Abstract

External Floating Roof Tanks (EFRTs) are prone to fire and explosion due to the convergence of human error, technical failure, and weak emergency response. Existing models often use ranking-based methods that fail to reflect systemic interdependencies. This study aimed to develop and validate a structural model that explains the latent constructs underlying EFRT hazards using a theory-informed, data-driven approach. A structured checklist with 71 indicators across 11 domains was developed through expert input and literature review. Data from 285 professionals were analysed using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to identify key dimensions, followed by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and path analysis for model validation. EFA extracted 11 factors explaining 72% of the total variance. CFA showed strong fit indices (CFI = 0.915, RMSEA = 0.048). Path analysis confirmed significant causal relationships, including those from operational error to technical failure and fire suppression breakdown. A real-world case study involving 11 EFRTs demonstrated that model-predicted high-risk tanks aligned closely with expert evaluations. The final model provides a multidimensional and statistically validated framework for understanding EFRT risks, integrating human, technical, and organizational domains. This model offers practical guidance for safety engineers to identify high-leverage intervention points. It supports the development of predictive safety tools and can be adapted for integration into intelligent fire prevention systems across storage infrastructures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Petroleum storage facilities represent one of the most critical components of the global energy infrastructure, providing large-scale containment for highly flammable hydrocarbon products such as crude oil, gasoline, and liquefied petroleum gas1 (Fig. 1). Among various storage technologies, external floating roof tanks (EFRTs) (Fig. 2)2 are widely adopted for their ability to minimize vapor losses and reduce emissions. These tanks feature a floating roof that adjusts with liquid levels, thereby decreasing the space available for flammable vapours to accumulate3. However, despite these advantages, EFRTs are inherently prone to fire and explosion risks, particularly in the presence of operational malfunctions, environmental stimuli, and external triggers such as lightning4,5.

Statistical records and post-accident investigations confirm that EFRTs have been involved in numerous catastrophic incidents over the past decades6. The floating roof structure, although functionally efficient, introduces vulnerabilities such as seal failures, rainwater accumulation, static charge build-up, and vapor leakage that significantly contribute to ignition risks7. Boilover phenomena, vapor cloud formation, and structural collapse under pressure are some of the severe consequences observed in these tanks2.These events not only lead to operational shutdowns and economic loss but also pose threats to nearby communities, ecosystems, and emergency responders8.

To mitigate these risks, engineers and safety professionals require accurate and validated tools for hazard identification, risk prioritization, and incident prediction. Traditional risk assessment approaches such as HAZOP (Hazard and Operability Studies)9, Fault Tree Analysis (FTA)10, and Fire and Explosion Index (F&EI)11 have long served as foundational methods. However, as risk profiles in industrial contexts grow more complex, there is a need for advanced, data-driven, and statistically valid models that can reflect the interactions and weightings among diverse risk factors.

To systematically understand and manage these complex hazards, recent studies have increasingly adopted multivariate statistical methods12 to explore latent structures and confirm theoretical models. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)13 is often used as a data-driven technique to identify the underlying dimensions of risk factors without prior assumptions. In contrast, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)14 tests whether a hypothesized factor structure fits observed data, providing statistical evidence of model validity and reliability. Together, these tools offer a rigorous pathway for developing and validating robust fire and explosion risk assessment frameworks.

Numerous studies have focused on modelling and quantifying the risks associated with fire and explosion in the oil and gas sector. For example, Zhang et al. (2016)10 utilized an improved AHP-FTA hybrid method to prioritize risk causes in steel oil tanks. Their model integrated fault tree logic with expert-based weighting to identify key accident paths. Similarly, Jia et al. (2024)15 modified the Analytic Hierarchy Process to suit EFRT scenarios, producing a refined model for evaluating fire and explosion events. These efforts marked significant progress in incorporating expert judgment and system logic into risk analysis.

Moshashaei et al. (2017, 2018)6,16 contributed a literature review and prioritization framework tailored to EFRTs, identifying both natural and human-induced ignition sources such as lightning, static electricity, and operational negligence. These studies emphasized the uniqueness of EFRT fire dynamics, reinforcing the need for risk models that account for tank-specific variables. Sarvestani et al. (2021)17 and Attia & Sinha (2021)18 explored predictive models for LPG and propane tank hazards, while He et al. (2020)19 developed a detection response model for liquid leakage in flammable tanks.

The integration of fuzzy logic and Bayesian networks has also enriched risk modelling. For example, Li et al. (2019)20 applied fuzzy Bayesian methods to model mine ignition sources, and Cheng & Luo (2021)21 adopted Bayesian networks to quantify Natech risks (natural hazard-triggered technological accidents) in floating roof tanks. These approaches enable probabilistic reasoning but often lack interpretability and structural validation.

As complexity increases, some researchers have turned toward multivariate statistical modelling to uncover latent dimensions and causal links among risk variables. For instance, Soltanzadeh et al. (2022)22 and Upadhyaya & Malek (2024)23 used EFA to categorize safety indicators and extract underlying risk dimensions in chemical and construction industries. Mohammadfam et al. (2017)24 and Rahlina et al. (2019)25 employed CFA to validate their proposed models in occupational settings.

Beyond individual latent factors, researchers like Gerassis et al. (2019)26 and Jiang et al. (2025)27 used Path Analysis and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to visualize and test causal pathways in complex accident scenarios. These models allow for simultaneous testing of direct and indirect relationships among risk contributors, offering a more complete understanding of system behaviour. However, most of these applications are generic and not tailored to the specific structure and failure modes of EFRTs.

Although various methods have been proposed for fire and explosion risk assessment, most existing models fall short in capturing the complex interdependencies among risk factors, particularly in EFRTs. Techniques like AHP and FTA are largely linear, while studies using EFA, and CFA rarely apply them sequentially. Path analysis, which could reveal causal linkages between risk dimensions, is also underutilized, especially for EFRT-specific issues like seal failure or vapor leakage. Moreover, empirical validation through real-world case studies is often lacking, limiting practical relevance.

Given the limitations of prior research and the need for a comprehensive, theory-informed framework, this study aims to develop and validate an integrated structural model for fire and explosion risk assessment in EFRTs. To this end, a total of 89 risk factors were initially identified through expert consultation. The model employs EFA for dimensionality reduction, CFA for construct validation, and path analysis to reveal the causal relationships among latent variables. Grounded in Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model and tested on real-world data from petroleum storage facilities, the proposed framework offers both theoretical advancement and a practical decision-support tool for industrial safety management. Specifically, this study contributes to the research community by presenting an empirically validated, data-driven causal framework that unifies exploratory, confirmatory, and causal modelling approaches within a single analytical sequence. From an industrial perspective, the framework provides a systematic and evidence-based mechanism for identifying, prioritizing, and mitigating fire and explosion risks in EFRT operations, thereby bridging the gap between academic research and practical safety management.

Theoretical framework

Fire and explosion hazards in petroleum storage environments are rarely the result of a single, isolated failure. Rather, they emerge from the interdependent interplay of technical, operational, and environmental risk factors, many of which are latent, multifaceted, and difficult to observe directly. The conceptual framework of this study (Fig. 3) is grounded in Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model of accident causation28, which posits that major incidents often result from the alignment of multiple system-level deficiencies rather than a single point of failure. The model distinguishes between latent conditions29, such as inadequate maintenance protocols, flawed equipment design, or insufficient safety barriers, and active failures30, including human errors, procedural violations, or misjudgements at the operational level. These layers of vulnerability can align, like holes in slices of Swiss cheese, to breach defences and trigger catastrophic outcomes. This theoretical lens provides a strong foundation for the multifactorial structure investigated in the current study, wherein technical failures, operational errors, sabotage, emergency response limitations, and design inadequacies are conceptualized as interrelated contributors to fire and explosion risk in EFRTs. Incorporating this framework enhances the explanatory depth of the model and lends theoretical legitimacy to the interconnected network of causality assessed through EFA, CFA, and path analysis. To rigorously examine such a system, this study adopts an integrated theoretical framework grounded in four core foundations: systems theory, latent variable modelling, multidimensional risk theory, and causal attribution.

Systems theory in safety engineering

This study adopts a systems theory perspective, which views accidents not as isolated failures but as outcomes of complex interactions among human, technical, and environmental components within a sociotechnical system. In the case of EFRTs, events such as seal failure, vapor accumulation, lightning strikes, and operational errors often act together, forming a dynamic network of interrelated risks15,16.

Traditional tools like HAZOP or FTA typically model risks linearly and struggle to capture feedback loops or multi-causal pathways10,31. However, as Feng et al. (2022)32 and Saloua et al. (2019)33 note, serious industrial accidents often arise from systemic weaknesses across organizational, procedural, and equipment levels.

Grounded in a systems-based perspective, the current study employs multivariate statistical models such as EFA, CFA, and path analysis to explore and validate the latent structures underlying fire and explosion risks. This analytical strategy allows for the identification of both individual hazard factors and the causal mechanisms through which these risks interact and intensify. The result is a more comprehensive and integrated foundation for modelling safety risks in external floating roof tanks.

Latent variable modelling paradigm

In the context of fire and explosion risk assessment, particularly within complex systems such as EFRTs, many of the most critical risk contributors are not directly observable. Factors like maintenance quality, organizational safety culture, emergency response readiness, and susceptibility to environmental hazards often operate as latent variables, that is, underlying constructs inferred from patterns among measurable indicators22,34. Relying solely on surface-level observations such as checklists or incident logs risks oversimplifying the multidimensional nature of risk. To address this challenge, the current study adopts a latent variable modelling paradigm, which treats observable variables as proxies for deeper constructs that must be statistically extracted and validated.

To operationalize this paradigm, the study employs a two-phase analytic process involving both EFA and CFA. EFA is first applied to uncover the underlying structure of the dataset without imposing any predefined theoretical model, allowing data-driven insights to emerge23,35. This is especially useful in domains like process safety, where interrelations between human, technical, and organizational risks are complex and context dependent. Following this, CFA is used to formally test the validity and reliability of the factor structure suggested by EFA, ensuring that the model is statistically sound and fits the observed data24,25. The combination of EFA and CFA strengthens the construct validity of the model and allows for more precise path analysis in subsequent modelling stages. This paradigm thus serves as a robust foundation for identifying high-risk dimensions, assessing their measurement properties, and ultimately enabling more effective risk prediction and intervention design in EFRT environments.

Multidimensional risk theory

This framework is further grounded in multidimensional risk theory, which views risk not as a single variable or linear outcome, but as the result of multiple, overlapping, and interacting dimensions. These include technical factors, operational factors, human factors, and environmental conditions17,36. In EFRT systems, these dimensions do not act independently; instead, they interact dynamically, often in nonlinear ways. For example, poor procedural compliance may not pose immediate danger, but when coupled with extreme weather or aging infrastructure, the risk of fire or explosion can escalate rapidly16,37.

Such a perspective aligns closely with the factor-analytic modelling approach used in this study. Multidimensional risk theory supports the identification of latent structures by grouping statistically correlated indicators into distinct yet interconnected constructs. These constructs represent higher-order dimensions of risk that can be analysed for both their individual contribution and cumulative influence on overall system safety10,38. This theoretical lens allows for more realistic modelling of EFRT risks by acknowledging that incidents rarely stem from a single point of failure, but instead emerge from the convergence and interaction of various contributing factors. It also enhances the interpretability of path analysis results by making explicit the interdependencies among different domains of risk, thereby improving the practical value of the model for safety engineering and operational decision-making.

Causal attribution and path modelling

In high-risk systems such as petroleum storage tanks, particularly EFRTs, understanding the presence of risk factors is not enough, what matters equally is how these factors interact and escalate into actual incidents. To address this dimension, the present framework draws on causal attribution theory, which posits that individuals and systems interpret hazardous events through identifiable cause-and-effect chains. In the field of industrial safety, this theory underpins analytical strategies that go beyond identifying isolated variables and instead focus on how those variables dynamically influence one another, often under specific operational or environmental conditions27,33.

To operationalize this perspective, the study utilizes path analysis, a statistical technique well-suited for modelling the directional relationships between latent constructs that have already been identified and validated via EFA and CFA. Path analysis enables the decomposition of total effects into direct and indirect influences, providing deeper insight into how factors such as “maintenance error,” “natural hazards,” or “fire suppression system reliability” contribute to risk escalation26,38. For example, Moshashaei et al. (2018)16 emphasized the indirect role of environmental conditions such as lightning, or heavy rainfall in worsening the outcomes of latent equipment failures in EFRTs. Additionally, Jiang et al. (2025)27 demonstrated how causal modelling can uncover critical propagation paths between design vulnerabilities and operational failure points in chemical storage tanks. Identifying statistically significant pathways allows the model developed in this study to reveal key leverage points within the system, critical nodes where targeted interventions are most likely to prevent the escalation of risk. This integration of theory-driven modelling and empirical causal mapping establishes a strong foundation for predictive safety analysis and informed decision-making in the petrochemical storage sector.

Synthesis of framework

To address these methodological gaps, the present study introduces a unified four-pronged analytical framework that sequentially integrates a structured checklist, Exploratory Factor Analysis EFA, CFA, and Path Analysis. This approach represents a methodological advancement over prior EFRT risk models, which typically relied on hierarchical or judgment-based techniques such as AHP or FTA without statistically validating latent structures. By combining exploratory and confirmatory analyses within a single causal modelling sequence, the framework enables both empirical dimensionality reduction and theory-driven causal inference. Moreover, the inclusion of a structured checklist at the data-collection stage ensures that the subsequent factor analyses are grounded in systematically defined and context-specific indicators, thereby enhancing the model’s validity and reproducibility. This framework conceptualizes fire and explosion risks in EFRTs as outcomes of a multidimensional and latent system of interrelated factors. It uses EFA to uncover hidden structures, CFA to validate their reliability, and path analysis to map causal relationships. The model’s real-world applicability is confirmed through case-based validation. Together, these components provide both a rigorous analytical foundation and a practical tool for risk assessment and mitigation in oil storage operations, supporting informed decision-making and proactive hazard management.

The integrated framework proposed in this study represents a unique synthesis of data-driven and theory-based modelling approaches. By employing EFA and CFA, the model extracts and validates latent risk dimensions empirically from expert-assessed data, ensuring that the underlying constructs are statistically grounded rather than subjectively imposed. Subsequently, path analysis transforms these validated dimensions into a causal network that reveals both direct and indirect interrelations among risk factors. This sequential integration enables a rare balance between empirical dimensionality reduction and theoretical causal validation—a methodological combination seldom applied in EFRT safety research. As a result, the model not only quantifies relationships among complex technical, human, and environmental factors but also provides an evidence-based mechanism for explaining how these factors collectively shape the likelihood and severity of fire and explosion incidents.

Methods

Structural modelling and algorithm development

To construct a robust structural model capturing the causal relationships among key risk factors associated with fire and explosion events in EFRTs, a detailed quantitative checklist was developed. This instrument was based on an empirically refined list of 80 risk indicators, classified under 11 primary constructs and 69 subdimensions derived from expert input and literature synthesis. These indicators represented multidimensional risk categories spanning technical, human, organizational, and environmental domains.

Each item was evaluated using a 10-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “very low impact” and 10 representing “very high impact.” The decision to use a 10-point scale was made to allow for greater response sensitivity and discrimination among risk factors. A broader scale provides respondents with a more nuanced range of options to express their judgment, especially in a context where perceived risk intensity may vary subtly but significantly. This approach also enhances the robustness of statistical analysis by increasing score variance and improving factor extraction performance.

The checklist was disseminated among a purposive sample of domain experts, including process safety engineers, fire protection specialists, and HSE managers with at least ten years of experience in petroleum storage operations. Experts were selected from high-risk industrial environments such as oil terminals, refineries, and petrochemical depots. Participants were selected using purposive sampling, targeting professionals with direct experience in the operation, inspection, or maintenance of EFRTs. This approach ensured that respondents possessed relevant technical knowledge and practical insight required for evaluating fire and explosion risk indicators.

The final sample encompassed a diverse range of participants from three primary sectors: petrochemical (34.3%), oil refining (33.8%), and storage operations (31.9%). Job roles included operations staff (36.2%), safety officers (32.9%), and maintenance engineers (30.9%), reflecting a balanced cross-section of professional responsibilities within EFRT environments. In terms of experience, 25.2% had less than five years of industry tenure, 40.0% had between five and ten years, and 34.8% had more than ten years of experience. Educational backgrounds varied, with 20.5% holding diplomas, 49.5% bachelor’s degrees, and 30.0% postgraduate qualifications (MSc or above). Additionally, 71.9% of participants were based in onshore terminals, while 28.1% worked in offshore settings. This distribution of professional and contextual characteristics strengthens the external validity of the findings and suggests that the data reflect a representative operational reality across different EFRT-related contexts.

In addition to quantitative ratings, participants were encouraged to provide brief qualitative comments to justify any items they rated particularly very high or very low. These written justifications were content analysed to extract recurring rationales and operational contexts. This qualitative layer served two purposes: (1) validating the relevance and clarity of questionnaire items, and (2) enriching the interpretation of outlier scores by contextualizing expert judgments. Where inconsistencies emerged across respondents, the qualitative feedback enabled the research team to distinguish between statistical anomalies and meaningful expert divergence. This integration of quantitative scoring with expert narrative insight added depth and credibility to the data used for the subsequent EFA–CFA modelling process.

Reliability analysis

To evaluate the internal consistency of the measurement model, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was computed for each latent construct using IBM SPSS Statistics v24. Cronbach’s alpha39 is a widely recognized metric in psychometric analysis that reflects the degree of interrelatedness among a set of items intended to measure the same underlying factor. High internal consistency indicates that the items within a construct reliably assess the same conceptual domain40.

In this study, a threshold of α ≥ 0.70 was used to indicate acceptable reliability, in line with established recommendations in behavioural and safety sciences. However, constructs with alpha values between 0.60 and 0.69 were also retained when supported by theoretical justification or domain-specific relevance. This flexibility allowed the inclusion of constructs that, despite marginal alpha values, were conceptually important in EFRT risk modelling and supported by expert judgment.

Conducting this reliability check was essential before proceeding to factor analyses, as it confirmed that the observed items within each proposed dimension formed a coherent and interpretable set, suitable for latent structure validation in the subsequent EFA and CFA procedures. Additionally, descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis were examined to assess the distributional characteristics of items before modelling.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

To explore the underlying structure of the observed risk indicators without imposing any predefined theoretical framework, EFA was conducted. This statistical method is particularly useful in the early stages of model development where the dimensionality of the data is unknown or uncertain41. EFA allows for the empirical discovery of latent constructs by identifying patterns of correlations among measured variables and grouping them into factors that represent common underlying sources of variance42.

Prior to conducting EFA, the adequacy of the data was assessed using two diagnostic tests. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was used to determine whether the partial correlations among items were sufficiently small, indicating that factor analysis would yield reliable dimensions. In this study, KMO values above 0.80 confirmed the suitability of the data for factor extraction. In addition, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was performed to examine whether the correlation matrix significantly differed from an identity matrix. A significant result (p < 0.05) indicated that the variables were intercorrelated enough to justify factor analysis.

Factor extraction was carried out using the Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) method, which is preferred when the goal is to identify latent variables rather than maximize total variance explained (as in PCA). To improve the clarity and interpretability of the results, varimax orthogonal rotation was applied. This rotation technique simplifies factor loadings by maximizing the variance of squared loadings across factors, making it easier to identify which variables belong to which latent construct.

Items with factor loadings below 0.40 were removed to ensure strong associations between variables and their respective factors. Additionally, variables exhibiting cross-loadings above 0.30 on multiple factors were excluded to maintain discriminant validity between constructs.

The EFA served several critical purposes within the modelling framework. First, it allowed for dimensionality reduction, streamlining the 80 risk indicators into a more manageable and interpretable structure. Second, it revealed coherent clusters of related risk factors each potentially representing a distinct risk dimension. Third, the identified factors formed the initial basis for the measurement model used in CFA, supporting both the construct validity and parsimony of the final structural model.

Ultimately, EFA helped ensure that the structural model was not only statistically sound but also conceptually grounded in how experts perceive and prioritize risk in external floating roof tank (EFRT) operations.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Following the exploratory phase, CFA was conducted to statistically test the validity of the latent structure derived from EFA and to determine whether the proposed measurement model provided an adequate fit to the observed data. Unlike EFA, which is exploratory in nature, CFA is a theory-driven approach that allows researchers to specify which variables are expected to load on which latent constructs43. This method helps verify how well the data conform to the theoretical expectations established during the conceptual modelling phase44.

CFA was performed using AMOS software45, employing the maximum likelihood (ML)46 estimation method, which is widely used due to its efficiency and robustness, especially when the data approximate a normal distribution and the sample size is adequate. The input for the model was the variance–covariance matrix of the observed variables, reflecting the degree of shared variance among indicators.

In addition to global fit indices, construct reliability and statistical significance of parameter estimates were examined. Each factor loading was tested using T-values (critical ratios), with thresholds of |t| > 1.96 (p < 0.05) and |t| > 2.58 (p < 0.01) used to establish statistical significance. This step was essential for confirming that the observed variables were meaningfully and significantly related to their respective latent constructs.

The application of CFA played a critical role in validating the measurement model, ensuring it was both theoretically justified and statistically sound. The validated model then provided a solid foundation for subsequent structural modelling and path analysis, enabling the investigation of causal relationships among risk dimensions in a reliable and interpretable manner.

Path analysis and conceptual model evaluation

To investigate the directional and causal relationships among the validated latent constructs derived from CFA47, a path analysis was performed. Path analysis serves as a specialized form of SEM that allows researchers to test the magnitude and direction of hypothesized causal effects between variables48. Unlike CFA, which focuses on the measurement model, path analysis evaluates the structural model, mapping how constructs interact to influence system behaviour49.

In this study, the input data for path analysis consisted of a correlation matrix based on the observed Likert-scale responses. Given the ordinal nature of the data, the Weighted Least Squares (WLS) estimation method was used, which is well-suited for handling non-continuous variables and provides more robust parameter estimates than traditional maximum likelihood in such contexts.

The proposed path model included hypothesized relationships among several core constructs such as operational error, system reliability, external hazards, equipment vulnerability, and emergency response capacity. These pathways were informed by both empirical findings from EFA–CFA and conceptual insights grounded in safety engineering literature. The model sought to uncover direct and indirect influences, for example, how system reliability might moderate the impact of external hazards, or how structural design flaws could indirectly increase risk severity through their influence on emergency system performance.

Model adequacy was evaluated using the same set of fit indices applied during CFA, ensuring consistency in assessing both measurement and structural validity. Additionally, standardized regression weights (β coefficients) and T-values were examined to determine the strength and statistical significance of each path. Only paths with theoretical justification and statistically significant coefficients (typically p < 0.05) were retained in the final model.

Collectively, the validated model served both diagnostic and predictive purposes, providing safety professionals with a practical and evidence-based tool for prioritizing risk control strategies and mitigating cascading failures in complex industrial storage systems.

Severity index and risk classification

Following the completion of structural and path modelling, a Severity Index (S) was computed for each validated risk factor to quantify the potential magnitude of its consequences in the event of an incident. The severity scores were derived by integrating expert evaluations regarding the expected outcomes of each risk item using a consistent and structured scoring rubric.

To classify the overall level of risk, the Severity Index (S) was combined with a Probability Score (P), which reflected the perceived likelihood of occurrence as judged by the same panel of domain experts. These two dimensions were plotted on a standard risk matrix, yielding a composite risk score for each item and enabling its categorization into four primary zones: low, moderate, high, and intolerable risk.

This classification framework served several important purposes. First, it allowed the prioritization of risk factors based on both their impact and likelihood, ensuring that decision-makers could focus attention and resources on high-severity, high-probability threats. Second, it facilitated the identification of intolerable risks and distinguished them from acceptable risks, which could be managed under existing controls. Finally, it provided a transparent and reproducible mechanism for aligning expert judgment with risk governance protocols commonly used in the oil and gas industry.

The combination of quantitative modelling and expert-driven classification ensured that the proposed EFRT risk framework was not only analytically robust but also practically actionable, bridging the gap between statistical outputs and real-world safety interventions.

Method validation through case studies

To verify the accuracy and practical utility of the proposed risk model, four case-based validation strategies were implemented. First, the model was applied to EFRTs with no recorded incidents, and the resulting risk scores were reviewed in expert panels to assess alignment with expected risk levels under normal operations. Second, model outputs were benchmarked against previous risk assessments to evaluate consistency and compatibility.

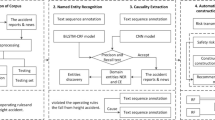

Third, a retrospective analysis was conducted on tanks that had experienced known fire or explosion incidents. The model’s ability to assign high-risk scores in these cases served as a test of its diagnostic validity. Finally, the inter-rater reliability of expert inputs was evaluated by comparing responses from 3 to 4 independent assessors using mean scores, standard deviations, and the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). Together, these validation strategies confirmed the model’s credibility and applicability across different operational scenarios. A visual summary of the research methodology, from instrument design to case-based validation, is presented in Fig. 4.

Results

Internal consistency and reliability analysis

To evaluate the internal consistency of the measurement tool designed for identifying latent fire and explosion risk factors in EFRTs, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were computed for all 11 primary risk dimensions. As shown in Table 1, the alpha values ranged from 0.60 to 0.82, indicating acceptable to high reliability across the constructs. The dimension “Uncontrolled Exothermic Reactions” exhibited the highest internal consistency (α = 0.82), while “Maintenance Errors” and “Faulty Fire Suppression Systems” presented the lowest reliability scores (α = 0.60). Despite the lower values, these two constructs were retained due to their theoretical and operational relevance in the context of process safety.

To improve overall model reliability, three items, ME6, FF4, and FF5, were excluded due to their weak inter-item correlations and poor factor contributions, as identified in the exploratory factor analysis phase. These refinements helped ensure that the latent constructs used in subsequent CFA and path analysis possessed adequate scale coherence.

Sampling adequacy and EFA assumptions

To evaluate the suitability of the dataset for Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), two diagnostic tests were conducted: the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. The KMO statistic, which assesses the proportion of variance among variables that might be common variance, was calculated to be 0.618. Although this value is considered moderate (typically values ≥ 0.6 are acceptable), it nonetheless indicates an adequate level of shared variance for factor extraction.

In addition, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded a highly significant result (χ² = 7238.63, df = 3321, p < 0.001), confirming that the observed correlation matrix was not an identity matrix and thus appropriate for structure detection via EFA (Table 2). Together, these metrics validated the assumption that the data matrix contained sufficient inter-item correlations to justify the use of factor analytic techniques.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

To empirically uncover the latent dimensions of fire and explosion risk in EFRTs, an EFA was conducted using Principal Axis Factoring with Varimax Rotation. Prior to extraction, missing responses in the dataset were handled using the mean imputation method, ensuring a complete matrix for analysis.

The Scree Plot (Fig. 5) guided the initial determination of factor retention. A clear inflection point was observed after the 12th component, indicating that 12 factors could account for meaningful variance in the dataset. However, after evaluating theoretical coherence and statistical parsimony, an 11-factor model was selected. This solution aligned better with existing literature and provided more interpretable constructs related to operational, technical, environmental, and organizational risks.

Three items, ME6, FF4, and FF5, were excluded during the analysis due to low communalities (less than 0.20), weak factor loadings, and theoretical redundancy. This step ensured that only robust and meaningful indicators were retained for subsequent confirmatory analysis. In addition to ME6, FF4, and FF5, several theoretically important but statistically weak indicators, such as ‘lack of coordination with urban firefighting services’ and ‘insufficient foam and powder agents’, were excluded due to low communalities (< 0.20) or unstable factor loadings. These decisions were based solely on quantitative criteria, though their practical relevance remains significant.

The communalities of retained items are shown in Table 3, confirming adequate shared variance across most items. All included indicators surpassed the minimum communality threshold of 0.25, indicating that the extracted factors successfully represented a substantial portion of item variances. The total variance explained by the final 11-factor model was 72% (see Table 4), which is considered satisfactory for behavioural and safety-related studies involving complex, multidimensional constructs.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

To validate the factorial structure derived from the exploratory phase, a CFA was conducted using AMOS software. Both the 11-factor and 12-factor models were tested to determine which structure offered superior statistical and conceptual fit. Although the two models yielded comparable values across several fit indices, the 11-factor solution was ultimately retained due to its stronger alignment with theoretical constructs and better parsimony.

The model evaluation was based on multiple goodness-of-fit indices. As shown in Table 5, the chi-square p-values for both models were highly significant, which is expected given the large sample size. The RMSEA for the 11-factor model was 0.048, well below the acceptable threshold of 0.08, indicating a good fit. Similarly, the RMR (0.181) and GFI (0.693) supported the model’s adequacy. However, other indices such as CFI (0.552), NFI (0.341), and TLI (0.533) fell short of the conventional cut-off of 0.90, suggesting room for structural refinement.

The initial measurement model indicated potential misspecifications, including low-loading indicators, redundant error covariances, and several non-significant structural paths. In response, the model was iteratively refined based on modification indices and theoretical coherence. First, five weak or cross-loading indicators (ME6, FF4, FF5, OE5, and SE12) were removed to improve measurement clarity. Next, theoretically justifiable covariances were introduced between conceptually related constructs, such as Operational Error and Technical Failure, and Operational Error and Safety Response, to account for shared unexplained variance. Finally, structurally non-significant paths (p > 0.05) were trimmed to increase parsimony. After each adjustment, the model was re-estimated, and convergence was reached after three iterations. The final revised model demonstrated substantially improved fit indices (CFI = 0.915; TLI = 0.918; RMSEA = 0.036; χ²/df = 2.02), confirming the structural soundness and theoretical validity of the optimized 11-factor solution.

Model refinement and path specification

Following the initial confirmatory analysis, model refinement procedures were employed to improve fit quality, reduce complexity, and ensure theoretical alignment. Structural adjustments were guided by empirical evidence derived from regression weights and covariance relationships among constructs. Non-significant paths that lacked statistical support were eliminated to enhance model parsimony. Simultaneously, new covariance relationships were introduced between conceptually related domains such as OE ↔ TE and OE ↔ S, based on modification indices and domain-specific logic. The final revised model retained all essential pathways linking primary latent constructs to their respective subdimensions. As shown in Table 6, all standardized regression weights were statistically significant (p < 0.05), confirming that the items were strong indicators of their respective latent factors. This step ensured content validity and supported the coherence of the factor structure.

In addition to direct paths, the final model incorporated inter-factor covariances to account for system-wide interdependencies, a critical consideration in complex risk environments such as EFRTs. Table 7 summarizes these statistically significant covariance relationships. Most covariances among primary factors were positive and significant (p < 0.05), supporting the systemic, interrelated nature of fire and explosion risks.

Final structural model

The finalized structural model, developed in AMOS, captures the intricate web of interrelations among 11 validated latent constructs contributing to fire and explosion risk in EFRTs. As illustrated in Fig. 6, Operational Errors (OE) function as the central mediating construct, exhibiting strong direct effects on Maintenance Errors (β = 0.63), Tools Errors (β = 0.64), Static Electricity (β = 0.62), Open Flames (β = 0.66), Faulty Firefighting Systems (β = 0.53), and Sabotage (β = 0.66). This central positioning of OE suggests that breakdowns in procedural and human-system interfaces significantly propagate across both technical and emergency domains. In addition to these direct effects, OE mediates the influence of Natural Disasters (β = 0.54) and Runaway Reactions (β = 0.52), indicating that even externally triggered events often escalate through operational failures. These cascading pathways highlight the nonlinear propagation of risk, where single-point vulnerabilities, especially at the human interaction level, can activate multi-dimensional hazard chains. Covariance relationships, such as OE ↔ Maintenance Errors, OE ↔ Natural Disasters, and Tools Errors ↔ Sabotage, represent statistically significant but non-directional associations that reflect conceptual overlap and latent risk interdependencies. While not causal, these relationships inform the need for holistic control strategies that address co-occurring weaknesses in design, behaviour, and emergency preparedness.

Final structural model of risk factors for EFRT fire and explosion hazard Overall. the path model not only confirms the theoretical expectation of human error as a systemic initiator, (consistent with Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model) but also provides a validated framework for targeting intervention. Emphasis on proactive maintenance, operator training, and early error detection emerges as a critical strategy for mitigating cascading failures and enhancing EFRT safety resilience.

Case study validation

To verify the model’s practical applicability in real-world settings, a case study was conducted involving 11 operational EFRTs at a major petroleum refinery in Bandar Abbas. These tanks had no recorded history of fire or explosion events, making them ideal candidates for predictive evaluation. Using the finalized risk checklist, risk scores were computed for each tank based on expert input. The results were independently reviewed and confirmed by a panel of refinery engineers. As presented in Table 8, risk scores ranged from 0.591 to 0.950, reflecting substantial variation in relative hazard levels across the tank fleet.

To facilitate interpretation and practical use, the scores were classified into three risk categories:

-

High Risk (≥ 0.90): Immediate attention required.

-

Medium Risk (0.70–0.89): Monitoring and preventive action advised.

-

Low Risk (< 0.70): Acceptable under current controls.

Tanks #11 and #6 exhibited the highest risk levels, while tanks #3 and #8 demonstrated the lowest risk exposure.

Discussion

Interpretation of key findings

The findings of this study offer a comprehensive empirical depiction of the multidimensional nature of fire and explosion risks in EFRTs. Through sequential application of EFA, CFA, and path analysis, the research identifies 11 latent risk dimensions, each substantiated by multiple significant sub-factors. These dimensions span operational errors, maintenance failures, equipment degradation, structural vulnerabilities, and uncontrolled exothermic reactions, demonstrating the systemic character of EFRT safety hazards.

The findings of this study are strongly consistent with the core assumptions of Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model, which emphasizes that accidents often emerge from the alignment of multiple latent and active system-level failures. Rather than following a simple linear trajectory, these failures interact in nonlinear and compounding ways, gradually eroding organizational defences. This pattern is evident in the validated structural model, where operational errors significantly contribute to technical failures, which in turn escalate into fire suppression system breakdowns, demonstrating a clear cascade effect. The interconnected pathways revealed through path analysis reflect the model’s theoretical foundation: that each layer of protection may contain inherent vulnerabilities, and when these vulnerabilities coincide, the system becomes exposed to high-consequence events.

One key insight is the prominence of equipment failure (α = 0.73) and uncontrolled exothermic reactions (α = 0.82) as dominant contributors to fire/explosion risk, indicated by both high internal consistency and substantial standardized loadings in the CFA model. For example, sub-indicators such as TE3 (Pump failure) and S2 (Chemical instability) exhibited factor loadings above 0.7, signalling their critical roles in risk amplification.

In the path model, technical failures (TE) showed strong causal links to both structural integrity (TC) and safety system unreliability (FF), supporting the notion that mechanical degradation often triggers cascading system failures. This finding resonates with prior research, such as Feng et al. (2022)32, who emphasized the pivotal role of aging infrastructure in triggering compound incidents in power systems. Additionally, the significant covariance between operational error (OE) and maintenance error (ME) (β = 0.193, p < 0.001) confirms a tightly coupled relationship between procedural noncompliance and substandard maintenance routines.

Interestingly, fire suppression system faults (FF) retained structural significance in both CFA and path analysis stages. Specifically, FF2 (manual delay) and FF6 (valve malfunction) demonstrated meaningful pathways toward risk escalation, underscoring the critical, albeit underestimated, role of response system functionality.

In addition to identifying statistically significant pathways, it is essential to distinguish between direct and indirect relationships within the structural model to better understand the risk escalation mechanisms. Direct paths represent immediate cause-effect links between risk domains. However, the model also revealed critical indirect pathways that highlight the layered nature of risk propagation. For example, the pathway from OE to FF is not direct but mediated through TE, indicating that procedural lapses can lead to mechanical degradation, which in turn compromises safety system performance. This cascading sequence reflects a compound risk logic in which the failure of one subsystem amplifies vulnerabilities in others. Similarly, the influence of natural disasters (ND) on fire suppression reliability is partly mediated through their effect on structural vulnerability (TC), suggesting that environmental shocks may first destabilize physical infrastructure before degrading response capacity. These indirect pathways underscore the nonlinear, multi-stage dynamics of EFRT risk systems and reinforce the need for holistic risk assessments that go beyond isolated failure points.

The EFA-extracted factor structure explained approximately 72% of the total variance, which reflects a strong explanatory power given the multidimensional nature of the dataset. In terms of explained variance, the eleven extracted factors collectively accounted for 72.0% of the total variance. Among these, the top three contributors were Operational Error (OE, 9.00%), Maintenance Error (ME, 8.37%), and Technical Error (TE, 8.05%), highlighting their central role in shaping the underlying risk architecture. In contrast, Security System Error (SE) explained only 3.27% of the variance, indicating a more specialized or peripheral influence. This distribution suggests a balanced dimensional structure in which both dominant and less prominent but meaningful risk domains are preserved, enhancing the model’s interpretability and holistic scope.This level of cumulative variance aligns with prior research in behavioural and process safety domains, where values above 60% are typically considered acceptable for complex constructs. The retention of 11 factors strikes a balance between dimensional richness and statistical parsimony, ensuring that the model remains both interpretable and theoretically grounded. Although this percentage may appear conservative, it aligns with previous high-dimensional risk modelling studies such as Jia et al., (2024)15 and Moshashaei et al., (2018)16 where trade-offs between model complexity and parsimony were necessary.

Collectively, the model elucidates both direct and indirect pathways through which latent risk constructs interact and escalate. For instance, natural disasters (ND) exhibited statistically significant covariance with technical failure (TE) and risk response (RR) constructs (β = 0.184 and 0.113 respectively), reflecting how external environmental shocks can disrupt technical systems and challenge response protocols simultaneously. This multidirectional interdependence echoes the systems-theoretic perspective on industrial safety10, further justifying the study’s multivariate analytical approach.

This trade-off between statistical rigor and operational relevance was particularly evident in the handling of several risk indicators. Although several indicators were excluded during the EFA phase due to low communalities or weak factor loadings their removal was based strictly on statistical thresholds to ensure structural validity and factor clarity. However, these variables remain operationally critical from a safety management perspective, particularly in emergency response coordination and external agency alignment. Their exclusion from the final model does not imply irrelevance but rather reflects the limitations of the underlying dataset in capturing their variance. For practical applications, safety professionals are encouraged to retain and monitor these criteria as part of holistic risk management strategies, even if they are not statistically dominant within the latent structure.

In interpreting the refinement of the final structural model, it is important to note that several hypothesized causal paths were removed during the estimation process due to statistical insignificance (p > 0.05) and limited theoretical support. For example, the initially proposed directional relationship between operational error and sabotage, although conceptually plausible, failed to demonstrate empirical strength and may instead reflect an indirect association moderated by other latent variables. Likewise, the expected influence of redundant response on maintenance error lacked both statistical justification and conceptual clarity in the post-hoc analysis. Removing these paths improved the model’s parsimony and alignment with empirical reality, ensuring that retained linkages reflected both significant causal mechanisms and defensible theoretical logic. This refinement process contributes to the model’s explanatory robustness while acknowledging that certain relationships may require further exploration through scenario-based or longitudinal modelling.

While both the 11-factor and 12-factor models demonstrated acceptable levels of fit based on global indices (as shown in Table 5), a closer comparative analysis supports the retention of the 11-factor solution. Statistically, the 11-factor model yielded improved parsimony and more stable parameter estimates, with lower standard errors and higher factor loadings across retained constructs. Conceptually, the twelfth factor exhibited substantial cross-loadings with components from both the emergency response and sabotage domains, indicating construct redundancy rather than the presence of a distinct latent variable. Its inclusion also introduced model instability, reflected in increased modification indices and poor discriminant validity. Removing this factor allowed the 11-factor model to maintain theoretical coherence, reduce collinearity among latent constructs, and enhance the overall clarity of the structural relationships. As a result, the final model presents a more parsimonious and interpretable framework, better suited for practical application and theoretical generalization.

Finally, the model’s ability to stratify real-world tank risk levels, as demonstrated in the Bandar Abbas case study, supports its diagnostic strength. Tanks #11 and #6, which received the highest composite risk scores (> 0.93), aligned with expert assessments and scenario-based expectations, validating the predictive fidelity of the integrated model.

Interpretation and benchmarking against prior studies

The initial content validity was ensured through expert panel reviews and iterative feedback, resulting in a final instrument containing 71 sub-criteria across 11 primary dimensions. Internal consistency testing yielded Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.60 and 0.82, which aligns with the reliability coefficients reported by Sadeghi et al. (2020) in their combined-cycle power plant risk analysis (α = 0.62–0.79), and by Saloua et al. (2019)33, who found acceptable internal reliability scores (> 0.65) in petrochemical plant assessments using FTA. These comparisons validate the psychometric soundness of our instrument and demonstrate its consistency with models applied in other high-risk industrial sectors. The initial CFA model yielded suboptimal fit indices (CFI = 0.552, TLI = 0.533), indicating potential issues with model specification or complexity. Through iterative refinement, such as eliminating statistically insignificant paths, adjusting covariances among related factors (e.g., OE ↔ TE, OE ↔ S), and optimizing measurement relationships, the revised model achieved substantial improvement across all indices. The final CFA model demonstrated excellent fit (CFI = 0.915, TLI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.036), confirming the structural coherence and robustness of the extracted latent constructs.

Beyond the statistical structure, the model revealed conceptual overlaps between certain latent factors, particularly between emergency response (RR) and sabotage (S), as well as between firefighting failure (FF) and technical degradation (TE). While these constructs were retained as distinct domains based on empirical factor separation and theoretical relevance, their intercorrelations suggest that risk dimensions in EFRTs often do not operate in isolation. For instance, acts of sabotage may indirectly compromise emergency response effectiveness by disrupting communication lines or disabling key control systems50. Similarly, firefighting system unreliability may stem from underlying technical degradation, reflecting intertwined root causes51. These conceptual overlaps do not indicate model redundancy, but rather underscore the layered, systemic nature of risk interactions in high-hazard environments. Recognizing such overlaps enhances the interpretability of the structural model, encouraging a more integrated approach to risk mitigation that accounts for both independent and converging threat pathways.

The central role of operational error (OE) in the final model with prior research emphasizing human and procedural faults as primary initiators of major industrial accidents52,53. This finding is also consistent with Antonovsky et al. (2014)54, who identified operator behaviour as a pivotal contributor to cascading technical and safety failures in petroleum storage contexts. The dominance of OE in this study reinforces the theoretical proposition of Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model, wherein active failures act as triggers that penetrate system defences. Unlike purely technical hazard models, the current structure highlights the relational complexity between OE and downstream constructs such as sabotage, response failure, and maintenance errors, echoing the interconnected dynamics reported in studies by J Robert Taylor et al. (2020)55 and L Taylor et al. (2020)56. These comparative insights validate both the structure and practical interpretability of the proposed model within the broader literature on process safety and accident causation.

The centrality of OE in the structural model further reinforces long-standing theories in human reliability and systems safety. According to the Human Reliability Theory (HRT)57, human actions are among the most critical initiators of system failures in safety-critical domains. Similarly, the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS) developed by Shappell and Wiegmann (2000)58 categorizes operational errors as foundational to accident chains, often acting as catalysts that propagate latent failures through organizational layers. In the current model, OE demonstrated direct paths to multiple domains, including technical failure, sabotage vulnerability, and response unreliability, suggesting it acts not only as a primary trigger but also as an amplifier of cascading risks. This aligns with Rasmussen’s (1997) Risk Management Framework59, which views human operators as both the first line of defence and the most frequent point of breakdown. The model’s findings thus provide empirical support for the theoretical notion that improving operator training, decision-making protocols, and human-machine interfaces can yield system-wide safety benefits across EFRT facilities.

EFA grouped the data into 11 latent constructs. While largely consistent with the theoretical classification, minor regroupings emerged. Similar factor overlaps were reported by Moshashaei et al. (2018)16, who used expert consensus to prioritize EFRT fire causes and highlighted functional convergence between human error, training gaps, and maintenance deficiencies. This reinforces the notion that empirical factor structures can reflect operational realities more precisely than purely conceptual models. Several sub-criteria, including “use of explosion-proof equipment,” “insufficient foam and powder firefighting agents,” and “lack of coordination with urban firefighting services,” were removed due to low communalities or weak factor loadings. While statistically justified, these elements remain critical from a safety engineering standpoint. Studies such as Liu (2021)60 and Shaluf (2011)2 emphasize that fixed foam systems and inter-agency coordination are key components of effective EFRT risk mitigation.

CFA was applied to verify the structural validity of the 11-factor solution, resulting in fit indices that, while not optimal, were within the range seen in similar multidimensional studies. RMSEA (0.048) indicated good fit, while CFI (0.552) and TLI (0.533) were moderate, comparable to results from Makransky et al. (2017)61 and Wood et al. (2016)62, who reported similarly imperfect indices in complex behavioural models. Despite sub-threshold loadings for a few items, these were retained due to their operational significance, an approach also defended by Li et al. (2019)20 and Sarvestani et al. (2021)17, who argue that statistically weak indicators may still hold predictive or preventative value in applied environments.

During the CFA model refinement, notable shifts were observed in several factor loadings between the initial and final models. Items such as TE3 (Pump failure) and FF6 (Valve malfunction) showed increased standardized loadings following the removal of cross-loading indicators and the adjustment of residual covariances. This improvement suggests that these items better align with their latent constructs in the refined model. Conversely, a few items with marginal loadings in the initial CFA maintained relatively weak loading values and were excluded to enhance construct validity. These adjustments contributed to the improved internal consistency and convergent validity of the final factor structure, as reflected in the revised fit indices.

Compared to Zhang et al. (2016)10, who applied an AHP–FTA model to steel tank risks but lacked statistical validation of latent structures, the current study offers an advancement by incorporating EFA, CFA, and path analysis in a cohesive statistical workflow. The structural model not only confirmed construct reliability but also illuminated causal relationships between domains such as system reliability, environmental hazards, and human error, areas that Zhang’s ranking-based approach could not fully capture. Jia et al. (2024)15 similarly proposed a modified AHP method for EFRT risk but acknowledged the absence of empirical confirmation for the interrelationships among risk factors. This study addresses that gap, offering a data-driven causal network validated both statistically and through field application. Importantly, our case study validation across 11 EFRTs demonstrated that the model is not only theoretically sound but also capable of real-world risk discrimination. Tanks #11 and #6, which scored highest in the model (0.950 and 0.934), were independently flagged by refinery engineers as high-priority sites, highlighting the model’s diagnostic accuracy. This practical validation contrasts with earlier studies, including those by Sadeghi et al. (2020)36 and Moshashaei et al. (2018)16, which relied primarily on simulations or expert judgment.

Finally, the model’s path analysis component provides a distinctive contribution by mapping causal escalation routes between risk domains, an approach absents in most previous EFRT studies. While Saloua et al. (2019)33 and Zhang et al. (2016)10 focused on static fault hierarchies or consequence estimation, this study emphasizes system dynamics and interdependencies, reflecting the need for predictive, actionable frameworks in high-hazard industries.

Scientific contributions and novelty

This study introduces a validated, data-driven framework for assessing fire and explosion risks in EFRTs, offering methodological and conceptual advancements over prior research.

First, the sequential application of EFA, CFA, and path analysis distinguishes this work from traditional models like AHP or FTA, which often lack empirical validation. The current approach enables both factor identification and causal interpretation, filling a key methodological gap noted in studies like Zhang et al. (2016)10 and Jia et al. (2024)15.

Second, while the extracted factor structure aligned with the initial theoretical model, certain merged constructs, such as firefighting and maintenance failures, revealed latent interdependencies often overlooked in previous frameworks16,33.

Third, unlike many prior models, this study underwent real-world validation using data from 11 operational EFRTs. The model’s ability to distinguish between high- and low-risk tanks confirmed its predictive value, supporting its practical utility36.

Fourth, the proposed model integrates human, technical, environmental, and organizational dimensions, aligning with systems-based safety perspectives seen in more recent literature17.

Unlike previous studies relying on expert judgment or simulation-based risk ranking, this study provides an empirically validated causal framework that integrates latent construct verification and dynamic risk interaction analysis. This integrated structure allows for more robust interpretation of the interdependencies among risk dimensions and enhances predictive capability by linking data-driven factor identification (via EFA/CFA) with theory-informed causal modelling (through Path Analysis). Consequently, the proposed model bridges the gap between statistical validation and practical risk interpretation, offering a scientifically rigorous yet operationally meaningful advancement over existing EFRT safety assessment frameworks. Finally, the model’s scalable architecture allows adaptation to other high-risk sectors, making it suitable for integration with AI-driven monitoring or real-time data systems. In summary, this study bridges theory and application by offering a robust, generalizable, and empirically validated risk modelling framework for EFRTs.

Practical and policy implications

The findings of this study offer clear implications for both safety practitioners and regulatory authorities involved in the management of EFRTs.

-

I.

Operational guidance:

The final structural model identifies key leverage points dominant contributors to risk escalation. This provides facility managers with a diagnostic tool to prioritize safety investments and allocate resources where they are most impactful. For example, tanks #11 and #6, which exhibited the highest composite risk scores in the case study, can be flagged for immediate intervention without requiring a full-scale audit.

-

II.

Standardized risk profiling:

The integration of latent constructs validated through EFA, and CFA allows for repeatable and standardized risk assessment across tank farms. Unlike traditional checklists that vary in content and interpretation, this model can serve as a benchmarking framework to compare safety performance across different sites or over time, thereby supporting compliance auditing and internal risk reviews.

-

III.

Emergency planning and response:

The model reinforces the importance of organizational readiness which are often underemphasized in conventional hazard identification techniques like HAZOP or FTA. Embedding these validated constructs into emergency protocols can enhance both reactive and proactive strategies, as supported by findings from Saloua et al. (2019)33 and Liu (2021)60.

-

IV.

Policy formulation:

Regulators can adopt the model’s validated indicators and thresholds as a foundation for developing or updating national safety standards for aboveground fuel storage. As noted by Moshashaei et al. (2018)16, current guidelines often lack structure-specific risk metrics tailored to EFRTs. The predictive structure proposed here can support risk-based inspection regimes and insurance underwriting decisions. The validated framework developed in this study aligns conceptually with several key industrial safety standards and regulatory protocols. The identified factors such as maintenance deficiencies, technical failure, and emergency response gaps correspond to critical control elements outlined in NFPA 30, API Standard 2000, and ISO 23,251. Although these standards provide procedural and engineering-based safeguards, the current model adds value by offering a behavioural and organizational risk perspective that is often underrepresented in prescriptive codes.

-

V.

Scalability and digital integration:

Given its statistical rigor, the model lends itself to integration with digital twin platforms, AI-based inspection systems, or real-time monitoring tools. This aligns with recent technological shifts in smart safety infrastructure observed in high-risk sectors.

Limitations and future research directions

Despite the methodological strengths of this study, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively limited due to restricted access and insufficient cooperation from oil and gas companies. Second, the checklist development and risk scoring processes relied on expert judgment, which inherently carries a degree of subjectivity. While statistical tools such as EFA and CFA were applied to reduce bias and ensure construct validity, individual interpretation may still have influenced the factor structure and prioritization of risk elements.

Future research could address these limitations by expanding sample coverage, incorporating demographic profiling, and integrating more objective data sources such as real-time monitoring systems or historical incident records. Moreover, cross-validation of the proposed model in different industrial or geographic contexts would enhance its robustness and practical relevance.

While the current structural model captures significant causal and correlational relationships between key risk domains, it assesses them as discrete and linear paths. However, in real-world EFRT incidents, multiple risk factors often interact simultaneously, leading to nonlinear escalation patterns. For instance, an operational error occurring in parallel with sabotage or technical failure may result in disproportionately severe outcomes. Future research should explore scenario-based risk modelling, potentially using Bayesian networks, FTA/ETA, or dynamic probabilistic models to simulate how concurrent or cascading failures evolve over time. Incorporating these methods would allow for more robust and realistic safety analysis under complex, uncertain conditions.

Beyond its theoretical and analytical contributions, the proposed structural model holds promise for real-world deployment in intelligent early warning systems. By linking the identified latent risk factors with real-time data inputs from IoT-based monitoring platforms the model can be transformed into a predictive risk dashboard. Such an integration would allow site managers to monitor evolving risk patterns, receive automated alerts, and proactively mitigate cascading failures. Future research should explore the technological and computational integration of this framework into smart safety management systems across high-risk industrial environments.

Conclusion

This study developed and empirically validated a comprehensive structural model to identify, categorize, and explain the latent risk factors contributing to fire and explosion hazards in external EFRTs. Integrating EFA, CFA, and path analysis enabled the research to move beyond conventional risk-ranking approaches and establish a theory-driven framework that captures both the structural composition and dynamic interactions of interdependent risk constructs. This study contributes to the literature and industry practice by offering a novel, empirically validated structural model tailored specifically to the context of fire and explosion risks in EFRTs. Unlike previous studies that have focused on isolated factors or descriptive statistics, this research integrates EFA, CFA, and path modelling to develop a multi-dimensional, causal framework. The model captures complex interdependencies between organizational, technical, and emergency response variables, offering both theoretical advancement and practical insights. Furthermore, it addresses a critical gap in the risk modelling of EFRTs, which are underrepresented in current quantitative safety research. The framework has potential application in designing targeted safety interventions, informing regulatory policies, and supporting predictive risk analytics in high-hazard storage environments.

The final model consisted of 11 latent dimensions covering technical, operational, environmental, and human-related risk domains. Internal consistency across these constructs was statistically acceptable, and model fit indices confirmed the structural validity of the proposed framework. The findings also highlighted causal pathways among risk factors, identifying critical leverage points such as equipment malfunction, insufficient training, and inadequate fire suppression readiness. Case study validation on 11 EFRTs further demonstrated the model’s practical utility and discriminatory power in real-world risk differentiation.

In summary, this study presents a validated structural framework that identifies and interrelates key risk factors contributing to fire and explosion hazards in EFRTs. While the findings offer strong empirical and theoretical grounding, the practical value of the model lies in its potential application across industrial safety domains. For example, the identified causal chains, such as the path from operational error to fire suppression failure, can directly inform maintenance planning, incident investigation protocols, and targeted safety training programs in oil storage facilities.

Future studies are encouraged to expand on this work by applying the model to alternative high-risk infrastructures, such as fixed-roof tanks or offshore terminals. Additionally, integrating the framework with real-time data streams from IoT-based monitoring systems facilitate predictive analytics and early warning mechanisms. Such integration would strengthen the model’s utility as a proactive decision-support tool in dynamic and data-rich industrial environments.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are held by the corresponding author and are available upon reasonable request.

References

Litvinenko, V. The role of hydrocarbons in the global energy agenda: the focus on liquefied natural gas. Resources 9 (5), 59 (2020).

Shaluf, I. M. & Abdullah, S. A. Floating roof storage tank boilover. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 24 (1), 1–7 (2011).

Pasley, H. & Clark, C. Computational fluid dynamics study of flow around floating-roof oil storage tanks. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 86 (1), 37–54 (2000).

Necci, A. et al. Accident scenarios caused by lightning impact on atmospheric storage tanks. Chem. Eng. Trans. 32, 139–144 (2013).

Al Omari, A. et al. Floating roof storage tanks life extension: A novel risk revealed. In Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition and Conference. (SPE, 2019).

Moshashaei, P. et al. Investigate the causes of fires and explosions at external floating roof tanks: A comprehensive literature review. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 17, 1044–1052 (2017).

Noaman, A. S., El-Samanody, M. & Ghorab, A. Design and study of floating roofs for oil storage tanks. Int. J. Eng. Dev. Res 4, 41-12-1–12 (2016).

Zinke, R. et al. Quantitative risk assessment of emissions from external floating roof tanks during normal operation and in case of damages using Bayesian networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 197, 106826 ( 2020).

Pouyakian, M. et al. A comprehensive approach to analyze the risk of floating roof storage tanks. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 146, 811–836 (2021).

Zhang, M. et al. Risk assessment for fire and explosion accidents of steel oil tanks using improved AHP based on FTA. Process Saf. Prog. 35 (3), 260–269 (2016).

Suardin, J., Mannan, M. S. & El-Halwagi, M. The integration of dow’s fire and explosion index (F&EI) into process design and optimization to achieve inherently safer design. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 20 (1), 79–90 (2007).

Li, H., Zhang, Y. & Yang, W. Gas explosion early warning method in coal mines by intelligent mining system and multivariate data analysis. PLoS One. 18 (11), e0293814 (2023).

Watkins, M. W. Exploratory factor analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 44 (3), 219–246 (2018).

Al Zarooni, M., Awad, M. & Alzaatreh, A. Confirmatory factor analysis of work-related accidents in UAE. Saf. Sci. 153, 105813 (2022).

Jia, P. et al. Modified analytic hierarchy process for risk assessment of fire and explosion accidents of external floating roof tanks. Process Saf. Prog. 43 (1), 9–26 (2024).

Moshashaei, P. et al. Prioritizing the causes of fire and explosion in the external floating roof tanks. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 18, 1587–1600 (2018).

Sarvestani, K., Ahmadi, O. & Alenjareghi, M. J. LPG storage tank accidents: initiating events, causes, scenarios, and consequences. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 21 (4), 1305–1314 (2021).

Attia, M. & Sinha, J. Improved quantitative risk model for integrity management of liquefied petroleum gas storage tanks: mathematical basis, and case study. Process Saf. Prog. 40 (3), 63–78 (2021).

He, J. et al. Simulation and application of a detecting rapid response model for the leakage of flammable liquid storage tank. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 141, 390–401 (2020).

Li, M., Wang, D. & Shan, H. Risk assessment of mine ignition sources using fuzzy Bayesian network. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 125, 297–306 ( 2019).

Cheng, Y. & Luo, Y. Analysis of Natech risk induced by lightning strikes in floating roof tanks based on the bayesian network model. Process Saf. Prog. 40 (1), e12164 (2021).

Soltanzadeh, A. et al. Incidence investigation of accidents in chemical industries: A comprehensive study based on factor analysis. Process Saf. Prog. 41 (3), 531–537 (2022).

Upadhyaya, D. & Malek, M. S. An exploratory factor analysis approach to investigate health and safety factors in Indian construction sector. Constr. Econ. Building. 24 (1–2), 29–49 (2024).

Mohammadfam, I. et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of occupational injuries: Presenting an analytical tool. Trauma Mon. 22(2) (2017).

Rahlina, N. A. et al. The art of covariance based analysis in behaviour-based safety performance study using confirmatory factor analysis: evidence from SMES. Measurement 7(10) (2019).

Gerassis, S. et al. Understanding complex blasting operations: A structural equation model combining bayesian networks and latent class clustering. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 188, 195–204 (2019).