Abstract

This study investigates the influence of particle gradation on the shear behavior and particle breakage at the interface between calcareous sand and structural materials (concrete, aluminum alloy, and steel piles) using a self-developed large-scale interface shear apparatus. An enhanced two-parameter gradation equation was proposed to unify the representation of both uniform grading curves and continuous grading curves, incorporating a novel gradation index (Sm) to quantitatively evaluate gradation effects. The results demonstrate that increasing coarse particle content reduces both peak and residual shear stresses while intensifying particle breakage, with these effects being more pronounced under higher normal stresses. Finer gradations exhibited greater softening behavior (βs = 47.66–54.98%), and surface roughness dominated shear strength (concrete > aluminum alloy > steel piles). Friction coefficients decreased with coarser gradations due to modified particle-structure interlocking, following a power-law relationship for shear strength. The proposed Sm index effectively unified continuous and discontinuous gradation characterization, showing exponential correlation with friction coefficients and linear relationship with breakage rates. These findings provide fundamental insights into granular-structure interactions and establish a predictive framework applicable to diverse engineering scenarios, including offshore foundations and extraterrestrial soil-structure systems. The study advances interfacial mechanics through its quantitative gradation approach while offering practical tools for geotechnical design optimization in particle-sensitive environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The calcareous sand region involves numerous infrastructure construction and development issues, such as the construction of port engineering in calcareous sand areas, the development of airport facilities, and the protection of calcareous sand coastlines1,2,3,4,5,6,7. It is not difficult to observe that during the construction of these island and reef projects, the interactions between calcareous sand and structures is involved, and the in-depth research on the mechanical properties of the interface is an important part of calcareous sand and structure interaction.

At present, the research on the mechanical properties of the calcareous sand-structure interface mainly involves factors such as roughness8,9,10,11, structural material8,9,12, particle size13,14,15,16,17, and particle breakage11,12,18,19,20. Research on the influence of gradation on the mechanical properties of interface is relatively scarce. However, existing studies21,22,23,24,25,26,27 have shown that soils with different gradations exhibit significant differences in engineering properties, which have a considerable impact on the mechanical properties of interface. Therefore, it is of great significance to explore the influence of gradation on the mechanical properties of the calcareous sand-structure interface.

Overall, the existing literature contains limited research on the impact of soil gradation on the shear strength of soil-structure interface. Uesugi and Kishida23 characterized various gradation sands using the uniformity coefficient (Cu) and discovered that the impact of gradation on the interfacial strength is minimal. However, this conclusion is subject to limitations. Primarily, the test utilized sand with only two gradations, and the relative roughness of the sand and the corresponding steel plate ranged from 0.006 to 0.03, which is significantly below the critical relative roughness (0.1–0.18). Kim and Ha28 conducted an analysis of the interfacial shear strength between three parallel graded coarse-grained soils and geogrids, discovering that the interface friction coefficient decreased as the maximum particle size increased. Liang et al.29 studied the influence of the gradation distribution of gravel sandstone and mudstone mixed soil on the shear behavior of the soil-steel interface and found that the peak interfacial friction angle decreased linearly with the increase of characteristic particle sizes (d10, d30, d50, d60). Wang et al.24 discovered a linear decrease in both the peak and residual interfacial friction angles with an increase in the Cu through the direct shear test of Fujian sand-steel interfaces with five gradations (where d50 is the same but Cu is different).

From the aforementioned research, it is evident that scholars primarily utilize single characteristic particle sizes (d10, d30, d50, d60) or the coefficient of uniformity (Cu) or coefficient of curvature (Cc) to delineate gradation differences when examining the impact of gradation on interfacial shear behavior. However, Cu and Cc, which can only quantify the width and continuity of the gradation distribution, fall short in describing the micro-scale arrangement among the various components. Consequently, sands with identical Cu and Cc values can exhibit differing gradations24. Similarly, even with an identical single characteristic particle size, the gradation curve may still vary28. Therefore, neither Cu and Cc nor a single characteristic particle size can uniquely characterize the gradation curve, rendering the aforementioned research conclusions challenging to generalize to other engineering situations.

Consequently, it is imperative to identify a method capable of quantitatively and precisely representing the grading and subsequently quantifying the influence of grading on the mechanical properties of interface. Talbot and Richart30, Swamee and Ojha31, Zhu et al. 201832, Zhu et al.33, and Wu et al.25,26 have all contributed extensively to the research on soil grading equations, concluding that it represents a superior approach. In the literature reviewed by Zhu et al.32, the shapes of numerous soil gradation curves were analyzed and summarized into two primary types: hyperbolic and inverse S-shaped. The fractal gradation equation, as proposed by Talbot and Richart30 and others, is limited to describing hyperbolic gradation curves. Zhu et al.32, Zhu et al.33, and Wu et al.25,26 can describe both hyperbolic and inverse S-shaped gradation curves, but their applicability is primarily confined to continuous grading curves and excludes uniformly graded soils. However, as noted by Zhang et al.34 and Dong et al.35, even uniformly graded soils require gradation analysis to establish baseline mechanical behavior (e.g., peak friction angle dependency on particle uniformity). For pile-soil interface shear, Liu and Lehane36 demonstrated that uniform sands exhibit distinct dilatancy effects compared to well-graded soils, necessitating gradation curve documentation. Therefore, constructing a gradation equation capable of uniformly describing both uniform grading curves and continuous grading curves is crucial for quantitatively assessing the impact of gradation on mechanical behavior of soil and soil-structure interface.

Through interface shear tests, we investigated the impact of grading on the properties of the calcareous sand-structure interface and particle breakage. Subsequently, utilizing the two-parameter grading equation proposed by Zhu et al.32, we developed a novel equation capable of uniformly describing both uniform grading curves and continuous grading curves. Additionally, we formulated a new grading index based on this equation. Ultimately, we examined the correlation between the friction coefficient and particle breakage rate with this newly established grading index.

Laboratory tests

Test soils

Calcareous sand is a unique type of sand characterized primarily by its CaCO3 content. It consists primarily of calcareous fragments, marine algae, and shellfish remains. Owing to its irregular shape, pronounced angularity, and extensive internal pore structure, calcareous sand is more susceptible to fragmentation than other terrigenous siliceous sands, experiencing measurable particle breakage at low stress levels, as shown in Fig. 1. Calcareous sand displays spindle-shaped, flaky, and granular morphologies, distinguished by a high degree of angularity, porosity (including internal voids), and irregular shapes. The angularity coefficient (Ag) of carbonate sand ranges between 0.8 and 1.2, while the statistical values for particle roughness (γ) lie between 0.9 and 1.1. In contrast, the statistical values for sphericity (S) and overall contour coefficient (α) exhibit greater dispersion. The primary chemical constituents of calcareous sand were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF), As shown in Table 1.

Based on the statistical analysis of the original particle size distribution curve of calcareous sand in existing practical engineering projects, four gradation curves were designed with the content of coarse particles (2 ~ 5 mm) of 100%,50%,15% and 5% respectively. Particles in the range of 2–5 mm were classified as the coarse fraction. This classification is consistent with the practical application of the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS) and is specifically justified by the fact that particles above 2 mm are the primary contributors to the particle crushing behavior and shear strength characteristics under investigation12,14. The particle size distribution curves are shown in Fig. 2. The basic physical parameters of the grading curves are presented in Table 2.

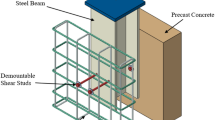

Test pile

The model piles are concrete piles (4C0), steel piles (3S0) and aluminum alloy piles (3A0) with diameters of 4 cm, 3 cm and 3 cm, respectively. The concrete pile is made of C60 high-strength self-compacting concrete. In order to obtain the smooth surface and verticality of the concrete pile, the split seamless steel pipe polished on the inner surface is used as the mold, and the rebars with a diameter of 12 mm and a length of 120 cm are used as the main reinforcements. The concrete is poured slowly at a constant speed and the concrete is compacted by tapping the outside of the mold with a rubber hammer. The aluminum alloy pile is made of 6061 aluminum alloy tube, and it is sandblasted and oxidized. The sandblasting model is 40 mesh emery. The steel pile is made of 45# steel optical axis with good surface finish and linearity. The roughness treatment methods and basic properties of the test pile surfaces are shown in Table 3.

In this paper, the surface roughness of piles was measured using a surface roughness tester of the TR200 model with a moving speed of 0.1 mm/s and was calculated using the arithmetic mean deviation of the profile, Ra. The calculation formula for Ra is as follows:

where, L represents the length of the sample, and z represents the absolute height of the profile distance from the mean line.To ensure accurate measurements, two measurements were taken at different positions along the pile circumference, and three measurements were taken along the length of the pile with each length of 15 mm. The results obtained from the tester are presented in Table3. Photographs of the 3 test piles are shown in Fig. 3.

Test apparatus

The experimental device utilized in this study is a large-scale interface shear apparatus37, which overcomes several limitations of conventional devices. Key improvements include a well-defined normal load direction, a constant interface area during shearing, and adaptable specimen dimensions. The apparatus is equipped with a 20 kN capacity force sensor (accuracy: 0.01 kN) for direct shear force measurement and a 10 cm range displacement sensor (accuracy: 0.001 cm) for displacement monitoring. The dimensions of the specimen used in this study are 66.8 cm × 25 cm. A schematic diagram of the interface shear apparatus is shown in Fig. 4.

Test procedure

The experimental operation primarily involves the following steps: Initially, the model pile is securely affixed in a vertical position, utilizing a limiting bearing. Subsequently, sand is gradually introduced in layers via an air pluviation method device38. Concurrently, normal loads are incrementally applied at a rate of 25 kPa per increment, mediated by an air compressor through the inlet hole. The precise control of normal stress on the pile surface has been calibrated through sand calibration tests. Upon achieving the designated normal stress, this stress level is sustained to accomplish pre-compression. Once pre-compression is successfully concluded, interface shearing is executed through a precision servo control system. Our pre-experimental tests evaluated the shear stress–shear displacement curves at termination displacements of 45 mm, 60 mm, and 90 mm. The results revealed that the difference in residual values was only 1.33% when shearing to 60 mm and 90 mm. This suggests that the strength has largely stabilized at a shear displacement of 60 mm. Therefore, the pre-compression duration was set to 90 min and the shear displacement attained was 60 mm. This study aims to investigate the influence of gradation on interfacial friction characteristics. To ensure the correctness of the experimental laws obtained in this paper, we also added a set of repeated tests, using concrete pile 3C0, normal stress σn = 50, 200 kPa. Only used to ensure that all pile types exhibit the same pattern. The detailed experimental protocol is outlined in Table 4.

Results of repeated experiments

The results of the repeatability tests in this paper are only used to demonstrate the experimental laws, ensure the accuracy of law summarization and the reliability of the gradation equation establishment. The experimental results are not analyzed.

Test results

Stress-displacement curves

The shear stress–shear displacement curves of calcareous sand-concrete piles, with varying gradations and subjected to normal stresses of 50 kPa, 100 kPa, 150 kPa, and 200 kPa, demonstrate a softening trend, as illustrated in Fig. 6. As the coarse particle size content (2 ~5 mm) increases from sand 4# to sand 1#, the initial shear modulus, peak shear stress, and residual shear stress of the interface decrease progressively. Additionally, an increase in normal stress results in an augmentation of both peak shear stress and residual shear stress.

When the normal stresses are 50 kPa, 100 kPa, 150 kPa, and 200 kPa, respectively, the residual values for sand #1 are 15.54 kPa, 29.45 kPa, 42.47 kPa, and 49.13 kPa, and the peak values are 32.01 kPa, 58.81 kPa, 81.15 kPa, and 106.78 kPa, respectively. Compared to sand #1, sand #4 exhibits increases in residual values by 19.27%, 24.56%, 28.72%, and 47.74%, respectively, and in peak values by 33.78%, 37.45%, 49.63%, and 50.29%, respectively. The increases in peak values are consistently higher than those in residual values, suggesting that grading differences have a greater influence on peak values than on residual values. Additionally, as the normal stress increases, the impact of grading differences on both peak and residual values gradually intensifies.

The friction strength of the interface depends to a large extent on the interlocking effect of sand particles and contact materials, which in turn depends on the relative size of sand particles and structural surface roughness. The normalized roughness Rn = Rmax/d50 defined by Uesugi and Kishida23 was introduced to represent the relative roughness of soil and structure, but need to be slightly modified as Rn = Ra/d5039, where Rmax is the vertical maximum peak‒valley distance and d50 is the average particle size. Normalized roughness Rn is a measure of the relative surface roughness with respect to the particle size. For the four graded calcareous sands (1 ~4#) in this paper, the corresponding median particle sizes d50 are 3.5 mm, 2 mm, 0.52 mm and 0.4 mm, respectively. The relative roughness Rn corresponding to the four graded sands can be calculated: 0.01, 0.02, 0.09, 0.12. Compared with the other three graded sands, sand 4# has the smallest median particle size and the largest relative roughness of 0.12, which can be more closely bonded with concrete piles, so it has the highest interfacial friction strength. For sand 3#, 2# and 1#, the median particle size d50 increases continuously, the relative roughness decreases continuously, and the average size of soil particles decreases gradually with respect to the pits or protrusions on the surface of concrete piles. Therefore, the macroscopic performance is that the friction strength is reduced.

The softening coefficient βs is defined to describe the attenuation characteristics of shear strength, and its expression is as follows:

where τp and τr denote the peak and residual shear strengths, respectively. An increase in βs signifies a pronounced disparity between the peak and residual values, thereby leading to a more considerable attenuation in strength. From Fig. 5, it is also evident that, within the normal stress range studied in this paper, the attenuation characteristics of various grades range between 47.66 and 54.98%. The general trend observed is that as the content of coarse particle size (2 ~5 mm) decreases, the softening degree increases.

The test results of sand 3# and 4# with steel smooth pile (3S0) and aluminum alloy pile (3A0) are presented in Fig. 6. The shear stress–shear displacement curves of steel piles generally exhibit a primarily hardening trend or slight softening. However, aluminum alloy piles display a hardening behavior at a normal stress of 50 kPa, whereas they exhibit softening characteristics at higher normal stresses ranging from 100 to 200 kPa. In addition, when the normal stress is 200 kPa, with the increase of shear displacement, the shear stress decreases rapidly after reaching the peak and then increases slightly.

The irregularity observed in the shear stress–shear displacement curve for the aluminum alloy pile at 200 kPa is attributed to the competing mechanisms of particle crushing and interface wear. Under this high normal stress, the initial peak corresponds to the maximum resistance of the coral sand skeleton, followed by rapid softening due to sudden particle crushing near the interface. The subsequent slight regain in shear stress is explained by the exposed, rougher aluminum surface after initial wear, which engages with the newly formed finer particles from crushing. This creates a denser, interlocked shear zone that enhances post-crushing resistance. This phenomenon has been similarly reported in studies on crushable granular materials (e.g.,11,16).

A comparison of Figs. 6 and 7 reveals that, for both aluminum alloy piles and steel piles, the shear strength of sand #4 is greater than that of sand #3, which aligns with the test results obtained for concrete piles. This comparative trend, observed at 200 kPa, remains consistent across all normal stress levels investigated (50–200 kPa), with Sand #4 consistently demonstrating higher peak shear strength than Sand #3 for all pile materials. Using a normal stress of 200 kPa as an illustration, this study compares the peak shear strength differences among three pile types-concrete piles, steel piles, and aluminum alloy piles—in both sand 4# and sand 3#. Overall, the peak values and degrees of softening at the interfaces between aluminum alloy piles and steel piles with various graded soils are relatively small, and the shear displacements required to reach these peak values are also minimal. This is primarily attributed to the smooth surfaces of the aluminum alloy piles and steel piles, which make it difficult for sand particles to generate interlocking friction with these smooth surfaces. During the shearing process, sliding primarily occurs between them, leading to the rapid formation of a stable shear failure surface. Among these, concrete piles, characterized by their roughness, exhibited the largest discrepancy in contact surface strength between the two sands, with a difference of 26.36 kPa. Conversely, steel piles have the smoothest surface; their grooves or protrusions are insignificant compared to the average particle sizes of both sands, leading to predominantly sliding shear deformation and the smallest strength difference of 3.58 kPa. Aluminum alloy piles, possessing a roughness intermediate to that of concrete and steel piles, exhibited an intermediate strength difference of 15.73 kPa. In conclusion, the impact of gradation on shear strength is primarily governed by roughness. Within a specific roughness range, a higher roughness corresponds to a more significant influence of gradation differences on friction strength.

Interface friction coefficient

To have a better understanding of the effect of the gradation on calcareous sand–structure interface behaviors, the interface friction coefficient were compared for each sample. Figure 7a shows the definition of the interface friction coefficient for the soil–structure interface (the peak or maximum shear stress of calcareous sand-concrete pile interface is taken as an example). For the soil–structure interface shear test, especially for cohesionless soil, fitting between the shear and normal stresses can be considered through the origin in the plot (see examples in4,40,41,42,43). Thus, this fitting method was also applied for the determinations of the interface friction coefficient in this study. Following this method, it can be observed from Fig. 8 that the variation of the shear stress τ with the normal stress σn presents a linear relationship with high accuracy (coefficient of determination R2 exceeding 0.980), determining the tangent value of the interface friction coefficient as the slope of the fitting line, and its expression is as follows:

where μ is the friction coefficient, δ is the friction angle of the soil-structure interface.

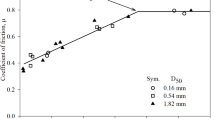

From a mathematical perspective, a linear function suggests that the interface friction coefficient remains constant, independent of normal stress. Contrary to the calcareous sand examined in this study, previous research by Uesugi and Kishida23, based on simple shear test results of quartz sand-steel interfaces, Pra-ai44, utilizing direct shear test results of sand and various structural interfaces, and Ho et al.45 and Rui et al.16, relying on ring shear test results of interfaces, consistently indicates that normal stress has a negligible impact on the interface friction coefficient. According to Eq. (3), the peak friction coefficient (μp) and residual friction coefficient (μr) can be mathematically represented as μp = τp/σn and μr = τr/σn, respectively. The relationship between the friction coefficient of the peak and residual values under different normal stresses and the percentage of 2–5 mm soil particles is drawn, as shown in Fig. 9.

As illustrated in Fig. 9, the peak and residual friction coefficients exhibit a decreasing trend with an increase in coarse particle content. Notably, a distinct turning point is observed at a coarse particle content of 15%. Specifically, when the coarse particle content is below 15%, both coefficients decrease rapidly. Conversely, when the content exceeds 15%, the rate of decrease slows down significantly, approaching a gradual decline.

Particle breakage

Based on prior scholarly research on the thickness of the interface, it is evident that the average particle size (d50) influences, to some extent, the self-locking, rotational, and adjustment capabilities among particles, as well as the susceptibility to particle crushing12,16. Feng et al.12, through direct shear tests on coral sand-structure interfaces, observed variations in the shear zone thickness during the shear process: it initiates at 3.28d50, increases to 5.47d50 during the elastic stage, decreases to 3.83d50 at the initial yield stage, and subsequently diminishes to 3.06d50 in the plastic stage. Particle crushing initiates at the initial yield stage and is predominantly concentrated within this range. Furthermore, Zhou et al.46, using ring shear tests on the interface between coral sand and steel plates, determined that the extent of particle crushing is approximately 5-6d50 and noted that the roughness of the structural panel and normal stress have negligible effects on the thickness of the shear zone. Based on the above literature, this paper assumes that the range of particle crushing is within 6d50 around the pile. The effect of gradation on particle breakage was explored by quantitatively analyzing the particle crushing rate of calcareous sand in this thickness range. Notably, within the particle crushing zone, the proximity to the structural surface correlates positively with the degree of particle crushing. The present study employs Hardin’s relative breakage index (Bᵣ) to quantitatively evaluate the particle breakage of calcareous sand. It should be noted that the reported breakage rate represents a spatially averaged value across the interfacial shear zone.

(1) Evolution of particle size distribution curve.

The particle size distribution curves for calcareous sands, both prior to and following interface shear tests involving 4C0 piles under a normal stress of 100 kPa, are depicted in Fig. 9.

As illustrated in Fig. 10, during the shearing process, notable particle fragmentation was observed on the interface between calcareous sand of varying gradations and the concrete pile. This observation is evident in the overall upward trend of the particle size distribution curve. A comparison of the particle size distribution curves among different gradations reveals that sand #1 exhibits the most significant differences in particle size content, whereas sand #4 displays minimal differences. Furthermore, the alterations in particle size pre- and post-testing are predominantly within the range of 0.5 to 2 mm.

The strain-softening behavior observed in Fig. 6 is closely related to the particle breakage and volume response of calcareous sand at the interface. The initial peak shear stress corresponds to the maximum shear dilation potential of the soil skeleton, where particle rearrangement and interlocking dominate. The subsequent softening stage is synchronous with the development of particle breakage, indicating a fundamental transition of the volume response from shear dilation to contraction. The breakage of coarse particles fills the pores, reduces the overall porosity, and forms a denser shear band.

This mechanism is quantitatively explained by the relative breakage rate Br. As shown in Fig. 10, Sand #1 with a high content of coarse particles experiences the most significant breakage. Its severe particle breakage rapidly destroys the initial dilatant skeleton, resulting in a sharp post—peak strength decay (higher softening coefficient βs). In contrast, Sand #4, which has finer particles and stronger anti—breakage ability, can maintain a more stable particle structure10. Therefore, its softening response is slower, with less volume shrinkage, and the interface shear is maintained by a more durable particle framework.

(2) Evolution of gradation characteristic parameters.

To analyze the variations in particle breakage and state evolution laws of sands with varying gradations, Table 5 presents the changes of single characteristic particle size (d10, d30, d50, d60), the coefficient of uniformity (Cu), and the coefficient of curvature (Cc).

As Table 5 indicates, for various gradations, each individual characteristic particle size (d10, d30, d50, d60) exhibited a decreasing trend both before and after interface shear. However, the changes in the coefficient of uniformity (Cu) and the curvature coefficient (Cc) were inconsistent. Using d50 as a representative of the individual characteristic particle size index, the relationships among d50, Cu, Cc, and the content of coarse particles are illustrated in Fig. 10.

From Fig. 11, it is evident that for various gradations, d50 exhibits a decreasing trend following shearing, suggesting that particle breakage results in an overall reduction in the particle size. As the fine particle content increases, this decreasing trend gradually diminishes, indicating a decrease in the degree of particle breakage. The variations in Cu and Cc among different gradations are inconsistent. Specifically, Cu increases after shearing for all graded sands except sand 3#, and Cc increases for all graded sands except sand 2#. Consequently, among the aforementioned gradation characteristic parameters, individual particle sizes (d10, d30, d50, d60) provide a more accurate description of the differences in particle breakage among various gradations.

Improvement of gradation equation

Based on the aforementioned research, it is evident that scholars primarily employ single characteristic particle sizes (d10, d30, d50, d60) or the coefficient of uniformity (Cu) to delineate differences in gradation when analyzing the influence of gradation on interfacial shear behavior. However, sands with identical Cu and Cc values can exhibit differing gradations24. Similarly, even with an identical single characteristic particle size, the gradation curve may still vary28. Therefore, neither Cu and Cc nor a single characteristic particle size can serve as a unique descriptor of the gradation curve, and it is more challenging to uniformly describe the impact of individual particle sizes and various gradations on interfacial friction strength, thereby limiting the generalizability of the aforementioned research conclusions to other engineering scenarios. Scholars have endeavored to address this issue by developing grading equations, as demonstrated by Talbot and Richart30, Zhu et al.32, Zhu et al.33, and Wu et al.25,26.

Applicability verification of existing gradation equation

Currently, the commonly used grading equations are the fractal grading equation proposed by Talbot and Richart30, the two-parameter grading equation proposed by Zhu et al.32 and Zhu et al. 33, and the single-parameter grading equation proposed by Wu et al.25,26. The precise formulations of these equations are depicted in Eqs. (4) to (7), respectively.

where P represents the percentage of particles with a size less than d, d denotes the particle size, dmax is the maximum particle size, and D represents the fractal dimension. When b = 0 and m = 3-D, Eq. (5) coincides with Eq. (4). In this context, x denotes d/dmax, c and n are model parameters, Additionally, β is the gradation parameter with a value range of (0 < β < 1). When \(m={{\sqrt b }}\), Eq. (7) is identical to Eq. (5). Figure 11 illustrates the fitting results of the four grading equations mentioned above to the grading curves of four types of calcareous sand, while Table 6 lists the fitting parameters for these four grading equations.

By examining Table 6 and Fig. 12, we observe that, with the exception of the Talbot fractal equation, the remaining three grading equations are capable of describing the grading characteristics of Sands 2#, 3#, and 4# to some extent. Among these equations, the order of their descriptive accuracy is as follows: the two-parameter grading equation proposed by Zhu et al.32, the two-parameter grading equation proposed by Zhu et al.33, and the single-parameter grading equation proposed by25,26. However, none of these four grading equations can effectively fit Sand 1#. The primary reason for this is that these grading equations are primarily designed to describe continuous grading curves with a wide range, and they are not applicable to single-size fractions. Specifically, in this study, Sand 1# consists entirely (100%) of particles in the 2–5 mm size range, categorizing it as a single-size fraction, and thus, all four grading equations are unsuitable.

Improvement of gradation equation

To uniformly describe both uniform grading curves and continuous grading curves, this paper enhances the two-parameter gradation equation proposed by Zhu et al.32. It introduces a gradation equation capable of simultaneously depicting both uniform grading curves and continuous grading curves, and examines the variation patterns of gradation parameters across different single particle size groups.

After transforming the two-parameter gradation Eq. (5) proposed by Zhu et al.32, we obtained:

When fitting a uniform grading curve (such as 20 ~10, 5 ~2, 0.25 ~0.075, etc.) using Eq. (8), we found that the parameters b and m exhibited abnormalities and were not uniquely determined. This is primarily attributable to the fact that Eq. (4) solely specifies the maximum particle size (dmax), which implicitly assumes a default particle size range of 0 to dmax. Consequently, it cannot accurately describe a uniform grading curve with a non-zero minimum particle size. In response to this shortcoming, we have modified Eq. (8), and the improved form is as follows:

where c0 denotes a small constant, set to 0.001, and dmin represents the minimum particle size. Equation (9) specifies dmin in the denominator of Eq. (8), ensuring that the particle size description interval is confined to dmin ~dmax, thereby uniquely determining the parameters m and b. When dmin = 0, Eq. (9) reduces to Eq. (8).

When Eq. (9) is utilized to describe continuous grading curves, Zhu et al.32 have conducted a detailed discussion on the range of values for the grading parameters m and b. This study solely examines the values of grading parameters for uniform grading curves. Regardless of whether the grading curve represents continuous grading or a uniform grading curve, P is an increasing function of d. Therefore, according to Eq. (9), we can conclude that the partial derivative of P with respect to d should be greater than 0.

Equation (10) holds only if m (1-b) > 0. There are two combinations of the values of parameters m and b: ①m > 0 and b < 1; ②m < 0 and b > 1. In addition, when the grading curve represents a single particle size, the value of d has only two possibilities: d = dmax or d = dmin.

For Eq. (11) to be valid, b = 0 is necessary. Substituting b = 0 into Eq. (12), the requirement for Eq. (12) to hold true necessitates that m adopt a larger positive value. By comparing the parameter ranges for m and b in Eq. (10), it becomes evident that when b = 0 and m assumes a large positive value, Eq. (9) satisfies the monotonic increase of the single particle size grading equation, along with the value characteristics of the maximum and minimum values. Equation (9) was utilized to fit uniform grading curve, and the resulting grading parameters are presented in Table 7.

From Table 7, it is evident that for distinct single-size fractions, when dmin/dmax is identical, they exhibit the same grading parameters m and b. However, for a given dmax, the grading curve can be uniquely determined solely by Eq. (9). Consequently, Eq. (9) can serve as a unified grading equation for describing both uniform and continuous grading curves.

Gradation index

Equation (9) can uniformly represent both uniform grading curves and continuous grading curves, but it contains two gradation parameters, m and b. To quantitatively analyze the impact of gradation on the mechanical properties of soil or interfaces, it is essential to establish distinct relationships between the gradation parameters m and b and mechanical property indicators. However, this increases the complexity of the description and hinders practical application. Consequently, it is necessary to explore more reasonable gradation indicators to more conveniently and quantitatively describe the influence of gradation. Zhu et al.32 proposed the concept of gradation area S to represent the influence of gradation. This area refers to the region enclosed by the maximum particle size line, the gradation curve, the abscissa axis, and d = dk in the P-lgd plane, as shown in Fig. 13a.

Definition of gradation area index. (a) Gradation area S32, (b) Gradation area Sm (in this paper).

Based on the concept of grading area S proposed by Zhu et al.32, the calculation equation of S can be derived according to the improved grading Eq. (9)

where

where, t = exp(c0*dmin/dmax), dk represents the corresponding particle size when P = k. The Eq. (14) represents the area enclosed by the gradation curve and the coordinate axes as the parameter k approaches 0. When k tends towards 0, theoretically, the corresponding particle size d would be 0 mm. However, in practice, the minimum particle size of soil particles cannot be 0 mm. Therefore, we assign k a minute nonzero value, which aligns more closely with the actual gradation distribution. Specifically, when b = 0, using Eq. (13) and the limit conception, we can obtain

From Eq. (15), it can be observed that the calculated result of S only depends on k and m. Among them, k is usually taken as a constant, while the parameter m corresponding to different single particle sizes may be the same (as shown in Table 8). This can lead to the possibility that the area S enclosed by different gradation curves and the coordinate axes may be the same. Therefore, the area S enclosed by the gradation curve and the maximum particle size line, as defined by Zhu et al.32, cannot reflect the influence of single particle size gradation.

In the process of developing the relative breakage rate indicator Br, Hardin47 employed a methodology that utilizes the area enclosed by a particle size of d = 0.074 mm and the initial grading curve as a measure of breakage potential, providing significant insight for this study. Although in the P-lgd coordinate system, individual particle size curves may exhibit the same slope due to identical dmin/dmax ratios, the areas enclosed by different particle sizes and the d = 0 mm line, as well as the P = 100% line, necessarily vary. Consequently, this area can be utilized to represent differences in grading and is denoted as Sm, as illustrated in Fig. 13(b). However, given that soil particle sizes in nature cannot reach a minimum of 0 mm, this study utilizes d = 0.001 mm as the minimum value for calculations. This paper intends to derive the area Sm of the gradation curve in the P-lgd plane through the gradation equation (Eq. (9)), that is, the area enclosed by the d = 0.001 mm line, the gradation curve and the P = 100% line, which can be expressed as

It can be obtained from Eq. (5),

Since the minimum value of P can only approach zero asymptotically but cannot attain zero exactly, it is impractical to directly integrate P within the range of 0 to 1 when calculating the area using integration. In this study, the area Sm enclosed by the gradation curve, the d = 0.001 mm line, and the P = 100% line is partitioned into two segments, S1 and S2, as illustrated in Fig. 13b. Specifically, S1 is enclosed by the gradation curve, the d = 0.001 mm line, the P = 100% line, and the P = k1 line. Here, P can be integrated, where k1 is a minute value typically set to 0.001. S2 is a rectangle with a length of lgdk1-lg0.001 and a height of k1, and its area can be computed directly. As k1 approaches zero, the sum of S1 and S2 approximates the total area Sm.

Combining Eqs. (16) and (17), we can get

In particular, when b = 0, we can obtain

We have derived the grading curve area, Sm, based on the modified two-parameter grading equation (Eq. (9)). Compared to Eqs. (13), (20) introduces an additional control parameter, dmax, which enables differentiation between individual particle size gradings. Consequently, using the grading curve area, Sm, derived from the modified two-parameter grading equation (Eq. (9)), we can quantitatively describe the impact of both individual particle sizes and continuous grading curves.

The grading area Sm for various uniform grading curves was computed using Eq. (20). The results obtained through the trapezoidal segmentation method were utilized for comparison, as presented in Table 8. Analysis of Table 8 reveals slight discrepancies between the Sm values calculated using the Eq. (20) and the trapezoidal segmentation method. This discrepancy arises because, when calculating the grading area according to Eq. (20), the minimum value of P can only asymptotically approach 0, resulting in a deviation from the area computed by the trapezoidal method. However, the magnitude of this deviation is relatively minor. Additionally, the grading area calculated using the Eq. (20) accurately captures the differences among various uniform grading curves, thereby preserving its utility in subsequent research endeavors.

The relationship between friction coefficient, particle breakage and gradation index

To quantitatively analyze the influence of gradation on the shear strength of the interface and particle breakage, the gradation area Sm defined previously was employed to examine the relationship between peak friction coefficient, residual friction coefficient, particle breakage rate, and gradation index. Using the improved grading equation (Eq. (9)), the four grading curves presented in this paper were fitted, and the area Sm enclosed by each grading curve with the line d = 0.001 mm and the line P = 100% was calculated through Eq. (20). The fitting results are shown in Table 8.

(1) Evolution of peak friction coefficient and residual friction coefficient.

Figure 13 illustrates the relationship between the peak friction coefficient and residual friction coefficient as they vary with the grading area Sm.

Figure 14 demonstrates that the peak friction coefficient decreases gradually with an increase in the grading area Sm, eventually leveling off. The residual friction coefficient follows a similar trend, albeit with a slower rate of decrease compared to the peak friction coefficient (Fig. 14 and 15). The relationships among the peak friction coefficient, residual friction coefficient, and grading area Sm can be modeled using an exponential function, as follows:

where a2, b2 and c2 are the fitting parameters. For the four gradations discussed in this paper, the peak friction coefficient fitting parameters are a2 = 0.56, b2 = 1.8 × 106, c2 = -15.74, with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.98. The fitting parameters of residual friction coefficient are a2 = 0.27, b2 = 6.7 × 108, c2 = -22.06, with a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.97.

(2) Evolution of relative breakage rate Br.

Under a normal stress of 100 kPa, Fig. 14 illustrates the variation curve of the particle breakage rate Br (proposed by47) at the interface for different gradations, plotted as a function of the gradation area Sm.

Figure 16 demonstrates that the relationship between particle breakage rate Br and grading area Sm can be approximately represented by a linear function, which can be expressed as

where ks1 and ks2 are the fitting parameters. When the normal stress remains constant, the initial gradation has a significant impact on the variation of particle size in the interface. Specifically, the coarser the particles in the sample, the more severe the particle breakage phenomenon on the interface. However, as the content of fine particles increases, the degree of particle breakage gradually decreases.

Conclusion

This study investigates the influence of particle gradation on the shear behavior and particle breakage at the interface between calcareous sand and structural materials (concrete, aluminum alloy, and steel piles). A self-developed large-scale interface shear apparatus was employed to analyze four distinct gradations of calcareous sand. An improved two-parameter gradation equation, building upon the model by Zhu et al.32, was formulated, and a novel gradation index (Sm) was introduced to quantify gradation effects. Functional relationships between Sm, interface friction coefficients, and particle breakage rates were established. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Shear Stress Response: Under the tested normal stress range, increasing coarse particle content (from sand 4# to 1#) reduced both peak and residual shear stresses, with gradation effects amplifying at higher normal stresses. Softer shear responses (softening coefficient βs = 47.66–54.98%) correlated with finer gradations. Surface roughness dominated shear strength, with concrete > aluminum alloy > steel piles.

-

(2)

Friction coefficients and Breakage: For a given structural surface, friction coefficients (peak/residual) declined with coarse particle content, governed by particle-structure interlocking modulated by relative particle size and surface roughness. A power-law function best described shear strength, while particle breakage intensified with coarser gradations (sand #1 exhibited maximal breakage vs. minimal in #4).

-

(3)

Gradation Quantification: The proposed enhanced gradation equation unified descriptions of both uniform and continuous gradations. The derived gradation area (Sm) correlated exponentially with friction coefficients and linearly with breakage rates, offering a robust metric for gradation impact.

This study provides novel insights into the shear behavior of calcareous sand-structure interfaces through the development of an improved gradation equation and the introduction of a quantitative gradation index (Sm). The proposed framework successfully correlates particle size distribution with interfacial shear strength and particle breakage, offering a universal approach applicable to other granular materials and engineering scenarios, such as offshore foundations, slope stability, and even extraterrestrial soil-structure interactions. The exponential relationship between Sm and friction coefficients, along with the linear correlation with particle breakage rates, establishes a predictive model for optimizing geotechnical designs in particle-sensitive environments. However, the empirical models (Eqs. 22 and 23) proposed in this study are derived from a specific dataset, and their general accuracy and broader applicability indeed require further validation with a more extensive range of experimental conditions in future work.

Looking ahead, future research should explore the effects of cyclic and dynamic loading on gradation evolution, integrate Sm with discrete element modeling (DEM) to simulate particle-scale mechanisms, and validate the framework across a broader range of materials, including biocemented or fiber-reinforced soils. These advancements will further bridge the gap between granular mechanics and practical engineering, enabling more resilient infrastructure in challenging geotechnical conditions. The findings not only enhance the fundamental understanding of granular-structure interactions but also provide actionable tools for engineering applications in marine, terrestrial, and planetary environments.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Lehane, B.M., Schneider, J.A., & Xu, X. The UWA-05 method for prediction of axial capacity of driven piles in sand. In Proc., 1st Int. Symp. on Frontiers in Offshore Geotechnics. Perth, Australia: Balkema, 683–689 (2005).

Park, S., Hossain, M. S., Kim, Y., Ullah, S. N. & Hu, Y. Installation and inclined loading of a suction caisson anchor in calcareous sand. Ocean Eng. 316, 119997 (2005).

Pei, H., Wang, D. & Liu, Q. Numerical study of relationships between the cone resistances and footing bearing capacities in silica and calcareous sands. Comput. Geotech. 155, 105220 (2023).

Wang, T., Song, Y., Wang, L. & Han, Q. Experimental investigation of uncertain factors on the mechanical properties of half-grouted sleeve connected with large-diameter high-strength reinforcement. J. Build. Eng. 88, 109087 (2024).

Wang, X., Wen, D., Ding, H. & Liu, K. Improving erosion resistance of calcareous sand slope with zinc sulfate solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 447, 138113 (2024).

Xiao, Y., Cui, H., Shi, J., Qiao, W. & Stuedlein, A. W. Shear response of calcareous sand-steel snake skin-inspired interfaces. Acta Geotech. 19(3), 1517–1527 (2024).

Yu, K., Ran, Y., Shi, J., Duan, M. & Ouyang, Z. Physical property of MICP-treated calcareous sand under seawater conditions by CPTU. Biogeotechnics 3(1), 100131 (2025).

Feng, W. Q., Bayat, M., Mousavi, Z., Li, A. G. & Lin, J. F. Shear strength enhancement at the sand-steel interface: A pioneering approach with Polyurethane Foam Adhesive (PFA). Constr. Build. Mater. 429, 136297 (2024).

Feng, W. Q., Zhang, T. Y., Li, Y. X. & Xu, D. S. Experimental study of interface performance between calcareous sand and steel pile with different surface roughness and temperatures. Ocean Eng. 292, 116469 (2024).

Peng, Y., Yin, Z. Y., Yang, F., Qu, L. & Ding, X. Analysis of the effect of breakable particle corners on uplift pile–soil interaction behaviors in calcareous sand. Acta Geotech. 19(11), 7307–7328 (2024).

Yasufuku, N., & Ochiai, H. Sand-steel interface friction related to soil crushability. In Geomechanics: Testing Modeling and Simulation 627–641 (2005).

Feng, Z., Xu, W. & Meng, Q. Mechanical behaviors of interaction between coral sand and structure surface. J. Central South Univ. 27(11), 3436–3449 (2020).

Han, F., Ganju, E., Salgado, R. & Prezzi, M. Effects of interface roughness particle geometry and gradation on the sand–steel interface friction angle. J. Geotechn. Geoenviron. Eng. 144(12), 04018096 (2018).

Hejazi, M., Fakharian, K. & Kaviani-Hamedani, F. Permanent deformation and particle crushability of calcareous sands under cyclic traffic-induced loadings through simple shear apparatus. Transp. Geotechn. 49, 101428 (2024).

Öztürk, M. Effect of aperture size on the interface shear behavior of gridded cementitious geocomposite on sand soil with different relative densities. Constr. Build. Mater. 432, 136653 (2024).

Rui, S., Wang, L., Guo, Z., Cheng, X. & Wu, B. Monotonic behavior of interface shear between carbonate sands and steel. Acta Geotech. 16, 167–187 (2021).

Wang, H. L., Zhang, Q. Y., Yin, Z. Y. & Jing, H. Effect of sand particle size on interface shear behaviour between bio-cemented sand by MICP treatment and steel structure. Can. Geotech. J. 60(3), 269–286 (2022).

Gao, J., Zhan, X., Liu, F., Zhou, X. & Ji, C. Study on dynamic shear properties of rubber modified calcareous sand with different shapes and contents. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 190, 109184 (2025).

Gao, Y., Shi, X., Yuan, Q., Sun, L. & Sun, K. Particle breakage and uneven settlement characteristics of calcareous sand foundation. J. Build. Eng. 100, 111662 (2025).

Xu, D. S., Shen, G., Liu, Q. M. & Du, W. B. Dynamic mechanical response and particle breakage characteristics of calcareous sand. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 181, 108653 (2024).

Chen, Y. Y. et al. Study on the mechanical properties of coral sands with different particle gradations. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 41(3), 327–338 (2022).

Sha, F., Zhang, L., Zhang, M., Zuo, Y. & Niu, H. Penetration grouting diffusion and strengthening mechanism of sand layer with crucial grout. J. Build. Eng. 91, 109585 (2024).

Uesugi, M. & Kishida, H. Influential factors of friction between steel and dry sands. Soils Found. 26(2), 33–46 (1986).

Wang, H. L., Zhou, W. H., Yin, Z. Y. & Jie, X. X. Effect of grain size distribution of sandy soil on shearing behaviors at soil–structure interface. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 31(10), 04019238 (2019).

Wu, E., Zhu, J., Guo, W. & Zhang, Z. Effect of gradation on the compactability of coarse-grained soils. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 24(2), 356–364 (2020).

Wu, E. L., Zhu, J. G., Wang, L. & Chen, G. Single-parameter gradation equation for coarse-grained soil and its applicability. Rock Soil Mech. 41(3), 831–836 (2020).

Xie, K. et al. A framework for determining the optimal moisture content of high-speed railway-graded aggregate materials based on the lab vibration compaction method. Constr. Build. Mater. 392, 131764 (2023).

Kim, D. & Ha, S. Effects of particle size on the shear behavior of coarse grained soils reinforced with geogrid. Materials 7(2), 963–979 (2014).

Liang, Y., Yeh, T. C. J., Wang, J., Liu, M. & Hao, Y. Effect of particle size distribution on soil-steel interface shear behavior. Soil Mech. Found. Eng. 54(5), 310–317 (2017).

Talbot, A. N. & Richart, F. E. The strength of concrete-its relation to the cement aggregates and water. Illinois Univ. Eng. Exp. Sta Bull. 137(1), 1–118 (1923).

Swamee, P. K. & Ojha, C. S. P. Bed-load and suspended-load transport of nonuniform sediments. J. Hydraul. Eng. 117(6), 774–787 (1991).

Zhu, J. G., Guo, W. L., Wen, Y. F., Yin, J. H. & Zhou, C. New gradation equation and applicability for particle-size distributions of various soils. Int. J. Geomech. 18(2), 04017155 (2018).

Zhu, S. Gradation equation and compaction characteristics of continuously distributed coarse-grained soil. Chin J. Geotechn. Eng. 4110, 1899–1906 (2019).

Zhang, X., Baudet, B. A., Hu, W. & Xu, Q. Characterisation of the ultimate particle size distribution of uniform and gap-graded soils. Soils Found. 57(4), 603–618 (2017).

Dong, Z. L., Tong, C. X., Zhang, S., Teng, J. D. & Sheng, D. A comparative study on shear Behavior of uniform-, gap-, and fractal-graded carbonate soils. J. Geotechn. Geoenviron. Eng. 150(1), 04023128 (2024).

Liu, Q. B. & Lehane, B. M. The influence of particle shape on the (centrifuge) cone penetration test (CPT) end resistance in uniformly graded granular soils. Géotechnique 62(11), 973–984 (2012).

Zhao, X., Xiao, Z. & Wang, Q. Relationship between surface hardness and peak interfacial frictional coefficient in a laboratory scale setting. Appl. Sci. 12(20), 10607 (2022).

Liu, R.M., Li, L.B., Maimaiti, N., & Chen, P. Research on sample preparation of calcareous and silica sand with air pluviation method. In Marine Georesources & Geotechnology, 1–15 (2025).

Subba Rao, K. S., Rao, K. S. S., Allam, M. M. & Robinson, R. G. Interfacial friction between sands and solid surfaces. Proc. Inst. Civil Eng. Geotechn. Eng. 131(2), 75–82 (1998).

Eid, H. T., Amarasinghe, R. S., Rabie, K. H. & Wijewickreme, D. Residual shear strength of fine-grained soils and soil–solid interfaces at low effective normal stresses. Can. Geotech. J. 52(2), 198–210 (2015).

Hu, L. & Pu, J. Testing and modeling of soil-structure interface. J. Geotechn. Geoenviron. Eng. 130(8), 851–860 (2004).

Sánchez-Mendieta, C., Galán-Díaz, J. J. & Martinez-Lage, I. Relationships between density porosity compressive strength and permeability in porous concretes: optimization of properties through control of the water-cement ratio and aggregate type. J. Building Engineering 97, 110858 (2024).

Wang, J. J., Zhang, H. P., Tang, S. C. & Liang, Y. Effects of particle size distribution on shear strength of accumulation soil. J. Geotechn. Geoenviron. Eng. 139(11), 1994–1997 (2013).

Pra-ai, S. Behaviour of soil-structure interfaces subjected to a large number of cycles Application to Piles (Universite de Grenoble, 2013).

Ho, T. Y. K., Jardine, R. J. & Anh-Minh, N. Large-displacement interface shear between steel and granular media. Géotechnique 61(3), 221–234 (2011).

Zhou, W. H., Jing, X. Y., Yin, Z. Y. & Geng, X. Effects of particle sphericity and initial fabric on the shearing behavior of soil–rough structural interface. Acta Geotech. 14, 1699–1716 (2019).

Hardin, B. O. Crushing of soil particles. J. Geotechn. Eng. 111(10), 1177–1192 (1985).

Funding

This research was funded by the Introduction of Talent Research Initiation Fund of Kashi University (No. GCC2024ZK-018), the Institutional Research Grant (No. (2024)2877), and the College Students’ Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (No. 202510763147, 202510763224). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the fundings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruiming Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing-Original draft preparation, Writing-Review & Editing; Wenbang Zhu: Data curation, Writing-Original draft preparation, Investigation; Yabo Shi: Visualization, Validation; Yali Cao: Software, Visualization; Longlong Wei: Supervision, Data curation; Chaochao Sun: Visualization, Formal analysis; Xiumei Zheng: Supervision, Data curation, Writing-Review & Editing;

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, R., Zhu, W., Shi, Y. et al. Unified gradation index (Sm) for shear mechanics and particle breakage at calcareous sand-structure interfaces. Sci Rep 16, 1131 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30892-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30892-8