Abstract

This study investigates the influence of concrete’s mesoscopic heterogeneity and internal defects on its mesoscopic mechanical behavior and macroscopic nonlinear response. Using defective concrete as a model system, the research systematically examines the impact of mesoscopic heterogeneity on fracture processes and damage evolution. This is accomplished through an integrated approach combining micro-CT scanning, digital image processing, physical experiments, and numerical simulations. Fractal dimension analysis is then employed to provide an in-depth characterization of mesoscopic damage evolution. It is important to note that the acoustic emission (AE) results discussed are derived from numerical simulations, and the results demonstrate that: (1) The shape, size, and spatial distribution of internal constituents contribute to mesoscopic heterogeneity, which can be effectively quantified using digital image processing techniques. The resulting mesoscopic structural model, when implemented within the RFPA2D (Rock Failure Process Analysis System), provides reliable numerical simulation results. (2) The reduced mechanical strength of the interfacial transition zone between aggregate and mortar matrix severs as a preferential location for crack initiation. Crack initiation and subsequent propagation are preferentially observed in regions of high stress concentration, typically induced by pre-existing cracks and pores. Aggregate particles impede crack propagation, causing deviations in the crack path. The inherent mesoscopic heterogeneity of the material is a fundamental driver of this irregular crack propagation. (3) Analysis of the fractal dimension of the damage zone within the concrete reveals that the fractal dimension increases with applied stress up to the point of peak stress. The fractal dimension reaches its maximum value at the peak stress. The fractal dimension of the undamaged specimen is 1.342, representing the maximum observed value, whereas the specimen containing holes and cracks exhibits a minimum fractal dimension of 1.211. This indicates that the presence of defects such as holes and cracks leads to stress concentration, resulting in a more localized accumulation of failure elements and, consequently, a lower fractal dimension value. (4) The fractal dimension of the damage zone provides a valuable metric for characterizing the internal damage development within concrete. This approach offers a novel perspective for quantitatively investigating the mesoscopic damage mechanism in concrete and establishing a direct link between internal structural modifications and the macroscopic mechanical behavior of the material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concrete is a ubiquitous material in civil engineering and critical for the construction of national infrastructure due to its durability, high compressive strength, and resistance to corrosion. As a manufactured material, concrete is inherently a complex multi-phase composite comprising coarse aggregate, cement, water, fine aggregate, and supplementary cementitious materials1,2. The presence of randomly distributed micro-cracks, air voids, and other heterogeneities at the mesoscale introduces significant complexity to the material’s damage evolution and overall mechanical behavior3,4. Indeed, the evolution of these pre-existing defects under load dictates the macroscopic mechanical properties of concrete. Therefore, understanding and quantitatively characterizing the internal mesostructural changes induced by stress, and establishing a clear link to the macroscopic mechanical response, has been a central focus of research on nonlinear damage, fracture behavior, and constitutive modeling of concrete. This understanding is crucial for addressing practical engineering challenges5,6,7. However, the highly irregular nature of mesoscopic damage evolution in concrete, coupled with a lack of robust quantitative methods for describing these changes, has hindered progress in fully resolving this fundamental problem. Consequently, it remains a significant challenge in the study of concrete damage and failure mechanics8.

The mechanical mechanisms of concrete material failure have attracted the attention of many researchers around the world in recent years and have achieved favorable findings. Currently, investigation on concrete mainly applies traditional mechanical testing methods, which infer structural material stress characteristics through comparative analyses of test data. Concrete internal mesostructure changes cannot be directly employed to describe evolution and failure processes under load9 and it can only reflect macroscopic phenomena; therefore, it is difficult to comprehensively explore the relationships among macroscopic phenomena and internal mechanisms, greatly restricting research on concrete mechanical properties10,11. Since the performance of computers has been significantly enhanced, numerical simulation approaches have made it more straightforward and effective to evaluate concrete failure mechanisms and processes12,13. To study the macroscopic mechanical characteristics and failure processes of concrete under various loading rates. Pedersen et al.14 established a stefan effect-based two-dimensional numerical model. Huang et al.15 applied particle flow numerical simulation software (PFC2D) to evaluate the effects of coarse aggregate on concrete damage progression and macroscopic mechanical characteristics and revealed a positive correlation between the coarse aggregate content and the peak strength of specimen. Zhang et al.16 studied the impacts of ITZ on concrete failure mechanical behavior by using PFC2D software to generate a discrete element numerical model considering concrete ITZ features and developed a numerical method for effectively simulate concrete failures. Wang et al.17 introduced “placement algorithm” and applied it to develop random convex, ellipsoidal and spherical polyhedral aggregate models. They also used cohesive elements to characterize interfaces among mortar, aggregates, and aggregate mortar and nonlinear cohesion laws to numerically simulate concrete crack propagation modes under uniaxial compressive loads. The abovementioned research works have clearly presented concrete material failure mechanical mechanism; however, few studies have explored the effects of the actual mesostructures of the materials on both macroscopic mechanical properties and mesoscopic damage evolution mechanism. Concrete is a common heterogeneous material at mesoscale and conventional numerical simulation approaches have certain limitations for the investigation of concrete damage and failure processes4.

With the progress of computer graphics techniques and hardware in image processing, digital image processing technology has become increasingly prevalent in various fields18. Some researchers have used these technologies to numerically analyze rock mesomechanics and have obtained many favorable outcomes. Yu et al. 19 proposed a digital image processing theory-based digital image-based rock heterogeneity characterization technique and tested it in preliminary applications. From a mesoscopic perspective, Saksala et al. 20 explored the evolution of concrete internal particles during its failure process based on its composition characteristics and internal structural components. They used numerical simulations and particle flow program to obtain cross-scale damage effects from mesoscopic to macroscopic. Liu et al. 21 developed a numerical model combining rock fracture process analysis system (RFPA2D) and digital image processing technique to take into account rock heterogeneity and simulate the initiation and propagation processes of cracks under uniaxial compression. Regarding fractal theory, researchers have performed surface damage fractal analyses on concrete digital images obtained through image processing technology and have derived concrete failure fractal damage evolution law and the constitutive relationships among the influences of different damage variables on concrete22,23. Extensive studies have been conducted on concrete material failure and damage mechanical mechanisms at macroscopic level and have achieved several beneficial results. However, relatively little research has been performed on concrete heterogeneity and its nonlinear characteristics at various phase materials; Therefore, there is a lack of a comprehensive understanding on the fracture of concrete materials under load. Hence, a comprehensive research on the structural properties of the various concrete phase materials at mesoscopic level is essential to comprehensively analyze concrete failure and damage development mechanisms and reveal the correlation between its mesoscopic and macroscopic mechanical behaviors.

To address these limitations, this study focuses on defective concrete, systematically investigating the influence of mesoscopic heterogeneity on its fracture process and damage evolution characteristics. This is achieved through an integrated approach combining micro-CT scanning, digital image processing, physical experiments, and numerical simulation methods. A custom-build calculation program, developed using MATLAB based on the box-counting method, is employed to determine the fractal dimension of mesoscopic damage patterns observed in defective concrete specimens. the resulting fractal dimensions are then used to characterize damage evolution, providing insights into the macroscopic and mesoscopic failure mechanisms of defective concrete materials. The obtained fractal dimensions as well as simulated acoustic emission (AE) data from the developed numerical model are then applied for the characterization of damage evolution, providing insights into defective concrete material macroscopic and mesoscopic failure mechanisms. In addition, the integrated method combining RFPA2D simulations and micro-CT technology provides a valuable reference for other mesoscale modeling frameworks for the simulation of fracture mechanics in quasi-brittle materials such as concrete. For example, integration of lattice discrete particle models (LDPM)38 and micro-CT-derived realistic mesostructural characteristics can remarkably improve the representation of aggregate-mortar matrix interactions, enhancing the accuracy of predicting the initiation and propagation of crack. Similarly, integrating microplane models39 into realistic mesostructural characteristics enables more precise simulation of mesostructural heterogeneity-induced macroscopic nonlinear mechanical behaviors under complex stress states. The numerical and experimental results presented in this research—particularly regarding the sensitivity of crack path to interfacial transition zone (ITZ) properties, pre-existing flaws, and heterogeneity—provide valuable validation data for these alternative methods. Micro-CT-based mesostructural reconstruction and fracture process analyses can be applied for the verification of crack propagation patterns, calibration of model parameters, and enhancement of the predictive accuracy of microplane, LDPM, and other advanced frameworks.

Samples and methods

Specimen preparation

Mix design is a key step in this research, as its rationality directly affects concrete specimen mechanical properties and subsequent experimental results. In this research, concrete specimens were fabricated using materials such as water, fly ash (model: G23v6k53), Portland cement (P·I), crushed stone (limestone), river sand, and water reducing agent (Naphthalene series), and grain size is distributed in two levels: maximum grain size does not exceed 40 mm and coarse aggregate particle size includes 5–20 mm and 20–40 mm. Design mix proportions of the materials are 165 kg/m3 for water, 90 kg/m3 for fly ash, 285 kg/m3 for cement, 1126 kg/m3 for crushed stone, 734 kg/m3 for sand, and 6.75 kg/m3 for water reducing agent. The following basic conditions are considered for specimen curing: curing time 28 days, temperature (20 ± 2)℃, and relative humidity 95%. According to “Rock Physical and Mechanical Properties Test Procedure” (DZ/T 0276–2015) and “Engineering Rock Test Method Standard” (GB/T50266-2013), concrete is made into cubic standard specimens with dimensions of 75 mm × 75 mm in the form of complete concrete specimens (Specimen 1), concrete specimens with holes (Specimen 2), concrete specimens with cracks (Specimen 3), and concrete specimens with cracks and holes (Specimen 4). Specimen errors were smaller than 0.3 mm and upper and lower loading end surface non-parallelism was controlled below 0.05 mm. Specimen axis is perpendicular to the upper and lower end surfaces, with maximum deviation being controlled below 0.25°. Figure 2a shows the specimen.

Experimental methods

Physical test experiment

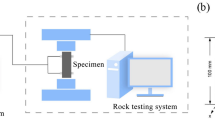

Uniaxial compression tests were performed at the College of Mining, Guizhou University, using an electro-hydraulic servo pressure testing device (HYWE-100060) controlled by a microcomputer (Fig. 1). The testing machine’s loading system, hydraulic proportional system, and microcomputer system are fully digitally controlled. High-precision sensors continuously monitor and record experimental data, including force, displacement, and deformation, which are dynamically displayed as curves by the computer. Testing machine maximum loading force is 1000kN, with piston stroke of 150 mm and indication accuracy of ± 0.5%. Based on GB/T 50,081 − 2002 24, force control is applied for loading at a rate of 0.3 MPa/s. The specimen is placed in a pressure chamber and loaded using a pressure device until it is damaged and reaches the stress peak where the loading is stopped and specimen deformation measurement is completed using YYU-10/50 electronic extensometer.

Micro-CT scanning and digital image characterization

Micro CT scanning was performed at Tianjin Sanying Precision Instrument Co., Ltd., using a nanoVoxel-4000 system (Fig. 2b) to acquire internal structural information from the concrete specimens (Specimens 1–4). The system operates at a voltage of 280 kV and a current of 300 µA, achieving a maximum scanning resolution of 0.5 µm. To obtain high-quality digital images, a concrete sample with a size of approximately 75 mm × 75 mm × 75 mm was scanned by CT, with an actual scanning accuracy of 42.32 µm, and the final scanned slice is shown in Fig. 2c, as shown in the figure, the slices obtained through CT scanning can more clearly reflect the internal structural characteristics of the specimen. The statistics of equivalent pore diameter size are shown in Fig. 3, from the histogram of the number of equivalent pore diameters, it can be seen that the majority of equivalent diameters are greater than 100 and less than 250 μm; From the pie chart of pore volume fraction, it can be seen that the proportion of volume with equivalent diameter greater than 1000 μm is relatively large, about 45.77%.

As a new discipline investigating the theory and application of image, the main goal of digital image processing is converting target objects into digital images, storing them in computers, and obtaining the desired results by image processing in computers. Digital image processing technologies can be employed for the identification and segmentation of various media within a material to obtain an image representing the true mesostructure of the material21,25. This research explores the effects of different flaws (including cracks and holes) on fracture processes and damage development in concrete materials. Figure 2a illustrates a concrete sample prepared in the laboratory, Fig. 2b shows a high-resolution industrial CT (nanoVoxel-4000) from Tianjin Sanying Company, and Fig. 2c presents a 24-bit true color image of a concrete slice acquired through scanning, where dark material is cement mortar, black material is holes and cracks, and bright material is aggregate. The resolution of the image is 500 × 500 pixels. Because of strong color changes in the image, HIS space (H is hue, I is brightness and S is saturation) is applied for the determination of variations in the value of I for threshold segmentation4; Fig. 2c shows the location where the scanning line AA’ crosses the image and Fig. 2d illustrates the fluctuation curve of the value of I on the scanning line AA’. The segmentation thresholds of 90 and 150 were obtained through multiple experiments in Image J software by comparing the variation curve with internal medium of the material through which the scanning line passes. Therefore, three intervals exist where I value can be separated, i.e., 0 ~ 90, 91 ~ 150 and 151 ~ 255 representing pores, mortar matrix, and aggregate, respectively. That is, the internal medium of concrete can be classified into three types. Figure 2e shows the representation image after image processing, where in comparison with Fig. 2c, representation image can present the real structure of concrete.

Establishment of numerical model considering heterogeneity of concrete

Integrating digital image processing with finite element methods requires transforming the segmented image into a discretized mesh with assigned material properties. Since digital images are composed of discrete pixels, each pixel in the image can be directly mapped to a finite element within the numerical model (Fig. 4). The aggregate of these finite elements, each with distinct properties, represents the mesostructured of the concrete, due to the image resolution of 500 × 500 pixels, the entire numerical model can be divided into 500 × 500 mesh, material properties are assigned to each element based on the color (or intensity value) associated with its corresponding pixel in the segmented image. Furthermore, heterogeneity coefficients are assigned to each material phase to account for inherent variability within each phase, resulting in a numerical model that captures the true mesostructure of the concrete. ITZ was not explicitly modeled as a separate phase, but was indirectly presented through spatial heterogeneity in material characteristics assigned to the aggregate and mortar elements21,25. Mesh size was fixed by the resolution of CT image (500 × 500 pixels for a 75 mm specimen) and while a sensitivity evaluation of formal mesh was not conducted, the application of a statistical distribution for properties helps alleviate mesh dependency concerns to simulate fracture in quasi-brittle materials such as concrete26,36.

RFPA2D was employed to conduct concrete uniaxial compression numerical simulation tests. RFPA2D system effectively couples digital image processing and a finite element-based failure analysis framework. It simulates the damage of material by assigning heterogeneous mechanical characteristics to meso-elements according to Weibull distribution, enabling realistic crack initiation and propagation modeling under load26. Each micro-fracture of an element in RFPA2D is considered as an acoustic emission event, cumulative AE count corresponds to the total failed element number, while AE energy is obtained from the released elastic energy during failure. This approach makes quantitative damage evolution tracking possible without physical sensors21,25,34. To consider the effect of concrete material heterogeneity in numerical calculations, it is assumed that the strength and elastic modulus of meso-elements such as mortar matrix, aggregate, and pores obey Weibull distribution27:

where u is the mechanical property characteristics of the meso-element, such as strength and elastic modulus; u0 is the mean value of the mechanical property characteristics of the meso-element; m is material homogeneity, such that increase of homogeneity m results in more uniform material. In the model, the heterogeneity of different mesoscopic media is considered and mesoscopic elements are assigned mechanical parameters using Monte Carlo method28,29.

Table 1 summarizes the mechanical parameters of many mesoscopic media within the concrete4. The numerical model has the dimensions of 75 mm × 75 mm, which is divided into 500 × 500 mesh, each one being a square with a side length of 0.0225 mm, as shown in Fig. 4. Figure 5 illustrates model loading diagram. The entire model is fixed along horizontal direction (X), P is axial pressure exerted on the model, and axial direction displacement compression loading control is applied. The initial displacement is considered as 0.002 mm and loading is performed in 0.002 mm increments one at a time until specimen failure.

This study conducted physical experiments and numerical simulations on the concrete specimens in Fig. 2a, while maintaining the same boundary and control conditions, to demonstrate how various flaws affect the mesoscopic failure mechanisms and macroscopic fracture mechanical characteristics of concrete materials.

Fractal analysis of images using the box-counting method

The concept of fractal dimension, introduced by B.B. Mandelbrot30, has found widespread application across various scientific disciplines in recent years. Studies in materials science, geology, and physics31,32,33,34 have demonstrated that fractal methods can quantitatively describe and differentiate complex, highly asymmetrical forms or behaviors exhibiting statistical self-similarity. This offers a novel approach for quantitatively characterizing irregular damage and failure behavior within concrete. Fractal dimension is a major fractal parameter, which quantitatively describes the fundamental properties of fractal sets. Variations of fractal dimensions not only reflect damage area complexity, but is more fundamentally correlated with energy dissipation distribution pattern and crack network connectivity. Higher fractal dimensions usually mean more dispersed damage and more uniform energy release, while lower fractal dimensions indicate more concentrated damage and energy release and obtaining its value is the key to use fractal concepts to solve practical problems21,23,25. Several methods are available for the calculation of fractal dimension; however, box-counting dimension is straightforward in computing and measuring and can easily represent the level of occupancy in target object in the study area32,34. The aim of this research is to employ box dimension for fractal analysis on the mesoscopic failure elements area of concrete specimens with different defects. Using box dimension theory, damage degree to concrete specimens is determined by calculating the fractal dimension of specimen mesoscopic failure elements area at various stress levels. After the extraction of the acoustic emission images obtained from numerical experiment processes, PCAS software is applied to binarize the acoustic emission evolution images under different stress levels35, and the resulting black and white images can effectively identify damage degree to concrete specimens, as illustrated in Fig. 6 (An evolution diagram of acoustic emission binary image from a failure specimen under different stress levels). Assuming that a square with a side length of b covers a binary image and the number of squares covering the damaged element is N (b), the fractal box dimension Ds of the concrete specimen under a specific stress condition is calculated by continuously changing the size of b and taking the logarithm of N (b) and b and dividing them as:

Based on image storage principles and box-counting theory, a custom material pore and crack image recognition, processing, and fractal dimension calculation system was developed in-house using the MATLAB platform21. The matching fractal dimension can be determined by entering the binary images of acoustic emission evolution under different stress levels in the numerical experiment into the system. The computation procedure is shown in Fig. 7. Figure 8 presents the application of box dimension approach for the determination of the binary image of the fractal dimension of acoustic emission evolution. Figure 8d shows a fractal fitting diagram of specimen failure with cracks and pores at a stress level of 50%, with a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.9887. The damage evolution process of the material is fractal, mesoscopic fracture distribution exhibits good self-similarity, and fractal dimension, with a value of Ds = 1.034, has a high believability degree.

It is noteworthy that the calculated fractal dimension value is not an absolute metric, but is relative and depends on many factors. The obtained value is sensitive to original micro-CT image resolution, the algorithm applied for the generation of acoustic emission event maps, and the selection of threshold during binarization. In addition, fractal analysis in this research is performed on two-dimensional slices. While this provides valuable information regarding damage patterns, it inherently cannot fully capture the three-dimensional damage network spatial complexity within concrete volume. The three-dimensional topological properties of damage may not be completely illustrated in a two-dimensional projection. Hence, the primary value of the fractal dimension in this context lies in its relative trend of change (as shown later in Fig. 14), comparing the evolution laws under different defect types and stress levels, which provides a powerful quantitative basis for understanding the influence of defects on damage modes, rather than relying solely on the absolute value for description.

Results and discussion

Mechanical characteristics analysis of concrete with pores and cracks

Figure 9 illustrates maximum principal stress distribution for specimens 1–4 during initial loading stage, where areas with brighter colors presenting higher stress values. It can be witnessed from the diagram that there is an unequal stress distribution within the specimen and aggregate-mortar matrix contact surface is where the distribution of stress concentration is most significant, i.e., around the hole and at crack tip. Stress distribution is strongly affected by internal flaws in concrete materials (holes and cracks) as well as the heterogeneity caused on by the internal structure of the material.

Figure 10 presents the stress-strain curves obtained from both numerical simulations and physical experiments for the concrete specimens under uniaxial compression. The peak strength varies significantly among specimens with different types of defects. The stress-strain curves exhibit characteristic nonlinear behavior, which can be attributed to the presence of internal defects and the inherent heterogeneity of the concrete. In the initial loading phase, the curves exhibit a linear elastic response. As the load increases, the curves transition to a nonlinear regime until reaching the peak strength. Beyond the peak strength, the curves show a distinct stress drop, indicating post-peak damage. As shown in Fig. 10, the physical experimental stress-strain curve indicates that the peak concrete strength decreases when defects are present. The peak strengths of complete concrete, concrete with holes, concrete with cracks and specimens with holes and cracks are 39.02, 35.06, 31.08 and 23.21 MPa, respectively. Under the absence of defects such as cracks and holes, the peak strength of complete specimen is the highest, while the specimen with cracks and holes is simultaneously influenced by the combined effects of these defects, resulting in the minimum peak strength, with peak stress difference of 15.81 MPa, presenting a reduction of 40.52%, which indicates that concrete macroscopic mechanical characteristics are strongly influenced by material flaws such as cracks and pores. By comparing the stress-strain curves obtained from physical experiments and numerical simulations presented in Fig. 10, specimen peak strengths are in the order of specimen 1 > specimen 2 > specimen 3 > specimen 4. Also, peak strength and curve variation trend exhibit good consistency, indicating that the results obtained from numerical simulation are highly reliable. From Fig. 10, a certain difference is witnessed between the specimen peak strengths obtained from physical experiments and numerical simulations. This is because the numerical model fully considers the effect of heterogeneity due to material internal mesostructure on concrete macroscopic mechanical properties. Different internal mesostructures create differences in stress concentration degree during specimen loading, which induces damage gradually leading to failure. Material mesoscopic heterogeneity is the essential reason for the difference observed between numerical and experimental results. In addition, while incorporating real mesostructure from micro-CT scanning, the numerical model assigns material properties for each phase based on statistical distributions (Weibull distribution). This approach captures mesoscopic heterogeneity, but cannot perfectly replicate the exact property variability at every point in specific physical specimen. At the same time, potential minor imperfections during the preparation and testing of specimens (e.g., strong variations in the alignment of loading platens) can contribute to discrepancies. Relative peak strength percentage differences between simulation and experimental results for Specimens 1 through 4 are about 5.2, 7.1, 8.5, and 6.3%, respectively. These variations are within reasonable ranges and do not detract from the primary finding that both approaches consistently present a significant reduction in strength due to defects, with the combined cracks and holes resulting in the most severe degradation of strength. The key validation of the model lies in its ability to reproduce the mechanical responses and failure mechanisms observed in the laboratory. This reproduction is both relatively accurate and qualitative.

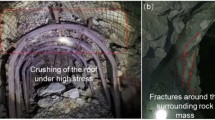

Analysis of crack propagation characteristics and meso-fracture evolution of specimens

Figure 11 illustrates the evolution of acoustic emission (obtained from numerical simulations) and elastic modulus during the failure process of concrete specimens with various defects. In the acoustic emission diagrams, elements experiencing tensile failure in the current loading step are indicated in red, elements experiencing compressive shear failure are indicated in white, and elements that have completely failed are indicated in black. In the complete specimen, cracks initiate along the loading direction within the aggregate boundary and cement mortar, as the local stress in these regions reaches the element damage threshold. These microcracks propagate with increasing load, connecting and penetrating due to the accumulation of tensile failure elements. Axial splitting failure occurs upon complete crack penetration between the upper and lower ends of the specimen. This failure mode closely aligns with the final failure mode observed in the physical experiments. Initial cracks initiate perpendicular to the upper and lower edges of the hole, and steadily propagate with increasing axial stress. Simultaneously, microcracks initiate and propagate rapidly along the aggregate-mortar matrix interface (weak surface). Macroscopic cracks develop and propagate along this weak surface on the right side of the specimen, resulting from coalescence of tensile failure elements. The high mechanical strength of the aggregates impedes crack propagation around the pores to some extent. The eventual penetration of cracks on the upper right and lower left sides of the specimen leads to instability and tensile splitting failure, with a final fracture morphology highly consistent with that observed in the physical experiments. Cracks initiate at the tip of pre-existing crack and propagate perpendicularly to it, due to stress concentrations reaching the element damage threshold. Small fissures also initiate on the right and left sides of the pre-existing crack at the interface between cement mortar and aggregate, and then spread axially. With increasing stress, the crack encounters aggregates and expands along their boundaries. The crack on the left side of the pre-existing crack penetrates the upper end surface of the specimen, while the crack on the right side penetrates the lower end surface. Penetration of prefabricated cracks leads to a macroscopic failure surface and splitting failure, consistent with the physical experiments. Cracks initiate perpendicular to the tip of the pre-existing crack and expand steadily. As stress continues to increase, the crack at the lower end penetrates the aggregate, creating a transgranular crack, while the crack at the upper end continues to expand along the weak surface. Macroscopic cracks develop on the right side of the specimen and spread throughout the weak surface due to the accumulation of tensile failure elements. These fissures penetrate the specimen’s upper and lower end faces, forming macroscopic fractures, ultimately leading to specimen failure and instability. This experimental phenomenon is consistent with the results obtained from physical experiments.

The acoustic emission evolution diagram presented in Fig. 11 shows that the internal failure elements of the specimen primarily include tensile failure (red) and causes of macroscopic shear band formation are the accumulation and connection of tensile failure elements within the specimen. The mesoscopic heterogeneity due to concrete internal structure as well as the presence of cracks and pores, strongly influence the ultimate failure mode and fracture propagation path of the concrete. Due to the low mechanical strength of the interface between mortar matrix and aggregates, it is generally the main location for the induction of crack initiation. Prefabricated holes and cracks are generally the main crack initiation and expansion paths under stress concentration. Simultaneously, the high-strength mechanical characteristics of aggregates can block crack propagation, modifying crack propagation path, ultimately affecting the macroscopic failure mode of the specimen. Concrete macroscopic failure mode is strongly affected by its intrinsic defects and aggregates have an inhibitory impact on the initiation and propagation of crack, material mesoscopic heterogeneity is the essential reason for irregular crack propagation path.

The law of energy change in the process of damage evolution

Localized stress concentration phenomena in brittle materials are considered as “acoustic emission” and energy is rapidly released and transient elastic waves are generated. Fundamental material damage evolution mechanism includes the application of dissipated energy to induce damage, resulting in strength loss and the quick breakdown of the material is caused by elastic energy release stored in material elements. RFPA2D can be applied to simulated acoustic emission activities36,37. In the developed model, the micro-fracture of an element corresponds to an acoustic emission event, or as AE count, and total acoustic emission event number, indicating that the total number of microfractures in each element is cumulative AE count25. Therefore, the number of failure elements and associated energy release can be employed to explore energy evolution law throughout the failure process of the material.

Figure 12 presents the trends of cumulative AE count, AE count, and stress as a function of loading steps for concrete specimens with various defects. As the number of loading steps increases, the stress rises linearly, followed by a significant stress drop upon reaching the specimen’s peak strength, although some residual strength remains. During the initial loading stage, damage and compaction occur within each specimen, representing an energy accumulation period. The cumulative AE energy and AE count remain near zero, indicating minimal element damage. With increasing load, crack initiation and accumulation occur in localized regions, releasing energy internally and increasing the intensity of the acoustic emission signals. As the specimen approaches its maximum load, the number of damaged elements increases significantly, leading to a rapid increase in acoustic emission events and a strong AE signal. The released elastic energy intensifies crack evolution, indicating that the specimen is approaching failure. Comparing and analyzing Fig. 12a - d, the energy release process during the initiation and propagation of new cracks varies depending on mesostructural conditions, resulting in different acoustic emission responses during failure. Following the concentrated occurrence of acoustic emission, the cumulative frequency curve of acoustic emission increases linearly with increasing load. After the load-bearing capacity of the specimen reaches its peak strength and enters the post-fracture stage, the acoustic emission phenomenon does not immediately diminish, and numerous acoustic emission events continue to occur. Eventually, the rate of acoustic emission occurrences gradually approaches zero as the cracks interconnect to form a macroscopic failure surface, and the specimen undergoes complete failure.

Fractal characteristics based on box dimensions of acoustic emission field

To investigate the fractal properties of various defects on concrete material mesoscopic fracture evolution, this section quantitatively characterizes concrete specimen mesoscopic fracture damage evolution process by combining image fractal analysis (Sect. 2.4). Binary acoustic emission evolution images under various stress levels in numerical experiments were imported into a self-developed fractal dimension calculation and material pore crack image recognition system for calculation. Table 2 summarizes the calculation results of the fractal dimension and acoustic emission energy of defective concrete specimens under different stress levels.

Figure 13 illustrates the correlation between acoustic emission energy and stress level for concrete specimens with various defects. As the stress level increases, the acoustic emission energy of each specimen also increases, reflecting the progressive increase in the number and length of cracks and the growing number of internal failure elements. This indicates that the damage evolution process under various stress conditions is characterized by accelerated degradation. When the stress level is below 90%, the acoustic emission energy changes tend to be gradual and exhibit a near-linear increase. However, when the stress level exceeds 90%, approaching the peak strength, the acoustic emission energy increases rapidly and reaches a peak, resulting from the failure of numerous elements and the release of significant amounts of energy. This leads to rapid expansion and penetration of cracks, generating a macroscopic failure zone (Fig. 11). The complete specimen (specimen 1) releases the greatest amount of acoustic emission energy at the point of maximum stress. Consistent with the acoustic emission evolution patterns shown in Fig. 11, this suggests that the macroscopic failure and internal damage are most severe in this specimen. This is because the absence of pre-existing defects, such as holes and cracks, leads to a more dispersed distribution of damage elements throughout the specimen, requiring more energy to be released during failure. Conversely, specimen 4, containing both holes and cracks, exhibits the smallest acoustic emission energy value, indicating a less severe degree of internal damage.

Figure 14 illustrates the correlation between the applied stress level and the fractal dimension Ds of mesostructural fracture damage evolution in concrete specimens with various defects. As the stress level increases, the fractal dimension of all specimens generally exhibits an increasing trend. This increase in fractal dimension reflects the progressive increase in internal fracture elements within the specimen (Fig. 6), demonstrating a synchronous relationship between stress and damage accumulation.

During the initial loading stage (stress level = 10%), the concrete specimen remains primarily in an elastic compression state, representing an energy accumulation period. Consistent with this, the fractal dimension and AE count remain near zero, indicating minimal element damage. With further increase of stress, the number of fracture elements inside the concrete specimen is increased, increasing damage and generating cracks, ultimately pushing failure into plastic deformation stage (stress level = 20%). Fractal dimension of each specimen is rapidly increased with obvious increase rate. Among them, the fractal dimension of specimens with cracks and holes is generally higher than those of other specimens, indicating that the existence of cracks and holes in early loading stage has the strongest effect on specimen damage. Finally, as stress reaches its peak value (stress level = 100%), the fractal dimension value of the complete specimen is 1.342, which is the maximum value, while the specimen with holes and cracks has a fractal dimension value of 1.211, which is the minimum value. This reveals that the existence of defects such as cracks and holes results in concentrated stress distribution, giving rise to fracture element accumulation inside the specimen, leading to the smallest fractal dimension value. Since the complete specimen is not affected by defects, the generated fracture elements are scattered throughout the specimen, resulting in the largest fractal dimension value.

Prior to reaching peak stress, concrete cracks are typically sparse, short, and relatively evenly distributed. Upon reaching the maximum stress level, however, some of these cracks coalesce and interconnect, forming a limited number of dominant cracks that propagate under the applied load. This propagation of dominant cracks is accompanied by the continued growth of existing microcracks and the initiation of new, branching microcracks, resulting in a significantly increased crack length and density throughout the concrete. After exceeding the peak stress, a relatively long and wide main crack is created in the concrete which fully absorbs and consumes the external force work, causing the main crack to continue to propagate forward. The remaining cracks almost no longer change and crack distribution and evolution in concrete exhibit concentrated localized behavior. The fractal dimension variation trend presented in Fig. 14 intuitively presents crack evolution pattern from simple to complex and then to concentrated and directional development.

As shown in Fig. 14, successful application of fractal dimension in characterizing damage evolution presents its application as a quantitative metric. However, it is essential to consider the limitations discussed in Sect. 2.4. The absolute values of Ds are relative and sensitive to image processing parameters. The main strong point of this research lies in the consistent trend observed across specimens, robustly indicating how different types of defect affect damage complexity and distribution. The lower fractal dimension for specimens with cracks and holes quantitatively confirms the visually-observed more localized and concentrated damage pattern, correlating the meso-structural impact of defects to a macroscopic quantitative parameter. Future work involving 3D fractal analysis using micro-CT reconstructions will provide a more comprehensive characterization.

Hence, concrete internal damage development behavior can be well characterized by damage region fractal dimension offering new ideas on quantitative investigation of mesoscopic damage mechanisms within concrete and determination of the relation of internal structural alterations to material macroscopic mechanical response.

Conclusions

-

(1)

Micro-CT scanning was used to characterize the internal mesostructure of defective concrete. Digital image processing techniques were then applied to quantify the mesoscopic heterogeneity arising from the size, shape, and spatial distribution of internal constituents. A realistic mesostructural numerical model of defective concrete was developed using RFPA2D (Rock Fracture Process Analysis System) in conjunction with finite element mapping principles. Close qualitative agreement between numerical and experimental results for tested specimens validates the reliability of the developed numerical method to explore concrete failure mechanical mechanisms. This provides an effective and convenient approach to probe mesoscopic failure processes regarding its predictive accuracy for a general specimen population would benefit from further statistical analyses with a larger experimental dataset in future work.

-

(2)

Numerical simulations reveal that the accumulation and interconnection of internal tensile failure elements are key drivers of macroscopic shear band formation. Both the inherent mesoscopic heterogeneity of concrete and the presence of pre-existing holes and cracks significantly influence the crack propagation path and ultimate failure mode. The relatively low mechanical strength of the aggregate-mortar matrix interface promotes crack initiation, while pre-existing cracks and holes act as stress concentrators, further facilitating crack initiation and propagation. Aggregates impede crack propagation, causing deviations in the crack path. The resulting irregular crack propagation paths and macroscopic failure modes are consistent with the experimental observations, highlighting the essential role of mesoscopic heterogeneity in concrete failure.

-

(3)

The fractal dimension of the damage region within concrete increases with with stress prior to reaching the peak stress. At peak stress, the complete specimen exhibits the highest fractal dimension (1.342), while the specimen containing holes and cracks exhibits the lowest fractal dimension (1.211). This indicates that defects such as holes and cracks lead to a more concentrated distribution of stress and fracture elements, resulting in a lower fractal dimension. In contrast, the absence of such defects in the complete specimen leads to a more dispersed distribution of fracture elements, resulting in a higher fractal dimension. The fractal dimension of the damage region therefore provides a valuable metric for characterizing the internal damage development behavior of concrete, offering a novel approach for quantitatively investigating mesoscopic damage mechanisms and linking internal structural alterations to macroscopic mechanical response.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or codes generated or used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

References

Bangash, M. Y. H. Concrete and concrete structures: Numerical modelling and applications, (1989).

Neville, A. M. & Brooks, J. J. Concrete technology. (Longman Scientific & Technical, 1987).

Yu, Q., Liu, H., Yang, T. & Liu, H. 3D numerical study on fracture process of concrete with different ITZ properties using X-ray computerized tomography. Int. J. Solids Struct. 147, 204–222 (2018).

Zheng, L. et al. Fractal study on the failure evolution of concrete material with single flaw based on DIP technique. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1–15 (2022). (2022).

Antonaci, P., Bruno, C. L. E., Gliozzi, A. S. & Scalerandi, M. Monitoring evolution of compressive damage in concrete with linear and nonlinear ultrasonic methods. Cem. Concr Res. 40, 1106–1113 (2010).

Hanif, M. U., Ibrahim, Z., Ghaedi, K., Hashim, H. & Javanmardi, A. Damage assessment of reinforced concrete structures using a model-based nonlinear approach – a comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 192, 846–865 (2018).

Basu, S., Thirumalaiselvi, A., Sasmal, S. & Kundu, T. Nonlinear ultrasonics-based technique for monitoring damage progression in reinforced concrete structures. Ultrasonics 115, 106472 (2021).

Massone, L. M., Bedecarratz, E., Rojas, F. & Lafontaine, M. Nonlinear modeling of a damaged reinforced concrete Building and design improvement behavior. J. Build. Eng. 41, 102766 (2021).

Liu, J., Jiang, R., Sun, J., Shi, P. & Yang, Y. Concrete damage evolution and three-dimensional reconstruction by integrating CT test and fractal theory. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 29, 04017122 (2017).

Sun, Z. & Xu, Q. Microscopic, physical and mechanical analysis of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 527, 198–204 (2009).

Liu, Q., Xiao, J. & Sun, Z. Experimental study on the failure mechanism of recycled concrete. Cem. Concr Res. 41, 1050–1057 (2011).

Lian, C., Zhuge, Y. & Beecham, S. Numerical simulation of the mechanical behaviour of porous concrete. Eng. Comput. 28, 984–1002 (2011).

Roussel, N., Spangenberg, J., Wallevik, J. & Wolfs, R. Numerical simulations of concrete processing: from standard formative casting to additive manufacturing. Cem. Concr Res. 135, 106075 (2020).

Pedersen, R. R., Simone, A. & Sluys, L. J. Mesoscopic modeling and simulation of the dynamic tensile behavior of concrete. Cem. Concr Res. 50, 74–87 (2013).

Huang, P., Pan, X., Niu, Y. & Du, L. Concrete failure simulation method based on discrete element method. Eng. Fail. Anal. 139, 106505 (2022).

Zhang, S., Zhang, C., Liao, L. & Wang, C. Numerical study of the effect of ITZ on the failure behaviour of concrete by using particle element modelling. Constr. Build. Mater. 170, 776–789 (2018).

Wang, X., Zhang, M. & Jivkov, A. P. Computational technology for analysis of 3D meso-structure effects on damage and failure of concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 80, 310–333 (2016).

Jähne, B. Digital Image processing[M] (Springer Science & Business Media, 2005).

Yu, Q., Zhu, W., Tang, C. & Yang, T. Impact of rock microstructures on failure processes - numerical study based on DIP technique. Geomech. Eng. 7, 375–401 (2014).

Saksala, T. Numerical modelling of concrete fracture processes under dynamic loading: Meso-mechanical approach based on embedded discontinuity finite elements. Eng. Fract. Mech. 201, 282–297 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Fractal analysis of mesoscale failure evolution and microstructure characterization for sandstone using DIP, SEM-EDS, and micro-CT. Int. J. Geomech. 21, 04021153 (2021).

Carpinteri, A., Lacidogna, G. & Niccolini, G. Fractal analysis of damage detected in concrete structural elements under loading. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 42, 2047–2056 (2009).

Jin, Z. et al. Fractal dimension analysis of concrete specimens under different strain rates. J. Build. Eng. 76, 107044 (2023).

GB/T 50081 – 2002. Standard for test methods for mechanical properties of ordinary concrete. (China Construction Industry, 2002). (in Chinese).

Wu, Z. et al. Numerical simulation and fractal analysis of mesoscopic scale failure in shale using digital images. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 145, 592–599 (2016).

Tang, C. Numerical simulation of progressive rock failure and associated seismicity. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 34, 249–261 (1997).

Weibull, W. A statistical distribution function of wide applicability. J. Appl. Mech. 18 (3), 293–297 (1951).

Rossi, F., Ragazzi, S., Carlo, A. D. & Lugli, P. A generalized Monte Carlo approach for the analysis ofQuantum-transport phenomena in mesoscopic systems:interplay between coherence and relaxation. VLSI Des. 8, 197–202 (1998).

Rubinstein, R. Y. & Kroese, D. P. Simulation and the Monte Carlo Method. 707 (John Wiley & Sons, United States of America, 2011).

Mandelbrot, B. B. Self-affine fractals and fractal dimension. Phys. Scr. 32, 257–260 (1985).

Xie, H. An Introduction To Fractal - Rock Mechanics (Science, 1996). (in Chinese).

Xie, H. P. Fractals in Rock Mechanics (A A Balkema, 1993).

Liu, H. et al. Fractal dimension used as a proxy to understand the Spatial distribution for carlin-type gold deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 158, 105534 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Fractal study on mesodamage evolution of three-dimensional irregular fissured sandstone. Int. J. Geomech. 23, 04023199 (2023).

Liu, C., Tang, C. S., Shi, B. & Suo, W. B. Automatic quantification of crack patterns by image processing. Comput. Geosci. 57, 77–80 (2013).

Tang, C. A., Liu, H., Lee, P. K. K., Tsui, Y. & Tham, L. G. Numerical studies of the influence of microstructure on rock failure in uniaxial compression — part I: effect of heterogeneity. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 37, 555–569 (2000).

Tang, C. A., Xu, X. H., Kou, S. Q., Lindqvist, P. A. & Liu, H. Y. Numerical investigation of particle breakage as applied to mechanical crushing—part I: Single-particle breakage. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 38, 1147–1162 (2001).

Cusatis, G., Pelessone, D. & Mencarelli, A. Lattice discrete particle model (LDPM) for failure behavior of concrete. I: Theory Cement Concrete Comp. 33, 881–890 (2011).

Aguilar, M., Baktheer, A. & Chudoba, R. Multi-axial fatigue of high-strength concrete: Model-enabled interpretation of punch-through shear test response. Eng. Fract. Mech. 311, 110532 (2024).

Funding

This study was supported by the Guizhou Province Science and Technology Plan Project (No.Qian Ke He Basic-[2024] Youth 013); the Liupanshui Normal University high-level talent scientific research start-up project (LPSSYKYJJ202320); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52164006); the Natural Science Foundation of Guizhou Province (Grant No. ZK [2022]533); the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Department (Qian Ke He Zhi Cheng [2022] General 248); the Guizhou Provincial of Social Funding Projects (LDLFJSFW2024-9).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Bo Lv: Writing-original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Result analysis. Hao Liu: Project administration, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. Lulin Zheng: Resources, Investment, Formal analysis. Yujun Zuo: Writing-review & editing, Software. Siyou Xiao: Project administration, Data Curation and analysis. Yanfen Wang: Validation. Tengyuan Zhang: Writing-review & editing. Yong Yang: Investigation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, B., Liu, H., Zheng, L. et al. Study on the mesoscopic failure and fractal characteristics of concrete with holes and cracks. Sci Rep 16, 1219 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30891-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30891-9