Abstract

In response to the frequent occurrences of urban surface collapse in fluvial alluvial plains, this study takes the collapse event on Changfeng Road in the Binjiang Plain area of Anqing City as a typical case. Through scaled physical model experiments and mechanical response analysis, the stress transfer patterns of the soil surrounding defective pipelines and the chain-evolution mechanism of collapse disasters are systematically investigated. The results indicate that the essence of pipeline-induced collapse lies in the progressive structural instability of soil caused by seepage-induced erosion. The dynamic evolution of erosion cavities—including their formation, expansion, and eventual breakthrough—is identified as the dominant mechanism leading to sudden surface collapse. Stress evolution displays spatial variability: vertically, layers nearer to the leak exhibit greater stress reduction and disturbance compared to overlying strata; horizontally, disturbance diminishes radially from the collapse center, accompanied by delayed stress release in peripheral zones. Pore water pressure dynamics are controlled by seepage forces and hydraulic gradients, with sharp variations near the leak point signaling imminent instability. Groundwater flow promotes soil skeleton weakening, particle transport, and collapse channel development. The morphology of the collapse evolves through three stages: truncated cone, truncated cone + conical body, and conical body, all of which display significant precursors and characteristics of instability prior to surface collapse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advancement of urbanization in China, incidents of urban ground collapse have become increasingly frequent in areas of intensive human activity1,2. Between 2010 and 2020, more than 3200 urban ground collapse events were recorded nationwide3, with river alluvial plains identified as the primary affected regions (Fig. 1a). These areas, due to their unique geological settings and concentrated urban development4, face growing geohazard risks under increasing demands for population concentration and underground space utilization5. Urban ground collapse is marked by concealment, sudden onset, and chain reactions. Its formation process is often accompanied by secondary disasters such as pipeline rupture and subway water inrush, posing significant threats to urban infrastructure, transportation networks, and public safety. An analysis of 354 documented collapse cases6 with identified causes shows that the disaster-inducing factors can be categorized into six groups: pipeline leakage7, engineering construction, rainfall, geological conditions, groundwater8, and other factors (Fig. 1b). Notably, drainage pipeline leakage accounts for 164 cases (46.3%), making it the predominant cause. This trend is particularly pronounced in river alluvial plains, largely due to the coupling effect of widely distributed shallow-buried drainage networks and special geological structures in these areas. Given these characteristics, systematic research into the collapse mechanisms of shallow-buried drainage pipelines in river alluvial plains holds significant practical value. Uncovering the spatiotemporal evolution of soil erosion and piping caused by pipeline leakage, as well as the resulting stress redistribution and structural instability in the soil, is of critical scientific importance for establishing a robust urban geohazard prevention and control system.

Urban ground collapse often occurs beneath paved surfaces, and its evolution process is difficult to observe directly due to its concealed nature9. Significant technical challenges remain, particularly in identifying pipeline leakage points and monitoring the entire process from initiation to progression and eventual disaster10. Current research primarily relies on two technical approaches: physical model tests 11,12,13 and numerical simulations14,15,16. In the field of numerical simulation, Ibrahim17 employed a coupled computational fluid dynamics and discrete element method to systematically reveal the quantitative influences of groundwater level, crack size, and pipeline defect angle on the seepage-induced erosion process. Tan and Long18 innovatively developed a coupled seepage-DEM model, successfully simulating stress redistribution characteristics in sandy soil around seepage tunnels and proposing a generalized stress arch theory model. Using the finite difference software FLAC, Wang19 investigated the meso-mechanisms of pipeline leakage, providing a systematic analysis of changes in seepage forces, effective stress, and earth pressure on pipelines during leakage. However, the core issue of ground collapse induced by underground pipeline leakage lies in the complex interaction between soil and fluid, where traditional numerical methods exhibit certain limitations. For instance, the finite element method20 treats soil as a continuum, making it difficult to accurately capture particle movement and failure behavior; the discrete element method21 focuses on particle motion but falls short in accurately describing fluid behavior; while the finite difference method22 also has shortcomings in simulating nonlinear behaviors. In summary, numerical simulations of pipeline leakage-induced ground collapse are constrained by their respective theoretical frameworks, making it challenging to fully and intuitively reproduce dynamic processes such as particle migration, transport, and evolution of contact states under seepage erosion—particularly given the highly nonlinear and complex nature of soil-fluid coupling.

Given the limitations of numerical simulations and the specific characteristics of pipeline leakage and erosion processes, physical model testing serves as a practical tool for studying pipeline-induced collapse. Such tests have been widely used to simulate underground pipeline leakage scenarios, enabling real-time observation of internal soil structure changes, water flow path evolution, particle loss and redistribution, and the dynamic process of instability and collapse23,24. For example, Mukunoki25 used X-ray scanning technology to observe the role of groundwater in cavity formation under both inflow and drainage conditions. The study found that groundwater flow through defective zones loosens the soil, allowing particles to migrate into the pipeline and leading to instability in the overlying strata. Alsaydalani26, through two-dimensional pipeline leakage tests, clarified the fluidization state of soil due to internal groundwater flow and noted that ground collapse typically occurs within a certain conical range, highlighting the spatial control of groundwater seepage on collapse extent. Liu27 synthesized results from laboratory model tests to analyze the effects of outlet size, location, pipeline pressure, and burial depth on soil erosion and ground collapse, finding that soil fluidization occurs when the ratio of water pressure head to burial depth exceeds 2. Zoueshtiagh9, through laboratory experiments, divided the process of soil erosion by groundwater into three stages: steady seepage, hole formation, and full fluidization, clarifying the role of groundwater in each stage.

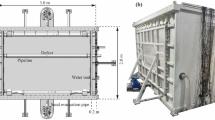

However, most current physical model studies on pipeline leakage-induced collapse use small-scale two-dimensional (2D) models with a bottom opening to simulate pipeline leaks, as shown in Fig. 2. For instance, Tan28 constructed a physical model tank made of transparent plexiglass, measuring 1 m long, 0.2 m wide, and 0.8 m high, with pre-drilled holes on the sides to simulate underground pipelines, reproducing the dynamic process of progressive collapse induced by pipeline damage. Indiketiya29 built a test setup using transparent acrylic plates with dimensions of 0.8 m × 0.1 m × 0.4 m, simulating leakage-induced collapse mechanisms using dual water tanks and a bottom opening. Nevertheless, underground pipeline leakage-induced collapse is inherently a three-dimensional (3D), multi-physical-field coupled process, and existing small-scale 2D models have notable limitations 30,31,32. First, the 2D design cannot accurately reflect the spatial gradient distribution of seepage and stress fields in prototypical strata, leading to distortions in geometric similarity of seepage paths and 3D expansion patterns of erosion cavities, thereby deviating predictions of collapse extent and surface settlement rates from actual observations. Second, the use of a bottom opening simplifies pipeline leakage into a unsteady seepage boundary condition, neglecting the coupling between sediment transport and water flow erosion within the pipeline—particularly the effect of sand accumulation on seepage paths and its role in regulating collapse rates.

In light of the limitations of current physical model test setups, this study developed a large-scale physical model test platform based on similarity theory, with a collapse model tank as the core, integrated with systems for fluid control and monitoring. This platform more closely approximates real conditions in terms of model size, pipeline structure, and internal sediment accumulation characteristics, effectively reducing adverse size effects and realistically reproducing the complex hydrodynamic environment inside pipelines. By recreating the entire process of ground collapse induced by pipeline leakage, the experiment enables systematic analysis of the dynamic evolution of soil displacement, collapse morphology, stress distribution, pore water pressure, and other deformation and mechanical characteristics, revealing the formation and evolution mechanisms of ground collapse. This study can provide detailed experimental data and reliable theoretical support for interpreting the disaster mechanisms of shallow buried defective pipelines and building prediction and early warning systems, offering important scientific value and practical engineering significance for enhancing urban disaster prevention and mitigation capabilities and achieving precise risk control.

Methods and materials

Engineering background

Anqing City is located in the southwestern part of Anhui Province and sits along the northern bank of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, occupying a key position along this “golden waterway.” As one of the ten major port cities on the Yangtze River and an important node in the Yangtze River Delta urban agglomeration (Fig. 3), Anqing plays a significant strategic role in regional development. The regional geomorphology exhibits a stepped transition pattern, gradually descending in elevation from northwest to southeast. It comprises three main geomorphic units: the middle–low mountainous areas of the Dabie Mountains, the Tongqian red bed basin, and a low hill–plain composite zone along the Yangtze River. This topographic configuration results in a progressively declining elevation from inland to riverfront areas. In the riverfront plain zone, the phreatic water table is shallow, ranging from 0.5 to 2 m below the surface. The confined aquifer system is characterized by a dual-layered sandy structure. The first sand layer has a top depth of 0.7–5.7 m and a thickness of 1.95–16.5 m, while the second layer lies at a depth of 20.0–34.45 m with a thickness of 4.2–11.0 m. These loose sandy strata, with high permeability and poor structural stability, are highly susceptible to seepage-induced erosion and represent high-risk zones for ground collapse.

In April 2019, a typical ground collapse event occurred in the central section of Changfeng Road, Yingjiang District, Anqing City, resulting in a collapse pit approximately 30 m² in area and 1.5 m in depth (Fig. 4). On-site investigation revealed classic morphological features of ground collapse: a void structure formed beneath the pavement due to separation between the pavement layer and the subgrade, large areas of exposed subgrade soil, tensile cracks appearing on the sidewalk, and significant tilting of trees in the adjacent greenbelt. Root cause analysis indicated that a structural failure occurred in a sewage pipeline located approximately 8 m beneath the road surface, with a diameter of 1 m. Driven by the pressure differential between the inside and outside of the pipeline, groundwater continuously carried sand particles through the damaged section into the pipe, resulting in progressive internal erosion of the overlying soil. As the water–soil loss persisted, the cavity above the pipeline gradually expanded, ultimately forming a subsurface void that led to the collapse of the overlying pavement due to loss of structural support.

Test design and materials

To simulate the formation mechanism of ground collapse and investigate the coupled water–soil interaction process, a physical model box was designed based on similarity principles to replicate collapse induced by defective underground pipelines33. The physical modeling platform consists of three components: a monitoring system, a water level control system, and the main test model box (Fig. 5).

The external steel frame of the model box measures 3 m × 2 m × 2 m. A high-strength transparent acrylic panel is installed on the front side to facilitate visual observation and monitoring of the collapse process caused by pipeline defects. A 100 mm diameter acrylic pipe is embedded within the box to simulate the drainage pipeline, with a 20 mm diameter circular hole drilled at the top center of the pipe to represent a structural defect. The monitoring system comprises sensors and industrial cameras. Earth pressure sensors and pore water pressure sensors are used to record the mechanical and hydraulic responses during the collapse process, while industrial cameras capture the real-time evolution of surface deformation and failure. The water level control system consists of two subsystems: groundwater control and internal pipe flow control. The groundwater control system incorporates various devices, including a water level control tank, permeable baffles, and permeable structures (Fig. 6). By maintaining a stable water level difference on both sides of the model, a controllable hydraulic gradient is established within the soil, thereby indirectly regulating the seepage velocity and flow rate. The internal pipe flow control system is composed of a water supply source, a water pump, a storage water tank, and braided hoses (Fig. 7). Throughout the test, the pipe maintains a free-surface flow condition, which prevents the accumulation of soil particles inside the pipeline. This is critical, as such accumulation could obstruct the seepage and erosion processes.

The similarity coefficients for key physical quantities were determined by comprehensively considering experimental feasibility, measurement accuracy, and cost, guided by similarity theory and dimensional analysis34,35. Based on the fundamental ratios of geometry (\({C}_{L}=10\)), density (\({C}_{y}=1\)), and gravitational acceleration (\({C}_{g}=1\)), the similarity constants for other parameters were derived. This resulted in a stress similarity ratio of \({C}_{\sigma }={C}_{\gamma }\cdot {C}_{L}=10\), a displacement similarity ratio of \({C}_{\delta }={C}_{L}=10\), and a permeability coefficient similarity ratio of \({C}_{k}=\sqrt{{C}_{L}\cdot {C}_{g}}={10}^{1/2}\). Crucially, to ensure mechanical and hydraulic similarity, the internal friction angle and Poisson’s ratio were governed by the similarity ratios \({C}_{\varphi }=1\) and \({C}_{\mu }=1\). This approach ensures that the model replicates the key physical and mechanical responses of the prototype under seepage-erosion conditions.

Ibrahim and Meguid pointed out that collapse induced by pipeline leakage predominantly occurs in sandy soils17. This is because, compared with loose, non-cohesive soils, cohesive soils tend to maintain structural integrity under seepage forces and are less susceptible to continuous erosion. In experimental studies on ground collapse triggered by pipeline leakage, researchers such as Dai36, Tang37, and Ren38 have innovatively adopted quartz sand as the test material, successfully achieving high precision and reproducibility in experimental data, thereby providing a reliable material basis for related research. The selection of quartz sand was based on the following advantages: (1) stable physical properties, ensuring high repeatability and accuracy of the experiments; (2) mechanical behavior close to that of natural sand layers, allowing for realistic simulation of soil responses under loading, deformation, and shear failure; (3) excellent permeability, especially under saturated conditions, resembling the flow characteristics of natural aquifers; and (4) high controllability, as particle shape, size, and density can be precisely adjusted through sieving and processing.

In physical model tests of underground pipeline leakage-induced collapse, selecting analogous materials that closely match the properties of the actual stratum is critical. According to similarity theory, the model materials must replicate key mechanical and physical parameters of the prototype stratum. However, during practical mixture design, theoretical calculations alone are often insufficient to achieve optimal material performance, and adjustments targeting crucial parameters are generally required based on experimental objectives. This study focuses on the deformation response, mechanical characteristics, and evolution mechanism of ground collapse induced by pipeline leakage, and therefore places particular emphasis on the similarity of the internal friction angle and void ratio39. Laboratory tests were conducted to measure the dry density, void ratio, internal friction angle, and angle of repose of quartz sand. The results show that the internal friction angle and void ratio of the model material correspond well with those of the prototype soil, ensuring that the model accurately captures the mechanical and hydraulic behavior of the prototype under similar conditions. The basic physical properties of the quartz sand used in this study are shown in Table 1, and the material appearance and particle size distribution are presented in Fig. 8.

Test schemes and procedures

The implementation of physical model tests on ground collapse induced by pipeline leakage is a comprehensive research process involving large-scale setups, extended testing durations, and multidisciplinary collaboration40. The experimental workflow primarily includes equipment inspection and system integration, water-tightness testing, material placement, sensor installation, water level control, seepage-induced erosion, and data recording, as illustrated in Fig. 9.

The main procedures are as follows:

-

(1)

Instrument inspection and system integration.

Prior to the test, the experimental material was filled into the test platform in batches using a sand-filling system (Fig. 9d). To ensure stratum homogeneity, each 10 cm layer was compacted, and the surface of every soil layer was roughened to minimize stratification and improve filling quality and test reliability (Fig. 9e). The uniformity of compaction density throughout the model was further verified by the consistency of initial sensor readings across different layers and locations.

-

(2)

Material placement.

Before testing, the experimental sand was incrementally placed into the model tank using a sand-filling system (Fig. 9d). To ensure stratigraphic uniformity, each 10 cm layer was compacted and the surface was roughened using a wire brush before adding the next layer (Fig. 9e), minimizing interlayer discontinuities and improving filling quality and experimental reliability.

-

(3)

Monitoring device installation.

During material filling, the monitoring system was installed strictly according to the experimental design. A set of earth pressure (E1) and pore water pressure (P1) sensors was placed 1 cm above the defect point (Fig. 9f), with their parameters provided in Table 2. Additional sensor groups were positioned at vertical depths of 11 cm (E2/P2), 31 cm (E3/P3), 51 cm (E4/P4), and 71 cm (E5) within the stratum (Fig. 10a). Additionally, at the same elevation level of 51 cm (E3/P3), sensors were installed at different radial positions to analyze the distribution and evolution of vertical stress along the horizontal direction (Fig. 10b). All sensor cables were routed out from the top of the model tank and securely connected to a data acquisition system. Furthermore, a 2D industrial camera (specifications listed in Table 3) was mounted outside the transparent acrylic observation window, precisely calibrated to capture high-resolution imagery of the collapse evolution process (Fig. 9h).

-

(4)

Water level control.

To maintain stable groundwater conditions during the experiment, water was introduced into the collapse model tank in stages via the water level control system. After each 10 cm rise in water level, a 30-minute settling period was applied to allow the soil to adjust, minimizing the risk of localized erosion or uneven settlement caused by rapid water level increases. This approach ensured overall stratigraphic stability and uniform saturation of the soil.

-

(5)

Pipe defect and erosion process.

As per the test protocol, a pipe leakage scenario was simulated by removing a pre-installed 20 mm rubber plug from the top of the buried pipe (Fig. 9g). This method minimized disturbance to the surrounding soil. Upon initiation of the leakage, the industrial camera system was activated to continuously capture images at a preset sampling frequency of 3 Hz, ensuring a complete visual record of the soil collapse process. During the experiment, a DM-YB1860 high-precision data acquisition system was used to monitor stress evolution in both vertical and horizontal directions. Data collection continued until no further sand movement was observed within the defective pipe, which marked the end of the test.

Test results and analyses

Stress evolution analysis

Vertical stress

In the present study, both earth pressure and pore water pressure data are presented as changes relative to the initial stable state. This normalized representation emphasizes the dynamic variations and transfer mechanisms of stress and pore pressure during collapse, rather than reflecting absolute values or implying the development of tensile stress. The experimental stress evolution exhibited a clear three-stage pattern: seepage erosion, cavity expansion, and collapse stabilization (Fig. 11). Initially, the vertical stress field remained relatively balanced; however, it soon entered a phase of rapid stress decline, eventually reaching a new equilibrium through self-organizing adjustment. Monitoring data revealed a cascading stress response: the primary sensor E1 recorded a sudden drop of -8.04 kPa within 1.67 s, followed by fluctuations stabilizing at -9.62 kPa after 462 s. Secondary sensors E2 and E3 peaked at -13.79 kPa and − 12.21 kPa at 1.83 and 2.50 s, respectively; E2 gradually rebounded to -8.66 kPa over 768 s, while E3 rose slowly to -11.72 kPa. Terminal sensors E4 and E5 reached − 7.13 kPa and − 3.53 kPa between 4.6 and 6.27 s before stabilizing. At equilibrium, the stress field showed a distinct gradient distribution: E1 (-9.24 kPa), E2 (-13.67 kPa), E3 (-11.72 kPa), E4 (-5.33 kPa), and E5 (-1.28 kPa), illustrating the spatial attenuation characteristics of soil structure degradation.

According to multiphase flow theory, the seepage drag force is positively correlated with particle size under both laminar and turbulent flow conditions 41,42. However, during the initial stage of erosion, the migration of coarse particles is constrained due to their larger size and the limited pore space within the skeleton, resulting primarily in minor adjustments of the granular framework (Fig. 12a). Instead, fine particles within the soil matrix are transported through the pore network formed by the coarse skeleton toward the pipeline system. This process leads to the loosening of the soil structure and a reduction in soil strength, a phenomenon particularly pronounced in poorly graded coarse-grained soils. This mechanism of internal erosion, characterized by the selective loss of fine particles, constitutes the initial phase of soil structural deterioration (Fig. 12b). As seepage continues, the alteration of the soil structure due to fine particle migration creates preferential flow paths and seepage channels. A concentrated seepage zone with high hydraulic gradients forms near the pipeline, while the far-field region maintains a relatively uniform seepage field. When the loss of fine particles reaches a critical threshold, the geometrical stability of the coarse particle skeleton undergoes fundamental changes. Coarse particles begin to migrate toward structural defects under the coupled effects of seepage force and gravity (Fig. 12c), leading to the progressive development of an erosion cavity within the soil stratum.

This phenomenon reveals a three-stage evolution mechanism of soil failure. In the initial seepage stage, the soil mass remains in static equilibrium as long as the seepage force does not exceed the interparticle forces and self-weight. As groundwater level fluctuations lead to the expansion of seepage channels, the increasing seepage force induces fine particle migration and internal erosion. Once the leakage volume exceeds a critical threshold, concealed cavities begin to form and expand near the defect zone, while the ground surface remains seemingly stable. Eventually, the overlying strata lose support, triggering surface collapse. The disturbance is most prominent near the defect but has a limited influence range. This process highlights that progressive structural destabilization due to seepage-induced erosion is the essence of the disaster. Moreover, the dynamic evolution of the erosion cavity—including its formation, expansion, and breakthrough—is the dominant mechanism leading to sudden surface collapse in cases of pipeline leakage.

Spatial distribution of vertical stress along the horizontal plane

As shown in Fig. 13, the evolution of vertical stress distribution in the horizontal plane exhibits distinct spatial patterns. Monitoring point E3, located at the collapse core, experienced a sharp stress drop from the initial value (0 kPa) to -12.21 kPa within 2.50 s, eventually stabilizing at -11.72 kPa. In contrast, peripheral monitoring points E6, E7, and E8—positioned 25 cm from the collapse center—showed a delayed response, with stress gradually decreasing in a fluctuating manner to a stable value of -6.76 kPa. Experimental results indicate that during collapse development, saturated sand in the overlying layer continuously migrated toward the pipeline under seepage forces, forming a conical deposition body. Due to the relatively low sand loss rate in peripheral zones, the magnitude of stress reduction (Δ5.45 kPa) was significantly smaller than that in the core region (Δ11.72 kPa), confirming a negative correlation between soil disturbance intensity and distance from the collapse center in the horizontal direction. Furthermore, liquefaction phenomena were confined within the conical influence zone induced by the pipeline defect, while the soil outside the cone remained static, highlighting the spatially constrained nature of collapse propagation.

Pore water pressure evolution analysis

During the collapse process, the soil stress field and pore water pressure field exhibited significant time-dependent coupling characteristics. Based on the staged division from the soil stress evolution analysis—namely the seepage erosion phase, cavity expansion phase, and collapse development phase—a detailed analysis of the pore water pressure was conducted. This analysis effectively revealed how the variation in groundwater seepage pressure gradients under the coupled action of seepage and erosion in each phase drives the weakening of the soil skeleton, the migration of soil particles, and the formation of collapse channels.

The evolution of pore water pressure within the strata is shown in Fig. 14. Results indicate that during the seepage erosion phase, pore water pressure at various monitoring points exhibited a progressive accumulation trend with increasing radial distance from the leakage point, reaching peak values of 0.121 kPa, 0.053 kPa, 0.027 kPa, and 0.021 kPa, respectively. This phenomenon reveals the dynamic formation of an asymmetric seepage field driven by the hydraulic head gradient near the leakage opening, as groundwater gradually permeates through the soil pore network. The steady increase in pore water pressure during this phase suggests that groundwater flow reconstructs localized hydraulic gradients and adjusts the pore structure of the soil, progressively establishing a preferential seepage path centered around the leakage point.

In the cavity expansion phase (Fig. 15a), a pressure drop was first observed at P4, followed sequentially by P3, P2, and P1, indicating a cascading response. At this stage, intensified seepage near the leakage point leads to erosion of the coarser soil skeleton and the formation of localized shear failure zones (Fig. 15b). Continued erosion and particle migration around the leakage point result in progressive collapse of the overlying soil, with larger declines in pore water pressure observed in strata closer to the pipe (Fig. 15c).

During the collapse development phase, pore water pressure gradually stabilized and slightly rebounded. As the erosion process reached saturation, the soil structure achieved a relatively stable condition. Particle loss diminished, the scouring effect of the flow weakened, and pore water pressure ceased to fluctuate drastically, instead trending toward equilibrium. In the eroded soil structure, water could pass freely through enlarged pores, enabling partial recovery of pore pressure. However, due to the loosened nature of the soil, the pressure could not return to the higher levels observed during the initial seepage phase.

Displacement characteristics analysis

After the experiment, the VDD raw data captured by the industrial camera was decoded using the professional strain analysis software VDAStrainAnalyzer, successfully reconstructing 7732 high-resolution grayscale digital image frames43. By applying temporal analysis methods, cross-correlation calculations and displacement field reconstruction were performed on the multi-temporal image sequence obtained throughout the experiment. This enabled millimeter-scale dynamic tracking of the motion trajectories of sand particles. The process is illustrated in Fig. 16.

To investigate the variation patterns of soil displacement during underground pipeline leakage-induced collapse, industrial cameras were employed to monitor the evolution of surface settlement width and depth over time, as shown in Fig. 17. During the seepage phase (0–370 s), fine particle migration occurred within the soil, while no visible surface deformation was observed. As seepage continued into the erosion phase, the underground cavity expanded rapidly. At 380 s, a critical instability emerged on the surface, forming a collapse pit with a width of 18.49 cm and a depth of 5.96 cm. Between 381 and 431 s, the displacement rate increased significantly, and by 431 s, the collapse width reached 46.27 cm with a depth of 20.62 cm. Although the expansion rate slowed thereafter, both width and depth continued to increase. Driven by seepage erosion, soil particles near the leakage point migrated into the pipeline, causing progressive surface collapse. The strong erosive effect of the water flow gradually weakened the soil structure around the pipeline, leading to further expansion of the collapse area. By the end of the erosion phase, the surface collapse reached a width of 98.6 cm and a depth of 47.1 cm.

As the evolution entered the collapse development stage, the migration of soil particles reached a dynamic equilibrium, and the rate of collapse expansion began to slow down. By 2648 s, the surface collapse width stabilized at 118.84 cm, and the collapse depth reached 57.99 cm. With the progressive saturation of soil particle loss, the scouring effect of water flow weakened, and the collapse above the damaged pipeline gradually reached a stable state, ceasing further expansion. The entire displacement evolution process clearly illustrates the geological disaster progression—from concealed particle migration to sudden structural instability, and ultimately to dynamic equilibrium. This sequence reveals significant precursor signals and instability characteristics associated with surface collapse events.

Collapse morphology evolution

Through temporal analysis of 7732 grayscale digital images captured during the collapse process, the morphological evolution of the collapse zone can be divided into three distinct stages: truncated cone (Fig. 18), truncated cone + conical shape (Fig. 19), and conical shape (Fig. 20). At the onset of surface collapse, the collapse initially forms a shape resembling a truncated cone. At this stage, seepage-induced erosion is still in its early phase, and the subsurface structure retains a certain degree of support, resulting in a relatively regular and stable collapse area. As seepage erosion intensifies, the bottom of the collapse zone begins to expand. The base of the originally trapezoidal structure is gradually eroded into a concave form, creating a conical base. The collapse area thus develops into a composite morphology, with a truncated cone at the top and an expanding conical shape at the bottom. During this stage, the soil structure becomes further weakened, and the scouring effect of water penetrates deeper layers, accelerating particle migration.

Based on the dynamic evolution characteristics of collapse morphology and surface geometric parameters (collapse width and depth), the evolution of erosion volume induced by underground pipeline leakage is shown in Fig. 21. During the erosion stage, an observable collapse first appears at 380 s, corresponding to a collapse volume of 1018.38 cm3. In this stage, seepage erosion causes continuous scouring of the soil around the pipeline, carrying away a large number of soil particles and leading to a sharp increase in volume loss. As the coupled seepage-erosion process continues to undermine the soil skeleton structure, the collapse volume reaches 16351.81 cm3 by the end of the erosion stage at 1250 s. In the stabilization stage, the rate of particle loss begins to slow down and gradually reaches saturation, with the final collapse volume stabilizing at approximately 214302.28 cm3. During this phase, the erosive action of water weakens, the rate of soil particle loss decreases, and the volume loss curve gradually levels off.

In summary, the progressive destabilization of the soil structure caused by seepage erosion during underground pipeline leakage-induced ground collapse is the essence of this disaster, while the dynamic evolution of erosion cavities—including their formation, expansion, and breakthrough—is the primary mechanism leading to sudden surface collapse. In the early stage of seepage erosion, groundwater gradually infiltrates through the soil’s pore network, causing fine particles to migrate under seepage forces, which leads to subtle changes in the internal pore structure of the soil. With the continued action of seepage forces, the soil skeleton is progressively weakened, and micro erosion cavities begin to form in localized areas near the leakage outlet. As the process enters the erosion stage, seepage forces further intensify, causing rapid expansion of the erosion cavities, destruction of the coarse particle skeleton, and continuous enlargement of the cavity area. When the cavities expand to a certain extent, the overlying soil loses support, resulting in overall soil structure instability and ultimately causing sudden surface collapse.

Discussion

The formation mechanism of urban ground collapse in river alluvial plain areas exhibits significant stratigraphic dependence. The typical sedimentary layers in this region are dominated by fluvial and floodplain sands, characterized by high permeability and shallow groundwater, resulting in underground pipelines generally being situated in saturated seepage environments. When sewer networks age and become damaged, groundwater carries saturated sandy soil to form piping channels, leading to progressive soil loss and ultimately causing collapse. In comparison, although water supply pipeline damage may trigger sudden collapse events, because the internal water pressure is consistently higher than the surrounding groundwater pressure, significant collapse typically only occurs when pre-existing concealed voids (such as karst conduits or mined-out areas) are present. The hazard’s concealment and risk of ongoing development are thus lower than those associated with sewer systems.

Experimental findings reveal that the collapse evolution exhibits distinct dual-structure characteristics (Fig. 22). Below the groundwater table, a conical erosion zone (AO segment) controlled by seepage-gravity coupling forms, whose expansion angle α is jointly determined by the underwater repose angle of sandy soil and seepage velocity; above the water table, a vertical shear failure surface (CO segment) forms, where stress release triggers soil self-weight instability, showing typical dry sand collapse characteristics. It is noteworthy that the mechanism of collapse expansion revealed in this experiment within a homogeneous sand layer—namely, the development of seepage-dominated inverted conical erosion channels followed by stress redistribution and shear failure—provides important insights for understanding the disaster chain mechanism in more complex multi-layered stratum systems. We hypothesize that in natural multi-layered strata, this process may evolve progressively: highly permeable sand layers are likely to form preferential erosion channels first, thereby triggering instability in the overlying strata. If the overlying layer consists of water-softened strata (such as collapsible loess), it may accelerate the vertical propagation of collapse; conversely, if the overlying layer is structurally stable, it may form a natural stopping mechanism. Therefore, the spatial coupling effect of stratigraphic permeability differences and groundwater dynamic conditions may be the core factor controlling the actual collapse development pattern. The findings of this study suggest that when conducting disaster risk assessments in alluvial plain areas, attention should be paid to the spatial distribution characteristics of the stratigraphic structure, particularly the interface positions between highly permeable sand layers and water-sensitive soft strata. These key parameters theoretically determine the development of preferential erosion pathways and the final scale of collapse. This preliminary understanding points the way for subsequent research on multi-layered systems and provides a theoretical analytical framework for urban underground space safety evaluation.

Conclusions

Based on the typical geological environmental characteristics of alluvial plain areas—using the dynamic coupling system formed by highly permeable alluvial-diluvial strata and shallow groundwater as the background—this study investigates the disaster mechanisms induced by subsurface pipeline leakage, with an empirical analysis of a typical collapse case on Changfeng Road in the riparian plain area of Anqing City. By establishing a scaled physical model test platform, the dynamic evolution patterns of mechanical and deformation features—such as earth pressure, pore water pressure, displacement, and collapse morphology—during the process of collapse triggered by defective pipelines were systematically analyzed. The mechanism of progressive failure in soil structure under the influence of groundwater seepage was clarified. The results indicate:

-

(1)

The progressive instability of soil structure resulting from seepage-induced erosion is the fundamental cause of disasters during pipeline leakage-induced collapse. The dynamic evolution of erosion cavities—including their formation, expansion, and interconnection—serves as the dominant mechanism leading to sudden ground collapse.

-

(2)

Stress evolution during collapse exhibits spatial differentiation: vertically, strata near the leakage point experience more significant stress reduction due to direct leakage effects, leading to higher disturbance intensity compared to overlying layers; horizontally, soil disturbance intensity decreases with distance from the collapse center, and peripheral regions show a noticeable hysteresis effect in stress release.

-

(3)

Groundwater seepage drives the weakening of the soil skeleton, particle migration, and the formation of collapse channels.

-

(4)

The evolution of collapse morphology displays stage-specific geometric characteristics, transitioning from a truncated cone form, to a combination of truncated cone and cone, and finally to a conical shape. Quantitative analysis measured the surface collapse width at 118.84 cm, depth at 57.99 cm, and final volume at 214,302.28 cm3.

-

(5)

The collapse evolution demonstrates distinct dual-structure characteristics: below the groundwater level, the soil forms a conical erosion zone under coupled seepage-gravity action, while above the water level, collapse occurs primarily through vertical shear failure, exhibiting characteristics typical of dry sand collapse.

Due to objective constraints such as the lengthy duration and high economic cost of physical model experiments, this study only completed indoor simulation tests on homogeneous sandy soil layers. However, in engineering practice, underground geotechnical bodies generally exhibit complex geological characteristics such as blurred stratigraphic interfaces, organic inclusions, and strong heterogeneity in material composition, whose mechanical response mechanisms differ significantly from those of homogeneous strata. Subsequent research urgently needs to expand physical modeling to a variety of complex stratigraphic conditions, with a focus on typical engineering scenarios involving weak interlayers, gravel-clay mixed deposits, and highly heterogeneous strata.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the need for follow-up studies but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, M., Ren, H., Wang, F. & Zhang, D. Influence of clay content on the scour resistance of roadbeds along river highways. Rock. Soil. Mech. 45, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2023.0882 (2024).

Zhang, S., Bao, T. & Liu, C. Model tests and numerical modeling of the failure behavior of composite strata caused by tunneling under pipeline leakage conditions. Eng. Fail. Anal. 149, 107287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2023.107287 (2023).

Wang, X. W. & Xu, Y. S. Investigation on the phenomena and influence factors of urban ground collapse in China. State Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering, School of Naval Architecture, Ocean, and Civil Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 800 Dong Chuan Road, Minhang District, 200240, Shanghai, China;Shanghai Key Laboratory for Digital Main 113, 1–33, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05304-z

Carbognin, L., Teatini, P. & Tosi, L. Eustacy and land subsidence in the Venice lagoon at the beginning ofthe new millennium. J. Mar. Syst. 51, 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2004.05.021 (2004).

Aydin, N. Y., Duzgun, H. S., Heinimann, H. R., Wenzel, F. & Gnyawali, K. R. Framework for improving the resilience and recovery of transportation networks under geohazard risks. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 31, 832–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.07.022 (2018).

Wang, K. et al. Causes, Risk Analysis, and Countermeasures of Urban Road Collapse in China from 2019 to 2020. Ph.D. Engineer, School of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Xi’an Univ. of Technology, Xi’an, Shaanxi Province 710048, China; Civil Engineer, State Key Laboratory of Rail Transit Engineering Informati Vol.36, 1–12, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)cf.1943-5509.0001765

Yuan, X., Yan, Y., Li, X., Wang, T. & Ji, J. Discrete element simulation of ground collapse induced by buried sewage pipeline breakage and soil leakage. Eng. Fail. Anal. 167, 108910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108910 (2025).

Lo, W., Purnomo, S. N., Dewanto, B. G. & Sarah, D. Sumiyanto. Integration of numerical models and InSAR techniques to assess land subsidence due to excessive groundwater abstraction in the coastal and lowland regions of Semarang City. Water 14, 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14020201 (2022).

Zoueshtiagh, F. & Merlen, A. Effect of a vertically flowing water jet underneath a granular bed. Phys. Rev. E. 75, 056313. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.75.056313 (2007).

Tang, Y., Zhu, D. Z., Chan, D. H. & Zhang, S. Physical and analytical modeling of soil loss caused by a defective sewer pipe with different defect locations. Acta Geotech. 18, 2639–2659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-022-01747-7 (2023).

Shi, X. et al. Study on the rules of ground settlement and pipeline deformation considering the combined effects of pipeline damage leakage and shield tunneling construction. Transp. Geotechnics. 49, 101367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2024.101367 (2024).

Guo, S. et al. Experimental study on the soil erosion through a defective pipe under the Cyclic infiltration-exfiltration flow. Transp. Geotechnics. 42, 101085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2023.101085 (2023).

Dastpak, P., Sousa, R. L. & Dias, D. Soil erosion due to defective pipes: A hidden hazard beneath our feet. Sustainability 15, 8931. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118931 (2023).

Yuan, S., Feng, D., Zhang, S. & Lin, R. Support pressure assessment of tunnels in the vicinity of leaking pipeline using unified upper bound limit analysis. Comput. Geotech. 144, 104662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.104662 (2022).

Cui, X. L., Tao, G. L. & Li, J. & Iop. in 2nd International Workshop on Renewable Energy and Development (IWRED). (2018).

Zhang, D., Zhang, X. & Du, W. DEM-FEM based numerical analysis on mechanical responses of sandy soil and pipeline to seepage erosion. Eng. Geol. 310, 106868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106868 (2022).

Ibrahim, A. & Meguid, M. A. CFD-DEM simulation of sand erosion into defective gravity pipes under constant groundwater table. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 131, 104823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104823 (2023).

Long, Y. Y. & Tan, Y. Soil arching due to leaking of tunnel buried in water-rich sand. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 95, 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2019.103158 (2020).

Wang, Z. Y., Tan, Y. & Long Y. Y. in 5th GeoShanghai International Conference. (2024).

Shiau, J., Chudal, B., Mahalingasivam, K. & Keawsawasvong, S. Pipeline burst-related ground stability in blowout condition. Transp. Geotechnics. 29, 100587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2021.100587 (2021).

Indraratna, B., Minh, N., Thanh Trung, P., Huang, J. & N. & Simulating subgrade soil fluidization using LBM-DEM coupling. Int. J. Geomech. 21, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gm.1943-5622.0001997 (2021).

He, M., Zhou, Z., Qin, L., Yong, H. & Chen, C. MFL detection of adjacent pipeline defects: a finite element simulation of signal characteristics. Insight 66, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1784/insi.2024.66.6.353 (2024).

Sato, M. & Kuwano, R. Influence of location of subsurface structures on development of underground cavities induced by internal erosion. Soils Found. 55, 829–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2015.06.014 (2015).

Ke, L. & Takahashi, A. Triaxial erosion test for evaluation of mechanical consequences of internal erosion. Geotech. Test. J. 37, 19. https://doi.org/10.1520/gtj20130049 (2014).

Mukunoki, T., Kumano, N. & Otani, J. Image analysis of soil failure on defective underground pipe due to cyclic water supply and drainage using X-ray CT. X-Earth Center, Graduate School of Science and Technology, Kumamoto University, 1-39-2 Kurokami, Kumamoto, 860–8555, Japan Toshifumi Mukunoki, Naoko Kumano & Jun Otani Vol. 6, 85–100, (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-012-0159-5

Alsaydalani, M. O. A. & Clayton, C. R. I. Internal fluidization in granular soils. J. Geotech. GeoEnviron. Eng. 140, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)gt.1943-5606.0001039 (2014).

Liu, J. C., Wang, Z. Y., Tan, Y. & Cao, Y. C. Failure evolution and mechanism of ground collapse due to exfiltration of shallowly buried water pipeline. Eng. Fail. Anal. 162, 108390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108390 (2024).

Tan, F. et al. Model test analysis of subsurface cavity and ground collapse due to broken pipe leakage. Appl. Sciences-Basel. 12, 13017. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122413017 (2022).

Indiketiya, S., Jegatheesan, P. & Rajeev, P. Evaluation of defective sewer pipe-induced internal erosion and associated ground deformation using laboratory model test. Can. Geotech. J. 54, 1184–1195. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2016-0558 (2017).

Guo, S. & Zhu, D. Z. Soil and groundwater erosion rates into a sewer pipe crack. J. Hydraul. Eng. 143, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)hy.1943-7900.0001306 (2017).

Wood, D. M., Maeda, K. & Nukudani, E. Modelling mechanical consequences of erosion. Geotechnique 60, 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.2010.60.6.447 (2010).

Wang, Y., Shi, G., Tian, X., Li, C. & Cheng, H. Experimental study on City road collapse under vibrating load. Shock Vib. 2020, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6074658 (2020).

Guo, J. et al. Model experimental study on the mechanism of collapse induced by leakage of underground pipeline. Sci. Rep. 14, 17717. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68824-7 (2024).

Huang, M., Li, Y., Shi, Z. & Lu, X. Face stability analysis of shallow shield tunneling in layered ground under seepage flow. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 119, 104201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104201 (2022).

Ding, L. & Liu, Y. Study on overlying strata motion rule of shortwall mining face of shallow seam with simulation experiment. J. Min. Sci. 55, 775–782. https://doi.org/10.1134/s1062739119056148 (2019).

Dai, Z., Peng, L. & Qin, S. Experimental and numerical investigation on the mechanism of ground collapse induced by underground drainage pipe leakage. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-023-11344-w (2024).

Tang, Y., Zhu, D. Z. & Chan, D. H. Experimental study on submerged sand erosion through a slot on a defective pipe. J. Hydraul. Eng. 143, 04017026. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)hy.1943-7900.0001326 (2017).

Ren, J., Liu, Y., Yu, P., Zhang, Y. & Li, D. The influence of fines content on ground collapse due to internal erosion of sand-fines mixtures around defective pipes. Eng. Fail. Anal. 165, 108810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108810 (2024).

Wang, M., Li, S., Zhou, H., Peng, K. & Yuan, C. Visualization investigation of the large deformation and instability failure of shield tunnel using transparent soil models. Eng. Fail. Anal. 166, 108861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108861 (2024).

Liu, C., Zhang, S., Zhang, D., Zhang, K. & Wang, Z. Model tests on progressive collapse mechanism of a shallow subway tunnel in soft upper and hard lower composite strata. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 131, 104824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104824 (2023).

Bantu, A. B., Bracamontes, L. A. I., Gamboa, G. V. & Reyes, C. C. Modeling multiphasic flow and bubbling nonfluidized beds in water-filled sediment. Exp. Comput. Multiph. Flow. 7, 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42757-024-0192-3 (2025).

Roccon, A., Soligo, G. & Soldati, A. FLOW36: A spectral solver for phase-field based multiphase turbulence simulations on heterogeneous computing architectures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 313, 109640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2025.109640 (2025).

Guo, J. et al. Study on urban ground collapse induced by defective pipelines based on physical model experiments and numerical simulation. Sci. Rep. 15, 6085. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90146-5 (2025).

Funding

This study was supported by Jiangsu Provincial Key R&D Programme (Social Development) with the research number BE2022820 and National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFE0102600).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

**Qize Zhu** : Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing − original draft, Formal analysis, Validation. **Yu Shen** :Conception, Methodology, Analysis. **Chichen Han** : Analysis, Methodology. **Guanzheng Wu** : Conception, Analysis. **Yunfeng Li** : Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing − review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Q., Shen, Y., Han, C. et al. Study on stress response and collapse mechanism induced by shallow-buried defective pipelines in river alluvial plains. Sci Rep 16, 1769 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30500-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30500-9