Abstract

Traditional evaluations of surgical skill rely heavily on subjective assessments, limiting precision and scalability in modern surgical education. With the emergence of robotic platforms and simulation-based training, there is a pressing need for objective, interpretable, and scalable tools to assess technical proficiency in surgery. This study introduces an explainable machine learning (XAI) framework using surface electromyography (sEMG) and accelerometer data to classify surgeon skill levels and uncover actionable neuromuscular biomarkers of expertise. Twenty-six participants, including novices, residents, and expert urologists, performed standardized robotic tasks (suturing, knot tying, and peg transfers) while sEMG and motion data were recorded from 12 upper-extremity muscle sites using Delsys® Trigno™ wireless sensors. Time- and frequency-domain features, along with nonlinear dynamical measures such as Lyapunov exponents, entropy, and fractal dimensions, were extracted and fed into multiple supervised machine learning classifiers (SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost, Naïve Bayes). Classification performance was evaluated using accuracy, F1-score, MCC, and AUC. To ensure interpretability, SHAP and LIME were employed to identify and visualize key features distinguishing skill levels. Ensemble models (XGBoost and Random Forest) outperformed others, achieving classification accuracies above 72%, with high F1-scores for all classes. Nonlinear features, particularly Mean_Long_Lyapunov exponent, Correlation Dimension, Approximate Entropy, and Hurst exponent, consistently ranked among the top predictors. Expert surgeons exhibited higher movement complexity and temporal consistency, reflected in higher entropy and correlation dimension, and lower Lyapunov exponents compared to novices. XAI methods revealed that different classes were driven by distinct feature sets: entropy measures best identified novice patterns, while fractal and stability features were more predictive of expert performance. SHAP and LIME enabled both global and instance-specific interpretation of classifier decisions, enhancing transparency and enabling targeted feedback. This study demonstrates the feasibility and utility of combining multimodal wearable sensor data with explainable machine learning to assess robotic surgical skill. The identified biomarkers capture nuanced aspects of motor control such as adaptability, complexity, and stability that distinguish novice, intermediate, and expert surgeons. Beyond classification, the explainable framework offers interpretable insights into why specific skill levels were assigned, providing a pathway for personalized surgical feedback and training. This approach advances the development of objective, transparent, and clinically meaningful assessment tools in surgical education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Technical proficiency in surgery is a critical determinant of patient outcomes and surgical quality. Prior studies have shown that surgeons with superior technical skills achieve significantly lower complication rates than their less skilled counterparts (e.g., 5.2% vs. 14.5% complication rate for top- vs. bottom-quartile surgeons)1,2. In the context of robotic urologic surgery, tasks such as suturing and knot tying are fundamental, and mastery of these skills is essential for operative efficiency and patient safety. Traditionally, surgical skill has been evaluated using expert observation and global rating scales, which, while useful, are subjective and resource-intensive. As robotic surgery and simulation-based curricula expand, the need for objective, scalable, and interpretable methods of skill assessment has become increasingly urgent. Traditional approaches rely on expert observation and global rating scales, which, while informative, are inherently subjective and resource-intensive.

Recent advances in sensor technology and machine learning have enabled more quantitative evaluation of surgical performance. Wearable sensors and motion tracking systems can capture rich data on a surgeon’s technique during standardized tasks3. For example, our prior work has demonstrated that performance in simulated suturing, peg transfer, or knot-tying tasks can be assessed using surface electromyography (sEMG) to monitor muscle activation alongside kinematic measurements of instrument motion3,4. Machine learning (ML) algorithms applied to such multimodal datasets have shown promise in distinguishing novices from experts, sometimes achieving high classification accuracies5. However, a recent systematic review noted that while the majority of ML-based surgical skill assessments utilize kinematic or motion data, only a small fraction (~ 1%) of studies have incorporated physiological signals like sEMG5.

Beyond motion tracking, several groups have demonstrated that wearable force and muscle-activity signals can support accurate, scalable assessment of technical skill. For example, Xu et al. used a sensorized glove to capture fingertip forces during microsurgical tasks and trained deep models to classify surgeon expertise, achieving high accuracy and demonstrating the value of force signatures for skill assessment6. Similarly, Nguyen et al. leveraged deep neural networks on motion signals to separate novice from expert performances7. However, these models are often black boxes, offering limited transparency into why a performance is rated as novice, intermediate, or expert - a barrier to adoption in surgical education8. At the same time, studies using wearable biosensors are emerging, Soto Rodriguez et al. combined sEMG and accelerometry during a laparoscopic pattern-cutting task and showed that multimodal muscle-kinematic features reflect experience level9. Together, these studies indicate that physiologic and force cues carry complementary information to kinematics for objective skill evaluation.

Building on this line of work, we focus on explainable learning from physiological (sEMG) and inertial (accelerometry) signals during robotic suturing and peg-transfer. Unlike prior deep models optimized primarily for accuracy on force or motion data, our aim is to (i) quantify skill across three strata (novice/intermediate/expert), (ii) identify interpretable neuromuscular biomarkers (e.g., entropy, Lyapunov stability, fractal measures) linked to motor-control constructs, and (iii) provide instance-level explanations via SHAP/LIME that can be translated into targeted feedback. This complements force-glove and video/kinematics approaches by opening a window onto the muscular control strategies that underlie expert performance6,7,9.

Integrating muscle activation patterns provides a new dimension for skill assessment – offering insight into the motor control strategies and effort levels that may differ between novice and expert surgeons – and thus represents an underexplored avenue for improving assessment fidelity. Recent studies have also leveraged various biosensing modalities for fine-grained manipulation skill assessment. For instance, Li et al. utilized nonlinear spectral sEMG features to simultaneously recognize hand/wrist motion and estimate grasp force in transradial amputees, demonstrating high resolution in motor intent detection10. Similarly, Bimbraw et al. presented an ultrasound-based approach for simultaneously estimating manipulation skill and grasp force, underscoring the growing relevance of multimodal biosensing including ultrasound, EMG, and kinematics in objective skill estimation11. These studies illustrate the broader landscape of human-machine interface (HMI) research focused on precise motor decoding, which complements our wearable sensor-based skill classification framework.

A key challenge in deploying ML for surgical education and assessment is the interpretability of model outputs. Conventional assessments (or even black-box ML models) that yield a single score or rating often fail to provide specific feedback on how a trainee can improve12. In response, there is growing emphasis on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques to ensure that automated skill assessment tools are transparent and clinically interpretable8. Interpretability is critical for gaining clinician trust and translating algorithmic evaluations into actionable feedback. Notably, recent work has demonstrated the value of XAI in this domain. For instance, one study on a surgical procedure achieved high accuracy (89–94%) in classifying surgeon skill and used SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to identify the key motion and force features distinguishing experienced surgeons from novices12. This explainable model provided visual, real-time feedback to surgeons with suboptimal technique, highlighting specific aspects of their performance in need of improvement12. The authors concluded that such explainable ML methods can substantially enhance objective skill assessment and guide targeted training interventions12. More broadly, the surgical community recognizes that transparency and interpretability are essential for the effective integration of AI models into clinical practice8.

In this study, we present a rigorous approach to objectively assess surgical skill in robotic urology tasks, with a focus on clinical relevance, methodological rigor, and model interpretability. We recruited attending surgeons, fellows, and residents and stratified them into novice, intermediate, and expert groups based on their years of robotic surgical experience. All participants performed standardized robotic suturing and knot-tying tasks, which are key components of urologic surgical training and simulation curricula. During these tasks, we collected high-resolution performance data using sEMG sensors (capturing muscle activation from key upper-extremity muscle groups) and accelerometry. We then trained machine learning models to analyze this multimodal dataset and automatically distinguish skill levels. Crucially, we applied XAI techniques (such as feature importance analysis and model-agnostic interpretability methods) to the trained models to identify the most salient muscle and digital biomarkers of surgical expertise. By elucidating which specific muscle and related digital biomarker metrics contribute to proficient vs. suboptimal performance, our approach yields interpretable insights that go beyond a raw skill score. These insights underscore the why behind an individual’s performance, providing concrete targets for improvement. The ability to pinpoint key biomechanical factors allows for actionable feedback – for example, advising a trainee to adjust grip technique or reduce extraneous movements – and can inform personalized training regimens. Furthermore, by highlighting objective digital biomarkers of skill, this approach could be extended to monitor skill development over time or to guide rehabilitation strategies for surgeons recovering from injury or retraining after a period of inactivity. In summary, our work demonstrates that combining multimodal sensor data with explainable ML can enhance the objectivity, interpretability, and practical utility of surgical skill assessment in robotic surgery, ultimately supporting better training outcomes and patient care.

Methods

Participants

A total of 26 individuals from the Department of Urology at the University of California, Irvine, were recruited for this study. Participants were stratified into three groups based on surgical experience and proficiency: Novice group (n = 10): Undergraduate or medical students with no prior surgical training or clinical experience; Intermediate group (n = 11): Urology residents in postgraduate years (PGY) 1 through 5; Expert group (n = 5): Practicing urologists with over five years of independent surgical experience. Intermediate group (n = 11): Urology residents in postgraduate years (PGY) 1 through 5. We acknowledge this represents a wide range of experience levels. PGY-1 residents were relatively novice in robotic tasks, whereas PGY-5 residents had greater surgical exposure, though not yet at the level of independent attending surgeons. Participants were stratified by surgical training level; however, we did not formally screen for prior musculoskeletal injuries or recent surgeries within the past 6–12 months. No participants reported acute conditions at the time of recruitment, but the absence of structured musculoskeletal screening is noted as a limitation of the present study.

Participant recruitment adhered to institutional ethical guidelines, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. This study was approved by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board (UCI-IRB) and all methods were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental setup

Participants were instructed to complete three standardized robotic surgical tasks commonly used in simulation-based training curricula: pegboard transfer, knot tying, and robotic suturing. Each participant performed a minimum of three trials per task to ensure data reliability and reduce trial-to-trial variability. To prevent over-representation from participants who completed more trials, we capped the number of included trials at three per participant per task (selecting the first three valid trials), so each participant contributed a comparable amount of data.

During each trial, muscle activation and movement kinematics were recorded using sEMG integrated with triaxial accelerometers. sEMG signals were sampled at 2,000 Hz and accelerometer signals at 148 Hz using the Delsys® Trigno™ Wireless system (Delsys Inc., Boston, MA). These acquisition rates ensured adequate capture of the spectral characteristics of muscle activity and movement dynamics during surgical tasks. Data acquisition was performed using the DELSYS® Trigno™ Wireless system (Delsys Inc., Boston, MA), with 12 sEMG electrodes placed bilaterally over key upper-extremity muscles involved in fine motor control and stabilization during surgical tasks: Biceps brachii, Triceps brachii, Anterior deltoid, Flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), Extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU), Thenar eminence (TE). sEMG electrodes were placed according to SENIAM guidelines13 (for biceps brachii, triceps brachii, anterior deltoid) and standard clinical practice for other muscles (FCU, ECU, thenar eminence). Prior to electrode placement, the skin was shaved if needed, abraded, and cleaned with 70% isopropyl alcohol to minimize impedance. Electrode placement was conducted with the assistance of a licensed physical therapist specializing in upper-extremity anatomy to ensure consistent and accurate positioning. All EMG signals were normalized to each participant’s maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) to control for inter-individual variability in muscle strength and activation amplitude. For MVC’s standardized positions were used: Biceps brachii- Elbow flexion against manual resistance at 90° flexion; Triceps brachii- Elbow extension against manual resistance at 90° flexion; Anterior deltoid- Shoulder flexion against manual resistance at 90° flexion; Flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU)- Wrist flexion with ulnar deviation against resistance; Extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU)- Wrist extension with ulnar deviation against resistance; Thenar eminence (TE)- Thumb abduction against manual resistance. Although our experimental setup was visually similar to that reported previously3, the present study included a different cohort of participants who underwent the same standardized robotic tasks. The datasets are therefore distinct, though collected under comparable protocols. This study reanalyzes the dataset previously reported in3, extending it by incorporating explainable AI methods (SHAP/LIME) and nonlinear dynamical biomarkers to provide interpretable skill assessments.

Data preprocessing

Raw sEMG and accelerometer signals were subjected to a standardized preprocessing pipeline. For sEMG, signals were band-pass filtered between 20 and 450 Hz using a 4th-order zero-lag Butterworth filter to remove motion artifacts and high-frequency noise. A 60 Hz notch filter was applied to suppress powerline interference. Accelerometer data were band-pass filtered between 0.25 and 20 Hz to capture movement-related frequencies while minimizing sensor drift and high-frequency artifacts. Artifact removal was conducted by first identifying signal segments where amplitudes exceeded ± 3 standard deviations of the mean (indicative of motion or electrode disturbance). These segments were flagged and excluded from feature extraction. Channels with more than 10% contaminated samples in a trial were discarded for that trial.

For missing values (due to transient sensor dropouts or removal of artifacts), we applied linear interpolation for short gaps (< 200 ms) to preserve temporal continuity. For longer gaps, missing values were imputed using the column-wise mean calculated across the remaining valid samples within the same trial and muscle channel. This ensured consistency while minimizing bias in feature distributions. All signals were then standardized to zero mean and unit variance prior to feature extraction.

The steps included: (i) Signal cleaning: Filtering and artifact removal; (ii) Missing value imputation: To ensure data continuity; (iii) Feature scaling: Standardization to zero mean and unit variance; (iv) Categorical encoding: One-hot encoding of participant skill levels (novice, intermediate, expert). To streamline feature engineering, data from each muscle group were exported into individual CSV files, enabling structured and modular input into the machine learning pipeline. The dataset analyzed and codes generated during the current study are available in the GitHub repository, https://github.com/rahulsongra/Explainable_AI_Surgical_Skill .

Data splitting and leakage control

To avoid data leakage across tasks and trials from the same individual, we performed a subject-wise split: all trials from a given participant (across all tasks) were assigned exclusively to either the training or the test set. We used an 80/20 subject-wise split and conducted grouped cross-validation on the training data (GroupKFold with participant ID as the grouping variable) for hyperparameter selection, ensuring that no participant appeared in more than one fold. This strategy prevents inflating performance due to user-specific execution signatures and addresses the reviewer’s concern about task-level leakage.

Machine learning and classification approach

We implemented a multi-class classification framework to distinguish among novice, intermediate, and expert skill levels, thereby avoiding the oversimplification of binary models. The feature set comprised (i) time- and frequency-domain characteristics of sEMG signals, (ii) kinematic parameters derived from accelerometer data, and (iii) nonlinear dynamical features such as entropy measures, Lyapunov exponents, correlation dimension, and Hurst exponent. Features were grouped by muscle origin, and recursive feature elimination (RFE) was applied to reduce dimensionality and improve interpretability.

To ensure robust evaluation, all trials from a given participant were assigned exclusively to either the training or test set (80/20 subject-wise split). Performance was quantified using multiple metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and area under the ROC curve (AUC), with class-wise metrics reported to highlight differences across expertise levels.

Machine learning models and hyperparameter optimization

Four supervised machine learning models were implemented: (i) Support Vector Machine (SVM): Trained with an RBF kernel to capture nonlinear relationships between muscle activity and skill level. Preliminary tests with polynomial and linear kernels yielded lower accuracy. Hyperparameters (C, gamma) were tuned via grid search in grouped cross-validation. Probabilistic outputs were enabled for ROC analysis, and RFE was used to refine the feature set. (ii) Random Forest: Implemented with 100 decision trees, Gini impurity, and no depth restriction. Preliminary experiments suggested that default hyperparameters provided competitive accuracy, with tuning performed via grid search. (iii) XGBoost: Configured with a learning rate of 0.3, maximum depth of 6, and 100 boosting rounds. Grid search was used to optimize key parameters (eta, depth, subsampling). Performance was evaluated using multi-class log loss (mlogloss). (iv) Gaussian Naïve Bayes: Trained on standardized features with missing values imputed by column means. The smoothing parameter (α) was varied between 0.1 and 1.0. RFE was applied to select the 10 most predictive features. All models were trained using the same subject-wise 80/20 split, and grouped cross-validation ensured no participant contributed data to both training and validation folds, thereby eliminating task- or user-level leakage.

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): To improve transparency and clinical interpretability, we applied two complementary XAI methods: (i) SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP): Used for both global and local interpretability. Globally, SHAP identified the most consistently influential features (e.g., Lyapunov exponents, entropy measures). Locally, SHAP force plots showed how individual features such as extensor carpi ulnaris activity or triceps suppression contributed to predictions. Importantly, SHAP also captured feature interactions, revealing synergistic effects between muscle groups. (ii) Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME): Provided rapid, instance-level explanations by perturbing input features and fitting interpretable surrogate models. LIME highlighted, for example, how increased thenar eminence activity could disproportionately influence an “expert” classification. While less effective than SHAP at modeling interactions, LIME offered intuitive case-specific insights.

Together, SHAP and LIME provided a comprehensive interpretability framework: SHAP suited for global attribution in tree-based models (Random Forest, XGBoost), and LIME extending interpretability across all classifiers, including SVM and Naïve Bayes. This dual approach enhanced confidence in model validity and linked classifications to meaningful neuromuscular biomarkers.

Software and Hardware: All preprocessing and model training were conducted in Python 3.9, using scikit-learn (v1.2), XGBoost (v1.7), SHAP (v0.41), and LIME (v0.2). Analyses were performed on a workstation running Ubuntu 20.04 LTS with an Intel Core i7-11700 CPU (8 cores, 2.5 GHz) and 32 GB RAM, without GPU acceleration. Reproducibility was ensured by fixing random seeds, and all code is available at GitHub.

Variability within the intermediate group

We did not stratify PGY levels within the intermediate group due to small sample sizes per year. However, we observed greater within-group variability in residents compared to novices and experts, reflected in wider feature distributions (e.g., entropy, LyE). This suggests that the intermediate group spans a transitional spectrum between novices and experts, which may partly explain the overlap seen in PCA/t-SNE plots (Figs. 2 and 3). All results reported below reflect subject-wise train/test separation and grouped coefficient of variation (CV) to preclude per-user leakage.

Classification performance across models

Support vector machine (SVM): The Support Vector Machine (SVM) model achieved a classification accuracy of 59%. Table 1 presents class-wise performance metrics, indicating moderately balanced performance across all skill levels, with the highest F1-score observed for the Expert class (F1 = 0.62). The overall sensitivity and specificity were 59% and 79%, respectively, with a Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.38 and an AUC of 0.76 (Table 2).

Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) were used to visualize class separability in the feature space (Figs. 2 and 3). The confusion matrix (Fig. 4) illustrated some overlap, particularly between Intermediate and Novice categories. Feature importance analysis using SHAP identified the ten most informative predictors for the SVM classifier (Fig. 5), and ROC curves (Fig. 6) further demonstrated that the model performed best in distinguishing the Expert group.

The PCA and t-SNE plots showed only modest class separability compared to approaches using video and kinematics alone14. This likely reflects the limited sample size and the noisier nature of EMG signals compared to video features. Nonetheless, nonlinear biomarkers extracted from EMG and accelerometry still contributed valuable information, as evidenced by their high feature importance in ensemble models.

Random forest and XGBoost

Both ensemble models outperformed the SVM and Naïve Bayes classifiers. Random Forest achieved an overall accuracy of 71.6%, with an F1-score of 71.4% and MCC of 0.575. XGBoost slightly exceeded this performance with 72.5% accuracy, an F1-score of 72.4%, and MCC of 0.589 (Table 3). Class-wise analysis (Table 4) showed that both models performed best in predicting the Expert class (F1 = 0.78), followed by Novice and Intermediate groups.

ROC curves for both models demonstrated strong discriminative power, with clear class separation across all three skill levels (Fig. 7).

Naïve Bayes

The Naïve Bayes classifier achieved an overall accuracy of 54.7%, with sensitivity of 48.8%, specificity of 74.5%, MCC of 0.25, and AUC of 0.65 (Tables 5 and 6). While the Intermediate group had the best performance (F1 = 0.59), the Expert group had a low recall (0.26), indicating frequent misclassifications (Fig. 8). The confusion matrix and SHAP-based feature importance (Fig. 9) highlighted entropy and dynamical complexity metrics as major contributors. The ROC curves for all three classes are shown in Fig. 10.

Explainable AI analysis

To enhance interpretability, SHAP and LIME were applied to all models, providing feature attribution at both global and local levels.

Naïve Bayes explainability and feature attribution

SHAP analysis revealed the top 10 most important features for Naïve Bayes classification (Fig. 11), including Approximate Entropy, Sample Entropy, and various Lyapunov exponent measures. These features consistently drove classification performance across skill levels. LIME analysis (Fig. 12) confirmed similar patterns, highlighting the local importance of entropy-related features in specific instances. ROC curves reconfirmed moderate predictive performance (AUC = 0.65; Fig. 13), and SHAP force plots illustrated instance-level feature contributions (Fig. 14).

The class-wise precision, recall, and F1-scores for the Naïve Bayes classifier with integrated XAI interpretation are presented in Table 7, reaffirming the model’s stronger performance for Intermediate and Novice classes compared to the Expert group. Additionally, the confusion matrix (Table 8) provides detailed insight into the distribution of predicted versus true labels, showing that Expert samples were frequently misclassified as Intermediate.

Random forest interpretability

The Random Forest model achieved 60% accuracy with a ROC-AUC of 0.97, indicating excellent discriminative capability despite lower recall for the Expert class (12%) (Table 9). SHAP (Fig. 15) and LIME (Fig. 16) consistently identified Mean_Long_LyE, Correlation Dimension, and Generalized Hurst Exponent as top predictors. The ROC curve is shown in Fig. 17, and SHAP summary plots in Fig. 18 highlighted robust feature importance patterns across skill levels.

XGBoost interpretability

XGBoost achieved 59% classification accuracy with a ROC-AUC score of 0.96. Feature attribution using SHAP (Fig. 19) and LIME (Fig. 20) pointed to similar dominant features, with XGBoost placing greater emphasis on Mean_Generalized_Hurst_Exp and DFA-related metrics. Despite its overall accuracy, the Expert class had low recall (16%), similar to Random Forest (Table 10). ROC performance is shown in Fig. 21, and the SHAP summary plot for XGBoost is presented in Fig. 22.

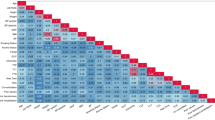

Comparative feature insights across models

Across Random Forest and XGBoost classifiers, nonlinear dynamic features including Lyapunov exponents (e.g., Mean_Long_LyE), Correlation Dimension, and entropy measures (e.g., Approximate Entropy) consistently emerged as the most predictive indicators of surgical skill level. Notably, Random Forest favored features like Mean_Wolf_LyE and Sample Entropy, while XGBoost placed higher weight on Hurst exponent metrics such as Mean_DFA_alpha and Mean_Generalized_Hurst_Exp. These findings suggest that each model leveraged different yet plausible dynamics to differentiate skill levels, underscoring the robustness of the selected features.

Summary of model performance

Among all models, XGBoost (accuracy = 72.5%, F1 = 72.4%, MCC = 0.589) and Random Forest (accuracy = 71.6%, F1 = 71.4%, MCC = 0.575) achieved the best performance. In comparison, SVM (accuracy = 59%, MCC = 0.38) and Naïve Bayes (accuracy = 54.7%, MCC = 0.25) performed less well. Thus, the ensemble models demonstrated a 13–18% absolute improvement in accuracy and stronger correlation coefficients, confirming their robustness in distinguishing skill levels. SHAP and LIME provided transparent interpretations across all models, enabling identification of key muscle-based and dynamical biomarkers. These insights pave the way for personalized, feedback-driven surgical training systems based on wearable sensor data.

Discussion

Our results highlight that nonlinear movement features captured from EMG and accelerometer signals provide critical information to distinguish surgical skill levels. In particular, metrics derived from chaos theory and complexity analysis – including the largest Lyapunov exponent, approximate entropy (ApEn), correlation dimension, and Hurst exponent – emerged as key differentiators between expert, intermediate, and novice surgeons. These features quantify subtleties of movement variability and neuromuscular control that linear metrics or simple performance measures might overlook3. For example, the largest Lyapunov exponent (LyE) reflects the local dynamic stability of the motion; we observed that expert surgeons tended to have lower LyE values (indicating more stable, less chaotic movement trajectories), whereas novices showed higher LyE consistent with more chaotic or erratic motion patterns15. This finding aligns with prior observations that experienced surgeons perform surgical motions with less chaos than novices15, suggesting that experts maintain smoother and more self-stabilizing movements even during complex robotic tasks.

In contrast, entropy-based measures of the acceleration signals (such as ApEn and its multiscale variants) were higher in the expert group, indicating greater signal complexity. Increased entropy in a physiological time series is generally associated with a more adaptable and richly connected neuromuscular control network developed through practice16. In our context, experts’ movements exhibited high complexity across multiple time scales, whereas novices’ movements were more regular or stereotyped. This is consistent with the concept of optimal movement variability, wherein skilled performers display a complex but controlled motion pattern: their movements are not purely repetitive or rigid, but instead contain nuanced fluctuations that enhance adaptability17. Indeed, previous research in motor control has noted that expert performers can be simultaneously less variable in outcomes yet more complex in their movement patterns18. Our findings reinforce this idea – experts achieved the surgical tasks with stable precision while still exhibiting complex dynamics, whereas novices often either froze degrees of freedom (resulting in overly regular, low-complexity signals) or produced erratic corrections (high short-term variability but without useful multi-scale structure).

Notably, the correlation dimension (CD) of the acceleration signals further supported these differences. The CD – a fractal measure of the dynamical degrees of freedom in the movement – was generally higher for expert surgeons, implying that experts engaged more coordinated degrees of freedom during the task3. In practical terms, an expert’s motor strategy might involve a broader range of joint motions and muscle synergies (increasing the effective dimensionality of the movement pattern), whereas novices tend to constrain or couple their movements, yielding lower-dimensional (more rigid) patterns. This interpretation aligns with the well-established progression in skill acquisition where novices initially restrict movement degrees-of-freedom and experts gradually release them, enabling more fluid and adaptive coordination19. Indeed, our EMG analyses showed that expert surgeons had greater fluctuations in muscle activation (RMS variability) during certain tasks than novices, reflecting a deliberate exploration of different motor strategies and a larger repertoire of muscle usage3. Such “good variability” in experts is indicative of flexible motor control and the ability to adjust on the fly, whereas novices’ lower variability can signify a lack of adaptability or a one-size-fits-all strategy. The Hurst exponent, which measures long-range temporal correlations in the signal, provides another lens on these differences. Although we observed only modest differences in Hurst exponent between groups, there was a trend suggesting that expert movement signals had more persistent long-term correlations (H closer to 0.5–1.0) whereas novices exhibited more anti-persistent or random walk characteristics. A higher Hurst exponent in experts’ data could signify more predictable, smooth trends in their movements (once a movement trajectory is initiated, an expert continues it with steady control), whereas a lower exponent in novices might reflect frequent direction changes or corrections, consistent with less efficient motor planning. Together, these nonlinear features portray a coherent picture: expert surgeons’ motor outputs are dynamically stable, complex, and richly structured, whereas novices’ movements are prone to instability and either overly simplistic or noisy. These insights extend beyond conventional performance metrics, emphasizing that skill learning manifests in the neuromuscular dynamics – practiced surgeons achieve an optimal balance of smoothness and complexity in their motions. Our findings align with prior work evaluating muscle activity during surgical tasks. Soto Rodriguez et al.9 demonstrated that EMG and accelerometry could differentiate laparoscopic skill levels during pattern-cutting tasks. Rodrigues Armijo et al.20 compared EMG-based fatigue between laparoscopic and robotic practice, highlighting ergonomic differences. Building on these studies, our approach integrates EMG-derived nonlinear biomarkers with explainable machine learning to provide skill-level classification and interpretable feedback.

While ensemble models like Random Forest and XGBoost performed best overall, our Support Vector Machine (SVM) model yielded moderate classification accuracy. We used an RBF (Radial Basis Function) kernel due to its strength in modeling nonlinear relationships commonly seen in neuromuscular data. Preliminary testing with linear and polynomial kernels resulted in lower performance, suggesting the superiority of the RBF kernel in this context. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that additional kernel tuning or the use of hybrid or adaptive kernel methods may yield further gains in classification performance, especially for distinguishing between adjacent skill groups such as novice and intermediate. Importantly, the contribution of these nonlinear features were borne out by their prominence in the classification models. Across the machine learning classifiers (SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Naïve Bayes), features like Lyapunov exponent, entropy measures, and correlation dimension consistently ranked among the most informative predictors for skill level. In fact, the inclusion of these nonlinear variability metrics significantly improved classification accuracy and separability of the three skill groups3,4. This underscores that objective skill assessment benefits from looking beyond linear or time-domain features: by capturing aspects of movement variability, predictability, and complexity, we can better discern the subtle differences between an intermediate trainee and a true expert. Our study’s findings corroborate prior work showing that wearable sensor data on movement and muscle activity can detect subtle differences in skill performance that human observers or simple metrics might miss3,4. Our accuracy (~ 72%) is lower than state-of-the-art deep learning methods such as transformer-based frameworks21, which leverage video and kinematic data. However, our framework emphasizes interpretability and transparency by integrating sEMG and accelerometer-derived neuromuscular biomarkers with SHAP/LIME explanations. While deep models may achieve higher raw accuracy, their black-box nature limits direct feedback for surgical training. Our work contributes complementary insights by identifying biomechanically meaningful markers of expertise.

Notably, while our use of nonlinear dynamical features with EMG and accelerometry provides new interpretability and robustness, recent advancements in HMI-based manipulation analysis have also shown potential in capturing motor skill nuances. For example, Li et al. employed nonlinear sEMG spectral features for simultaneous motion classification and force estimation, suggesting a potential path toward integrating control and feedback features10. Bimbraw et al. demonstrated ultrasound imaging as a non-invasive method for estimating skill and force, pushing the boundary of what wearable HMIs can detect in real time11. Compared to these approaches, our method prioritizes transparency and interpretability, emphasizing model explainability (via SHAP/LIME) and biomechanically grounded features like Lyapunov exponents and entropy to enhance clinical trust and feedback utility.

The nonlinear features, in particular, quantify the underlying neuromuscular behavior (e.g. feedback control loops and adaptability) and thus serve as sensitive markers of expertise. Biomechanically, a lower Lyapunov exponent in an expert reflects greater ability to dampen unwanted fluctuations (stability), while higher entropy and fractal dimension reflect a controlled versatility in their movements. Neurophysiologically, these differences may stem from years of training leading to more refined sensorimotor integration – experts can exploit feed-forward and feedback pathways to correct movements seamlessly, resulting in signals that appear complex yet not chaotic. In novices, the lack of ingrained motor programs may result in either hesitancy (rigid, low-complexity patterns) or over-correction (high instability), both of which are captured by the above metrics. Thus, the nonlinear movement features not only statistically differentiate skill levels but also map to meaningful qualities of motor control – namely smoothness, stability, variability, and adaptability – that characterize surgical expertise.

Insights from explainable AI (SHAP and LIME)

While the classification models provided overall accuracy in distinguishing skill groups, the integration of explainable AI (XAI) techniques – specifically SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) – allowed us to delve deeper into how the models made their decisions. These post-hoc explanation tools revealed nuanced, class-specific patterns of feature importance that were not readily apparent from conventional performance metrics or aggregate feature importances alone. For instance, the global SHAP analysis showed that certain features preferentially contributed to identifying one class over the others. Approximate entropy of the accelerometer signals emerged as a strong indicator for novice performance in our models: high ApEn values tended to push the model prediction toward the novice class, suggesting that excessive irregularity in movement was a hallmark of lower skill. In contrast, the correlation dimension and Hurst exponent features had positive SHAP contributions for predicting the expert class – higher values of correlation dimension (reflecting greater movement complexity/DOF) and moderately high Hurst values (more persistent control patterns) were often necessary for a trial to be classified as expert. These class-specific insights were obscured when looking at the model’s overall feature importance; the XAI approach thus illuminated that, for example, entropy-related features were crucial to catching novice-level performances, whereas fractal and stability features were more influential for distinguishing true experts. Such distinctions are invaluable for interpreting model behavior: they indicate that the machine learning classifiers essentially learned physiologically meaningful rules, e.g., “if a surgeon’s movement signal is highly chaotic and unpredictable, label as novice,” or “if the movement pattern shows high complexity and stability, label as expert.” Identifying these learned rules gives us confidence in the model’s validity and suggests that the algorithm’s criteria align with theoretical expectations of skillful vs. unskillful movement patterns.

Furthermore, SHAP dependence plots in our analysis hinted at important feature interactions. For example, the influence of approximate entropy on predicting intermediate skill levels depended on the Hurst exponent: moderate ApEn values contributed to an intermediate classification only when accompanied by a certain range of Hurst exponent, implying that the model picked up on an interaction where intermediate surgeons exhibit a mix of moderate irregularity and specific temporal correlation structure. Such an interaction might correspond to the idea that intermediates have overcome the extreme erraticness of novices (lower ApEn than novices) but have not yet developed the full long-range consistency of experts (different Hurst signature). Local explanations with LIME further reinforced these interpretations by allowing case-by-case examination. For instance, for one expert surgeon’s trial that was misclassified as intermediate, LIME’s feature-weighted explanation showed that in that trial the Lyapunov exponent was unusually high and the ApEn was lower than typical expert profiles. These factors, which deviated from the model’s learned “expert” signature, swayed the classifier toward the intermediate label. In other words, LIME pinpointed that this particular expert trial lacked the expected stability and complexity, illustrating why the model was uncertain. Such granular analyses are extremely useful: they not only identify which features led to an error but also suggest why those feature values might have occurred (e.g., an expert having a momentarily irregular performance, perhaps due to trying a different technique or encountering a difficulty in that trial).

By leveraging SHAP and LIME, we were able to translate the model’s internal logic into human-understandable insights. This approach aligns with the growing emphasis on interpretable machine learning in biomedical applications – the goal is not just to achieve high accuracy, but also to ensure the decision-making process is transparent and trusted. In the context of surgical skill evaluation, such transparency is vital if automated systems are to be accepted by educators and clinicians. Our use of XAI methods resonates with recent efforts to provide personalized feedback in surgical training using AI. For example, other researchers have employed interpretability techniques to highlight which portions of a surgical motion sequence most influenced a skill score22. Similarly, our SHAP and LIME analyses allowed us to identify the specific feature patterns characteristic of each skill level. This means our model does more than output a skill rating – it also points to why a surgeon was rated as such, whether it be due to their movement smoothness, consistency, or variability profile. Such feedback can be directly communicated to trainees: an algorithm might report, for instance, “High movement variability (high Lyapunov exponent) was a strong contributor to this assessment – consider practicing to improve the stability of your motions.” In summary, the explainable AI component of our study provided new insights that were not evident from black-box model outputs alone, confirming that the models learned credible skill-related differences and uncovering the subtleties of feature importance and interplay that define each skill category.

Clinical and training implications

Our findings carry several important implications for clinical skill assessment and surgical training. First, the ability to objectively classify surgical expertise using wearable sensors and advanced analytics addresses a known gap in surgical education. Traditionally, surgical skill evaluation has relied on expert observation or global rating scales, which can be subjective and resource-intensive23. By demonstrating that sEMG and accelerometer data can robustly distinguish novice, intermediate, and expert surgeons3, this study lays the groundwork for automated, real-time skill assessment tools24. The nonlinear movement features identified through our explainable machine learning framework demonstrate significant translational potential for both surgical skill training and clinical motor assessment. In particular, dynamical metrics such as entropy, Lyapunov exponents, and correlation dimension – which quantify movement irregularity, stability, and complexity, respectively – emerged as sensitive indicators of motor control proficiency. These measures provide an objective window into the quality of movement: for example, experts’ motions tended to exhibit distinct entropy and stability profiles, reflecting more refined neuromotor control. Integrating such features into training curricula can enable quantitative performance tracking beyond traditional metrics, helping educators and clinicians detect subtle improvements or regressions in skill. Importantly, the use of an explainable ML model (via SHAP and LIME) means that the contributing features for skill classification are transparent. Although our classification accuracies (54.7–72.5%) are modest compared to black-box deep learning models using video or kinematics, this study provides unique contributions. By leveraging sEMG and accelerometer data, we capture neuromuscular biomarkers of expertise that complement motion-based metrics. The integration of explainable AI techniques (SHAP, LIME) ensures that skill classifications are interpretable and linked to meaningful motor-control constructs such as stability, adaptability, and complexity. This transparency distinguishes our framework from higher-accuracy but opaque models, enabling actionable feedback for trainees. Thus, even with accuracies below 80%, our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of an interpretable, wearable-sensor–based framework for surgical skill assessment. This interpretability allows instructors and clinicians to understand which movement attributes (e.g., predictability or adaptability) distinguish expert-level performance, facilitating targeted feedback. Furthermore, these insights lay the groundwork for real-time, sensor-based feedback systems in which wearable or simulator sensors compute nonlinear feature values on the fly. Trainees or patients could then receive immediate, data-driven feedback – for instance, alerts when their movement pattern becomes overly irregular – thereby closing the loop between assessment and intervention in both surgical education and rehabilitation settings.

Limitations and future directions

Despite promising results, this study has several limitations. The sample size was small (n = 26), with limited representation in the expert group, which may have reduced the model’s ability to generalize across skill levels. Additionally, data were collected in a controlled, simulated setting and focused solely on sEMG and accelerometer signals, potentially overlooking other relevant dimensions of surgical skill. Mean-value imputation for EMG signal gaps > 200 ms can dampen variance and alter short-range temporal dependencies in physiological time series. While long dropouts were uncommon in our data, future work will replace this step with band-limited, shape-preserving interpolation for short or medium gaps and window-level exclusion for long gaps, accompanied by sensitivity analyses of feature and model robustness. A limitation of our study is the heterogeneity of the intermediate group (PGY 1–5). These residents vary widely in robotic surgical experience, and intra-class variability may have blurred distinctions between novices, intermediates, and experts. While we treated PGY 1–5 as a single intermediate group to maintain statistical power, future work with larger cohorts should stratify residents by training year or cumulative robotic case volume to better capture skill progression. Another limitation of this study is that we did not formally assess participants’ musculoskeletal history (e.g., recent injuries or surgeries), which could influence motor performance and EMG signals. Future studies will incorporate explicit musculoskeletal screening to minimize such confounding factors. And future studies with larger datasets should incorporate dedicated validation sets and nested cross-validation to enable more robust hyperparameter optimization. Although SHAP and LIME enhanced interpretability, their computational demands limit real-time application.

Future work should prioritize expanding the dataset with more balanced participant groups and incorporating additional modalities such as video, kinematics, or physiological measures. Real-time integration of interpretable models could enable adaptive feedback during training. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are needed to validate whether the identified nonlinear biomarkers reliably track motor learning over time and generalize to real surgical environments. These enhancements will strengthen model robustness and support broader clinical translation.

Data availability

The dataset and feature extraction and machine learning codes are available at GitHub link [https://github.com/rahulsongra/Explainable_AI_Surgical_Skill](https:/github.com/rahulsongra/Explainable_AI_Surgical_Skill) . These can also be accessed by corresponding author.

References

Stulberg, J. J. et al. Association between surgeon technical skills and patient outcomes. JAMA Surg. 155, 960–968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.3007 (2020).

Birkmeyer, J. D. et al. Surgical skill and complication rates after bariatric surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 1434–1442. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1300625 (2013).

Soangra, R., Sivakumar, R., Anirudh, E. R., Reddy, Y. S. & John, E. B. Evaluation of surgical skill using machine learning with optimal wearable sensor locations. PLoS One 17, e0267936. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267936 (2022).

Soangra, R. et al. Beyond efficiency: Surface electromyography enables further insights into the surgical movements of urologists. J. Endourol. 36, 1355–1361. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2022.0120 (2022).

Carciumaru, T. Z. et al. Systematic review of machine learning applications using nonoptical motion tracking in surgery. npj Digit. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01412-1 (2025).

Xu, J. et al. A deep learning approach to classify surgical skill in microsurgery using force data from a novel sensorised surgical glove. Sensors. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23218947 (2023).

Nguyen, X. A., Ljuhar, D., Pacilli, M., Nataraja, R. M. & Chauhan, S. Surgical skill levels: Classification and analysis using deep neural network model and motion signals. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 177, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.05.008 (2019).

Brandenburg, J. M., Muller-Stich, B. P., Wagner, M. & van der Schaar, M. Can surgeons trust AI? Perspectives on machine learning in surgery and the importance of eXplainable artificial intelligence (XAI). Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 410, 53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-025-03626-7 (2025).

Soto Rodriguez, N. A. et al. Objective evaluation of laparoscopic experience based on muscle electromyography and accelerometry performing circular pattern cutting tasks: A pilot study. Surg. Innov. 30, 493–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/15533506231169063 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Simultaneous hand/wrist motion recognition and continuous Grasp force Estimation based on nonlinear spectral sEMG features for transradial amputees. Biomed. Signal Process. Control https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105044 (2023).

Bimbraw, K. et al. Simultaneous Estimation of manipulation skill and hand grasp force from forearm ultrasound images (2025).

Yibulayimu, S. et al. An explainable machine learning method for assessing surgical skill in liposuction surgery. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 17, 2325–2336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-022-02739-4 (2022).

Hermens, H. J., Freriks, B., Disselhorst-Klug, C. & Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 10, 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1050-6411(00)00027-4 (2000).

Wu, J. Y., Tamhane, A., Kazanzides, P. & Unberath, M. Cross-modal self-supervised representation learning for gesture and skill recognition in robotic surgery. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 16, 779–787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-021-02343-y (2021).

Ohu, I., Cho, S., Zihni, A., Cavallo, J. A. & Awad, M. M. Analysis of surgical motions in minimally invasive surgery using complexity theory. Int. J. BioMed. Eng. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijbet.2015.066966 (2015).

Richman, J. S. & Moorman, J. R. Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 278, H2039–H2049. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2039 (2000).

Gölz, C. et al. Improved neural control of movements manifests in Expertise-related differences in force output and brain network dynamics. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2018.01540 (2018).

López-Fernández, M., Sabido, R., Caballero, C. & Moreno, F. J. Relationship between initial motor variability and learning and adaptive ability. A systematic review. Neuroscience 565, 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2024.10.052 (2025).

Johnson, R. R. et al. Identifying psychophysiological indices of expert vs. novice performance in deadly force judgment and decision making. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 512. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00512 (2014).

Rodrigues Armijo, P., Huang, C. K., Carlson, T., Oleynikov, D. & Siu, K. C. Ergonomics analysis for subjective and objective fatigue between laparoscopic and robotic surgical skills practice among surgeons. Surg. Innov. 27, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1553350619887861 (2020).

Zheng, Y. & Majewicz-Fey, A. In 2024 International Symposium on Medical Robotics (ISMR). 1–8.

Ismail Fawaz, H., Forestier, G., Weber, J., Idoumghar, L. & Muller, P. A. Accurate and interpretable evaluation of surgical skills from kinematic data using fully convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 14, 1611–1617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-019-02039-4 (2019).

Close, M. F. et al. Subjective vs computerized assessment of surgeon skill level during mastoidectomy. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 163, 1255–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820933882 (2020).

Lavanchy, J. L. et al. Automation of surgical skill assessment using a three-stage machine learning algorithm. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84295-6 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to collaborators “Pengbo Jiang , Daniel Haik , Perry Xu , Andrew Brevik, Akhil Peta , Shlomi Tapiero , Jaime Landman , Emmanuel John , Ralph V Clayman”.

Funding

This research partially supported students in learning machine learning techniques and related libraries. The research work was a training platform for funded project by “Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, grant number 1R15HD110941-01” at National institute of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H. wrote all machine learning codes. J.S. reviewed all codes for accuracy and assisted A.H. in programming. R.S. and V.K. carried out revisions of Methods and Results section and wrote manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soangra, R., Hossain, A., Sonagra, J. et al. Explainable machine learning using EMG and accelerometer sensor data quantifies surgical skill and identifies biomarkers of expertise. Sci Rep 16, 1207 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30894-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30894-6