Abstract

Seismic safety evaluation for loess ground is often tailored to local conditions, yet the influence of regional soil variability on dynamic parameters is seldom rationally addressed. This study investigated the correlation between clay activity, a synthetic physical index characterizing soil variability, and dynamic properties of intact loess, with microstructural and water-retention evidence derived from dynamic triaxial tests, water-retention tests, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. Results show that the backbone curve rises with lower clay activity, corresponding to higher dynamic shear modulus and lower damping ratio. The Hardin-Drnevich model was modified by incorporating a power relationship between reference strain and clay activity. Quantified microstructural indexes indicate that the closer the particle morphology approaches sphericity, the smoother the pore edges, and the more uniform the pore distribution, the higher the initial dynamic shear modulus Gd0 and maximum damping ratio λmax, corresponding to higher clay activity. The above microstructural morphology, rather than matric suction, exerts far greater influence on Gd0, while λmax is positively linked to matric suction or negatively to clay activity. The above preliminary results demonstrate the correlation between clay activity and dynamic behavior of intact loess and hold potential significance for seismic safety assessment of loess grounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intensive seismic zones are distributed in loess areas of northwest China1, where over 70% of urban and rural areas are classified as fortified zones above degree VII2. Seismic hazards, including subsidence, landslides, and liquefaction, present major challenges in engineering design3,4,5. In current seismic design practices for loess engineering, beyond considerations of geomorphology and sedimentary chronology, dynamic tests on field-collected loess samples are often required to obtain key design parameters such as dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio6,7,8,9,10. For Lifeline projects such as High-speed railways and long-distance water transfer projects that cover extensive loess areas, risks will arise if the measured dynamic parameters or their relationship to any single physical index, like water content or dry density, are directly applied to the seismic safety evaluation without exploring the dependence of these parameters on soil particle composition, plasticity index, and microstructure.

The dynamic behavior of loess is controlled by diverse factors, as widely evidenced by field and laboratory tests. The dynamic triaxial test provides more relevant evidence due to its versatile stress states and wider strain range11,12,13. Valuable insights have been available on the responses of dynamic stress-strain, dynamic modulus, and damping ratio of loess to environmental factors (freeze-thaw, dry-wet cycles)14,15,16,17 and loading modes (wave form, frequency, amplitude, and cycles)18,19,20. Soil microstructural changes constituted a primary cause for the above observations21. Particle composition, especially the clay content22, results in variability in loess dynamics across different regions23,24,25,26,27. Upon the rise in clay content in loess, the dynamic shear modulus first declined and then rose while the damping ratio varied conversely28, and higher peak ground acceleration was required to trigger liquefaction29. Evidently, any straightforward correlation between a single physical index and dynamic parameters is inadequate for seismic evaluation of loess ground. Even metrics that characterize the fundamental attributes of clayey soils, such as clay content or plasticity index, fail to independently capture regional loess variability, let al.one engineering control indexes like water content or dry density. The synthetic index, such as clay activity that links the consistency index and particle composition of the soil, will hold prospective importance to comparative evaluation of engineering properties of loess in diverse regions30,31. Clay activity is defined as the ratio of plasticity index to clay content, where clay content contributes to soil microstructure morphology while plasticity index is highly correlated with water-retention capacity32. It would be necessary to explore the correlation between clay activity and dynamic behavior of loess by leveraging microstructure and water-retention properties as the bridge.

Empirical models were extensively established to characterize the dynamic behavior of clayey soils, such as the dynamic shear modulus decay model that integrated plasticity index, overconsolidation ratio, and cyclic shear strain33, the initial shear stress-based model for the cyclic response of sludge soils34, and the hyperbolic model for the damping ratio of thawed saturated clay35. The classic Hardin-Drnevich model is now extensively applied in both theory and engineering practice due to its simple form, explicit physical significance, and applicability to diverse soil types36,37. This model was also extended to loess soils to cover the effects of cumulative residual strain38 and structural parameter39. In addition, impressive elasto-plastic models were constructed to describe the boundary behavior of the elastic-perfectly plastic response of soils40 and cyclic responses and anisotropy of natural and remolded clays41. The above studies promoted the development of dynamic constitutive models for clayey soils and provided important approaches for solving related engineering problems. However, since most of the above models apply to specific regions or soil types, theoretical extensions often require recalibration of model parameters. Therefore, soil texture variability should be included in modeling to facilitate the seismic evaluation of loess ground.

In this study, consolidated undrained dynamic triaxial tests, SEM tests, and water retention tests were carried out on intact loess from five sampling sites around the seismic zone in the Weihe Basin, China. Effects of clay activity on the dynamic stress-strain curve, dynamic shear modulus, and damping ratio of intact loess were evaluated by considering soil microstructure and matric suction. The Hardin-Drnevich model was extended to include the effect of clay activity and was further verified.

Materials and methods

Test material

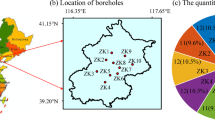

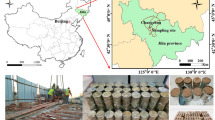

The Weihe Basin, one of the major loess areas in China, extends from Baoji in the west to Tongguan in the east. The northern margin is the Ordos Plate, while the southern margin is the Qinling Orogenic Belt. To the west, it connects with the arc-shaped faults of the southwestern edge of the Ordos Plate, and to the east, it adjoins the Shanxi Graben Belt. Active faults are well developed within the basin, accompanied by intense seismic activity. Five sampling sites, Baoji (BJ), Yangling (YL), Xianyang (XY), Xi’an (XA), and Weinan (WN), are evenly distributed from west to east around active faults, where historical earthquakes of Ms ≥ 4 occurred in adjacent areas (Fig. 1). Geomorphologic units at the sampling sites belong to the secondary terrace of the Weihe River. The Late Pleistocene (Q3) Loess that manifests remarkable seismic subsidence was sampled at a depth range of 5.0–7.0 m, within the buried depth at each site: 4.6–11.0 m (BJ), 3.1–13.1 m (YL), 1.2–11.0 m (XY), 2.6–8.5 m (XA), 3.5–21.0 m (WN). Loess particles in China vary from coarse to fine from northwest to southeast, with a rise in dynamic elastic modulus11, which is also one of the rationales for selecting sampling sites in this study.

Typical faults, historical earthquakes and sampling sites in Weihe basin. The locations of historical earthquakes and typical faults were sourced from43.

The basic physical indexes of loess were measured following the Standard for geotechnical testing method GB/T 50,123 − 201942, as listed in Table 1. The natural dry density of loess was derived from the mass of the field-collected sample with cutting ring (50.46 mm in diameter, 50 mm in height) and the natural water content determined by oven-drying at 105℃. The specific gravity of loess was obtained using the pycnometer method. The particle grading curve of loess was measured by the sieve method and the Bettersize2000 Laser Particle Size Analyzer. Both the plastic and liquid limits of loess were measured by the fall-cone method. The specific surface area was determined by the ASAP 2020 Plus Surface Area and Porosity Analyzer. The solid composition of loess was detected by a TAS-990 Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Fig. 2b). The soluble ion concentrations of loess were measured by the IC6200 ion chromatography (Anhui Wanyi Science and Technology Co., Ltd.) and the titration method.

(a) loess classification based on the plasticity chart of the Unified Soil Classification System45; (b) main solid components of loess.

The clay activity of loess was not directly calculated from the ratio of plasticity index to clay fraction (< 2 μm)30, but using 5 μm, the lower limit of particle size achievable by mechanically crushing44, whose rationality was verified by statistics of clay activity data of Xi’an loess4. From the plasticity chart of the Unified Soil Classification System45 in Fig. 2a, the loess was classified as lean clay (CL). The loess was dominated by silt, with its mass percentage declining from west to east, and the clay activity decreased from 0.82 to 0.48. The soluble ion contents of loess in Table 2 indicate the dominant roles of HCO3− in anions and Na+ and K+ in cations.

Three groups of intact loess samples were prepared: cylindrical samples for dynamic triaxial tests (39.1 mm in diameter and 80.0 mm in height), cylindrical samples for water retention tests (61.8 mm in diameter and 20.0 mm in height), and cubic samples for SEM tests (1.0 cm in side length). Samples were cut from field-collected soil blocks, with the sliced soil for water content measurement, and dry density converted from sample mass and water content. Dry density is indeed essential for soil dynamics and water-retention behavior12,22, whereas this study aimed to explore the correlation between clay activity and dynamic behavior of loess. Therefore, only samples with a dry density of 1.60 ± 0.03 g/cm³ were selected. The water contents of samples for dynamic triaxial tests were adjusted to 16%, 18% and 20% by air-drying or wetting by moist filter paper, while those for water retention tests were controlled at 6%, 8%, 11%, 13%, 16%, 18%, 20%, 22%, 24%, 25% respectively. Oven-dried samples were used in SEM tests.

Test method

Dynamic triaxial tests

The STD-20 electro-hydraulic servo soil triaxial testing machine, manufactured by Xi’an Letry Materials Testing Technology Co., Ltd., was utilized in consolidated undrained dynamic triaxial tests considering the common strain range of seismic subsidence (10− 3−10− 1)11. The technical parameters are: 0.1–20 Hz in vibration frequency, 0–20 kN in vibration load, 0–1 MPa in confining pressure, and 0.01–5 mm/min in axial deformation. Dynamic stress and strain were live captured by the DSP Trier 6202 multi-channel control system. In order to minimize the disturbance of room temperature, the pressure chamber was improved into two layers (Fig. 3), between which the coolant (ethanol) was circulated and connected to a thermostatic cold bath to control the temperature of the internal pressure chamber. The external pressure chamber was wrapped with insulation material. Besides, air conditioning was used for room temperature control. The maximum temperature fluctuation of the water in the internal pressure chamber was below 1.0 °C, while that of the room temperature was below 3.0 °C.

Before dynamic loading, the consolidation stress ratio was set at Kc = σ1c/σ3c = 1.0 to restore the static stress state of the intact loess, with axial and confining pressures (σ1c and σ3c) respectively set at 100, 200, and 300 kPa. The volume change of the unsaturated sample was converted from the stroke variation of the testing machine actuator, following the Standard for geotechnical testing method GB/T 50123 − 201942, and a volume decrement of less than 0.05 cm³ over two consecutive hours was adopted as the consolidation stability criterion. The volumetric strain of intact loess samples during consolidation, as indicated by test data, remained below 0.5% under considered confining pressures, e.g., 0.18% to 0.42% for the loess from Baoji, suggesting a minor increment in sample dry density.

An equivalent sine wave of 1 Hz was then adopted to simulate the random waveform of an earthquake. To acquire the dynamic modulus and damping ratio under different load levels, the step load was initiated at 5 N, with each subsequent load increment of 5 N applied and vibrated five times per level until sample failure. When the deformation from the applied load level exceeded twice that from the preceding, the sample was deemed to fail. All of the above test methods were performed following the recommended procedures42. Since the consolidated undrained model was employed, the shear strain of soil γ was calculated from the axial strain εa and the Poisson’s ratio v = 0.5, i.e., γ = εa(1 + v), while the volumetric strain was regarded as zero12.

The backbone curve was obtained from the dynamic shear stress and strain at the apex of the hysteresis loop in each loading cycle (Fig. 4). The initial dynamic shear modulus Gd0 was determined from the slope of the tangent to the stress-strain curve during initial loading while the dynamic shear modulus Gd for each cycle from the ratio of dynamic shear stress τd to dynamic shear strain γd. The damping ratio for each cycle was derived from the area of the hysteresis loop and the dynamic shear stress and strain amplitudes at the hysteresis loop apex (Fig. 4).

Water retention tests

The filter paper method was employed to measure the water retention curve of intact loess. The double-ring No. 203 quantitative slow filter papers were oven-dried at 105 °C before testing. One piece of test filter paper (55 mm in diameter) was sandwiched between two pieces of protective filter paper (60 mm in diameter) to form a group, which was then positioned between two samples with the gap sealed with tape, i.e., the contact method. Samples wrapped with plastic films were enclosed in a sealed container and left in a thermostat (25 ± 1 °C) for 10 days for suction equilibration between the filter paper and samples4. The test filter paper was then weighed by an electronic balance (0.0001 g) to obtain its wet mass, and after oven-drying to obtain its dry mass, from which the equilibrium water content of the filter paper was calculated. Soil matric suction was converted from the calibration model below4.

where, ψm is the matric suction of soil (kPa); wfe is the equilibrium water content of filter paper (%). Three samples were tested for each water content level, with the mean of wfe converted to the matric suction.

SEM tests

Soil microstructure was observed by the Phenom Pharos G2 Desktop FEG-SEM, with a resolution of ≤ 1.5 nm and a magnification of up to 350,000 times. The cubic sample, before scanning, was broken to obtain a fresh surface and polished into a circular disk (10 mm in diameter, 2 mm in thickness). The sample was fixed on a specialized circular metal base using conductive glue and gold-sprayed to enhance its conductivity before vacuum treatment in the SEM chamber. A representative range of the sample was observed at a magnification of 200 times. SEM images were then captured at a magnification of 1,000 times. For each sampling site, three samples were selected for SEM testing.

SEM image processing by the Pores (Particles) and Cracks Analysis System (PCAS) requires setting three preferable parameters: grey scale threshold, pore throat closure radius, and minimum pore area, which respectively correspond to binarization, pore segmentation, and noise elimination46. Detailed SEM images are more or less distorted with noise signals and should be restored and enhanced47. Grey scale threshold was selected by performing three threshold segmentations at different periods, with the mean taken when the variance was below 2. Binarized and vector images of intact loess were simultaneously obtained. Statistical indexes such as shape coefficient ff, fractal dimension Df, pore porosity distribution fractal dimension Dc, area probability distribution index ba, and probability entropy Hm were further derived46, where ff characterizes pore complexity (mainly roundness and rough edges), Df reflects the self-similarity of pore contour in natural state with a range of 1–2, Dc quantifies the variance of soil pore size distribution, ba describes the response of pore number to the change of pore area, Hm indicates the directionality of the pore arrangement with a range of 0–1.

Results and analysis

Dynamic behavior of intact loess

Effect of clay activity on dynamic responses of intact loess

The backbone curves of intact loess samples all exhibited a strain-hardening trend (Fig. 5a). Water content and confining pressure both induced variances in the morphology of backbone curves. Samples consolidated to form a denser structure at higher confining pressures, manifested a prolonged initial loading stage. Water sensitivity of intact loess was seen in the rise in dynamic shear strain upon an equivalent dynamic shear stress increment. The sample with a higher water content first failed at lower confining pressures, with lower dynamic shear strain and peak dynamic shear stress. Against the strain hardening pattern of the backbone curve, both the dynamic shear modulus Gd (Fig. 5b) and its ratio to the initial dynamic shear modulus Gd0 (Fig. 5c) decayed with dynamic shear strain. The higher the confining pressure or the lower the water content, the greater the Gd and Gd/Gd0. In Fig. 5d, along with the dynamic shear strain, the damping ratio rose markedly upon initial loading, followed by a gentle increment until sample failure. Comparisons of the curves at w = 18%, σ3c = 100 kPa, w = 20%, σ3c = 100 kPa, and w = 18%, σ3c = 300 kPa indicate that the damping ratio responded more robustly to the rise in water content. Viscous damping of pore water, as one of the pathways of energy dissipation48, is intensified upon water content rise. Lubrication of water films also enhances particle movement with resultant larger deformation and more energy loss22. Higher confining pressure induced further soil consolidation, from which particle movement was inhibited due to limited pore space, and manifested as a decline of the damping ratio.

The backbone curves of samples from five sampling sites were plotted in Fig. 6a, with the test data at w = 18%, σ3c = 100 kPa as an example. The lower the clay activity, the higher the dynamic shear stress for a given dynamic shear strain. A marked uprise in the backbone curve was noted at αc = 0.48 (Weinan) with higher peak dynamic shear stress at failure, compared to those from the other four sites. The slope also rises with lower clay activity, implying greater Gd. More clay particles are present in low clay activity samples to form cemented aggregates with medium- and small-sized pores dominated49, which accounts for the above phenomena. Whereas a converse trend was observed in Fig. 6b that Gd0 declined with lower clay activity, and the effect of confining pressure was more marked than that of water content. The proportionality of Gd0 to αc probably relates to particle morphology, skeletal deformation, and cementing materials (e.g., calcium carbonate or CaCO3). More clay particles attached to the surface of coarse particles reduce shape irregularity and surface roughness, leading to a weakening or even failure of the occlusion ability and a greater susceptibility to deformation, as the first point. The second is pore compression that dominates soil deformation at lower stresses, as coarse particles show greater elasticity and stiffness than fines. For low clay activity loesses, aggregates composed of more clay but fewer coarse particles exhibit lower stiffness, resulting in greater dynamic shear strain and lower Gd0. CaCO3 content also contributes to the rigidity of loess aggregates50. Liu51 established an empirical relationship for estimating the CaCO3 content of loess, i.e., CaCO3 (%) = − 9.470 + 9.431Kd, where Kd is the mass ratio of silt and sand to clay. The higher the clay content, the lower the CaCO3 content, and the lower the rigidity of aggregates, which leads to lower Gd0.

The λ-γd curve at w = 18%, σ3c = 100 kPa in Fig. 6c uprises with higher clay activity αc, with the most marked uprise occurring at αc = 0.82 (Baoji). Larger increment in λ was noted at higher αc, particularly when αc = 0.75–0.82, as seen from the λmax-αc curve in Fig. 6d. The rises in the value and increment of λ with higher clay activity may be attributed to the energy loss caused by the friction in relative particle motion when less clay particles were present to enlarge intergranular space and the extension of energy transport range within gaseous matter with lower energy density in soil pores. Moreover, pronounced moisture effect on λmax was noted in low clay activity cases, and vice versa, the effect of confining pressure is more prominent. The higher the clay content, the lower the λmax, owing to the strong water adsorption of clay and the high viscosity of pore water; conversely, lower clay content and looser soil skeleton allow for larger consolidation under confining pressure to suppress the increment in λmax.

Hardin-Drnevich model incorporating the clay activity of intact loess

The Hardin-Drnevich model approximates the backbone curve as hyperbolic and utilizes the dynamic shear modulus function Gd=G(γd) and damping ratio function λ = λ(γd) to respectively characterize nonlinearity and hysteresis12. A general form of the Hardin-Drnevich model was:

The dynamic shear modulus function can be derived as:

where τmax is the maximum dynamic shear stress; γr is the reference strain, defined as τmax/Gd0.

Let a = 1/Gd0, b = 1/τmax, we get:

The parameters a and b could be determined from the intercept and slope of the γd/Gd versus γd curve. The γd/τd versus γd relationship of the intact loess (Baoji) was plotted in Fig. 7, which is roughly linear that conforms to Eq. (4) or the hyperbolic model in Eq. (2) with the coefficient of determination R2 = 0.992–0.996 and the residual mean square error RMSE = 9.782 × 10− 6−5.316 × 10− 5.

The Hardin-Drnevich model presumes that the hysteresis loop is elliptical. In practice, however, this condition is often poorly satisfied. Thus, the damping ratio function was expressed as12:

Substituting Eq. (3) into Eq. (5), we get:

where λmax is the maximum damping ratio.

Considering the dependence of the dynamic properties of intact loess on clay activity (Fig. 6), the dynamic shear modulus function and the damping ratio function were modified from the γr-αc relationship. Data in Fig. 8a show an approximately parallel γr-αc relationship in double-logarithmic coordinates, with the mean slope of k = − 2.059, and a power function was derived below:

where m is an empirical parameter. In Fig. 8b, the γr calculated coincides well with test data.

The modified dynamic shear modulus function can thus be obtained by substituting Eq. (7) into Eq. (3):

Comparisons of measured and calculated Gd/Gd0 of intact loess are shown in Fig. 8c, where most of the data points fall within the ± 30% relative error lines and R2 = 0.857–0.997 for Gd (Table 3). It proves that Eq. (8), which includes the clay activity, is valid for characterizing the dynamic shear modulus of intact loess from five sampling sites.

In Fig. 9, the calculated data for the λ/λmax versus 1-Gd/Gd0 relationship at n = 1 deviate largely from test data. Hence, the damping ratio function was modified by introducing an exponent n and substituting Eq. (7) into Eq. (6), we get:

where n is a parameter that depends on the soil physical properties and test condition.

Fit results in Fig. 10a indicate that the λ/λmax data points are more clustered on the y = x line compared to Gd/Gd0, mainly in a higher range of λ/λmax values after removing some of the anomalous data points. Besides, the calculated γd/γr values (Fig. 10b) roughly agree with test data, and most data points lie around the y = x line but concentrated in the lower range of γd/γr values. The above results indicate that the modified damping ratio function well predicts the damping ratio of intact loess with R2(λ) = 0.634–0.983 (Table 3).

Water retention behavior of intact loess

Effect of clay activity on water retention curve of intact loess

Matric suction rises with lower water content or clay activity in the water retention curves of intact loess (Fig. 11a). Below w = 22%, the effect of clay activity becomes more noticeable; otherwise, the data points mostly overlap as the samples approach saturation. This aligns with the relationship between matric suction and clay activity in Fig. 11b. For the intact loess, the lower the clay activity, the higher the clay content and specific surface area (Table 1), which enhances water adsorption capacity and macroscopically the matric suction within the low water content range, as reflected by the steeper slope of the ψm-αc curve at w = 6% (Fig. 11b). Besides, more soluble salts are included in low-clay activity loess (Table 2). Hydration of soluble salts contributes to increased matric suction, whereas the dissolved salts in pore water primarily influence osmotic suction and do not directly alter matric suction52. Upon saturation, capillarity becomes the dominant mechanism governing water retention in intact loess, and matric suction is far lower than in the dry state53. Given that all samples were prepared at a dry density of 1.6 g/cm³ and characterized by a narrow range of specific gravity (2.69–2.71), the resulting porosity only varied between 0.405 and 0.410. This may account for the small variance in matric suction among samples near saturation. The above observations coincide with the negative correlation between matric suction and clay activity of remolded loess from eight sites across the Loess Plateau4. However, intact loess retains its natural structure, formed over long-term geological processes, including particle arrangement, cementation distribution, and presence of macropores, which are absent in remolded loess. This structural difference significantly influences water retention behavior. For instance, Ng et al.54 reported more pronounced hysteresis between 0 and 400 kPa and 4–140 MPa in intact loess than recompacted samples, indicating distinct water retention curves upon drying and wetting paths, which was attributed to ink-bottle pore neck effects or constricted pores.

Clay activity-based Van Genuchten model for intact loess

The van Genuchten model55 in Eq. (10), a classic model in soil physics and geotechnical engineering, was employed to optimally fit the water-retention data of intact loess in Fig. 11a, and the results are listed in Table 4.

where wr and ws are the residual and the saturated water content (%); α is the reciprocal of air-entry value (1/kPa); nv and mv are model parameters, mv=1–1/nv.

Statistical results indicate that the model well reproduces the water-retention curves of intact loess from five sampling sites, with R2 = 0.97–0.98. Among the fitted parameters, the residual water content wr varies minimally (5.0%−5.4%). From the water-retention theory of Lu52, clay content is highly linked to the adsorption-dominated water-retention mechanism under low moisture conditions. Given that the clay content across the test samples varies within a narrow range (18.91%–24.83%), the mean of wr=5.3% with a standard deviation of 0.17% could be adopted for practical applications. Furthermore, the parameters nv and αv are approximately linearly related to clay activity; the higher the clay activity, the greater the values of both parameters (Fig. 12a). By incorporating these linear correlations into Eq. (10), a modified van Genuchten model that accounts for clay activity is established. Model predictions well coincide with the test data (Fig. 12b), which well captures the water-retention behavior of intact loess. Statistical results indicate an overall deviation within ± 2% between measured and predicted water contents, with the median deviation approaching zero. It can be inferred that matric suction macroscopically characterizes the moisture state of the unsaturated intact loess and could also serve as a bridge for further understanding the correlation between water content and dynamic indexes in Fig. 6. The role of clay activity in the above relationship will be discussed in Sect. 4.1.

Microstructure of intact loess

Microstructural morphology of intact loess samples

SEM images of intact loess at 1000 magnification are shown in Fig. 13, where three samples from each site were taken. The native soil skeleton mainly consists of fine particles, where silt (A1: 10–50 μm) dominates, followed by clay (C), with irregular prismatic and lamellar shapes, which coexist as mono-particles and aggregates (A3). Soil particles were mainly in point contact and surface cementation. Both mosaic pores (P1) and overhead pores (P2) were formed by cementation (A2), which partly show a mosaic profile (e.g., XY-1). The microstructure of intact loess also manifests a potential link with clay activity. The intact loess (BJ) contains the largest proportion of fines, with larger particle sizes and angular shapes, corresponding to the highest clay activity (αc = 0.82). Soil particles aggregate to a modest degree, with the primary types of contact being point-to-point or point-to-surface contacts. Most pores are regularly shaped overhead pores, with a small quantity of narrow pores in between. In such a soil, most clay particles are dispersed in the pore space, with a small amount attached to the surface or contact points of silt, which manifests itself as coatings on aggregates. Following the decline in clay activity, mono-particles tend to form aggregates with clay and cementation materials filled, and this type of structural unit markedly rises. Particle contacts appear mainly in mosaic form with partially oriented features, e.g., XY-1 and XY-2. The diameter of the overhead pore declines, with the majority of 2–5 μm (YL-2), but locally larger overhead pores are still present, e.g., XY-3. For the intact loess in Xi’an (αc = 0.60), e.g., XA-1 and XA-2, more clay particles are adsorbed or even spread over the surface of silt to act as coatings. Strip-shaped particles and cementation materials filled in soil pores to manifest a more pronounced mosaic structure with more aggregates. Lamellar clay particles are visible in the intact loess (WN), corresponding to the lowest clay activity, and overhead pores can hardly be noticed, leaving only a few mosaic pores (< 2 μm) on the surface of aggregates. Clay and cementation materials act as coatings that wrap around and isolate the silt to form a granular group of soil skeleton. This roughly coincides with the study of Gao57 that loess microstructure in China transitions from granular overhead contact in the northwest to clod mosaic cementation in the southeast. In general, the clay activity of intact loess declines from west to east (from Baoji to Weinan), and fewer overhead pores but more mosaic pores are present with aggregates to account for the more stable structure. The above microstructural profiles of intact loess confirm the variations of dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio with clay activity (Fig. 5).

Effect of clay activity on quantified microstructural indexes of intact loess

In Fig. 14, except for the probability entropy Hm, the other microstructural indexes characterizing the pore morphology of the intact loess all show monotonic responses to changes in clay activity. The probability entropies Hm are all above 0.98, which suggests that the pore system of the intact loess is weakly orientated and randomly arranged. The shape coefficient ff rises with higher clay activity, which corresponds to more rounded soil pores with lower roughness of pore edges. The fractal dimension Df ranges from 1.19 to 1.29, which suggests less complexity of the pore system. The pore porosity distribution fractal dimension Dc declines with higher clay activity, which implies the lower variance in pore size among the detected pores, i.e., the pore morphology tends to be homogenized. The area probability distribution index ba declines with higher clay activity, with more macropores but fewer small pores, and the contact mode between soil particles transforms from surface cementation to point contact. Overall, the pores of the intact loess lack evident orientation, whereas in the case of higher clay activity or lower clay content, more developed macropores and mono-particles (fewer aggregates) lead to a homogenized pore system, which transforms from the mosaic to the overhead mode. Correlation between the above microstructural indexes and dynamic properties of intact loess, as well as the influence of clay activity, will be discussed in Sect. 4.1.

Soil microstructure is a complex, discontinuous, and heterogeneous three-dimensional system, whereas SEM images only represent two-dimensional projections of such structures. Accurately inferring pore connectivity, real morphology, and spatial arrangement of particles is challenging due to observation angle restrictions. Images captured from any single orientation cannot fully represent soil microstructure that exhibits directionality due to factors like depositional history. Anisotropy quantification necessitates the preparation and observation of multiple samples from various angles, which presents both technical and statistical challenges. This is in addition to potential structural disturbances introduced during sample preparation. Interparticle contacts and pore morphologies may be obscured by the artificial cutting and polishing of the flat sections under examination, which may impair the original particles and pores along the sections. Uncertainties also arise in the quantitative processing of SEM images, such as the subjectivity of image binarization, where small changes in the grayscale threshold can significantly influence derived metrics like particle size distribution and porosity. The magnification level of SEM images also critically affects the validity of quantitative analysis. While high resolution allows the identification of finer clay particles and pores, it reduces the field of view, thereby compromising representativeness. Conversely, a larger field of view under lower magnification may fail to resolve small yet structurally significant features such as micro-cracks. Therefore, in this study, three samples from each sampling site were examined, and statistics of microstructure parameters quantified by the PCAS software46 were included. This method aims to provide robust microscopic evidence for analyzing the dynamic characteristics of intact loess.

Discussions

Influence of matric Suction and microstructure on the dynamic behavior of intact loess

The initial dynamic shear modulus Gd0 and maximum damping ratio λmax of intact loess at five sampling sites (σ3c = 100 kPa and w = 16%, 18%, 20%) are plotted against matric suction and microstructural indexes (f, Df, Dc, ba) in Figs. 15 and 16. The probability entropy Hm, which bears poor correlation with clay activity, is not considered here. A contradictory relationship was seen in Fig. 15 that for the intact loess from each site, Gd0 rose with lower water contents or higher matric suction, whereas for those from five sites at a given water content, Gd0 declined with higher matric suction. The former is primarily linked to the moisture-mediated mobilization of inter-particle friction within soil skeleton under cyclic loading. The lower the water content, the higher the matric suction, and the less the capillary water, beyond the adsorbed water on clay surfaces, that plays this role52. Thus, the lubrication effect facilitating particle mobilization weakens to enhance effective stress and interparticle frictional resistance, corresponding to higher resistance of soil skeleton to deformation. The trend observed in the latter case relates to variations in clay activity of intact loess, i.e., matric suction is negatively correlated with clay activity. Lower clay activity corresponds to more clay and fewer coarse particles, resulting in a lower Gd0, which depends primarily on coarse particle content of soil11. The microstructural profile of intact loess also indicates a close relationship with Gd0. The greater the shape parameter ff, the closer the soil particles are to spherical, and the less pronounced the rough edges become. Fewer clay particles adhere to the aggregate surface, resulting in less pronounced aggregate breakage under cyclic loading, but instead exhibiting higher deformation resistance or higher Gd0. The fractal dimension Df is negatively correlated with ff58, such that lower Df corresponds to higher Gd0. A higher Dc value indicates coarser and more irregular pore edge morphology, where more clay particles adhere to coarse particles to form aggregates, allowing for greater deformation under cyclic loading (lower Gd0). The lower the ba value, the greater the coexistence of micro-to-medium pores and fewer macropores in soil, resulting in enhanced deformation resistance (or higher Gd0). It can be inferred that matric suction does not act solely on Gd0; the particle composition and microstructure of loess should also be considered. The closer the particle morphology approaches sphericity, the smoother the pore edges, and the more uniform the pore distribution, the higher the Gd0 of intact loess.

The relationship between the maximum damping ratio and matric suction of intact loess follows a consistent trend (Fig. 16): a higher water content or lower matric suction corresponds to an increased maximum damping ratio. The underlying physical mechanisms may be attributed to three main aspects. First, under conditions of high water content or low matric suction, the water film surrounding soil particles acts as a lubricant, promoting relative sliding, rolling, and rearrangement of particles during cyclic loading. Second, cyclic loading induces rapid relative motion between pore water and soil skeleton. Given the inherent viscosity of water, this motion results in energy dissipation. A higher water content increases the volume of water involved in such relative motion, thereby enhancing energy dissipation. Third, at increased water contents, soil skeleton becomes more compliant (reflected by a reduced dynamic shear modulus), leading to greater strains, including irreversible plastic strain, under identical cyclic stress conditions. This inherently consumes considerable energy. Thus, higher water content facilitates the transition of the soil into a plastic state under cyclic loading, enabling greater energy dissipation through plastic deformation and resulting in an increased damping ratio. Regarding the relationship between microstructural indexes and maximum damping ratio, particles with more rounded shapes (higher ff), more continuous gradation (higher Df), smoother pore boundaries (lower Dc), and more homogeneous spatial distribution of pores (lower ba) facilitate particle rearrangement. These microstructural characteristics also contribute to enhanced energy dissipation, thereby increasing the damping ratio.

Engineering implications of clay activity for seismic evaluation of loess ground

Clay activity, as a synthetic index integrating two major soil properties, such as particle composition and consistency, has brought forth its theoretical value in soil mechanics. Clay activity governs interparticle interactions and damping characteristics, as evidenced by the more pronounced dynamic modulus decay and damping ratio increment exhibited by high-clay activity loess under cyclic loading (Fig. 4b and d). It is thus imperative to further investigate the relevance of clay activity to the dynamic properties of loess and to incorporate this into the dynamic constitutive model for loess. Likewise, this holds potential significance for seismic safety assessment of loess sites.

For evaluation of seismic collapse susceptibility in loess fields, in addition to indexes characterizing dynamic loads such as consolidated stress and vibration frequency, the seismic collapse coefficient is typically estimated based on physical properties like void ratio and liquidity index10,11. This method, grounded in extensive experimental data, identifies some inducing factors for seismic collapse in loess; however, essential physical indexes that identify soil species, such as clay content and plasticity index, have not been explicitly included in calculation methods for the seismic collapse coefficient. Given the link between clay activity and microstructural morphology identified in this study, such as the influence of clay on soil particle cementation, clay activity may serve as a fundamental criterion for evaluating loess seismic subsidence at different depths on one site or across multiple sites, in addition to the physical indexes currently considered in such applications7. Another potential application is liquefaction characterization for loess sites. Traditional seismic liquefaction evaluations have primarily focused on saturated sands and silts, where clay content serves as a critical metric for identifying liquefaction potential3. Liquefaction in loess also draws particular attention5, with its occurrence contingent upon site conditions (topography, stratigraphy, and groundwater recharge), pore structure (changes in medium and small pores), seismic loading (such as peak ground acceleration), and soil properties (water content, dry density, and plasticity index)11. In terms of liquefaction mechanisms, the water-retention capacity of loess influences the transition from unsaturated to saturated states, which is significantly correlated with clay activity. This also implies the importance of the plasticity index identified in previous studies as a fundamental geotechnical parameter. However, attention should be paid to the fact that for loess with generally high plasticity indexes (Ip>20), liquefaction potential is typically disregarded11. Alternatively, the influence of the plasticity index and the threshold clay content specified in current standards could be integrated into loess liquefaction evaluation by introducing clay activity.

The challenges of applying clay activity in engineering practice must be acknowledged despite its potential significance. Clay activity, converted from clay content and plasticity index, requires measurement through particle gradation and Atterberg limit tests. Particular attention should be paid to the reliability of measurements compared to conventional physical property tests alone, e.g., replicate tests are necessitated to eliminate any error from either test. The lack of a comprehensive database on clay activity across different loess regions and its quantitative relationship with dynamic indexes such as dynamic modulus and damping ratio remains a challenge. Theoretical models remain immature, and extensive studies on how to incorporate clay activity into the mechanics-based constitutive models and seismic response programs have yet to be implemented. Additional studies should involve rigorous fundamental tests, establishment of regional clay activity databases, and intensive exploration of the relationship between clay activity and dynamic parameters acquired from field and laboratory tests to facilitate its engineering application.

Conclusions

This study investigated the correlation between the dynamic properties and clay activity of intact loess from five sampling sites in Weihe Basin, with evidence drawn from both microstructure and water-retention perspectives. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) Dynamic properties of intact loess are highly linked to clay activity, manifested as the uprising of the backbone curve with lower clay activity, along with higher dynamic shear modulus and lower damping ratio. Reference strain was approximated as a power function of clay activity, which was introduced into the dynamic shear modulus function and the damping ratio function of the Hardin-Drnevich model. The effect of clay activity on the dynamic stress-strain characteristics of intact loess was rationally characterized.

(2) Matric suction of intact loess is negatively correlated with clay activity. The higher clay content and larger specific surface area, which predominates in adsorption, probably explain the increased matric suction at low clay activity. The van Genuchten model well characterized the water-retention curves of intact loess, where the parameters nv and αv were approximated as positive linear functions of clay activity. Matric suction does not act independently on the initial dynamic shear modulus, but particle composition and microstructure contribute as well. The maximum damping ratio is negatively correlated with matric suction, and increased water content leads to higher viscous energy dissipation, a vital factor in the rise of the maximum damping ratio at lower matric suctions.

(3) SEM images of the intact loess indicate that pores are weakly orientated and randomly arranged in the case of higher clay activity, with more developed macropores and mono-particles (fewer aggregates) in the homogenized pore system, which transforms from the mosaic to the overhead mode. The shape coefficient rises with higher clay activity, while the fractal dimension, pore porosity distribution fractal dimension, and area probability distribution index tend to decline. The probability entropy varies around 0.99, which is less relevant to clay activity. The closer the particle morphology approaches sphericity, the smoother the pore edges, and the more uniform the pore distribution, the higher the initial dynamic shear modulus and the maximum damping ratio, corresponding to higher clay activity.

The above results preliminarily highlighted the importance of clay activity to evaluating the dynamic behavior of intact loess with varying textures, which can be further refined from extensive dynamic test results of intact loess from diverse terrains and sedimentary chronology. This also holds potential significance for seismic safety evaluation of loess grounds, e.g., seismic collapse and liquefaction susceptibility.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Shao, Z. et al. Assessment of strong earthquake risk in the Chinese Mainland from 2021 to 2030. Earthq. Res. Adv. 3 (1), 100177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eqrea.2022.100177 (2023).

Ji, K., Wen, R., Ren, Y., Wang, W. & Chen, L. Disaggregation of probabilistic seismic hazard and construction of conditional spectrum for China. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 19, 5769–5789 (2021).

He, S. et al. The study on loess liquefaction in china: a systematic review. Nat. Hazards. 103, 1639–1669 (2020).

Wang, S., Ye, W., Wang, Y. & Ding, J. Evaluation of the relationship between freezing point and clay activity of loess. J. Soil. Sediment. 22 (8), 2262–2280 (2022).

Deng, L., Zhang, C., Fan, W., Cao, Y. & Mao, W. Three-dimensional microstructure evolution of loess liquefaction based on the µm-CT quantitative observations. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 178, 108442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2023.108442 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Collapsibility, composition, and microstructure of loess in China. Can. Geotech. J. 53, 673–686 (2016).

Qiu, J., Wang, X., Lai, J., Zhang, Q. & Wang, J. Response characteristics and preventions for seismic subsidence of loess in Northwest China. Nat. Hazards. 92, 1909–1935 (2018).

Wu, Z., Zhang, D., Wang, S., Liang, C. & Zhao, D. Dynamic-response characteristics and deformation evolution of loess slopes under seismic loads. Eng. Geol. 267, 105507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105507 (2020).

Che, G. et al. Experimental study on the influence of seismic subsidence of loess under bidirectional loading modes. Earthq. Res. Adv. 1 (4), 100064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eqrea.2021.100064 (2021).

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. Standard for Seismic Design of Underground Structures (GB 51336 – 2018, 2018).

Wang, L. Loess Dynamics (Seismological, 2003). (in Chinese).

Das, B. M. & Ramana, G. V. Principles of soil dynamics (2nd edition)CL Engineering, (2011).

Tian, W. et al. Research progress and frontier scientific problems in loess dynamics. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 37 (11), 2119–2127 (2015). (in Chinese).

Zhou, Z., Ma, W., Zhang, S., Mu, Y. & Li, G. Effect of freeze-thaw cycles in mechanical behaviors of frozen loess. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 146, 9–18 (2018).

Wu, H., Shao, S., Shao, S., Zhang, S. & Wang, Z. Variations in dynamic shear modulus of loess exposed to dry-wet cycles from xi’an area, China. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 173, 108126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2023.108126 (2023).

He, R., Hao, Y. & Zhou, Z. Experimental study on the dynamic properties of undisturbed loess under moistening conditions in Zhengzhou, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-024-03698-7 (2024).

Yang, W., Pan, B., Jin, L., Wang, Y. & Saleem, F. Experimental study on dynamic characteristics of Qingyang loess under different water contents. Arab. J. Geosci. 13, 986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-020-05989-1 (2020).

Chen, H., Li, H., Fu, R. & Yuan, X. Dynamic behaviour and damage characteristics of loess in Xianyang, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 2285–2297 (2020).

Xiao, J., Li, H., Zhang, S., Jiang, N. & Ma, Y. Experimental study on dynamic properties of loess in Xining area under Cyclic loading. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 153 (03), 032014. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755 (2018).

Wang, Z., Luo, Y., Guo, H. & Tian, H. Effects of initial deviatoric stress ratios on dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of undisturbed loess in China. Eng. Geol. 143–144, 43–50 (2012).

Jiang, Y., Chen, H. & Leng, G. Dynamic elastic modulus of Xianyang loess based on microscopic analysis: a qualitative evaluation. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 26 (8), 3331–3356 (2020).

Mitchell, J. K. & Soga, K. Fundamentals of soil behavior (3rd edition). (John Wiley & Sons Inc., (2005).

Cheng, X., Li, X., Nie, J. & Liu, H. Research on the dynamic parameters of loess. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 37, 77–93 (2019).

Fu, Y. et al. The dynamic characteristics of saturated remolded loess under Cyclic load. Earthq. Res. Adv. 4 (2), 100235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eqrea.2023.100235 (2024).

Song, B., Tsinaris, A., Anastasiadis, A., Pitilakis, K. & Chen, W. Small to medium strain dynamic properties of Lanzhou loess, China. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 163, 107454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2022.107454 (2022).

Wang, Z., Luo, Y., Wang, R., Yang, L. & Tan, D. Experimental study on dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of undisturbed loess in different regions. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 32 (9), 1464–1469 (2010). (in Chinese).

Wang, Q., Zhong, X., Li, N., Ma, J. & Liu, Z. Experimental research on difference of dynamic modulus and damping characteristics of loess in Shanxi Province. IOP Conf. Ser: Mater. Sci. Eng. 452 (3), 032048. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/452/3/032048 (2018).

Wang, L., Li, X., Zhao, N. & Hong, B. Effect of clay content on physical and mechanical properties of loess soils. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard. Control. 29 (3), 133–143 (2018). (in Chinese).

Li, L., Wang, L. & Shi, Y. Effect of clay on liquefaction of loess in Gansu. World Earthq. Eng. 23 (4), 102–106 (2007). (in Chinese).

Skempton, A. W. The colloidal activity of clays. Proc 3rd Int. Conf. Soil. Mech. Found. Eng. (Switzerland) (1984).

Pandian, N. S. & Nagaraj, T. S. Critical reappraisal of colloidal activity of clays. J. Geotech. Eng. 116 (2), 285–296 (1990).

Polidori, E. Reappraisal of the activity of clays. Activity chart. Soil. Found. 49 (3), 315–327 (2009).

Subramaniam, P. & Banerjee, S. Shear modulus degradation model for cohesive soils. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 53, 210–216 (2013).

Sağlam, S. & Bakır, B. S. Cyclic response of saturated silts. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 61–62, 164–175 (2014).

Lin, B., Zhang, F., Feng, D., Tang, K. & Feng, X. Dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of thawed saturated clay under long-term Cyclic loading. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 145, 93–105 (2018).

Wang, H., Sun, P., Liu, E. & Li, R. Dynamic properties of Tianshui saturated remolded loess: a laboratory study. Eng. Geol. 272, 105570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105570 (2020).

Yang, L., Shao, S., Sun, Q. & Wang, P. Experimental study on the dynamic modulus of compacted loess under bidirectional dynamic load. Earthq. Res. Adv. 2 (3), 58–66 (2020).

Liao, H., Zhang, Z., Ning, C., Liu, J. & Song, L. Analysis of dynamic stress-strain relationship of loess. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 22 (31–32), 5559–5565 (2008).

Wu, Z., Xu, S., Chen, D., Zhao, D. & Zhang, D. An experimental study of the influence of structural parameters on dynamic characteristics of loess. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 132, 106067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2020.106067 (2020).

Groholski, D. R. et al. Simplified model for small-strain nonlinearity and strength in 1D seismic site response analysis. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 142 (9). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001496 (2016).

Dejaloud, H. & Rezania, M. Double image stress point bounding surface model for monotonic and Cyclic loading on anisotropic clays. Acta Geotech. 18, 2427–2456 (2023).

Ministry of Water Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Standard for Geotechnical Testing Method (GB/T 50123 – 2019, 2019).

Huang, W. et al. Evaluating knickpoint retreat along the Qinling North Piedmont fault for paleoseismological analysis during holocene. Quaternary Sci. 42 (3), 843–857 (2022). (in Chinese).

Matsuoka, H. Soil Mechanics. Translated by Lou Ting, Yao YangpingChina Water and Power Press,. (in Chinese) (2001).

ASTM International. Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System) ASTM D2487-17e1. (2017).

Liu, C., Shi, B., Zhou, J. & Tang, C. Quantification and characterization of microporosity by image processing, geometric measurement and statistical methods: application on SEM images of clay materials. Appl. Clay Sci. 54 (1), 97–106 (2011).

Chipman, J., Kiefer, R. W. & Lillesand, T. Remote Sensing and Image Interpretation 7th edn (Wiley, 2015).

Baghbani, A., Costa, S., Faradonbeh, R. S., Soltani, A. & Baghbani, H. Modeling the effects of particle shape on damping ratio of dry sand by simple shear testing and artificial intelligence. Appl. Sci. 13 (7), 4363. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13074363 (2023).

Xie, D. Soil Dynamics (Higher Education Press, 2011). (in Chinese).

Lu, Y. Pleistocene Climatic cycles and variation of CaCO3 contents in a loess profile. Chin. J. Geol. 16 (2), 122–131 (1981). (in Chinese).

Liu, D. Loess and the Environment (Science, 1985). (in Chinese).

Lu, N. Generalized soil water retention equation for adsorption and capillarity. J. Geotech. Geoenviron Eng. 142 (10), 04016051 (2016). 10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001524.

Leong, E. C. & Wijaya, M. Laboratory Tests for Unsaturated Soils (CRC, 2023).

Ng, C. W. W. et al. Water retention and volumetric characteristics of intact and re-compacted loess. Can. Geotech. J. 53, 1258–1269 (2016).

van Genuchten, M. Th. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil. Sci. Soc. Am. J. 44 (5), 892–898 (1980).

Schofield, A. & Wroth, P. Critical State Soil Mechanics (McGraw-Hill, 1968).

Gao, G. Loess microstructure in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 25 (20), 945–948 (1980). (in Chinese).

Sezer, G. İ., Ramyar, K., Karasu, B., Göktepe, A. B. & Sezer, A. Image analysis of sulfate attack on hardened cement paste. Mater. Des. 29 (1), 224–231 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Nos. 42027806 and 52378368]. These supports are greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiulong Ding, Songhe Wang wrote the main manuscript text and Xuwei Zhao, Shuai Niu prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, J., Zhao, X., Niu, S. et al. Correlation between clay activity and dynamic properties of intact loess: evidence from microstructure and water-retention capacity. Sci Rep 16, 1665 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31196-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31196-7