cement-stabilized macadam bases is typically designed to exceed 30 cm. During construction, it is usually paved and compacted in two layers, each no thicker than 20 cm8. According to the current “Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Pavement Bases”9, cement-stabilized macadam bases can be constructed using either layered discontinuous construction or layered continuous construction. The former represents a traditional method, while the latter is a relatively new approach inspired by the continuous paving techniques used for asphalt surfaces. Both methods have distinct advantages and disadvantages. For the relatively new layered continuous construction method, Ding et al.10 conducted laboratory interlayer bonding tests, on-site smoothness tests, and compaction tests to verify the interlayer bonding state during continuous paving. They proposed smoothness control standards, compaction procedures, and the optimal interval time for double-layer continuous paving, providing a theoretical basis for addressing quality control issues in such paving. Jun et al.11 analyzed the effects of layering time intervals, interlayer contamination, and compaction energy on the compressive and interlayer shear strength of cement-stabilized macadam. Wang et al.12 optimized the selection of construction machinery for thick cement-stabilized macadam bases under layered continuous paving, developed rational paving and compaction procedures, and evaluated the economic benefits of this technique. Fang et al.13 investigated the plastic deformation patterns of subbases under thick continuous paving and proposed smoothness control standards for the construction of thick bases using this approach. Ping et al.14 introduced quality control technologies for double-layer continuous paving, analyzed the construction characteristics, and developed relevant quality control strategies. Yang, Qiao and Huang15,16,17 analyzed the double-layer continuous paving construction process of cement-stabilized macadam base. They focused on elaborating the construction techniques of double-layer continuous paving, developed a construction network diagram for the process, and successfully applied it in on-site construction.

To date, numerous scholars have conducted comparative studies on the two construction methods. Zhang et al.18 compared the mechanical properties of base mixtures laid using continuous and discontinuous paving methods. Their findings indicate that, under identical curing times and test temperatures, continuous paving significantly enhances the mechanical properties of the base, particularly in terms of shear and flexural strength. Li et al.19 analyzed the impact of vehicular loads on the stress characteristics of pavement structures during the formation of overall structural strength under varying curing temperatures, comparing the layered and continuous paving methods. Their research provides a foundation for selecting appropriate base construction methods under different curing conditions. Qing et al.20 performed an economic analysis of maintenance costs by integrating traditional layered paving techniques with the layered continuous paving method for constructing cement-stabilized macadam bases. They estimated the costs of preventive maintenance and damage treatment at various stages, concluding that the layered continuous paving technique reduces maintenance costs during the maintenance phase. At present, research on the rationality of construction schemes for cement-stabilized macadam bases mainly focuses on construction processes and smoothness control, as well as the analysis of pavement performance and economic benefits after construction. Limited research has been conducted on the impact of vehicular loads during construction on the mechanical response of the base, with most studies concentrating on the effect of single factors on the mechanical response. For instance, Ma21 calculated the tensile stress at the bottom of cement-stabilized macadam layers caused by vehicular loads at different curing ages. In addition, a single-variable method was used to systematically analyze the effects of pavement structural layer thickness, material compressive resilient modulus, vehicular load, and construction schemes on the maximum tensile stress at the layer bottom. However, the influence of multiple factors on the maximum tensile stress at the layer bottom has not been adequately analyzed.

To determine an optimal construction scheme, this study investigates the impact of construction vehicle loads on the maximum tensile stress at the bottom of cement-stabilized macadam bases. The early-age mechanical properties of the materials were first obtained through laboratory testing and used as inputs for an orthogonal experimental design. The KENPAVE software was then employed to calculate the tensile stress under various conditions. Range analysis was conducted to quantify the influence of key factors, including pavement layer thickness, material modulus, and construction scheme. Finally, the calculated tensile stress was compared against the material’s splitting tensile strength to assess the risk of flexural-tensile failure, thereby identifying the most effective construction method and structural design.

Materials and methods

To ensure that the cement-stabilized macadam meets the specifications and to obtain the material parameters required by the software, the physicochemical properties of the selected raw materials and the mechanical properties of the cement-stabilized macadam are tested.

Materials

The materials used in the tests included cement, fly ash, and aggregate. In this study, ordinary 325# slag silicate cement was selected, and its performance indexes are shown in Table 1. The measured chemical composition of the selected fly ash is presented in Table 2. The technical indicators of the selected aggregates are provided in Tables 3 and 4.

The strength and deformation characteristics of cement-stabilized granules are closely related to their material composition. In asphalt pavement, the base is subjected to significant load pressure. “Specifications for Design of Highway Asphalt Pavement”22 stipulates that: when used on expressways and first-class highways, the cement-stabilized granule base must achieve a seven-day compressive strength of 3.0–5.0 MPa. To attain such high early strength, the particle composition must meet specific grading requirements and fully utilize the skeleton role of the particles. Based on this, the grading of water-stabilized gravel is shown in Table 5, and its grading curve is presented in Fig. 1.

While the strength of cement-stabilized granules is roughly proportional to the cement dosage, higher dosages present a trade-off. The increased stiffness resulting from cement hydration makes the material highly susceptible to dry shrinkage cracking. Established research indicates that a cement dosage between 4 and 6% minimizes shrinkage, whereas dosages exceeding 7% can cause significant cracking. Based on these findings, this study selected cement dosages of 4%, 5%, and 6% for the experiments, denoted as CM-4, CM-5, and CM-6 respectively.

In accordance with the requirements specified in “Test Methods for Inorganic Binder Stabilized Materials in Highway Engineering”23 and “Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Pavement Base Courses”24, cylindrical specimens with a uniform diameter and height of 50 mm were prepared in this study. The compaction degree was controlled at 98%, which refers to the standard requirement of 98% for cement-stabilized base courses of expressways and first-class highways. Thirteen specimens were prepared for each group, all specimens were cured under standard conditions for 7 days, 14 days, and 28 days respectively, and subjected to water saturation soaking treatment on the last day of curing. The entire process of specimen preparation and curing is illustrated in Fig. 2.

The pavement performance of cement-stabilized macadam

Upon completion of curing, the specimens were taken out, and their unconfined compressive strength, splitting strength, and compressive resilient modulus were determined in accordance with the relevant provisions of the “Test Methods for Inorganic Binder Stabilized Materials in Highway Engineering”25 using the corresponding specific test methods. Specifically, the unconfined compressive strength test was conducted following the “Test Method for Unconfined Compressive Strength of Inorganic Binder Stabilized Materials” (T 0805-2024); the splitting strength test adhered to the “Test Method for Splitting Strength of Inorganic Binder Stabilized Materials” (T 0806-1994); and the compressive resilient modulus test (Top Surface Method) was performed in accordance with the “Test Method for Laboratory Compressive Resilient Modulus of Inorganic Binder Stabilized Materials” (T 0808-1994).All tests were conducted using 50 mm × 50 mm cylindrical specimens, all mechanical tests were conducted on a WAW-300 hydraulic servo universal testing machine equipped with a corresponding control system, with the specific test protocol as follows: (1) Unconfined compressive strength test: The measurement accuracy of unconfined compressive strength is ± 1%, and the loading rate was maintained at 1mm/min; (2) Splitting strength test: The measurement accuracy of Splitting strength is ± 1%. During the test, the deformation of the specimens was increased at a constant rate, and the loading rate was kept at 1mm/min; (3) Compressive resilient modulus (Top Surface Method): A preloading force of 0.3p (where p is the unconfined compressive strength of the specimen) was applied to the specimens and maintained for 30 s. Subsequently, the predetermined unit pressure was divided into 5 equal increments, and loading was conducted from low pressure to high pressure. The displacement readings of the indenter were recorded both before and after each loading cycle, and this operation was repeated until the resilient deformation recording for the final unit pressure increment was completed. The test instruments and procedures for the three tests are presented in Fig. 3.

Analysis of test results

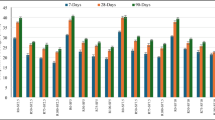

The curves showing the changes in unconfined compressive strength, splitting strength, and compressive resilient modulus of cement-stabilized macadam under different cement dosages and curing ages are presented in Fig. 4.

As can be seen from Fig. 4, the unconfined compressive strength, splitting strength, and compressive resilient modulus of cement-stabilized macadam show similar variation trends with cement dosage and curing age—all increasing as cement dosage rises and curing age extends. Additionally, across all groups and different cement dosages, the strength and modulus grow rapidly in the early stage (7 d–14 d), while the growth trend slows down in the later stage (14 d- 28 d). By day 28, the changes in various mechanical property indicators basically tend to stabilize26,27,28. To explore the stability and uniformity of its mechanical property development, further analysis was conducted on the test results in Tables 6, 7, and 8, the representative value refers to the characteristic value that can represent the mechanical properties of this group of cement-stabilized macadam under the condition of a 95% guarantee rate.

As can be seen from Tables 6, 7, and 8, the representative value range of unconfined compressive strength is approximately 5.0–7.5 MPa, that of splitting strength is about 0.15–0.6 MPa, and that of compressive resilient modulus is roughly 1500–3500 MPa. This indicates that cement-stabilized macadam can meet the road performance requirements of different stages under appropriate cement dosage and curing age conditions. Further variability analysis was conducted on the test results of unconfined compressive strength, splitting strength, and compressive resilient modulus from the two dimensions of cement dosage and curing age:

From the dimension of cement dosage, as the cement dosage increases from 4 to 6%, the coefficient of variation of the three mechanical property indicators shows a significant downward trend in most cases. This indicates that increasing the cement dosage can effectively improve the uniformity of the material’s mechanical properties. As a cementitious material, a higher cement dosage means more cement paste can wrap and bond aggregates more fully, reducing performance dispersion caused by insufficient local bonding or uneven particle distribution, and making the material structure denser and performance more stable.

From the dimension of curing age, in the early stage (7d–14d), the variability of each mechanical property indicator of cement-stabilized macadam material behaves differently. The coefficient of variation of unconfined compressive strength remains stable or increases slightly under different cement dosages, indicating that there may be differences in the rate of early rapid hydration among different specimens; the coefficient of variation of splitting strength and resilient modulus mostly decreases, which shows that with the progress of curing, the structural strength develops effectively and uniformly. In the later stage (14d–28d), the coefficient of variation of unconfined compressive strength remains stable, indicating that strength growth enters a stable period with good uniformity; the coefficient of variation of splitting strength increases in the low-dosage group (CM-4). The reason may be that under low dosage, the slight inhomogeneity of early hydration leads to increased dispersion in the later stage, while the coefficient of variation of the high-dosage groups (CM-5, CM-6) remains stable or decreases. This indicates that curing age plays an important role in the development of crack resistance strength29,30.

To sum up, the coefficient of variation of unconfined compressive strength is the smallest (0.04–0.07), indicating that this property is the most stable and the test results are the most reliable; the coefficient of variation of splitting strength is the largest, which can reach 0.2 under low cement dosage and long curing age, showing that this property is more sensitive to internal microcracks and defects of the material, with relatively high dispersion; the coefficient of variation of compressive resilient modulus is between the two, but may fluctuate greatly in the early stage, that is, the modulus performance of cement-stabilized macadam has certain uncertainty when it is not fully cured. This indicates that increasing the cement dosage is an effective way to control the material’s variability and ensure the uniformity and stability of its mechanical properties. Cement-stabilized macadam with high dosage (CM-6) not only achieves higher strength but also exhibits better uniformity and reliability. The influence of curing age on the uniformity of mechanical properties of cement-stabilized macadam is closely related to the cement dosage. An appropriate cement dosage can effectively offset the risk of performance dispersion under long age, while for low-dosage materials, more attention should be paid to the dispersion of their long-term performance. From the perspective of engineering design and quality control, unconfined compressive strength can be used as the most representative core evaluation index due to its smallest dispersion; for indicators with large dispersion such as splitting strength, a higher guarantee rate should be considered or stricter quality control measures should be implemented when determining their values.

Structure and material parameters of cement-stabilized macadam base

This study employed the KENPAVE pavement analysis software for structural calculations, the pavement geometric model used in the analysis is shown in Fig. 5. Considering that pavements generally exhibit small deformation under vehicle loads, with insignificant material nonlinear characteristics, and to align with mainstream pavement design specifications while shortening the calculation time of KENPAVE software, the software adopts the elastic constitutive assumption for materials of each structural layer. However, this assumption fails to reflect the cumulative damage of materials under long-term loads and also struggles to capture the viscoelastic deformation characteristics of materials in high-temperature environments. Based on its prevalence in Chinese engineering practice, a double-layer cement-stabilized macadam base structure was selected for the analysis. The required material parameters for the model, corresponding to different curing ages, were derived from the experimental tests described in Section “The pavement performance of cement-stabilized macadam”, as shown in Table 9.

To understand the actual load of construction vehicles, the author conducted a special investigation on the axle loads of such vehicles. Through weighing, it was found that the actual loads of some construction vehicles, including freight trucks and engineering sprinklers, significantly exceeded the standard axle load of 100KN used in the road structure design, indicating a serious overload condition. In this study, the maximum total weight of construction vehicles and cargo was 54 t, the minimum was 18 t, the maximum load of a single axle was 18 t, the minimum was 6 t, and the rear axle consisted of a two-axle, two-wheel set.

With a standard axle load of 100KN for the double wheel set, the radius of the equivalent circle for the double circular uniform vertical load is 10.65 cm, and the center distance remains unchanged at 31.95 cm under this load. As axle load increases, both wheel pressure and the contact area with the ground also increase. This paper employs Belgium’s empirical formula for axle load and ground area, as well as the following formula (1), to calculate the area of the equivalent circle for different coaxial loads, based on the current axle load conditions31,32. The load application diagram of the Belgian Method is shown in Fig. 6, the axle load calculation parameters are shown in Table 10.

where A represents the ground area of the tire (cm2) and P represents the tire pressure (N).

Results and discussion

Research on the rationality of sub-base and base discontinuous construction

The design parameters of each structural layer, such as the sub-base and base layers, significantly influence the tensile stress induced by the construction vehicle load. To identify general trends and simplify the calculation process, the orthogonal design method is employed to investigate the impact of each factor on the calculation index. The L25 (5–3) orthogonal test is constructed by selecting the thickness of the sub-base, the modulus of the sub-base, and the modulus of the soil foundation as the factors for the orthogonal test. Each factor is set at five levels, with the range of each level encompassing the values of common materials, and the numerical growth rate of each factor at the corresponding level remaining relatively consistent. Table 11 presents the orthogonal experimental factor level table for the base laid after 7 and 14 days of sub-base curing under discontinuous construction conditions.

The orthogonal experimental design arrangement and calculation results are presented in Table 12. The results from Table 12 indicate that, in 25 groups of orthogonal experiments, the minimum tensile stress at the bottom of the sub-base layer after 7 days of curing reaches 0.742 MPa, significantly exceeding the maximum splitting strength of cement-treated macadam material at 7 days, which is 0.35 MPa. The minimum tensile stress at the bottom of the sub-base layer reaches 0.879 MPa after 14 days of curing, also surpassing the maximum splitting strength of cement-treated macadam material at 14 days, which is 0.48 MPa. Therefore, when a construction vehicle with an axle load of 180KN is used, the base will experience flexural-tensile failure.

To investigate measures to prevent flexural-tensile failure of cement-stabilized macadam sub-base, the maximum tensile stress at the bottom of the sub-base layer was analyzed using data from 7 days of curing. The results are presented in Table 13. Through range analysis, the influence of each factor level on the investigation index can be observed. A larger range difference indicates a greater impact on the index when the factors change. In the horizontal range of the factors, the sensitivity of the three parameters affecting the tensile stress of the sub-base layer is as follows: modulus of the subgrade layer > thickness of the sub-base layer > modulus of the sub-base layer. This indicates that the subgrade modulus has the greatest influence on the bottom tensile stress of the sub-base layer.

Based on Table 13, a graphical analysis of the influence of various factors on the tensile stress at the bottom of the subbase after 7 days of curing can be derived, as shown in Fig. 7. The figure indicates that the tensile stress at the bottom of the sub-base decreases with an increase in subbase thickness and subgrade soil modulus. Meanwhile, the tensile stress initially increases and then shows a decreasing trend with an increase in the subbase modulus.

This analysis evaluates the bearing capacity of the optimal pavement structure after 7 days of curing,as shown in Fig. 8. The results indicate a direct proportional relationship between the construction vehicle’s axle load and the maximum tensile stress at the base bottom. Calculations show that an axle load of 90 KN induces a tensile stress that exceeds the material’s 7-day splitting strength, leading to flexural-tensile failure. This implies that vehicle loads must be restricted to below 90 KN. However, such a limitation is impractical, as it leads to significant underutilization of standard construction machinery. Moreover, for structures on weaker soil foundations (e.g., 40 MPa), the maximum allowable axle load drops to an unfeasible 50 KN. Therefore, from a mechanical perspective, the discontinuous construction scheme, which requires paving on the base after a 7-day curing period, is not a viable option.

Similarly, through the analysis of the influence of each factor on the tensile stress at the bottom of the layer after 14 days of curing of the sub-base, it is found that the axle load of the construction vehicle paving the base layer should be controlled to re-main below 60 KN. This is because the rate of increase in tensile stress at the bottom of the layer, caused by changes in the unconfined compressive rebound modulus of the cement-stabilized macadam, is greater than the rate of increase in splitting strength. Therefore, when the sub-base is paved 14 days after curing, it will similarly cause damage to the sub-base. It can be concluded that the discontinuous construction scheme for the sub-base and base is unreasonable.

Research on the rationality of continuous construction of sub-base and base layer

This study evaluates a continuous construction method, where the combined base and sub-base are cured before the surface layer is paved. Using an L25 orthogonal design, the maximum tensile stress was calculated under a 180 KN axle load for curing periods of 7 and 14 days, the results are shown in Table 14.

After 7 days of curing, the maximum tensile stress in the base layer was only 0.128 MPa, far below the material’s splitting strength, indicating no risk of damage. However, the sub-base was highly vulnerable, with only 4 of the 25 structural combinations preventing flexural-tensile failure.

By extending the curing period to 14 days, the base layer remained safe (max stress of 0.132 MPa). More importantly, the probability of the sub-base stress remaining within the material’s strength limits increased significantly to 48%. This demonstrates that prolonging the curing time is critical for reducing the risk of failure in the sub-base layer under heavy construction loads.

The maximum tensile stress at the bottom of the sub-base layer was analyzed using polar analysis based on data from 7 days of curing. The results are shown in Table 15. The extreme variance analysis in Table 15 shows that, as the factors vary within their respective level ranges, the sensitivity of the five calculated parameters affecting the tensile stress at the base of the sub-base layer follows this descending order: sub-grade modulus > sub-base thickness > base thickness > sub-base modulus > base mod-ulus. This indicates that the subgrade modulus has the greatest influence on the tensile stress at the base of the sub-base layer.

From Table 15, an intuitive analysis chart of the effects of various factors on the tensile stress at the bottom of the subbase after 7 days of curing can be generated, as shown in Fig. 9. The figure reveals that the tensile stress at the bottom of the sub-base after 7 days of curing decreases overall with the increase in the thickness of the base and subbase layers, as well as the modulus of the base layer and subgrade soil, while it increases with the rise in the modulus of the subbase layer.

The variation of the maximum tensile stress of each layer with the load is shown in Fig. 10, an analysis of load effects shows that as the construction vehicle’s axle load increases, the maximum tensile stress at the bottom of both the base and sub-base layers rises. This increase is significantly more rapid in the sub-base layer than in the base layer, making the sub-base more sensitive to load variations. Crucially, for the continuous construction scheme, the base layer will not experience flexural-tensile failure as long as the vehicle axle load is kept below 180 KN. This demonstrates that reducing the vehicle load is an effective way to protect the integrity of the sub-base. These findings confirm that, from a mechanical perspective, the continuous construction scheme is more reasonable and robust than the discontinuous scheme.

Pavement engineering application recommendations

Prioritizing the avoidance of discontinuous construction schemes

It is shown through orthogonal testing and mechanical analysis that discontinuous construction schemes for cement-stabilized macadam base courses—wherein paving follows a 7- or 14-day subbase curing period—inherently carry a risk of flexural-tensile failure. Consequently, it is recommended to prioritize continuous construction to mitigate disturbances imposed on the subbase by subsequent construction operations. In cases where discontinuous construction is unavoidable, two principal measures must be adopted: firstly, stringent control of construction vehicle axle loads, enforcing limits below 90 KN after 7 days and below 60 KN after 14 days of curing, complemented by pre-verification of machinery axle loads to preclude overloading; and secondly, risk mitigation through adjustment of critical parameters influencing subbase tensile stress, namely by increasing subbase thickness and ensuring a rational modulus match.

Using the continuous construction scheme

-

(1)

Extending the curing period

After 7 days of curing, only 4 out of 25 structural combinations can avoid flexural-tensile failure of the subbase. When the curing period is extended to 14 days, the probability that the subbase stress meets the material strength requirements increases to 48%, and the base course remains safe (the maximum tensile stress is 0.128 MPa at 7 days and 0.132 MPa at 14 days, both far lower than the material’s splitting strength). A 14-day curing period is therefore recommended as the priority.

-

(2)

Optimizing structural parameters

Analysis indicates that the tensile stress at the subbase bottom increases with the rise of subbase modulus, and according to the range analysis of 7-day curing data—with parameter sensitivity ranked as subgrade modulus > subbase thickness > base course thickness > subbase modulus > base course modulus—the tensile stress at the subbase bottom can be reduced by improving the subgrade modulus, increasing the structural layer thickness, and reasonably controlling the subbase modulus; this approach not only ensures that structural strength requirements are met, but also increases the base course modulus and ensures its compatibility with the subbase modulus, thereby forming a sound stress transfer system to reduce the stress burden on the subbase.

-

(3)

Controlling construction loads and processes

The axle load of construction vehicles must be controlled within 180 KN to prevent flexural-tensile failure of the base course, and since the subbase is more sensitive to loads, the rate of tensile stress increase in the subbase is much faster than that in the base course when the axle load increases, so overloaded vehicles must be strictly prohibited from entering the construction area; meanwhile, it is necessary to strengthen monitoring during the curing period and before construction—ensuring stable curing conditions during the curing period to avoid interruptions, testing the actual strength of the base course, subbase, and subgrade modulus before construction, and proceeding with surface course paving only after confirming that all indicators meet the design requirements—and for continuous construction, plan material supply and equipment scheduling in advance to ensure construction continuity, which avoids poor bonding between structural layers or curing cycle disorders caused by construction interruptions.

Engineering implications and quality control

Based on the mechanical property test results of cement-stabilized macadam, the cement-stabilized macadam with high cement dosage (CM-6) not only achieves higher strength but also exhibits better uniformity and reliability. Furthermore, a longer curing period allows for a more complete cement hydration reaction. Hydration products continuously fill the gaps between aggregates, enhance the bonding strength among particles, and effectively compensate for potential local cementation unevenness during the early hydration stage. This helps offset the risk of performance dispersion (e.g., due to environmental factors) over extended curing periods, ensuring the overall uniformity of the material remains stable at all times. Consequently, mix design must adequately account for the synergistic effect between the curing period and cement dosage. Especially for structural layers with low cement dosage, focused efforts should be made to prevent and control the risk of long-term performance dispersion. In addition, it is recommended to use unconfined compressive strength as the core evaluation index; for parameters with relatively high dispersion such as splitting strength, acceptance work should be carried out using a higher guarantee rate or more stringent control standards.

Conclusions

This study evaluated different construction schemes for cement-stabilized macadam bases by using KENPAVE software and an orthogonal test design to analyze tensile stresses induced by construction vehicle loads. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The strength and modulus of the cement-stabilized macadam improve with increased curing age and cement dosage. This growth is rapid in the early stages and slows over time.

-

(2)

The discontinuous construction method, where the base is paved on a previously cured sub-base, consistently leads to sub-base failure. After 7 days of curing, the maximum calculated tensile stress (0.742 MPa) far exceeds the material’s splitting strength (0.35 MPa). Similarly, after 14 days, the maximum stress (0.879 MPa) also greatly exceeds the material’s strength (0.48 MPa). In this scheme, restricting vehicle loads is not a practical solution to prevent failure.

-

(3)

In the continuous construction method, where the base and sub-base are paved together before curing, performance is significantly better. After 7 days of curing, the base layer is safe with a maximum stress of 0.128 MPa, but the sub-base remains at high risk, as only 4 of 25 combinations avoid failure. Extending the curing period to 14 days keeps the base layer undamaged and increases the sub-base’s probability of avoiding failure to 48%.

-

(4)

These findings indicate that continuous construction is the preferable method. Furthermore, unlike the discontinuous approach, limiting construction vehicle loads in a continuous scheme is a viable strategy to further reduce the likelihood of damage to the sub-base layer.

Data availability

The datasets generated during analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Islam, M. M. U., Li, J., Roychand, R., Saberian, M. & Chen, F. A comprehensive review on the application of renewable waste tire rubbers and fibers in sustainable concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 374, 133998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133998 (2022).

Tang, K., Mao, X. S., Wu, Q., Zhang, J. X. & Huang, W. J. Influence of temperature and sodium sulfate content on the compaction characteristics of cement-stabilized macadam base materials. Materials 13(16), 3610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13163610 (2020).

Qin, Y., Meng, Y., Lu, Z., Zhao, Q. & Rong, H. Analysis of loading stress of pavement structure using one-step forming cement-stabilized macadam base. E3S Web Conf. 2019(136), 04042. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/201913604042 (2019).

Xu, Q. Analysis of the rationality of cement-stabilized macadam base course construction plan. Jiangxi Building Materials 2017:195–197.

Liao, X. et al. Research on cracking of cement-stabilized macadam base during highway construction. J. Guangxi Univ. (Nat. Sci. Edition) 37, 716–722. https://doi.org/10.13624/j.cnki.issn.1001-7445.2012.04.011 (2012).

Ma, L., Wang, X. Investigation on construction design and technology of cement stabilized macadam base course for highway project. Art Design. pp 191–193 (2023).

Wang, Y. Research on construction technology of cement stabilized macadam base course in highway engineering construction. TranspoWorld https://doi.org/10.16248/j.cnki.11-3723/u.2023.20.021 (2023).

Zhu, H. High-grade highway semi-rigid base layer large thickness paving construction technology. Green Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.16767/j.cnki.10-1213/tu.2020.02.114 (2020).

JTG/T F20-2015; Technical Guidelines for Construction of Highway Roadbases (English Version). Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China (2015).

Ding, L., Wang, X., Zhang, M., Meng, J. & Hu, T. Construction quality control study of double-layer continuous paving for large-thickness cement-stabilized base. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020(1), 8845642. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8845642 (2020).

Jun, Y. Analysis of factors affecting the interface state between layers of large-thickness cement-stabilized macadam base layer paving continuously. Transp. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.3963/j.issn.1671-7570.2015.06.028 (2015).

Wang, J. The research of thick cement stabilized stone base layer continuous construction technology. Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University (2015).

Fang, N. et al. Plastic deformation analysis of double-layer continuous paving for large thickness water stabilized base course. J. Chongqing Univ. 42, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.11835/j.issn.1000-582x.2019.07008 (2019).

Ping, Q. Construction Technique and Quality Control of Double layers Continuous Paving of Cement Stabilized Macadam Base. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Technology 2013.

Yang, W. Construction process and quality control of double-layer continuous paving of cement stabilized macadam base. Transp. World https://doi.org/10.16248/j.cnki.11-3723/u.2020.07.009 (2020).

Qiao, Z. et al. Study on construction organization process of continuous double-layer paving semi-rigid base. China J. Highw. Transp. 29, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.19721/j.cnki.1001-7372.2016.03.006 (2016).

Huang, J. et al. Highway cement-stabilized macadam base double-layer continuous paving construction technology application research. Western China Commun. Sci. Technol. 10, 18–21. https://doi.org/10.13282/j.cnki.wccst.2023.10.007 (2023).

Zhang, H., Chen, X., Wang, Y. & Xiong, H. Comparative study on the mechanical properties of base mixture using continuous and discontinuous paving technologies. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 23(11), 3850–3866 (2022).

Li, Z. Research on construction of semi-rigid base on seasonal temperature. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Technology (2015).

Qing, H. analysis on the economic benefit of the maintenance costs of cement stabilized macadam base layered continuous paving. Value Eng. 35, 161–162. https://doi.org/10.14018/j.cnki.cn13-1085/n.2016.24.062 (2016).

Ma, S. et al. Research on rational construction program of cement stabilized macadam base. Highw. Eng. 39, 180–184 (2014).

JTG D50-2017. Specifications for Design of Highway Asphalt Pavement (English Version). Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China (2017).

JTG E51-2009. Test Methods of Materials Stabilized with Inorganic Binders for Highway Engineering (English Version). Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China (2009).

Transportation Research Board. Technical Guidelines for Construction of Highway Roadbases (JTG/T F20-2015). People’s Communications Press (2015).

Research Institute of Highway Ministry of Transport. Test Methods of Materials Stabilized with Inorganic Binders for Highway Engineering. China Communications Press, 2019, JTG E51-2009.

Hou, Z. Influence factors of mechanical response of cold recycled base pavement structure. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 30(44–47), 170 (2011).

Ma, S. et al. Research on shrinkage performance of dense skeleton based onlime fly-ash stabilized aggregate. J. Chongqing Jiaotong Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 32, 215–219 (2013).

Ma, S. et al. Highway performance of steel slag stabilized with inorganic binding materials. J. Hebei Univ. Technol. 35, 105–109 (2006).

Li, F. & Sun, L. J. Analysis of the Influence of base course modulus on the mechanics performance of asphalt pavement. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 41–43, 49 (2006).

Che, F. et al. Research on mixture component design of “skeleton-closed” lime-fly ash stabilized aggregate. J. Hebei Univ. Technol. 39, 96–99. https://doi.org/10.14081/j.cnki.hgdxb.2010.02.008 (2010).

Sun, L. & Luo, F. Nonstationary dynamic pavement loads generated by vehicles traveling at varying speed. J. Transp. Eng. 133(4), 252–263. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-947X(2007)133:4(252) (2007).

Wang, X., Fang, N., Ye, H. & Zhao, J. Fatigue damage analysis of cement-stabilized base under construction loading. Appl. Sci. 8(11), 2263. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8112263 (2018).

Funding

This research was funded by Jinhua Public Welfare Technology Application Research Project 2022 (No. 2022-4-309).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Shibin Ma; data curation, Ze Li.; formal analysis, Luyu Wang; funding acquisition, Junqin Liu; investigation, Junqin Liu; methodology, Ze Li.; project administration, Junqin Liu; resources, Junqin Liu; software, Luyu Wang.; supervision, Shibin Ma.; validation, Luyu Wang; writing—original draft, Luyu Wang; writing—review & editing, Shibin Ma. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Ma, S., Li, Z. et al. Study on the rationality of the construction scheme for cement-stabilized macadam base course. Sci Rep 16, 843 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30424-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30424-4