Abstract

Low-light color images are limited in their application in fields such as security monitoring and autonomous driving due to issues such as dim brightness and blurry details. To improve the problem of dim brightness and uneven local lighting in low-light color images, and to enhance image quality to meet practical application needs, this study adopts multi-frame grouping denoising and adaptive gamma correction to unify the brightness range, combined with blind source separation denoising and Pearson growth curve adjustment of brightness. To address uneven light in a single frame, dual-scale adaptive gamma correction are adopted. Comparative experiments are conducted with multiple sets of low-light and light uneven images to validate the performance of the research method. The findings denoted that the average brightness of the enhanced image increased from the original 5.03–25.31 to 57.14–80.02, the information entropy increased from 3.26 to 6.07 to 7.05–8.19, and the image processing time was only 2.47–2.55 s. In images with uneven lighting, the average gradient increased from 12.74 to 16.47 to 25.32–27.12, and the visual information fidelity reached 0.89–0.93. Full size processing could be completed in 85.06 ms. The research method effectively solves the problems of brightness fluctuations and local overexposure in low-light images, providing a reference path for low-light image applications in related fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s rapidly developing era of digitization and informatization, image information plays an increasingly crucial role in many fields. From security monitoring and social safety to precise recognition of road conditions by autonomous driving, the quality of images directly affects the accuracy of information acquisition and decision-making1. Low-light color images, obtained in environments with insufficient lighting, commonly suffer from issues such as dim brightness, blurry details, low contrast, and significant noise. Compared to images under normal lighting conditions, it brings many inconveniences and challenges to practical applications. Therefore, there is an urgent need for effective enhancement processing2. Traditional methods such as HE, although simple to operate, can easily lead to image over enhancement and noise amplification3. Gamma correction is difficult to adapt to the complex changes in brightness of multi-frames of images in different scenes due to fixed parameters4. However, some advanced algorithms based on deep learning, although improving the enhancement effect to a certain extent, often require massive labeled data for training and have extremely high hardware requirements, facing difficulties in promotion in practical applications5. Current research mainly focuses on improving overall brightness, with insufficient attention paid to issues such as uneven local lighting and collaborative processing of multi-frames of images. There is a lack of a systematic and efficient framework for processing low-light color images6. To address the issues of inconsistent brightness and poor image enhancement effect in low-light color images with uneven lighting, a research was conducted to unify the brightness range through multi-frame grouping denoising and adaptive gamma correction, and to enhance uneven lighting images through region partitioning and dynamic gamma index adjustment.

The innovations of this study are as follows: (1) It unifies brightness ranges through multi-frame grouped denoising and adaptive gamma correction. Unlike most recent deep learning methods that rely on large-scale annotated datasets and require demanding hardware resources, the proposed method eliminates the need for data annotation or complex model training, and can achieve uniform multi-frame image brightness even on standard hardware equipped with Intel Core i5 processors; (2) To address the common issues of excessive enhancement or detail loss in scenes with uneven local lighting, it combines YUV space blind source separation denoising with Peirce’s growth curve, an approach that precisely suppresses noise while maintaining smooth brightness adjustments; (3) For single-frame scenarios, it applies dual-scale region partitioning and an improved two-dimensional gamma function to dynamically match local brightness characteristics. Compared with the rigid feature fitting methods used in some deep learning approaches, this method offers better alignment with real-world light patterns.

The contribution of this study are as follows: (1) An efficient low-light image processing method is proposed that simultaneously corrects dim brightness and uneven illumination while suppressing noise amplification, local over-exposure and large brightness fluctuations that plague traditional techniques. (2) Tailored for single-frame, uneven-light conditions, the method realizes accurate brightness balancing that preserves fine details and suppresses noise, delivering both superior visual quality and high processing speed. (3) By supplying reliable, high-quality imagery for security surveillance and autonomous driving systems, the work offers a practical reference for follow-up research and real-world deployments, thereby raising the application value of low-light image data.

Related works

In recent years, significant advances have been made in low-light image enhancement methods based on deep learning. These methods have been shown to be capable of effectively improving the visibility and detail representation of images by learning features from large amounts of data. Q. Mu et al. addressed the issue of blurred details in extremely low-light conditions for knowledge-driven retinal image enhancement methods by improving the decomposition and restoration network, proposing a multi-level feature fusion network for low-light image enhancement. On the LOL v1 dataset, their method achieved a 13% and 12% improvement in Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) and Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), respectively, compared to the original approach7. E. Radmand et al. employed an low-light image enhancement algorithm combined with a guided filtering using a guided kernel, achieving a PSNR of 18.80 on the LOL v1 dataset, significantly outperforming existing methods. Their approach also improved SSIM and Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE), effectively balancing visibility enhancement with noise suppression8. X. Ma et al., from the perspective of spectral reflectance, integrated Retinex theory with deep learning, demonstrating superior performance in noise suppression and color restoration compared to traditional methods, thus validating the effectiveness of this approach in low-light scenarios9. G. Yadav et al. tackled backlit images by constructing a multi-light mapping through region segmentation and transfer learning, achieving values of 8.10, 7.52, and 0.58 for contrast, entropy, and SSIM, respectively. Their method demonstrated superior subjective and objective performance compared to existing solutions10.

In response to the problems of over enhancement and brightness drift in traditional Histogram Equalization (HE), researchers have proposed various improvement schemes through strategies such as dynamic parameter optimization and visual prior fusion. H. Tanaka et al. proposed a generalized HE method that constructs histograms using differential gray-level power functions, achieving efficient contrast enhancement while preserving the average brightness of the input image11. Y. Wu et al., addressing the over- and under-enhancement issues of traditional HE, constructed a texture saliency map and an attention weight map, and optimized the histogram by incorporating a narrow dynamic range prior, resulting in superior performance in both contrast improvement and subjective visual quality12. H. Yang et al. designed a dual-branch algorithm using a cycle-consistent adversarial network to balance content preservation and brightness enhancement in low-light images, outperforming mainstream algorithms in both subjective and objective metrics13. D. Samraj et al. applied a genetic algorithm to optimize HE parameters, solving the low-contrast problem in breast cancer medical images. Their method enhances contrast while preserving brightness and visual quality, thereby supporting disease detection14.

In summary, in the existing research on low-light image enhancement, deep learning methods rely on a large amount of annotated data and have high hardware requirements. Traditional HE is prone to over enhancement or amplification of noise, and fixed parameter gamma correction is difficult to adapt to changes in brightness in multi-scenes. Moreover, multi-focus overall brightness improvement has insufficient attention to local uneven lighting and multi-frame collaborative processing. To this end, the study proposes a unified brightness range for multi-frame grouping denoising and adaptive gamma correction, combined with YUV blind source separation denoising and Pearson growth curve adjustment. For uneven lighting in a single frame, dual-scale region partitioning and improved 2D gamma function dynamic adjustment are adopted to solve the problems of brightness fluctuations, noise amplification, and local overexposure.

Methods and materials

Low-light color image enhancement algorithm

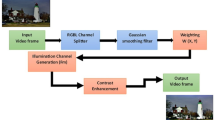

Color images obtained in low-light environments often face problems such as uneven brightness distribution, blurry detail information, and significant noise interference. Although traditional enhancement methods can improve brightness, they are prone to local overexposure or detail loss due to global adjustments, and some algorithms have limitations in computational efficiency. A multi-step collaborative optimization algorithm framework has been developed to address the aforementioned issues. Firstly, multi-frames of low-light images are continuously collected under a fixed field of view and grouped. Each group is initially denoised using the frame averaging method to obtain multi-initial denoised images15. Subsequently, adaptive gamma correction is applied to these denoised images to adjust their brightness to a stable range, providing consistent input for subsequent processing. The specific algorithm process is denoted in Fig. 1.

In Fig. 1, the algorithm performs preliminary enhancement on the image through adaptive gamma correction. Traditional gamma correction is difficult to adapt to brightness fluctuations in multi-frames of images due to fixed parameters, which affects the stability of subsequent blind source separation algorithms. Therefore, the study aims to unify the brightness of multi-frames of low-light images to a stable range by dynamically adjusting the gamma index, to solve the interference of inconsistent brightness in the preprocessing of multi-frames of low-light images on subsequent processing. The improvement method dynamically adjusts the gamma correction index \(\gamma\) to make the brightness of multi-frames of images after correction tend to be consistent. The specific calculation formula is denoted in Eq. (1)16.

In Eq. (1), \({I_{out}}\) means the output brightness value after gamma correction, and d means the scaling factor with a value of 1. B represents the result of normalizing the input brightness to the [0,1] interval, and \({B_a}\) is the median of the normalized brightness B of the input image. a is the target brightness mean, \(\gamma\) is determined by the target brightness mean a and the median \({B_a}\) of the input image, and the target brightness mean a is set based on the actual mean \(\bar {B}\) of the input image. The setting rule is shown in Eq. (2).

Equations (1) and (2) adaptively adjust the gamma index to stabilize the brightness of the input image sequence within a uniform range, thereby solving the brightness fluctuation problem caused by traditional fixed parameter gamma correction. When inputting 200 frames of low-light images, the average brightness changes after traditional gamma correction and improved gamma correction are shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2 (a) compares the brightness stability of gamma corrected images before and after improvement, while Fig. 2 (b) shows the brightness stability of the initial image.

As shown in Fig. 2, fixed parameter gamma correction cannot adapt to the brightness differences between different frames due to the use of a unified γ value. The average brightness of the corrected image fluctuates greatly, with a standard deviation of 6.546 × 103. The adaptive parameter gamma correction effectively suppresses brightness fluctuations by dynamically adjusting the γ index. The standard deviation of the brightness mean of the corrected image is only 1.385 × 103, which is about 53% lower than the original image. After initial enhancement, the image needs to be converted from the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) space to the YUV space. The U, V channels, as a chromaticity component, have a narrow range of normalized values, and the noise highly overlaps with the range and distribution of these two components. However, subsequent blind source separation algorithms have poor separation performance for components with similar distributions17. In contrast, the Y channel, as a brightness component, has a wider range of values and a significantly different distribution from noise, making it easier to denoise through blind source separation. If directly processing the RGB three channels, it is necessary to denoise each of the three components separately, which will significantly increase the computational complexity. The conversion formula under BT.601 standard is denoted in Eq. (3)18,19.

In Eq. (3), Y represents the brightness component, while U and V correspond to the blue and red chromaticity components, respectively. Afterwards, blind source separation and noise reduction are performed on the converted image. Weight adjusted second-order blind identification (WASOBI) is an algorithm used in signal processing that estimates a hybrid system by jointly diagonalizing multi-delay covariance matrices and dynamically adjusting the weights of each delay covariance matrix during the iteration process. The denoising sequence \({C_Y}(t)\) of the Y channel obtained by WASOBI is shown in Eq. (4)20.

In Eq. (4), W denotes a unitary matrix solved by nonlinear weighted least squares method, used to convert mixed observation signals into independent source signals, and its inverse operation ensures the accuracy of signal reconstruction. \({\hat {r}_Y}(t)\) is the deaveraged mixed observation matrix, and \({\bar {r}_Y}(t)\) is the mean vector, representing the average brightness component of the original observation signal. Due to the fact that the denoising image sequence output by WASOBI only contains one effective denoising image, while the rest are noisy images, and the images in this sequence are arranged in an unordered manner. To address this issue, a study was conducted using the Y channel image processed by frame averaging as a reference. The reference image and the WASOBI processed image were resized according to the scaling factor \(\eta\), \(0.1<\eta <1\). Then, the adjusted reference image was used as a control, and the SSIM index was used to compare the scaled image sequence, ultimately completing the sorting of the image sequence21. After the above operations, the contrast enhancement effect of the image is still limited. Further research is needed to improve image contrast through Adaptive Histogram Equalization (AHE)22. Due to the fact that gamma transformation is essentially a power operation, its effect on bases close to 1 is limited. The transformation curve is shown in Fig. 3. Figures 3 (a) and 3 (b) denote the curves of traditional gamma transform and dual gamma transform, respectively.

From Fig. 3, when \(\gamma < 1\) is used, the output of traditional gamma transform in high brightness areas was close to 0.9, and the brightness suppression effect was weak. However, although dual gamma transform attempted to adjust in segments, it still lacked effective control over the area where the brightness was normalized to 1. Therefore, the study adopted the Pearson growth curve to balance the brightness of the image. The Pearson growth curve and the image grayscale accumulation curve are denoted in Fig. 4. Figure 4 (a) showcases the Peel growth curve, and Fig. 4 (b) showcases the grayscale accumulation curve of normal brightness and high brightness images.

According to Fig. 4 (a), the Pearson curve includes a lag period (slow population growth rate), a logarithmic growth period (growth rate close to the maximum), and a plateau period (population size tends to stabilize). In Fig. 4 (b), under normal lighting conditions, the variation pattern of the image in the high and low brightness parts was consistent with the shape of the Pearson curve, and the number of pixels in the image showed a gentle increasing trend. Under strong light conditions, the number of pixels in the highlighted area still showed a rapid growth trend. To smooth out this upward trend and reduce the grayscale value of the region, a fitted Pearson growth curve model was used for brightness adjustment. The brightness value \(Q\left( {i,j} \right)\) of the output image is denoted in Eq. (5)23.

In Eq. (5), \(R\left( {i,j} \right)\) is the brightness of the image processed by MSRCR, \(\frac{P}{{1+\alpha {e^{ - \beta \Delta }}}}\) is the Pearson model, P, \(\alpha\), and \(\beta\) are the parameters to be fitted to the model, and \(\Delta =1 - R\left( {i,j} \right)\) is used. Then, the multi-scale Gaussian convolution method is used to obtain the highest quality image light component \(O\left( {i,j} \right)\). Then, the previously brightness adjusted image is balanced using a two-dimensional gamma function, as shown in Eq. (6)24.

In Eq. (6), \(A\left( {i,j} \right)\) is the brightness value of the corrected image, \(\gamma ^{\prime}\) is the gamma correction parameter, \({Q_m}\) is the mean of \(Q\left( {i,j} \right)\), \(\varepsilon =0.05\). After completing the above operations, the image needs to be returned to the RGB space and a linear transformation with maximum value limitation should be performed according to Eq. (7) to optimize the grayscale distribution25.

In Eq. (7), \({A_{\hbox{max} }}\) and \({A_{\hbox{min} }}\) are the mini and max values of \(A\left( {i,j} \right)\), respectively.

Image brightness equalization algorithm based on region partitioning

The algorithm proposed in the previous section for processing low-light images adopts a multi-frame processing method, and there are certain limitations in the enhancement effect of images with uneven lighting. In practical applications, images are mostly processed as single frame images, and most images have uneven lighting. A region-based image brightness equalization algorithm has been proposed to address this issue. The algorithm process is shown in Fig. 5.

As shown in Fig. 5, the algorithm mainly constructs adaptive target brightness parameters by mining local feature information of the image, and completes adaptive gamma correction operation by combining the light components of the image. Firstly, the input RGB image is transformed into the Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV) space, and then the brightness levels of the image are divided to achieve targeted enhancement. The brightness mean interval of the V-channel image is [0,1]. When the brightness mean \({I_V}\) of the V-channel is greater than the threshold \({I_T}\), the image belongs to a high brightness image. To simplify the processing flow, a dehazing algorithm is studied to convert high brightness images into brightness limited images with a brightness mean of [0,1-IT]. The acquisition of \({I_L}\) is denoted in Eq. (8)26.

In Eq. (8), \({\bar {I}_V}\) is the average brightness of the V-channel image. The division of brightness regions is a key step in achieving precise enhancement when dealing with images with uneven lighting. The study adopts a dual scale adaptive threshold binarization method to divide the brightness region. The first type of binarization calculates the neighborhood mean \({E_{w1 \times w1}}(x,y)\) of each pixel point through the mean filtering of the \(w1 \times w1\) window size, and then divides it by the corresponding brightness value \(E(x,y)\). Afterwards, it is compared with the sensitivity parameter \(\varphi\) and subjected to binarization processing. The sensitivity parameter \(\varphi\) is determined by the average brightness value, as shown in Eq. (9)27.

The calculation process of the image \({E_{s1}}\) output by the binarization operation is shown in Eq. (10).

The second type of binarization is based on edge extraction of the difference image. The neighborhood mean \({E_{w2 \times w2}}(x,y)\) is calculated through the mean filtering of \(w2 \times w2\) window size. The original image E is subtracted by \({E_{w2 \times w2}}(x,y)\) and constant H to obtain the difference image \({I_C}\), which is then binarized to output the binary image \({E_{s2}}(x,y)\), as shown in Eq. (11)28.

After fusing the images obtained from the above two operations through logic and operations, morphological denoising is performed on the fused images using dilation and erosion methods, and region boundary labeling is performed29. After completing the division of brightness regions, to achieve accurate brightness balance, it is necessary to further extract the lighting components of the image to characterize the true lighting distribution of the scene. The study selects a fast guided filter for extracting light components, and the operation process is shown in Fig. 6.

From Fig. 6, there is a linear correspondence between the filtered output u and the guided image I, as shown in Eq. (12)30.

In Eq. (12), \({p_k}\) and \({q_k}\) are linear coefficients within the window \({w_k}\). Due to the gradient relationship of \(\nabla u=p\nabla I\), Eq. (12) can preserve the edge information of the guiding image in the output image. A linear regression model is established in the window \({w_k}\) with the goal of minimizing the difference between the input and output images, as shown in Eq. (13)31.

In Eq. (13), \({v_i}\) is the input image and \(\sigma\) is the regularization parameter. By solving the minimum value problem mentioned above, the coefficients \({p_k}\) and \({q_k}\) within the window \({w_k}\) can be obtained. The study extracted corresponding grayscale images from color images using different filtering methods, and the results are denoted in Fig. 7. Figure 7 (a) is the original image, and Figs. 7 (b), 7 (c), and 7 (d) are the light maps of Gaussian filtering, bilateral filtering, and guided filtering, respectively.

From Fig. 7, the overall brightness of the light map extracted by Gaussian filtering is dim, and the edge details are clearly scattered. Although bilateral filtering preserves some of the light dark boundary edges, it excessively presents object edge details in local areas, causing deviations between the light components and the true light source distribution. The light map extracted by guided filtering has clear boundaries at the edges of the light dark transition region, and the details of each region are moderately simplified, which is more in line with the overall and local characteristics of the real light distribution. After completing the extraction of light components and region partitioning, the study aims to achieve brightness balance in images through a two-dimensional gamma function. In images with significant differences in brightness and darkness, the correction effect of traditional two-dimensional gamma functions is limited. To this end, the study proposed an improvement to the two-dimensional gamma function by integrating the target mean and light components to achieve adaptive brightness adjustment. The improved correction function is denoted in Eq. (14)32.

In Eq. (4), \({I_G}\) is the corrected image, \({\gamma _0}\) is the adaptive gamma index, \({I_u}\) is the light component extracted by guided filtering, \(W(x,y)\) is the target mean matrix, dynamically set according to the brightness characteristics of the region, as shown in Eq. (15)33.

In Eq. (15), \(\delta\) is the adjustment parameter, taken as 5 and 10 in the dark and bright areas, respectively. \({h_i}\) is the brightness characteristic of region i, \({I_z}\) is the ideal target mean, \({I_z}=0.5\). When the light component \({I_u}\) is greater than the target mean W, \({\gamma _0}> 1\), and brightness suppression is performed on high light areas. Conversely, \({\gamma _0}< 1\). Grayscale stretching is applied to low-light areas. Compared with the traditional two-dimensional gamma function, the improved method introduces the regional brightness difference feature \({h_i}\) and the adaptive adjustment parameter \(\delta\), allowing the gamma index to dynamically change according to local brightness and darkness attributes. When there is a lot of noise in the corrected image, a guided filter with a regularization parameter of 1e-4 and a filtering radius of 6 can be used to denoise it. Afterwards, \({I_G}\) is balanced using a histogram with limited contrast, as shown in Eq. (16)34.

In Eq. (16), \({r_1}\) and \({r_2}\) are weighting coefficients for \({I_s}\) and \({I_G}\), respectively. \({I_F}\) is the output image after equalization, and \({I_s}\) is the image after equalization processing. \(\omega \left( {{I_V}} \right)\) is the average brightness of the original image in the V channel. The balanced output image is integrated with the H and S channel images of the original image into HSV space and converted to RGB format to obtain the final output image.

Results

Validation of low-light color image enhancement algorithm

To assess the performance of the proposed low-light image enhancement algorithm, a set of low-light images were selected as the test objects. For this scenario, 200 frames were continuously captured and uniformly grouped, where the number of groups n ranged from 1 to 200. The experimental operating environment was a desktop computer equipped with an Intel Core i5-1135G7 2.50 GHz quad core processor and 8GB DDR4 memory. The verification related parameter settings are shown in Table 1.

The image processed by the enhancement algorithm is shown in Fig. 8. Figures 8 (a) to 8 (f) show the images for n = 2, 10, 20, 50, and 200, respectively. Figures 8 (g) and 8 (h) show the images after gamma enhancement and HE enhancement, respectively.

In Fig. 8, the overall brightness and contrast of the original image were at a low level, making it difficult for the human eye to recognize specific details. After being processed by the proposed enhancement algorithm, the brightness and contrast of the image were significantly improved, the details were presented more clearly, and there was no local overexposure phenomenon. In terms of color expression, the enhancement results were basically consistent with the effect under normal lighting conditions. When the number of groups was 200, the matching degree between the image and the real scene color was higher, indicating that the algorithm can effectively restore the detailed features and color information of the original scene. From Fig. 8 (g) and Fig. 8 (h), the enhancement results of the two methods had significant noise issues; The enhanced results of the research method had cleaner images and better performance in noise suppression. The performance of the algorithm in different low-light images varied with the number of groups, as shown in Fig. 9. Figures 9 (a) and 9 (b) show the variation of the average brightness and running time of the enhanced image with the number of groups, respectively.

According to Fig. 9 (a), as the amount of groups n gradually increased from 1 to 100, the average brightness of the image showed a stable upward trend, indicating that with the rising of the amount of groups, the overall brightness of the image has been significantly improved. As n continued to increase from 100, the growth rate of the average brightness began to slow down and gradually stabilized, indicating that increasing the number of groups after reaching a certain scale has limited effect on improving brightness. As shown in Fig. 9 (b), with the increase of the number of groups, the running time of the algorithm gradually increased. When the scaling factor \(\eta =1\) was used, the processing time of the algorithm for each image was greater than 20 s, while when the scaling factor \(\eta =0.1\) was used, the processing efficiency of the algorithm for each image was significantly improved, and the processing time was less than 10 s. Therefore, using the method of reducing the image size for quality evaluation ranking can effectively improve processing efficiency.

To test the superiority of the proposed method over other image processing methods, this study conducted comparative tests on other typical image enhancement algorithms, including Multi-Scale Retinex with Color Restoration (MSRCR), Low-Light Image Enhancement (LIME), and relevant research in the latest literature7,8. The grayscale histograms obtained by processing low-light images using various methods are denoted in Fig. 10. Figure 10 (a) showcases the grayscale histogram after MSRCR and LIME processing, and Fig. 10 (b) shows the grayscale histogram after the latest research processing.

As shown in Fig. 10 (a), the histogram of the original image exhibited typical low-light characteristics, with pixel heights concentrated in the extremely low grayscale range of 0–50. After processing with the LIME algorithm, the peaks in the low gray area were significantly weakened, and the pixel distribution shifted significantly to the right, forming a relatively flat platform in the range of 50–150. At the same time, there was a slight uplift in the bright area of 200–250. This change confirmed that LIME effectively improved the brightness of dark areas and expanded the dynamic range, but the peak at 250 grayscale indicated overexposure in some high light areas. Although the histogram of MSRCR also achieved a right shift in dark area pixels, the overall distribution was more concentrated, and the dynamic range expansion effect was not as significant as LIME. As shown in Fig. 10 (b), both literature7,8 suffered from overexposure issues. The research method has better control in bright areas, with lower pixel counts at 250 Gy levels, indicating that while preserving the enhancement effect in dark areas, overexposure is more effectively suppressed. The performance evaluation index parameter values of each method are denoted in Table 2.

According to Table 2, in terms of brightness mean, the study was at a relatively high level in Image 1 (57.14), Image 2 (78.26), and Image 3 (80.02), with Image 3 having the highest 80.02 among all methods, indicating that its brightness improvement is both sufficient and avoids overexposure. Information entropy reflects image detail richness. The study was at the top with values ranging from 7.05 to 8.19, only image 2 was slightly lower than the 8.21 of the literature8, with better detail retention ability. BRISQUE is a key measure of image quality. The study verified its superiority in noise suppression and overall quality with the lowest values of 45.21 (Image 1), 44.09 (Image 2), and 24.95 (Image 3). The SSIM studied was 0.80–0.87, with only Image 1 slightly lower than the 0.81 in reference7, and the structure remained closer to the original image. In terms of running time, the study demonstrated efficient processing capability with a minimum time consumption of 2.47 s to 2.55 s. Based on core dimensions such as brightness, quality, and efficiency, the research was still the optimal solution.

The computational complexity of the algorithm proposed in the research mainly stems from multi-frame collaborative processing. The time complexity of multi-frame average denoising and adaptive gamma correction is both linear O(n×w×h), where n is the number of frames and w and h are the width and height of the image, and the processing efficiency is relatively high. The algorithm complexity is mainly concentrated in the WASOBI blind source separation step, approximately O(m³) (m is the signal dimension). The research reduced the computational load through image grouping processing and downsampling strategies, shortening the processing time from over 20 s to 2.47 s to 2.55 s. In terms of scalability, the algorithm adapt to different computing power platforms by adjusting the number of packets n and the downsampling coefficient k: on mobile devices, smaller n and k values can be used to achieve real-time processing, while on the server side, larger n and full resolution can be used to obtain the optimal enhancement effect.

To further validate the algorithm’s real-time performance on mobile devices, it conducted tests on an ARM Cortex-A76 processor-equipped Android platform. When parameters n = 5 and k = 0.3 were set, the average processing time for a single 640 × 480 image frame reached 48.2ms, meeting the 30fps real-time processing requirement. Additionally, by leveraging OpenCL acceleration for the guidance filtering and gamma correction steps, the processing time was reduced to under 35ms, demonstrating the algorithm’s strong potential for mobile deployment. This design enables the algorithm to adapt to various deployment environments ranging from embedded devices to cloud servers.

Verification of image brightness balance algorithm

To test the effect of the region-based image brightness equalization algorithm proposed in the study, images with uneven lighting were selected as the test objects. Typical Brightness Preserving Dynamic Histogram Equalization (BPDHE), Naturality Preserved Enhancement (NPE), and the latest literature11,12 were compared and tested. The experimental operating environment is the same as Sect. Low-light color image enhancement algorithm. The images processed by different algorithms are dented in Fig. 11. Figure 11 (a) shows the original image, and Figs. 11 (b) to 11 (f) are the images processed by BPDHE, NPE, literature11, literature12, and research method, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 11, the BPDHE algorithm did not significantly improve the brightness of the image, and the overall details of the image were still difficult to identify. The NPE algorithm could significantly improve brightness, but there were obvious contours and overly sharpened details. Literature11 enhanced the details of dark areas, but generated more noise. Literature12 could effectively improve brightness, but excessive brightness enhancement in bright areas led to significant differences in brightness across the entire image. The algorithm proposed in the study outperformed other methods in terms of brightness, contrast, color, and detail. The details in the dark area, such as the outline of a book, were relatively clear, and the overall image lighting was uniform without excessive enhancement. The image colors were natural, noise was effectively suppressed, and the visual effect was more in line with the subjective perception of the human eye. To verify the processing effect of brightness equalization algorithm on high brightness images, various methods were studied for processing high brightness images with uneven lighting, and the findings are denoted in Fig. 12. Figure 12 (a) shows the original image, and Figs. 12 (b) to 12 (f) are the images processed by BPDHE, NPE, literature11, literature12, and research method, respectively.

From Fig. 12, the algorithm proposed in the study had a significantly different image processing effect compared to the other five comparison algorithms. A comparison of the original image and the image processed by the research method revealed that the former was significantly brighter. In contrast, the enhancement effect of the other five comparison algorithms was largely consistent with the original image. For instance, NPE and literature12 have been shown to enhance image brightness. It is demonstrated that the research method remains viable for the processing of high-brightness images. The objective evaluation results of different methods for different images are denoted in Table 3.

According to Table 3, in terms of average gradient, the study achieved 25.32, 26.83, and 27.12 in the three images respectively, all higher than the comparison method, indicating that its detail preservation is richer. The BRIQU studied verified the superiority of noise suppression and overall quality with the lowest values of 32.18, 30.52, and 28.75. In terms of Visual Information Fidelity (VIF) and Edge Measure Evaluation (EME), the study showed the highest values of 0.89–0.93 and 12.45–14.15 respectively, demonstrating its advantages in detail fidelity and edge clarity. The research method was the optimal solution based on comprehensive dimensions such as details, quality, and edges. To verify the superiority of the brightness equalization algorithm in terms of time complexity, a comparative analysis was conducted on the time required for processing images of different sizes using various methods. The findings are denoted in Fig. 13. Figure 13 (a) and Fig. 13 (b) respectively show the comparison of processing time for non-uniform brightness images and high brightness non-uniform images using various methods.

As shown in Fig. 13 (a), the processing time of each method for images with uneven brightness increased at an accelerated rate with the increase of image size. Literature11 showed the fastest growth rate (for example, when the scaling ratio was 0.1, the corresponding processing time was 8.42ms, and increased to 208.41ms at 1.0), followed by NPE, BPDHE, and literature12. The research method had the slowest growth rate (the processing time was 5.18ms at a scaling ratio of 0.1, and only 85.06ms at 1.0). According to Fig. 13 (b), the processing time trend of high brightness non-uniform images was consistent with Fig. 13 (a), and the processing time of each method was slightly higher than that of Fig. 13 (a). The research method still maintained the slowest growth rate, with a processing time of 85.06 ms at a scaling ratio of 1, demonstrating its superiority in image processing efficiency.

To evaluate the algorithm’s brightness balance performance under dynamic lighting conditions, experiments utilized two datasets: the publicly available LOL-IR Dynamic Lighting subset (30 images across three scenarios including moving light sources, with resolution 1280 × 720) and a self-developed real-scenario dataset (40 images featuring mall spotlights and similar environments, with resolution 2560 × 1440). The evaluation criteria introduced two new metrics: Local Brightness Deviation (ΔL) and Edge Transition Smoothness (ETS), specifically designed to assess the algorithm’s local balance and edge preservation capabilities in dynamic lighting environments. Comparative performance analysis of all algorithms is presented in Table 4.

As shown in Table 4, the proposed method demonstrated superior performance across three dynamic lighting scenarios: moving light sources, transient occlusions, and sudden bright light events. In terms of local brightness balance, its deviation (ΔL = 9.87–13.56) was significantly lower than BPDHE (28.63–35.87) and NPE (22.45–28.92), while also outperforming literature37 (17.52–21.67) and38 (16.18–20.32). This advantage stems from the dual-scale region partitioning and dynamic adjustment of the improved two-dimensional gamma function. For detail and edge representation, the method showed notable strengths in average gradient (25.76–26.98), visual information fidelity (VIF = 0.88–0.91), edge strength index (EME = 12.47–13.56), and edge transition smoothness (ETS = 0.85–0.89). Guided filtering and constrained histogram equalization ensure detailed edge preservation. In terms of real-time performance, the processing time (85.06 ~ 89.65ms) was shorter than those reported in37(102.58 ~ 108.65ms] and38(98.76 ~ 104.23ms], meeting practical application requirements. While showing minor limitations in extreme bright light scenarios, the overall advantages remained significant.

For the image luminance equalization algorithm based on region division (single-frame processing), its computational complexity mainly comes from image segmentation and filtering operations. The time complexity of steps such as HSV conversion, dual-scale region division, guided filtering and improved two-dimensional gamma correction was all linear O(w×h), and the algorithm efficiency was relatively high. The full-size image processing only required 85.06ms. In terms of scalability, the algorithm demonstrated excellent adaptability: Firstly, its linear time complexity enabled it to efficiently process high-resolution images (including 4 K/8K); Secondly, the algorithm could effectively handle various uneven lighting situations (such as local shadows, backlighting, etc.) without the need for retraining or adjusting the model. Finally, the parameter adaptive mechanism (such as the sensitivity parameter k being automatically set based on the mean image brightness) ensured the stability of the algorithm in different scenarios.

The algorithm was tested on mobile devices, achieving processing speeds of 126ms for 1080p images and approximately 420ms for 4 K images. Through optimization using the NEON instruction set, the latency could be reduced to below 300ms, demonstrating real-time processing capabilities for high-end mobile devices. Additionally, the algorithm supported block processing and thread parallelism, effectively leveraging multi-core CPUs and GPU acceleration. This made it suitable for edge computing scenarios such as smart surveillance cameras and vehicle-mounted systems, enabling broad application across platforms ranging from mobile terminals to high-performance servers.

Conclusion

To improve the problem of dim brightness and uneven local lighting in low-light color images, and thus enhance image quality to meet practical application needs, this study investigated the use of multi-frame grouping denoising and adaptive gamma correction for brightness range, combined with YUV spatial blind source separation denoising and Pearson growth curve adjustment for brightness. To address uneven light in a single frame, dual-scale adaptive gamma correction were adopted to suppress overexposure and preserve details. The results showed that the improved algorithm achieved a brightness mean of 57.14–80.02, information entropy of 7.05–8.19, BRISQUE of 24.95–45.21, and SSIM of 0.80–0.87 in low-light image enhancement, all of which were superior to methods such as MSRCR and LIME, with processing times of only 2.47–2.55 s. In images with uneven lighting, the average gradient was 25.32–27.12, VIF was 0.89–0.93, and EME was 12.45–14.15. Moreover, the research method had the highest image processing efficiency and the best overall performance. The multi-step collaborative optimization algorithm proposed in the study effectively solved the problems of brightness fluctuations, noise amplification, and local overexposure in low-light images, providing technical support for low-light image applications in fields such as security monitoring and autonomous driving. The current research has not explored dynamic lighting scenarios. In the future, dynamic lighting testing can be expanded, algorithm complexity can be optimized to adapt to mobile devices, and multi-modal data can be combined to enhance the enhancement effect.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yao, J., Wang, J., Wang, Y. & Hong, F. A tourist flow monitoring and management system for scenic areas using image Recognition, trait. Signal 42 (2), 963–973. https://doi.org/10.18280/ts.420230 (2025).

Qin, J., Jiang, Z. & Lei, X. Low illumination image object detection method based on ICFIE-YOLO. Acta Electron. Sin. 53 (2), 514–526. https://doi.org/10.12263/DZXB.20240648 (2025).

Bataineh, B. Brightness and contrast enhancement method for color images via pairing adaptive gamma correction and histogram equalization. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 14 (3), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2023.0140316 (2023).

Li, X., Liu, M. & Ling, Q. Pixel-Wise Gamma Correction Mapping for Low-Light Image Enhancement, IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol., 34 (2), 681–694, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3286802. (2024).

Purohit, J. & Dave, R. Leveraging Deep Learning Techniques to Obtain Efficacious Segmentation Results, Archives Adv. Eng. Sci., 1 (1), 11–26, https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewAAES32021220.July, (2023).

Martin, A. & Newman, J. Significance of image brightness levels for PRNU camera identification. J. Forensic Sci. 70 (1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.15673 (2025).

Mu, Q., Ma, Y., Li, H. & Li, Z. Low-Light Image Enhancement Network of Multi-Level Feature Fusion, Comput. Eng. Appl., 61 (10), 238–246 https://doi.org/10.3778/j.issn.1002-8331.2401-0249. (2025).

Radmand, E., Saberi, E., Sorkhi, A. G. & Pirgazi, J. Low-light image enhancement using the illumination boost algorithm along with the SKWGIF method. Multimed Tools Appl. 84 (17), 18651–18685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-19720-9 (2025).

Ma, X., Cao, Q., Bai, C., Wang, X. & Zhang, D. Research on Low Illumination Image Enhancement Method Based on Spectral Reflectance, Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal., 44 (3), 610–616 https://doi.org/10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2024)03-0610-07. (2024).

Yadav, G. & Yadav, D. K. Multi-Illumination Mapping-Based Fusion Method for Low-Light Area’s Visibility and Backlit Image Enhancement, Arab. J. Sci. Eng., 49 (3), 3095–3108 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-023-07923-5. (2024).

Tanaka, H. & Taguchi, A. Brightness preserving generalized histogram equalization with high contrast enhancement ability. IEICE Trans. Fundam Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. E106A (3), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1587/transfun.2022SMP0002 (2023).

Wu, Y., Dai, S. & Ma, Z. Advanced Histogram Equalization Based on a Hybrid Saliency Map and Novel Visual Prior, Mach. Intell. Res., 21 (6), 1178–1191 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11633-023-1448-2. (2024).

Yang, H., Li, X., Zhang, H. & Meng, Y. Dual-Branch Structure Low-Light Image Enhancement Algorithm Combined with Brightness Constraint, Comput. Eng. Appl., 61 (8), 250–259 https://doi.org/10.3778/j.issn.1002-8331.2312-0264. (2025).

Samraj, D., Ramasamy, K. & Krishnasamy, B. Enhancement and diagnosis of breast cancer in mammography images using histogram equalization and genetic Algorithm, multidimens. Syst. Signal. Process. 34 (3), 681–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11045-023-00880-0 (2023).

Palani, V., Alharbi, M., Alshahrani, M. & Rajendran, S. Pixel Optimization Using Iterative Pixel Compression Algorithm for Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor Image Sensors, Trait Signal., 40 (2), 693–699 https://doi.org/10.18280/ts.400228. (2023).

Yamaguchi, M. et al. Hue-preserving image enhancement for the elderly based on wavelength-dependent gamma correction. Opt. Rev. 32 (1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10043-024-00932-1 (2025).

He, Z., Lin, M., Luo, X. & Xu, Z. Structure-preserved self-attention for fusion image information in multiple color spaces. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 36 (7), 13021–13035. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3490800 (2025).

Sebastian, J., King, G. R. & Gnana, G. A novel MRI and PET image fusion in the NSST domain using YUV color space based on convolutional neural Networks, Wirel. Pers. Commun. 131 (3), 2295–2309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11277-023-10542-w (2023).

Babalola, F. O., Toygar, O. & Bitirim, Y. Boosting hand vein recognition performance with the fusion of different color spaces in deep learning architectures. Signal. Image Video Process. 17 (8), 4375–4383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11760-023-02671-3 (2023).

Bekhtaoui, Z., Abed-Meraim, K., Meche, A. & Thameri, M. A new robust adaptive algorithm for second-order blind source separation. ENP Eng. Sci. J. 2 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.47852/ENPESJ020121 (2022).

Yang, J., Feng, X., Teng, L., Liu, H. & Zhang, H. A lossless compression and encryption scheme for sequence images based on 2D-CTCCM, MDFSM and STP. Nonlinear Dyn. 112 (8), 6715–6741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-024-09354-9 (2024).

Mondal, K., Rabidas, R. & Dasgupta, R. Single Image Haze Removal Using Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization Based Multiscale Fusion Technique, Multimed Tools Appl., 83 (5), 15413–15438 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-021-11890-0. (2024).

Chweya, C. M. et al. Predictors of hypoglossal nerve stimulator usage: A growth curve analysis study. Otolaryngol. –Head Neck Surg. 172(6), 2116–2123. https://doi.org/10.1002/ohn.1219 (2025).

Chen, L. & Chen, L. Method for correcting low-illumination images based on adaptive two-dimensional gamma function. Acad. J. Eng. Technol. Sci., 5 (5), 34–40, 2022.

Lang, Y. et al. Effective enhancement method of low-light-level images based on the guided filter and multi-scale fusion. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A. 40 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.468876 (2023).

Choi, S. et al. Optimizing 2D image quality in cartoongan: A novel approach using enhanced pixel integration. Comput. Mater. Continua. 83 (4), 335–355. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.061243 (2025).

Liu, F. An overview of image enhancement dehazing algorithms. Appl. Comput. Eng. 4 (32523), 738–742. https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-2721/4/2023411 (2023).

Cuenca, M. F. F., Malikov, A. K., Kim, J., Kim, Y. H. & Cho, Y. A novel method of ultrasonic tomographic imaging of defects in the coating layer by image fusion and binarization techniques. J. Vis. 27 (6), 1077–1088. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12650-024-01007-8 (2024).

Xue, S., Zhang, J., Li, B. & Li, X. Mathematical Morphology Denoising and Interference Recognition Method for DC Protection, Dianli Xitong Baohu yu Kongzhi/Power Syst. Prot. Control, 52 (13), 136–148, DOI: https://doi.org/10.19783/j.cnki.pspc.231197. (2024).

Li, X., Chen, H., Li, Y. & Peng, Y. Multi-Focus Image Fusion Via Adaptive Fractional Differential and Guided Filtering, Multimed Tools Appl., 83 (11), 32923–32943 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-16785-w. (2024).

Su, Z., Wang, W. & Zhang, W. Regularized denoising latent subspace based linear regression for image classification. Pattern Anal. Appl. 26 (3), 1027–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10044-023-01149-9 (2023).

Zhou, H., Shu, D., Wu, C., Wang, Q. & Wang, Q. Image illumination adaptive correction algorithm based on a combined model of bottom-hat and improved gamma transformation, Arab. J. Sci. Eng., 48 (3), 3947–3960 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-022-07368-2. (2023).

Ding, S. et al. FIAFusion: A feedback-based illumination-adaptive infrared and visible image fusion method. IEEE Sens. J. 25 (4), 7667–7680. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2025.3525700 (2025).

Kim, S., You, J. & Efficient LUT Design Methodologies of Transformation Between RGB and HSV for HSV Based Image Enhancements, J. Electr. Eng. Technol., 19 (7), 4551–4563 https://doi.org/10.1007/s42835-024-01859-y. (2024).

Yi, X., Xu, H., Zhang, H., Tang, L. & Ma, J. Diff-Retinex++: Retinex-driven reinforced diffusion model for low-light image enhancement. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 47 (8), 6823–6841. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2025.3563612 (2025).

Liu, M., Cui, Y., Ren, W., Zhou, J. & Knoll, A. C. LIEDNet: A lightweight network for low-light enhancement and deblurring. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 35 (7), 6602–6615. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSVT.2025.3541429 (2025).

Hemamalini, S., Kumar, V. D. A., Ramachandran, V. & Robin, R. Retinal image enhancement through hyperparameter selection using RSO for CLAHE to classify diabetic retinopathy. Traitement Du Signal. 41 (4), 2003–2012. https://doi.org/10.18280/ts.410429 (2024).

Singh, P. & Bhandari, A. K. Laplacian and Gaussian pyramid based multiscale fusion for nighttime image enhancement. Multimed Tools Appl. 84 (15), 15527–15551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-19594-x (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H.L. processed the numerical attribute linear programming of communication big data, and the mutual information feature quantity of communication big data numerical attribute was extracted by the cloud extended distributed feature fitting method. H.H.L. combined with fuzzy C-means clustering and linear regression analysis, the statistical analysis of big data numerical attribute feature information was carried out, and the associated attribute sample set of communication big data numerical attribute cloud grid distribution was constructed. H.H.L. did the experiments, recorded data, and created manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H. Low-light color image equalization based on adaptive brightness adjustment. Sci Rep 16, 1644 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31156-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31156-1