Abstract

Pharmacological treatment is commonly used for patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP). However, very low-quality evidence exists for paracetamol as a treatment option for CLBP; therefore, recommendations are contradictory among the guidelines. This randomized controlled study aimed to compare the analgesic effects of paracetamol and celecoxib in a non-inferiority trial. This non-inferiority trial tested the hypothesis that paracetamol is as effective as celecoxib for the treatment of CLBP within a pre-specified non-inferiority margin. One hundred fifty-six patients with CLBP were considered eligible and randomly allocated to a group receiving paracetamol or celecoxib. The pain intensity was measured using a numerical rating scale as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were pain-related psychological variables, quality of life, and adverse events. One hundred thirty-nine patients completed the study (paracetamol, 70; celecoxib, 69). We observed that the mean differences in the NRS changes between the two medication groups from baseline to weeks two and four did not significantly exceed the non-inferiority margin. Paracetamol had a superior effect on pain-related psychological variables and quality of life compared to celecoxib. These results suggest that paracetamol provides analgesic effects comparable to celecoxib for CLBP, meeting the criteria for non-inferiority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic nonspecific low back pain (CLBP) is a primary pain that lasts for more than three months1. The prevalence of CLBP is 19.6% in individuals aged 20–59 years2, and 36.1% in those aged \(\ge\) 60 years3. CLBP is framed in a multidimensional conceptual model to inform the assessment and management of the associations between behavioral, psychological, and social factors and future persistence of pain and disability4. The severity of chronic pain was recorded using pain intensity1, which was adopted as the primary outcome. Additionally, emotional distress5,6,7,8 and pain-related interference with functional ability9,10 are commonly assessed.

Pharmacological treatment is recommended following an inadequate response to non-pharmacological treatments4. Recent guidelines for pharmacological treatment of CLBP commonly recommend the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)4,11,12,13. The therapeutic effects of conventional NSAIDs are derived from the inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, whereas adverse effects on the upper gastrointestinal tract arise from inhibition of COX-1 activity. The risk of developing upper gastrointestinal bleeding and peptic ulcer disease is lower with coxibs than conventional NSAIDs14,15. Coxibs selectively inhibit COX-2, thereby inhibiting inflammation while preserving most of the homeostatic functions of COX-derived prostaglandins16. No difference in pain efficacy has been identified between different NSAIDs, including selective versus non-selective COX-2 inhibiting NSAIDs 13. The current recommended dose of celecoxib is 200 mg/day for long-term use in Japan and 400 mg/day in Western countries.

Despite its widespread use, very low-quality evidence exists for paracetamol as a treatment option for CLBP; therefore, recommendations are contradictory among guidelines12,17. A nonrandomized observational study suggested that paracetamol has analgesic effects equivalent to NSAIDs in patients with CLBP18. Only two trials have compared the effects of paracetamol with other drugs for CLBP19,20. First, Hickey compared treatment efficacy over 4 weeks between paracetamol (1,000 mg 4 times daily) and diflunisal (500 mg twice daily) in 1982, with 30 CLBP participants. They reported significantly superior treatment efficacy for diflunisal compared to paracetamol; however, the outcome relied on patient-reported ratings of treatment efficacy, ranging across four categories from poor to excellent19. A small number of patients in each group experienced mild adverse effects. NSAIDSs acts by inhibition of COX-1 and COX-2, which leads to a decrease in synthesis of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins, but adverse effects do exist. Second, Bedaiwi showed superior efficacy of celecoxib (200 mg twice daily) compared with paracetamol (500 mg twice daily) over 4 weeks of treatment in 2016, with 50 CLBP participants20. Demonstrating the superiority of celecoxib had significant implications; however, this study had some limitations. First, the administered dose of paracetamol (500 mg twice daily) was relatively low compared to that in real-world medicine20. The recommended maximum daily dose of paracetamol in adults is less than 4,000 mg17. Among the elderly, treatment with high-dose (> 3,000 mg per day) paracetamol is associated with a greater risk of hospitalization as a result of gastrointestinal perforation, ulceration, or bleeding compared to low-dose paracetamol (≤ 3,000 mg per day)21. Second, they investigated only the superiority of NSAIDs over paracetamol in CLBP. A non-inferiority trial22,23 has not been conducted to determine whether paracetamol is an alternative to NSAIDs for CLBP.

Thus, this randomized controlled study aimed to compare the analgesic effects of paracetamol (1,000 mg three times daily) and celecoxib (100 mg twice daily) in a non-inferiority trial. This non-inferiority trial tested the hypothesis that paracetamol is as effective as celecoxib for the treatment of CLBP within a pre-specified non-inferiority margin.

Methods

Participants

Participants were consecutively recruited from seven outpatient clinics in Japan (Nakae Hospital, Yukioka Hospital, Hayaishi Hospital Center for Pain Management, Hayaishi Hospital Orthopedics, ISEIKAI International General Hospital, Matsubara Mayflower Hospital, and Yoshida Medical Clinic) between June 2023 and 2024. Patients were eligible if they (1) were \(>\) 20 years and (2) had persistent low back pain for a minimum duration of 6 months prior to enrollment in the study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) uninterested in participation; (2) tumor-related pain, presence of neurological symptoms, or C-reactive protein level > 10 mg/dL; (3) within 3 months after surgery; and (4) taking medication associated with dementia. They were allowed to take their regular long-term medication or treatment for certain diseases, but not for pain. All the inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed by the referring physicians.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hayaishi Hospital (Mar 17th, 2019) (reference number, R010517-01), and all study participants provided written informed consent. All experiments were registered (UMIN000039719, Mar 7th, 2020, https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr/ctr_view_his.cgi). This study was performed in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of CONSORT statement and Declaration of Helsinki.

Randomization and treatment

This was a multicenter, open-label, randomized, assessor-unblinded, non-inferiority clinical trial. The patients were randomly divided into 2 equal groups using computer generation: the paracetamol group received 1,000 mg paracetamol tablets 3 times daily (3,000 mg per day) for 4 weeks (Calonal Tablet, Asympti Pharmaceutical Corp., Tokyo, Japan), and the celecoxib group received 100 mg celecoxib tablets 2 times daily (200 mg per day) for 4 weeks (Celecox Tablet; Astellas Pharmaceutical Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Treatment was performed by orthopedic doctors throughout the study, and a person who was not involved in treating the patients performed the randomization. The physicians instructed the patients that they could stop the medication if their symptoms improved or if any adverse effects related to the gastrointestinal tract, liver toxicity, or other adverse effects occurred during the period of the study.

Primary outcome

Outcome measures were assessed at baseline and at weeks two and four after starting the medication. The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) was used as the primary outcome measure of pain severity in each assessment, where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain.

Secondary outcome

Secondary outcomes were measured using the following questionnaires: the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Pain Disability Assessment Scale (PDAS), and EuroQol-5 Dimensions-3 level (EQ-5D-3L). All of these questionnaires were previously validated in Japanese and have shown good reliability among patients with CLBP24.

-

(i)

PCS

The PCS score consists of 13 items in which respondents rate the frequency of pain-related thought and emotions they have experienced5,6. The total PCS score ranged from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating higher levels of catastrophizing.

-

(ii)

HADS

HADS is designed to assess two separate dimensions: anxiety and depression7,8. The HADS consists of 14 items with anxiety (HADS-Anxiety) and depression (HADS-Depression) subscales, each including 7 items. A four-point response scale (from 0 representing absence of symptoms to 3 representing maximum symptoms) was used, with possible scores for each subscale ranging from 0 to 21.

-

(iii)

PDAS

The PDAS assesses the degree to which chronic pain interferes with various daily activities during the past week9. The PDAS includes 20 items reflecting pain interference in a broad range of daily activities, and respondents indicate the extent to which pain interferes. The total PDAS scores ranged from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher levels of pain interference.

-

(iv)

EQ-5D-3L

The EQ-5D-3L assesses self-reported health-related quality of life (QOL)10. The EQ-5D-3L defines health according to 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. The EQ-5D-3L index score range from − 0.111 to 1.000, where negative scores indicate health states worse than death, 0 represents death, and 1.000 represents full health.

-

(v)

Adverse effects

Adverse events were assessed simultaneously at two and four weeks. When subjects reported possible adverse events while taking the medication, they were instructed to withdraw or decrease the medication dosage depending on their condition.

Statistical analysis

Prior to sample size estimation, we determined the non-inferiority margin in the NRS between paracetamol and celecoxib. According to previous studies on CLBP, the mean change in pain intensity over a 4-week period was 1.6, with a standard deviation of 2.320. Since the NRS was used to assess the primary outcome in this study, the non-inferiority margin was defined as 0.313. Based on these values, at least 51 subjects per arm were required, with a type I error of 5% and 80% power. Given the expected dropout rate25, 156 patients with CLBP were randomly allocated to receive treatment with paracetamol or celecoxib.

We initially tested whether the data were normally distributed using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test for continuous variables. Between-group comparisons at each time point were conducted using either unpaired t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests, depending on data distribution Analyses were adjusted for baseline covariates and reported with means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Categorical variables were represented as the number and percentage of patients, and were analyzed using the χ2 test. Changes over time were analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA and post hoc tests. We then tested the following null (H0) and alternative (H1) hypotheses as MP: mean changes in NRS from baseline to weeks two and four with paracetamol, MC: mean changes in NRS from baseline to weeks two and four with celecoxib, and δ: non-inferiority margin;

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 28.0, for Microsoft Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

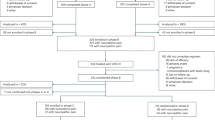

A flowchart of the dispositions of the participants is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, 156 consecutive patients with CLBP were randomized equally to receive either paracetamol or celecoxib. Of the 156 patients, 17 patients (10.9%) were lost to follow-up (paracetamol: 8, versus celecoxib: 9) and 139 patients (89.1%) completed the study (paracetamol: 70, versus celecoxib: 69). The dropout rate was not significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.797). As shown in Table 1, the NRS, PCS, HADS-Depression, and EQ-5D-3L variables showed no significant differences between the two medication groups at baseline. The paracetamol group had significantly worse PDAS and HADS-Anxiety scores than did the celecoxib group at baseline.

Figure 2 shows the mean and its 95% CI for the difference in changes in NRS from baseline to each follow-up point between the two medication groups. Using these analyses, the null hypothesis—that paracetamol is at least 0.3 points less effective than celecoxib on the NRS—was rejected at each follow-up point, respectively. Therefore, we cocluded that paracetamol was non-inferior to celecoxib within the predefined 0.3-point non-inferiority margin on the NRS.

Mean differences in NRS change scores from baseline to each follow-up between the paracetamol and celecoxib groups. The mean and its 95% confidence interval show the treatment difference of paracetamol compared to celecoxib. Paracetamol was as effective as celecoxib within at least a 0.3 points difference on NRS.

Table 2 shows changes in values of the primary and secondary outcomes. Scores at weeks two and four showed significant improvements than at baseline for each outcome in the paracetamol group. In the celecoxib group, scores for NRS and PCS improved significantly, whereas PDAS, HADS-Anxiety, HADS-Depression, and EQ-5D values showed no significant changes from baseline. There were no statistical differences in changes in NRS or PCS between the two medications at weeks two and four, even after covariate adjustment. The PDAS, HADS-Anxiety, and HADS-Depression values in the paracetamol group were significantly decreased compared with the celecoxib group at weeks two and four. The EQ-5D-3L value in the paracetamol group was significantly increased compared with the celecoxib group at week 4.

Contrastingly, although adverse effects were observed more frequently in the celecoxib group (6 of 69, 8.6%) compared to the paracetamol group (2 of 70, 2.8%), the overall incidence showed no significant difference between the 2 medications (Table 3). No patients discontinued or adjusted their medication due to adverse events.

Discussion

Overview

The present randomized open-label non-inferiority trial investigated whether paracetamol was as effective as celecoxib for CLBP within a specified non-inferiority margin over four weeks of treatment in outpatient clinics. We found that the mean difference in changes in NRS between the two medication groups did not statistically exceed the non-inferiority margin, suggesting that paracetamol has a comparable analgesic effect on CLBP within a 0.3 point margin on a 0–10 point NRS compared with celecoxib.

Clinical trials of paracetamol for CLBP

However, the efficacy of each drug in the treatment of CLBP remains uncertain13. Pharmacological therapy for CLBP often uses NSAIDs, paracetamol, opioids, antidepressants, and skeletal muscle relaxants; however, guideline recommendations are contradictory12,17. Paracetamol, one of the oldest and most commonly used analgesics, was introduced to the pharmacological market in 195526. Nevertheless, findings regarding paracetamol for CLBP are few and contradictory17,18,19,20. Previous studies have suggested a significantly superior treatment efficacy of NSAIDs compared with paracetamol17,18,19,20. The present study suggests that paracetamol has analgesic effects comparable to those of celecoxib. The dose of paracetamol (3,000 mg/day) in the present study was higher than that used in a previous trial (1,000 mg/day)20.

Mechanisms and adverse events of paracetamol

The mechanism of action is complex and includes the effects of both peripheral and central antinociceptive processes and redox mechanisms17,26. Recent studies emphasize that paracetamol may reduce pain through neurochemical changes in the central nervous system27,28. Interestingly, the present study suggested that paracetamol has a superior effect on pain-related psychological variables and QOL in the secondary outcomes compared with celecoxib at weeks 2 and 4. However, there is a lack of research on the efficacy and mechanisms of action of paracetamol17,26,28.

Paracetamol is known to have few adverse effects in the gastrointestinal tract17,26. However, cases of paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity26 and hospitalizations21 have been reported. However, there is a risk of serious adverse effects when regular and large doses of paracetamol are administered26. In the present study, the incidence of gastrointestinal adverse events was rare (2 of 70, 2.8%) with administration of paracetamol at 3,000 mg per day in the present study.

Several clinical trials have suggested a limited analgesic effect of paracetamol for patients with various diseases12,17,29,30. That is, for acute low back pain, there is high-quality evidence that paracetamol (4,000 mg per day) is no better than placebo for relieving pain in either the short or long term12,17. For knee or hip osteoarthritis, the efficacy of paracetamol (4,000 mg per day) was equal to or less than celecoxib (200 mg per day)29,30. These studies suggest that the efficacy of paracetamol could be disease-specific, even at maximal doses (4,000 mg/day)15.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the open-label and assessor-unblinded design of this clinical trial may have increased the risk of trial bias. Efficacy was compared between paracetamol and celecoxib groups, but not a placebo group. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution. This study included patients with both primary and secondary low back pain. Further studies with rigorous patient selection may provide more useful findings.

Conclusions

The present randomized controlled clinical trial suggested that the mean difference in changes in NRS over four weeks between the two medication groups did not statistically exceed the specified non-inferiority margin, suggesting that paracetamol provides analgesic effects comparable to celecoxib for CLBP.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

References

Nicholas, M. et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic primary pain. Pain 160(1), 28–37 (2019).

Meucci, R. D., Fassa, A. G. & Faria, N. M. X. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Rev. Saude Publica 49, 73 (2015).

Wong, C. K. et al. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with non-specific chronic low back pain in community-dwelling older adults aged 60 years and older: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pain. 23, 509–534 (2022).

Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, Chou R, Cohen SP, Gross DP, Ferreira PH, Fritz JM, Koes BW, Peul W, Turner JA, Maher CG; Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 391:2368–2383 (2018).

Sullivan, M. J. L., Bishop, S. R. & Pivik, J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 7, 524–532 (1995).

Matsuoka, H. & Sakano, Y. Assessment of cognitive aspect of pain: Development, reliability, and validation of Japanese version of pain catastrophizing scale. Jpn. J. Psychosom. Med. 47, 95–102 (2007).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67, 361–370 (1983).

Kugaya, A., Akechi, T., Okuyama, T., Okamura, H. & Uchitomi, Y. Screening for psychological distress in Japanese cancer patients. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 333–338 (1998).

Yamashiro, K. et al. A multidimensional measure of pain interference: Reliability and validity of the pain disability assessment scale. Clin. J. Pain. 27, 338–343 (2011).

Dolan, P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med. Care. 35, 1095–1108 (1997).

Wong, J. J. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur. J. Pain. 21, 201–216 (2017).

Oliveira, C. B. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: an updated overview. Eur. Spine J. 27, 2791–2803 (2018).

Enthoven, W. T., Roelofs, P. D., Deyo, R. A., van Tulder, M. W. & Koes, B. W. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD012087 (2016).

Lin, X. H. et al. Risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking selective COX-2 inhibitors: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Pain Med. 19, 225–231 (2018).

Rostom, A. et al. Gastrointestinal safety of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a Cochrane Collaboration systematic review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 818–828 (2007).

Silverstein, F. E. et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: A randomized controlled trial, celecoxib long-term arthritis safety study. JAMA 284, 1247–1255 (2000).

Saragiotto, B. T. et al. Paracetamol for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD012230 (2016).

Inoue, G. et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for patients with chronic low back pain: A nationwide, multicenter study in Japan. Spine Surg. Relat. Res. 5, 252–263 (2020).

Hickey, R. F. Chronic low back pain: a comparison of diflunisal with paracetamol. N Z Med J. 95, 312–314 (1982).

Bedaiwi, M. K. et al. Clinical efficacy of celecoxib compared to acetaminophen in chronic nonspecific low back pain: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 68, 845–852 (2016).

Rahme, E., Barkun, A., Nedjar, H., Gaugris, S. & Watson, D. Hospitalizations for upper and lower GI events associated with traditional NSAIDs and acetaminophen among the elderly in Quebec, Canada. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103, 872–882 (2008).

Oczkowski, S. J. A clinician’s guide to the assessment and interpretation of noninferiority trials for novel therapies. Open Med. 8, e67-72 (2014).

Walker, E. & Nowacki, A. S. Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 192–196 (2011).

Suzuki, H. et al. Clinically significant changes in pain along the Pain Intensity Numerical Rating Scale in patients with chronic low back pain. PLoS ONE 15, e0229228 (2020).

Miki, K. et al. Randomized open-labbel non-inferiority trial of acetaminophen or loxoprofen for patients with acute low back pain. J Orthop. Sci. 23, 483–487 (2018).

Jóźwiak-Bebenista, M. & Nowak, J. Z. Paracetamol: mechanism of action, applications and safety concern. Acta Pol. Pharm. 71, 11–23 (2014).

Tully, J. & Petrinovic, M. M. Acetaminophen study yields new insights into neurobiological underpinnings of empathy. J. Neurophysiol. 117, 1844–1846 (2017).

Mischkowski, D., Crocker, J. & Way, B. M. From painkiller to empathy killer: acetaminophen (paracetamol) reduces empathy for pain. Soc. Cogn. Affect Neurosci. 11, 1345–1353 (2016).

Geba GP, Weaver AL, Polis AB, Dixon ME, Schnitzer TJ; Vioxx, Acetaminophen, Celecoxib Trial (VACT) Group. Efficacy of rofecoxib, celecoxib, and acetaminophen in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized trial. JAMA. 287:64–71 (2002).

Pincus, T. et al. Patient Preference for Placebo, Acetaminophen (paracetamol) or Celecoxib Efficacy Studies (PACES): two randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, crossover clinical trials in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 63, 931–939 (2004).

Acknowledgements

There are no funders to report for this submission. The authors thank Nakae hospital, Yukioka hospital, Hayaishi hospital center for pain management, Hayaishi hospital orthopedics, ISEIKAI International General Hospital, Matsubara mayflower hospital, and Yoshida Medical Clinic for their cooperation. The authors also thank Dr. Kosuke Okuda, Dr. Shinichi Nakagawa, Dr. Satoshi Nakae, Dr. Ken Yoshida, Dr. Yasuhisa Hayaishi, and Dr. Kenji Ichiji for their contributions to the data collection.

Funding

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the following: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) final approval of the version to be published. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashi, K., Miki, K., Ueno, H. et al. Randomized open-label non-inferiority trial of paracetamol or celecoxib for patients with chronic low back pain. Sci Rep 16, 1577 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31094-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31094-y