Abstract

Continuous kinematics estimation methods are important in human-machine interaction systems because they offer a more natural and intuitive result than pattern-recognition methods. The estimation of upper-limb movement is important, which involves the estimation of the movement of the elbow and shoulder joints. However, the deformations of muscles around the elbow and shoulder can cause the shifting of the angle sensors. Nevertheless, Vicon can measure joint angles using cameras that have no contact with muscles. In this paper, we propose a Linear-Attention-based model (LABD) rather than other deep learning models to estimate upper-limb movements. The sEMG signals were collected from eight sEMG sensors and angles were measured from Vicon. The experimental results of LABD were compared with multilayer perceptrons (MLP), Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), long short-term memory network (LSTM), and a dot-product attention-based model (DABD). The Pearson correlation coefficients (PCC) between the target and estimated joint angle sequences were calculated to evaluate the performance of each model. The Wilcoxon signed-rank results showed that the LABD significantly outperformed the other models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of robots has increased in recent years, this caused the booming attention attached by human-machine coordination in manufacturing, military, service delivery and other fields1,2,3, in this field, making the robot understand the movement of human is particularly important4,5. The computer vision-based methods6 and sEMG-based methods7 have been proposed and widely adopted several years ago. Actually, the computer version-based models often need fixed cameras and a bright environment, and the block of the body will significantly influence the prediction result. Also, the method needs a lot of computing resources and has a delay between the predicted result and the real movement. However, the sEMG-based models can acquire the kinematics in a few instants before the movement occurs and do not need the conditions required by the computer version-based models. The sEMG signals contain rich information about muscles and have a correlation with movements. sEMG has been used in human-machine interaction control systems for decades8,9,10, so the sEMG-based method was the focus of the study. However, the most widely used sEMG-based methods were myoelectric-pattern recognition techniques11, which are only able to provide discrete movement classification. Therefore, to provide continuous kinematic estimation, the sEMG-based simultaneous and proportional control method was proposed; the method provided continuous movement estimation, and it is closer to common human activities.

To achieve the goal of intuitive and natural control of robotic arms, Lin et al.12 employed wise non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) method based on the concept of muscle synergy to estimate kinematics from multichannel sEMG13, Qing et al.14 proposed a Hill-based muscle model that estimate continuous elbow angles from sEMG signals. Wang et al..15 used Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to acquire continuous hand kinematics of six movements from forearm sEMG signals. Actually, musculoskeletal base models need Complex calculations, so they are hard to be widely adopted in practical applications. The non-negative matrix factorization-based methods are usually used in whist movement estimation, and they provide a control matrix rather than joint angles. Most machine learning models use sensors to collect angles, which makes the collection of instabilities of the collected angles when muscles are moving. Moreover, the traditional models cannot analyze the time features and the relationship between different sEMG channels simultaneously, which cannot achieve a high estimation accuracy.

Thus, there is a need to find a novel method that can collect joint angles and estimate them accurately. Traditional angle sensors should be fixed in muscles; the movement of muscles may cause instabilities. The Motion Capture technology can measure angles without sensors fixed in muscles, and can calculate angles from the key point fixed in human joints, which makes the collection of joint angles more accurate. So we used a Motion Capture device to measure joint angles. We used the designed software to synchronize sEMG signals and joint angles to ensure the Neural signals and kinematics are synchronized. To make the accuracy higher, we employed the Linear-Attention16 in this study. Linear-Attention can extract the features of input data in 2 dimensions, so we chose to apply Linear-Attention and to compare it with the commonly adopted deep learning-based methods (MLP17, TCN18, LSTM19, and dot-production attention20).

Method

Subjects

The dataset used in this study was obtained from eight full-body individuals (all male, ages 24–40, all right-handed). None of the participants has any known neurological disorders. All participants read and signed an informed consent form before proceeding with the experiment. The experimental protocol and all methods adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of West China Hospital (#2022-505).

Experimental protocol

As introduced in the Introduction, to synchronize the sEMG signals and arm movements, the sEMG signals and angle measurements were obtained from the same arm, the sEMG signals were recorded by Noraxon (Noraxon Ultium EMG, China), and the angle measurements were obtained from Vicon(Vicon, England) and are synchronous by designed software.

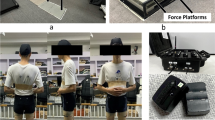

During the measurement, each subject was asked to sit down in front of a laptop displaying a repeated movement video. The eight sEMG sensors were placed in the anterior deltoid, the middle deltoid, the posterior deltoid, the biceps, the posterior triceps, the medial triceps, the pectoralis major, and the musculi supraspinatus, as shown in Fig. 2. The joint angles were captured from Vicon, and four angles were recorded and are shown in Table 1.

For target movements, four single DoF movements, three simultaneous multiple DoF movements, and a free movement were selected; they are functionally relevant and representative of most shoulder-elbow flexions, translations, and rotations in common. These are listed in Table 2. The subjects were told to sequentially perform the eight types of movements on the dominant arm, starting from the natural state with the arms extended, motionless, and palms facing forward. Subjects were asked to start and end each movement in the sequence by a prompt on a laptop screen. The subjects were instructed to imitate the movements shown on the screen, each movement repeated six times, and had a rest for at least 90 seconds between each movement, which ensured the quality of the sEMG signals acquired from the subjects.

The Noraxon (Noraxon Ultium EMG, China) and Vicon (Vicon, England) were used to acquire sEMG signals and angles. The Noraxon applied sEMG signals for 8 channels at sampling frequency of 2000Hz, The Vicon can measure all known joint angles in the human body. In this measurement, four needed angles were recorded and are mentioned in the first paragraph in this section. The Vicon recorded angles at a sampling frequency of 100Hz, and were resampled to 2000Hz after measurement. The synchrony of sEMG and angle sampling points was ensured by a designed software. 10Hz-500Hz Butterworth filter was applied to the recorded sEMG signals. The setup of the experiment is shown in Fig. 1.

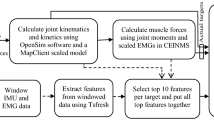

The root mean square value (RMS) feature was chosen as the feature extract from sEMG signals for it contains a great amount of information. The RMS feature was extracted by a window of length 100ms, and a step at 0.5ms. The RMS can be calculated using the following equation:

Where the N is the size of the window,\(n_i\) represents the \(i-th\) sampling point of the sEMG in the sliding window, and the \(\overline{n}\) represents the mean value of the data in the sliding window.

After the extract for the RMS, The \(\mu -law\) normalization was concluded. The \(\mu\)-law normalization21 amplifies the input sEMG data close to 0 using a logarithmic approach, allowing them to contribute more to the predicted results. Normalization of the \(\mu\) law has been shown to effectively improve the performance of the model to evaluate EMG signals. The \(\mu\)-law normalization formula is as follows:

where \(x_i\) is the t-th sampling point of the input, and the hyperparameter \(\mu\) decides the range after normalization.

Model development

Dot-product attention

Attention based model:The dot-product attention attention mechanism22 is introduced by Google cooperation in 2017. The mechanism has demonstrated exceptional performance in natural language processing. The mechanism is crucial in generating outputs based on the interdependence among the input vector sequences, which can extract the correlation from different sEMG channels and can generate a better angle. The dot-product attention is considered the most basic attention mechanism, so it was chosen to be in comparison as a baseline model in this study. The model computing formula has been displayed below.

Given the input matrix X with a dimension of \(l\times c\) , where l is the length of the input sequence and c is the number of sEMG channels in the experiment, l is set to 100ms. The attention layer generates the attention matrix with the same dimension as X, utilizing a set of parallel and independent heads. The attention layer contains three linear layers, and can generate the query matrix Q, key matrix K, and values matrix V, respectively. The corresponding formulas are defined as follows:

Where the \(W_q\),\(W_k\),\(W_v\) are three learnable matrices of size \(R^{l\times l}\),\(b_q\),\(b_k\),\(b_v\) are in \(R^{l\times c}\),\(d_k\) is a scalar value, which equals to the first dimension of \(W_q\), \(W_k\) and \(W_v\), the dot-product of two matrix Q and K are divided by \(\sqrt{d_k}\) .\(\alpha\) represents the attention matrix and was normalized to [0,1].

Linear-attention based model

Linear- Attention mechanism was first provided by Angelos in 202016, different from the dot-product attention mechanism, Linear Attention used the structure similar to RNN, which can deal with the sequence data better then other models, also the advantage of dot-product remained. Linear-Attention mechanism combines the advantages of RNN and dot-product attention, which makes it perform better in sEMG continues estimation.

Dot-product attention mechanism can calculate the relationship between every sEMG channel, but cannot understand the time feature in the sEMG data. The Linear-Attention overcomes the disadvantage.

In linear-attention mechanism, the attention layer was formalized as a recurrent neural network, the resulting RNN has two hidden states, namely the attention memory s and the normalized memory z. The formula has been subscribed to donate the timestep in the recurrence:

where \(x_i\) denotes the ith input and the \(y_i\) denotes the ith output for a specific transformer layer, the \(W_Q\) , \(W_K\) , \(W_V\) are three learnable matrices. The function elu() denotes the exponential linear unit.

As show in Fig. 3, the Linear-Attention use the structure similar to RNN, the \(s_{t-1}\) and \(s_t\) represent the attention memory output at time \(t-1\) and time t. The \(z_{t-1}\) and \(z_t\) represent the attention memory output at time \(t-1\) and time t also. They recorded the feature in previous sample points, this allows Linear-Attention mechanism to understand the sEMG signals better. The \(x_t\) represents the eight channels of sEMG in time t, \(x_t\) was calculated by the Linear-Attention cells then calculated by an exponential linear unit, this allow the Linear-Attention mechanism to understand the relationship between different sEMG channels and perform better in angle estimation.

The linear-attention based model is displayed in Fig. 3, as shown in the figure The output of Linear-Attention cell then calculated by a exponential linear unit, and then add to the raw input to prevent gradient vanishing and explosion23, then the output go though a full connect layer to get the output into a vector in \(1\times 4\) which related to four estimated angles.

Comparison of the models

The multilayer perceptron (MLP), considered to be the most basic neural network and has been used frequently in investigating human-machine systems24,25. Therefore, in this study, MLP has been chosen as the baseline model for comparison. The MLP has been shown to have the ability to fit a continuous curve or sequence value. In this study, three layers of non-fully connected networks were set as the hidden layers. The sEMG data was flattened into a 1-dimensional form before send into the neural network. The last two layers compressed the expanded data into 4 channels to predict the joint angles. Finally, to prevent the models from overfitting, the spatial dropout at 0.3 was added between each layer during training.

As a comparison model, we employ a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN)18. TCN utilizes stacked one-dimensional convolutional layers with dilated kernels to model long-range temporal dependencies in sequential data. Critically, they enforce causality—ensuring predictions depend solely on past inputs while enabling parallel computation over entire sequences, offering computational advantages over recurrent architectures. TCN had been used in previous studies26 and performed well in continuous angle estimation, so TCN was chosen as a comparison model.

Long Short-Term Memory network (LSTM)19, has been used in previous study. LSTM is a recurrent neural network (RNN) variant specifically designed with gating mechanisms (input, forget, output gates) and a cell state to learn long-term temporal dependencies in sequential data. This architecture effectively addresses the vanishing gradient problem inherent in standard RNNs, making it well-suited for modeling physiological signals like sEMG.

Settings

The backpropagation algorithm was chosen to be the training approach in this study. Both the dot product attention and Linear-Attention set the layer into 1 The LSTM layer was set to 3. the dropout value was set to 0.3, The dropout value was set to 0.3 to prevent overfitting. All models were trained for 300 epochs, the learning rete was set to 0.001 and half after 100 epochs during training. In this study, all hyper-parameters were chosen best performed from the grouped values.

In this experiment, the Friedman’s test27 and Wilcoxon’s sign rank test28 were used to evaluate the significance of the results.

Results

Before a detailed analysis of the proposed and comparison networks, a performance comparison was made. The input data used the \(\mu -law\) normalization and raw input data (as show in Table 5), the Table show the comparison of all models in this study.

As shown in Table 5 ,all models were greatly improved by adopting the \(\mu -law\) normalization, because it amplifies the input sEMG data close to 0 using a logarithmic approach, allowing them to contribute more to the predicted results. It has been demonstrated that\(\mu -law\) normalization can effectively improve he model’s performance for evaluating EMG signals .

After the comparison of raw input and \(\mu -law\) normalization, all models were developed in PyTorch29. All movements were combined, four repetitions of each movement were set as the training set and the remaining two repetitions were set as the testing set. All results are shown in Table 3. As an example, the performance of each model in subject 3 is compared in Fig. 4, which shows the variation of the measured joint angles and the estimated angles over time.

Panel (a) of the figure shows that the MLP model is hardly able to match the pattern of any of the four measured joint angles and particularly performed badly when estimating the SDV angle. The TCN model performed better, when the real joint angle became stable, the estimated joint angle became unstable. The LSTM performed better for the estimation of the elbow joint angle but it performed unwell for the SDV angle. The DABD performed better then the upper models but there was still somewhere inaccuracy in SBV and SDV angle. However, the LABD compensated for the shortcomings of the upper models, and achieved the best performance when compared. The Pearson correlation coefficient (cc) was used to provide a quantitative measure of the association between the estimated joint angles and real joint angles of each subject, as shown in Table 3.

To analyze the relevance of the features, we plot a line chart of predictions vs. the single input feature. The EBH angle depends mostly on the biceps, so we compared the angle with the RMS value extracted from the recorded sEMG data from the biceps, as show in Fig. 5, the rest angel and RMS figures were put in a github link (click the “github link” to view them), they have a similar trend, so all models performed well in EBH angle as shown in Fig. 4, While the rest angels depend on several muscles, so they do not have the similar trends with a single RMS channel. Our model can efficiently acquire information from different sEMG (RMS) channels, that is the reason our model performed well in the rest angles’ estimation.

We also reported the average CC value, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Dynamic Time Warping distance (DWT) in Table 4. Our method achieved the best performance in RMSE and DTW, while MLP performed the worse, which showed the complete advantage of our model LABD.

To evaluate the generalization ability of our method, we conducted the leave-one-subject-out tests, that is train the model on other 7 subjects and test on the left single subject, between our model and other models and reported the average performance (CC, RMSE and DTW) in Table 6, from the Table, our model LABD continues performed well in CC value, and performed almost the same as the model DABD and LSTM in RMSE and DTW, which means our model can be generalized in cross-subject tasks and has a better performance than the baseline models (TCN, MLP, and LSTM), this showed the potential of our model in cross-subject tasks.

The different methods showed significantly different performance on subjects according to the Friedman test. And the Wilcoxon signed-rank test result after Bonferroni correction indicated that the LABD(CC=0.9430) significantly outperformed the MLP (CC=0.8204, p=0.0419), the TCN (CC=0.8575, p=0.0374), the LSTM (CC=0.9015, p=0.0714) and the DABD (CC=0.9083, p=0.0799).

To evaluate the model from a deployment perspective, we tested the inference time of different models on different devices: CPU, GPU, and Raspberry Pi 4B. The results were shown in Table 7. From the table, the MLP and TCN achieved shorter inference time than our model in three kinds of devices and training time, but they have poor performance in model accuracy. Our model LABD, performed better than the LSTM and DABD models in inference time and training time, and well within the real-time requirement for human-machine interaction, which showed our model is suitable for real-time deployment.

Discussion

In this study, a Linear-Attention based model (LABD) was proposed, the method was used to obtain estimated joint angles from non-invasively collected sEMG signals, and compared to MLP, LSTM, TCN and DABD. The result of the experiment showed that LABD outperformed MLP, LSTM, TCN, and DABD in exploiting the kinematic information from sEMG signals in each case, and the differences were statistically significant.

The experiment show that, there is a great challenge in estimating the joint angles adequately using existing models. The MLP model cannot estimate the joint angles precisely because of its structure, the input data must be flattened at first, and the step makes the sEMG signal lose its information in the time dimension and channel dimension. TCN is a Convolutional Neural Network designed for time-series data. It can deal with sEMG signals better than traditional CNN models, but the Convolutional operation caused some unwanted noise. Compare to MLP and TCN model, the LSTM model can generate smoother and more accurate joint angles because its memory cell can combine prior information and current information, but the cell is too simple to deal with the sEMG information and cannot extract features from sEMG channels, which makes the joint angles decided by more than one channel badly estimated. Different from LSTM, the DABD can not only combine prior information but also can combine future information and the model structure is Sufficiently complex in dealing the sEMG signals, which make it outperformed than LSTM, but the DABD cannot extract features from sEMG channels as well as LSTM model. The proposed method: LABD, solved the problem due to its structure and yielded the best estimation results.

Conclusion

The proposed LABD model achieved a mean Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.94 (±0.02) and an RMSE of 3.75, outperforming MLP(0.82±0.2, p=0.0419), TCN (0.86±0.05, p=0.0374), LSTM (0.90±0.01, p=0.0714) and DBAD (0.93±0.04, p=0.0799), while our model parameters (0.68MB) and inference time (CPU: 8.36ms, GPU: 0.99ms, ARM: 22.97ms) are outperformed than the well-performed models (DABD and LSTM).

Though the synchronized measurements, the kinematic information acquired from sEMG signals can estimate the four joint angles of the upper-limb, the results show that the Linear-Attention based model achieved a significantly better accuracy than MLP, TCN, LSTM and dot-production models, the structure of LABD makes it own modest time and memory, the eight movements were used to ensure the model can estimate enough and broad movements.

The model was trained for every single subject, absolutely, the training strategy is complicated and makes it difficult to generalize. Cross-subject style can train a model across subjects and adapt to multiple subjects30. Transfer learning can use a small number of training epochs to reduce model training time by preserving similar parts between subjects. Our future work will focus on applying our methods to better performed cross-subject study, transfer learning and synthetic EMG data to improve robustness in scenarios with small sample sizes, as demonstrated in recent generative AI studies on rare diseases31. In short, our method is a outperformed and suitable approach for a single subject.

Data availability

The portion of the datasets generated during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository. https://sandbox.zenodo.org/records/393956?token=eyJhbGciOiJIUzUxMiJ9.eyJpZCI6IjYwODZlZjIzLTc3OGEtNDdhNS1hMGU5LTY2N2E4ZDg4OWM0ZSIsImRhdGEiOnt9LCJyYW5kb20iOiI3MmIwMjMwN2I2ZWZlMjk0YzdlY2ZlNTZjYjYzZmI3NiJ9.CPph_SC_zbnzThYMHIQyeSjguHhnn1dVb4gpJJSktMaa9wz5oKlvdq8GYTdbucNDBmHgn7OYeKYk91ZJIbY6qQ

References

Kuo, C.-M., Chen, L.-C. & Tseng, C.-Y. Investigating an innovative service with hospitality robots. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 29(5), 1305–1321. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2015-0414 (2017).

Noorman, M. & Johnson, D. G. Negotiating autonomy and responsibility in military robots. Ethics Inf. Technol. 16(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-013-9335-0 (2014).

Veloso, M., Biswas, J., Coltin, B. & Rosenthal, S. Cobots: Robust symbiotic autonomous mobile service robots. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI) . 4423–4429 (2015)

Oliveira, D. S. et al. A direct spinal cord-computer interface enables the control of the paralysed hand in spinal cord injury. Brain 147, 3583–3595 (2024).

Bi, L. Z., Feleke, A. G. & Guan, C. T. A review on emg-based motor intention prediction of continuous human upper limb motion for human-robot collaboration. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 51, 113–127 (2019).

Szabo, R. & Gontean, A. Controlling a robotic arm in the 3D space with stereo vision. In 2013 21th Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR). 916–919 (2013)

Farina, D. et al. The extraction of neural information from the surface emg for the control of upper-limb prostheses: Emerging avenues and challenges. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 22(4), 797–809. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2014.2305111 (2014).

Cho, K., Merrienboer, B.V., Gulcehre, C., Bahdanau, D., Bougares, F., Schwenk, H. & Bengio, Y.J.C.S. Learning phrase representations using rnn encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation (2014).

Montazerin, M. et al. Transformer-based hand gesture recognition from instantaneous to fused neural decomposition of high-density emg signals. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36490-w (2023).

He, Y.N., Fukuda, O., Bu, N., Okumura, H. & Yamaguchi, N. Surface emg pattern recognition using long short-term memory combined with multilayer perceptron. In 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE-Engineering-in-Medicine-and-Biology-Society (EMBC). 5636–5639 (2018)

Bien, Z. New emg pattern recognition based on soft computing techniques and its application to control of a rehabilitation robotic arm. (2000). https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:5827523

Chuang, L., Binghui, W., Ning, J. & Farina, D.: Robust extraction of basis functions for simultaneous and proportional myoelectric control via sparse non-negative matrix factorization. J. Neural Eng. 15 (2018)

Tresch, P. et al. The construction of movement by the spinal cord. Nat. Neurosci. 2(10), 162–167 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/5721.

Ding, Q.C., Xiong, A.B., Zhao, X.G. & Han, J.D. A novel emg-driven state space model for the estimation of continuous joint movements. In 2011 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. 2891–2897 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSMC.2011.6084104

Wang, C. et al. semg-based continuous estimation of grasp movements by long-short term memory network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2019.101774 (2020).

Katharopoulos, A., Vyas, A., Pappas, N. & Fleuret, F. Transformers are rnns: Fast autoregressive transformers with linear attention. In International Conference on Machine Learning (Daume, H., Singh, A. eds.) . Vol. 119. (2020).

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 2(5), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/0893-6080(89)90020-8 (1989).

Lea, C., Flynn, M.D., Vidal, R., Reiter, A. & Hager, G.D. Temporal convolutional networks for action segmentation and detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2017)

He, Y., Fukuda, O., Bu, N., Okumura, H. & Yamaguchi, N. Surface emg pattern recognition using long short-term memory combined with multilayer perceptron. In 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). 5636–5639 (2018)

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N., Kaiser, L. & Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need (2023). arXiv:1706.03762.

Rahimian, E. et al. Fs-hgr: Few-shot learning for hand gesture recognition via electromyography. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 29, 1004–1015. https://doi.org/10.1109/tnsre.2021.3077413 (2021).

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N., Kaiser, L. & Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS). Vol. 30 (2017)

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition (2015). arXiv:1512.03385.

Muceli, S. & Farina, D. Simultaneous and proportional estimation of hand kinematics from emg during mirrored movements at multiple degrees-of-freedom. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 20(3), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2011.2178039 (2012).

Chu, J.-U., Moon, I. & Mun, M.-S. A real-time emg pattern recognition based on linear-nonlinear feature projection for multifunction myoelectric hand. In 9th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics, 2005. ICORR 2005. 295–298 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICORR.2005.1501105.

Chen, C. et al. SEMG-based continuous estimation of finger kinematics via large-scale temporal convolutional network. Appl. Sci.-Basel https://doi.org/10.3390/app11104678 (2021).

Azman, N., Syarif, A., Brahmia, M.-e.-A., Dollinger, J.-F., Ouchani, S. & Idoumghar, L. Performance analysis of rpl protocols in lln network using Friedman’s test. In 2020 7th International Conference on Internet of Things: Systems, Management and Security (IOTSMS) (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/IOTSMS52051.2020.9340203.

Sahoo, U.K., Panda, G. & Mulgrew, B. Sign-regressor Wilcoxon and sign-sign Wilcoxon. In 2010 International Conference on Advances in Recent Technologies in Communication and Computing. 35–39 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/ARTCom.2010.37.

Ketkar, N. Introduction to PyTorch. 195–208. (Apress, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-2766-4_12 .

Chen, X. J., Guo, W. Y., Lin, C., Jiang, N. & Su, J. Y. Cross-subject lifelong learning for continuous estimation from surface electromyographic signal. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 32, 1965–1973 (2024).

Trabassi, D. et al. Optimizing rare disease gait classification through data balancing and generative AI: Insights from hereditary cerebellar ataxia. Sensors 24(11), 24 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants who completed this study.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2024A1515011688); in part by the Shenzhen Municipal Science and Technology Innovation Bureau under its General Project (Grant No. JCYJ20250604140051064); and in part by the Postdoctoral Later-Stage Funding of Shenzhen Polytechnic University (Grant No. 6023271024K1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chuang Lin, Ming Dai and Chunxiao Zhao proposed an experimental approach and designed a research plan. Chunxiao Zhao transformed their ideas into a practical experiment. Chuang Lin provides guidance on the writing approach of the article and checks the rigor of its expression. Na Li helped complete the measurement of the sEMG and angle signals. All authors reviewed the manuscript. Consent for publication was given by all participants.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the West China Hospital (#2022-505). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, C., Zhao, C., Li, N. et al. A linear-attention based network for estimating continuous upper limb movement from surface electromyography. Sci Rep 16, 1100 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30665-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30665-3