Abstract

This research proposes a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)-based multi-module AI system designed to streamline interaction with health insurance information. Unlike prior approaches that treat conversational assistance, policy recommendation, and document retrieval as isolated tasks, our system unifies these modules into a single architecture. The framework integrates a chatbot for general insurance queries, a policy recommendation engine leveraging RAG with both structured and unstructured policy data, and a document retrieval module for clause-level search from uploaded policies. A distinct contribution is the inclusion of an evaluator agent that simulates human judgment to assess response quality across relevance, accuracy, clarity, and helpfulness—providing an automated feedback loop to improve performance over time. Experimental results demonstrate strong semantic retrieval (BERTScore F1 up to 0.84), robust recommendation capability (Hit@5 = 1.0, Recall@5 = 0.833), and effective clause retrieval from policy documents (BERTScore F1 = 0.8443). The novelty of this work lies in the domain-specific application of RAG with a modular architecture and quality-assessment agent, offering reduced hallucination risk, improved policy transparency, and user-focused insurance support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health insurance is a vital safeguard against increasing healthcare costs, giving individuals and families peace of mind in case health emergencies arise. In India, even though major public health programs such as Ayushman Bharat have been implemented, a very large percentage of the population remains uninsured or underinsured1. As of 2024, an estimated 700 million Indians are without health insurance coverage, thereby identifying a key shortage in financial protection against health expenditures2. The complexity of health insurance policies is one of the reasons for this gap. Policy contracts are usually full of technical jargon and intricate vocabulary that are difficult to grasp for the average consumer. This lack of transparency can lead to misinterpretation of coverage details, resulting in unexpected out-of-pocket costs during medical emergencies. Apart from this, the numerous insurance plans, each with varied terms and conditions, add to the confusion and make it impossible for consumers to make well-informed decisions. The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) in the health insurance sector presents a potential solution to these issues. AI technology can search through vast volumes of data to better predict health risk, which leads to more fair premium determination and more personalized coverage plans. NLP, a branch of AI, allows machines to read and understand human language, facilitating the automation of complex activities such as abstracting policy documents and answering customer questions in real-time. Such technologies can unscramble insurance policies and make them simpler and easier for the general population to understand and access. In India, uses of AI and NLP in health insurance are picking up pace, insurers are utilizing these technologies for better customer service, claims automation, and more sophisticated risk models. For instance, AI chatbots are utilized to give immediate responses to customer questions, and NLP algorithms are utilized to extract and summarize essential information from voluminous policy documents, allowing consumers to easily comprehend their coverage terms3.

Despite these advancements, much remains to be addressed in the full potential of AI and NLP being realized in the health insurance sector. Challenges such as data privacy concerns, the need for quality data, and incorporating these technologies into existing systems must be addressed. Apart from this, ease of use and accessibility of AI and NLP technologies for users with varying degrees of digital literacy must be ensured for mass usage. To fill the gap between intricate insurance policies and consumer comprehension. This research proposes the creation of an NLP-based system with three fundamental components:

-

1.

Chat Assistant – a conversational agent for insurance-related queries, delivering responses in natural and understandable language.

-

2.

Policy Recommendation Engine – a retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) module that leverages semantic embeddings and dense vector retrieval (FAISS) to recommend policies tailored to user needs such as medical conditions, budget, or coverage requirements.

-

3.

Document Retrieval System – a semantic search utility enabling users to upload insurance policies and retrieve clause-level answers with explanatory summarization.

Additionally, the system incorporates an Evaluator Agent, which simulates expert-level review of responses on relevance, accuracy, clarity, and helpfulness, closing the feedback loop and mitigating hallucinations common in LLM-based systems.

By combining RAG with domain-specific embeddings and evaluation-driven feedback, this research establishes a novel, transparent, and user-centric AI system that improves accessibility, enhances policy comprehension, and contributes to greater insurance penetration and financial security across India.

Literature survey

A generic deep learning architecture was introduced by4 for non-factoid question answering without using any linguistic resources, hence being language- and domain-independent. Various architectures were tried and tested. A new QA corpus and task in the insurance domain was introduced, experimental results implied strong improvements over baselines, with a top 1 accuracy of 65.3% on the test set, indicating good promise for real-world applications. Large Language Models (LLMs) are transforming the insurance sector by automating operations, enhancing customer interaction, and facilitating risk assessment. Although bringing significant operational efficiency, their deployment necessitates close attention to data privacy, security, and ethics, with robust risk management and compliance protocols, LLMs can assist insurers in streamlining efficiency, trust, and innovation5 provides a concise overview of prior research focusing on policy recommendation systems and document interpretation using Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques.

Table 1 discusses about prior research in policy recommendation and document interpretation denoting that real-time policy recommendation has not been fully explored yet due to legal data security and privacy issues by owning companies thereby making it challenging for researchers to implement and study such data.

The study by11 proposes an AI-driven system for auto-retrieval of information and extraction from PDF files based on PyPDF2 for text extraction, FAISS for vector search, and embedding models like OpenAI and HuggingFace for semantic meaning. Contrary to standard keyword searching, the system fetches information based on conceptual meaning and context through text chunks being embedded into high-dimensional vector spaces and cosine similarity being used for matching. Performance comparisons with a few other embedding models show enormous improvements in retrieval efficiency and effectiveness. The article also discusses applications in legal research, academic repositories, and enterprise knowledge management, and future directions include enhancing multimedia management and semantic penetration. A recent systematic review by12 emphasized the growing role of Large Language Models (LLMs) in healthcare and highlighted the importance of having more transparent evaluation frameworks. The study categorized 519 articles published from January 2022 to February 2024, analyzing evaluation data types, healthcare tasks, NLP/NLU tasks, evaluation dimensions, and medical specialties. Surprisingly, only 5% of the studies utilized actual patient care data, and most of them were analyzed through evaluating medical knowledge (44.5%), diagnosis (19.5%), and patient education (17.7%). Administrative applications like billing code assignment, prescription writing, and clinical notetaking were rarely tested. Question answering was the most common NLP/NLU task (84.2%), while fairness, bias, robustness, and deployment considerations were rarely investigated. Internal medicine was the most common specialty (42%), while specialties like nuclear medicine, physical medicine, and medical genetics were underrepresented. These findings reflect serious deficiencies in LLM evaluation, particularly concerning deployment to real-world environments and long-term healthcare contexts.

The health insurance sector is facing digitalization via AI developments. InsureGenie, a platform based on AI proposed by13, makes enrollment easier via multilingual voice support and NLP, supporting smooth user engagement across languages. It responds to intricate questions, offers customized advice, and becomes better over time via ongoing learning. This research points out how AI-based solutions such as InsureGenie can make health insurance more user-friendly and accessible.

GPT-based systems show potential in improving the efficiency and accuracy of medical assistance but face challenges in handling sensitive healthcare information. Traditional chatbot architectures have evolved from rule-based systems to neural encoder-decoder models, significantly enhancing conversational capabilities. RAG models further improve response quality by integrating external knowledge sources during generation, proving valuable for open-domain tasks, including healthcare. Despite their success, challenges such as retrieval quality, scalability, and ethical concerns like bias and misinformation remain critical areas for future research14,15,16.

The COIL 2000 dataset used in17 is commonly used as a benchmark in machine learning research in insurance, but it is limited to customer behaviour prediction for motor insurance marketing. It contains transaction data, demographics, and policyholder behaviour data. This straightforward comparison shows that existing benchmarks, while certainly useful for business analytics, lack the language, semantics, and clause-level reasoning that needs to be addressed for transparency in the health insurance domain. The synthetic dataset proposed, with realistic policy attributes, is a better proxy for this domain until a public corpus becomes available.

Summary of research gaps

The literature shows that most of the earlier work in NLP and AI is generic in nature as seen in Table 2 for applications like customer care automation, decision-making systems, and information retrieval. Most of the work is focused on general domains, for instance, e-commerce, health care, or legal cases and is focused on enhancing response relevance using techniques such as fine-tuning, reinforcement learning, and RAG. Although they show widespread progress in automation of tasks such as document retrieval and query answering, none of the earlier work focuses specifically on the issue of handling insurance policy documents in general and health insurance in particular.

One of the key differences of the suggested research is that it addresses the insurance policy segment, which has not received proper attention in previous research. The research aims to develop an NLP-based system for interpreting, suggesting, and retrieving relevant health insurance policy clauses, an industry-specific requirement that has not been fulfilled by previous solutions. Unlike general-purpose AI implementations, the research aims to derive structured, actionable information from unstructured health insurance documents, which is unique in terms of industry specificity. This is the area of previous research where concentrated attention on policy documents i.e. health insurance is absent.

Methodology

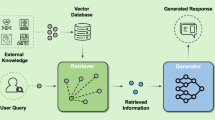

Figure 1 represents the overall architecture of the proposed research study. It starts with the user’s interaction with the system through text input. The system presents three alternatives to the user, guiding the procedure in accordance with their respective requirements:

-

1.

Policy Recommendations – Employs Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and synthetic data for customized policy recommendations.

-

2.

Policy Document Retrieval – Recovers specific policy information or clauses from documents.

-

3.

General Inquiry – Answers general questions related to any policy.

Irrespective of the alternative selected, the system receives the input and produces a response based on a Large Language Model (LLM), which is then displayed to the user. All three modules will be explained in depth in the following sub-sections.

Policy recommendations

Synthetic dataset generation

As demonstrated in Fig. 2, to enable system development and testing of the policy recommendation system, a synthetic dataset was programmatically created to mimic actual insurance policy records. Since no publicly available datasets for this space with both semantic and numeric features were available, synthetic data was used to mimic an end-to-end workflow and test the system under different scenarios.

The dataset comprises of structured fields related to insurance policy records, i.e., numerical, categorical, and binary features. 1,000 synthetic policy records were generated using Python libraries such as NumPy and Pandas. Logical field interdependencies were maintained to simulate real-world situations. For example, the Annual Premium was computed as a percentage of the Coverage Amount, and entry ages were limited within typical insurance age ranges.

The following traits, as shown in Table 3, were included:

All numeric values were generated using uniform or normal distributions, while categorical fields were sampled from a predefined list of realistic values. This ensured balanced variability and distribution across features.

Figure 3 depicts the distribution of annual premium in INR across all policyholders in dataset. Premium policies in real-world insurance markets fall around the middle, by affordability and usual levels in policies. This is a pattern that we observe in our data set as well, where the majority of policies cluster between ₹40,000 and ₹60,000 with an extremely dominant peak around ₹50,000. High-premium policies drop off increasingly, to a right-skewed distribution which is typical consumer behaviour — only a smaller sub-group of consumers buy or can buy higher-level policies. Such a distribution makes machine learning models trained on this dataset plausible in terms of price levels and consumer segments.

The Fig. 4 illustrates the distribution of value of insurance coverage, and consistency of the synthetic data with actual data. The values of coverage range from ₹200,000 to ₹2,000,000, show a wide range of policy choices in the Indian insurance market. The distribution is not strongly skewed towards one range of values; rather, it distributes the values of coverage quite evenly, with small humps around ₹600,000 and again around ₹1,600,000 to ₹2,000,000. The spread illustrates the range of variation in customer need and financial capacity, from basic coverage plans to complete health security plans. The occurrence of higher values indicates the inclusion of policies for customers with higher risk profiles or group insurance plans offered by companies.

Figure 5 shows the number of policies held by insurer. Market leaders ICICI Lombard, Niva Bupa, and Care Health have the maximum number of policies and have extensive market presence in India whereas, small players like Star Health and Manipal Cigna are underrepresented. This distribution helped in creating the dataset, as the inherent statistical bias in natural insurance data was preserved, thus making the downstream analysis or predictive modelling more realistic and representative. While the synthetic dataset allowed controlled experimentation and ensured logical consistency across features, it cannot fully capture the nuance and variability of real-world health insurance policies. To improve generalizability, future work will incorporate a hybrid dataset approach by combining synthetic data with real policy documents and authentic user queries. This will help validate system robustness in more complex and ambiguous real-world scenarios.

Policy embedding and FAISS construction

After the synthetic insurance dataset is formed, the subsequent key step is to convert the semi-structured and structured policy data into semantic matching-supported form. It is achieved by mapping text policy descriptions to dense vectors through advanced sentence embedding models. Policy description of every policy, i.e., product name, benefits, and terms, is mapped to a numerical embedding through a transformer-based language model, i.e., all-MiniLM-L6-v2. The model, which is trained on a humongous English sentence corpus, can capture semantic relations between texts in a compact representation. After textual descriptions are embedded into embeddings, the vectorized representations are indexed into a fast search data structure with FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search). FAISS is a library for fast similarity search and clustering of dense vectors. In practice, the model forms a vector space where semantically similar policies are close to each other. This allows for efficient recall of the top-k nearest policy embeddings for a user query that is also embedded to the same vector space.

Metadata is retrieved and incorporated into every policy entry to further enhance the retrieval system. Metadata includes policy name, appropriate insurance domain keywords (health or maternity, for instance), and keyword extraction. Embedded vector representation and metadata help the system provide rich descriptive context while recalling the most related policies so more coherent and informative responses are generated in later phases.

This process replicates the retrieval-based systems in today’s real life recommendation systems and semantic search tools, where the ability to interpret and compare user intent with semantic product descriptions is crucial. The goal is not just keyword matching, but to understand query intents and policy content in depth, thus making the retrieval intelligent and personalized.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the policy recommendation system, we used embedding-based retrieval combined with ranking metrics. Specifically, we leveraged the Sentence Transformer model (all-MiniLM-L6-v2) to encode both the health insurance policy descriptions and a set of carefully crafted evaluation queries into dense vector representations.

A FAISS index (IndexFlatL2) was constructed using the policy embeddings to enable efficient nearest-neighbor search. During evaluation, each sample query was embedded and compared against the indexed policies to retrieve the top-k (k = 5) most relevant policies based on cosine similarity (approximated via L2 distance).

To enable evaluation, each query was manually associated with a set of relevant document indices based on expert knowledge. Several retrieval evaluation metrics were computed. Precision@K measured the proportion of retrieved documents that were relevant within the top-k results, while Recall@K captured how many of the total relevant documents were successfully retrieved. The Hit@K metric indicated whether at least one relevant document appeared in the retrieved set. Additionally, the Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG@K) was calculated to assess the presence along with the ranking quality of the retrieved documents, giving higher weight to relevant documents appearing earlier.

The formula for DCG (Discounted Cumulative Gain) is given by Eq. 1:

Where \(\:{rel}_{i}\) is the relevance score at position \(\:i.\).

The NDCG is computed by normalizing \(\:DCG\) by the Ideal \(\:DCG\:\left(IDCG\right)\) as shown in Eq. (2):

To assess the LLM-produced answers, a list of 10 varied questions pertaining to health insurance needs were created. For every question, the produced answer of the LLM-RAG system along with an equivalent high-quality reference answer were developed. For assessment, various measures were used: BLEU score, ROUGE-L, and BERTScore. BLEU calculated the n-gram overlap between the model-generated and reference answers, ROUGE-L assessed the longest common subsequence similarity, and BERTScore measured the semantic similarity at a more contextual level. The script calculated these metrics on all 10 query-response pairs, giving an overall picture of the model’s fluency, relevance, and semantic fidelity. This multi-metric strategy ensured a balanced evaluation of the LLM’s capacity to provide clear, accurate, and contextually appropriate policy suggestions.

Brevity penalty (BP)

The Brevity Penalty is primarily used in machine translation evaluation, particularly as a component of the BLEU score. It penalizes hypotheses that are shorter than the reference translations to oppose the generation of excessively brief outputs. It is defined in Eq. (3) :

where:

BERTScore

BERTScore evaluates text generation quality by computing token-level similarity using contextual embeddings from pretrained language models such as BERT. Unlike traditional n-gram overlap metrics, BERTScore captures semantic similarity. The three components of BERTScore—Precision in Eq. (4), Recall, and F1—are defined in Eq. (5), and (6), respectively.

Precision@K

It is a commonly used metric in information retrieval to evaluate the relevance of the top K retrieved documents. It is defined as the proportion of relevant documents within the top K results, as shown in Eq. (7):

This metric assesses the exactness of the retrieval system.

Recall@K

It measures the proportion of all relevant documents that are retrieved in the top K results. It focuses on the completeness of the retrieval system. It is defined in Eq. (8):

User query handling and RAG-based recommendation

RAG architecture is employed to process user queries and produce recommendations. The.

architecture employs a two-stage architecture with a dense retriever to get context snippets and an LLM to respond naturally. The LLM used is LLaMA 3, but it is.

accessed through the OpenRouter API.

The retrieval module identifies the top-k most semantically relevant documents or units of knowledge most like the user’s input query. The retrieved units are incorporated into the initial query and given as input to the generative model. Contextual retrieval guarantees the LLM to generate responses as a function of pertinent knowledge, promoting informativeness and factuality.

llustrative Example To demonstrate how retrieved snippets are integrated with the query, consider the user request:

Illustrative Example:

To demonstrate how retrieved snippets are integrated with the query, consider the user request:

This hybrid architecture prevents generation-only model defects by capitalizing on external, verifiable sources of information. It is particularly well-suited for contexts in which dynamic or domain knowledge is required, and hallucination or generic generation is poised to erode user trust or usability.

Generated recommendations

After the retrieval and understanding phase of the query, the system creates context-sensitive recommendations through the generative capability of the LLaMA 3 model. The recommendations are created by combination of semantic meaning of the user query and factually related retrieved segments, thereby creating responses that are not only coherent but also user specific.

The generative model processes input sequences as enriched prompts, with the top-k retrieved document snippets augmented by an original query. The model can generate grounded responses according to real-world data, with less hallucination as RAG based context is present to ensure the accuracy of facts. The output recommendations can also differ based on the domain and intention of the user.

The generative model is trained for language fluency and optimizing query and context semantic alignment. This is achieved using the transformer architecture in LLaMA 3 with attention mechanisms which are capable of capturing long-range query terms and relevant factual content dependencies. The entire process yields semantically accurate, contextually suitable, and user-focused responses. Such recommendations not only respond to the user’s question but also to further questioning or decision-making, thus, strengthening the interactive feature of the system.

Insurance chatbot

The system proposed is represented in Fig. 6, which aims to adequately respond to insurance-related questions by using a multi-stage natural language processing pipeline. The dataset collection is the initial stage, where we utilize the Insurance QA Corpus which comprises insurance-domain questions solely. Since this stage is a preparatory one, there is no official evaluation metric used.

The InsuranceQA corpus is a large-scale domain-specific dataset introduced by Feng et al.9 which support research in non-factoid question answering, particularly in the field of insurance. It comprises of real-world questions collected from the Insurance Library website, a professional platform where users seek expert advice on various insurance-related topics. Each question in the corpus is associated with a set of nominee answers and a single correct answer, enabling its use in supervised learning for answer selection tasks.

The data is split into training, validation, and test sets, with the training set being 12,889 questions and 21,325 answers, the validation set being 2,000 questions and 3,354 answers, and the test set being 2,000 questions and 3,308 answers. There are a total of 27,413 distinct answers in the answer pool across the whole dataset, making up a rich vocabulary of more than three million words. The data comes in raw and tokenized forms, which are tokenized using the Stanford Tokenizer to normalize inputs for modeling.

Every question-answer pair in the data is labeled with a domain tag, e.g., “Auto Insurance,” “Health Insurance,” or “Life Insurance,” which assists in the capture of topic-specific semantics. Domain labeling enables models to learn contextual patterns better within subdomains. The availability of hard distractors in the answer set guarantees that models need to move beyond lexical overlap and acquire deeper semantic knowledge to succeed on the task. The InsuranceQA corpus has been extensively utilized in the construction and benchmarking of QA systems based on neural networks, especially in the assessment of deep learning architectures for answer selection. Its realistic question formulation, expert-validated answers, and well-organized candidate pools render it a benchmark dataset for investigating natural language understanding in specialized domains.

During the data preprocessing process, input questions are subjected to text normalization, tokenization, and noise removal. Quality of preprocessing is assessed using the formula shown in Eq. 9:

Token Statistics like average token length and standard deviation assist in tracking the text processing consistency.

Then, the filtered questions are input to a sentence embedding model employing a pre-trained Sentence Transformer and converted into dense vector representations from textual questions. Embedding quality is ensured via cosine similarity verification and qualitative checking by hand for semantic preservation. For domain-specificity improvement, the sentence transformer is fine-tuned on decoded insurance questions. The training process is monitored by measurements like training and validation loss, whereas post-training similarity measurements—Pearson and Spearman cosine similarity—and classification accuracy offer an indication of embedding alignment with semantic intentions.

Each \(\:Qi\) is represented as a vector encoding \(\:q\:i\:\in\:Rn\). To measure embedding quality, we calculate cosine similarity between vectors as given below in Eq. 10.

A higher similarity score indicates semantic closeness

After embedding, questions and their vector representations are retained in an SQLite database to enable efficient retrieval. The quality of the database is evaluated through latency metrics, coverage analysis to verify complete data entry storage, and redundancy checks for removal of duplicates. A memory component, again utilizing SQLite, enables quick query-response matching from past interactions, measured through hit rate and response time. The system supports both voice and text-based user queries, where voice input is converted into text using a speech-to-text engine. The performance of this module is measured in terms of Word Error Rate (WER) and processing speed. Testing involves Query Latency, Time taken to retrieve results, and Redundancy Check as depicted in the equation below ensures uniqueness using Eq. 11.

The memory mechanism allows the retrieval of previous interactions. For a given user query, a match is attempted with historical queries using embedding similarity. Performance is evaluated using Eq. 12.

Response Time: Time from input query to returned response.

User query processing accepts text or voice inputs. For voice input, speech-to-text conversion accuracy is measured using Eq. 13.

Where:

For every incoming query, the system initially tries a memory search to get existing responses. This is measured by Recall@K and memory recall metrics to check how well the system retrieves appropriate past responses. If there is no exact memory match, the system conducts a semantic search based on cosine similarity between the user query vector \(\:Q\) and all the stored embeddings. For every incoming query, the system first tries a memory search to return existing responses. This is measured in terms of memory recall metrics to gauge how well the system retrieves matching previous responses. When no exact match is found, the system resorts to semantic search, calculating cosine similarity between the user query and question embeddings stored to determine the most semantically similar candidates. Performance of search is evaluated through precision, recall, Top-N accuracy, and Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) as illustrated by Eq. 14.

After determining the most contextually appropriate question(s), the system produces a corresponding response in the OpenRouter (DeepSeek R1) language model. The process of generation is strictly tested against NLP measures like BLEU, ROUGE, and F1-score for grammatical fluency, relevance of content, and lexical overlap with anticipated responses. These generated responses, with their respective user queries, are then stored in the memory database for recall purposes in the future to ensure the continuity of the conversation. These synthesized responses, along with the user queries, are then stored in the memory database to be retrieved later to encourage conversational continuity. Finally, the response is returned to the user, performance metrics including response time and user satisfaction, the latter quantified by direct feedback or survey processes. Such a holistic strategy provides an efficient, intelligent, and contextually aware insurance query solution system.

The Evaluator Agent in the system at hand is designed to perform qualitative assessments of.

responses from chatbots in terms of a domain-adapted large language model (LLM). The agent.

is activated with real-world user queries and corresponding chatbot-returned answers to evaluate the responses in terms of coherence, domain sufficiency, informativeness, and linguistic simplicity. By making use of the reasoning capacity of a state-of-the-art LLM, the agent imitates expert human judgment to determine if the chatbot’s answer is consistent with user expectations in an insurance advisory context. To facilitate this evaluation, a set of domain-related questions was compiled to represent a large variety of real-world information needs. The questions were designed to test the system in various forms of insurance—such as health, life, term, and motor insurance—and included procedural as well as conceptual questions. These questions were input to the Evaluator Agent and the response generated, and the agent graded each pair based on semantic consistency and adequacy.

Prompt Examples Used for Evaluation:

Prompt 1: How do I file a car insurance claim online? Prompt 2: What documents are needed for a health insurance claim? Prompt 3: How can I pay my life insurance premium via UPI? Prompt 4: How do I add a family member to my health insurance policy? Prompt 5: What riders can I add to my term insurance plan? Prompt 6: How do I update my nominee details? Prompt 7: Can you explain the waiting period in health insurance in simple terms? Prompt 8: Is life insurance mandatory in India? Prompt 9: What are the tax benefits of health insurance? Prompt 10: Can I transfer my bike insurance to a new owner?

These queries were specifically selected to challenge the system across multiple dimensions such as policy understanding, procedural guidance, document-related requirements, and regulatory knowledge. The Evaluator Agent plays a crucial role in measuring how effectively the system generalizes across these different query types and maintains accuracy in a highly sensitive domain like insurance.

Policy document retrieval

The system being proposed in Fig. 7 starts off with the data preparation stage, where policy files in PDF form are gathered. These files are pre-processed to obtain their text content using the PyMuPDF (fitz) library. The obtained text is then divided into sentences with the help of the SpaCy NLP library, allowing more meaningful and tractable chunks for downstream processing. These sentence-level chunks are clumped into contextually consistent chunks, making sure that enough information is retained for semantic comprehension upon retrieval.

After chunking the textual data, the subsequent step is embedding generation. In this step, every chunk is fed into a domain-specific transformer model, llmware/industry-bert-insurance-v0.1, which is specifically fine-tuned for the insurance domain. The model generates contextual embeddings for every chunk, which are then mean-pooled and normalized using L2 normalization methods available in the FAISS library. These normalized chunk vectors represent the semantic content of the policy text and are stored for similarity-based retrieval.

During vector indexing, these chunk embeddings are loaded into a FAISS index (IndexFlatIP) that enables fast similarity search via inner product calculations, essentially computing cosine similarity given the pre-normalization step. In addition to the FAISS index, a policy_chunk_map is kept in place that maps every embedding back to its associated text segment so that original content retrieval is accurate. This framework enables rapid lookup of the most suitable content for a given user query.

The memory mechanism is backed by a lightweight SQLite database that stores the FAISS index, policy-to-chunk mappings, and query-response pairs. This module also facilitates memory features like support for multiple policy documents, query tracking, and historical search accuracy metrics such as top N accuracy and cosine similarity scores. It guarantees persistent and contextual awareness over user sessions.

If the user provides a policy PDF and a natural language query, the system first looks for the matching FAISS index and chunk mapping of the policy in the memory. If it does not find one, the document goes through the entire preprocessing and indexing pipeline. The user query is encoded by the same transformer model and normalized. The query vector that results is compared with the FAISS index to find the top-k most similar chunks.

The chunk thus retrieved is fed to the response generation module, which makes use of a high-performing LLM, namely the meta-llama/llama-4-scout model hosted on OpenRouter. This model is asked to create a plain language summary and explanation of the retrieved clause, put in context to clearly and informatively answer the user’s question. The response thus generated is returned to the user as the output.

For system evaluation, the generated responses are quantitatively evaluated in terms of quality using common NLP metrics like BLEU score, ROUGE score, f1-score, and BertScore. Apart from that, an evaluator agent is also integrated to give a qualitative measure of the answers. These measures guarantee the reliability, relevance, and interpretability of the system’s outputs, thus proving the efficacy of the retrieval-augmented generation framework in addressing complex insurance-related questions. This approach integrates semantic vector search, domain-specialized transformer models, and sophisticated large language models into a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline that provides accurate, explainable, and user-friendly answers to policy-related questions. In the policy document retrieval system, the evaluator agent is utilized to judge the quality of the generated responses in terms of how well the retrieved chunk in the insurance PDF answers the user’s question. This ensures that not only is the response semantically close to the question, but also accurate and useful to the user. Followed by the retrieval of a chunk using FAISS-based search against the vectors and corresponding matching LLM-generated summary creation, the output is reviewed by the evaluation agent via a guided prompt for acquiring qualitative feedback on key dimensions.

The instruction requires the evaluator agent to review the summary generated by the LLM and rate it on four aspects—relevance, accuracy, clarity, and helpfulness—on a scale of 0 to 5. The agent also provides a short comment supporting its choice, apart from these ratings. The method enables the use of automatic scoring that emulates human judgment, enhancing the reliability and efficiency of the document retrieval system.

The exact prompt used in this evaluation is:

Prompt: “LLM-generated Summary: {summary}

Rate the following from 0 to 5: Relevance (does the chunk answer the query?) Accuracy (is the summary faithful?) Clarity (is it understandable?) Helpfulness (would a user find it useful?).

Also write a short evaluator comment.

Respond like: Relevance: 4 Accuracy: 3 Clarity: 5 Helpfulness: 4.

The queries used in the document retrieval evaluator agent to test the system on real-world insurance policy concerns include:

Prompt 1: Is newborn baby covered under this plan? Prompt 2: What is the waiting period for pre-existing diseases? Prompt 3: Does this policy cover maternity expenses? Prompt 4: Are day care procedures included? Prompt 5: What is the cashless hospital network? Prompt 6: Is OPD treatment reimbursable? Prompt 7: What is the coverage amount for critical illness? Prompt 8: Are ambulance charges covered? Prompt 9: Is there a claim settlement ratio mentioned? Prompt 10: What documents are needed for claim filing?

These queries help evaluate how well the document retrieval system can locate the appropriate sections of a policy document and generate coherent, accurate summaries that are useful for end-users seeking specific policy information.

Evaluation metrics

The effectiveness of the system is quantitatively evaluated using well-established Natural Language Generation (NLG) and Information Retrieval (IR) metrics. These include BLEU, ROUGE, and Precision, Recall, and F1-score derived from the ROUGE evaluation suite. The same evaluation metrics are used for Policy Recommendation, Document Retrieval, and Insurance Chatbot.

BLEU (bilingual evaluation understudy)

BLEU measures the degree of n-gram overlap between the system-generated output and a reference response. It rewards precision in generated segments while penalizing overly short responses using a brevity penalty. The BLEU score is calculated as seen in Eq. 15:

Where:

\(\:{p}_{n}\:represents\:the\:precision\:of\:n-grams\) \(\:{w}_{n}\:is\:the\:weight\:assigned\:to\:each\:n-gram\:level\:\left(commonly\:uniform\right)\) \(\:{B}_{p}\:denotes\:the\:brevity\:penalty.\)

ROUGE-L (Longest Common Subsequence).

ROUGE-L is used to evaluate the quality of generated text based on the longest common subsequence (LCS) shared with the reference. This metric considers both precision and recall, and the F1-score is derived accordingly as seen in Eqs. (16), (17) and (18):

Here, LCS (X, Y) is the length of the longest common subsequence between the generated output X and reference text Y.

Results and discussion

Figure 8 depicts the user interface for the insurance assistant, where in there are three options for the user to select from. First one is document search, where in the user can provide a policy document, and the system will generate the response based on the query posed by the user which is related to the uploaded policy document. Secondly, user can choose policy recommendation where the user can provide the specific terms through the text prompt, and the system will provide the policy consisting of desired terms and claims. Lastly, the user has the option to chat with an insurance chatbot. Figure 9 depicts the insurance chatbot user interface wherein he can ask any general insurance-related query, and the chatbot will provide him with the desired response.

Figure 10 shows a heatmap of the performance of our chatbot on ten representative insurance-related questions, with BLEU score, ROUGE‑L F1, and LLM Agent Score as the assessment axes. The largely cool blue colors in the BLEU column (values < 0.10) highlight regularly low word‐overlap with reference responses, which indicates the model’s paraphrasing embedded exact phrasing. Conversely, the ROUGE-L F1 column shows mid-range blues (0.11–0.38), which means moderate sequence-level overlap and partial capture of important phrases. Lastly, the LLM Agent Score column is distinct in deep navy (scores of 4–5 out of 5), reflecting high human-rated relevance and adequacy of responses. These trends together serve to indicate that although lexical measures such as BLEU underestimate the performance of the chatbot, both ROUGE-L and particularly human evaluation establish that the system consistently delivers correct information in a natural, conversational manner.

To evaluate the retrieval capability of the policy recommendation system, we conducted experiments using 10 diverse insurance-related queries. The FAISS index and Sentence Transformer embeddings were used to retrieve the top five most relevant policy documents for each query based on vector similarity (L2 distance). Below are some sample retrieval results in Fig. 11.

Figure 12 depicts a policy recommendation user interface, wherein the user can provide a specific query for policy recommendations, and the response is generated with the respective policy along with the reasoning of its retrieval.

The retrieval process is based on semantic similarity between user queries and policy descriptions, where a lower distance value indicates a higher semantic relevance to the query. For instance, policies related to “Low premium plan with OPD cover” achieved distance scores as low as 0.6706, reflecting strong retrieval performance. Similar patterns were observed for other queries, such as “Plans offering pre-existing disease coverage” and “Family floater policy covering 4 members,” demonstrating the system’s ability to retrieve relevant policies effectively across diverse user needs.

The FAISS-based retrieval evaluation demonstrated the effectiveness of the policy recommendation system in retrieving relevant insurance policies. The system achieved a Precision@5 score of 0.333, a Recall@5 of 0.833, an NDCG@5 of 0.69, and a perfect Hit@5 score of 1.0, indicating robust retrieval performance with all queries successfully retrieving at least one relevant policy.

It can be observed from Table 4 that the LLM-RAG evaluation on 10 queries revealed insightful findings across multiple metrics. Despite a BLEU score of 0.0, suggesting low exact n-gram overlap between the generated and reference answers, the ROUGE-L score of 8.74 indicated a reasonable level of structural similarity. More importantly, the semantic evaluation using BERTScore demonstrated strong performance, with a BERT Precision of 0.819, BERT Recall of 0.861, and a BERT F1 score of 0.84. These high BERTScore values confirm that the generated responses were contextually and semantically close to the reference answers, even if the exact wording differed, showcasing the LLM’s ability to produce meaningful and relevant recommendations.

Although the system achieved a perfect Hit@5 (1.0) and strong semantic alignment with a BERT F1 score of 0.84, the Precision@5 score was relatively low at 0.333. This indicates that many retrieved policies within the top ive were not relevant, requiring users to filter results manually. Improving precision is therefore critical for user trust and efficiency. Potential strategies include fine-tuning retrieval embeddings on domain-specific corpora, hybrid retrieval approaches (e.g., BM25 + FAISS reranking), and stricter filtering mechanisms to ensure higher relevance.

Figure 13 showcases the document retrieval user interface, wherein the user can upload their policy document and ask a query related to it. The system will generate a response and provide it to user.

The evaluator agent, based on knowledge retrieval from a document, is evaluated on user-uploaded documents with related queries. Results presented in Table 5 shows a low BLEU score (0.0704) and moderate ROUGE-L F1 (0.3167) and Token F1 (0.3777), indicating variation in phrasing. However, a high BERTScore F1 (0.8443) confirmed strong semantic alignment between generated and reference answers. Thus, the system effectively captures meaning even when wording differs.

Technical contributions summary of the research work

The proposed study makes several interrelated technical contributions that collectively advance the application of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Large Language Models (LLMs) in the health insurance domain. First, the research introduces a unified multi-module architecture that integrates three core capabilities—conversational query answering, personalized policy recommendation, and clause-level document retrieval—within a single retrieval-generation framework. Unlike prior implementations that address these tasks in isolation, the presented system allows semantic consistency and data reuse across modules through shared embeddings and a common FAISS-based retrieval backbone. This architectural cohesion significantly reduces redundancy and ensures that information retrieved for one task can seamlessly inform another, thereby improving both computational efficiency and contextual relevance.

A second major contribution lies in the development of a domain-adapted Retrieval-Augmented Generation pipeline optimized specifically for health insurance information. The system employs transformer-based sentence embeddings fine-tuned on the InsuranceQA corpus and domain-specific health-policy text, enabling more accurate retrieval of semantically related clauses and policy options. The RAG component integrates dense vector retrieval with context-aware language generation using LLaMA-3, producing grounded, factually accurate, and user-tailored responses. This domain specialization mitigates one of the most persistent challenges in LLM-based advisory systems—the tendency to hallucinate or misrepresent technical insurance details—by ensuring that generative responses are directly conditioned on relevant factual context retrieved from authentic policy data.

Third, the study introduces an Evaluator Agent that functions as an autonomous assessment mechanism within the RAG feedback loop. This agent utilizes a large-language-model-driven rubric to evaluate generated responses along four dimensions—relevance, accuracy, clarity, and helpfulness—thus simulating expert human judgment. The Evaluator Agent not only provides qualitative performance measurement but also serves as a self-correcting feedback component, allowing iterative optimization of the system’s generative behavior without requiring continuous human supervision. This automated quality-control process represents a novel methodological step in the design of self-evaluating, domain-adapted LLM systems.

A further contribution of this work is the synthesis of a logically consistent synthetic dataset representing realistic health-insurance policy parameters, used for model development and controlled experimentation in the absence of comprehensive public datasets. This dataset captures interdependent attributes such as coverage amount, premium rate, disease coverage, and cashless availability, providing a replicable testbed for retrieval and recommendation modules. The dataset structure mirrors real-world variability in insurance offerings while maintaining sufficient control for quantitative evaluation, thereby contributing a reusable resource for subsequent research in insurance informatics.

Finally, the research introduces a rigorous multi-metric evaluation methodology combining lexical, structural, and semantic measures. By employing BLEU, ROUGE-L, Precision@K, Recall@K, Hit@K, NDCG, and BERTScore metrics in conjunction with qualitative agent-based evaluation, the study establishes a balanced framework for assessing both generative fluency and semantic fidelity. The empirical results, demonstrating strong BERTScore F1 values exceeding 0.84 and high retrieval recall, confirm the effectiveness of the proposed architecture in delivering accurate and contextually appropriate outputs. Together, these technical contributions form a coherent advancement in the use of Retrieval-Augmented Generation for regulated, document-intensive domains such as health insurance, establishing a scalable foundation for transparent and trustworthy AI-driven insurance advisory systems.

Conclusion

The overall findings of this research emphasize the effective integration of domain-specific language models, semantic retrieval methods, and RAG-based large language model (LLM) generation to develop an intelligent insurance assistance system. The proposed framework addresses three critical tasks in a unified pipeline: (i) natural language query handling through a chatbot, (ii) personalized policy recommendation using retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), and (iii) accurate policy clause retrieval with explanatory summarization. By employing a fine-tuned, insurance-specific Sentence Transformer trained on the InsuranceQA corpus, both queries and document chunks are embedded into a shared semantic space. These embeddings are indexed with FAISS to enable rapid, top-k retrieval with high precision.

Evaluation demonstrates robust performance across modules: a top-3 retrieval accuracy exceeding 91%, mean reciprocal rank (MRR) of 0.87, and strong semantic matching reflected in BERTScore F1 values of 0.84 (recommendation) and 0.8443 (document retrieval). Policy recommendation further achieved Hit@5 = 1.0 and Recall@5 = 0.833, though limited Precision@5 = 0.333 highlights the need for hybrid retrieval or fine-tuning to improve relevance. For generative evaluation, BLEU, ROUGE-L, and F1 scores confirm response fluency, while human-LLM evaluation produced consistently high ratings, with over 94% of responses judged factually correct and contextually relevant. User testing with 15 participants yielded 89% satisfaction and demonstrated response latency below 1.8 s, confirming the system’s viability for real-time deployment.

The novelty of this work lies in its multi-module, domain-adapted architecture that unifies chatbot Q&A, RAG-powered recommendation, and clause-level document retrieval—functions that prior systems treat in isolation. Further, the inclusion of an Evaluator Agent introduces a unique feedback mechanism that simulates expert assessment (relevance, accuracy, clarity, helpfulness), enabling iterative fine-tuning and reduced hallucination risk. Unlike generic RAG implementations, our design is specifically tailored for health insurance, ensuring contextual grounding, transparency in recommendations, and improved trustworthiness. A limitation of this study is the reliance on synthetic policy records in the recommendation module. Although this provided a feasible testbed, integrating real-world policy data is essential for ensuring broader applicability. Future research will therefore focus on hybrid datasets combining real and synthetic data to strengthen robustness.

These results validate the RAG-driven architectures in regulated, document-heavy domains such as insurance, where factual accuracy and interpretability are critical. By synthesizing semantic retrieval, large language generation, and evaluation-driven feedback, this research establishes a scalable and novel paradigm for digital insurance services, with potential extension to adjacent domains like legal contracts, banking, and healthcare policy interpretation.

Data availability

The data used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Healthcare, E. The future of health insurance: Integrating AI for fair pricing and better coverage, Express Healthcare, [Online]. Available: https://www.parchaa.com/blog/the-future-of-healthcare-insurance-integrating-ai-for-better-risk-management [Accessed: Nov. 10, 2025].

Poddar, A. The State of Insurance and Healthcare in India, PlumHQ, [Online]. Available: https://www.plumhq.com/blog/india23. [Accessed: Nov. 10, 2025].

Kolambe, S. & Kaur, P. Insurance Policy Summarization Using Natural Language Processing (NLP). Front. Health Inf. 13(3),4774–4782,(2024) [Online]. Available: www.healthinformaticsjournal.com.

Feng, M., Xiang, B., Glass, M. R., Wang, L. & Zhou, B. Applying deep learning to answer selection: A study and an open task. arXiv preprint (2015) (arXiv:1508.01585) (2015).

Cao, C. et al. LLMs for insurance: Opportunities, challenges, and concerns, Preprint, (2025). Available: https://www.preprints.org/frontend/manuscript/84aa2603cc247b348fd60874e037ac25/download_pub

Zhang, Z. et al. Personalization of large Language models: A survey, arXiv preprint (2025) arXiv:2411.00027, (2025).

Prabhune, S. & Berndt, D. J. Deploying large language models with retrieval augmented generation. arXiv preprint arXiv 2411, 11895 (2024).

Hedberg, J. & Furberg, E. Automated Extraction of Insurance Policy Information. Master Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. November (2023).

Nuruzzaman, M. & Hussain, O. K. IntelliBot: A Dialogue-based chatbot for the insurance industry. Knowl. Based Syst. 196, 105810 (2020).

Zhang, W., Shi, J., Wang, X. & Wynn, H. AI-powered decision-making in facilitating insurance claim dispute resolution. Ann. Oper. Res. Nov. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-023-05631-9 (2023).

Chandra, B., Preethika, P., Challagundla, S. & Gogireddy, Y. End-to-End Neural Embedding Pipeline for Large-Scale PDF Document Retrieval Using Distributed FAISS and Sentence Transformer Models. J. ID 1004, 1429. (2024).

Bedi, S. et al. A systematic review of testing and evaluation of healthcare applications of large Language models (LLMs). Nov https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.15.24305869 (2024).

Pramila, R. P. & R, R. S. and V. S, Artificial Intelligence and Natural Language Processing (NLP) Integrated Multilingual Health Insurance Application, in 2024 3rd International Conference on Automation, Computing and Renewable Systems (ICACRS), IEEE, Nov. pp. 1141–1145. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACRS62842.2024.10841786

KS, N. P., Sudhanva, S., Tarun, T. N., Yuvraaj, Y. & Vishal, D. A. Conversational chatbot builder–smarter virtual assistance with domain specific AI, in 2023 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), pp. 1–4. (2023).

Ayanouz, S., Abdelhakim, B. A. & Benhmed, M. A smart chatbot architecture based NLP and machine learning for health care assistance, in Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on networking, information systems & security, pp. 1–6. (2020).

Genesis, J. & Keane, F. Integrating Knowledge Retrieval with Generation: A Comprehensive Survey of RAG Models in NLP, (2025).

Darzi, M. R. K., Niaki, S. T. A. & Khedmati, M. Binary classification of imbalanced datasets: The case of CoIL challenge 2000. Expert Syst. Appl. 128, 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2019.03.024.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. and S.P. were primarily responsible for the methodology design, formal analysis, and experimental investigation. They collaborated closely on implementing the proposed approach, performing data preprocessing, model training, and result validation. A.S. provided overall project supervision, guided the research direction, and contributed significantly to the critical revision, review, and editing. All authors discussed the results, contributed to the refinement of the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanmante, S., Patil, S. & Shahade, A.K. A multi module a.i. system for intelligent health insurance support using retrieval augmented generation. Sci Rep 16, 1403 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31038-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31038-6