Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurological disorder. The research has found that G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) may affect the pathogenesis of PD. This study aimed to explore the value of GPCRs-related genes (GPCRs-RGs) with PD. In this study, the PD, control samples, and GPCRs-RGs were obtained from the public database. Then, the candidate genes were identified through differential expression genes obtained from differential expression analysis and GPCRs-RGs. Subsequently, biomarkers were obtained through machine learning, expression analysis, and ROC analysis. Notably, the nomogram, regulatory network, and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of biomarkers were explored. In addition, a clustering analysis was adopted based on the biomarkers, and the immune infiltration were analyzed between the clusters. Finally, the expressions of biomarkers were further validated in clinical samples by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). This study identified NTSR1 and GPR161 as biomarkers associated with GPCRs and constructed a nomogram with good predictive ability with PD. The GSEA found 26 common pathways, such as oxidative phosphorylation enriched by NTSR1 and GPR161. Furthermore, the PD samples were divided into PD1 and PD2. Biomarkers were upregulated in PD1, while the scores of the 10 immune cells, such as mast cells and monocytes, in PD 1 were lower than PD 2. Finally, six drugs, such as sorafenib, 10 proteins, such as ARRB1 and ARRB2, and 15 miRNAs, such as hsa-miR-140-5p were found to be associated with biomarkers. The RT-qPCR results showed that biomarkers were downregulated in the PD group, which was consistent with the bioinformatics analysis results. NTSR1 and GPR161 were identified as novel biomarkers associated with GPCRs in PD. These might serve as potential therapeutic targets and provide new ideas for disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder with a rising rate worldwide and is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN)1. The clinical features of PD include motor symptoms, such as bradykinesia, resting tremor, muscle rigidity, and postural instability, as well as non-motor symptoms, such as sensory abnormalities, sleep disturbances, mental disorders, and autonomic dysfunctions2. Therefore, the daily activities of PD patients are severely affected, prominently increasing the burden on families and society. Currently, treatments for PD include both non-pharmacological and pharmacological therapies. Non-pharmacological therapies, such as rehabilitation training, exhibit efficacy that is contingent upon individualized implementation. The main pharmacological therapy for PD is to enhance dopamine nerve transmission, which effectively alleviates motor and nonmotor symptoms. However, these therapeutic agents fail to arrest the neurodegenerative progression and are associated with significant long-term adverse effects3,4. Thus, strategies for further treatment targets are still urgently needed.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as heptahelical or 7-transmembrane receptors, are a large class of cell membrane protein in humans and multiple other species5. GPCRs can identify a large amount of extracellular and inhibiting or activating downstream signaling cascades in the cell6. Stimulation of GPCRs also initiates the function of heterotrimeric G proteins and associated intracellular signaling pathways. Furthermore, beyond their signaling through heterotrimeric G proteins, GPCRs may regulate downstream effector pathways via interactions with various small G proteins5. Existing studies have demonstrated that certain GPCRs act as regulators of microglial activation, thereby modulating the impact of neuroinflammation on the pathophysiology of PD7. Interestingly, CPSRs are highly druggable targets focused on a broad range of therapeutic areas, and over 700 approved drugs target this receptor family8. Furthermore, studies have found the correlation of pharmacological modulation of some specific GPCRs for PD symptomatic therapy. Beyond dopamine receptors, many other GPCRs may provide potential non-dopaminergic therapeutic alternatives for treating PD by regulating the neural circuits affected by PD9.

Based on the public database, our study aimed to find novel biomarkers associated with GPCRs in PD through machine learning, expression analysis, and ROC analysis.

We further investigated the biological functions, differences in immune infiltration, and clinical utility of the acquired biomarkers. Several public databases were used to obtain the potential proteins, miRNAs, and drugs associated with the biomarkers. These results provide insights into molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies, which offer great promise for the development of new and personalized treatments for PD.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and sequencing

The tissue samples of PD in the GSE49036 and GSE26927 datasets were downloaded and viewed from the GEO database. The GSE49036 dataset, which used the GPL570 sequencing platform, includes 15 PD samples and 8 normal samples. The GSE26927 dataset, which was based on the GPL6255 sequencing platform, comprised 12 PD samples and 8 normal samples. 1,045 GPCRs-RGs were obtained from the MSigDB, and 394 GPCRs-RGs were obtained from the previous research10. These genes were merged for analysis.

Differential expression analysis in the GSE49036 dataset

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PD and control samples in the GSE49036 dataset were identified based on the “limma” R package (v 3.54.0)11, and the criteria were P < 0.05 & |log2 Fold Change (FC)| > 0.5. The top 10 up-regulated and down-regulated DEGs, sorted by the |log2FC| values, were marked by volcano plot and heat plot, which were made use of “ggplot2” package (v 3.4.4)12 and “ComplexHeatmap” package (v 2.14.0)13, respectively. Then, the intersection of DEGs and GPCRs-RGs was taken to obtain the candidate genes for this study by “VennDiagram” R package (v 1.7.3)14.

Enrichment analysis and PPI network

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of candidate genes were operated using the “clusterProfiler” R package (v 4.7.1.003)15 to explore the biological functions and pathways (P < 0.05). The GO includes three parts: molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and biological process (BP). Ulteriorly, to investigate the interactions between encoded proteins of candidate genes, the STRING database was borrowed to construct a PPI network (confidence score > 0.7), and the results were visualized through Cytoscape software (v 3.10.2)16.

Acquisition of biomarkers

To obtain the candidate biomarkers, LASSO and SVM-RFE algorithms were applied in this study. We used the “glmnet” R package (v 4.1.4)17 to build the LASSO model, and the feature genes were obtained based on 10-fold cross-validation (lambda best = lambda min). The SVM-RFE algorithm was implemented by the “caret” R package (v 6.0–93)18, which obtained feature genes by finding the optimal combination with the lowest error rate. The candidate biomarkers were acquired from the intersection of the two feature gene sets by the “VennDiagram” R package. To evaluate the diagnostic value of the candidate biomarkers, an ROC curve was plotted in the GSE49036 and GSE26927 datasets by the “pROC” R package (v 1.18.0)17, while the AUC greater than 0.7 as the filtering threshold. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon test assessed the expression level analysis, which required that the expression trends of genes between the PD and control groups in the two datasets were consistent and significant (P < 0.05).

Construction and evaluation of nomogram

To assess the prediction of PD risk by biomarkers, a nomogram was constructed by the “rms” R package (v 6.5.0)19 based on the biomarkers in the GSE49036 dataset. The calibration curve was also obtained by the “rms” R package to assess the accuracy of prediction results with nomogram (P > 0.05, MAE < 0.1). Finally, the DCA was implemented by the “rmda” R package (v 1.6)20 to evaluate the clinical utility of the nomogram.

GSEA analysis

The GSEA was conducted to understand the biological function of biomarkers implicated in PD progression in this study. Firstly, the Spearman correlation coefficients between biomarkers and all genes were calculated in the disease samples of the GSE49036 dataset. Afterward, the genes were arranged in descending order of correlation coefficient, and then the GSEA on each biomarker was performed by “clusterProfiler” R package (FDR < 0.05). In this analysis, the “c2.cp.kegg.v7.4.symbols.gmt” from the MSigDB was selected as the reference gene set, and the top 5 pathways based on the FDR values of each biomarker were visualized by “enrichplot” R package (v 1.18.3)21.

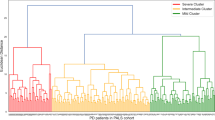

Analysis of consensus cluster

Based on the biomarkers identified above, the “Consensus Cluster Plus” R package (v 1.65.0)22 was used to conduct consensus cluster analysis, and the PD samples in the GSE49036 dataset were divided into different clusters by the k-means algorithm with the cycle computation of 1,000 times. The expression of biomarkers was performed between the different clusters according to the previously referenced method (P < 0.05). In order to evaluate the differences in biological function between different clusters, GSVA was completed by the “GSVA” R package (v 1.46.0)23 (P < 0.05), and the “c2.cp.kegg.v7.5.1.symbols.gmt” from the MSigDB database was selected as the reference gene set. Moreover, GSEA was also conducted to evaluate the differences in biological function with the DEGs in the different clusters. In this process, the “limma” R package was used primarily to acquire the DEGs in the different clusters, and then the “clusterProfiler” R package was applied to perform GSEA with the DEGs (FDR < 0.25, P < 0.05 and |NES|) > 1).

The analysis SsGSEA for 28 immune cells

The immune cell infiltration was brought into by ssGSEA for 28 immune cells24 in GSE49036. Then, the differences in immune cells between different clusters were compared by the Wilcoxon test (P < 0.05). Besides, the relationship between biomarkers and immune cells was carried out using Spearman correlation analysis by “psych” R package (v 2.2.9)25. (|cor| > 0.3, P < 0.05).

Prediction of proteins, miRNAs, and drugs

Several public databases were included in this study to identify proteins, miRNAs, and drugs associated with biomarkers. The STRING database was used to obtain interaction protein (combined score > 0.75), the miRwalk was used to predict the microRNAs (miRNA), and the DGIdb dataset was adopted to scour the drug with biomarkers. based on the above results, A network was constructed by Cytoscape software (v 3.9.1)16.

The assessment of biomarkers expression

The assessment of biomarker expression was conducted on clinical blood samples using RT-qPCR. A total of 5 pairs of blood samples were obtained from Guangxi Jiangbin Hospital, including 5 PD and 5 control. All participants needed to sign and fill out the informed consent form. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jiangbin Hospital (LW-2025-007). Firstly, the total RNA of 5 pairs of tissue samples was derived by TRizol reagent (Vazyme, China). The RNA concentrations were computed by NanoPhotometer N50. Secondly, mRNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA utilizing a SureScript-First-strand-cDNA-synthesis-CREB5B test kit (Yesen, Shanghai, China). Finally, the RT-qPCR was conducted. The expression levels of biomarkers between PD and control samples were calculated by 2−ΔΔCt, and the expression differences of these genes were measured by the student’s t-test (P < 0.05). The internal reference gene was GAPDH, which was employed to normalize the results. Finally, GraphPad Prism 5 (v 8.0)26 was adopted to achieve statistical analysis and visualization. Detailed information on primers and machine testing conditions is listed in Table S6.

Statistical analyses

Bioinformatics analyses were performed using the R programming language (v 4.2.2). Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the differences between the two groups. P < 0.05 represented statistically significant.

Results

Identification and exploration of candidate genes

In the GSE49036 dataset, a total of 1,355 DEGs were identified. The 906 genes behind them were upregulated, and 449 were down-regulated in the PD group compared to the control sample (Fig. 1a). After that, 61 candidate genes were obtained by the intersection of DEGs and GPCRs-RGs (Fig. 1b).

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of PD in GSE49036. (a) Volcano plot of all DEGs. Red nodes indicate upregulated DEGs, green nodes indicate downregulated DEGs, and gray nodes indicate genes that are not significantly differentially expressed. (b) Venn diagram of DEGs and G protein-coupled receptors-related genes (GPCRs-RGs)

In GO analysis of the candidate genes, 287 BP pathways, 45 CC pathways, and 46 MF pathways were obtained. In terms of BP, such adenylate cyclase-modulating G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathways were enriched with the genes. In CC, candidate genes were significantly enriched in the dendritic spine and neuron spine. In MF, G protein-coupled peptide receptor activity and GTPase activator activity were the top three enrichment pathways (Fig. 2a) (Table S1). Subsequently, the 61 candidate genes were enriched in 74 pathways, such as the phospholipase D signaling pathway, upon KEGG pathway analysis (Fig. 2b) (Table S2).

The PPI network is crucial for comprehending the structure and function of cellular networks and the basis for the occurrence and development of diseases27. The PPI results indicated that 39 genes had an interactive relationship after removing isolated genes. Among them, GNB5 and GNA13 had interaction relationships with multiple genes (Fig. 3).

Identification of NTSR1 and GPR161 as biomarkers

Based on the 39 genes from the PPI network, LASSO and SVM-RFE algorithms were used to obtain the candidate biomarkers. In LASSO model, 8 genes such as ARRB1, CXCR2, NTSR1, GPR161, PIK3CA, HTR2A, LPAR5, CXCL12 were selected while the thresholds was lambda=−2.5846. (Fig. 4a, b). In the SVM-RFE model, 16 genes were selected (Fig. 4c). Finally, three candidate biomarkers, ARRB1, NTSR1, and GPR161, were obtained from the intersection between the two algorithms (Fig. 4d).

In the GSE49036 and GSE26927 datasets, only two candidate biomarkers had significant differences in expression and consistent trends (Fig. 4e, f), while the AUC of them was also greater than 0.7 (Fig. 4g, h). So the two genes (NTSR1, GPR161) were regarded as biomarkers.

High accuracy of the nomogram

As shown in Fig. 5a, a nomogram was created based on the expression of NTSR1 and GPR161 to predict the prevalence of PD in patients. The calibration curves revealed that the nomogram had high accuracy in predicting PD (P = 0.506, MAE = 0.079) (Fig. 5b). The net benefit of biomarkers and nomograms in the DCA curve was better than that in the None, which indicated that decision-making based on the nomogram could benefit patients with PD (Fig. 5c).

Enrichment pathways of biomarkers

The signaling pathways link to NTSR1 and GPR161 via GSEA. The results showed that the number of significant pathways enriched by NTSR1 and GPR161 were 32 and 34, respectively, while the top 5 signaling pathways were displayed in Fig. 6a and b (FDR < 0.05) (Table S3 and S4). NTSR1 and GPR161 were significantly correlated with 26 common pathways, such as oxidative phosphorylation, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, cardiac muscle contraction, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), proteasome, and pathways in cancer.

Immune cells associated with biomarkers

As shown in Fig. 7a-c, the highest correlation was observed within the community, while intergroup correlations were minimal when k = 2. Consequently, the PD samples in the GSE49036 data were divided into two clusters (PD1 and 2). The differential expression analysis showed that both NTSR1 and GPR161 were highly expressed in PD1, and the results were significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7d). Moreover, the scores of 10 kinds of immune cells were significantly different (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7e). The scores of the 10 cells (activated B cells, CD56 bright natural killer cells, effector memory CD8 T cells, mast cells, monocytes, natural killer T cells, natural killer cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, T follicular helper cells, and type 17 T helper cells) in PD1 were all lower than PD 2. The correlations analysis showed that NTSR1 was negatively correlated with activated B cells (cor = −0.56, P = 0.03), mast cell (cor = −0.56, P = 0.03), CD56 bright natural killer cell (cor = −0.54, P = 0.04) and effector memory CD8 T cell (cor = −0.54, P = 0.04) while GPR161 was negatively correlated with natural killer cell (cor = −0.66, P = 0.01), T follicular helper cell (cor = −0.64, P = 0.01), effector memeory CD8 T cell (cor = −0.63, P = 0.01), monocyte (cor = −0.61, P = 0.02), activated B cells (cor = −0.60, P = 0.02), plasmacytoid dendritic cell (cor = −0.57, P = 0.03), CD56 bright natural killer cell (cor = −0.57, P = 0.03), and natural killer T cell (cor = −0.57, P = 0.03) (Fig. 7f, g) (Table S5).

Immune characteristics between two different immune patterns. (a) Consensus clustering matrix at k = 2. (b) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plot. (c) Relative change in area under CDF delta curves. (d) Expression levels of NTSR1 and GPR161 in the two clusters. (e) Boxplots of the immune score of each immune cell in the two clusters. Correlation analysis between immune cell content and GPR161 (f) and NTSR1 (g)

Different pathways in the two PD clusters

The results of GSVA indicated that various pathways, such as Parkinson’s disease, had an enrichment difference between the two clusters (Fig. 8a). In addition, the results of GSEA showed that the DEGs in PD1 and 2 were significantly enriched in multiple pathways, such as synaptic vesicle cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, and pathways of neurodegeneration-multiple diseases (Fig. 8b).

Drugs, proteins, and MiRNAs associated with biomarkers

As shown in Figs. 9a and 15 miRNAs were found to be associated with biomarkers. The miRNAs related to GPR161 include hsa-miR-140-5p and hsa-miR-373-3p, while those related to NTSR1 include hsa-miR-149-3p and hsa-miR-6742-3p. Furthermore, 10 proteins were found to be associated with biomarkers, of which β-arrestin 1 (ARRB1) and β-arrestin 2 (ARRB2) were associated with both biomarkers (Fig. 9b). The drugs associated with NTSR1 included meclinertant, sorafenib, thimerosal, chembl548458, chembl493863, and chembl532160 (Fig. 9c). Variously, no drugs related to GPR161 were predicted. These results indicated that the above proteins, drugs, and miRNAs also potentially affect on PD.

The expression analysis of biomarkers in the clinical samples

As shown in Figs. 10a and b, the RT-qPCR results showed that the expression of GPR161 and NTSR1 had significant differences between controls and PD samples (P < 0.05). The expression of 2 biomarkers were all downregulated in the PD group. The results were consistent with the the bioinformatics analysis, indicating that preliminary results were reliable in our study.

Discussion

PD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons, leading to motor impairment. Although no treatment currently exists to halt the progression of PD, dopamine replacement therapy, including dopamine precursors, can alleviate motor symptoms28. However, treatment options for non-motor symptoms, such as neuropsychiatric disturbances and cognitive impairment, remain limited. GPCRs, which are highly druggable cell surface proteins, have been identified as potential disease-modifying targets with neuroprotective effects in PD29. In the present study, two key genes (NTSR1 and GPR161) were identified as being associated with GPCRs, demonstrating high accuracy in differentiating patients with PD from healthy controls. The expression of NTSR1 and GPR161 was further validated by RT-qPCR, confirming the results. Both biomarkers were significantly correlated with several pathways, including oxidative phosphorylation and PD. Additionally, the DEGs in the two PD clusters were notably enriched in multiple pathways, such as the synaptic vesicle cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. Moreover, 6 drugs, 10 proteins, and 15 miRNAs were identified as being associated with these biomarkers.

NTSR1, a canonical GPCR, signals through the neuropeptide neurotensin (NTS) to regulate various physiological processes, including blood pressure, blood glucose levels, body temperature, antinociception, and neuronal injury repair30. Its primary function is closely linked to the regulation of GPCR signaling pathways and is directly modulated by GRK2 and GRK5. NTSR1 has been validated as a critical pharmacological target for neurological diseases, including PD31,32. Extensive research has documented the role of NTSR1 in PD. Studies by Duan et al. demonstrated that activation of NTSR1 can initiate signaling pathways through the recruitment of GRK2. The arrestin-biased ligand SBI-553 exerts neuroprotective effects by activating the arrestin pathway. This receptor’s involvement in neuronal injury repair further supports its potential as a therapeutic target for PD33. GPR161 is another GPCR implicated in various intracellular signaling processes, influencing cellular physiological functions34. It has been linked to cancer pathogenesis and neurulation, though the underlying molecular mechanisms are not yet fully understood35,36. While direct studies of GPR161 in PD are limited, research in other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Huntington’s disease, suggests that alterations in GPR161 expression may contribute to disease pathogenesis, implying potential neuroprotective functions37. Given its role in cellular signaling and neurodevelopment, GPR161 may be indirectly involved in PD pathogenesis through the regulation of neural cellular homeostasis. This hypothesis warrants further investigation in future studies34.

An inverse correlation was observed between the expression levels of NTSR1/GPR161 and immune cells, such as activated B cells and CD56 bright natural killer cells. This finding offers crucial insights into the regulatory mechanisms of the PD immune microenvironment and highlights potential therapeutic targets. Previous studies have shown that changes in the count of B-lymphocytes and the percentage of regulatory B cells are linked to the progression of PD38. The downregulation of NTSR1 may lead to the derepression of activated B cells, thereby exacerbating the inflammatory cascade. Interestingly, GPR161 serves as a key negative regulator of the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway, and its aberrant activation is associated with dopaminergic neuronal repair in PD. Thus, the downregulation of GPR161 may result in excessive Shh pathway activation, which could influence immune cell infiltration34,39. Moreover, CD56 bright NK cells are elevated in PD and contribute to disease progression through the secretion of cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α, with their abundance correlating positively with PD severity40,41. The decreased expression of GPR161 correlates with an increase in CD56 bright NK cells, suggesting its role in modulating the infiltration of this cellular subset through signaling pathway regulation.

Beyond NTSR1 and GPR161, numerous studies have explored the roles of GPCR family members in neurodegenerative diseases. For example, reduced cortical muscarinic M1 receptor binding to G-proteins has been identified as a neurochemical alteration underlying the limited efficacy of presynaptic cholinergic replacement therapy in AD42. Additionally, genetic variations in the ADORA2A gene have been shown to influence the age of onset in Huntington’s disease43. These findings highlight the central regulatory role of GPCRs in neurodegenerative diseases and provide valuable context for investigating the functions of the two genes examined in this study.

The co-enrichment of NTSR1 and GPR161 in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway, as highlighted by the GSEA analysis, is of significant relevance. This suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction is prevalent in patients with PD, with impaired oxidative phosphorylation serving as a key mechanism contributing to the vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons44. NTSR1 is believed to sustain mitochondrial function by regulating energy metabolism in dopaminergic neurons, and its downregulation may worsen the decline in oxidative phosphorylation efficiency, leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent neuronal death45. Although direct evidence for GPR161’s involvement in mitochondrial dysfunction is lacking, it is hypothesized that disruptions in its signaling pathway may indirectly affect the mitochondrial respiratory chain, potentially acting synergistically with NTSR1 downregulation to exacerbate pathological damage46. The enrichment of pathways related to Huntington’s disease and AD further suggests that NTSR1 and GPR161 may be implicated in shared pathological mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases, such as protein misfolding and neuroinflammation47,48,49. Additionally, the enrichment of the cardiac muscle contraction pathway may be associated with autonomic nervous system dysfunction in patients with PD, indicating that the downregulation of these genes may also impact peripheral tissue function, providing molecular insights into the non-motor symptoms of PD50.

Based on the consensus clustering analysis of NTSR1 and GPR161, PD samples were divided into two distinct subgroups, PD1 and PD2. The relationship between these subgroups and established PD subtypes facilitates an exploration of disease heterogeneity. PD is widely recognized as a heterogeneous disorder with distinct subtypes51.

Patients with PD are commonly classified according to motor characteristics into tremor-dominant, akinetic-rigid, postural instability/gait difficulty (PIGD), and mixed subtypes. Among these, the PIGD subtype is associated with faster progression of both motor and cognitive decline52. Since the advent of PD subtyping research, various classification systems have been proposed, incorporating factors such as age and progression rate53. In the present study, the PD1 cluster showed significant enrichment in pathways related to PD, oxidative phosphorylation, and Huntington’s disease, along with high expression of NTSR1 and GPR161—key regulators of mitochondrial function. These findings suggest that the core pathology of the PD1 cluster involves mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction and impaired oxidative phosphorylation in dopaminergic neurons. Furthermore, the co-enrichment of neurodegenerative pathways indicates a clinical phenotype characterized by rapid motor symptom progression, primarily driven by disrupted energy metabolism. In contrast, the PD2 cluster demonstrated significant enrichment in inflammation-related pathways, including the complement and coagulation cascades, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, and leukocyte transendothelial migration. Immune infiltration analysis revealed lower immune cell levels in PD1, supporting the notion that the PD1 cluster is predominantly associated with an activated immune-inflammatory pathology.

As miRNAs are well-known post-transcriptional gene regulators involved in various pathological conditions. They bind to specific regions in the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR) of target mRNA, leading to translation suppression and degradation of the mRNA’s adenylation and capping structures54,55. Additionally, miRNAs can bind to other regions of mRNA, such as the 5’ UTR, coding sequence (CDS), and promoter regions55. While binding to the 5’ UTR or CDS typically represses gene expression, binding to the gene promoter region is associated with transcriptional activation56,57.

In this study, several miRNAs, including hsa-miR-140-5p and hsa-miR-149-3p, were identified as being associated with GPR161 and NTSR1. These findings offer new insights into the miRNA-mediated regulation of GPR161/NTSR1 in PD, providing valuable clues for further exploration of their regulatory mechanisms.

Hsa-miR-140-5p and hsa-miR-149-3p may suppress the expression of GPR161 and NTSR1 by binding to their 3’ UTRs or CDS, thereby diminishing neuroprotective effects and contributing to the pathological progression of PD. However, the potential regulatory interactions between these miRNAs and GPR161/NTSR1 need to be further validated. This validation should include confirming the binding sites through dual-luciferase reporter assays and investigating their specific effects on neuronal survival and inflammatory responses using cellular functional experiments.

In terms of protein interactions, ARRB1 and ARRB2 were found to be related to NTSR1 and GPR161. Previous studies have shown that ARRB1 and ARRB2 play opposing roles in PD pathogenesis, mediated in part by nitrogen permease regulator-like 3 (Nprl3). ARRB2 knockout exacerbates neuroinflammation, dopaminergic neuron loss, microglia activation in vivo, and neuron damage mediated by microglia in vitro, while ARRB1 ablation has protective effects58. Mendelian randomization studies also suggest that reduced ARRB2 expression is closely associated with an increased risk of PD59. These findings offer novel insights into PD pathogenesis and treatment strategies.

In this study, NTSR1 was used to predict drug-gene interactions, while no drugs were identified for GPR161. Six potential drugs were predicted for PD treatment, with sorafenib emerging as a ferroptosis inducer. Growing evidence suggests that iron deposition in the brain contributes to dopaminergic neuron degeneration60,61. Therefore, sorafenib may be considered a potential target for PD treatment. However, significant barriers remain in its clinical application, particularly with regard to its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Preclinical studies have shown that sorafenib has limited penetration through an intact BBB into brain tissue62. Given that PD therapies require precise drug delivery to specific brain regions, the insufficient concentration of sorafenib in the brain may undermine its neuroprotective efficacy.

Thimerosal (THIM) is a well-known oxidizing agent. Studies have demonstrated its neurotoxic effects, including dysfunction of the monoaminergic system. The THIM-induced tyrosine hydroxylase (DmTyrH) lesion impairs dopamine function and induces behavioral abnormalities, ultimately leading to oxidative stress-related neurotoxicity. Mitigating these neurotoxic effects could be beneficial in the prevention and treatment of PD. However, research on the roles of meclinertant, chembl548458, chembl493863, and chembl532160 in PD therapy remains limited. RT-qPCR experiments revealed that both NTSR1 and GPR161 were downregulated in the PD group, aligning with the results of bioinformatics analyses, thereby supporting the preliminary validity of this study.

As this study primarily involves bioinformatics analysis, it has certain inherent limitations. While no correlation was established between peripheral blood expression of GPCR-RGs and cerebral pathology, our findings complement existing PD biomarkers and provide a foundation for further exploration of the target genes. Additionally, the RT-qPCR validation phase included a relatively small sample size. Although the RT-qPCR results suggest that the expression trends of the target indicators align with prior findings, the limited sample size restricts the ability to offer a comprehensive and objective assessment of the markers’ true expression patterns in the target population. To overcome this limitation, further research will expand the validation cohort in future studies, using more stringent sample matching and incorporating power analysis for sample size estimation. This will enhance the statistical robustness and clinical relevance of the findings. Notably, the RT-qPCR results from this study are intended to provide preliminary insights into the target genes. Their definitive expression patterns and clinical significance will require further validation through independent, large-scale cohort studies.

In conclusion, this study identified NTSR1 and GPR161 as GPCR-related biomarkers in PD, offering novel approaches for disease diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, H. et al. Identification and experimental validation of parkinson’s disease with major depressive disorder common genes. Mol. Neurobiol. 60, 6092–6108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-023-03451-3 (2023).

Przedborski, S. The two-century journey of Parkinson disease research. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.25 (2017).

Connolly, B. S. & Lang, A. E. Pharmacological treatment of Parkinson disease: a review. JAMA 311, 1670–1683. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.3654 (2014).

Poewe, W. et al. Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 3, 17013. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.13 (2017).

Nakano, N. et al. PI3K/AKT signaling mediated by G protein–coupled receptors is involved in neurodegenerative parkinson’s disease (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 39, 253–260. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.2016.2833 (2017).

Li, H., Urs, N. M. & Horenstein, N. Computational insights into ligand-induced G protein and beta-arrestin signaling of the dopamine D1 receptor. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 37, 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10822-023-00503-7 (2023).

Gu, C. et al. Role of G Protein-Coupled receptors in microglial activation: implication in parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 768156. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.768156 (2021).

Sriram, K. & Insel, P. A. G Protein-Coupled receptors as targets for approved drugs: how many targets and how many drugs? Mol. Pharmacol. 93, 251–258. https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.117.111062 (2018).

Lemos, A. et al. In Silico studies targeting G-protein coupled receptors for drug research against parkinson’s disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 16, 786–848. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X16666180308161642 (2018).

Suteau, V. et al. Identification of dysregulated expression of G protein coupled receptors in endocrine tumors by bioinformatics analysis: potential drug targets? Cells 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11040703 (2022).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Gustavsson, E. K., Zhang, D., Reynolds, R. H., Garcia-Ruiz, S. & Ryten, M. ggtranscript: an R package for the visualization and interpretation of transcript isoforms using ggplot2. Bioinformatics 38, 3844–3846 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btac409

Gu, Z. Complex heatmap visualization. Imeta 1 (e43). https://doi.org/10.1002/imt2.43 (2022).

Chen, H. & Boutros, P. C. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform. 12, 35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-35 (2011).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287. https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0118 (2012).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1239303 (2003).

Wang, P. et al. Uncovering ferroptosis in parkinson’s disease via bioinformatics and machine learning, and reversed deducing potential therapeutic natural products. Front. Genet. 14, 1231707. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1231707 (2023).

Lopez-Diaz, J. O. M. et al. Dummy regression to predict dry fiber In Agave Lechuguilla Torr. In two large-scale bioclimatic regions In Mexico. PLoS One. 17, e0274641. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274641 (2022).

Li, M. et al. Recognition of refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia among Myocoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in hospitalized children: development and validation of a predictive nomogram model. BMC Pulm Med. 23, 383. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-023-02684-1 (2023).

Kerr, K. F., Brown, M. D., Zhu, K. & Janes, H. Assessing the clinical impact of risk prediction models with decision curves: guidance for correct interpretation and appropriate use. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2534–2540. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.65.5654 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Cuproptosis related genes associated with Jab1 shapes tumor microenvironment and Pharmacological profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 13, 989286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.989286 (2022).

Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics 26, 1572–1573. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170 (2010).

Zhao, P., Zhen, H., Zhao, H., Huang, Y. & Cao, B. Identification of hub genes and potential molecular mechanisms related to radiotherapy sensitivity in rectal cancer based on multiple datasets. J. Transl Med. 21, 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04029-2 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. Identification of aging-related biomarkers and immune infiltration characteristics in osteoarthritis based on bioinformatics analysis and machine learning. Front. Immunol. 14, 1168780. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1168780 (2023).

Robles-Jimenez, L. E. et al. Worldwide traceability of antibiotic residues from livestock in wastewater and soil: A systematic review. Anim. (Basel). 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12010060 (2021).

Chang, J. et al. Constructing a novel mitochondrial-related gene signature for evaluating the tumor immune microenvironment and predicting survival in stomach adenocarcinoma. J. Transl Med. 21, 191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04033-6 (2023).

Zeng, Y., Cao, S. & Chen, M. Integrated analysis and exploration of potential shared gene signatures between carotid atherosclerosis and periodontitis. BMC Med. Genomics. 15, 227. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01373-y (2022).

Reich, S. G. & Savitt, J. M. Parkinson’s disease. Med. Clin. North. Am. 103, 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2018.10.014 (2019).

Jones-Tabah, J. & Targeting, G. Protein-Coupled receptors in the treatment of parkinson’s disease. J. Mol. Biol. 435, 167927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167927 (2023).

Slosky, L. M. et al. beta-Arrestin-Biased Allosteric Modulator of NTSR1 Selectively Attenuates Addictive Behaviors. Cell 181, 1364–1379 e1314 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.053

Inagaki, S. et al. G Protein-Coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) and 5 (GRK5) exhibit selective phosphorylation of the neurotensin receptor in vitro. Biochemistry 54, 4320–4329. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00285 (2015).

Di Fruscia, P. et al. The discovery of Indole full agonists of the neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 24, 3974–3978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.06.033 (2014).

Duan, J. et al. GPCR activation and GRK2 assembly by a biased intracellular agonist. Nature 620, 676–681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06395-9 (2023).

Mukhopadhyay, S. et al. The ciliary G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr161 negatively regulates the Sonic Hedgehog pathway via cAMP signaling. Cell 152, 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.026 (2013).

Feigin, M. E., Xue, B., Hammell, M. C. & Muthuswamy, S. K. G-protein-coupled receptor GPR161 is overexpressed in breast cancer and is a promoter of cell proliferation and invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, 4191–4196. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320239111 (2014).

Li, B. I. et al. The orphan GPCR, Gpr161, regulates the retinoic acid and canonical Wnt pathways during neurulation. Dev. Biol. 402, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.02.007 (2015).

Wright, G. E. B. et al. Gene expression profiles complement the analysis of genomic modifiers of the clinical onset of huntington disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 29, 2788–2802. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddaa184 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Abnormal immune function of B lymphocyte in peripheral blood of parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 116, 105890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2023.105890 (2023).

Nair, S. V., Jaimon, E., Adhikari, A., Nikoloff, J. & Pfeffer, S. R. Lysosomal glucocerebrosidase is needed for ciliary Hedgehog signaling: A convergent pathway contributing to parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 122, e2504774122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2504774122 (2025).

Rodriguez-Mogeda, C. et al. The role of CD56(bright) NK cells in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Neuroinflammation. 21, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-024-03040-8 (2024).

Weber, S. et al. Distinctive CD56(dim) NK subset profiles and increased NKG2D expression in blood NK cells of parkinson’s disease patients. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 10, 36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-024-00652-y (2024).

Lee, J. H. et al. Muscarinic M1 receptor coupling to G-protein is intact in parkinson’s disease dementia. J. Parkinsons Dis. 6, 733–739. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-160932 (2016).

Dhaenens, C. M. et al. A genetic variation in the ADORA2A gene modifies age at onset in huntington’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 35, 474–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2009.06.009 (2009).

Singh, A., Kukreti, R., Saso, L. & Kukreti, S. Oxidative stress: A key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24081583 (2019).

Woodworth, H. L. et al. Neurotensin Receptor-1 identifies a subset of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons that coordinates energy balance. Cell. Rep. 20, 1881–1892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.001 (2017).

Shimada, I. S. et al. Derepression of Sonic Hedgehog signaling upon Gpr161 deletion unravels forebrain and ventricular abnormalities. Dev. Biol. 450, 47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2019.03.011 (2019).

Alqahtani, T. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in alzheimer’s disease, and parkinson’s disease, huntington’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis -An updated review. Mitochondrion 71, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mito.2023.05.007 (2023).

Peng, C., Trojanowski, J. Q. & Lee, V. M. Protein transmission in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 16, 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-020-0333-7 (2020).

Rauf, A. et al. Neuroinflammatory markers: key indicators in the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 27 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103194 (2022).

Cuenca-Bermejo, L. et al. Cardiac Changes in Parkinson’s Disease: Lessons from Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222413488 (2021).

Fereshtehnejad, S. M. & Postuma, R. B. Subtypes of parkinson’s disease: what do they tell Us about disease progression? Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 17, 34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0738-x (2017).

Potter-Nerger, M. et al. Serum neurofilament light chain and postural instability/gait difficulty (PIGD) subtypes of parkinson’s disease in the MARK-PD study. J. Neural Transm (Vienna). 129, 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-022-02464-x (2022).

Marras, C., Chaudhuri, K. R., Titova, N. & Mestre, T. A. Therapy of parkinson’s disease subtypes. Neurotherapeutics 17, 1366–1377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-020-00894-7 (2020).

Asadi, M. R. et al. Competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks in parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 17, 1044634. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2023.1044634 (2023).

Ipsaro, J. J. & Joshua-Tor, L. From guide to target: molecular insights into eukaryotic RNA-interference machinery. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2931 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. Oncogenic role of microRNA-532-5p in human colorectal cancer via targeting of the 5’UTR of RUNX3. Oncol. Lett. 15, 7215–7220. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.8217 (2018).

Dharap, A., Pokrzywa, C., Murali, S., Pandi, G. & Vemuganti, R. MicroRNA miR-324-3p induces promoter-mediated expression of rela gene. PLoS One. 8, e79467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079467 (2013).

Fang, Y. et al. Opposing functions of beta-arrestin 1 and 2 in parkinson’s disease via microglia inflammation and Nprl3. Cell. Death Differ. 28, 1822–1836. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-020-00704-9 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Combining Single-Cell RNA sequencing and Mendelian randomization to explore novel drug targets for parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-025-04700-3 (2025).

Qiu, Y., Cao, Y., Cao, W., Jia, Y. & Lu, N. The application of ferroptosis in diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 159, 104919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104919 (2020).

Costa, I. et al. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and their involvement in brain diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 244, 108373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108373 (2023).

Dudek, A. Z. et al. Brain metastases from renal cell carcinoma in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer. 11, 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clgc.2012.11.001 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all investigators for providing publicly summary data.

Funding

The authors declare that no fund support was received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection were performed by Yanfang Yun, Zhuohua Bao, Dingyue Peng and Zuoli Wu. Analysis and first draft of the manuscript were performed by Huadan Yang and Xiaoju Wu. Wei Zhang revised the manuscript and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Jiangbin Hospital (LW-2025-007).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, H., Wu, X., Yun, Y. et al. Identifying the biomarkers associated with G protein-coupled receptors of parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep 16, 1651 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31148-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31148-1