Abstract

Coral reefs are essential for the foundation of marine ecosystems. However, ocean acidification (OA), driven by rising atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) threatens coral growth and biological homeostasis. This study examines two Hawaiian coral species—Montipora capitata and Pocillopora acuta to elevated pCO2 simulating OA. Utilizing pH and O2 microsensors under controlled light and dark conditions, this work characterized interspecific concentration boundary layer (CBL) traits and quantified material fluxes under ambient and elevated pCO2. The results of this study revealed that under increased pCO2, P. acuta showed a significant reduction in dark proton efflux, followed by an increase in light O2 flux, suggesting reduced calcification and enhanced photosynthesis. In contrast, M. capitata did not show any robust evidence of changes in either flux parameters under similar increased pCO2 conditions. Statistical analyses using linear models revealed several significant interactions among species, treatment, and light conditions, identifying physical, chemical, and biological drivers of species responses to increased pCO2. This study also presents several conceptual models that correlate the CBL dynamics measured here with calcification and metabolic processes, thereby justifying our findings. We indicate that elevated pCO2 exacerbates microchemical gradients in the CBL and may threaten calcification in vulnerable species such as P. acuta, while highlighting the resistance of M. capitata. Therefore, this study advances our understanding of how interspecific microenvironmental processes could influence coral responses to changing ocean chemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With rising atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) from anthropogenic activities, observations indicate decreasing ocean pH and aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) along with increasing the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2), a process known as ocean acidification (OA)1,2,3. Future predictions (AR6; B.1.3; Scenario SSP5-8.5) for the years 2081–2100 show that surface pH levels of the North Pacific Ocean are ‘virtually certain’ to decrease by 0.28–0.29 units, resulting to a median value of 7.70 pH units4. This shift would increase hydrogen ion concentrations ([H+]) by nearly ~ 100%, following the standards presented by the IPCC (2022) in the year 21005. Seawater chemistry is tightly linked to calcifying organisms ability to precipitate calcium carbonate (CaCO3) skeletons1,2,3,5,6. Such calcification has been observed in scleractinian corals under acidification at both the ecosystem7,8,9,10,11 and individual scales12,13,14,15,16. However, more importantly, responses are not uniformly shared among species15,16,17, and interact with environmental factors such as irradiance13 and seawater movement surrounding coral colonies18,19. Coral calcification under OA varies empirically, ranging from + 45% to −100% relative to ambient conditions, therefore, identifying the driver(s) of response is of the utmost importance for addressing the ongoing climate crisis20,21,22. To bridge this gap, interspecific responses show promise when considering morphology and the influence thereof on localized boundary layers (BL) at various depths from the surface of the coral23,24. This study aims to test this postulate through discrete measurements of proton and oxygen (O2) flux within the smallest BL of Montipora capitata and Pocillopora acuta, both classified as branching corals, but differ greatly in microtopography (Fig. 1).

Stereoscope images of living corals in seawater or skeletal fragments. Shown from left to right, (a) Montipora capitata skeletal fragment (complex), with the white bracket indicating the zone of primary calcification (ZPC), (b) M. capitata tissue surface, (c) Pocillopora acuta skeletal fragment (robust) with ZPC indicated by a white bracket, and (d) P. acuta tissue surface. The white scale bar in each image is representative of ~ 1 mm.

Bulk advection barriers, where diffusion becomes the dominant mass-transfer process surrounding the coral, may act as an interspecific property that drives physical and chemical limitations to calcification. This study refers to this physical diffusive barrier as the concentration boundary layer (CBL), a thin, quiescent seawater layer surrounding the coral18,25,26. The CBL has been established in M. capitata (previously: M. verrucosa), localized to ~ 2.0 mm above the coral surface27 and shown in recent literature to be as small as ~ 0.1–0.2 mm thick in branching corals Acropora cytherea, Pocillopora verrucosa, and Porites cylindrica25. Several studies have explored CBL diffusion limitations using flow speed, calcifier taxa, morphology, and light/dark scenarios as proxies to explain the biological drivers of environmental change from OA18,19,25,28,29.

Across coral species, morphological comparisons such as branching or mounding19 and small-polyp or large-polyp corals driving CBL differences have been well studied30,31. Shown less frequently are the CBL dynamics between small-polyped coral species25,31. However, recent reports have highlighted ciliary vortices that disrupt the CBL in small-polyp coral species under slow flow32,33. Microtopographic differences influencing CBL dynamics, including corallite size and density among small-polyped species have only recently been established in Martins et al.31. For reference, M. capitata has corallites spaced ~ 25 polyps cm− 2 at ~ 2 mm in diameter, more sparse than those of P. acuta, which are ~ 70 polyps cm− 2 at ~ 1 mm in diameter (Fig. 1b, d)34,35. Morphologies within complex or robust groups have also not been compared frequently in CBL analysis, where perforate skeletons in M. capitata and imperforate skeletons in P. acuta may drive differences in the CBL (Fig. 1a, c). Montipora capitata has shown resistance to elevated pCO2 and several other environmental stressors, potentially due to plastic internal physiological mechanisms13,17,34,36,37. Conversely, Pocillopora spp. has shown variable responses, with some reports showing a 26% decrease in calcification under OA12. This study uses both species to characterize CBL characteristics linked to known OA sensitivity and the micromorphological constraints in localized environments where calcification is dominant.

Branching corals calcify rapidly at the distal ends of their branches, and their symbionts are least present in this region, termed the zone of primary calcification (ZPC; Fig. 1a, c)23. Within the ZPC, calcification may be less reliant on photosynthesis and more on diffusion23. The dissipation of calcification inhibitors (e.g., H+), the influx of substrates (e.g., Ca2+ and DIC), or the diffusion of gases such as O238 could impose microchemical limitations on calcification23,26. Changes in ocean chemistry induced by OA may have severe negative consequences for diffusion-limited microenvironments at the ZPC18,23,25,26,31. Several biogeochemical hypotheses related to OA’s effects on coral calcification have been circulated, where the more prevalent adversity has been regarded as the depletion of [CO32−] ions, a consequence of decreased seawater Ωarag2,39,40. Although not always considered, oceanic [H+] ions will simultaneously increase, and reduced proton efflux from the calcifying fluid (cf.) and overlying tissues may further limit coral calcification26,41. Supporting the latter, molecular reports have found no CO32− ion transporters in corals42,43, calcification shows a higher sensitivity to bicarbonate ion concentrations ([HCO3−]) over other DIC species44, and the ratio of [HCO3−]: [H+] explains coral calcification better compared to Ωarag45. The fundamental nature of OA’s interaction with calcification in corals remains poorly elucidated. This study advances our understanding of how proton flux is affected by increasing OA, an emerging ideology grounded in the biological interpretation of chemical limitations to coral calcification.

Measurements of flux within the CBL have previously been used as a proxy for characterizing the internal physiological responses to acidification. Comeau et al.18 showed that CBL pH measurements can provide indirect correlations with the internal chemistry of the cf., such as the pHcf. and Ωcf.18. Hohn and Merico46 also reported increased leakage or diffusion through paracellular pathways connecting to the CBL, influencing the pHcf. and [CO32−]. Venn et al.47 concluded that the immediate microenvironment influences pHcf. through its effects on the basal side of the calicodermis. Jokiel et al.23 proposed a two-cell model for the ZPC in which diffusion is primarily linked to exporting the calcification inhibitor H+ (protons), supporting Jokiel26 on the boundary layer limitations from proton flux under OA23,26. Therefore, CBL measurements at the ZPC of branching corals may provide insight into the internal physiological processes directly associated with rapid calcification, and how calcification may be impacted by the diffusion limitations imposed by OA.

Material flux, as defined by Fick’s first law of diffusion, states that the diffusion of materials occurs from high to low concentration areas. Proton flux at the ZPC is essential for coral calcification and for maintaining internal pH chemistry that supports the precipitation of aragonite23,26. However, under OA, proton flux from the boundary layer encounters a shallower diffusive gradient due to the increase in external [H+]26. Interspecific microtopographic attributes discussed previously may define flux conditions for material exchange within the boundary layer. O2 flux has been addressed in CBL analysis among most current reports25,32,33, but proton flux has not yet been examined through direct measurements in the ZPC of branching corals. Furthermore, interactions between O2 and proton flux in the immediate microenvironment at the ZPC have not been explored. This study fills this gap by characterizing the microchemical influence of acidified seawater chemistry on the CBL, identifying interspecific material flux limitations, and creating internal physiological assumptions based on external measures.

In this study, we examined the microenvironment of two Hawaiian coral species, M. capitata and P. acuta, under OA in both light and dark conditions. Using genotypically identical corals, this study compares control and elevated pCO2 (OA) treatments to assess interspecific responses. By simultaneously measuring pH and O2, we hypothesize that microchemical gradients at the ZPC would reveal interspecific physiological constraints on internal calcification under OA19. Building on previous work by Comeau et al.18 and Martins et al.25,31, this study further elucidates the microenvironmental factors that regulate coral calcification.

Results

Proton flux and CBL thickness

A linear mixed model (LMM) with genotype as the random factor revealed no significant interaction with genotypes (duplicated across treatments). This model was simplified, dropping genotype (as an individual ID and as a blocking factor for the tank effect) as a random factor. The proton CBL thickness (Eqs. 1, 2) differed significantly between light and dark conditions (three-way ANOVA, f = 5.04, df = 1, p = 0.036; Fig. 2a, b). However, there was no strong evidence to suggest that increased pCO2 treatment (three-way ANOVA, f = 0.02, df = 1, p = 0.876) and species (three-way ANOVA, f = 4.03, df = 1, p = 0.058) differed in proton CBL thicknesses (Fig. 2a, b). Residuals deviated from normality, however, a robust linear model subsequently produced the same significant levels.

Boxplots of the proton ([H+]) boundary layer thickness (µm; Eqs. 1, 2) in both coral species, Montipora capitata (a) and Pocillopora acuta (b). Box color distinguishes treatment (Control = ambient, ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification), and the shaded region distinguishes light from dark conditions. Values are represented as individual profiles, with points, and the first and third quartiles are shown as boxes, with the median and whisker lines indicating the minimum and maximum. Significant differences are denoted as letters below the x-axis.

An LMM with genotype and tank interactions produced a singular fit for proton flux, random factors were dropped similarly to CBL thickness. The linear model with interactive effects (lowest AIC compared to the additive model) produced residuals that slightly deviated from normality, a Box-Cox Yeo-Johnson transformation (accounting for negative values) was applied to refit the model, and significance levels did not deviate (Fig. 3a, b). Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni-adjusted p-values revealed significant differences among several levels of treatment, condition, and species (Fig. 3a, b; Table S1). Strong evidence for an isolated treatment effect to elevated pCO2 was observed only in P. acuta under dark conditions, where efflux decreased relative to group means (Fig. 3a; three-way interaction ANOVA, est. = 8.17e− 5, df = 16, p = 0.047). Compared across species and conditions, dark-driven proton efflux in control P. acuta differed significantly from all groups (Table S1). Elevated pCO2 showed strong evidence to support increased light-driven proton influx in P. acuta that differed from the control group M. capitata (Fig. 3a, b; three-way interaction ANOVA, est. = 8.13e− 5, df = 16, p = 0.049). In contrast, there was no strong evidence to suggest that the control groups differed in the light condition between species.

Boxplots of proton flux (µmol m− 2 s− 1; Eq. 3) in both coral species, Montipora capitata (a) and Pocillopora acuta (b). Box color distinguishes treatment (Control = ambient, ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification), and the shaded region distinguishes light from dark conditions. Values are individual flux values per profile, represented as points, and boxes are the first and third quartiles with the median and whisker lines indicating the minimum and maximum. Arrows indicate flux direction, the green arrow (positive values) is efflux from the coral surface, and the red arrow (negative values) is influx to the coral surface. Significance between groups was denoted by letters below the x-axis.

O2 flux and CBL thickness

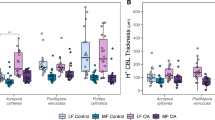

The [O2] CBL thickness (Eqs. 1, 2) was assessed using a LMM, with genotype and tank as random factors. We did not find strong evidence to support differences in [O2] CBL thickness across species, treatment, and condition (Fig. 4a, b).

Boxplots of the oxygen ([O2]) boundary layer thickness (µm; Eqs. 1, 2) in both coral species, Montipora capitata (a) and Pocillopora acuta (b). Box color distinguishes treatment (Control = ambient, ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification), and the shaded region distinguishes light from dark conditions. Values are represented as individual profiles, with points, and the first and third quartiles are shown as boxes, with the median and whisker lines indicating the minimum and maximum.

An LMM analysis of oxygen flux showed that genotype did not significantly contribute to explaining the data, therefore, similar in nature to the analysis of proton flux, this factor was omitted. The model with interactions had the lowest AIC score, and all p-values were calculated via pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni-adjusted values. On the treatment level comparison, there was strong evidence to support the effect of increased oxygen flux by ~ 40% change in P. acuta under light conditions (Fig. 5b; three-way interaction ANOVA, est. = −139, df = 16, p = 0.033). Between-species oxygen efflux under increased pCO2 in light conditions for the species P. acuta was significantly increased from all measures (Fig. 5a, b; Table S2). Dark oxygen influx significantly differed in the control group P. acuta compared to both treatment groups of M. capitata, whereas, under increased pCO2, oxygen influx in P. acuta did not differ between the treatment groups of M. capitata (Fig. 5a, b; Table S2).

Boxplots of the oxygen flux (µmol m− 2 s− 1; Eq. 4) in both coral species, Montipora capitata (a) and Pocillopora acuta (b), box color distinguishes treatment (Control = ambient, ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification), and the shaded region distinguishes light from dark conditions. Arrows indicate flux direction, the green arrow (positive values) is efflux from the coral surface, and the red arrow (negative values) is influx to the coral surface. Values are represented as individual profiles, with points, and the first and third quartiles are shown as boxes, with the median and whisker lines indicating the minimum and maximum. Significance between groups was denoted by letters below the x-axis.

Surface oscillations of pHT and [O2]

An interaction-based LMM with genotype as a random factor and Bonferroni pairwise adjusted p-values on the surface pHT values revealed strong evidence for light-driven pHT in P. acuta in the control group but not under increased pCO2. The mean ΔpHT = 1.02 for the control was nearly halved with a ΔpHT = 0.54 for the increased pCO2 group (Fig. 6b; Table S3). Furthermore, the control groups surface pHT of P. acuta in dark conditions was significantly lower than that of M. capitata, at pHT = 7.10 ± 0.12 and pHT = 7.61 ± 0.06 SD, respectively (Fig. 6a, b). There was no strong evidence to suggest that increased pCO2 significantly acidified the surface of the corals in both light and dark conditions (Fig. 6a, b; Table S3).

Slope dot plots comparing the mean ± SE (points) surface (0 μm) pH total (pHT; a, b) and concentrations of oxygen ([O2] mg L− 1; c, d) between dark and light conditions (shaded regions) for species Montipora capitata and Pocillopora acuta in response to treatment (Control = ambient, ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification). Letters adjacent to points indicate significantly different means with respect to the measure of either pHT or [O2] mg L− 1. Any shared letters among groups indicate means that were not significantly different, where letters that do differ were resulting significant groups. Slope lines show individual genotypic variation relative to the means and are distinguished by line type.

A second LMM with an identical design as the pHT analysis on the [O2] levels provided strong evidence for light-driven changes in surface [O2] for both species, whereas treatment had no significant impact under increased pCO2 (Fig. 6c, d; Table S4). However, increased pCO2 significantly increased the mean [O2] by 5.9 mg L− 1 for P. acuta compared to M. capitata in the light conditions (Fig. 6c, d; Table S4).

Calcification rate

A two-way ANOVA showed no strong evidence to support a significant impact on the calcification rates of both M. capitata and P. acuta. Nevertheless, comparisons of means showed a Δ calcification rate of −0.11 g CaCO3 d− 1 in P. acuta, which was notably greater than M. capitata at a Δ calcification rate of −0.04 g CaCO3 d− 1 (Fig. 7).

A bar plot of calcification rates in the change of buoyant weight over the 19-day exposure period. Bars represent the mean (N = 3) ± SE and are grouped by species, Montipora capitata and Pocillopora acuta. Bar color shows treatment where uncolored = control or ambient conditions, and grey = ↑pCO2 or ocean acidification conditions. There was no evidence of significant differences among the groups.

Discussion

Characterization of the CBL is essential for understanding the direct impacts of environmental stress on coral species and may explain observed responses. However, species comparisons (particularly branching small-polyped corals) seldom include CBL measurements as a response to environmental stress. In this study, CBL profile traits revealed reduced proton efflux in P. acuta but not M. capitata under elevated pCO2 measured in the distal and rapidly calcifying areas. Calcification data from previous studies show that M. capitata is more resistant to OA whereas P. acuta is more vulnerable12,13,17. Reduced dark proton efflux and thus increased interstitial [H+] could determine interspecific calcification sensitivities to increased seawater pCO223,26,41. We hypothesize that: (1) reduced dark proton efflux reflects decreased calcification due to increased seawater [H+] ions and potentially increased interstitial [H+], (2) O2 efflux increased under light conditions due to increased photosynthetic rates, and (3) microchemical extremes within the CBL induced by species micromorphology was a major factor for interspecific responses observed.

Proton and oxygen flux

This study conducted measurements within the ZPC, which, for morphologically branching corals, is constrained to the distal tips of each branch, primarily contributing to linear extension and rapid calcification23,41. Material exchange (flux) between the coral organism and seawater within the ZPC is essential for maintaining the internal processes such as calcification, photosynthesis, and respiration46,48,49,50. Under elevated pCO2, proton efflux in P. acuta was on average significantly repressed by 84% from ~ 2.5 to ~ 0.4 (µmol m− 2 s− 1 × 104) in dark conditions. On the other hand, the species M. capitata exhibited little to no change in proton efflux under elevated pCO2, resulting in a non-significant Δ from ~ 0.29 to ~ 0.27 (µmol m− 2 s− 1 × 104) in dark conditions. These findings suggest interspecific differences in proton flux, can be constrained and simplified into two internal processes, calcification and respiration (Fig. 8).

Conceptual model of hypotheses (H0-H4) for reduced proton (H+) efflux in dark conditions under ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification. The arrow and equation text size represent the magnitude of flux, where thinner arrows with smaller text indicate lower flux and thicker arrows with larger text show greater flux.

To understand the physiological processes dictating differences in dark proton efflux observed in this study, hypotheses H0-H4 were evaluated to suggest the impacts of elevated pCO2 (Fig. 8). A species comparison indicated that M. capitata aligned strongly with H0, whereas P. acuta could fall within the bounds of H1-H4. However, contrasting to Comeau et al.51, there was no strong evidence for decreased dark [O2] flux, and thus no indication of reduced dark respiration. Therefore, the results here support eliminating reduced dark respiratory rates (H2 and H3) as primarily contributing to differences in dark proton efflux (Fig. 8). This leaves H1 and H4, both of which position calcification as the primary driver of changes in dark proton efflux. Testing H4 independently with data collected here is not possible and has not been achieved in any previous microchemical investigations. However, increased dissolution rates would similarly correspond to decreased calcification rates, preventing net precipitation of CaCO3. Results in this study therefore support H1, proton flux driven reduced dark calcification rates, as the most likely scenario, given the decoupling of oxygen flux and the absence of reduced respiration rates. Nevertheless, oxygen flux increased significantly increased from ~ 205 to ~ 344 (µmol m− 2 s− 1) under light conditions, prompting a secondary set of postulates including respiration during the light conditions (Fig. 9).

Conceptual model of hypotheses (H0-H3) for increased oxygen (O2) efflux in light conditions under ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification. The arrow and equation text size represent the magnitude of flux, where thinner arrows with smaller text indicate lower flux and thicker arrows with larger text show greater flux.

The species M. capitata showed strong evidence consistent with H0 for O2 flux, shown by the conceptual model under elevated pCO2 (Fig. 9). However, the response observed in P. acuta, may follow trends in H1, H2, or H3 (Fig. 9). Based from the previous postulates, results suggest no indication of decreased dark respiration rates, supporting the elimination of H2 and H3 from the discussion (Fig. 9). Although this study did not measure light-enhanced dark respiration (LEDR), previous work has found no impact of elevated pCO2 on LEDR in the coral species Pocillopora verrucosa, Porites irregularis, Massive Porites spp., and Psammocora profundacella in Comeau et al.51, or Acropora millepora in Kaniewska et al.52. Given the increase of [O2] efflux, this suggests that photosynthesis must occur at normal or elevated rates, independently of respiration (Fig. 9). LEDR is thermodynamically enhanced by the availability of carbohydrate (CH2O) and would not be limited by photosynthesis. Therefore, we are inclined to reject H2 and H3 where LEDR was decreased. An increase in photosynthesis would align with findings in P. damicornis reported by Strahl et al.53, where corals were acclimated at CO2 seep sites, but this contrasts with the results found by Comeau et al.51 in an identical species comparison.

This study proposes that the driver of decreased calcification under elevated pCO2 is not metabolism (photosynthesis or respiration), but rather the ability to maintain proton efflux against a BL limitation (Fig. 10). The results in this study support a boundary layer limitation of proton flux under elevated pCO226,41 in the distal, rapidly calcifying regions of P. acuta but not M. capitata. Comeau et al.18 found that pHcf. and its relationship with CBL seawater pH vary among species and are additionally influenced by flow and light. The work here agrees with interspecific differences in CBL response to seawater pH, but may be limited by unexplored relationships to flow and light18,54. Contrasting with results here, the pH of the CBL and, thus, internal pHcf. has been shown not to be the primary driver for reduced calcification in corals55,56,57. Nevertheless, this study demonstrated that proton flux decreased significantly under elevated pCO2 and proposes this result as a function of reduced calcification. However, further work is needed to determine the cf. response correlated with proton flux in P. acuta to better understand how the microchemical external environment may influence internal chemical gradients.

Conceptual model of final proposed hypotheses for significantly increased oxygen (O2) efflux in light conditions, decreased proton efflux in dark conditions, no significant difference (n.s.) in the surface of the coral—change (Δ) pH total (pHT), and a significant (sig.) difference the surface Δ oxygen (O2) concentrations under ↑pCO2 = ocean acidification. Arrow thickness is represents the magnitude of flux.

In light of the O2 flux findings, the results of this study contrast with those of Martins et al.25, who reported no effect of OA on O2 flux in similar Pocilloporid spp. under higher flow regimes than those used in the present study. Allemand et al.58 discussed the link between calcification and photosynthesis. They proposed a model in which carbonic anhydrases59,60,61 in the coral symbionts to fix HCO3− as a source of DIC for photosynthesis. Their model further showed that OH− produced by hydrolysis buffers H+ ions generated from calcification58. In this study, O2 flux increased significantly in P. acuta under elevated pCO2, which is hypothesized to have resulted from increased photosynthesis. The availability of substrates for photosynthesis increases with elevated pCO262,63, and photosynthesis may benefit from this increased DIC pool64. Nevertheless, this study also observed the relative decrease in proton flux related to decreased calcification, which in turn could contribute toward reduced competition between host and algal symbionts for this shared DIC pool65. Future studies should continue to investigate whether elevated pCO2 directly stimulates photosynthesis or if reduced calcification provides less competition for DIC.

Absolute surface oscillations

To characterize diel fluctuations of pHT and O2 levels within the coral microenvironment, this study compared the absolute surface values under light and dark conditions at elevated pCO2 for both species. The results here indicated that at 0 μm (surface level), pHT differed significantly between light and dark conditions only in the control group of P. acuta. The magnitude of pH oscillations has been shown to predict the response of corals and coral communities to acidification66,67. Enochs et al.68 demonstrated that a bulk seawater pHT of 7.80 ± 0.20 produced harmful nighttime effects on calcification. This tipping point was surpassed in P. acuta under dark conditions and may be related to the reduction shown in proton flux.

Chan et al.19, showed that net coral response depends on the diel influence of pH in the microchemical environment. Greater pH oscillations result in dark extremes that may offset the benefits of elevated daytime pH. Naturally occurring high oscillations in temperature and pH have previously been shown to confer resistance to environmental change in corals69,70,71. The corals in this study were collected from a lagoonal system in Kāneʻohe Bay, Hawai’i, where natural oscillations are far greater than reefs within the archipelago (see morning and mid-day comparisons within Table 1)72,73. Notably, the calcification data in this study provided no compelling evidence to suggest that elevated pCO2 depressed bulk calcification values. Therefore, both species exhibited some degree of resistance to elevated pCO2, as calcification rates were nearly identical between species in the control treatments. However, P. acuta exhibited decreased dark proton efflux along with surface oscillations that were nearly halved compared with the control. The diminished oscillations in surface ΔpHT, decoupled from ΔO2 under elevated pCO2, suggest calcification limitations driven by seawater acidification rather than metabolism. Because P. acuta naturally exhibits high oscillations in ΔpHT and ΔO2, dark period thresholds may far exceed the tolerance limits of this coral under elevated pCO2.

Interspecific properties

Vertical profiles for both species were characterized as diffusive, complex, and S-shaped (Fig. 11a-d)31. However, CBL thicknesses did not differ significantly between species for either O2 or pH. Visibly, the profiles in P. acuta were highly complex or S-shaped in most cases, where notably, the microtopography of this coral species has larger and more dense polyps than M. capitata34,35,74. Montipora spp. also have tissue thicknesses six times thicker than those of Pocillopora spp. (~ 608 μm and ~ 183 μm, respectively)75. Ocean acidification can induce changes in microtopography, including polyp size76 and potentially ciliary activity32,77. Pacherres et al.32, demonstrated that ciliary vortices were essential for oxygen diffusion and flux surrounding the cenosarc. Future studies should investigate whether an increase in oxygen flux under OA is linked to a decreased capacity of cilia to diffuse oxygen. Coupling oxygen and proton flux measurements with particle image velocimetry, as applied by Pacherres et al.32, could elucidate cilia behavior and its relationship with external mass exchange.

In species comparisons, little has been documented regarding CBL characteristics of branching small polyp corals25,27. This study aimed to show CBL traits in dissimilar microtopographic complexes between macromorphologically similar species. Slow flow (1250 μm/s) produced anoxia (0.57 ± 0.08 O2 mg L− 1) in dark conditions of P. acuta and never reached a [O2] < 3.8 mg L− 1 in M. capitata. Shashar et al.78 similarly reported dark induced anoxia in the massive coral Favia favus. In the microenvironment directly above the coenosarc, O2 diffusion was thought to be primarily responsible for the external [O2]32,77,79. However, high ciliary action has been linked to the heterogeneous distribution of O2 within the CBL and correlated with reductions in oxidative stress32,33.

Overall, these data support the findings of Comeau et al.18,54 that slow flow does not provide refuge from OA, as microchemical extremes are exacerbated in the dark. Cornwall et al.28 argued that low flow environments resulted in daytime pH increases from photosynthesis that ameliorated OA driven pH decreases in marine calcifying macroalgae. However, our data showed that slower flow speeds created extreme microchemical and thick CBLs characterized by low pH and [O2] in dark conditions.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates interspecific differences in proton and O2 flux under elevated pCO2. P. acuta exhibited a coupled response of decreased dark proton efflux and increased light O2 efflux, whereas M. capitata showed no detectable treatment effect. Through deductive reasoning, this study concluded that in P. acuta, dark calcification independent of coral metabolism was diminished under elevated pCO2 via reduced proton efflux from the CBL. Conversely, increased O2 flux under light conditions was likely attributed to increased photosynthetic rates. Simultaneous measurements of pH and O2 within the CBL enable the decoupling of coral metabolism and calcification. Branching, small polyped corals are seldom investigated in direct comparisons, and this is the first study to measure simultaneous proton flux coupled with O2 flux at the ZPC. The microchemical environment of the ZPC supports rapid linear extension and calcification, thus, reduced efflux of calcification inhibitors (protons) could threaten this process. Future studies would benefit from expanding ZPC comparisons, across a broader range of species, and pairing CBL measurements with cf. analyses such as RAMAN spectroscopy.

Methods

Treatment conditions

Six large colonies of M. capitata and P. acuta were collected at approximately 300 m from the shore of the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology in Kāneʻohe Bay, Hawaiʻi. Coral colonies were acclimated to a flow-through seawater mesocosm environment (an area of 1.37 m2 and volume ~ 50 m3) for ten days. Mesocosms received seawater directly from the bay, < 1 km from the collection site, with a residence time of one hour, and were environmentally controlled (e.g., temperature, dissolved oxygen, light, and all carbonate chemistry parameters were naturally adjusted)—exposed to natural light (shaded to 50% ~ PAR 800 µmol m− 2 s− 1 at solar noon). Colonies were halved and tagged via genotype and then acclimated for three days. Directly before placement in treatment conditions, the initial buoyant weight of colonies was recorded (mean Wd control M. capitata: 108 g ± 22; high pCO2: 109 g ± 14; P. acuta control: 252 g ± 28; high pCO2: 177 g ± 46)80. Coral colonies were placed in similar locations in each mesocosm for a 19-day exposure period among other coral colonies (same species) and macrophytes to control spatial acclimation differences due to the mixed flow environment.

Seawater chemistry

All parameters, i.e., temperature (C°), salinity, and nutrients, were not manipulated from the natural seawater (Table 1). Seawater carbonate chemistry was manipulated independently via the bubbling of pure CO2 gas and air mixture directly into mixing pumps in each of the holding mesocosms (Table 1). A pHstat methodology was implemented where pCO2 levels were controlled via the change in seawater pH, and this study aimed for a target ΔpH < 0.3 from control mesocosms, which was achieved through increasing or decreasing bubble rates of CO2 in each mesocosm81. However, the flume environment (Figure S1) collected water from only the control mesocosms, and CO2 was bubbled not directly into the flume but into 1000 mL of seawater until a pH of 4.00 units was achieved, then mixed for one hour with pumps on high until a target quasi-steady-state pH < 0.3. All total alkalinity (AT) measurements were conducted via acid titrations (0.1 M HCl titrant) using a Metrohm Titrino 877 Plus, and all raw AT values were corrected to a certified reference material (CRM) batch #205 (bottled 09/09/2022; Table 1)82. Measurements of temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO mg L− 1), and pHNBS were collected using a YSI ProDDS Multiparameter Digital Water Quality Meter, and subsequent pHNBS values were corrected to a Tris Buffer 41 solution to achieve pHT.

Flume environment

The flume was constructed using cell-cast acrylic formed into two sections, the concentrator (2.09 m2) and the test Sect. (88.9 × 22.3 cm; 1.8 m2; Figure S1). Water flowed into the concentrator via a pump (24 V DC Hygger – 6511 LPH) to a spray bar manifold in the concentrator section. Water was directed to a flow-reducing baffle and exited the concentrator (1250 μm s− 1; τ = 44 min) through a hexagonal flow straightener separating the concentrator and test section. Seawater then exited at the end of the test section through standpipes and gravity-fed into a reservoir below. A 180-w, Wattshine full-spectrum LED aquarium light was affixed above the test section (PAR 800 µmol s− 1), and a micromanipulator arm extended over the test section.

Microsensors and manipulator movements

The O2 microsensor was a PreSens micro-optode (PSt7 – Flat Broken Tip) at a diameter of 230 μm. The pH microsensor is a Unisense microelectrode with a tapered glass tip diameter of 100 μm. The microsensors recorded continuously (1 measurement every 6 s) on respective proprietary programs for the duration of the profile. Sensors were both mounted in a dual-probe auto-micromanipulator (Zaber T-LSR075A) and synced with programming software provided by Zaber. Profiles were conducted where the movement was directed via scripts delivered directly to the auto-micromanipulator, with two separate scripts switched by the user. The sensors were set to pause for 60 s at each height and continue to record continuously with one measurement every six seconds. For the duration the sensor was at a specified height, ten measurements were collected for each parameter and were averaged to characterize each height. The stage was set to travel at 5 μm s− 1 to each specified height, and these processes were repeated until the script finished. From the surface (0 μm), this regime repeated every 100 μm until subsequently reaching a value that reflected the bulk concentration or 2500 μm. Once a height where measurements of O2 and pH reflected the bulk seawater values, the micromanipulator was set to continue an extra 2000 μm at 500 μm intervals to obtain tailing bulk measurements outside of the CBL. All measurements of O2 and pH were standardized to bulk values taken via the external probes on the YSI of the flume seawater at the time of profiling38,83.

Point selection on colonies

Microsensors were positioned according to set parameters that remained constant throughout every profile. O2 sensors were directly beside pH sensors and manually moved as close as possible to the human eye when viewing through a stereoscope. Sensor positioning will follow these criteria in every profile: Locating a ‘tip’ section directly facing into the semi-straight water flow, positioned ‘between polyps,’ and lowering the sensors at micro-scale increments (1–10 μm) until parameters of O2 and pH reach their maximum at a quasi-steady-state (Fig. 11a-d).

CBL thickness

The CBL thickness (δCBL) was calculated by fitting a linear model to the log-transformed concentration profile, expressed as log10([X]) as a function of distance (x) from the coral surface (Eq. 1). Using the fitted intercept (α) and slope (β), we then extrapolated the distance at which the concentration reached the independently measured bulk concentration threshold ([X]bulk) (Eq. 2).

Proton and oxygen flux

Both proton and oxygen flux values were calculated using the H+ and O2 diffusion coefficient, following the methods described in detail in Pacherres et al.33 and replicated from Martins et al.25,31 using the upper linear gradient of complex profiles. Proton flux (JH+) was calculated using Fick’s first law of diffusion, with a linear model applied to the proton concentration (XH+) profile across the distance (x) to determine the concentration gradient (m). The diffusion coefficient for protons (DH+) at a salinity of 35 and a temperature of 26.5 °C (Eq. 3).

Where JH+ is the proton flux, DH+ = 9.31 × 10− 5 cm2 s− 1, and m is the slope (gradient) from the linear model of XH+ as a function of distance.

Oxygen flux (JO2) was determined using Fick’s first law of diffusion. A linear model was applied to the oxygen concentration (XO2) profile across distance to calculate the concentration gradient (m), with the diffusion coefficient for oxygen (DO2) at a salinity of 35 and temperature of 26.5 °C set at 2.20 × 10− 5 cm s− 1 (Eq. 4).

Where JO2 is the oxygen flux, DO2 = 2.20 × 10− 5 cm2 s− 1, and m is the slope (gradient) from the linear model of XO2 as a function of d.

Statistics

To assess the effects of species, treatment, and condition on proton and oxygen flux, we used a series of linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) and linear models (LMs) in R (v4.2.0)84 with the ‘lme4’ and ‘emmeans’ packages. The initial model included all interactions between species, treatment, and condition, along with a random effect for genotype. AIC was used to compare models, and genotype was excluded in several instances due to minimal impact on model fit. The final model, which included all interaction terms without the random effect for genotype, was selected based on the lowest AIC. Residual diagnostics confirmed model assumptions. Post-hoc analyses using estimated marginal means and Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons identified significant differences among treatment, species, and condition combinations. All statistical analyses were conducted at a significance level of α = 0.05 (R Core Team).

Data availability

All raw data and source code used in the analysis are publicly available and found here at https://github.com/CROH-Lab/Proton_and_oxygen_flux_concentration_boundary_layer.git.

References

Caldeira, K. & Wickett, M. E. Anthropogenic carbon and ocean pH. Nature 425, 365–365 (2003).

Kleypas, J. A. et al. Geochemical consequences of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on coral reefs. Science 284, 118–120 (1999).

Sabine, C. L. et al. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Science 305, 367–371 (2004).

Changing & Ocean Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities. in The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)) 447–588Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.007

Fabry, V. J., Seibel, B. A., Feely, R. A. & Orr, J. C. Impacts of ocean acidification on marine fauna and ecosystem processes. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 65, 414–432 (2008).

Gattuso, J. P., Allemand, D. & Frankignoulle, M. Photosynthesis and calcification at Cellular, organismal and community levels in coral reefs: A review on interactions and control by carbonate chemistry. Am. Zool. 39, 160–183 (1999).

Comeau, S., Carpenter, R. C., Lantz, C. A. & Edmunds, P. J. Ocean acidification accelerates dissolution of experimental coral reef communities. Biogeosciences 12, 365–372 (2015).

DeCarlo, T. M. et al. Community production modulates coral reef pH and the sensitivity of ecosystem calcification to ocean acidification. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 122, 745–761 (2017).

Jokiel, P. L., Jury, C. P. & Rodgers, K. S. Coral-algae metabolism and diurnal changes in the CO2-carbonate system of bulk sea water. PeerJ 2, e378 (2014).

Andersson, A. J. & Gledhill, D. Ocean acidification and coral reefs: effects on Breakdown, Dissolution, and net ecosystem calcification. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 5, 321–348 (2013).

Jokiel, P. L. et al. Ocean acidification and calcifying reef organisms: a mesocosm investigation. Coral Reefs. 27, 473–483 (2008).

Bahr, K. D., Jokiel, P. L. & Rodgers, K. S. Relative sensitivity of five Hawaiian coral species to high temperature under high-pCO2 conditions. Coral Reefs. 35, 729–738 (2016).

Bahr, K. D., Jokiel, P. L. & Rodgers, K. S. Seasonal and annual calcification rates of the Hawaiian reef coral, Montipora capitata, under present and future climate change scenarios. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74, 1083–1091 (2017).

Bove, C. B. et al. Common Caribbean corals exhibit highly variable responses to future acidification and warming. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 286, 20182840 (2019).

Comeau, S. et al. Resistance to ocean acidification in coral reef taxa is not gained by acclimatization. Nat. Clim. Change. 9, 477–483 (2019).

Comeau, S., Edmunds, P. J., Spindel, N. B. & Carpenter, R. C. The responses of eight coral reef calcifiers to increasing partial pressure of CO2 do not exhibit a tipping point. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 388–398 (2013).

Bahr, K. D., Rodgers, K. S. & Jokiel, P. L. Ocean warming drives decline in coral metabolism while acidification highlights species-specific responses. Mar. Biol. Res. 14, 924–935 (2018).

Comeau, S. et al. Flow-driven micro-scale pH variability affects the physiology of corals and coralline algae under ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 9, 12829 (2019).

Chan, N. C. S., Wangpraseurt, D., Kühl, M. & Connolly, S. R. Flow and coral morphology control coral surface pH: implications for the effects of ocean acidification. Front Mar. Sci 3, 10 (2016).

Chan, N. C. S. & Connolly, S. R. Sensitivity of coral calcification to ocean acidification: a meta-analysis. Glob Change Biol. 19, 282–290 (2013).

Reynaud, S. et al. Interacting effects of CO2 partial pressure and temperature on photosynthesis and calcification in a scleractinian coral. Glob Change Biol. 9, 1660–1668 (2003).

Langdon, C. & Atkinson, M. J. Effect of elevated pCO2 on photosynthesis and calcification of corals and interactions with seasonal change in temperature/irradiance and nutrient enrichment. J Geophys. Res. Oceans 110, C09S07 (2005).

Jokiel, P. L., Jury, C. P. & Kuffner, I. B. Coral calcification and ocean acidification. In Coral Reefs at the Crossroads Vol. 6 (eds Hubbard, D. K. et al.) 7–45 (Springer Netherlands, 2016).

Kaandorp, J. A., Filatov, M. & Chindapol, N. Simulating and quantifying the environmental influence on coral colony growth and form. In Coral Reefs: an Ecosystem in Transition (eds Dubinsky, Z. & Stambler, N.) 177–185 (Springer Netherlands, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0114-4_11.

Martins, C. P. P., Ziegler, M., Schubert, P., Wilke, T. & Wall, M. Effects of water flow and ocean acidification on oxygen and pH gradients in coral boundary layer. Sci. Rep. 14, 12757 (2024).

Jokiel, P. L. Ocean acidification and control of reef coral calcification by boundary layer limitation of proton flux. Bull. Mar. Sci. 87, 639–657 (2011).

Shashar, N., Kinane, S., Jokiel, P. L. & Patterson, M. R. Hydromechanical boundary layers over a coral reef. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 199, 17–28 (1996).

Cornwall, C. E. et al. Diffusion boundary layers ameliorate the negative effects of ocean acidification on the temperate coralline macroalga arthrocardia corymbosa. PLOS ONE. 9, e97235 (2014).

Crovetto, L., Venn, A. A., Sevilgen, D., Tambutté, S. & Tambutté, E. Spatial variability of and effect of light on the cœlenteron pH of a reef coral. Commun. Biol. 7, 1–10 (2024).

Jimenez, I. M., Kühl, M., Larkum, A. W. D. & Ralph, P. J. Effects of flow and colony morphology on the thermal boundary layer of corals. J. R Soc. Interface. 8, 1785–1795 (2011).

Martins, C. P. P., Wall, M., Schubert, P., Wilke, T. & Ziegler, M. Variability of the surface boundary layer of reef-building coral species. Coral Reefs. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-024-02531-7 (2024).

Pacherres, C. O., Ahmerkamp, S., Koren, K., Richter, C. & Holtappels, M. Ciliary flows in corals ventilate target areas of high photosynthetic oxygen production. Curr. Biol. 32, 4150–4158e3 (2022).

Pacherres, C. O., Ahmerkamp, S., Schmidt-Grieb, G. M., Holtappels, M. & Richter, C. Ciliary vortex flows and oxygen dynamics in the coral boundary layer. Sci. Rep. 10, 7541 (2020).

Henley, E. M. et al. Reproductive plasticity of Hawaiian Montipora corals following thermal stress. Sci. Rep. 11, 12525 (2021).

Saper, J., Høj, L., Humphrey, C. & Bourne, D. G. Quantifying capture and ingestion of live feeds across three coral species. Coral Reefs. 42, 931–943 (2023).

Han, T. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals deep molecular landscapes in stony coral Montipora clade. Front. Genet. 14, 1297483 (2023).

Bhattacharya, D., Stephens, T. G., Tinoco, A. I., Richmond, R. H. & Cleves, P. A. Life on the edge: Hawaiian model for coral evolution. Limnol. Oceanogr. 67, 1976–1985 (2022).

Schoepf, V. et al. Impacts of coral bleaching on pH and oxygen gradients across the coral concentration boundary layer: a microsensor study. Coral Reefs. 37, 1169–1180 (2018).

Gattuso, J. Effect of calcium carbonate saturation of seawater on coral calcification. Glob Planet. Change. 18, 37–46 (1998).

Langdon, C. et al. Effect of calcium carbonate saturation state on the calcification rate of an experimental coral reef. Glob Biogeochem. Cycles. 14, 639–654 (2000).

Jokiel, P. L. The reef coral two compartment proton flux model: A new approach relating tissue-level physiological processes to gross corallum morphology. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 409, 1–12 (2011).

Radice, V. Z., Martinez, A., Paytan, A., Potts, D. C. & Barshis, D. J. Complex dynamics of coral gene expression responses to low pH across species. Mol. Ecol. 33, e17186 (2024).

Yuan, X. et al. Gene expression profiles of two coral species with varied resistance to ocean acidification. Mar. Biotechnol. 21, 151–160 (2019).

Jury, C. P., Whitehead, R. F. & Szmant, A. M. Effects of variations in carbonate chemistry on the calcification rates of Madracis Auretenra (= Madracis mirabilis sensu Wells, 1973): bicarbonate concentrations best predict calcification rates. Glob Change Biol. 16, 1632–1644 (2010).

Bach, L. T. Reconsidering the role of carbonate ion concentration in calcification by marine organisms. Preprint at. https://doi.org/10.5194/bgd-12-6689-2015 (2015).

Hohn, S. & Merico, A. Quantifying the relative importance of transcellular and paracellular ion transports to coral polyp calcification. Front. Earth Sci. 2, 37 (2015).

Venn, A. A., Tambutté, E., Comeau, S. & Tambutté, S. Proton gradients across the coral calcifying cell layer: effects of light, ocean acidification and carbonate chemistry. Front Mar. Sci 9, 973908 (2022).

Venn, A. A., Tambutté, E., Comeau, S. & Tambutté, S. Proton gradients across the coral calcifying cell layer: effects of light, ocean acidification and carbonate chemistry. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 973908 (2022).

Venn, A. A. et al. Impact of seawater acidification on pH at the tissue–skeleton interface and calcification in reef corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 1634–1639 (2013).

Reymond, C. E. & Hohn, S. An experimental approach to assessing the roles of Magnesium, Calcium, and carbonate ratios in marine carbonates. Oceans 2, 193–214 (2021).

Comeau, S., Carpenter, R. C. & Edmunds, P. J. Effects of pCO2 on photosynthesis and respiration of tropical scleractinian corals and calcified algae. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 74, 1092–1102 (2017).

Kaniewska, P. et al. Major cellular and physiological impacts of ocean acidification on a reef Building coral. PLoS ONE. 7, e34659 (2012).

Strahl, J. et al. Physiological and ecological performance differs in four coral taxa at a volcanic carbon dioxide seep. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 184, 179–186 (2015).

Comeau, S., Edmunds, P. J., Lantz, C. A. & Carpenter, R. C. Water flow modulates the response of coral reef communities to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 4, 6681 (2014).

Comeau, S., Cornwall, C. E. & McCulloch, M. T. Decoupling between the response of coral calcifying fluid pH and calcification to ocean acidification. Sci. Rep. 7, 7573 (2017).

Cornwall, C. E. et al. Resistance of corals and coralline algae to ocean acidification: physiological control of calcification under natural pH variability. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20181168 (2018).

Comeau, S., Cornwall, C. E., DeCarlo, T. M., Krieger, E. & McCulloch, M. T. Similar controls on calcification under ocean acidification across unrelated coral reef taxa. Glob Change Biol. 24, 4857–4868 (2018).

Allemand, D. et al. Biomineralisation in reef-building corals: from molecular mechanisms to environmental control. C.R. Palevol. 3, 453–467 (2004).

McConnaughey, T. A. & Whelan, J. F. Calcification generates protons for nutrient and bicarbonate uptake. Earth-Sci. Rev. 42, 95–117 (1997).

Bertucci, A. et al. Carbonic anhydrases in anthozoan corals—A review. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 1437–1450 (2013).

Allemand, D., Tambutté, É., Zoccola, D. & Tambutté, S. Coral Calcification, cells to reefs. In Coral Reefs: an Ecosystem in Transition (eds Dubinsky, Z. & Stambler, N.) 119–150 (Springer Netherlands, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0114-4_9.

Furla, P., Galgani, I., Durand, I. & Allemand, D. Sources and mechanisms of inorganic carbon transport for coral calcification and photosynthesis. J. Exp. Biol. 203, 3445–3457 (2000).

Allemand, D., Furla, P. & Bénazet-Tambutté, S. Mechanisms of carbon acquisition for endosymbiont photosynthesis in anthozoa. Can. J. Bot. 76, 925–941 (1998).

Cameron, L. P. et al. Impacts of warming and acidification on coral calcification linked to photosymbiont loss and deregulation of calcifying fluid pH. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 1106 (2022).

Barott, K. L, Venn, A. A, Perez, S. O., TambuttéS S. & Tresguerres M. Coral host cells acidify symbiotic algal microenvironment to promote photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 607–612 (2015).

Rivest, E. B., Comeau, S. & Cornwall, C. E. The role of natural variability in shaping the response of coral reef organisms to climate change. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 3, 271–281 (2017).

Shaw, E. C., McNeil, B. I., Tilbrook, B., Matear, R. & Bates, M. L. Anthropogenic changes to seawater buffer capacity combined with natural reef metabolism induce extreme future coral reef CO2 conditions. Glob Change Biol. 19, 1632–1641 (2013).

Enochs, I. C. et al. The influence of diel carbonate chemistry fluctuations on the calcification rate of Acropora cervicornis under present day and future acidification conditions. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 506, 135–143 (2018).

Jokiel, P. L. & Coles, S. L. Response of Hawaiian and other Indo-Pacific reef corals to elevated temperature. Coral Reefs. 8, 155–162 (1990).

Shamberger, K. E. F. et al. Diverse coral communities in naturally acidified waters of a Western Pacific reef. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 499–504 (2014).

Comeau, S., Edmunds, P. J., Spindel, N. B. & Carpenter, R. C. Diel pCO2 oscillations modulate the response of the coral acropora hyacinthus to ocean acidification. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 501, 99–111 (2014).

Kealoha, A. K. et al. Heterotrophy of oceanic particulate organic matter elevates net ecosystem calcification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 9851–9860 (2019).

Bahr, K. D., Jokiel, P. L. & Toonen, R. J. The unnatural history of Kāne‘ohe bay: coral reef resilience in the face of centuries of anthropogenic impacts. PeerJ 3, e950 (2015).

Schmidt-Roach, S., Miller, K. J., Lundgren, P. & Andreakis, N. With eyes wide open: a revision of species within and closely related to the ocillopora damicornis species complex (Scleractinia; Pocilloporidae) using morphology and genetics. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 170, 1–33 (2014).

Yost, D. M. et al. Diversity in skeletal architecture influences biological heterogeneity and Symbiodinium habitat in corals. Zoology 116, 262–269 (2013).

Cohen, A. L., McCorkle, D. C., de Putron, S., Gaetani, G. A. & Rose, K. A. Morphological and compositional changes in the skeletons of new coral recruits reared in acidified seawater: insights into the biomineralization response to ocean acidification. Geochem Geophys. Geosystems 10, Q07005 (2009).

Shapiro, O. et al. Vortical ciliary flows actively enhance mass transport in reef corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, (2014).

Shashar, N., Cohen, Y. & Loya, Y. Extreme diel fluctuations of oxygen in diffusive boundary layers surrounding stony corals. Biol. Bull. 185, 455–461 (1993).

Kühl, M., Cohen, Y., Dalsgaard, T., Jørgensen, B. B. & Revsbech, N. P. Microenvironment and photosynthesis of zooxanthellae in scleractinian corals studied with microsensors for O₂, pH and light. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 117, 159–172 (1995).

Jokiel, P. Coral growth: buoyant weight technique. Coral Reefs: Research Methods 529–541 (1978).

Jokiel, P. L., Bahr, K. D. & Rodgers, K. S. Low-cost, high-flow mesocosm system for simulating ocean acidification with CO2 gas. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods. 12, 313–322 (2014).

Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements (North Pacific Marine Science Organization, 2007).

Hurd, C. L. & Pilditch, C. A. Flow-Induced morphological variations affect diffusion Boundary-Layer thickness of macrocystis pyrifera (heterokontophyta, Laminariales)1. J. Phycol. 47, 341–351 (2011).

R Core Team. The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/

Acknowledgements

All corals in this study were collected under special activities permit (SAP) 2022-2023. This work was conducted at the Coral Reef Ecology Lab under Dr. Ku‘ulei Rodgers, located at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology, a place that has long been home to pioneering research in coral reef ecology. We stand on the shoulders of the many scientists whose foundational work in this lab has shaped our understanding of coral reefs, and we are especially grateful for the mentorship, resources, and knowledge that continue to be shared so generously by this community. Also, those associated with this work respect and recognize the connection shared between the Hawaiian culture with coral reefs surrounding the islands, and hope that findings here contribute to the preservation of these ecosystems in malama ʻāina for those who depend on them. We would also like to thank Tim Woolston and Raj Shingadia, at My Reef Creations® for custom design and development of the flume aquaria that made this study possible.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation award #OCE-2049406.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author David A. Armstrong conducted experiments, data analysis, writing, interpretation, and figure design. Author Conall McNicholl assisted in the experimental design, data collection, intellectual guidance, and manuscript editing. Author Keisha D. Bahr assisted in experimental design, funding acquisition, and manuscript editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Armstrong, D.A., McNicholl, C. & Bahr, K.D. Ocean acidification modulates material flux linked with coral calcification and photosynthesis. Sci Rep 16, 1255 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30818-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30818-4