Abstract

The integration of 3D technologies into education opens up new opportunities for the study and preservation of cultural artifacts, particularly in the context of studying ceramics. This study aims to assess the impact of using laser scanning and 3D printing technologies on student satisfaction with the educational process. The study had a quasi-experimental design with two groups. The theoretical part of the taught course “Ceramics of China and Southeast Asia” was the same for both groups. The Intervention group (n = 114) used 3D scanning and printing in practical classes, while the Control group (n = 114) studied using traditional methods. The course lasted 15 weeks. At the end of the course, students in both groups completed a questionnaire on the scales Tutor Guidance & Support, Satisfaction, Content & Experience, Collaboration & Activities. The results of the questionnaire of students in both groups were compared using an independent t-test. The influence of individual student characteristics (gender, age, previous experience) was determined using one-way ANOVA. The Intervention group showed significantly higher scores on Satisfaction, Content & Experience, and Collaboration & Activities than the Control group. Gender and previous experience influenced the course’s perception, while the students’ age was not a significant factor. The obtained results are important for the development of 3D approaches to learning in the field of cultural heritage and archaeology, as well as for the creation of more interactive and effective educational programs that use modern technologies for the preservation and study of cultural artifacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contemporary three-dimensional technologies, such as 3D printing and 3D scanning, are opening new horizons for education and the preservation of cultural heritage1,2 Specifically, 3D scanning technologies, including the Kinect, and 3D modelling, enable the accurate capture of the geometry of real-world objects and their representation in digital form3. The use of automated scanning and modelling approaches has made 3D scanning technology accessible even to unskilled users3.

This shift is transforming the approach to learning, making it more hands-on and facilitating a deeper understanding of conceptual knowledge.

Structured and laser 3D scanners utilize the projection of light patterns or laser lines to collect data with high precision, ensuring the detailed representation of even the most complex objects4. These technologies are widely employed across various industries, from manufacturing to healthcare, and in creating visual effects for films and video games5,6,7.

In addition, 3D scanning is increasingly used in the preservation of cultural heritage and artistic projects. This technology allows for the digital conservation of artifacts, the creation of reproducible 3D-printed copies, and the sharing of cultural materials within academic circles8,9,10. Artists and art historians incorporate real objects into their works, while museums employ scanning to preserve valuable collections4.

Despite the successful application of 3D scanning and printing across various fields, including archaeology and art, there is a limited amount of research that specifically analyzes their use for education and the study of cultural artifacts. Most existing studies focus on the technological aspects of these technologies,11,12 rather than how these tools can contribute to a deeper understanding and preservation of cultural heritage within educational programs.

The preservation of cultural heritage through digital technologies is an important and well-explored topic among researchers4,13 However, regarding 3D printing and 3D scanning, there is a noticeable gap in knowledge concerning how these three-dimensional technologies can be utilized in education to enhance the understanding and preservation of ceramic artifacts. This study aims to address this gap by comparing the effectiveness of traditional teaching methods with modern technologies such as 3D scanning and 3D printing. The focus of the research is on Chinese and South Asian ceramic artifacts, due to their high cultural, historical, and artistic value, which makes them significant objects for study and preservation14. These artifacts represent the rich traditions of regions known for their complex manufacturing techniques and symbolic meanings, offering unique opportunities for the use of 3D technologies in the educational process. The objective of this study is to assess the impact of using Laser Scanning and 3D Printing technologies on student satisfaction with the learning process.

Advantages of laser scanning and 3D printing for the study and preservation of artifacts: Theoretical justification

Traditional research methods, such as visual inspection or drawings, are limited in their ability to reproduce the details of artifacts15. In contrast, Laser Scanning provides high accuracy in the digital reproduction of objects, including fine details, surface defects, and textures11. Furthermore, digitization through laser scanning is a safe method that allows for the study of fragile artifacts without physical contact, unlike manual measurements or manipulations16.

3D models enable the creation of interactive representations, which students can rotate, scale, and explore from various angles17. Lost parts of artifacts can also be reconstructed,18 which is not possible with traditional approaches. This aligns with constructivist learning theory,19 which emphasizes active interaction with learning materials as key to better knowledge acquisition. A comparative analysis of the key characteristics of traditional learning methods and innovative technologies such as Laser Scanning and 3D Printing is presented below (Table 1).

Research indicates that the use of digital technologies, such as virtual reality or 3D models, significantly enhances the learning experience20. This is achieved through (1) increased student engagement via interactivity;21 and (2) enhanced spatial understanding of complex objects and their structures22. According to the cognitive theory of multimedia learning,23 combining visual and interactive methods facilitates better comprehension of complex information.

Thus, the application of Laser Scanning and 3D Printing in the study and preservation of Southeast Asian ceramic artifacts is justified by their technological efficiency, safety for the original artifacts, and the ability to create accessible and interactive learning materials. These approaches not only improve the learning process but also ensure the long-term preservation of cultural heritage in digital format, making them promising and significant for contemporary education and archaeology. In addition to the technical advantages, it is important to consider how the integration of these technologies into educational programs affects student satisfaction.

The relationship between instructional design and student satisfaction

Student satisfaction research in digital versus traditional learning is an important area of educational science, as it allows for the evaluation of the effectiveness of selected teaching strategies and their impact on academic outcomes24,25 Satisfaction assessment not only provides feedback for instructors but also serves as a tool for improving curricula26.

The design of the learning experience plays a crucial role in shaping satisfaction. According to Park and Kim,27 well-designed, thoughtfully organized content engages students and contributes to their satisfaction. As noted by Kwangmuang et al.,28 the integration of innovative approaches into the structure of learning materials can significantly enhance the student learning experience. 3D virtual learning environments can also influence satisfaction by improving the learning experience29,30.

Virtual simulations and three-dimensional imagery, in the context of cultural heritage study, increase student engagement and satisfaction through immersion31. However, the role of the instructor remains critical. Their competence in working with three-dimensional environments, their support, and their ability to collaborate flexibly with students are considered key factors for successful learning and student satisfaction32. Researchers also highlight that the quality and realism of 3D images significantly influence student satisfaction33. Realistic and engaging 3D images improve the learning experience33.

A number of studies34,35,36 emphasize the importance of a systematic approach to assessing satisfaction, which includes both the quality of interaction between instructors and students and the accessibility of learning materials and technological resources. In this context, standardized tools, such as the Course Experience Questionnaire, help measure key satisfaction indicators, including the quality of teaching, student support, and personal development37. These questionnaires are widely used in research37,38,39 as they allow for data systematization and the identification of relationships between the learning environment and student satisfaction.

Previous studies also emphasize the need to consider individual student characteristics. For example, researchers Pal and Patra40 and Tsang et al.41 highlight that demographic data, prior educational experience, and socio-economic factors can significantly influence students’ perceptions of the learning process in digital education.

Thus, digital technologies, such as Laser Scanning and 3D Printing, open new opportunities for engaging students in deeper study of cultural artifacts, allowing for interactive interaction with learning materials. This approach not only has the potential to make the learning process more engaging but also contributes to enhancing student satisfaction. In light of this, the study focuses on the following research questions (RQ): Does the use of 3D technologies influence student satisfaction with the course compared to traditional teaching methods (RQ1), and what individual student characteristics (gender, prior experience, age) affect satisfaction with a 3D technology-based course (RQ2)?

Methodology

The study was conducted using a quasi-experimental design with two groups: control and experimental. The theoretical part of the training was the same for both groups. The practical and laboratory classes of the Control group were conducted using traditional approaches, while the Intervention group used laser scanning and 3D printing during laboratory and practical classes.

Participants

The study involved second-year students enrolled in the “Archaeology” and “Art” programs at Guilin University of Technology, China. A total of 228 students participated in the course, randomly assigned to the Control group (n = 114) and the Intervention group (n = 114). The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 26 years. The Intervention group consisted of 56 females and 58 males, while the Control group comprised 57 females and 57 males.

Procedure

The course “Ceramics of China and Southeast Asia” lasted 15 weeks and consisted of lectures, discussions, and practical sessions focused on studying traditional methods of ceramic artifact preservation, as well as the integration of cutting-edge technologies. Both groups had two sessions per week, each lasting 1.5 h (one lecture and one laboratory/practical session). The same instructor, with 18 years of teaching experience, led the course.

The course was divided into 8 modules. Students were introduced to the fundamental ceramic manufacturing technologies and explored the development of ceramics in China and Southeast Asia from the Neolithic period to the present. A detailed course outline is presented in Fig. 1.

Both groups participated in practical and laboratory work, though the format varied depending on the methods used (Table 2). The Control group followed the traditional approach to practical and laboratory work, focusing on 2D analysis. The Intervention group utilized the latest three-dimensional technologies, including 3D scanning and 3D printing, to create accurate digital representations of Chinese and Southeast Asian ceramic specimens.

Students in the Control group were actively involved in modeling and reproducing traditional ceramic artifacts as objects of study, which elicited a much greater attention to the smallest details and characteristics of the objects. They also had the opportunity to participate in the process of recreating not only the finished product but also elements of the technical processes of ceramic production at various stages, which enhanced their understanding of the technology. Following the laboratory sessions, students in both groups were required to present presentations based on their acquired knowledge and their own projects, using 2D or 3D models to recreate specific artifacts, their history, the technology of their creation, and the cultural, historical, and artistic context. Following each module, students presented their instructors with a final project reflecting all the knowledge gained during the module and their reflection on their personal experiences.

During the course, instructors not only covered the course material but also provided feedback to students in class, while preparing their personal projects, and before module submissions. In the Intervention group, instructors, along with university engineering specialists, explained the use of 3D scanning and printing technologies to students and assisted them in creating their own models in class or individually at their own request, using a separate schedule for their own models and presentations. Students in the Control group received similar support with processing and creating 2D images.

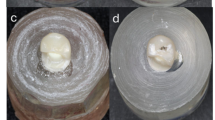

The study utilized the Artec Space Spider 3D scanner (Fig. 2a). It has an accuracy of up to 0.05 mm and a resolution of 0.1 mm, which is important for ceramic artifacts with fine details and intricate decoration. It is also fast and allows for the creation of 3D models of medium-sized objects in a short amount of time. Additionally, this device is user-friendly and does not require complex calibration.

Used equipment: a - Artec Space Spider, b - Formlabs Form 3+.

The study also used the Formlabs Form 3 + 3D printer (Fig. 2b). It has a print accuracy of up to 0.025 mm and a layer resolution of 25 microns, allowing for the reproduction of the smallest ornaments and texture elements of artifacts. It operates on the principle of stereolithography (SLA): using liquid resin, which ensures high detail and a smooth surface. It also features an intuitive interface and an automated model preparation process. The working chamber dimensions are 145 × 145 × 185 mm. The printer supports CAD files and models created with 3D scanners.

Scales

Upon completion of the intervention after 15 weeks of classes, at the beginning of the 16th week from the start of classes on the course, students completed a survey. A standardized questionnaire was used to measure student satisfaction, adapted from instruments such as the Course Experience Questionnaire42 and other similar methodologies43,44 The questionnaire consisted of 20 items assessing various aspects of the learning experience, including Tutor Guidance & Support (7 items), Satisfaction (6 items), Content & Experience (4 items), and Collaboration & Activities (3 items). Each item was rated on a 0 to 5 Likert scale, where 0 = strongly disagree, 1 = mostly disagree, 2 = slightly disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = mostly agree, and 5 = strongly agree. For example, for the question “Overall, I am satisfied with the learning materials provided,” a score of 0 indicated that the materials were completely unsuitable, unclear, or absent, while a score of 5 indicated that the materials were perfectly prepared and fully met expectations and needs.

Additionally, on the same day as described above survey students were asked to report their age, gender, and prior experience with the use of three-dimensional imagery for educational purposes. This approach enabled a comparison of the effectiveness of the teaching design used in both groups and helped identify the key factors contributing to increased student satisfaction.

The graphical sequence of the methodological stages of the study is presented in Fig. 3.

Statistical data analysis

The data were tested for normality of distribution using graphical methods (histograms). Levene’s test indicated homogeneity of variances. An independent t-test (Student’s t-test) was used to determine differences in satisfaction scores between the control and experimental groups. The effect size was evaluated using Cohen’s d, where small effect = 0.2, medium effect = 0.5, and large effect = 0.8. A one-way ANOVA was employed to assess the impact of individual student characteristics, such as demographic data (age, gender) and prior educational experience. For the one-way ANOVA, the effect size was determined using partial eta squared (η2): small (η2 = 0.01–0.05), moderate (η2 = 0.06–0.09), and large (η2 at least 0.1).

Ethical issues

Participation in the study was voluntary. All participants were informed about the purpose and course of the study. Students participated voluntarily in the study and were informed before it began that they could withdraw from participation at any time. No personal information was stored or collected. The study received approval from the Guilin University of Technology Ethics Committee.

Results

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis are presented in Table 3. The second column of the table shows the factor loadings, the third column displays the Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and the fourth column presents the Composite Reliability (CR).

For Tutor Guidance & Support, the factor loadings range from 0.73 to 0.89, with AVE = 0.75 and CR = 0.91. For Satisfaction, the factor loadings range from 0.76 to 0.89, with AVE = 0.76 and CR = 0.93. For Content & Experience, the factor loadings range from 0.78 to 0.92, with AVE = 0.83 and CR = 0.94. Finally, for Collaboration & Activities, the factor loadings range from 0.81 to 0.86, with AVE = 0.75 and CR = 0.89.

Factor loadings greater than 0.70 are considered high and acceptable for confirming that each indicator is well explained by the corresponding factor45. All factor loadings fall within the range of 0.73–0.92. This indicates that each item is strongly associated with the corresponding latent variable and adequately reflects it. AVE values greater than 0.50 indicate high convergent validity, meaning that the indicators accurately measure the latent variable they are intended to represent45. CR values greater than 0.70 indicate high reliability45. In this case, CR values range from 0.89 to 0.94, confirming that the measurement instrument is stable and reliable.

Comparison of student satisfaction levels when using traditional teaching methods and laser scanning and 3D printing technologies

Descriptive statistics (M, SD) and the results of independent-sample t-tests between course evaluations by students in the Intervention group and the Control group are presented in Table 4. For the Tutor Guidance & Support scale, the Intervention group (M = 3.51, SD = 0.91) and the Control group did not show statistically significant differences (t = − 0.532, p = 0.107). Thus, the use of 3D technologies did not have a significant impact on ratings of tutor support and guidance. It appears that the instructor was equally effective in adapting to both learning formats, with the teaching methodology being the key factor rather than the technology.

For Satisfaction, the Intervention group (M = 3.80, SD = 0.83) rated significantly higher than the Control group (M = 3.42, SD = 0.81) (t = 3.498, p = 0.015). Participants in the Intervention group demonstrated a higher level of satisfaction, likely due to the interactivity and modernity of the 3D technologies. These methods appear to have increased interest in the learning process and contributed to deeper student engagement.

For the Content & Experience scale, the Intervention group (M = 3.94, SD = 0.77) significantly outperformed the Control group (M = 3.46, SD = 0.69): t = 4.957, p = 0.001. The use of three-dimensional technologies allowed students in the Intervention group to interact more effectively with the material, providing a richer learning experience. The ability to perform 3D analysis and experimental reproduction facilitated a more thorough understanding of ceramic specimens.

For the Collaboration & Activities scale, the Intervention group (M = 3.89, SD = 0.74) also rated the course significantly higher than the Control group (M = 3.56, SD = 0.76): t = 3.322, p = 0.001. The application of modern technologies fostered better teamwork, as students were able to work together on digital models, discuss reconstructions, and analyze interregional influences. This may also be explained by increased engagement due to interactivity.

The influence of individual student characteristics on their satisfaction with the course

A one-way ANOVA was used to identify the factors influencing student satisfaction with the course “Ceramics of China and Southeast Asia.” A relationship was observed between participant satisfaction and gender (F = 11.24, p = 0.001), with a medium effect size (η2 = 0.08). The mean scores indicated that female students were generally more satisfied with the course than male students. Additionally, the influence of prior experience on satisfaction with the project was observed (F = 12.21, p = 0.000), with a medium effect size (η2 = 0.09). Participants with no prior experience in 3D visualization rated the project higher than those who had previously worked with 3D images. No effect of participants’ age on course satisfaction was found (F = 1.77, p = 0.115). The lack of a statistically significant effect suggests that participants from different age groups rated the course equally equally, indicating its content’s universality.

Discussion

The use of advanced three-dimensional technologies (3D scanning, 3D printing) in the Intervention group significantly improved satisfaction, learning experience, and collaboration outcomes (RQ1). The obtained data align well with the conclusions of previous studies,17,22 which suggest that 3D models enable students to interact with learning material in a way that enhances their engagement and spatial understanding of complex objects. Additionally, the current results support the constructivist learning theory,19 which emphasizes the importance of active interaction with learning materials to improve knowledge acquisition. The data indicate a higher level of satisfaction with the course that incorporated 3D technologies compared to traditional methods. This is consistent with studies by Lackovic et al.31 and Violante et al.21 which demonstrate that interactive and visual elements significantly enhance the learning experience and increase student motivation.

Thus, the use of 3D scanning and 3D printing in the Intervention group facilitated a deeper understanding of the material through the analysis of realistic digital models and the ability to conduct experimental reproductions; fostered interactivity and student engagement in the learning process; and expanded competencies in working with modern technologies. The Control group, which employed the traditional approach (text analysis, diagrams, and photographs), was more limited in terms of practical interaction with the material, which impacted overall satisfaction and engagement. This highlights the importance of integrating innovative methods into practical and laboratory activities to enhance the effectiveness of learning when studying cultural heritage.

Individual characteristics such as gender and prior experience influence course perception, while students’ age is not a significant factor (RQ2). This aligns with the findings of Pal and Patra,40 Tsang et al.41 and who emphasize that demographic and socio-economic factors have a significant impact on the perception of digital learning environments. The results regarding gender and prior experience could serve as a basis for further course improvements. For instance, it may be beneficial to consider the specific interests of male students and more experienced participants to enhance their satisfaction. The lack of an age effect is viewed as a positive aspect, as the course is likely designed to be accessible and engaging for audiences of various ages.

The application of 3D technologies enables global access to digitized artifacts, which corresponds with the observations of Qureshi et al.20 regarding the enhancement of the learning experience through resource availability. As noted by Pintore et al.,18 the ability to reconstruct lost parts of artifacts makes these technologies particularly valuable for cultural heritage preservation.

Thus, the integration of 3D technologies can transform the learning process, making it more effective, flexible, and appealing to students of varying levels of preparation. Realistic 3D models contribute to a better understanding of the material compared to traditional drawings or photographs. This is facilitated through visualization and the ability to visually analyze the intricate details of artifacts through their accurate reproduction, as also observed in this study. Using 3D models and simulations, training can be conducted to model real research conditions, preparing students for practical work. This is an important conclusion not only for cultural heritage education but also for engineering and natural sciences, where objects have complex structures and compositions.

It’s important to emphasize that the proposed intervention demonstrated that the most crucial issue for replicability and scalability—technology availability and faculty training—is resolved more easily than expected. Given the cost of a 3D printer, technology at the required level is readily available to virtually any university, and training technical support specialists in departments takes just a few lessons. This is due to the rapid reduction in cost, proliferation, and attractiveness of these technologies. Young undergraduates, graduate students, and departmental lab assistants are interested and motivated to learn 3D modeling and printing skills, and many universities already have such technologies. Some researchers have already indicated that 3D printing technologies will rapidly penetrate university practice for the reasons described here29,31.

This study has potential limitations. Since the survey relied on self-reporting by participants, it imposes certain limitations related to the potential social desirability of the responses and potential response bias (in the form of social desirability bias or response bias). These limitations should be mitigated in future studies using objective measurements of participants’ knowledge and cognitive abilities during classes and through triangulation with validated similar measures.

The relatively small sample size may reduce the generalizability of the results to a broader student population. The use of a survey to measure satisfaction may have led to socially desirable responses or biased evaluations. The short duration of the study may not have fully reflected the impact of the technologies on student learning. Long-term monitoring is needed to assess the sustainability of the results. Students may have shown increased interest in the learning process due to the novelty of the technologies, which could have temporarily influenced their satisfaction. This effect may decrease as the use of 3D technologies in education becomes more widespread. The cost and availability of modern equipment may limit the scalability of the study.

Conclusions

The use of 3D technologies, such as laser scanning and 3D printing, has been shown to be an effective tool for increasing student satisfaction with the learning process. Students who worked with these technologies rated the course “Ceramics of China and Southeast Asia” significantly higher in terms of satisfaction, learning content, and collaboration compared to the group that studied using traditional methods. Individual characteristics of students, in particular, gender and previous experience, had an impact on the perception of the course, which confirms the need for individualization of educational approaches in the context of using the latest technologies. The use of 3D technologies in teaching can be an important tool for teachers who seek to provide more interactive and visual learning in fields such as archaeology, art history, and cultural heritage conservation. There is a need to develop curricula that include the use of new technologies to improve understanding of complex topics such as history and art, particularly in the study of cultural artifacts. Since individual student characteristics can affect learning effectiveness, it is important to implement differentiated approaches to the use of technology in the educational process, adapting them to different categories of students.

Future research should focus on examining the impact of different types of 3D technologies (e.g., various types of scanners or 3D printers) on the quality of learning and student satisfaction in different educational contexts. Additionally, future studies could explore the long-term effects of using 3D technologies on students’ knowledge and their ability to engage in self-directed learning. Comparative studies investigating the impact of 3D technologies on students with diverse academic backgrounds and experiences would also be promising, as they could help develop more personalized educational strategies.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Harris, A., Cremaschi, A., Lim, T. S., De Iorio, M. & Kwa, C. G. From past to future: digital methods towards artefact analysis. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 39, 1026–1042. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqae057 (2024).

Olalere, O. Sustainable archaeology: The use of low-cost and higher-cost technology for 3D documentation of archaeological objects from the Zulu Kingdom period, South Africa. Thesis, University of Manitoba (2023).

O’Hare, D., Hurst, W., Tully, D. & Rhalibi, A. E. A study into autonomous scanning for 3D model construction. In E-Learning and Games: 11th International Conference, Edutainment Bournemouth, UK, June 26–28, 2017, Revised Selected Papers 11 (ed. Tian, F.) 182–190 (Springer International Publishing, 2017). (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65849-0_19

Haleem, A. et al. Exploring the potential of 3D scanning in industry 4.0: an overview. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 3, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcce.2022.08.003 (2022).

Confalone, G. C., Smits, J. & Kinnare, T. 3D Scanning for Advanced manufacturing, design, and Construction (Wiley, 2023).

Ling, X. Research on Building measurement accuracy verification based on terrestrial 3D laser scanner. IOP Conf. Ser. : Earth Environ. Sci. 632, 052086. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/632/5/052086 (2021).

Sepasgozar, S. M., Shi, A., Yang, L., Shirowzhan, S. & Edwards, D. J. Additive manufacturing applications for industry 4.0: A systematic critical review. Buildings 10, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings10120231 (2020).

Kovar, J. et al. Virtual reality in context of Industry 4.0 proposed projects at Brno University of Technology. In 17th International Conference on Mechatronics-Mechatronika (ME) (ed. Maga, D.) 1–7 (IEEE, 2016). (ed. Maga, D.) 1–7 (IEEE, 2016). (2016). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/7827785

Wang, J., Tao, B., Gong, Z., Yu, S. & Yin, Z. A mobile robotic measurement system for large-scale complex components based on optical scanning and visual tracking. Robot Comput. Integr. Manuf. 67, 102010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2020.102010 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Recovery of defocused 3D data for focusing-optics-based amplitude-modulated continuous-wave laser scanner. In SPIE Future Sensing Technologies (eds. Kimata, M. & Valenta, C. R.) Vol. 11197, 57–60 (SPIE, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2542489

Kantaros, A., Ganetsos, T. & Petrescu, F. I. T. Three-dimensional printing and 3D scanning: emerging technologies exhibiting high potential in the field of cultural heritage. Appl. Sci. 13, 4777. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13084777 (2023).

Malik, U., Tissen, L. N. & Vermeeren, A. P. 3D reproductions of cultural heritage artifacts: evaluation of significance and experience. Stud. Digit. Herit. 5, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.14434/sdh.v5i1.32323 (2021).

Wang, Y., Wu, T. & Huang, G. State-of-the-art research progress and challenge of the printing techniques, potential applications for advanced ceramic materials 3D printing. Mater. Today Commun. 40, 110001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.110001 (2024).

Sirisathitkul, C. Advancements in characterization of ancient potteries from Southeast asia: A review of analytical techniques. Makara J. Sci. 28, 5. https://doi.org/10.7454/mss.v28i1.2127 (2024).

Hou, Y., Kenderdine, S., Picca, D., Egloff, M. & Adamou, A. Digitizing intangible cultural heritage embodied: state of the Art. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 15, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1145/3494837 (2022).

Cieslik, E. 3D Digitization in Cultural Heritage Institutions Guidebook (University of Maryland, 2020).

Teplá, M., Teplý, P. & Šmejkal, P. Influence of 3D models and animations on students in natural subjects. Int. J. STEM Educ. 9, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-022-00382-8 (2022).

Pintore, G. et al. State-of-the-art in automatic 3D reconstruction of structured indoor environments. Comput. Graph Forum. 39, 667–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.14021 (2020).

Narayan, R., Rodriguez, C., Araujo, J., Shaqlaih, A. & Moss, G. Constructivism—Constructivist learning theory. In The Handbook of Educational Theories (eds. Irby, B. J., Brown, G., Lara-Alecio, R. & Jackson, S.) 169–183IAP Information Age Publishing, (2013). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2013-11995-015

Qureshi, M. I., Khan, N., Raza, H., Imran, A. & Ismail, F. Digital technologies in education 4.0. Does it enhance the effectiveness of learning? Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 15, 31–47. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v15i04.20291 (2021).

Violante, M. G., Vezzetti, E. & Piazzolla, P. Interactive virtual technologies in engineering education: why not 360° videos? Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 13, 729–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12008-019-00553-y (2019).

Molina-Carmona, R., Pertegal-Felices, M. L., Jimeno-Morenilla, A. & Mora-Mora, H. Virtual reality learning activities for multimedia students to enhance Spatial ability. Sustainability 10, 1074. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041074 (2018).

Mayer, R. E. The past, present, and future of the cognitive theory of multimedia learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 36, 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09842-1 (2024).

Bobe, B. J. & Cooper, B. J. Accounting students’ perceptions of effective teaching and approaches to learning: impact on overall student satisfaction. Acc. Finance. 60, 2099–2143. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12364 (2020).

Låg, T. & Sæle, R. G. Does the flipped classroom improve student learning and satisfaction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. AERA Open. 5, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419870489 (2019).

Pandita, A. & Kiran, R. The technology interface and student engagement are significant stimuli in sustainable student satisfaction. Sustainability 15, 7923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107923 (2023).

Park, S. Y. & Kim, J. H. Instructional design and educational satisfaction for virtual environment simulation in undergraduate nursing education: the mediating effect of learning immersion. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 673. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03728-6 (2022).

Kwangmuang, P., Jarutkamolpong, S., Sangboonraung, W. & Daungtod, S. The development of learning innovation to enhance higher-order thinking skills for students in Thailand junior high schools. Heliyon 7, e07309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07309 (2021).

Alhonkoski, M., Salminen, L., Pakarinen, A. & Veermans, M. 3D technology to support teaching and learning in health care education–A scoping review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 105, 101699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101699 (2021).

Saleeb, N. & Dafoulas, G. Effects of virtual world environments in student satisfaction: An examination of the role of architecture in 3D education. In Governance, Communication, and Innovation in a Knowledge Intensive Society (ed. Siqueira, S. W. M.) 203–221IGI Global, (2013). https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-4157-0.ch017

Lackovic, N., Crook, C., Cobb, S., Shalloe, S. & D’Cruz, M. Imagining technology-enhanced learning with heritage artefacts: Teacher-perceived potential of 2D and 3D heritage site visualisations. Educ. Res. 57, 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1058098 (2015).

Zhang, X., Huang, R. & Chen, H. An empirical study of the critical factors influencing learner satisfaction and effectiveness: A 3D CAD system’s perspective. J. Softw. 8, 2503–2510. https://doi.org/10.4304/jsw.8.10.2503-2510 (2013).

Silén, C. et al. Three-dimensional visualisation of authentic cases in anatomy learning–An educational design study. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 477. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03539-9 (2022).

Dahleez, K. A., El-Saleh, A. A., Alawi, A., Abdel Fattah, F. A. M. & A. M. & Student learning outcomes and online engagement in time of crisis: the role of e-learning system usability and teacher behavior. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 38, 473–492. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJILT-04-2021-0057 (2021).

Rajabalee, Y. B. & Santally, M. I. Learner satisfaction, engagement and performances in an online module: implications for institutional e-learning policy. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 2623–2656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10375-1 (2021).

Wang, X., Hassa, A. B., Pyn, H. S. & Ye, H. Exploring the influence of teacher-student interaction strength, interaction time, interaction distance and interaction content on international student satisfaction with online courses. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 21, 380–396. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.21.2.21 (2022).

Li, N., Marsh, V. & Rienties, B. Modelling and managing learner satisfaction: use of learner feedback to enhance blended and online learning experience. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 14, 216–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12096 (2016).

Ali, H. & Mohd Dodeen, H. An adaptation of the course experience questionnaire to the Arab learning context. Assess. Eval High. Educ. 46, 1104–1114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1841733 (2021).

Rehman, M. A., Woyo, E., Akahome, J. E. & Sohail, M. D. The influence of course experience, satisfaction, and loyalty on students’ word-of-mouth and re-enrolment intentions. J. Mark. High. Educ. 32, 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1852469 (2022).

Pal, D. & Patra, S. University students’ perception of video-based learning in times of COVID-19: A TAM/TTF perspective. Int. J. Hum. –Comput Interact. 37, 903–921. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1848164 (2021).

Tsang, J. T., So, M. K., Chong, A. C., Lam, B. S. & Chu, A. M. Higher education during the pandemic: the predictive factors of learning effectiveness in COVID-19 online learning. Educ. Sci. 11, 446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11080446 (2021).

Ramsden, P. A performance indicator of teaching quality in higher education: the course experience questionnaire. Stud. High. Educ. 16, 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079112331382944 (1991).

Byrne, M. & Flood, B. Assessing the teaching quality of accounting programmes: an evaluation of the course experience questionnaire. Assess. Eval High. Educ. 28, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930301668 (2003).

Wilson, K. L., Lizzio, A. & Ramsden, P. The development, validation and application of the course experience questionnaire. Stud. High. Educ. 22, 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079712331381121 (1997).

Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 9, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajams-9-1-2 (2021).

Funding

This project was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Research Program of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (Project No. 25WYF484)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by YC and MW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MW. The revision was made by JN. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The research was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The research was approved by the local ethics committees of Guilin University of Technology.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Wang, M. & Ni, J. Educational benefits of laser scanning and 3D printing for studying and preserving Southeast Asian ceramic artifacts. Sci Rep 16, 1043 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30620-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30620-2