Abstract

Postoperative pneumonia (POP) is a prevalent and serious complication following thoracic surgery, substantially increasing morbidity, mortality, and healthcare expenditures. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of perioperative oral care (POC) in reducing the incidence of POP. A comprehensive literature search was conducted across the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, PubMed, and Embase from their inception through September 26, 2024. We included all observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed the impact of POC on POP reduction. A total of 25 studies, involving 52,227 patients (24,964 in the POC group and 27,263 in the control group), were included in the final analysis, comprising 9 RCTs and 16 observational studies. The incidence of POP was 2,887 cases (11.6%) in the POC group, compared with 3,438 cases (12.6%) in the control group. The meta-analysis revealed that POC was associated with a significantly reduced incidence of POP in patients undergoing thoracic surgery (RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44–0.67; p < 0.001; I² = 72%). In conclusion, POC significantly reduces the incidence of POP in thoracic surgery patients, and its integration into perioperative protocols may improve clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative pneumonia (POP), a nosocomial pulmonary infection occurring after surgery, classified as hospital-acquired pneumonia, is one of the most prevalent complications following thoracic surgery1. It is associated with increased mortality, a substantial reduction in quality of life, prolonged hospital stays, and elevated healthcare costs2,3. In cardiothoracic surgery, procedures involving the lung parenchyma, esophagus, heart, or mediastinum can directly or indirectly affect the anatomical structure and functional integrity of the respiratory system, leading to pulmonary ventilation disorders, decreased airway clearance ability, and increased risk of pathogenic microorganism migration, which increases the risk of POP4,5. Studies have indicated that the incidence of POP following thoracic surgery ranges from 6.2% to 18.3%6,7,8,9,10. Consequently, implementing effective early interventions is critical to prevent POP following thoracic surgery.

Aspiration of oral and oropharyngeal secretions represents a frequent mechanism for POP development11. The accumulation of dental plaque fosters poor oral hygiene, thereby increasing the risk of postoperative pneumonia2. Perioperative oral care (POC), which employs an approach of mechanical cleansing (e.g., brushing, scraping) or chemical disinfection (e.g., mouthwash, spray), mitigates bacterial colonization by removing plaque and restoring saliva’s protective functions, thereby effectively reducing pneumonia risk12,13,14,15,16,17. Meta-analyses showed that oral care was effective in reducing the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care unit patients, as well as POP in cardiac surgery patients18,19,20.

Although evidence supports POC as a cost-effective method for reducing postoperative pneumonia18,19,21, its implementation has yet to become routine in thoracic surgical practice22. This oversight may result from inadequate awareness among nursing staff regarding the critical role of oral care in surgical patient outcomes, contributing to insufficient patient education, poor adherence, and reduced efficacy of interventions23. Evaluating the efficacy of perioperative oral care in thoracic surgery can aid in refining and updating their consensus guidelines on perioperative management to optimize postoperative recovery. To address this issue, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the association between perioperative oral care interventions and the incidence of postoperative pneumonia in thoracic surgery patients, with the objective of assessing the effectiveness of POC in reducing pneumonia occurrence.

Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The study protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42024599031).

Search strategy

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science for relevant studies published from their inception until September 26, 2024. The search strategy combined terms for thoracic procedures (e.g., esophagus, lung, rib fractures, mediastinum, thoracic surgery, cardiac) with terms for oral care (e.g., oral hygiene, mouth care, oral care) and pneumonia. PubMed’s MeSH terms were adapted to the corresponding Emtree vocabulary in Embase. Each conceptual group was supplemented with relevant free-text terms, using truncation and Boolean operators as needed. The search was restricted to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and analytical observational studies (cohort, cross-sectional, or case-control designs). The complete search strategies for all databases are available in the Supplementary Material.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included based on the following criteria: (1) design: randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or case-control studies; (2) population: patients undergoing thoracic surgery; (3) intervention: POC compared to non-POC control; and (4) outcome: incidence of POP.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded for any of the following reasons: (1) publication type: duplicates, reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, letters, case reports, or animal studies; non-English publications; (2) population: studies not exclusively involving thoracic surgery patients; (3) intervention: studies without a POC intervention, both groups received POC, or comparing two active POC regimens without a true control; (4) outcome: studies not reporting POP incidence; (5) data: unavailable full text, insufficient patient data, or restricted data access. Two authors (Duan and Li) independently screened the studies, with disagreements resolved by consensus or adjudication by a third author (Li).

Data extraction

After removing duplicates using EndNote (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA), two authors (Duan and Li) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved citations against the preliminary inclusion criteria. The full texts of potentially eligible studies were then reviewed to confirm final eligibility. Two authors (Duan and Li) independently extracted data using a standardized form, with any discrepancies resolved by consensus or by a third author (Li). The data extracted from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included: (1) general characteristics, including author, publication year, and country; (2) participant details, such as the type of surgery performed, the number of patients in the intervention and control groups, and the diagnostic criteria for POP; (3) details of the POC intervention, including concentration, timing, and frequency; (4) control group characteristics, such as the type of placebo, frequency and timing of use; and (5) POP diagnostic criteria; primary outcome measure, specifically the incidence of POP. For observational studies, extracted data included: (1) general characteristics; (2) participant details; (3) exposure definition; (4) control group characteristics; and (5) POP diagnostic criteria; the incidence of POP.

Quality assessment

Two authors (Duan and Li) independently assessed the quality of each included study. The risk of bias for all included observational studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which assesses three domains: patient selection, comparability, and exposure/outcomes. Studies scoring ≥ 7 were classified as low risk, those scoring 4–6 as moderate risk, and those scoring < 4 as high risk. The quality of included RCTs was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, which assigns ratings of “low,” “unclear,” or “high” risk across six domains: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases24.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the incidence of POP. Dichotomous outcome measures were reported as odds ratios (ORs) or relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity among included studies was assessed using the I² test and Q statistic. Heterogeneity was categorized as follows: high (I² ≥ 75%), moderate (50% ≤ I² < 75%), or low (25% < I² < 50%)25. When heterogeneity was low (I² < 50%), a fixed-effects model was used. Otherwise, a random-effects model was applied to account for variability across studies. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore potential sources of heterogeneity related to the methods of POC. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the pooled results by sequentially excluding low-quality studies one at a time. All analyses were performed using RevMan 5.3 software (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

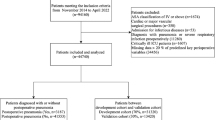

A total of 1,333 relevant studies were retrieved as of the search date for the meta-analysis: 60 from PubMed, 735 from Embase, 343 from Web of Science, 192 from the Cochrane Library, and 3 from other sources. After removing duplicates, 1,205 studies remained. Following title and abstract screening, 1145 studies were excluded. Subsequently, 60 full-text articles were assessed, of which 25 studies—comprising 16 observational studies and 9 RCTs—met the inclusion criteria. The search results are presented in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

As detailed in Table 1, the included studies investigated the potential association between POP and POC. In the RCTs, 1,641 of 3,834 participants (42.8%) received POC. In the observational studies, 23,323 of 48,393 eligible participants (48.2%) received POC. The incidence of POP was 2,887 cases (11.6%) in the POC group, compared with 3,438 cases (12.6%) in the control group, with a cumulative total incidence of approximately 12.1%. The oral care interventions included preoperative dental care by a dentist, addressing periodontitis and dental caries, as well as structured perioperative tooth brushing, with or without chlorhexidine. Of the RCTs, four implemented preoperative oral hygiene protocols, while the remaining five administered oral care interventions both preoperatively and postoperatively. Of the observational studies, nine implemented oral care exclusively before surgery, while seven maintained oral hygiene protocols throughout the entire perioperative period. The included studies employing chlorhexidine predominantly used concentrations of 0.12% and 0.2%, with application frequencies ranging from once to four times daily. The 25 included studies comprised 9 cardiac surgeries, 15 lung or esophageal cancer procedures, and 1 elective or urgent thoracic surgery. The diagnosis of POP was based on multiple criteria, including radiographic evidence from chest X-rays, consolidation on computed tomography, elevated body temperature, increased white blood cell count, elevated serum C-reactive protein levels, identification of pathogenic microorganisms, and sputum culture results. These criteria were applied consistently across both RCTs and observational studies included in this analysis.

Quality assessment and publication bias

Of the nine RCTs included in this analysis, seven studies clearly reported their randomization methods, and six studies adequately described the implementation of allocation concealment. Notably, only two studies demonstrated low risk of attrition bias, selective reporting bias, and other potential biases, while also adequately describing the use of blinding techniques. The methods for randomization and allocation concealment were poorly described in the remaining studies (Fig. 2). The NOS was used to assess the quality of the 16 included observational studies, as detailed in Table 2. Of these, five studies were rated as low quality, ten as moderate quality, and one as high quality based on the NOS criteria. The mean overall NOS score was 5.9, with average scores of 2.8, 1.4, and 1.7 for the selection, comparability, and exposure domains, respectively. Significant publication bias was observed upon evaluation of funnel plot asymmetry (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Primary outcome: postoperative pneumonia

The primary outcome of this study was the incidence of POP. Meta-analysis of all eligible studies demonstrated that perioperative oral care significantly reduced the incidence of POP (RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.44–0.67; p < 0.001). A heterogeneity test revealed moderate variability among study results (I² = 72%; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Subsequent sensitivity analysis showed that excluding the study by Ishimaru et al. reduced heterogeneity (I² decreased from 72% to 40%) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Subgroup analyse of different oral care methods

This subgroup analysis evaluated the efficacy of different oral care modalities in preventing POP. Five of the nine RCTs evaluated chlorhexidine mouthwash. The incidence of POP was lower in the chlorhexidine group (100, 8.1%) than in the control group (139, 11.2%). With moderate heterogeneity (I² = 58%, p = 0.05), chlorhexidine mouthwash significantly reduced the incidence of POP (RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54–0.88; p = 0.002). The remaining four studies evaluated chlorhexidine-containing mouthwash combined with mechanical cleaning. The incidence of POP was significantly lower in the POC group (n = 12, 3%) compared to the control group (n = 66, 6.9%), demonstrating a protective effect (RR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.17–0.58; p = 0.0003), with no statistical heterogeneity (I²= 0%, p = 0.98). The overall pooled analysis indicated that both two oral care modalities significantly reduced the risk of POP (RR, 0.60, 95% CI, 0.48–0.75; p < 0.001; I² = 49%) (Fig. 4).

Of the 16 observational studies, one evaluated chlorhexidine mouthwash. In that study, the incidence of POP was significantly lower in the chlorhexidine group (5, 2.6%) than in the control group (20, 10.5%), suggesting a protective effect (OR 0.22; 95% CI 0.08–0.61; p = 0.003). Among the 13 studies assessing mechanical cleaning, POP occurred in 1,445 patients (6.3%) in the POC group versus 3,192 (12.9%) in the control group. The subgroup meta-analysis showed that mechanical cleaning was associated with a reduced incidence of POP (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.39–0.45; p < 0.001). The two remaining studies adopted a combined approach, where POP developed in 5 patients (3.7%) in the POC group compared with 21 (16.2%) in controls, resulting in a significantly lower POP incidence (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.07–0.55; p = 0.002) with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%; p = 0.87). The overall pooled analysis indicated that all three oral care modalities significantly reduced the risk of POP (OR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.39–0.44; p < 0.001; I² = 40%) (Fig. 5).

Subgroup analyses regarding the concentration of chlorhexidine application (0.2% vs. 0.12%) revealed that both concentrations significantly reduced the risk of pneumonia (RR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.14–0.59; p = 0.0007 vs. RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35–0.79; p = 0.002) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Subgroup analyses of the frequency of chlorhexidine application (< 3 times vs. ≥ 3 times) revealed that both regimens significantly reduced the risk of pneumonia(RR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.20–0.73; p = 0.004 vs. RR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.45–0.89; p = 0.008) (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Subgroup analysis of different personnel-led oral care

Across 7 RCTs analyzing nurse-led oral care interventions, POP occurred in 104 patients (7.2%) in the POC group compared with 181 (9.1%) in the control group. POC was associated with a statistically significant reduction in POP (RR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.51–0.81; p < 0.001), with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 53%; p = 0.05) (Fig. 6). In the two remaining RCTs evaluating dental professional-led oral care, POP incidence was also lower in the POC group (8, 4.1%) versus controls (24, 12.2%). Meta-analysis confirmed a significant association between dental professional-led POC and reduced POP incidence (RR, 0.33, 95% CI, 0.15–0.72; p = 0.005), with no heterogeneity (I² = 0%; p = 0.83) (Fig. 6).

Among the observational studies, three reported POP in 10 patients (3.8%) receiving nurse-led POC versus 37 (14.6%) in control groups. Subgroup analysis demonstrated a protective effect of nurse-led POC against POP (OR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.11–0.46; p < 0.001), with no statistical heterogeneity (I² = 0%; p = 0.99) (Fig. 7). In the remaining 13 observational studies, POP occurred in 1,445 patients (6.3%) who received POC from dental professionals, compared with 3,196 (12.9%) in the control group. Dental professional-led POC was associated with a lower incidence of POP (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.39–0.45; p < 0.001). Low to moderate heterogeneity was observed (I² = 45%; p = 0.04) (Fig. 7).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 25 studies with a total of 52,227 patients to evaluate the impact of perioperative oral care on POP following thoracic surgery. Several key findings emerged. First, POP was observed to be a prevalent complication following thoracic surgery, with a cumulative incidence of about 12%. Second, all three oral care modalities—mechanical cleaning, chlorhexidine-based disinfection, and their combination—significantly reduced the risk of POP. Notably, chlorhexidine application demonstrated efficacy in risk reduction regardless of its concentration or administration frequency. Third, perioperative oral care, whether it was administered by nurses or dental professionals, significantly lowered the incidence of POP.

The human oral cavity harbors distinct microbial communities across its various niches, whereas the lower respiratory tract is typically sterile under healthy conditions26. Thoracic surgery confers elevated susceptibility to occult aspiration and facilitates bacterial translocation, attributable to the procedural proximity to the airways, routine requirement for general anesthesia, and impaired cough reflex secondary to postoperative pain27. As a relatively economical and convenient intervention, oral care eliminates pathogen-containing biofilms from various oral surfaces, enhancing patient hygiene and reducing the risk of POP17,28,29. However, the absence of definitive efficacy data from high-quality studies precludes a general recommendation for its use in current clinical guidelines. The study by Fu et al.30. demonstrates the significant efficacy of antibiotics in preventing pneumonia. However, their extensive and prolonged use is implicated in the emergence of highly resistant nosocomial infections and poses an additional economic burden31,32,33,34. Two meta-analyses of RCTs establish oral care as an effective intervention for preventing POP following cardiac surgery18,19. While a systematic review and meta-analysis associates oral care with reduced pneumonia risk across diverse non-cardiac surgeries (including various emergency, elective, and time-sensitive surgical procedures)21, evidence specific to thoracic surgery remains lacking. Our findings specifically establish perioperative oral care as protective against pneumonia in thoracic surgical patients.

Currently, no standardized protocol exists for perioperative oral care. The included literature primarily describes three modalities: mechanical cleaning, chemical disinfection, and a combined approach. Mechanical cleaning, such as brushing and swabbing, physically removes dental plaque, food debris, and biofilm, thereby reducing the microbial load. In contrast, chemical disinfection with agents like chlorhexidine offers broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity by disrupting bacterial cell membranes and inhibiting bacterial regeneration17,28,29. Our analysis provides valuable insights into the efficacy of different oral care methods. This study demonstrated that all three modalities—mechanical cleaning, chlorhexidine-based disinfection, and their combination—significantly reduced the risk of POP. Notably, the combined approach of mechanical cleaning and chlorhexidine-based disinfection exhibited a marginal advantage. This synergy operates through complementary actions: mechanical removal of biofilms followed by chemical suppression of residual planktonic bacteria, resulting in more effective and lasting microbial control. Nevertheless, prospective studies are needed to determine the optimal techniques, timing, and frequency of oral hygiene interventions. Subgroup analyses regarding the concentration and frequency of chlorhexidine application revealed that all regimens significantly reduced the risk of pneumonia, with the 0.2% concentration demonstrating a potentially superior effect. However, evidence suggests an association between chlorhexidine-based oral care and increased ICU mortality35,36, potentially mediated by oral microbiome depletion and reduced nitric oxide bioavailability37. Our study was underpowered to evaluate this risk, underscoring the need for future investigations to establish safe concentration, dosing, and duration of chlorhexidine use across patient populations.

The efficacy of nurse- or dental professional-led oral care currently remains inconclusive. Perioperative oral hygiene management conducted by dental specialists typically encompasses a comprehensive regimen, including dental calculus removal (scaling), oral health education, professional mechanical plaque removal, denture cleaning, tongue debridement with a brush, radiographic examination of suppurative sites, and evaluation of teeth for extraction in cases of severe periodontitis—particularly those presenting with pain, mobility, or significant alveolar bone loss38,39,40. Nurse-led oral care, involving either mechanical or chemical cleaning, primarily includes oral wiping with water and chemical disinfection using mouthwash, sprays, or broad-spectrum antiseptics such as chlorhexidine41,42,43. To compare these approaches, we performed a subgroup analysis of their effects on POP incidence. Our analysis demonstrates that POC is effective in reducing postoperative pneumonia, regardless of being delivered by ward nurses or dental specialists. This finding substantially enhances the feasibility and generalizability of POC implementation. Although POC delivered by dental professionals demonstrates superior efficacy in improving oral health outcomes compared to non-specialist care (e.g., basic toothbrushing or nurse-led protocols)44, it may entail higher operational complexity and resource costs21. In most healthcare settings, nurse-led oral care can be more readily integrated into standard perioperative workflows without requiring additional specialized staffing. This inherent practicality facilitates broader implementation and sustained adherence to the intervention across diverse clinical contexts. Nevertheless, these potential advantages require further investigation to be robustly validated.

While our findings are encouraging, several study limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, significant heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, notably originating from variations in patient comorbidities, specific surgical procedures (e.g., differing risks between lobectomy and esophagectomy), the oral care products used (e.g., concentration of chlorhexidine), and subtle differences in the diagnostic criteria for POP. Second, the 16 observational studies—13 of which were conducted in Japan—provide valuable real-world evidence, their findings remain susceptible to unmeasured confounders (e.g., baseline oral health and smoking history) and potential regional bias. Although the consistency observed across the 9 RCTs strengthens the validity of our conclusions, only one was assessed as high-quality. Therefore, future rigorously designed, large-sample randomized trials remain necessary to further corroborate these findings. Third, the current evidence remains insufficient to define the optimal timing, frequency, and duration of professional oral care, representing an important direction for future study. Finally, the included studies precluded comparative analysis of different perioperative oral care methodologies or provider types regarding postoperative outcomes, including length of hospital stay, mortality, and intervention-related side effects. This represents a critical avenue for future investigation.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides evidence that perioperative oral care serves as an effective strategy for reducing the incidence of postoperative pneumonia in patients undergoing thoracic surgery. The protective effect was consistently observed across various care methodologies and providers, with combined interventions potentially offering superior efficacy. Implementing standardized perioperative oral care protocols holds significant potential for improving patient outcomes and enhancing the overall quality of surgical care.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- POP:

-

postoperative pneumonia

- POC:

-

perioperative oral care

- RCTs:

-

randomized controlled trials

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- RR:

-

relative risk

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

References

Kazaure, H. S., Martin, M., Yoon, J. K. & Wren, S. M. Long-term results of a postoperative pneumonia prevention program for the inpatient surgical ward. JAMA Surg. 149, 914–918. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1216 (2014).

Wren, S. M., Martin, M., Yoon, J. K. & Bech, F. Postoperative pneumonia-prevention program for the inpatient surgical ward. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 210, 491–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.009 (2010).

Kataoka, K. et al. Prognostic impact of postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: Exploratory analysis of JCOG9907. Ann. Surg. 265, 1152–1157. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0000000000001828 (2017).

Farkas, E. A. & Detterbeck, F. C. Airway complications after pulmonary resection. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 16, 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.05.013 (2006).

Oparka, J., Yan, T. D., Ryan, E. & Dunning, J. Does video-assisted thoracic surgery provide a safe alternative to conventional techniques in patients with limited pulmonary function who are otherwise suitable for lung resection? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 17, 159–162. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivt097 (2013).

Andalib, A., Ramana-Kumar, A. V., Bartlett, G., Franco, E. L. & Ferri, L. E. Influence of postoperative infectious complications on long-term survival of lung cancer patients: A population-based cohort study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 8, 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182862e7e (2013).

Biere, S. S. et al. Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 379, 1887–1892. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60516-9 (2012).

Law, S., Wong, K. H., Kwok, K. F., Chu, K. M. & Wong, J. Predictive factors for postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality after esophagectomy for cancer. Ann. Surg. 240, 791–800. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000143123.24556.1c (2004).

Lee, J. Y. et al. Risk factors of postoperative pneumonia after lung cancer surgery. J. Korean Med. Sci. 26, 979–984. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2011.26.8.979 (2011).

Sandri, A. et al. Major morbidity after video-assisted thoracic surgery lung resections: A comparison between the European society of thoracic surgeons definition and the thoracic morbidity and mortality system. J. Thorac. Dis. 7, 1174–1180. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.06.07 (2015).

Ioanas, M. et al. Bronchial bacterial colonization in patients with resectable lung carcinoma. Eur. Respir J. 19, 326–332. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.02.00236402 (2002).

Cao, Y. et al. Oral care measures for preventing nursing home-acquired pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, Cd012416. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012416.pub3 (2022).

Akutsu, Y. et al. Impact of preoperative dental plaque culture for predicting postoperative pneumonia in esophageal cancer patients. Dig. Surg. 25, 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1159/000121903 (2008).

Marino, P. J. et al. Community analysis of dental plaque and endotracheal tube biofilms from mechanically ventilated patients. J. Crit. Care. 39, 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.02.020 (2017).

Hiramatsu, T., Sugiyama, M., Kuwabara, S., Tachimori, Y. & Nishioka, M. Effectiveness of an outpatient preoperative care bundle in preventing postoperative pneumonia among esophageal cancer patients. Am. J. Infect. Control. 42, 385–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2013.11.017 (2014).

Heo, S. M., Haase, E. M., Lesse, A. J., Gill, S. R. & Scannapieco, F. A. Genetic relationships between respiratory pathogens isolated from dental plaque and Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients in the intensive care unit undergoing mechanical ventilation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 47, 1562–1570. https://doi.org/10.1086/593193 (2008).

Munro, C. L. & Grap, M. J. Oral health and care in the intensive care unit: state of the science. Am. J. Crit. Care. 13, 25–33 (2004). discussion 34.

Bardia, A. et al. Preoperative chlorhexidine mouthwash to reduce pneumonia after cardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 158, 1094–1100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.01.014 (2019).

Spreadborough, P. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of perioperative oral decontamination in patients undergoing major elective surgery. Perioper Med. (Lond). 5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-016-0030-7 (2016).

Zhao, T. et al. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, Cd008367. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008367.pub4 (2020).

Liang, S., Zhang, X., Hu, Y., Yang, J. & Li, K. Association between perioperative chlorhexidine oral care and postoperative pneumonia in non-cardiac surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery 170, 1418–1431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2021.05.008 (2021).

Ljungqvist, O., Scott, M. & Fearon, K. C. Enhanced recovery after surgery: A review. JAMA Surg. 152, 292–298. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4952 (2017).

Feider, L. L., Mitchell, P. & Bridges, E. Oral care practices for orally intubated critically ill adults. Am. J. Crit. Care. 19, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2010816 (2010).

Higgins, J. P. et al. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj 343, d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928 (2011).

Melsen, W. G., Bootsma, M. C., Rovers, M. M. & Bonten, M. J. The effects of clinical and statistical heterogeneity on the predictive values of results from meta-analyses. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12494 (2014).

Martin-Loeches, I. & Torres, A. Are preoperative oral care bundles needed to prevent postoperative pneumonia? Intensive Care Med. 40, 109–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3081-y (2014).

El-Rabbany, M., Zaghlol, N., Bhandari, M. & Azarpazhooh, A. Prophylactic oral health procedures to prevent hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 52, 452–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.07.010 (2015).

Akutsu, Y. et al. Pre-operative dental brushing can reduce the risk of postoperative pneumonia in esophageal cancer patients. Surgery 147, 497–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.048 (2010).

Sato, Y. et al. Esophageal cancer patients have a high incidence of severe periodontitis and preoperative dental care reduces the likelihood of severe pneumonia after esophagectomy. Dig. Surg. 33, 495–502. https://doi.org/10.1159/000446927 (2016).

Farran, L. et al. Efficacy of enteral decontamination in the prevention of anastomotic dehiscence and pulmonary infection in esophagogastric surgery. Dis. Esophagus. 21, 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00764.x (2008).

Diallo, O. O. et al. Antibiotic resistance surveillance systems: A review. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 23, 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2020.10.009 (2020).

Liu, C. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in South korea: A report from the Korean global antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (Kor-GLASS) for 2017. J. Infect. Chemother. 25, 845–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2019.06.010 (2019).

Prestinaci, F., Pezzotti, P. & Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog Glob Health. 109, 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047773215y.0000000030 (2015).

Solomon, S. L. & Oliver, K. B. Antibiotic resistance threats in the united states: Stepping back from the Brink. Am. Fam Physician. 89, 938–941 (2014).

Deschepper, M., Waegeman, W., Eeckloo, K., Vogelaers, D. & Blot, S. Effects of chlorhexidine gluconate oral care on hospital mortality: A hospital-wide, observational cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 44, 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5171-3 (2018).

Klompas, M., Speck, K., Howell, M. D., Greene, L. R. & Berenholtz, S. M. Reappraisal of routine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patients receiving mechanical ventilation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 174, 751–761. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.359 (2014).

Blot, S. Antiseptic mouthwash, the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway, and hospital mortality: A hypothesis generating review. Intensive Care Med. 47, 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06276-z (2021).

Soutome, S. et al. Prevention of postoperative pneumonia by perioperative oral care in patients with esophageal cancer undergoing surgery: A multicenter retrospective study of 775 patients. Support Care Cancer. 28, 4155–4162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05242-w (2020).

Soutome, S. et al. Preventive effect on Post-Operative pneumonia of oral health care among patients who undergo esophageal resection: A Multi-Center retrospective study. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt). 17, 479–484. https://doi.org/10.1089/sur.2015.158 (2016).

Soutome, S. et al. Effect of perioperative oral care on prevention of postoperative pneumonia associated with esophageal cancer surgery: A multicenter case-control study with propensity score matching analysis. Med. (Baltim). 96, e7436. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000007436 (2017).

Caparelli, M. L. et al. Prevention of postoperative pneumonia in noncardiac surgical patients: A prospective study using the National surgical quality improvement program database. Am. Surg. 85, 8–14 (2019).

D’Journo, X. B. et al. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal decontamination with chlorhexidine gluconate in lung cancer surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 44, 578–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5156-2 (2018).

Semenkovich, T. R. et al. Postoperative pneumonia prevention in pulmonary resections: A feasibility pilot study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 107, 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.08.008 (2019).

Yamada, Y. et al. The effect of improving oral hygiene through professional oral care to reduce the incidence of pneumonia Post-esophagectomy in esophageal cancer. Keio J. Med. 68, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.2302/kjm.2017-0017-OA (2019).

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Lingyan Duan and Donglin Li have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship. The first draft of the manuscript was written by L.D. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All other authors have contributed to project conception, checking raw data, revising, editing and approving the manuscript in its entirety. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, L., Li, D., Li, Z. et al. Effect of perioperative oral care on postoperative pneumonia in thoracic surgery patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 16, 951 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30492-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30492-6