Abstract

Limited reports have highlighted the protective role of Healthy Nordic Food Index (HNFI) score against several chronic diseases like cancers and cardiovascular disorders. However, its beneficial role in obesity-related cardiometabolic risk factors is not well understood. In the current work, we examined the adherence to Nordic diet by estimating HNFI score and its association with metabolic syndrome and its components among Iranian population. In the current cross-sectional study, 339 individuals with obesity aged 20–50 years were recruited. Dietary intake was assessed by a validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Enzymatic methods were used to assess serum lipids and glycemic markers. Blood pressure was measured by sphygmomanometer and body composition with bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA). No significant differences were found in age, sex distribution, waist circumference, body mass index categories, socioeconomic status score, fat mass percentage, fat-free mass, basal metabolic rate across quartiles or physical activity of HNFI (all P > 0.05). Also, higher energy, saturated fatty acids, sugar, fiber, β-carotene, yogurt, milk, and potatoes was shown in higher HNFI categories (P < 0.05). Higher adherence to Nordic diet was accompanied with lower systolic blood pressure (SBP, P < 0.001), total cholesterol (P,0.047) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations (P, 0.034) after adjusting for age, body mass index (BMI), physical activity level). In multinomial logistic regression analysis, HNFI showed no significant association with most obesity-related cardiometabolic risk factors. After adjustment for age and sex, participants in the third HNFI quartile had lower SBP, DBP, TC compared to participants in first HNFI quartile (P < 0.05). No significant associations were observed for FBS, TG, insulin, HOMA-IR, α-MSH, and AgRP (OR > 0.05). According to our results, higher adherence to Nordic diet was associated with favorable cardio-metabolic risk factors among apparently healthy adults with obesity. Further researches are warranted to better clarify these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is recognized as a chronic, progressive, and relapsing but manageable condition that is a complex, multifactorial neurobehavioral disease in which excessive accumulation of body fat leads to adipose tissue dysfunction and altered fat-related mechanical forces. These changes contribute to a wide range of adverse outcomes, including metabolic disturbances, biomechanical impairments, and negative psychosocial effects1. Obesity is a major risk factor for cardiometabolic diseases because it involves a complex interplay of hormonal, inflammatory, and hemodynamic mechanisms. As excess adiposity develops, it not only impairs adipocyte function but also promotes systemic insulin resistance, and it further activates the sympathetic nervous system as well as the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS). These changes act synergistically to increase sodium retention and induce vasoconstriction, and together they contribute to the development of hypertension2. In parallel, obesity-related dyslipidemia is characterized by elevated triglycerides, increased small dense LDL particles, and reduced HDL cholesterol, largely driven by increased hepatic VLDL production and impaired lipoprotein metabolism, thereby amplifying atherogenic risk3. Moreover, chronic low-grade inflammation and an excess of free fatty acids act in concert to disrupt insulin signaling in key metabolic tissues, and this combination predisposes individuals to insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, and ultimately the development of type 2 diabetes4,5. These metabolic abnormalities synergize with hypertension and dyslipidemia to accelerate the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, and this process is further compounded by structural cardiac changes, endothelial dysfunction, and systemic inflammation. Consequently, obesity functions as a central driver of metabolic dysregulation, and it substantially elevates the risk of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular morbidity6.

In addition to these peripheral mechanisms, obesity is strongly associated with disruptions in central appetite-regulating pathways, and this is particularly evident in alterations of melanocortin signaling. Within this system, hormones such as melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) serve as critical regulators of energy balance and appetite, as they modulate both satiety and food intake; however, when these pathways are dysregulated, they contribute directly to the onset and progression of obesity7.

One of the evaluation indices for diet quality is the Healthy Nordic Food Index (HNFI), which consists of 6 items from the traditional Nordic diet that is responsible for the health effects of the Nordic diet8; these six food items are fish, cabbages, barley, whole-grain bread, apples and pears, and root vegetables9. Other plant-based dietary patterns, including the Mediterranean and DASH, have some similarities with the Nordic Diet10. In the Nordic region, the Mediterranean dietary pattern is a healthier and more useful alternative to the existing diet and has more beneficial effects on public health8. The major specifications of the Mediterranean diet contain a variety of vegetables and fruits, whole-grain cereals, nuts, and legumes, olive oil, white meats such as fish and poultry; Recommended to consume less red meat; and moderate consumption of wine11. The diversity of agricultural and livestock products in the Nordic region is limited, but in terms of plant products like berries, cabbages, apples, pears, root vegetables, oats, and rye is rich; besides, the coastlines in these countries provide a high abundance of fish12. Vitamins C, K, folate, iron, dietary fiber, and other bioactive components are abundant in the HNFI components, which can help to prevent chronic diseases13. Furthermore, a new WHO report assessed the health benefits of a healthy Nordic diet and encouraged Nordic countries to investigate how it can be transformed into population-based dietary recommendations14.

Many studies indicate that a healthy Nordic diet has significant positive effects on markers of type 2 diabetes risk, including body weight and insulin sensitivity, also it caused a significant reduction of plasma levels of cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1) and apolipoprotein B (apo B) as a result reduction in cardiovascular risk15,16. Additionally, compared to the control diet, the healthy Nordic diet reduced ambulatory diastolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure after 12 weeks17.

Most of the studies have shown that the mean fish consumption among Iranian adults was 11.3 g/d18; also, the average per capita consumption of vegetables in Iran is 286 g per day19, cabbage is commonly grown in the Urmia, west and east Azerbaijan and numerous other provinces in Iran20. Consumption of cereals and bread among Iranian population is 40% higher compared with other parts of the world and is the main food item (food staple) among Iranian population19. This is evidently clear that in Iran, people follow diets similar to those found in Nordic nations.

As a consequence of the availability of HNFI items in Iran and due to the Nordic diet’s beneficial effects on some cardio-metabolic factors including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as type 2 diabetes risk factors such abdominal obesity and obesity-related inflammatory markers21,22,23, Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between adherence to the Nordic diet and obesity-related cardiometabolic risk factors such as blood pressure, fasting glucose, lipid profile, insulin resistance, and appetite-regulating hormones such as α-MSH, AgRP in obese individuals. To our knowledge, this is among the first studies to comprehensively assess both conventional and novel markers of cardiometabolic health in relation to the Nordic dietary pattern.

Methods and materials

Patients and public involvement

This study is a cross-sectional study. participants included 339 participants with obesity from Tabriz. The participants were gathered from recent projects among patients with obesity in the mentioned university24,25. We invited all participants by public announcements and the age range of all 339 participants was between 20 and 50 years old and their body mass index was more than 30 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, lactation, menopause, recent bariatric surgery, cardiovascular disease, cancer, hepatic or renal diseases, diabetes mellitus, or consumption of drugs effective in reducing or increasing weight. Written consent was obtained from all participants and the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran approved the proposal of this study (code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.687).

General characteristics and anthropometric assessments

Participants answered a socio-demographic self-administered questionnaire including age, sex, smoking status, education attainment, marital status, occupation, medical histories, and family size; afterward, socioeconomic status (SES) score was calculated for each participant. Then by the bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) method, the body composition of participants was determined (Tanita, BC-418 MA, Tokyo, Japan). Other anthropometric data including height and weight were obtained using a wall-mounted stadiometer and a Seca scale (Seca co., Hamburg, Germany). Modified short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to estimate the physical activity of participants26. Waist circumference (WC) was determined using a tape measure to the nearest 0.1 cm at the midpoint between the lower costal margin and the iliac crest, However, hip circumference (HC) was measured the part that yields the maximum diameter over the buttocks and was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. In the next step, BMI and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were calculated via available data. Blood Pressure monitoring was done with a standard mercury sphygmomanometer and then the mean of the two measurements was reported. Anthropometric parameters and other measurements taken by trained personnel.

Dietary assessments

The participants answered a validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), modified for the Iranian population27. Participants have reported the frequency and amount of food items consumed every day, month, and yearly basis. Then, the Frequency of consumption of each item in the questionnaire is converted to grams. The collected data were used to construct Nordic diet scores. In our study, 6 nutrients were included in this index: fish, cabbages, barley, whole-grain bread, apples and pears, and root vegetables28. Due to the low consumption of barley in the Iranian population, we used frumenty instead of oats. Wholegrain bread including Iranian bread of “Sangak” and “Barbari”29. For HNFI diet score calculation, the consumption of each participant is compared with the median of each item, then one point per component was given to each individual who consumed more than this median value, and 0 point vice versa. The total HNFI score was calculated by adding these scores. The total healthy Nordic food index could take values from 0 (low adherence) to 6 (high adherence)8.

Biochemical assessment

10 ml of venous blood samples were taken from each individual and the blood sample was centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min to separate serum and plasma samples. Serum total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and fasting blood sugar (FBS) were analyzed using a kit (Pars Azmoon, Tehran, Iran). additionally, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level was determined with the Friedewald Eq.(30). We used Enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay kits to measure concentrations of serum insulin and Plasma α-MSH and AgRP levels. (Bioassay Technology Laboratory, Shanghai Korean Biotech, Shanghai City, China). The lowest detectable range for AgRP was 1.03 pg/ml and for α-MSH levels 5.07 ng/L respectively. Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated with the following formula: fasting insulin (µ IU/ml) × fasting glucose (mmol/l) /22.5 and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index QUICKI as 1/ [log fasting insulin (µU/mL) + log glucose (mmol/L)].

Statistical analyses

Statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 21.0 with a significance level of < 0.05. Data are described as frequency (%) for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. The differences in discrete and continuous variables across different adherence to Nordic diet score categories were compared using the Chi-square test and one-way ANOVA respectively. ANCOVA was used for the comparison of biochemical variables after adjustment for confounders (BMI, age and physical activity). The association between HNFI diet score with quartiles of adherence to HNFI. For analysis, because of the ordinal nature of our grouping variable (e.g. HNFI quartiles) we used the Jonckheere-Terpstra test as a rank-based test that is used to determine statistically significant trend difference between an ordinal independent variable and a continuous or ordinal dependent variable31.

Results

A total of 339 participants were divided into quartiles based on Nordic diet adherence categories: first quartile (0–2 points, N = 96), second quartile (3 point, N = 72), third quartile (4 point, N = 90) and fourth quartile (5–6 points, N = 81). The general characteristics of the study population stratified by adherence to Nordic diet are presented in Table 1. Distribution of Healthy Nordic Food Index scores in study population presented in Fig. 1. The population of individuals who scored 4 was the maximum (26.54%), while the lowest population was in the score zero category (2.35%). There were no significant differences in characteristics of participants across four groups. Adherence to Nordic diet showed no significant relationship with anthropometric data such as BMI, WC, FFM, FM. The comparison of energy and macronutrient intakes of the study population by HNFI showed that energy, saturated fatty acids, sugar, fiber, β-carotene, yogurt, milk, potatoes, processed meat intake increased among participants who achieved higher HNFI, whereas intake levels of carbohydrate, protein, fat and other dietary intakes did not differ between four adherence categories (Table 2).

The median intake of HNFI components as follows: whole grain bread (111.10 gr/day), fish (6.37 gr/day), cabbages (3.10 gr/day), oatmeal (3.53 gr/day), apples, and pears (83.71 gr/day) and root vegetables (47.04 gr/day); Table 3 shows the increasing intake of all of six components of this intake in higher adherence categories.

Among apparently healthy participants with obesity, higher HNFI was associated with lower SBP, TC, and LDL-C levels after adjusting for confounders, including energy intake, age, BMI, and physical activity (P,<0.001, 0.047 and 0.034 respectively). While the overall ANCOVA indicated a significant association of HNFI quartiles with SBP, TC, and LDL-C levels, pairwise comparisons between quartiles, adjusted for confounders, did not reach statistical significance after Bonferroni correction (P > 0.05). No significant differences were observed in serum insulin, HOMA-IR, QUICKI, α-MSH, and AgRP across quartiles of HNFI adherence (Table 4).

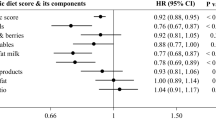

Multinomial logistic regression was implemented to assess the association between obesity-related cardiometabolic risk factors and HNFI across quartiles, with the lowest quartile (Q1) considered as the reference. As shown in Table 5, no statistically significant were observed between SBP and HNFI in crude model and model that adjusted for age, BMI, sex, physical activity, SES, and energy intake. However, in the model adjusted just for age and sex HNFI in the third quartile was inversely associated with SBP, DBP, TC and LDL (P < 0.05). FBS, TG and TC revealed non-significant associations with HNFI across quartiles (P > 0.05). In the multivariable-adjusted model, LDL-C exhibited an inverse association in the third quartile (OR, 0.983, 95% CI: 0.969–0.997, P = 0.020). For HDL-C, an inverse association was noted in the age-sex–adjusted model, which became nonsignificant after further adjustment (OR, 0.994, 95% CI: 0.994–1.046, P = 0.805). No significant associations were found between HNFI and insulin, HOMA-IR, α-MSH, or AgRP levels in any model.

Discussion

In this current cross-sectional study, the adherence of the Iranian population to the Nordic diet was assessed by the FFQ questionnaire then the relationship of adherence to the Nordic diet and obesity-related cardiometabolic risk factors have been investigated. For both men and women, the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health cohort research discovered an inverse relationship between a healthy Nordic index and the risk of type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM)32. In similar large Danish cohort research of men and women, adherence to a healthy Nordic diet was related with a decreased incidence of stroke, the findings of that study show that a healthy Nordic diet based on traditional Nordic items could be proposed as a regional alternative to the Mediterranean diet for stroke prevention33. In a population-based study conducted among Iranian adults with type 2 diabetes, adherence to the Nordic diet was found to be significantly associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, LDL levels, and blood pressure. Individuals with lower adherence exhibited higher levels of LDL-cholesterol, elevated systolic blood pressure, and a greater prevalence of obesity34. Many investigations have shown consumption of a diet rich in whole grain and fish was associated with an increase of HDL-c and reduction of postprandial insulin and triglycerides responses35,36,37. Moreover, high amounts of fiber in a diet appears to enhance insulin secretion, serum insulin level, improved β-cell function, and reduced insulin resistance and blood glucose level38,39. Insulin resistance plays a key role in the development of metabolic disorders such as T2DM and cardiovascular diseases, with higher HOMA-IR levels consistently linked to an increased risk of T2DM in both healthy and metabolically compromised individuals40. Furthermore, adherence to the Nordic dietary pattern has been linked to favorable metabolic outcomes. In one study, participants following the healthy Nordic diet showed significant reductions in fasting insulin concentrations and HOMA-IR15. Similarly, a meta-analysis of two studies found that stronger adherence to this dietary pattern was linked to better insulin sensitivity, as shown by lower HOMA-IR values41. In contrast, our results did not show a significant connection between following the Nordic diet and HOMA-IR levels. This suggests that the diet’s effect on insulin resistance may differ among populations or be influenced by specific dietary habits or lifestyle factors.

Studies demonstrated that the health benefits of cruciferous vegetables such as cabbages are associated with the anti-inflammatory effects of these vegetables42. The positive effect of cruciferous vegetables in preventing cardiovascular diseases has been recently discussed43. Sulforaphane and iso-thiocyanate in this family of vegetables are responsible for the health effects of these vegetables that reduce oxidative stress and inflammation in the circulatory system via the activation of transcription factors44. Oatmeal as another component of HNFI, significantly increased the short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) concentration in the intestine by fermentation, then lessens obesity and related metabolic disorders while modifying intestinal microbial composition45. Some of suggested possible mechanistic pathways of the positive effects of HNFI score on human health is presented in Fig. 2. Root vegetables such as special carrots are a rich source of beta-carotene, it is proven that β-Carotene has antioxidant capacity so it has preventive effects on diseases such as obesity and T2DM46.

Summarized beneficial effects of Healthy Nordic Food Index score (NF-kb, nuclear factor kappa-B; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; VLDL-C, very low density lipoprotein cholesterol; T2DM, type two diabetes mellitus; α-MSH, alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone; AgRP, agouti-related peptide; PYY, peptide YY; GLP-1, glucagon like peptide-1; SCFA, short chain fatty acid; AMPK, adenosine mono-phosphate-activated protein kinase).

Interestingly, our study our study found that higher adherence to the Nordic diet was associated with increased intakes of sugar, saturated fatty acids, and processed meat. Several considerations may explain this finding. Firstly, many Nordic diet adherence scores prioritize the consumption of positive dietary components but do not sufficiently penalize higher intakes of nutritionally unfavorable foods. Secondly, cultural and regional adaptations of the Nordic diet frequently incorporate traditional foods rich in saturated fat and processed meats, including sausages, cured meats, and cream-based dishes, which may elevate SFA and processed meat intake despite an otherwise healthy dietary pattern47. Thirdly, higher overall energy intake among participants in higher quartiles of HNFI may partly drive the absolute increases in sugar and saturated fat consumption, as total caloric intake can influence nutrient intake levels. Notably, when adjusting for confounders such as energy intake, body mass index, and physical activity, the initially observed associations between adherence to the Nordic diet and intake of sugar and SFAs lost significance. This complexity highlights the challenge of dietary pattern assessment and supports calls for refining Nordic diet indices to incorporate both beneficial and detrimental components to more accurately capture overall diet quality.

The present study evaluated the association of Nordic dietary pattern scores and obesity-related cardiometabolic risk factors to investigate whether does adhere to the Nordic diet has beneficial health effects on this this risk factors or not? In our study, we observed a significant reduction in TC, LDL-C and SBP in highest versus lowest quartiles of HNFI score. Moreover, a non-significant reduction was also observed for DBP, TG values and a non-significant increase in insulin and α- MSH values in highest versus lowest quartiles of HNFI score. In multinomial logistic regression analyses, no statistically associations were found between HNFI quartiles and most cardiometabolic risk factors in crude or adjusted analyses. However, in the age- and sex-adjusted model, the third quartile of HNFI showed inverse associations with SBP, DBP, TC, and LDL, although the observed significant associations disappeared after adjusting.

In conclusion, a diet consisting of fiber, fish, fresh vegetables, and fruits like HNFI score was associated with better cardio-metabolic risk factors48,49.

Key strengths of the present study include the first assessment of central appetite-regulating hormones, such as AgRP and α-MSH, alongside traditional metabolic markers. This integrated approach provides a more holistic understanding of the mechanisms underlying obesity. Moreover, the HNFI was carefully adapted to align with the dietary habits of the Iranian population, ensuring greater cultural and contextual relevance. Dietary intake was also evaluated using a validated and reliable FFQ tailored to the target population. In addition, multiple adjustment models were employed to account for potential confounders, thereby enhancing the rigor and credibility of the findings. Possible limitations of the current study should also be addressed; The design of the present study is cross-sectional, which itself causes limitations such as causal inference is difficult to make; the situation could have turned out differently if a different time frame had been picked, Variables are examined in cross-sectional studies at a specific point in time. Cross-sectional research cannot demonstrate causality without the ability to show temporal precedent. Additionally, the FFQ was not originally developed to assess compliance with a healthy Nordic diet, although it includes most of its food items that increase its validity and generalizability. Therefore, the unavailability of some of the Nordic diet components in the usual diet of the Iranian population, recall bias due to subjective nature of questionnaire-based data and the impossibility of causal inference due to cross-sectional design of the current study make us to interpret the obtained results with caution. Further longitudinal or interventional studies are warranted find more reliable and generalizable results.

Clinicians may consider recommending the Nordic dietary pattern as a complementary lifestyle strategy for patients with elevated cardiometabolic risk—especially those presenting with dyslipidemia, hypertension, or early signs of metabolic syndrome. From a clinical standpoint, these results highlight the potential value of incorporating Nordic diet principles into standard dietary counseling and cardiac rehabilitation practices. Moreover, they underscore the need for additional randomized controlled trials to further confirm its effectiveness as an evidence-based nutritional approach for reducing cardiometabolic risk.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to some restrictions that applied by the ethical committee but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bays, H. et al. Adult Obesity Algorithm eBook: Detailed overview of Obesity Medicine. (2021).

Kanbay, M. et al. From pathophysiology to novel approaches for obesity-associated hypertension. Clin. Kidney J. :sfaf218. (2025).

DeFronzo, R. A. & Ferrannini, E. Insulin resistance: a multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 14 (3), 173–194 (1991).

Jin, X. et al. Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases. Acta Pharm. Sinica B. 13 (6), 2403–2424 (2023).

Bays, H. E. et al. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease: A joint expert review from the obesity medicine association and the National lipid association 2024. J. Clin. Lipidol. 18 (3), e320–e50 (2024).

Ruze, R. et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1161521 (2023).

Wu, Q., Chen, J., Hua, T. & Cai, J. Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone-mediated appetite regulation in the central nervous system. Neuroendocrinology 113 (9), 885–904 (2023).

Olsen, A. et al. Healthy aspects of the nordic diet are related to lower total mortality. J. Nutr. 141 (4), 639–644 (2011).

Gunge, V. et al. Adherence to a healthy nordic food index and risk of myocardial infarction in middle-aged danes: the diet, cancer and health cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 71 (5), 652–658 (2017).

Jalilpiran, Y., Jayedi, A., Djafarian, K. & Shab-Bidar, S. The nordic diet and the risk of non-communicable chronic disease and mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62 (11), 3124–3136 (2022).

Esposito, K., Ceriello, A. & Giugliano, D. Diet and the metabolic syndrome. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 5 (4), 291–296 (2007).

Bere, E. & Brug, J. Towards health-promoting and environmentally friendly regional diets–a nordic example. Public Health. Nutr. 12 (1), 91–96 (2009).

Hajjar, M. et al. Association of the healthy nordic food index with risk of bladder cancer: a case–control study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 76 (3), 482–486 (2022).

Jensen, T. M. E. et al. Adherence to the healthy nordic food index in the Norwegian women and cancer (NOWAC) cohort. Food Nutr. Res. ;62. (2018).

Adamsson, V. et al. Effects of a healthy nordic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in hypercholesterolaemic subjects: a randomized controlled trial (NORDIET). J. Intern. Med. 269 (2), 150–159 (2011).

Poulsen, S. K. et al. Health effect of the new nordic diet in adults with increased waist circumference: a 6-mo randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99 (1), 35–45 (2014).

Brader, L., Uusitupa, M., Dragsted, L. O. & Hermansen, K. Effects of an isocaloric healthy nordic diet on ambulatory blood pressure in metabolic syndrome: a randomized SYSDIET sub-study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 68 (1), 57–63 (2014).

Mirmiran, P., Asghari, G., Dizavi, A., Farhadnejad, H. & Azizi, F. The Association between Fish Consumption and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome in Adults: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research, 2019).

Abdi, F., ATARODI, K. Z., Mirmiran, P. & Esteki, T. Surveying global and Iranian food consumption patterns: A review of the literature. (2015).

Yousefdoost, V. & Ghosta, Y. First report of sclerotinia head rot of cabbage in Iran. Iran. J. Plant. Pathol. ;49(3). (2013).

Kanerva, N., Kaartinen, N. E., Schwab, U., Lahti-Koski, M. & Männistö, S. Adherence to the Baltic sea diet consumed in the nordic countries is associated with lower abdominal obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 109 (3), 520–528 (2013).

Kanerva, N. et al. Associations of the Baltic sea diet with obesity-related markers of inflammation. Ann. Med. 46 (2), 90–96 (2014).

Ramezani-Jolfaie, N., Mohammadi, M. & Salehi-Abargouei, A. The effect of healthy nordic diet on cardio-metabolic markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 58 (6), 2159–2174 (2019).

Khodarahmi, M., Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. & Abbasalizad Farhangi, M. A structural equation modeling approach for the association of a healthy eating index with metabolic syndrome and cardio-metabolic risk factors among obese individuals. PloS One. 14 (7), e0219193 (2019).

Farhangi, M. A., Vajdi, M., Nikniaz, L. & Nikniaz, Z. Interaction between vascular endothelial growth factor-A (rs2010963) gene polymorphisms and dietary diversity score on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with metabolic syndrome. Lifestyle Genomics. 13 (1), 1–10 (2020).

Vasheghani-Farahani, A. et al. The Persian, last 7-day, long form of the international physical activity questionnaire: translation and validation study. Asian J. Sports Med. 2 (2), 106–116 (2011).

Mirmiran, P., Esfahani, F. H., Mehrabi, Y., Hedayati, M. & Azizi, F. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public. Health Nutr. 13 (5), 654–662 (2010).

Hajjar, M. et al. Association of the healthy nordic food index with risk of bladder cancer: a case–control study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. :1–5. (2021).

Sadeghi, O., Hassanzadeh-Keshteli, A., Afshar, H., Esmaillzadeh, A. & Adibi, P. The association of whole and refined grains consumption with psychological disorders among Iranian adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 58 (1), 211–225 (2019).

Friedewald, W. T., Levy, R. I. & Fredrickson, D. S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 18 (6), 499–502 (1972).

Vock, M. & Balakrishnan, N. A Jonckheere–Terpstra-type test for perfect ranking in balanced ranked set sampling. J. Stat. Plann. Inference. 141 (2), 624–630 (2011).

Lacoppidan, S. A. et al. Adherence to a healthy nordic food index is associated with a lower risk of type-2 diabetes—The Danish diet, cancer and health cohort study. Nutrients 7 (10), 8633–8644 (2015).

Hansen, C. P. et al. Adherence to a healthy nordic diet and risk of stroke: a Danish cohort study. Stroke 48 (2), 259–264 (2017).

Daneshzad, E. et al. Association of modified nordic diet with cardiovascular risk factors among type 2 diabetes patients: a cross-sectional study. J. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Res. 10 (3), 153 (2018).

Lankinen, M. et al. Effects of whole grain, fish and bilberries on serum metabolic profile and lipid transfer protein activities: a randomized trial (Sysdimet). PLoS One. 9 (2), e90352 (2014).

Manninen, S. M. et al. Intake of fatty fish alters the size and the concentration of lipid components of HDL particles and camelina sativa oil decreases IDL particle concentration in subjects with impaired glucose metabolism. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 62 (10), 1701042 (2018).

Giacco, R. et al. A whole-grain cereal-based diet lowers postprandial plasma insulin and triglyceride levels in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metabolism Cardiovasc. Dis. 24 (8), 837–844 (2014).

Juntunen, K. S., Laaksonen, D. E., Poutanen, K. S., Niskanen, L. K. & Mykkänen, H. M. High-fiber Rye bread and insulin secretion and sensitivity in healthy postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77 (2), 385–391 (2003).

Erukainure, O. L. et al. Fiber-enriched biscuit enhances insulin secretion, modulates β-cell function, improves insulin sensitivity, and attenuates hyperlipidemia in diabetic rats. PharmaNutrition 1 (2), 58–64 (2013).

González-González, J. G. et al. HOMA-IR as a predictor of health outcomes in patients with metabolic risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. High. Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 29 (6), 547–564 (2022).

Zimorovat, A., Mohammadi, M., Ramezani-Jolfaie, N. & Salehi-Abargouei, A. The healthy nordic diet for blood glucose control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Acta Diabetol. 57 (1), 1–12 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Cruciferous vegetable intake is inversely correlated with Circulating levels of Proinflammatory markers in women. J. Acad. Nutr. Dietetics. 114 (5), 700–708 (2014). e2.

Zhang, X. et al. Cruciferous vegetable consumption is associated with a reduced risk of total and cardiovascular disease mortality. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 94 (1), 240–246 (2011).

Mori, N. et al. Cruciferous vegetable intake and mortality in middle-aged adults: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 38 (2), 631–643 (2019).

Tian, L. et al. Effect of oat and soybean rich in distinct non-starch polysaccharides on fermentation, appetite regulation and fat accumulation in rat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 140, 515–521 (2019).

Marcelino, G. et al. β-Carotene: preventive role for type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity: A review. Molecules 25 (24), 5803 (2020).

Blomhoff, R. et al. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023: Integrating Environmental Aspects (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2023).

Kastorini, C-M. & Panagiotakos, D. B. Dietary patterns and prevention of type 2 diabetes: from research to clinical practice; a systematic review. Curr. Diabetes. Rev. 5 (4), 221–227 (2009).

Ahluwalia, N., Andreeva, V. A., Kesse-Guyot, E. & Hercberg, S. Dietary patterns, inflammation and the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab. 39 (2), 99–110 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the study participants. We also are thankful from Research Undersecretary of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for their financial support (Grant number:70124).

Funding

Present study has been financially supported by a grant from Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. (Registration code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.687). The funders had no role in hypothesis generation, recruiting and designing the study. Their role was only financial supporting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAF and NN were involved in manuscript writing, MAF also supervised the project, analyzed data, and revised the paper. All of authors read the article and agreed with its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study protocol has been approved by the ethics committee of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (registration code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.687). Written informed consent was obtained from all of the participants before participation in the study. All methods in the current research were performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki’s guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nikrad, N., Abbasalizad Farhangi, M. Adherence to the healthy nordic food index is associated with favorable obesity-related cardiometabolic risk factors among apparently healthy obese individuals. Sci Rep 16, 928 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30482-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30482-8