Abstract

Exposure to ambient air pollutants, specifically ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ultrafine, fine or coarse particulate matter (PM0.1, PM2.5, and PM10), has been linked to a number of adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease. Changes in immune response may be a key mechanism underlying these effects. Within the California Teachers Study cohort, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 1,898 women to assess the associations between exposure to O3, NO2, PM0.1, PM2.5, and PM10 and 15 immune markers measured from serum samples collected in 2015. Daily residential exposures to O3, NO2, PM0.1, PM2.5, and PM10 were estimated by a validated chemical transport model and averaged over 12-, 3-, and 1-month periods prior to blood draw. Fifteen immune markers (categorized as quartiles) were estimated per interquartile range (IQR) of air pollutant exposures using multivariable ordinal logistic regressions adjusted for age, body mass index, and respective pollutants. Immune markers were also grouped into immune pathways (pro-inflammatory/macrophage activation, B-cell activation, and T-cell activation). After applying Bonferroni correction, elevated exposure to O3 levels at all three exposure windows were associated with elevated circulating levels of IL-1β (interleukin-1 beta), IL-8 (interleukin 8), sTNFR2 (soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 2), and sgp130 (soluble glycoprotein 130). Elevated O3 at 3- and 1-month periods were associated with increased levels of sCD27 (soluble cluster of differentiation 27) and BAFF (B-cell activating factor). In pathway analyses, O3 was consistently and significantly associated with the pro-inflammatory/macrophage activation pathway (12-month OR = 1.49, 3-month OR = 1.57, 1-month OR = 1.54) and with B-cell activation at all three exposure windows (12-month OR = 1.24, 3-month OR = 1.53, 1-month OR = 1.41). NO2 was positively associated with TNFα at the 3- and 1-month exposure windows. For the PM size fractions, sporadic, mainly inverse, associations with immune markers were observed. Elevated O3 exposure up to one year prior to blood draw was associated with elevated immune markers related to pro-inflammatory response, macrophage activation, and B cell activation. These findings suggest potential immunologic pathways linking air pollution to adverse health outcomes in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exposure to ambient air pollutants, including tropospheric ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and particulate matter (PM; PM0.1 [ultrafine particles, less than 0.1 µm], PM2.5 [fine particles, less than 2.5 µm], and PM10 [coarse particles, less than 10 µm]), has been linked to a number of adverse health outcomes, including cardiovascular and respiratory diseases1,2. NO2 is an irritant gas that is created from the atmospheric reaction of NO emitted from combustion processes1,3,4. According to the American Lung Association, the largest contributors of ambient NO2 in urban areas are transportation-related, including emissions from trucks, buses and cars4. NO2 and NOx react in the presence of sunlight in the atmosphere to form secondary pollutants, such as O31,4,5. PM is both a primary and secondary pollutant. Primary PM is directly emitted from natural sources, such as wildfires and windblown dust, as well as anthropogenic sources, such as combustion and resuspended road dust3. Secondary PM is formed from precursor gases, including NOx and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), through complex chemical reactions. Although regulatory efforts by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have led to declines in NO2, O3, and PM2.5 over recent decades6,7, epidemiological studies continue to report adverse health outcomes even at low ambient concentrations1,3,8,9,10.

The primary route of human exposure to air pollutants is through inhalation1,3,4. Ultrafine particles can penetrate deep into the lung and enter the bloodstream where they may trigger inflammatory response by releasing inflammatory mediators2,8,14. Inflammation can thus occur locally in the lungs and systemically once the pollutant enters the bloodstream. However, prior epidemiological studies of associations between air pollutants and circulating immune biomarkers have been limited in scope to interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β); prior studies generally do not include or account for multiple air pollutants and are often restricted to short-term exposures15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Moreover, studies of PM0.1 remain scarce, despite growing concern of their potential to elicit the greatest risk to adverse health outcomes due to their small size and ability to penetrate deep into the lung24,25,26,27. Of particular concern is the evidence linking air pollutant exposure to increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, particularly among post-menopausal women who face heightened risks of CVD and stroke11,12. Given that immune system response function also undergoes significant changes during and after menopause, understanding how air pollution influences immune responses in this population during this important time is critical for informing disease prevention efforts13.To address these gaps, we evaluated associations between five major air pollutants (O3, NO2, PM0.1, PM2.5 and PM10) and 15 immune markers and across multiple exposure windows in 1,898 women, most of whom are post-menopausal and have a heightened risk of cardiovascular events such as strokes9,14,28 and for whom pollution-induced immune changes may have heightened clinical relevance. We hypothesized that exposures to pollutants would be associated with elevated inflammatory marker levels.

Methods

Study population

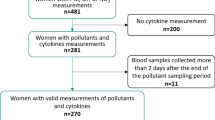

The California Teachers study (CTS) is a prospective cohort study of 133,477 women who were active or recently retired public-school professionals in 1995 and have been followed since for health outcomes. The CTS cohort has been previously described29 and is approved by the Institutional Review Board of City of Hope. Participants provided informed consent at baseline. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. In all, six questionnaires have been administered to CTS participants, and, in 2013–2016, 14,374 participated in a biobanking study (consent was obtained before collection)30. A subset of 1,900 of these participants were selected for inclusion in the present cross-sectional study if they had blood drawn in 2015; to ensure that a sufficient distribution of characteristics and exposures were reflected in our sample, participants were selected with stratified sampling for: socioeconomic status at baseline (SES; in quartiles determined by occupation, and income), geographical residence at baseline (according to 1990 census block groups), race, and PM2.5 estimates. As the goal of this cross-sectional study was to evaluate the associations between air pollutant exposures and immune marker levels, capturing the full range of exposures ensured there would be sufficient statistical power to evaluate all levels of exposure. Two participants were excluded due to missing exposure estimates.

Immune marker measurements

From 7/1/2013 to 8/31/2016, under grant award UM1-CA164917, we collected 14,374 blood samples. Blood samples were shipped overnight to Fisher BioServices (FBS) in Rockville, MD, for processing and storage; 96% of samples were processed at FBS within 24 h of collection (and 99.5% within 27 h); average time from collection to processing was 18 h.

Serum samples processed from whole blood collected were evaluated at University of California, Los Angeles for 15 immune markers by multiplexed immunometric assays (two Luminex panels; R&D Systems) and a Bioplex 200 system (Bio-Rad). Panel 1 included the detection of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 (interleukin-8), IL-10 (interleukin-10), and TNFα. Panel 2 included the detection of BAFF (B-cell activating factor), CCL2 (chemokine ligand 2), CCL17 (chemokine ligand 17), sCD14 (soluble cluster of differentiation 14), sCD25 (soluble cluster of differentiation 25), sCD27 (soluble cluster of differentiation 27), sCD163 (soluble cluster of differentiation 163), sgp130 (soluble glycoprotein 130), sIL6Rα (soluble interleukin 6 receptor subunit alpha), and sTNFR2 (soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 2). These immune markers have been identified as contributors in the following immune pathways: (1) pro-inflammatory/macrophage activation: IL-1β, IL-6, sIL-6Rα, IL-8, TNFα, sTNFR2, CCL2, sCD14, sCD163, and sgp130; (2) B-cell activation: IL-10, sIL-6Rα, IL-6, sgp130, CD27, and BAFF; and 3) T-cell activation: CCL17 and sCD25. The cytokine units of measurement are in pg/ml. The laboratory assays included 5% QC replicates and duplicate samples. All assays were conducted blinded and in a single batch using the same reagent production lot to eliminate seasonal and batch variations and were done in the same laboratory (Epeldegui lab, University of California, Los Angeles) to eliminate variation in reagents31,32. Additionally, all immune markers were evaluated individually after finding minimal evidence of correlation among them (via Spearman coefficients) (Supplemental Table S1).

Air pollution exposures

Air pollution exposures were estimated based on geocoded addresses of CTS participants from 2014–2015. Daily air pollution exposures were estimated at 4 km spatial resolution using the University of California at Davis / California Institute of Technology (UCD/CIT) chemical transport model33. Briefly, the UCD/CIT model was configured to cover regions containing more than 93% of California’s population, including over 100,000 CTS participants9. The UCD/CIT model can be configured to use a number of gas-phase chemical mechanisms34. In the current study, the SAPRC11 (Statewide Air Pollution Research Center, 2011) chemical mechanism was used to predict gas-phase pollutant concentrations based on the reliable performance of this mechanism in California35. Model performance statistics met the goals and criteria for Chemical Transport Model (CTM) applications36. Raw CTM predictions are an independent estimate of pollutant concentrations based on fundamental physics and chemistry equations that do not depend on the measured ambient values. The estimates are based on emissions inventories developed through observations of activities that release pollutants, chemical mechanisms developed based on detailed reactions that occur in the atmosphere, transport calculations that account for advection, turbulent diffusion, and vertical mixing, dry- and wet-deposition calculations that remove particles from the atmosphere, nucleation calculations that create condensed phase material from gas-phase precursors, condensation/evaporation calculations that transfer semivolatile compounds between the gas phase and existing liquid/solid phases on particles, thermodynamic calculations that predict the vapor pressure of semivolatile compounds at the surface of each particle, and coagulation calculations that combine particles that collide due to random motion in the atmosphere. Bias in the CTM calculations can occur for various reasons, such as inaccurate wind fields/atmospheric boundary layer height, incomplete emissions estimates, etc. In the current study, we analyzed the bias in the CTM calculations through a comparison to regulatory monitors that measured PM2.5 mass and chemical composition. We used a Random Forest Regression (RFR) model to predict the fractional bias (FB) in 24 h average concentrations in grid cells where monitoring data was available. FB is defined as 2(P − O)/(P + O) where P is the prediction and O is the observation in the grid cell of interest. Support variables in the RFR calculations included predicted meteorological parameters, low-cost sensor measurements of PM2.5 mass, satellite observations of aerosol optical depth, and predicted source activity based on source tracers embedded in the CTM calculations. Raw CTM predictions were adjusted using the FB predicted by the RFR method according to the correction factor (2-FB)/(2 + FB). UCD/CIT estimates of daily PM mass (PM0.1, PM2.5 and PM10; µg/m3), O3 (1 h max ppm) and NO2 (24 h average ppm) were assigned to the geocoded residential locations of the CTS participants for the year prior (2014) to the date of their blood draw (2015)9,37. From these daily estimates, different exposure windows were assigned to each participant representing 12-month (long-term), 3-month (short-term), and 1-month (short-term) averages before their blood draw date. Additionally, Pearson coefficients for the pollutants are presented in Supplemental Table S2.

Covariates

Covariates considered included those previously associated with immune markers and/or air pollution9,12,28,33. The most parsimonious model was selected and included age and BMI9,38. For multivariable models, in addition to adjusting for age (continuous) and BMI (categorical; < 25, 25–29, or 30 + kg/m2), O3 and NO2 models were each adjusted for all PMs, and the PM models were similarly each adjusted for O3 and NO2. The addition of temperature (annual averaged similarly to the pollutants) into the multivariable models did not alter magnitude of risk and was not included in final models.

Statistical analyses

Multivariable ordinal logistic regression was used to estimate associations between air pollutant exposures and immune markers (in quartiles). Quartiles were used in order to inform whether the resultant associations were dose-dependent (e.g., increasing exposure with increasing levels of immune markers) or conferred a threshold effect (e.g., increasing exposure associated after certain level or only the highest level of circulating immune markers). Because each pollutant had different units (e.g., O3 is measured as 1-h max ppm whereas NO2 is measured as 24-h average ppm; PMs were measured as 24-h average µg/m3), we scaled the estimates by the interquartile range (IQR) to facilitate comparisons among the exposures. Results are reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) scaled by the IQR of the pollutant. To account for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was applied. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by first removing immune marker outliers (defined as ± 1.5*IQR) and rerunning the models, followed by excluding extreme pollutant values. Although the purpose of evaluating immune markers by quartiles was to assess a dose-dependent response, additional analyses were performed for continuous immune markers (per pg/ml) using linear models as well as applying inverse probability weighting to assess robustness of the results.

Immune markers were further categorized into immune pathways as: (1) pro-inflammatory/macrophage activation: elevated levels of IL-1β, IL-6, sIL-6Rα, IL-8, TNFα, sTNFR2, CCL2, sCD14, sCD163, and sgp130; (2) B-cell activation: elevated levels of IL-10, sIL-6Rα, IL-6, sgp130, CD27, and BAFF; and (3) T-cell activation: elevated levels of CCL17 and sCD25. As previously conducted, pathways were defined by first identifying those with individual immune marker levels above the respective median; of those individuals, participants with the number of elevated immune markers that exceeded the median number of total immune markers in the pathway were defined as expressing the specific immune pathway39. For example, if a participant had elevated levels (dichotomized as above the median) of > 3 immune markers in the B-cell activation pathway, then they were designated in the B-cell activation pathway. To be considered expressing a pro-inflammatory pathway, at least 5 of the immune markers designated in that pathway would need to be elevated (above the median) for each participant. Associations between the exposures and immune pathways (dichotomized as either expressing or not expressing the specific pathway) were also assessed via ORs and 95% CIs and adjusted by age, BMI, and other pollutants. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and data analyses were conducted via the CTS Researcher Platform40.

Results

Study population characteristics

Of the 1,898 participants, 83% were aged 50 years or older, 42% had normal BMI (< 25 kg/m2), half reported NSAID use of > 1/week, most were non-diabetic (86%), and most did not use statins (71%) at blood draw (Supplemental Table S3). As described in the methods section, compared to the general CTS population, our study population derived from the biobanking project reflected the oversampling for more racially, geographically, and economically diverse population. Briefly, 23.3% were non-White participants and the analytic population contained a more diverse group of women; our study population SES Quartile 4 (the most advantageous group) was 28.7% compared to the full CTS cohort SES Quartile 4 of 47.2% (Supplemental Table S3).

Air pollutant and immune marker measurements

Descriptive statistics for the five air pollutant exposures measured in our study are shown in Fig. 1. For visualization and consistency with other studies, estimates for O3 and NO2 were converted to ppb; however, the units of the models remain as estimated (ppm). Overall, there was relatively high consistency between exposures at the 1-month, 3-month and 12-month time periods before blood draw, particularly for O3 and NO2 where the medians were the same for the 3 exposure periods examined (O3 ~ 51 ppb, 1 h max; NO2 ~ 12 ppb, 24 h avg). PM exposures over the 12-months before blood draw had higher medians than 1- and 3-month exposures (PM0.1: 0.80 µg/m3, PM2.5: 9.49 µg/m3; PM10: 10.50 µg/m3). Mean levels were largely consistent with the median, although slightly higher for PMs. Exposures averaged over the 1-month window were more variable, as reflected by their wider ranges.

Distribution of long-term (12-month) and short-term (3-month and 1-month) averages of Ozone (O3; 1 h maximum parts per billion[ppb]), Nitrogen dioxide (NO2; 24 h maximum ppb), PM0.1 (µg/m3), PM2.5 (µg/m3), and PM10 (µg/m3) prior to the respective blood draw date for 1,898 women in the California Teachers Study.

Quantiles and ranges of the immune markers are shown in Table 1. Most immune markers were present at detectable (> LOD) levels; all markers were detected at the 10th percentile.

Air pollutant exposure associations with immune markers

The multivariable ordinal logistic regressions (scaled by IQR) showed consistent associations between O3 exposure and immune markers (Fig. 2, Supplemental Tables S4–S8). Across all exposure windows, higher O3 was statistically significantly associated with increased odds of having higher circulating levels of IL-1β, IL-8, sTNFR2, and sgp130, with additional associations for sCD27 and BAFF at shorter exposure periods. Associations were highest for 12-month exposure for IL-1β (ORQuartile 4 = 1.99, 95% CI = 1.55–2.56, p-trend < 0.0001) and IL-8 (ORQuartile 4 = 2.92, 95% CI 2.30–3.71, p-trend < 0.0001), whereas sTNFR2, sgp130, sCD27, and BAFF showed highest associations at 3- and 1- month exposures (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table S4).

Visual of the associations for exposures (scaled by IQR for 12-month, 3-month, and 1-month prior to date of blood draw) with immune markers (quartiles). Significant associations (ORs) are denoted by color: 1) positive associations = red and pink; 2) inverse associations = dark blue and light blue; 3) p-trend < 0.05 = lighter shades; 4) p-trend < Bonferroni correction p value = darker shades. O3 and NO2 models were adjusted for age, BMI, and all other exposures (Bonferroni correction p value = 0.001). PM models were adjusted for O3 and NO2 (Bonferroni correction p value = 0.002).

By immune pathway (Table 2), O3 was consistently associated with the pro-inflammatory/macrophage activation pathway across all exposure timepoints (12-month OR = 1.49, 95% CI 1.26–1.75; 3-month OR = 1.57, 95% CI 1.34–1.85; 1-month OR = 1.54, 95% CI 1.33–1.80) and for the B-cell activation pathway (12-month OR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.05–1.47; 3-month OR = 1.53, 95% CI 1.30–1.81; 1-month OR = 1.41, 95% CI 1.21–1.65). Associations with the T cell activation pathway were significant at the shorter time periods (3-month OR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.00–1.42; 1-month OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.00–1.38).

Fewer associations were observed with NO2, though a notable positive association was observed with higher levels of TNFα across short term exposure windows (3-month ORQuartile 4 = 1.63, 95% CI 1.22–2.17; 1-month ORQuartile 4 = 1.40, 95% CI 1.07–1.83) (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Table S5).

PMs yielded largely consistent patterns: (1) decreased IL-1β levels at all 3 time points, except a lack of significance at the 3-month period for PM2.5 and PM10, (2) decreased IL-8 levels at all 3 exposure windows for PM0.1 and PM10 but only the 3-month exposure for PM2.5, and (3) decreased TNFα levels for shorter exposure periods for PM2.5 and PM10 size fractions (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Tables S6–S8). P-trends for all associations are presented in Supplemental Table S9. In sensitivity analyses that excluded air pollutant outliers, results were consistent with the original models (Supplemental Tables S10-S14). Analyses of immune markers as continuous outcomes were also consistent with reported immune marker outcomes as quartiles (Supplemental Table S15).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis within the California Teachers Study, we examined the association between exposures to five air pollutants (O3, NO2, PM0.1, PM2.5 and PM10), estimated using a state-of-the-science chemical transport model at the participants’ residences with 15 circulating immune markers assessed from the blood samples of 1,898 participants collected in 2015. We observed two main findings: (1) higher O3 levels across all exposure windows (1-month to 1-year averages prior to blood draw) were associated with increased levels of several circulating immune markers linked to macrophage activation, pro-inflammatory response and B cell activation, including IL-1β, IL-8, sTNFR2, sgp130, sCD27, and BAFF; and (2) higher NO2 exposure was associated with increased levels of TNFα. In contrast, we note inconsistent, inverse associations between PMs and immune markers, specifically IL-1β, IL-8, and TNFα.

Overall, O3 emerged as the most robust exposure eliciting immune responses, with positive associations across multiple immune markers. These findings align with the small number of epidemiologic studies that have linked O3 exposure with higher IL-1β and IL-8 levels, despite differing methods of exposure estimates and immune marker measurements41,42,43. Our study results are also consistent with prior in vitro and in vivo studies showing that O3 exposure increases levels of IL-8 expression44,45,46,47. The observed association between O3 exposure and increased sTNFR2 is consistent with a prior report of increased TNFR2 levels in relation to short-term (1–7 day) O3 exposure48. To our knowledge, the associations of O3 with sgp130, sCD27, and BAFF have not been previously reported in epidemiological studies.

Briefly, IL-1β is released by cells among the innate immune system to drive inflammatory processes49 while IL-8 is released by a variety of immune cells to help activate neutrophils and promote inflammation50. sTNFR2 is a protein that promotes T cell activity to drive pro-inflammatory processes while also suppressing immune activity by preventing TNF-induced cell death51. sgp130 is involved in pro-inflammatory processes by altering T cell differentiation52. sCD27 is a member of the TNF family and is a marker for B cell activation, specifically that of memory B cells53,54. Finally, and similarly to sCD27, BAFF belongs to the TNF family and plays a role in B cell maturation and survival55.

Our a priori delineation of immune pathways supported these individual marker results. Higher O3 levels at all 3 exposure windows was associated with pro-inflammatory/macrophage activation pathway, consistent with experimental in vivo and in vitro studies showing that O3 induces pro-inflammatory gene expression and the subsequent release of inflammatory markers44,45,56,57. Notably this pathway encompasses immune markers regulated by the NFkB pathway, a pro-central mechanism linking air pollution to cardiovascular disease risk through increased thrombosis and atherosclerosis58,59,60,61. Our results also suggested a link between O3 exposure and the B-cell activation pathway, driven by sgp130, sCD27, and BAFF. These novel findings are not yet supported in the current literature and warrant replication in other studies.

The significant associations with IL-1β in our findings are noteworthy due to its established role as an inflammatory mediator in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), including stroke and CVD. In a large, randomized, double-blind trial, an IL-1β antagonist drug, canakinumab, was reported to reduce recurrent cardiovascular events. These findings in conjunction with our reported findings present the possibility that those who are exposed to higher levels of ambient air pollutants, particularly O3, may benefit from pharmaceutical interventions targeting IL-1β to reduce risk of ASCVD62.

We also report associations between increasing NO2 exposure across all 3 exposure windows with higher TNFα levels. These results complement current evidence of in vivo and in vitro studies that show a relationship between elevated TNFα and NO2 exposure63.

Our results for the PMs were contrary to what was expected. Across PMs, there were decreased risk of elevated IL-1β and IL-8 levels at the different exposure windows, and short-term exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 were associated with decreased TNFα. These findings contradict prior work that have shown that exposure to PM is associated with elevated levels of IL-1β and TNFα16,17. It is possible, however, that the discrepant results may be due to the population subset evaluated. Prior reports have suggested associations between PM10 with elevated levels of IL-1β in men, but not women16,17; moreover, associations with IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α were demonstrated in younger populations, versus our population of largely post-menopausal women where baseline inflammation levels may already be higher16,17. It is also possible that PM-mediated damage may be more localized to the lung and/or to the lung macrophages, resulting in a decrease of systemic immune marker production. It has been shown that PM exposure can lead to oxidative stress and impaired immune cell function, specifically of lung macrophages, which can lead to decreased immune marker production64. Additionally, PMs have been shown to accumulate in macrophages within the lung, thus having a local, direct effect on immune responses and cell function, while O3 and NO2 elicit more chronic, systemic immune responses, especially with long-term exposures65,66,67.

Major strengths of our study include the use of multiplex immune marker assays and the use of a state-of-the-science chemical transport model for exposure assessment. Limitations include the cross-sectional design, which precludes establishing temporal relationships, and reliance on residential address-based exposures, which may not capture exposures from work and/or travel. Our study was also nested in an established cohort (CTS) that was originally designed to investigate breast cancer, restricting our evaluation to women. Although this design was intentional for interrogating a population subset and age range that encompasses postmenopausal women, we recognize our results may not be necessarily generalizable to males and other populations68,69.

In conclusion, we found consistent evidence that O3 exposure is associated with elevated levels of immune markers in both the pro-inflammatory/macrophage activation and B cell activation pathways, with exposures averaged from 1-month to one-year prior to blood draw conferring risk. For certain immune markers, such as IL-1β, TNFα and IL-8, however, associations varied by exposure window, suggesting potential critical periods of susceptibility. Replication in diverse populations and study designs will be essential to clarify the temporal and biological dynamics underlying these associations, and to better understand their role in mediating air pollution-related health outcomes.

Data availability

The data used in the current study are available for research use. The California Teachers Study welcomes all inquiries. Please visit https://www.calteachersstudy.org/for-researchers.

References

Ritz, B., Hoffmann, B. & Peters, A. The effects of fine dust, ozone, and nitrogen dioxide on health. Dtsch Arztebl Int 116(51–52), 881–886. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2019.0881 (2019).

Health Effects of Ozone in the General Population, https://www.epa.gov/ozone-pollution-and-your-patients-health/health-effects-ozone-general-population#respiratory (2024).

Costa, S. et al. Integrating health on air quality assessment–review report on health risks of two major European outdoor air pollutants: PM and NO(2). J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 17, 307–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/10937404.2014.946164 (2014).

Nitrogen Dioxide, https://www.lung.org/clean-air/outdoors/what-makes-air-unhealthy/nitrogen-dioxide#:~:text=Nitrogen%20dioxide%20forms%20when%20fossil,chemical%20reactions%20that%20make%20ozone. (2023).

What is Ozone?, https://www.epa.gov/ozone-pollution-and-your-patients-health/what-ozone (2024).

Particulate Matter (PM10) Trends, https://www.epa.gov/air-trends/particulate-matter-pm10-trends (2025).

Particulate Matter (PM2.5) Trends, https://www.epa.gov/air-trends/particulate-matter-pm25-trends (2024).

IARC: Outdoor air pollution a leading environmental cause of cancer deaths, https://www.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/pr221_E.pdf (2013).

Ostro, B. et al. Associations of mortality with long-term exposures to fine and ultrafine particles, species and sources: Results from the California Teachers Study Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408565 (2015).

Danesh Yazdi, M., Wang, Y., Di, Q., Zanobetti, A. & Schwartz, J. Long-term exposure to PM(2.5) and ozone and hospital admissions of Medicare participants in the Southeast USA. Environ. Int. 130, 104879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.073 (2019).

Duan, C. et al. Residential exposure to PM(2.5) and ozone and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis among women transitioning through menopause: The study of women’s health across the nation. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 28, 802–811. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7182 (2019).

Duan, C. et al. Five-year exposure to PM(2.5) and ozone and subclinical atherosclerosis in late midlife women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 222, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.09.001 (2019).

Ghosh, M., Rodriguez-Garcia, M. & Wira, C. R. The immune system in menopause: Pros and cons of hormone therapy. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 142, 171–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.09.003 (2014).

Wu, W., Jin, Y. & Carlsten, C. Inflammatory health effects of indoor and outdoor particulate matter. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.981 (2018).

Gruzieva, O. et al. Exposure to traffic-related air pollution and serum inflammatory cytokines in children. Environ. Health Perspect. 125, 067007. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP460 (2017).

Tsai, D. H. et al. Effects of particulate matter on inflammatory markers in the general adult population. Part Fibre Toxicol. 9, 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-8977-9-24 (2012).

Tsai, D. H. et al. Effects of short- and long-term exposures to particulate matter on inflammatory marker levels in the general population. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 26, 19697–19704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-05194-y (2019).

Tripathy, S. et al. Long-term ambient air pollution exposures and circulating and stimulated inflammatory mediators in a cohort of midlife adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 129, 57007. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP7089 (2021).

Calderon-Garciduenas, L. et al. Brain immune interactions and air pollution: macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF), prion cellular protein (PrP(C)), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) in cerebrospinal fluid and MIF in serum differentiate urban children exposed to severe vs. low air pollution. Front. Neurosci. 7, 183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00183 (2013).

Friedman, C. et al. Exposure to ambient air pollution during pregnancy and inflammatory biomarkers in maternal and umbilical cord blood: The Healthy Start study. Environ. Res. 197, 111165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111165 (2021).

Fandino-Del-Rio, M. et al. Household air pollution and blood markers of inflammation: A cross-sectional analysis. Indoor Air 31, 1509–1521. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12814 (2021).

Hajat, A. et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and markers of inflammation, coagulation, and endothelial activation: A repeat-measures analysis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Epidemiology 26, 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000267 (2015).

Chuang, K. J., Yan, Y. H., Chiu, S. Y. & Cheng, T. J. Long-term air pollution exposure and risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among the elderly in Taiwan. Occup. Environ. Med. 68, 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2009.052704 (2011).

Kelly, F. J. & Fussell, J. C. Toxicity of airborne particles-established evidence, knowledge gaps and emerging areas of importance. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 378, 20190322. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2019.0322 (2020).

Suhaimi, N. F. & Jalaludin, J. Biomarker as a research tool in linking exposure to air particles and respiratory health. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 962853. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/962853 (2015).

Tang, H. et al. The short- and long-term associations of particulate matter with inflammation and blood coagulation markers: A meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 267, 115630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115630 (2020).

Stapelberg, N. J. C. et al. Environmental stressors and the PINE network: Can physical environmental stressors drive long-term physical and mental health risks?. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013226 (2022).

Hart, J. E., Puett, R. C., Rexrode, K. M., Albert, C. M. & Laden, F. Effect modification of long-term air pollution exposures and the risk of incident cardiovascular disease in US women. J. Am. Heart Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.002301 (2015).

Bernstein, L. et al. High breast cancer incidence rates among California teachers: Results from the California Teachers Study (United States). Cancer Causes Control 13, 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1019552126105 (2002).

California Teachers Study, https://www.calteachersstudy.org/cts-data (2025).

Butterfield, L. H., Potter, D. M. & Kirkwood, J. M. Multiplex serum biomarker assessments: Technical and biostatistical issues. J. Transl. Med. 9, 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-9-173 (2011).

Breen, E. C. et al. Multisite comparison of high-sensitivity multiplex cytokine assays. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18, 1229–1242. https://doi.org/10.1128/CVI.05032-11 (2011).

Ostro, B. et al. Long-term exposure to constituents of fine particulate air pollution and mortality: Results from the California Teachers Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 363–369. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.0901181 (2010).

Venecek, M. A. et al. Analysis of SAPRC16 chemical mechanism for ambient simulations. Atmosph. Environ. 192, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.08.039 (2018).

Carter, W. P. L. & Heo, G. Development of revised SAPRC aromatics mechanisms. Atmosph. Environ. 77, 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.05.021 (2013).

Emery, C. et al. Recommendations on statistics and benchmarks to assess photochemical model performance. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 67, 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/10962247.2016.1265027 (2017).

Hu, J. et al. Predicting primary PM2.5 and PM0.1 trace composition for epidemiological studies in California. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 4971–4979. https://doi.org/10.1021/es404809j (2014).

Lipsett, M. J. et al. Long-term exposure to air pollution and cardiorespiratory disease in the California teachers study cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 828–835. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201012-2082OC (2011).

Cauble, E. L. et al. Associations between per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) exposure and immune responses among women in the California Teachers study: A cross-sectional evaluation. Cytokine 184, 156753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2024.156753 (2024).

Lacey, J. V. Jr. et al. Insights from adopting a data commons approach for large-scale observational cohort studies: The California teachers study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 29, 777–786. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0842 (2020).

Fry, R. C. et al. Individuals with increased inflammatory response to ozone demonstrate muted signaling of immune cell trafficking pathways. Respir. Res. 13, 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-13-89 (2012).

Alexis, N. E. et al. Low-level ozone exposure induces airways inflammation and modifies cell surface phenotypes in healthy humans. Inhal. Toxicol. 22, 593–600. https://doi.org/10.3109/08958371003596587 (2010).

Xu, H. et al. Low-level ambient ozone exposure associated with neutrophil extracellular traps and pro-atherothrombotic biomarkers in healthy adults. Atherosclerosis 395, 117509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.117509 (2024).

Kafoury, R. M. & Kelley, J. Ozone enhances diesel exhaust particles (DEP)-induced interleukin-8 (IL-8) gene expression in human airway epithelial cells through activation of nuclear factors- kappaB (NF-kappaB) and IL-6 (NF-IL6). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph2005030004 (2005).

Mirowsky, J. E., Dailey, L. A. & Devlin, R. B. Differential expression of pro-inflammatory and oxidative stress mediators induced by nitrogen dioxide and ozone in primary human bronchial epithelial cells. Inhal. Toxicol. 28, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/08958378.2016.1185199 (2016).

Hatch, G. E. et al. Progress in assessing air pollutant risks from in vitro exposures: matching ozone dose and effect in human airway cells. Toxicol. Sci. 141, 198–205 (2014).

Bromberg, P. A. Mechanisms of the acute effects of inhaled ozone in humans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860, 2771–2781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.07.015 (2016).

Li, W. et al. Short-term exposure to ambient air pollution and biomarkers of systemic inflammation: The framingham heart study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37, 1793–1800. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309799 (2017).

Lopez-Castejon, G. & Brough, D. Understanding the mechanism of IL-1β secretion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 22, 189–195 (2011).

David, J. M., Dominguez, C., Hamilton, D. H. & Palena, C. The IL-8/IL-8R axis: A double agent in tumor immune resistance. Vaccines 4, 22 (2016).

Sheng, Y., Li, F. & Qin, Z. TNF receptor 2 makes tumor necrosis factor a friend of tumors. Front Immunol https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01170 (2018).

Silver, J. S. & Hunter, C. A. gp130 at the nexus of inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. J. Leukocyte Biol. 88, 1145–1156. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.0410217 (2010).

Ibrahem, H. M. B cell dysregulation in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: A review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 55, 139–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdsr.2019.09.006 (2019).

Grimsholm, O. CD27 on human memory B cells-more than just a surface marker. Clin Exp. Immunol. 213, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1093/cei/uxac114 (2023).

Nascimento, M. et al. B-cell activating factor secreted by neutrophils is a critical player in lung inflammation to cigarette smoke exposure. Front Immunol 11, 1622. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01622 (2020).

Wagner, J. G., Van Dyken, S. J., Wierenga, J. R., Hotchkiss, J. A. & Harkema, J. R. Ozone exposure enhances endotoxin-induced mucous cell metaplasia in rat pulmonary airways. Toxicol. Sci. 74, 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfg120 (2003).

Mumby, S., Chung, K. F. & Adcock, I. M. Transcriptional effects of ozone and impact on airway inflammation. Front. Immunol. 10, 1610. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01610 (2019).

Ovrevik, J., Refsnes, M., Lag, M., Holme, J. A. & Schwarze, P. E. Activation of proinflammatory responses in cells of the airway mucosa by particulate matter: Oxidant- and non-oxidant-mediated triggering mechanisms. Biomolecules 5, 1399–1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom5031399 (2015).

Kurai, J., Onuma, K., Sano, H., Okada, F. & Watanabe, M. Ozone augments interleukin-8 production induced by ambient particulate matter. Genes Environ 40, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41021-018-0102-7 (2018).

Nemmar, A., Holme, J. A., Rosas, I., Schwarze, P. E. & Alfaro-Moreno, E. Recent advances in particulate matter and nanoparticle toxicology: A review of the in vivo and in vitro studies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 279371. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/279371 (2013).

Brook, Rd. et al. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation 109(21), 2655–2671 (2004).

Ridker, P. M. et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl. J. Med. 377, 1119–1131. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 (2017).

Channell, M. M., Paffett, M. L., Devlin, R. B., Madden, M. C. & Campen, M. J. Circulating factors induce coronary endothelial cell activation following exposure to inhaled diesel exhaust and nitrogen dioxide in humans: Evidence from a novel translational in vitro model. Toxicol. Sci. 127, 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfs084 (2012).

Integrated Science Assessment (ISA) for Particulate Matter, https://www.epa.gov/isa/integrated-science-assessment-isa-particulate-matter (2019).

Ural, B. B. & Farber, D. L. Effect of air pollution on the human immune system. Nat. Med. 28, 2482–2483. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02093-7 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. Fine particulate matter manipulates immune response to exacerbate microbial pathogenesis in the respiratory tract. Eur. Respir. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0259-2023 (2024).

Chen, C., Arjomandi, M., Balmes, J., Tager, I. & Holland, N. Effects of chronic and acute ozone exposure on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant capacity in healthy young adults. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 1732–1737. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.10294 (2007).

Ostro, B. et al. Chronic PM2.5 exposure and inflammation: determining sensitive subgroups in mid-life women. Environ. Res. 132, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.042 (2014).

Delfino, R. J. et al. Associations of primary and secondary organic aerosols with airway and systemic inflammation in an elderly panel cohort. Epidemiology 21, 892–902. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f20e6c (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the women of the California Teachers Study who have contributed their invaluable time and information. We would like to thank the California Teachers Study Steering Committee for the formation and maintenance of the Study within which this research was conducted. A full list of California Teachers Study team members is available at https://www.calteachersstudy.org/team.

Funding

The California Teachers Study and the research reported in this publication were supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the award numbers R01-ES033413; U01-CA199277; P30-CA033572; P30- CA023100; UM1-CA164917; and R01-CA077398. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences, the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ME, MK, MF, SW, and OM designed the study. ES, EC, MK, YZ, TB, and LM prepared data for analyses and contributed to methodology. EC performed data analyses. EC, ME, and SW drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the editing and review of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cauble, E.L., Kleeman, M.J., Zhao, Y. et al. Cross-sectional evaluation of exposure to ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and particulate mass levels on circulating immune markers in women in the California Teachers Study. Sci Rep 16, 1248 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30900-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30900-x