Abstract

The aim of the study was to determine the effect of sonication with different levels of total acoustic power (250 W and 500 W) on the physicochemical and biochemical properties of beef and red deer meat. The parameters related to meat colour, surface myoglobin forms, antioxidant properties and the level of fat and protein oxidation were analysed. The results showed that the sonication significantly affected meat colour, myoglobin forms, antioxidant capacity, and oxidative markers, particularly in beef. Beef treated with 500 W sonication exhibited a significant decrease in redness (a* value reduced by 20%) and increase in yellowness (b* value increased by 21.5%), resulting in a total colour difference (ΔE*) increase of 3.42 ± 0.35 units compared to controls. Red deer meat changes were less evident, with a notable rise in oxymyoglobin content (%OMb increased by 7.85%) at 500 W. Protein carbonyl content decreased by 12.4% and 6.9% after sonication at 250 W and 500 W respectively. TBARS values were lower in beef than in deer meat; 250 W sonication reduced TBARS by 29.5% in case of beef and 13.58% in red deer meat, whereas 500 W increased lipid oxidation by 6.5% and 4% respectively. The antioxidant activity of the studied meat extracts increased after the application of 500 W sonication. In conclusion regardless of the type of meat, the highest oxidative stability is demonstrated by samples that were exposed to sonication at a total acoustic power level of 250 W. In addition, red deer meat is less susceptible to sonication process than beef. This study advances understanding of sonication effects on meat quality, providing insights that can improve processing techniques and extend product shelf life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultrasound has the potential to be used in the food industry. Depending on the category (high-intensity and low-frequency, medium-intensity and intermediate-frequency, low-intensity and high-frequency) as well as method of applying (direct application, coupling to a device or immersion in ultrasound bath) various outcomes are achieved1,2. The effects of ultrasound on food quality depend heavily on the processing parameters, such as acoustic power, frequency, and exposure time. Improper selection of these parameters can lead to adverse effects, including increased oxidation of lipids and proteins, which negatively impacts colour, texture, and overall shelf life3. Studies have shown that higher ultrasound power levels can cause changes in mechanical, physical or chemical properties of the product, for example modifying its texture, affecting enzyme and bacterial activity, disrupting cell walls and releasing their contents as well as leading to changes in the secondary structure of the proteins4,5,6,7,8,9. This indicates the need for careful optimisation of sonication conditions in order to achieve a balance between the beneficial and harmful effects of ultrasound, which is crucial for its effective application in food technology.

In meat processing, ultrasound treatment is used to accelerate the brining process, improving the sensory properties (colour, texture) and technological parameters like water-holding capacity or pH5,10,11. Additionally, the effect of ultrasound on the inhibition of bacterial growth or enhancement on enzyme activity, is important in the field of meat preservation and can affect the shelf life and safety of products12. From the other side, some undesirable effects of using ultrasound in meat technology have also been reported. Kang et al.13 observed that an increase in ultrasound power caused greater oxidation of lipid and protein fractions in beef muscle during the brining. A similar relationship was observed by Peña-González et al.14, who reported that after 14 days of storage, ultrasound-treated beef exhibited a significant increase in lipid oxidation compared with untreated samples. In some cases, a negative effect of sonication on raw beef colour parameters has also been noted, including a reduction in redness together with an increase in lightness and yellowness5,15. Nevertheless, all changes occurring under the influence of ultrasound depend on the process parameters (e.g. exposure time and intensity); therefore, selecting appropriate conditions can minimise undesirable effects. Moreover, the composition of the meat matrix, including its type, species and origin, determines its susceptibility to sonication. Thus, the application of ultrasound technology in meat processing requires an individual approach and optimisation of process parameters for each type of meat4.

Although the application of ultrasound has been increasingly explored in meat science, most studies to date have focused on its technological effects in conventional livestock species such as beef, pork, or poultry, particularly in processed or marinated systems16. These studies have mainly examined tenderness, water-holding capacity and emulsification properties rather than the underlying oxidative mechanisms. In contrast, there is a lack of information on how sonication influences the redox balance, myoglobin forms, and oxidative stability of raw game meat, which differs markedly from livestock, for example, due to its higher myoglobin content and distinct fatty acid profile. Therefore, the present study provides a novel comparative approach by investigating the physicochemical and biochemical responses of red deer and beef semimembranosus muscles to ultrasound treatment at different acoustic power levels. This research aims to fill the current knowledge gap by elucidating the effects of sonication on colour stability, protein and lipid oxidation. The use of this technology to improve the quality of game meat may increase its consumer acceptance and market potential, which is particularly important for both economic and nutritional reasons.

According to OECD-FAO Agriculture Outlook17 projected consumption of meat proteins will increase by 14% by 2030 in comparison to consumption in 2018–2020. Moreover, predictions indicate in developed countries, consumers will increasingly choose higher-value meats due to changes in food preferences as well as an aging population. This growing demand for meat proteins and changing consumer awareness is driving the search for alternative meat sources that meet current needs. One of the undervalued sources of meat is venison, which, compared to beef, is characterized by higher protein content with a more favourable amino acid profile and significantly lower fat content18. In addition, due to the wildlife habitat or, in the case of farm animals, the preferred extensive nature of breeding, as well as limited contact with pharmaceuticals, venison is considered safe to consume and organic19. Poland harvested 11,268 tons of carcasses from wild game (leaving aside farm animals) of which about 73% was venison (53% red deer and 20% of roe deer)20. Unfortunately, due to the low consumption of venison in Poland (about 0.08 kg per person per year) about 95% of purchased venison is exported abroad21. Effect of sonication on meat quality parameters such as texture parameters (reduction of shear force values and improving tenderness) and use of this technology to facilitate cooking processes could help improve consumer acceptance of this meat and, in the long run, increase deer meat consumption.

It was hypothesised that appropriately selected sonication parameters can positively impact the quality of meat products, which is particularly important in the case of game meat due to its specific properties that limit consumption. In this study, this hypothesis was tested in relation to selected meat quality parameters, i.e., colour and oxidative stability, in order to compare the effects of sonication in red deer meat and beef.

Material and methods

Raw meat

Animal material for research was obtained post-mortem, no individual was killed solely for research purposes and therefore ethics committee approval is not required. To eliminate sex-related factors affecting meat quality, the study material included meat from both females and males, which were treated as a single experimental group. Red deer meat (musculus semimembranosus (SM)) was obtained from a deer farm in Rudzie (Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship; Poland), where the animals lived in natural environmental conditions and were killed by shooting according to the owner’s preferences for consumption purposes. The meat came from 6 animals (3 males and 3 females) aged 3–4 years. Beef samples were obtained from six Limousin cattle (three males and three females) with a live weight of approximately 400–450 kg, raised under organic farming conditions. The animals were slaughtered in a slaughterhouse, where the samples were vacuum packed and transported under refrigerated (4 °C) and light-protected conditions directly to the analytical laboratory. All samples were fresh (not frozen) and prepared 48 h post-mortem. During this time, they were stored and transported at 4 °C to maintain quality prior to sonication.

Sample preparation

The meat for analysis was cleaned of fascia, tendons and protruding muscle fragments. The meat was washed with tap water. As shown in Fig. 1, from each type of meat (beef and red deer) and each carcass from three spindle-shaped pieces of meat (∼200 g) were removed from the SM muscle. These were individually packaged in a sealed vacuum bag and randomly assigned to one of the following treatments: C—control, no ultrasonic treatment; 250S—treated with a 40 kHz wave and a total acoustic power of 250 W, and 500S—treated with a 40 kHz wave and a total acoustic power of 500 W. All samples, regardless of species, were processed under identical conditions and during the same experimental session to ensure comparability. As a result, 6 study groups were formed (2 types of meat × 3 treatments) with 6 pieces of meat from different animal carcasses per group. All sonication treatments were conducted using a Polsonic device (Warsaw, Poland). All samples (including controls) were placed in distilled water as a diffusion medium and processed during the same experimental session. The temperature of the medium was continuously monitored with a temperature probe and maintained at 8 ± 2 °C by the periodic addition of crushed ice when necessary. The exposure time for both sonicated and control samples was 4 min. Ultrasonication was performed in continuous mode (without pulse modulation).

Measurements

pH

The meat samples were prepared in an aqueous solution, and the pH was measured directly in this solution immediately after preparation. The pH was evaluated with a digital pH meter CPC-501 (Elmetron, Zabrze, Poland) equipped with a temperature sensor and pH electrode (ERH-111, Hydroment Gliwice, Poland). The pHmeter automatically compensated for temperature in measurements and was calibrated with pH 4.01, 7.00 and 9.21 buffers at 23 °C. The pH measurements were made in triplicate.

Colour parameters

Colour assessment was performed immediately after the sonication treatment, using X-Rite Colour Premiere 8200 spectrophotometer (X-Rite Inc., MI, USA). X-Rite white and black standards were used for pre-measurement calibration. The measurement was conducted using the following parameters: D65 illumination (daylight, 6500 K), standard observer 10°. The instrumental conditions were a 12-mm-diameter area aperture. The measure was taken immediately after cutting the sample across, using recommended by the CIE (Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage) colour space L*a*b* (L* (lightness), a* (redness) and b* (yellowness). Other colour parameters, i.e. Ch* (chroma) and h° (hue angle) were calculated using the standard equations:

The measurement was carried out ten times for each sample.

Total colour difference (∆E) was calculated between control samples (non-sonicated samples) and beef (C-250S and C-500S) or red deer (C-250S and C-500S) samples under sonication according to the formula:

where:

In the interpretation of ΔE results, it was assumed that when 0 < ΔE < 1, the observer does not notice the difference; when 1 < ΔE < 2, only an experienced observer may notice the difference; when 2 < ΔE < 3. 5, an inexperienced observer also notices the difference; when 3.5 < ΔE < 5, a clear difference in colour is noticed; and when ΔE > 5, an observer notices two different colours.

Surface myoglobin forms

During the measurements of colour parameters, the surface reflectance was recorded at the wavelengths from 400 to 700 nm with 10nm intervals. The reflectance data were used to calculate the surface levels of myoglobin (Mb) forms (metmyoglobin (MMb), deoxymyoglobin (DMb) and oxymyoglobin (OMb)) after integration of reflectance for the required wavelengths according to the method described by American Meat Science Association22. In brief the spectral reflectance data R(λ), were converted into spectral attenuance A(λ) using the formula:

Following this, the percentage of each myoglobin form is calculated using specific equations, where A is spectral attenuance at the specified wavelength:

Protein carbonyl content

The assay was performed using the Protein Carbonyl Content Assay Kit (MAK094) in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. The results were expressed as nmol carbonyl/mg protein. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Protein and peptide content

The content of peptides was determined using the trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) method23. The results were determined on the basis of a standard curve prepared for L-leucine as the reference amino acid. The content of proteins in the precipitate was determined by the Bradford’s method24. The results were calculated using a standard curve prepared for bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a reference protein. The results were expressed as mg/ml. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Lipid oxidation

The content of 2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) was used to analyse lipid oxidation. The measure was made sixfold, according to the technique described by Pikul et al.25 using perchloric acid as a solvent. Results were expressed as equivalent of mg of malondialdehyde (MDA) per kilogram of sample. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Total antioxidant capacity

Total antioxidant capacity was tested on meat extracts. The meat sample was homogenized with distilled water on ice in a ratio of 1:9. and left for extraction for one hour at 4 °C. After this time, the homogenate was centrifuged at 5000×g for 30 min at 4 °C. TAC was measured in extracts obtained using radical-scavenging 2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS·+) activity according to Re et al.26, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH·) according to Wu et al.27; and reducing power (RP) according to Mora et al.28 as well as ferrous iron-chelating activity according to Decker and Welch29. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were analysed using Statistica version 13 software (Dell Inc., 2016) and expressed as the mean ± standard error. The experimental design was a 3 × 2 factorial in a completely randomized design with three treatments (without sonication (C) or sonicated with different total acoustic power—250 W (250S) and 500 W (500S)) and two species of meat (beef and red deer) as main effects. Factorial ANOVA was used to analyse the effect of categorical factors (type of meat, treatment) and interactions between them treated as fixed effects, with carcass as a random effect. Cochran C, Hartley, and Bartlett test were used for checking the homogeneity of variances. Post-hoc comparisons were made using Tukey’s test. The significance level of the differences was P ≤ 0.05. The principal component analysis (PCA) method was used to graphically present the relationship between the quality factors. The correct use of PCA was confirmed by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test for sampling adequacy and the Bartlett sphericity test (results no shown).

Results

The levels of statistical significance of the main factors (type of meat, sonication parameters (different levels of total acoustic power) as well as their interactions on the research parameters are indicated in Table 1. The type of meat is not a factor that significantly influences Fe-chelation, carbonyl group and protein content as well as parameters related to the colour of the samples such as yellowness, chroma, hue angle and percentage of deoxymyoglobin form. The sonication process significantly affected almost all the studied parameters except for the lightness of the sample (L*). The interaction between these factors (type of meat and sonication process) strongly influenced (P ≤ 0.001) the pH, parameters related to antioxidant properties (DPPH, Fe-chelation, TBARS, carbonyl group content) as well as parameters related to the colour of the samples (redness and yellowness, chroma and dynamics of myoglobin redox form interconversions (%DMb, %OMb, %MMb)).

pH, colour parameters, surface myoglobin redox states

A significant interaction between the type of meat and sonication method on the pH of fresh meat was identified in this study (P < 0.05; Table 1). It was shown that the pH of beef was significantly higher than that of deer. Moreover, the use of the 500 W sonication parameter lowered the pH of both types of meat (P < 0.05; Table 2).

Chroma (Ch*), Hue angle (h°)) for fresh beef and red deer meat without sonication and after sonication with different acoustic intensity (250 W and 500 W) were detected. A significant effect the type of meat on lightness (L*) of the meat was found, and the lightness of the beef meat was greater than that of the deer (P < 0.05; Table 3).

The sonication process had no effect on the quality of the fresh meat (P > 0.05; Table 1). A significant interaction of type of meat × sonication method on a*, b*, Ch* and h° was found (P < 0.05, Table 4). The ultrasound affected the saturation index (Chroma) of beef, lowering its value from 16.77 for control sample to 13.99 and 13.35 for the samples treated with 40 kHz wave frequency 250 W and 500 W of total acoustic power respectively (P < 0.05; Table 4).

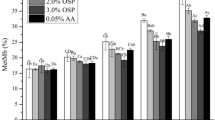

Based on the obtained results, it was observed that sonication had a significantly greater effect on the parameters related to meat colour in the case of beef. Although almost all results for colour coordinates (a*, b*, Ch*) were similar for different variants of red deer meat, in the case of beef, a significant effect of ultrasonic treatment was observed on the reduction of redness (a*) and yellowness (b*) compared to the control sample. This is in line with the results of the calculations for ΔE where in beef meat, total colour differences between control and ultrasound-treated samples were almost five times higher than in red deer samples (Fig. 2). The differences in the ΔE parameter values for the deer and beef samples indicate that the change in the colour of beef meat under the influence of sonication will also be noticed by an inexperienced observer (ΔE value between 2–3.5), while in the case of deer meat, the difference is not noticeable even by an experienced observer (ΔE under 1).

Total colour difference (∆E) between control samples and beef (C-250S and C-500S) or red deer (C-250 WS and C-500S) under sonication. 250S—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 250 W condition; 500S—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 500 W condition. Different letters a-b indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard errors.

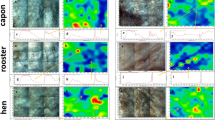

Type of meat and sonication method affected surface myoglobin forms (P < 0.05, Table 5). In the case of surface myoglobin redox states, in beef ultrasound treatment lowered the percentage of metmyoglobin and oxymyoglobin form, whereas the deoxymyoglobin content was higher in samples after sonication. These changes were more intense when using higher total acoustic power parameters (P < 0.05). In the case of deer meat an increase in oxymyoglobin after 500 W acoustic intensity of sonication was observed while the percentage of deoxymyoglobin and metmyoglobin remained statistically unchanged.

Oxidative status and antioxidant potential

The significance of the interaction of type of meat × sonication method on protein carbonyl content is presented in Table 1 (P < 0.05). Protein carbonyl content is an indicator of chemical changes in the protein fraction resulting from oxidative changes. A higher value of protein carbonyl content was shown in the beef sample than in the red deer (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the effect of sonication on the reduction of protein carbonyl content in beef samples (C vs. 250S = 500S, P < 0.05), but not in red deer samples (C = 500S; 250S = 500S; P > 0.05), was noted. The amount of total acoustic power used (250 W vs. 500 W) had no effect on this parameter within the type of meat. However, the use of total acoustic power in the amount of 500 Was associated with a higher protein carbonyl content in the red deer sample (500S) compared to beef samples with this same treatment (500S; P < 0.05).

Protein oxidation status of beef and red deer meat treated with ultrasound: C—non-sonicated samples; 250 W—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 250 W condition; 500S—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 500 W condition. Different letters a-c indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05). Error bars represent the standard errors.

The degree of oxidative changes in protein components in beef and red deer meat may result from their different levels in muscle tissue. However, no significant changes were noted in the protein content considering the type of meat (P > 0.05, Table 1). On the other hand, a strong interaction was found between the factors considered in this study, i.e., meat type × sonication method, as shown in Table 6. In the case of red deer meat, sonication significantly reduced the protein content of fresh meat compared to the control group, regardless of the total acoustic power level used (250 W or 500 W).

The main effects also had a significant impact on peptide content (Table 1; P < 0.05). Taking into account the influence of the type of meat (Table 7, P < 0.05), a higher peptide content was determined in the case of red deer compared to beef. In turn, the use of sonication at a higher dose of acoustic power (500 W) significantly reduced the peptide content, regardless of the type of meat subjected to ultrasound (Table 8, P < 0.05).

The beef samples were characterized by lower content of secondary fat oxidation products defined by the TBARS value, compared to red deer variants (P < 0.05). Moreover, it was found that the application of sonication of raw beef and deer meat with a dose of total acoustic power 250 W significantly reduced the TBARS value, while the dose of 500 W intensifies the oxidation processes of the fat fraction of meat (Fig. 4).

Lipid oxidation status of beef and red deer meat treated with ultrasound: C—non-sonicated samples; 250S—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 250 W condition; 500S—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 500 W condition. Different letters a-d indicate significant difference (P < 0.05). Error bars represent standard errors.

A significant interaction of type of meat × sonication method on ABTS, DPPH and Fe- chelating activity was found (P < 0.05, Table 1), and results are presented in Table 9. The analysis included, among others, the antiradical activity of extracts against synthetic radicals ABTS·+ and DPPH·. It was shown that regardless of the type of meat (beef or red deer), higher radical scavenging activity was determined against ABTS·+ radicals than DPPH·. The effect of the total acoustic power dose at the level of 250 W on the antiradical activity of beef and deer extracts against ABTS·+ was not confirmed. On the other hand, an increase in antiradical activity was observed in beef and deer samples under the influence of the total acoustic power at the level of 500 W in this test. However, in the analysis with DPPH·, a significant increase in the antiradical activity was observed with increasing total acoustic power (C < 250 WS < 500S). A slightly different trend was noted in the case of the ability of meat extracts to chelate iron ions, i.e., a decrease in the discussed activity under the influence of a lower dose of total acoustic power (250 W) in the beef sample (P < 0.05), while the 500S variant (beef) did not differ significantly from the control (C, beef). In relation to extracts from red deer meat samples, the effect of total acoustic power at the level of 500 W significantly (P < 0.05) increased the chelating capacity in relation to the other variants (P < 0.05).

Only the main effect influenced the reducing power measured in beef and deer meat extracts (P > 0.05, Table 1). The effect of the type of meat on the reducing power of raw beef and deer meat was confirmed (Table 10; P < 0.05), and higher RP was determined for deer meat samples. Also, sonication method affected RP of raw meat, as presented in Table 11 (P < 0.05). The sonication treatment contributed to the reduction of RP, but this effect was not proportional to the applied total acoustic power, i.e. a lower reducing capacity was noted in the samples subjected to higher total acoustic power (500 W).

Principial components analysis (PCA) results

To provide a partial visualization of the data such as pH and aw value, colour parameters (L*, a*, b*, haem iron, %MMb, %DMb, %OMb, chroma and hue angle) as well as oxidation parameter (protein carbonyl group, TBARS), antioxidant status (ABTS, DPPH, Fe-chelating and RP) or protein and peptides content in raw beef and red deer meat, a PCA was performed (Table 12, Fig. 5A, B). The PCA results showed that the first two principal components explained 54.65% of the cumulative variance. The variables that correlated most with PC1 included colour traits such as %MMb, %DMb and sample redness (a*) and chroma, as well as carbonyl group content (Table 12). Figure 5A showing loadings for the two principal components indicates that except for %DMb (square III), all variables were strongly (above 0.700) positively correlated with the first component (square I or II). The second principal component explained 22.60% of the cumulative variance and included a positive effect of the colour trait—hue angle and the oxidative index related to the lipid fraction of meat, i.e., TBARS. A strong positive correlation was observed between these variables (square IV). On the other hand, pH was negatively correlated with PCA2. It is worth emphasizing the strong correlation between pH and the antiradical activity of the samples, which can be seen in square II of the graphical presentation of the PCA analysis.

(A) Loadings for the two principal components. %MMb—% metmyoglobin; % DMb—% deoxymyoglobin; % OMb—% oxymyoglobin; L*- lightness; a*- redness; b*- yellowness; chroma–chroma (Ch*); hue–hue angle (h°); pH—acidity; ABTS—antiradical activity against ABTS·+; DPPH—antiradical activity against DPPH·; RP—reducing power; Fe–Fe2+-chelating activity; carbonyl content–protein carbonyl content; TBARS—2-thiobarbituric acid reactive substances level; haem iron–haem iron content; protein–protein content; peptides–peptides content.] (B) Projection of cases on the factor plane. Cases from the same group of meat and treatment were classified according to the type of meat (B—beef, D—red deer) and sonication condition (C—non-sonicated samples; 250 W—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 250 W condition; 500—samples sonicated under total acoustic power 500 W condition).

The projection of cases on the factorial plane (Fig. 5B) shows the location of cases in the multidimensional space of two principal components (PCI and PCII). Considering PCI, cases are basically divided into two areas, the first one being the BC variant and the second area being the remaining variants. These two areas show some variability, since the non-sonicated beef samples, placed on the right side of the graph (Fig. 5B), were characterized by higher pH, a*, b*, chroma, hue angle (Table 4), %MMb, %DMb (Table 5) and oxidation indices (Figs. 3, 4) or iron ion chelating capacity (Table 9) compared to the non-sonicated deer meat. Considering the distribution of samples with respect to PCII, cases are basically divided into two groups, which included two types of meat. The distribution of grouped points for red deer meat was located in the upper part of the graph, while the arrangement of variants in groups for beef formed a separate area in the lower part of the graph. The samples of deer meat exposed to total acoustic power of 500 W and beef exposed to 250 W are furthest apart, which indicates the greatest difference between these samples in the parameters correlated with PC2.

Discussion

Our study is one of the primary research studies about the changes that occur during ultrasound treatment of red deer raw meat. The most important meat quality characteristics are pH, sensory characteristics and oxidative stability. Acidity is one of the key raw meat quality indicators, as it directly affects protein stability and properties. The pH level of raw beef and deer meat was typical for the species after slaughter. Considering the effect of sonication, beef was more susceptible to the effect of a total acoustic power dose of 500 W, where a decrease in pH of 0.33 units was noted compared to the control. At the same time, exposure of meat with a total acoustic power dose of 250 W did not affect the discussed parameter for both beef and red deer meat (Table 2). Similarly, Stadnik and Dolatowski15 showed that ultrasound treatment did not have a statistically significant effect on the pH of the beef (m. semimembranosus) after sonication (45 kHz; 2 W/cm2, 2 min) in samples 24 h post mortem. However, these authors showed, after this period of time, sonicated samples tended to increase in comparison to the control variant with increasing time (up to 72 h post mortem)15. The influence of aging time on pH changes of sonicated meat may explain differences in trends presented by other authors. According to Jayasooriya et al.30, pH of longissimus lumborum and semitendinosus muscles exposed to ultrasound (24 kHz, 12 W/cm2) remained unchanged after 8.5 days of cold storage. Also, Carrillo-Lopez et al.31 showed no significant differences in pH of beef under the influence of ultrasonic bath (37 kHz, 550 W, 90 W/cm2) or probe system (400 W, 24 kHz, continuous pulse and 100% amplitude) in samples of longissimus lumborum after 7 days of refrigerated storage31. These observations are identical to the results of Caraveo et al.5, who showed no effect of sonication on beef for 10 days of storage (4 °C). During sonication, ultrasound is generated causing acoustic cavitation, which is the phenomenon of generation, growth and eventual collapse of bubbles, which is accompanied by thermal, mechanical and chemical effects. The mechanical effects include collapse pressure, turbulence caused by the acoustic flow and shear stress. The main chemical effect is the formation of radicals under extreme temperature and pressure conditions. Indeed, in our study, the effect of sonication on the protein and fat oxidation profile was noted, with differences in total carbonyl content (used as a protein oxidation indicator) characterizing the red deer meat samples being statistically insignificant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 3). Studies presented by Kang et al.13 indicate that ultrasound leads to structural changes and oxidation of beef proteins due to mechanical effects of cavitation and the resulting generation of free radicals. The mentioned authors suggest that the use of sonication increased protein aggregation via disulphide cross-linking, as indicated by the decreasing content of total sulfhydryl groups, which could contribute to protein oxidation. Furthermore, changes in protein structure following sonication are suggested by an increase in free sulfhydryl residues and protein surface hydrophobicity13. However, in contrast, the present study indicates a reduction in protein carbonyl content in sonicated samples (without affecting the process parameters) of beef, whereas deer meat remains unaffected by ultrasound-induced protein oxidation processes.

In the present study, there was also an increase in thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in meat samples treated with a total acoustic power of 500 W, indicating that the sonication process induced fat oxidation at high intensities. On the other hand, a total acoustic power dose of 250 W caused a decrease in the TBARS index (Fig. 4). This may indicate that, in addition to sonochemical oxidation, reduction also occurs, as noted by Yasui32. Despite the fact that the main reducing agent (hydrogen atom) formed as a result of the dissociation of water is located inside the cavitation bubble, it is possible to produce a reducing agent by chemical reaction with OH radicals generated from cavitation bubbles in aqueous solutions with the addition of organic substances. This is what can happen in the case of sonication of fresh meat, whose water content is quite high and contains many organic substances that can take part in the formation of reducing agents32. Results for lipid oxidation status suggest that using a total acoustic power dose of 250 W leads to the predominance of sonochemical reduction processes over oxidation. Meat colour is one of the most important visual characteristics for consumers and producers. Especially in the case of fresh beef, cherry-red colour is necessary for consumer acceptance. At the biochemical level, the colour of meat is determined by the concentration of the main pigment of the cardiac and skeletal muscles—myoglobin (hereinafter referred to as Mb), consisting of a protein component (globin), a prosthetic component (heme) and the ratio of its redox forms in muscle tissue33. As the oxidation of the muscle surface progresses, the colour of the meat will change from red to brown due to the accumulation of metmyoglobin. Therefore, the oxidative status of meat affects not only its safety from consumption but also consumer acceptability. Based on the ΔE value (which is the resultant of L*, a* and b*; ΔE > 3.5), the meat sonication process does not affect the colour change of the meat that could be noticed by the consumer, which is consistent with the other reports33. However, deer meat was less susceptible to ΔE changes under the influence of sonication than beef. Many factors that affect the colour and colour stability of meat have been reported, such as post-mortem conditions and processing, packaging method, temperature of storage and many others22. However, there are limited studies on the colour stability of wild animal meat or the effect of ultrasound on the colour of this meat raw material34. Some reports suggest that ultrasound is neutral because it has no effect on meat colour35. Conversely, in the evaluation of the effect of ultrasound (22 W/cm2) on meat, the colour was shown to change to a lighter, less red and more yellow-orange (higher hue angle), which was darker than in the control meat36. Ultrasound has also been reported to accelerate the overall colour changes, reduce the formation of oxymyoglobin, and slow down the formation of metmyoglobin in products15. Myoglobin is a protein responsible for the colour of meat, depending on the interconversions of forms in fresh meat it can exist in three redox states DMb, MMb and OMb. The main influence on the redox state of myoglobin forms is oxygen consumption and metmyoglobin reducing activity (MRA) which are directly dependent on mitochondrial function37.

The sonication process leads to the formation of reactive oxygen species and free radicals formed as a result of cavitation. In view of this, sonication should promote the formation of oxidized forms of myoglobin and therefore metmyoglobin and oxymyoglobin, but our results indicate that the opposite is true. In the case of beef, the sonication process significantly decreased MMb and OMb content in favour of DMb concentration, indicating oxygen consumption and thus increased mitochondrial activity. The increased activity of mitochondria is also supported by the fact that the intensity of mitochondria activity is related to pH (an increase in pH enhances mitochondrial activity)22,37. In our case, changes in the redox forms of myoglobin indicating the processes of oxygen consumption are more intensely observed in beef meat, characterized by a higher pH than deer meat. This is also in line with the results obtained for the protein carbonyl content where the sonication process reduced the content of carbonyl groups limiting their oxidation, and the changes are greater for beef than for deer meat. When considering the type of meat, it appears that red deer meat is more resistant to radicals formed during sonication (Tables 9, 10) than beef, as the ultrasound-induced changes were less intense. Thus, less advanced changes in protein oxidation are associated with less radical-induced changes within the fat fraction. Indeed, lipid peroxidation products such as malondialdehyde and carbonyl compounds can react with proteins to form carbonyl groups38. Delles and Xiong39 reported that secondary lipid oxidation products (dicarbonyl) can bind to myosin to form protein-bound carbonyls. However, taking into account possible reduction processes related to activity of mitochondria, MRA as well as formation of alkaline compounds with the OH group originating from cavitation bubbles, lower changes in the case of red deer indicate the reduction and oxidation processes taking place are balanced whereas in case of beef reduction processes dominated.

Conclusion

The sonication process affects the parameters related to the oxidation state of the meat, showing a varied effect on the oxidation processes taking place. Considering the protein carbonyl content, as well as the redox forms of myoglobin, the sonication process favours sonochemical reduction processes over oxidation. Regardless of the type of meat, the highest oxidative stability is demonstrated by samples that were exposed to sonication at a total acoustic power level of 250 W. In addition, red deer meat is less susceptible to sonication. Thus, sonication significantly affects the physicochemical and biochemical properties of meat, and these changes were more pronounced in beef than in red deer meat. The results can be used in the future to develop a procedure for extending the shelf life of red deer meat by controlling its oxidative status. This study provides the first comparative insight into how ultrasound affects the oxidative balance and colour stability of red deer and beef meat. These outcomes offer a new perspective for the sustainable application of ultrasound in meat processing, particularly in the context of alternative protein sources such as game meat. Additionally, it would be valuable to expand research on the application of sonication to red deer meat during processing, particularly in relation to enhancing sensory attributes such as tenderness and juiciness.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Bhangu, S. K. & Ashokkumar, M. Theory of sonochemistry. In Sonochemistry. Topics in Current Chemistry Collections (eds Colmenares, J. & Chatel, G.) 1–28 (Springer, Cham, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54271-3_1.

Gallo, M., Ferrara, L. & Naviglio, D. Application of ultrasound in food science and technology: A perspective. Foods 7(10), 164 (2018).

Awad, T. S., Moharram, H. A., Shaltout, O. E., Asker, D. Y. M. M. & Youssef, M. M. Applications of ultrasound in analysis, processing and quality control of food: A review. Food Res. Int. 48(2), 410–427 (2012).

Alarcon-Rojo, A. D., Carrillo-Lopez, L. M., Reyes-Villagrana, R., Huerta-Jiménez, M. & Garcia-Galicia, I. A. Ultrasound and meat quality: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 55, 369–382 (2019).

Caraveo, O., Alarcon-Rojo, A. D., Renteria, A., Santellano, E. & Paniwnyk, L. Physicochemical and microbiological characteristics of beef treated with high-intensity ultrasound and stored at 4 °C. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95(12), 2487–2493 (2015).

Huang, R. et al. Research advance of application of ultrasonic treatment in meat processing. Shipin Gongye Keji 44(20), 431–439 (2023).

Lee, E. Y. et al. Effect of novel high-intensity ultrasound technique on physio-chemical, sensory attributes, and microstructure of bovine semitendinosus muscle. Food Sci. Animal Resour. 43(1), 85–100 (2023).

Turantaş, F., Kılıç, G. B. & Kılıç, B. Ultrasound in the meat industry: General applications and decontamination efficiency. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 198, 59–69 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Changes in collagen properties and cathepsin activity of beef M. semitendinosus by the application of ultrasound during post-mortem aging. Meat Sci. 185, 108718 (2022).

Li, K., Kang, Z. L., Zhao, Y. Y., Xu, X. L. & Zhou, G. H. Use of high-intensity ultrasound to improve functional properties of batter suspensions prepared from PSE-like chicken breast meat. Food Bioprocess Technol. 7, 3466–3477 (2014).

Zou, Y., Zhang, W., Kang, D. & Zhou, G. Improvement of tenderness and water holding capacity of spiced beef by the application of ultrasound during cooking. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 53(3), 828–836 (2018).

Barekat, S. & Soltanizadeh, N. Improvement of meat tenderness by simultaneous application of high-intensity ultrasonic radiation and papain treatment. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 39, 223–229 (2017).

Kang, D. C. et al. Effects of power ultrasound on oxidation and structure of beef proteins during curing processing. Ultrason. Sonochem. 33, 47–53 (2016).

Peña-González, E. M. et al. Quality and sensory profile of ultrasound-treated beef. Ital. J. Food Sci. 29(3), 463–475 (2017).

Stadnik, J. & Dolatowski, Z. J. Influence of sonication on Warner-Bratzler shear force, colour and myoglobin of beef (m. semimembranosus). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 233, 553–559 (2011).

Çimen, N., Unal, K. & Alp, H. Effects of ultrasound-assisted marination on spent hen meats: Microstructure, textural and technological properties. Food Biosci. 61, 104563 (2024).

OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021–2030 (OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1787/19428846-en.

Bureš, D., Bartoň, L., Kotrba, R. & Hakl, J. Quality attributes and composition of meat from red deer (Cervus elaphus), fallow deer (Dama dama) and Aberdeen Angus and Holstein cattle (Bos taurus). J. Sci. Food Agric. 95(11), 2299–2306 (2015).

Mason, F., Fotschki, B., Di Rosso, A. & Korzekwa, A. Influence of farming conditions on the rumen of red deer (Cervus elaphus). Animals 9(9), 601 (2019).

GUS 2024. https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/tablica. Available 20 Feb 2025.

Ankudo-Jankowska, A. & Starosta-Grala, M. Game meat procurement market in Poland in 2009–2021. Acta Sci. Pol., Silvarum Colendarum Ratio et Industria Lignaria 21(1), 13–20 (2022).

King, D. A. et al. American Meat Science Association guidelines for meat color measurement. Meat Muscle Biol. 6(4), 1–81 (2023).

Adler-Nissen, J. Determination of the degree of hydrolysis of food protein hydrolysates by trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 27, 1256–1262 (1979).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilising the principle of protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Pikul, J., Leszczynski, D. E. & Kummerow, F. A. Evaluation of three modified TBA methods for measuring lipid oxidation in chicken meat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 37(5), 1309–1313 (1989).

Re, R. et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radical Biol. Med. 26(9–10), 1231–1237 (1999).

Wu, H. C., Chen, H. M. & Shiau, C. Y. Free amino acids and peptides as related to antioxidant properties in protein hydrolysates of mackerel (Scomber austriasicus). Food Res. Int. 36(9–10), 949–957 (2003).

Mora, L., Escudero, E., Fraser, P. D., Aristoy, M. C. & Toldrá, F. Proteomic identification of antioxidant peptides from 400 to 250 W0 Da generated in Spanish dry-cured ham contained in a size-exclusion chromatography fraction. Food Res. Int. 56, 68–76 (2014).

Decker, E. A. & Welch, B. Role of ferritin as a lipid oxidation catalyst in muscle food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 38(3), 674–677 (1990).

Jayasooriya, S. D., Torley, P. J., D’arcy, B. R. & Bhandari, B. R. Effect of high-power ultrasound and ageing on the physical properties of bovine Semitendinosus and Longissimus muscles. Meat Sci. 75(4), 628–639 (2007).

Carrillo-Lopez, L. M., Cruz-Garibaldi, B. Y., Huerta-Jimenez, M., Garcia-Galicia, I. A. & Alarcon-Rojo, A. D. The physicochemical, microbiological, and structural changes in beef are dependent on the ultrasound system, time, and one-side exposition. Molecules 27(2), 541 (2022).

Yasui, K. The reducing agents in sonochemical reactions without any additives. Molecules 28(10), 4198 (2023).

Krasulya, O. et al. Estimation of the stability of skeletal muscle myoglobin of chilled pork treated with brine activated by low-frequency high-intensity ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 71, 105363 (2021).

Chakanya, C., Arnaud, E., Muchenje, V. & Hoffman, L. C. Colour and oxidative stability of mince produced from fresh and frozen/thawed fallow deer (Dama dama) meat. Meat Sci. 126, 63–72 (2017).

Sikes, A. L., Mawson, R., Stark, J. & Warner, R. Quality properties of pre-and post-rigor beef muscle after interventions with high frequency ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 21(6), 2138–2143 (2014).

Pohlman, F. W., Dikeman, M. E. & Kropf, D. H. Effects of high intensity ultrasound treatment, storage time and cooking method on shear, sensory, instrumental color and cooking properties of packaged and unpackaged beef pectoralis muscle. Meat Sci. 46(1), 89–100 (1997).

Ramanathan, R. & Mancini, R. A. Role of mitochondria in beef color: A review. Meat Muscle Biol. 2(1), 309–320 (2018).

Estévez, M. Protein carbonyls in meat systems: A review. Meat Sci. 89(3), 259–279 (2011).

Delles, R. M. & Xiong, Y. L. The effect of protein oxidation on hydration and water-binding in pork packaged in an oxygen-enriched atmosphere. Meat Sci. 97(2), 181–188 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.K: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, resources, validation, visualisation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing.Anna J. K.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, validation, writing-review and editing. Anna D.K: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, validation, visualisation, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kononiuk, A.D., Kęska, P. & Korzekwa, A.J. Improvement of colour and oxidative stability of red deer and beef meat under sonication treatment. Sci Rep 16, 1180 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30764-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30764-1