Abstract

The physical fitness level of Chinese adolescents shows a decreasing trend year by year, which hurts adolescents’ physical health and future achievements. The weight-adjusted waist index (WWI), as a new type of index for assessing adolescents’ body composition, has received extensive attention in recent years. However, little research has been conducted on the association between WWI and the physical fitness index (PFI) among Chinese adolescents nationwide. In this study, 9204 adolescents aged 13–18 years from different regions of China were assessed for weight, waist circumference, grip strength, standing long jump, sit-up, sit and reach, and 1000/800 m run using stratified whole-cluster random sampling, and a 50 m dash was assessed. WWI and PFI of the participants were derived sequentially. The t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis H test, Pearson correlation analysis, and curvilinear regression analysis were used to analyze the associations existing between WWI and PFI. The WWI of Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years was (9.34 ± 1.14) cm/kg; the PFI was − 0.02. Overall, the results of the analysis showed that the differences in PFI between the different WWI groups were statistically significant in the 13–15 and 16–18 age groups (H-value 19.673, 29.177, P-value < 0.001). The highest level of PFI in adolescents was 0.021 when the WWI was 8.2. The association between WWI and PFI among Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years was characterized by an inverted “U” curve, with both lower and higher WWI negatively affecting physical fitness. The effect of WWI on PFI was more pronounced in boys than in girls. In the future, changes in WWI should be considered in the promotion and intervention of physical fitness, to keep WWI in the normal range and promote the improvement of physical fitness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As lifestyles change, levels of physical fitness among adolescents are trending downward, negatively impacting mental health and future achievement1. The study shows that globally, up to 81% of adolescents between the ages of 11 and 17 years do not meet the minimum physical activity standards set by the World Health Organization (WHO) and continue to show a downward trend, which has a serious negative impact on the physical fitness of adolescents2. China is no exception, with surveys showing that less than a quarter (22%) of Chinese schoolchildren engage in physical activity lasting 60 min or more every day, and that this is generally on the decline3. There are also studies confirming that the decline in physical activity levels among adolescents has led to a sustained increase in overweight and obesity rates, which has hurt adolescent physical fitness. A survey of American adolescents showed that adolescent physical fitness showed a downward trend, manifested in the decline of muscle strength and cardiorespiratory fitness level. American adolescents’ cardiorespiratory fitness compliance rate fell from 54.1% to 42.2%4. Another survey of British teenagers also showed a downward trend in fitness levels between 2014 and 2019, mainly in the form of a 1.16-centimetre drop in the standing long jump and a 1.85-times drop in the 20-metre dash5. Similarly, some studies confirm the association between decreased levels of physical fitness and an increased risk of all-cause mortality. One study analyzing data from 750,000 people found that reduced levels of cardiorespiratory fitness were significantly associated with all-cause mortality risk, with participants in the lowest cardiorespiratory fitness group experiencing a 309% increased risk of all-cause mortality6. It has also been found that declining levels of physical fitness in adolescents can lead to elevated mental health problems. One study showed that among Chinese adolescents, the overall detection rate of mental subhealth among adolescents with high levels of physical fitness was 11.9%, while the detection rate among adolescents with low levels of physical fitness was 26.0%7. In addition, physical fitness hurts future employment and achievement. Thus, it is clear that the level of physical fitness of adolescents has a serious impact on health. The PFI, as an aggregate indicator for assessing physical fitness among adolescents, has received extensive attention from scholars around the world in recent years, and the number of related studies has been increasing8. A study of global trends in adolescent physical fitness from 1972 to 2015 showed that adolescent physical fitness showed a wavy trend of rising and then falling. However, this trend is no exception in developing countries. A survey of Chinese adolescents showed a downward trend in PFI year by year, with PFI decreasing by 0.8 from 1985 to 2014, with obese boys showing a more pronounced decline in PFI than girls9. A meta-analysis of school-age children in sub-Saharan Africa shows that school-age children spend more time in sedentary behaviors, further leading to reduced physical fitness levels10. The decline in PFI should be given sufficient attention and importance to better promote the healthy physical and mental development of adolescents. However, relatively few past studies have been conducted on PFI for Chinese adolescents nationwide, for which investigations and studies are necessary.

WWI has received much attention from scholars as a novel indicator for assessing body composition in recent years11,12. Studies have shown that WWI is more effective in assessing all-cause mortality risk than BMI and waist circumference metrics. It has also been shown that a study comparing the effectiveness of BMI, WC, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and WWI in predicting health risks suggests that WWI is more advantageous in assessing the risk of central obesity and related diseases13. One study confirmed that both BMI and waist circumference showed a significant negative correlation with body quality, while no correlation was observed with forward flexion of the seat14. Another cross-sectional study based on NHANES data found that WWI was significantly associated with the risk of osteoarthritis, and that increased abdominal fat distribution was associated with an elevated risk of osteoarthritis15. A survey of Chinese adolescents aged 12–17 showed that there is an inverted “U” curve association between WWI and physical fitness index (PFI), with an optimal WWI threshold of 8.8, and that boys’ PFI is more significantly affected by WWI16. It has also been shown that WWI combines changes in weight and waist circumference to better identify physical health conditions17. The study confirmed that for every 1-unit increase in WWI, the risk of all-cause mortality increased by 13%; furthermore, after excluding patients with major cardiovascular disease and cancer, the positive association between WWI and the risk of all-cause mortality remained significant (HR = 1.27, 95% CI: 1.12–1.44)18. This shows that there is a strong association between WWI and all-cause mortality, which is an important indicator for identifying mortality risk. However, there are relatively few studies on the association between WWI and mental health. Only some studies have found that elevated WWI leads to a decrease in mental health, which hurts the development of adolescent mental health1920. One study also confirmed that WWI was more effective in identifying the onset of mental health problems in adolescents compared to BMI21. A study based on NHANES data analyzing 38,154 participants found that higher WWI was significantly associated with higher depression scores (β = 0.41; 95% CI, 0.36–0.47), and that WWI had better discriminatory power and accuracy in identifying participants’ depressive symptoms compared with BMI and other obesity indicators22. It can be seen that there is a close association between WWI indicators and physical and mental health status, and a better analysis of WWI indicators will have important practical significance for adolescents’ physical and mental health development. However, most of the past studies have focused on the association between WWI and certain diseases, such as all-cause mortality risk, depression, anxiety, etc., and fewer studies have been conducted on Chinese adolescents. Even fewer studies have been conducted on the association between WWI and PFI, which is a composite measure of physical fitness in adolescents, and even fewer studies have been conducted on the association between WWI and PFI, which is a composite measure of physical fitness in adolescents, and even fewer studies are needed.

China’s north-south and east-west regions span a wide range of areas, and there are large differences in their natural environments and dietary behaviors. The differences between east and west and north and south have led to large differences in the physical fitness levels of Chinese adolescents23. For this reason, it is necessary and meaningful to investigate and analyze the level of physical fitness among Chinese adolescents nationwide. Past studies have found that there are fewer studies on the association between WWI, which reflects the body composition of adolescents, and the PFI, which is a composite indicator of physical fitness. Even fewer studies have been found to address the association between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents nationwide. For this reason, the present study used a nationwide multicenter sample to analyze the association between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents, to better promote the improvement of adolescents’ physical fitness level, and to promote the development of physical and mental health.

Methods

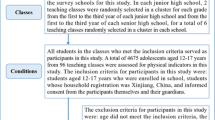

Participants

In this study, participants were sampled using stratified whole cluster random sampling. In the first step, Changchun, Guangzhou, Xi’an, and Chizhou in the northern, southern, western, and eastern regions of China were selected as the sampling areas for this study based on the division of China into different geographic regions. In the second step, two secondary schools were randomly selected in each city as the sampling schools for the participants of this study. In the third step, in each school, 3 teaching classes were randomly selected in whole clusters for each grade according to grade level. All students who met the inclusion conditions of this study were assessed for relevant indicators as participants of this study. The inclusion criteria for this study were: adolescents aged 13–18 years enrolled in school, who volunteered to be assessed for this study, and received informed consent from their parents. In the end, a total of 9456 adolescents aged 13–18 years from 144 teaching classes in 8 schools in 4 cities were assessed in this study. After the assessment, 252 invalid questionnaires were excluded, and a total of 9204 valid questionnaires were returned (4637 boys, 50.4%), resulting in a valid return rate of 97.34%.

This study is a current situation survey research, and the research indicators are count data, so the sample estimation calculation formula is:\(\:n=\frac{Z{a/2}^{2}\times\:p\left(1-p\right)}{{d}^{2}}\), d = 0.15 × P, α = 0.05 (bilateral), \(\:Z{a/2}^{2}\)= 1.96. Based on the actual research and the 10% loss to follow-up rate, this study needed to evaluate 8941 people, and the final number of people actually evaluated in this study was 9204, which is representative.

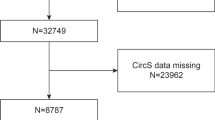

The participant extraction process is shown in Fig. 1.

This study was conducted by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians before the assessment of participants in this study, and participants volunteered to be assessed for this study. Approved by the human ethics committee of Xinjiang Normal University (0894157).

Weight-adjusted waist index (WWI)

The WWI is calculated by dividing the waist circumference (cm) by the square root of weight (kg). Thus, waist circumference is normalized to body weight, combining the waist circumference indicator24. The formula for calculating WWI was WC (cm)/√Weight (kg). The unit of WC is centimeters, and the unit of weight is kilograms. Weight and waist circumference were assessed by the methods and instruments of the China National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH)25. Body weight was assessed using a SENSSUN (Model S3) scale. Participants were asked to empty their bowels and urine before assessment. The participants were asked to wear as little clothing as possible for the assessment. The weight was assessed using a standard nylon tape measure. The waist circumference was assessed by asking the participant to stand naturally with shoulders relaxed, arms crossed in front of the chest, keep breathing calmly, and wrap the tape around the waist at a point 1 cm above the navel to check the assessment result. The results of the waist circumference assessment are accurate to 0.1 cm.

Physical fitness index (PFI)

The PFI was developed by standardizing and summing items related to physical fitness to provide a comprehensive picture of adolescents’ physical fitness. The PFI in this study mainly consists of physical fitness programs: Grip strength, Standing long jump, Sit-up, Sit and reach, 1000/800 m run, and 50 m dash. In this study, PFI mainly consists of physical fitness items: grip strength, standing long jump, sit-up, sit and reach, 1000/800 m run, and 50 m dash items.1000/800 m run scores were used to derive adolescents’ VO2max26. The formula has been widely used among Chinese adolescents and has good reliability and validity26. The assessment methods of each physical fitness item in this study were based on the instruments and methods required by the CNSSCH25. The results of Grip strength were accurate to 0.1 kg, standing long jump and sit and reach were accurate to 0.1 cm, Sit-up was accurate to 1 repetition, 1000/800 m run was accurate to 1 s, and 50 m dash was accurate to 0.01 s. In this study, each physical fitness item was stratified by age and gender and calculated by Z-score. The specific calculation of PFI in this study is: PFI = Z grip strength Z standing long jump+Z sit−up+Z sit and reach+Z VO2max-Z 50 m dash.

Quality control

The assessors in this study were rigorously trained and passed the examination before they were allowed to carry out the assessments. Before each day’s assessment, the staff needed to calibrate the instrument to ensure the accuracy of the test. Participants were required to do preparatory activities before the assessment to prevent the occurrence of sports injuries. During the assessment, participants are required to wear sportswear for the test.

Statistical analysis

In this study, 9204 adolescents aged 13–18 years from different regions of China were assessed for weight, waist circumference, grip strength, standing long jump, sit-up, sit and reach, and 1000/800 m run using stratified randomized whole cluster sampling; the 50 m dash was assessed. The WWI and PFI of the participants were derived sequentially. Continuous variables that conformed to the normal distribution after a normality test in this study were expressed as mean and standard deviation. For indicators that do not conform to a normal distribution, such as PFI, it was expressed as the median. Comparisons of assessment results between different sexes were performed using the t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test. For the correlations between different indicators, the method of Pearson Correlation Analysis was used. Comparisons of PFI levels between WWI groups were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test, and the correlations between WWI and PFI were analyzed using curvilinear regression analysis. Based on the fact that PFI showed a tendency to increase and then decrease between different WWI groups, the hypothesis of a quadratic association between PFI and WWI was proposed. To verify whether this hypothesis was valid, a linear regression model with PFI as the dependent variable and WWI as the independent variable was established: PFI = a WWI 2 + b WWI + c. Where a is the coefficient of the quadratic term of the equation, b is the coefficient of the primary term, and c is a constant. Data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 software, with P < 0.01 as the two-sided test level.

Results

In this study, 9,204 Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years were assessed for indicators related to WWI and PFI. Among them, 4637 were boys, accounting for 50.4%, and 4567 were girls, accounting for 49.6%, and the difference in the distribution of numbers between the sexes was not statistically significant when compared with each other (χ2 value = 1.065, P > 0.05).

Table 1 shows that the AGE of Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years was (15.50 ± 1.70) years, and there was no statistically significant difference when comparing between sexes (t-value of -0.037, P > 0.05). The weight of Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years was (56.28 ± 12.19) kg, waist circumference was (69.65 ± 11.03) cm, WWI was (9.34 ± 1.14) cm/kg, grip strength was (31.44 ± 10.00) kg, standing long jump was (188.25 ± 33.44) cm, sit-up was (23.01 ± 6.92) cm, sit and reach was (38.69 ± 11.73) repetitions, VO 2max was (39.37 ± 5.67) mL/(kg-min), and 50 m dash was (8.54 ± 1.26) s. The differences between the items The differences were statistically significant when compared between sex (t-values were 36.66, 26.945, 4.138, 64.685, 78.418, 25.14, -5.373, 33.879, and − 60.565, with P-values < 0.001). In this study, the PFI of Chinese adolescents was − 0.02, and the difference was not statistically significant when compared between sexes (Z-value − 0.567, P-value 0.571).

Pearson’s correlation analysis showed that among Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years, there were significant correlations between all indicators (P values < 0.05 or 0.01) except for no significant correlations between standing long jump and sit and reach, and sit and reach and 50 m dash. The specific correlation coefficients are shown in Table 2.

Table 3 shows the comparison of PFI among different WWIs in Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years. Since the PFI was not normally distributed, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to compare the PFI between the different WWI groups. The results showed that the difference in PFI between the different WWI groups was statistically significant for boys in the 13–15 and 16–18 age groups (H-values of 19.510 and 21.676, P-values < 0.001). In girls only, in the age group of 16–18 years, there was a statistically significant difference between the different WWI groups when comparing the PFI (H-value of 18.618, P < 0.001). Overall, the results of the analysis showed statistically significant differences in PFI between WWI groups in the 13–15 and 16–18 age groups (H-value 19.673, 29.177, P-value < 0.001).

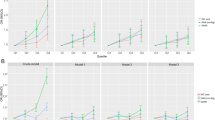

Figure 2 shows the trend of the PFI percentile of Chinese adolescents aged 13–18. In overall terms, the figure shows that the PFI of Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years shows a gradual increasing trend with the increase of the percentile. Boys’ PFI was lower than girls’ until the 37th percentile, and then boys were higher than girls. The PFI of boys increased from − 6.33 at P1 to 6.04 at P99, and that of girls increased from − 5.59 at P1 to 5.86 at P99.

Stratified by sex, a curvilinear regression analysis was performed with WWI as the independent variable and PFI as the dependent variable, and the following curvilinear regression equation was obtained:

Boys: PFI=-0.039WWI 2+0.619WWI-2.376 R2 = 0.005.

Girls: PFI=-0.018WWI 2+0.329WWI-1.504 R2 = 0.001.

Total: PFI=-0.032WWI 2+0.531WWI-2.182 R2 = 0.002.

Figure 3 shows the trend of the association between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years. As can be seen from the figure, the association between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents shows an inverted “U” curve, i.e., both lower and higher WWI negatively affect adolescents’ PFI, especially when adolescents’ WWI exceeds the normal range, the PFI shows a rapid decline. Concerning sex, it can be seen that the effect of WWI on PFI is more significant in boys than in girls, i.e., as WWI rises, the effect on PFI is more significant. Overall, the analysis showed that PFI was at its highest value (0.021) when WWI was 8.2 in Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years.

Discussion

The results of this study showed that WWI was significantly higher among Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years old in boys than in girls, and this result is consistent with the findings of related studies23. There are several reasons for this result: firstly, in terms of body shape, the waist circumference of boys is generally higher than that of girls, which is why the WWI is higher for boys than for girls27. Secondly, due to the influence of innate personality factors, the pursuit of dietary behavior and external physical beauty of the body is relatively lower than that of girls, resulting in less control of energy intake in the diet, which leads to the occurrence of overweight and obesity behaviors, increasing the level of waist circumference, which is also an important reason why the WWI of boys is higher than girls’27. Thirdly, the age group of 13–18 years old is at the peak of pubertal development, and the development of girls at this stage is 1–2 years later than that of boys, and the imbalance in the sexes in pubertal development leads to a higher level of waist circumference in boys than in girls, which in turn causes the WWI to be higher in boys than in girls, which is also one of the important reasons28. Studies have confirmed that boys at puberty develop 1-1.5 years earlier than girls, and that girls’ puberty comes relatively late29. In addition, the results of this study also show that as the PFI percentile gradually increases from low to high, the PFI value of boys gradually changes from lower than girls to higher than girls. The reason for this result may be that, due to genetic factors, the physical fitness levels of boys vary greatly, while the physical fitness levels of girls are relatively concentrated, and the change in physical fitness levels is not large, which is consistent with the relevant research conclusions30.

The PFI standardizes different physical fitness indicators and then adds them up, which can reflect the physical fitness level of adolescents to a certain extent. This indicator has been widely used by scholars in recent years31. The results of this study showed that PFI was higher among Chinese adolescents aged 13–18 years old in boys than in girls, a finding that is consistent with the findings of several studies32,33. The reasons for this are as follows: Firstly, under the influence of innate sex factors, boys are more active and can actively participate in more physical exercises in their lives, which leads to the overall physical fitness level of boys being higher than that of girls, and this is one of the important reasons. Research confirms that boys’ physical fitness levels in standing long jump, muscle strength, speed, and explosive power are higher than those of girls, which is related to the differences in muscle strength and body shape caused by their innate sex30. Second, studies have shown that boys’ physical activity levels are lower compared to girls’, and that the significant association between physical activity levels and multiple levels of physical fitness is also an important reason for boys’ higher PFI than girls’34. Third, due to a combination of genetic factors, testosterone levels are higher in boys than in girls, which also contributes significantly to the higher PFI in boys than in girls. Research shows that testosterone is an important androgen, which promotes protein synthesis, thus facilitating muscle growth and repair. In boys from puberty, muscle mass will grow rapidly, muscle fibers are thicker, resulting in reflecting the level of physical fitness the level as muscular strength, explosive power, cardiorespiratory endurance, etc., significantly higher than the level of girls35.

The results of this study also showed that the WWI of Chinese adolescents was divided into quartiles, and in general, it could be seen that the WWI at the Q1 and Q2 levels had relatively high levels of PFI in their adolescents. Further, the results of the curve regression analysis showed that with the gradual increase of WWI, the PFI showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, a result that is consistent with the findings of the relevant study. The results of the study in question showed the same trend for adolescent BMI, waist circumference, and PFI31. There are several reasons for this: first, increased WWI levels result in increased body weight, which in turn results in greater resistance to physical fitness assessment, leading to a decrease in physical fitness. Secondly, the increase in WWI is dominated by an increase in abdominal fat, which leads to an increase in the body’s demand for oxygen, which requires more oxygen during the physical fitness assessment and puts a greater demand on the heart, leading to a decrease in PFI levels. In addition, elevated WWI brings about elevated abdominal fat, and the accumulation of abdominal fat leads to disorders in lipid metabolism, resulting in elevated levels of cholesterol, triglycerides and other lipids in the blood, and high blood lipids increase the viscosity of the blood, which makes the blood flow more slowly, and tends to form plaques on the walls of the blood vessels. These plaques will gradually block the blood vessels, leading to narrowing of the blood vessels, reducing the blood supply, and one of the major causes of lower PFI36. However, it is interesting to note that the effect of WWI on PFI was more pronounced in boys compared to girls, especially as WWI was higher than the normal range, and the effect of elevated WWI on PFI was more pronounced in boys than in girls. This may be because boys have a higher level of physical fitness than girls. Elevated WWI will inevitably lead to an increase in body weight, which will result in a significant decrease in the levels of muscular strength, explosive power, and cardiorespiratory endurance, which reflect physical fitness, thus leading to a more significant effect of WWI on PFI in boys37.

There are certain strengths and limitations of this study. Strengths: First, to the best of our knowledge, this study analyzed for the first time the association that exists between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents, which provides a reference and a basis for the improvement and intervention of physical fitness level in Chinese adolescents. Second, the present study was conducted using a national multicenter cross-sectional sample, which is representative. However, this study also has some limitations. First, this study was a cross-sectional analysis, which could only analyze the association that exists between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents, but could not understand the causal association that exists between them. A longitudinal cohort study should be conducted in the future to analyze the causal associations. Second, limited covariates were included in the analysis of this study. In order to better analyze the association between WWI and PFI, more covariates should be included in future analysis, such as adolescent maturity, dietary behavioral habits, sleep, and other factors. In addition, this study uses the PFI comprehensive response to the physical fitness level of adolescents. Whether it has certain limitations due to the different effects and benefits of different projects on health needs to be further studied and demonstrated. Furthermore, although this study selected adolescents from four different regions in China for assessment, its representativeness may still be insufficient, and the sample size is limited, which may have a certain bias from the actual results. More extensive evaluations, such as multi-country evaluations and mixed-methods research designs, should be conducted in the future to improve the reliability and representativeness of the results. At the same time, machine learning methods can also be used for analysis to improve the depth of research and analysis.

Conclusions

There is an inverted “U” curve association between WWI and PFI in Chinese adolescents aged 13–18, i.e., as WWI increases, PFI shows a tendency to increase and then decrease. The highest level of PFI was found when WWI was 8.2. Compared with Chinese adolescent girls, the effect of WWI on PFI was more significant in boys. This study suggests that the changes in WWI should be taken into account when intervening on physical fitness level in the future, and that effective control of abdominal obesity may play a positive role in improving physical fitness level. Therefore, in the future, we should focus on increasing abdominal muscle strength exercises, such as sit-ups, crunches, and other exercises.

Data availability

To protect the privacy of participants, the questionnaire data will not be disclosed to the public. If necessary, you can contact the corresponding author.

References

Liang, W. et al. Associations of reallocating sedentary time to physical activity and sleep with physical and mental health of older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 56, 1935–1944 (2024).

Belhaj, M. R., Lawler, N. G. & Hoffman, N. J. Metabolomics and lipidomics: expanding the molecular landscape of exercise biology. Metabolites 11, 151 (2021).

The, W. Report on cardiovascular health and diseases in China 2022: an updated summary. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 36, 669–701 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Chan, D., Pan, Q., Rhodes, R. E. & Tao, S. National trends and ecological factors of physical activity engagement among U.S youth before and during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cohort study from 2019 to 2021. Bmc Public. Health. 24, 1923 (2024).

Weedon, B. D. et al. Declining fitness and physical education lessons in Uk adolescents. Bmj Open. Sport Exerc. Med. 8, e1165 (2022).

Kokkinos, P. et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and mortality risk across the spectra of Age, Race, and sex. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 598–609 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. The influence of physical exercise on adolescents’ negative emotions: the chain mediating role of academic stress and sleep quality. Bmc Pediatr. 25, 442 (2025).

Lang, J. J. et al. Top 10 international priorities for physical fitness research and surveillance among children and adolescents: A Twin-Panel Delphi study. Sports Med. 53, 549–564 (2023).

Cai, S. et al. Secular trends in physical fitness and cardiovascular risks among Chinese college students: an analysis of five successive National surveys between 2000 and 2019. Lancet Reg. Health-W Pac. 58, 101560 (2025).

Muthuri, S. K. et al. Temporal trends and correlates of physical Activity, sedentary Behaviour, and physical fitness among School-Aged children in Sub-Saharan africa: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 11, 3327–3359 (2014).

Zhao, P., Du, T., Zhou, Q. & Wang, Y. Association of Weight-Adjusted-Waist index with All-Cause and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with diabetes or prediabetes: A cohort study from Nhanes 2005–2018. Sci. Rep. 14, 24061 (2024).

Tao, Z., Zuo, P. & Ma, G. The association between Weight-Adjusted waist circumference index and cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes. Sci. Rep. 14, 18973 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Comparison of novel and traditional anthropometric indices in Eastern-China adults: which is the best indicator of the metabolically obese normal weight phenotype? Bmc Public. Health. 24, 2192 (2024).

Gonzalez-Suarez, C. B. et al. The association of physical fitness with body mass index and waist circumference in Filipino preadolescents. Asia-Pac J. Public. Health. 25, 74–83 (2013).

Li, X. et al. Relationship between Weight-Adjusted waist index (Wwi) and osteoarthritis: A Cross-Sectional study using Nhanes data. Sci. Rep. 14, 28554 (2024).

Sun, P. et al. Sex comparison of the association between Weight-Adjusted waist index and physical fitness index: A Cross-Sectional survey of adolescents in Xinjiang, China. Sci. Rep. 15, 18723 (2025).

Liu, Y., Liang, R., Lin, Y. & Xu, B. The significance of assessing the Weight-Adjusted-Waist index (Wwi) in patients with depression: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 386, 119479 (2025).

Cao, T. et al. Association of Weight-Adjusted waist index with All-Cause mortality among Non-Asian individuals: A National Population-Based cohort study. Nutr. J. 23, 62 (2024).

Whitlock, G. et al. Body-Mass index and Cause-Specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet 373, 1083–1096 (2009).

Liu, H. et al. Association between Weight-Adjusted waist index and depressive symptoms: A nationally representative Cross-Sectional study from Nhanes 2005 to 2018. J. Affect. Disord. 350, 49–57 (2024).

Li, M. et al. The association between Weight-Adjusted-Waist index and depression: results from Nhanes 2005–2018. J. Affect. Disord. 347, 299–305 (2024).

Fei, S. et al. Association between Weight-Adjusted-Waist index and depression: A Cross-Sectional study. Endocr. Connect. 13, e230450 (2024).

Wen, B. et al. [Physical fitness and its regional distribution of Chinese students aged 13 to 18 in 2014]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 40, 616–620 (2019).

Ye, J. et al. Association between the Weight-Adjusted waist index and stroke: A Cross-Sectional study. Bmc Public. Health. 23, 1689 (2023).

CNSSCH Association. Report on the 2019Th National Survey on Students’Constitution and Health (China College & University, 2022).

Haiyun, L. A Comparative Study of 20-Meter Folding Run and 800/1000-Meter Run To Evaluate the Cardiorespiratory Endurance of Secondary School Students (Beijing Sports University, 2019).

Li, X. & Zhou, Q. Relationship of Weight-Adjusted waist index and developmental disabilities in children 6 to 17 years of age: A Cross-Sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1406996 (2024).

Farello, G., Altieri, C., Cutini, M., Pozzobon, G. & Verrotti, A. Review of the literature on current changes in the timing of pubertal development and the incomplete forms of early puberty. Front. Pediatr. 7, 147 (2019).

Uldbjerg, C. S. et al. Prenatal and postnatal exposures to endocrine disrupting chemicals and timing of pubertal onset in girls and boys: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 28, 687–716 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Physical fitness reference standards for Chinese children and adolescents. Sci. Rep. 11, 4991 (2021).

Shalabi, K. M., AlSharif, Z. A., Alrowaishd, S. A. & Al, A. R. Relationship between body mass index and Health-Related physical fitness: A Cross-Sectional study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 27, 9540–9549 (2023).

Chen, G., Chen, J., Liu, J., Hu, Y. & Liu, Y. Relationship between body mass index and physical fitness of children and adolescents in Xinjiang, china: A Cross-Sectional study. Bmc Public. Health. 22, 1680 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Roles of Age, Sex, and weight status in the muscular fitness of Chinese Tibetan children and adolescents living at altitudes over 3600 M: A Cross-Sectional study. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 34, e23624 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Compared with dietary behavior and physical activity risk, sedentary behavior risk is an important factor in overweight and obesity: evidence from a study of children and adolescents aged 13–18 years in Xinjiang, China. Bmc Pediatr. 22, 582 (2022).

Hirschberg, A. L. Female hyperandrogenism and elite sport. Endocr. Connect. 9, R81–R92 (2020).

Lyu, X. et al. Association between the Weight-Adjusted-Waist index and Familial hypercholesterolemia: A Cross-Sectional study. Bmc Cardiovasc. Disord. 24, 632 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. Association between the Weight-Adjusted waist index and Age-Related macular degeneration: results from Nhanes 2005–2008. Med. (Baltim). 104, e42348 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all participants for their support and assistance with our research.

Funding

This research was funded by the “B” category project of the Education Science Plan of Laibin City, China (LBJK2024B130); Sports and Health Industry Research Group (GXKS20204QNTD14).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Data curation, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Formal analysis, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Funding acquisition, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Investigation, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Methodology, Gulnur Ahmat; Project administration, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Resources, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Software, Bingqian Zhang; Supervision, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Validation, Bingqian Zhang; Visualization, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song; Writing—original draft, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song, Gulnur Ahmat, Bingqian Zhang; Writing—review & editing, Shukun Kang, Pengwei Song, Gulnur Ahmat, Bingqian Zhang; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians before the assessment of participants in this study, and participants volunteered to be assessed for this study. Approved by the human ethics committee of Xinjiang Normal University (0894157).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, S., Song, P., Ahmat, G. et al. The association between weight-adjusted waist index and physical fitness index among Chinese adolescents. Sci Rep 16, 1125 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30872-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30872-y