Abstract

Fatigue failure of concrete under action of freeze-thaw cycles and repeated loading posess a critical challenge seasonally frozen soil regions, and concrete reinforcement technology offers a viable solution to this issue. However, based on current research results, BFRP, as a relatively young member of FRP materials, has not been fully studied in the field of interfacial bonding. This study emphasizes the importance of concrete fatigue resistance in seasonally frozen regions and aims to provide a theoretical basis for the practical application of BFRP-reinforced concrete therein. In this work, BFRP was employed in concrete reinforcement technology, and the fatigue characteristics of BFRP-concrete under freeze-thaw cycles were evaluated through double shear tests and finite element analysis. The test results demonstrated that freeze-thaw damage gradually propagated from the concrete surface to the interior, and the thickness of concrete layer peeled off by the adhesive layer decreased progressively with freeze-thaw cycles increasing. Double shear test results showed that the interfacial shear strength of BFRP-concrete decreased by approximately 46.86% after 200 freeze-thaw cycles. Then, finite element analysis further revealed that freeze-thaw cycles exerted the larger adverse impact on the fatigue life of BFRP-concrete than stress amplitude.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As one of the five environmental exposure conditions of concrete structures, the freeze-thaw environment causes severe threat to the structure durability. In China, the concrete structures in high-latitude cold regions have suffered significant damage due to repeated freeze-thaw cycles. For structures subjected to sustained long-term fatigue loads, such as viaducts and industrial buildings, the presence of stress concentration zones within and on the concrete surface exacerbates performance degradation1, after freeze-thaw exposure, these structures exhibit stiffness reduction and accelerated damage progression, making these structure reinforcement an urgent priority.

After years of unremitting efforts, China has gradually developed and matured in the field of FRP-reinforced structures2. Compared with traditional reinforcement methods, FRP reinforcement offers advantages including light weight, high tensile strength, excellent corrosion resistance, superior design performance and simple construction process3,4,5,6. BFRP exhibits outstanding performance in corrosion resistance7 and high-temperature stability8, and has gradually become an important part of the FRP reinforcement field.

Many domestic and international scholars have conducted a lot of research on the failure mechanism of freeze-thaw cycles. The famous hypothesis and theories are the hydrostatic hypothesis proposed by T.C. powers9,10, the osmotic pressure hypothesis proposed by T. C. powers and Helmuth R. A to supplement hydrostatic pressure hypothesis11,12, the freeze-thaw failure theory proposed by Litvan13and the critical water saturation hypothesis proposed by Fagerlund14,15, etc.

Chaoying Zou et al.16 explored the degradation mechanism of concrete in freezing-thawing environment, measuring three mechanical properties of concrete after freeze-thaw cycling: dynamic elastic modulus, splitting tensile property, and fatigue load resistance. Based on the test results, they summarized the degradation laws of these three properties and proposed empirical formulas. Tang17 defined the freeze-thaw damage using damage mechanics, established the damage evolution equation and the evolution model of principal stress failure surface, which can effectively predict the strength variation of concrete after freeze-thaw.

Fatigue failure induces permanent damage, thus, studying the fatigue performance of interfaces is of great significance. Li and Wang18 conducted fatigue tests with varying adhesive layer thicknesses, establishing a correlation between interface damage, stiffness degradation, and adhesive layer thickness. They found that a thicker adhesive layer results in better energy dissipation. Ma et al.19 studied the failure process of bonded interfaces under fatigue loading and obtained three modes of interface failure. Chou et al.20 analyzed factors such as the fatigue life, stress distribution, and hysteresis curves of near-surface mounted (NSM) CFRP -concrete bonded interfaces, and investigated the correlation between fatigue stress amplitude, bonding length and interface fatigue bonding performance.

They found that the bond performance at the interface between NSM CFRP and concrete is significantly affected by fatigue load. Peng et al.21 studied the effect of bond length on the interfacial bond strength of NSM CFRP-concrete. The results indicate that when the failure mode is interfacial debonding, NSM CFRP system with a longer bond length exhibits more significant degradation in bond capacity compared to that with a shorter bond length. Carloni et al.22,23 observed the fatigue performance of FRP concrete interface using digital image technology and obtained the stress transfer phenomenon at the interface during fatigue loading. Yuan et al.24 conducted mechanical performance tests on 12 fabricated specimens, and proposed a formula for correcting the effective bonding length of the AFRP-concrete interface. Longqiang Tian25 investigated the influence of fatigue loading on the interfacial properties of BFRP-concrete double shear specimens under multiple variables, establishing the patterns that govern interfacial delamination failure. He proposed an empirical formula describing the three-stage degradation of interfacial stiffness. However, the impact of freeze-thaw cycles on this degradation was not accounted for. Experimental methods mainly include single shear test and double shear test and the specific methods are different. Yanchun Yun et al.26 investigated the durability of FRP concrete bonding interface under freeze-thaw conditions through single shear test.The results show that the bond strength, bond stiffness, interfacial fracture energy, and maximum slip decrease with freeze-thaw cycles increasing. Gao27 obtained from the CFRP concrete single-side shear test that the adhesive layer and concrete strength have a great influence on the bonding, and concluded that the adhesive layer can reduce the strain and inhibit the damage. Peng et al.28 investigated the fatigue performance of CFRP-concrete interface by double-sided shear tests and concluded that the greater the adhesive layer thickness and bonding length, the better the effect of inhibiting cracks.Zhong29 used unilateral lap test to investigate GFRP bridge deck joint, obtained the interfacial stress distributions, and proposed a construction method conducive to stress. Xiao et al.30 studied the interface bond between CFRP and concrete through single shear tests and determined the effective bond length of the CFRP-concrete interface. Diab et al.31 investigated the interfacial fatigue performance through double shear tests, and combined test data with the mechanical basis to develop the bond-slip model and interfacial crack propagation model under fatigue loading.

Predicting the fatigue life of the FRP-concrete interface under freeze-thaw conditions facilitates the timely strengthening of freeze-thaw-damaged structures and elongates their service life. Currently, few studies have been conducted in this area32,33,34, with existing research primarily focusing on the S-N curve method proposed by Waller and the fracture mechanics analysis method based on the Paris formula. However, the latter requires extensive testing to determine parameters, and its solution process is highly complex. Leusmann et al.35,36 investigated the interfacial bond fatigue performance through double shear test and obtained the relevant calculation formulas for fatigue life and load amplitude. Qiao37 studied the performance degradation of concrete specimens under freeze-thaw fatigue loading with different saturation levels.

Strain measurement and acoustic emission technology were used to monitor changes in concrete parameters. The results revealed the degradation mechanism of concrete under freeze-thaw-fatigue coupling and established a prediction model for its attenuation law and service life. Chou et al.20 conducted single shear pull-out tests under fatigue loading to investigate the interfacial bonding behavior and degradation mechanisms between NSM CFRP and concrete. They derived an S-N curve model applicable to delamination failure in NSM CFRP-strengthened concrete systems.

Currently, research on the fatigue failure modes of the BFRP-concrete interface under freeze-thaw conditions remains limited, particularly regarding the analysis and prediction of interfacial fatigue life under such conditions, which requires further investigation. The double shear test is a critical method for studying the fatigue failure modes of the BFRP-concrete interface. However, the biggest challenge of the double shear test lies in how to solve the eccentricity problem during the loading process. To resolve this, this study independently developed a set of double shear specimen fixtureswhich can effectively solve most eccentricity problems. This paper will analyze the fatigue failure modes and service life of the BFRP-concrete interface under freeze-thaw conditions to obtain corresponding variation laws and provide a theoretical basis for practical engineering applications.

Materials and sample preparation

The double-shear specimen consists of a concrete matrix, epoxy resin adhesive, and BFRP cloth. The mechanical properties of each constituent material directly influence the interfacial failure mode.

Concrete

The concrete strength grade is C40, and the cement used is P.O. 42.5 ordinary Portland cement. The mix ratio is water: cement: sand: stone = 185:349:695:1170, with continuously graded aggregate. The results indicate that the mechanical properties of the concrete meet the requirements for the double shear test. The basic mechanical properties of the cube specimens are shown in Table 1.

Material epoxy resin adhesive

The epoxy resin adhesive used is E-44AB low molecular epoxy resin produced by Shanghai Aotun Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. This type of adhesive offers advantages such as high strength, low shrinkage, and excellent adhesion to fiber composite materials. The mixing ratio is 1:1, with a full curing time of 24 h. Its mechanical properties are shown in Table 2, and the epoxy resin adhesive is illustrated in Fig. 1.

BFRP

The BFRP material used in the test was sourced from Shanghai Miaohan Construction Technology Co., Ltd. The BFRP cloth has a thickness of 0.167 mm. Its mechanical properties are shown in Table 3, and the BFRP cloth is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Specimen preparation

The dimensions of the double shear specimens are 150 mm×150 mm×200 mm, with an adhesive layer thickness of 1 mm, a bonding length of 120 mm, and BFRP fabric dimensions of 390 mm×50 mm. The preparation process for the double shear specimens is as follows.

Step 1: Use sandpaper to remove the surface concrete of the specimens, then spray an ethanol solution onto the polished surface and wipe it clean.

Step 2: Once the surface is dry, mark the outline of the bonding area on the specimen using a pencil, then attach 1-mm-diameter iron wires along the outline to control the adhesive layer thickness.

Step 3: Uniformly apply the prepared epoxy resin adhesive to the bonding area, ensureing the adhesive thickness is flush with the iron wires. Place the BFRP fabric onto the epoxy resin adhesive and roll repeatedly along the bonding direction with a roller brush until excess epoxy resin adhesive squeezes out from the fiber bundles, thereby ensuring full contact between the fabric and the adhesive.

The completed double shear specimen is shown in Fig. 3.

The specimen clamping tool utilizes a custom-fabricated double-shear fixture, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The fixture consists of two components: an upper chuck and a lower chuck. The upper chuck is designed as a hinge movable only in one direction, while the lower chuck is designed as a live hinge. In this way, the specimen can be loaded along the central axis, thereby effectively solve the eccentricity problem.

Experimental procedures

Static load and fatigue test

Prior to the static load and fatigue tests, the specimens were pretreated through freeze-thaw cycles. The freeze-thaw process was conducted in a GDWJ-800B high-low temperature alternating environmental test chamber. The freeze-thaw temperature was controlled within the range of -18 °C to 20 °C. Specimens were soaked and frozen in water, with each cycle lasting 4 h. The number of freeze-thaw cycles was set to 0 (control group), 100, and 200.

Strain distribution was measured by attaching strain gauges (Model: BFH120-5AA; resistance: 120 Ω) on the BFRP cloth. The gauge spacing was 20 mm, and the distribution of measurement points is shown in Fig. 5.

The static load test was conducted using a LA-2000 steel strand tensile testing machine. Loading was displacement-controlled at a rate of 0.1 mm/min. The ultimate load of each specimen was measured and recorded via a load sensor. The loading process is illustrated in Fig. 6.

The fatigue test is carried out on the basis of the static load test. The fatigue test is carried out on the PA-500 fatigue testing machine. The force control is adopted, the loading waveform is sine wave, and the loading frequency is 10 Hz. In order to better observe the process of interface fatigue failure, the upper limit value Pmax of the fatigue test load is taken as 70% of the static ultimate load. The stress ratio is 0.2, the specimen is preloaded first, and sinusoidal loading is started after the preloading is over. The specific loading method is shown in Fig. 7, and the specimen loading is shown in Fig. 8.

The fatigue tests were performed subsequent to the static load tests using a PA-500 fatigue testing machine. A force-controlled loading protocol was adopted, with a sinusoidal waveform and a loading frequency of 10 Hz. To facilitate observation of the interface fatigue failure process, the upper load limit (Pmax) for the fatigue tests was set to 70% of the static ultimate load, with a stress ratio (R) of 0.2. Prior to formal testing, specimens were preloaded; sinusoidal loading was initiated upon completion of preloading. The detailed loading protocol is illustrated in Fig. 7, and the specimen loading configuration is shown in Fig. 8.

The static load test specimens and fatigue test specimens are grouped as shown in Table 4.

Finite element analysis

Main principles

As one of the important numerical simulation methods, the finite element method has promoted the advancement of civil, mechanical, electrical, and other industries38. ABAQUS, recognized as one of the most authoritative finite element analysis software packages in the industry, offers a wide range of applications and robust nonlinear analysis capabilities39. As a large-scale general-purpose software, ABAQUS features a comprehensive and diversified material library. Its models can simulate the properties of actual engineering specimens more accurately under real working conditions, and the simulation results can also minimize discrepancies in fine structures. ABAQUS further includes an extensive range of material constitutive models, diverse failure criteria, a dedicated set of contact formulations, and compatibility with multiple analysis software tools, ensuring both result accuracy and user convenience.

Parameter settings

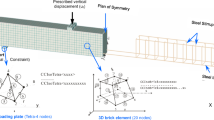

The numerical analysis using ABAQUS software consists of two parts: modeling and result computation. First, a finite element model of the double shear specimen was established, that the concrete strength grade is C40 and the mix ratio is consistent with that in the experiment. The concrete parameters for the numerical simulation were obtained from mechanical property tests of concrete cube specimens. For finite element analysis, the plastic damage model was adopted as the concrete’s damage constitutive model. C3D8I elements were selected to model the material properties, and the thermal stress analysis module was utilized. Relevant parameters are shown in Table 5.

The BFRP was modeled using the S4R element, with mechanical properties consistent with those in the experiment. Adhesive elements were used to simulate the epoxy resin adhesive layer, each component was created separately, assigned distinct material properties and element types, and contact definitions between components were subsequently established. The constitutive model of the adhesive elements adopts the bilinear model illustrated in Fig. 9.

ABAQUS provides six damage criteria, including Maxs Damage criterion. In the above model, the adhesive layer is primarily subjected to shear deformation; the stress at each stage of the adhesive layer can only be indirectly derived from the load at the loading end, while the displacement of the adhesive layer cannot be directly measured. Therefore, the Maxs Damage criterion is adopted to define the initial damage of cohesive elements, and the energy-based damage evolution law and linear stiffness degradation method are adopted. The damage criterion expression is:

In this paper, among the three thermal analysis programs provided by ABAQUS, the most suitable method selected for this experiment is the sequential thermal stress coupling analysis method .

For the boundary conditions, it is necessary to set the surface radiation of the material in Interaction and the ambient temperature amplitude in Create Boundary to simulate the effects of actual freeze-thaw cycles. To replicate the freeze-thaw conditions, the temperature fluctuates is defined to simulate the temperature fluctuation range of the freeze-thaw machine. The temperature fluctuates between 20 °C and − 18 °C with a cycle of 4 h. Figure 10 shows the temperature amplitude curve (Taking 100 freeze-thaw cycles as an example).

Model establishment

The static load simulation also employs displacement control, with one end fixed in a boundary condition and displacement applied to the RP point point at the other end. The RP is coupled to the concrete through MPC to transfer the displacement, as illustrated in Fig. 11 .

The fatigue simulation was performed using FE-safe software. After importing the completed double-cut specimen model, FE-safe automatically identified the specimen parameters and related settings. The upper fatigue limit Pmax was set to 65% of the corresponding static ultimate load, with other conditions remaining unchanged. After completion of the calculation, the results were exported.

In the Mesh module, the seed function is used to specify the grid density. The model with the seed size of 10 mm is divided into 4500 units and the unit type is Heat Transfer, and the concrete mesh division is shown in Fig. 12 .The parameters of the static load and fatigue simulation test parts correspond to the test part.

In the Mesh module, the seeding function was used to specify the mesh density. The model with a seeding size of 10 mm was divided into 4500 elements, with the element type set to Heat Transfer. The detailed mesh division is shown in Fig. 12. Static load and fatigue simulation parameters matched the experimental specimen’s.

Results and discussion

Double shear test results

Under fatigue loading, the interface exhibited no significant changes during the initial loading phase. As fatigue cycles increased, the interface at the loading end exhibited minor displacements; then the displacement increased continuously and propagated toward the free end. In the late loading phase, the interface failed suddenly when the remaining part could not withstand the maximum fatigue load. Test results arein Table 6, and the failure mode in Fig. 13.

As observed from the failure mode in Fig. 13, the initial failure occurred at the interface between the adhesive layer and concrete, followed by gradual propagation of the debonding surface toward the concrete substrate. With increasing freeze-thaw cycles, freeze-thaw damage propagated from the concrete surface to the inner matrix, characterized by the gradual thinning of concrete layer debonded by the adhesive layer. Specimens subjected to more freeze-thaw cycles exhibited more rapid debonding damage.

For specimens with 0 freeze-thaw cycles, the thickness of the concrete layer debonded from the adhesive layer was approximately 3 mm, which could be considered an integral structure, so the fatigue life was relatively high. Due to fatigue, the bonded concrete layer became uneven, with coarse aggregates visible on the fracture surface. For specimens with 100 freeze-thaw cycles, partial concrete surface damageboccurred, which caused partial surface deterioration and thinning of the concrete layer debonded from the adhesive layer, with only partial surface bonding remaining between the adhesive layer and concrete particles. For specimens with 200 freeze-thaw cycles, the concrete surface had been completely damaged by freeze-thaw cycling, and damage had initiated propagation into the concrete matrix. Fatigue debonding damage occurred primarily on the concrete surface with no further propagation into the matrix; damage propagation was extremely rapid, and the fatigue life was significantly lower than that of the non-frozen-thawed specimens.

Figure 14 shows the strain distribution curves of BFRP under different fatigue cycles for the three groups of fatigue specimens, where di means the distance from the measurement point to the free end.

As observed in Fig. 14, the strain at the loading end reaches its maximum value. This is because the loading end is first subjected to the maximum fatigue load Pmax causing a rapid increase in strain. Subsequently, the loading end is no longer subjected to higher loads, resulting in only minor strain fluctuations under cyclic loading. At this stage, the fatigue load has not propagated to the second half of the interface; thus, strain changes are confined to the first half of the interface, while the second half remains relatively unchanged. With increasing fatigue cycles, the fatigue load gradually propagates along the interface toward the free end, leading to a rapid increase in strain at the middle measurement points. Owing to minimal damage accumulation in the middle region, the strain here exhibits significant growth potential. In the late loading stage, although the load propagates to the free end, continuous fatigue damage accumulation causes the strain at free end measurement points to gradually decrease and approach zero.The maximum strain at the loading end for specimens with 100 freeze-thaw cycles decreased by 3.74% compared to non-frozen-thawed specimens, and by 25.08% for 200 freeze-thaw cycles. In addition to the reduction in loading end strain with increasing freeze-thaw cycles, the strain variation range at the middle measurement points also diminished. This is because freeze-thaw cycling accelerates interface debonding, thus limiting concrete deformation and reducing strain growth.

Based on the strain difference and distance between adjacent points along the BFRP cloth, the shear stress is calculated. A dx segment is selected on the BFRP cloth to establish the force balance equation, with the elastic modulus introduced to derive Eq. (2). Using Eq. (2), the shear stress distribution curve for each specimen can be obtained.

Τf, σf are εf are the shear stress, tensile stress, and tensile strain of the BFRP cloth, respectively; Ef, tf are the elastic modulus and thickness of the BFRP cloth, respectively; Δε and Δx are the strain difference and distance between adjacent measurement points, respectively. Figure 15 shows the shear stress distribution of each specimen.

From the analysis of the shear stress distribution diagram in Fig. 15, the maximum shear stress values are predominantly distributed at di = 30. This is because, in the early stage of fatigue loading, no damage has yet occurred near the loading end, so the shear stress generally reaches its maximum after a small number of fatigue cycles. Furthermore, even higher peak shear stress values may be generated during the shear stress transmission process toward the far end. In the latter half of the interface, due to the accumulation of fatigue damage, both the shear stress values and the emerging peak values gradually decrease, which corresponds to the observed strain distribution. The shear stress in the first half of the interface decreases with the increase in the number of fatigue cycles, while the latter half of the interface exhibits the opposite trend. As fatigue loading continues to propagate toward the rear end, the shear stress in the latter half of the interface begins to increase with increasing number of fatigue cycles until a peak value appears in the latter half, which indicates that the interface is approaching complete failure.

The shear stress distribution of 0 freeze-thaw cycles exhibited three distinct peaks, with a maximum value of 4.2 MPa, and the peaks value were similar. This indicates that under fatigue loading, shear stress is transmitted sequentially as interface delamination progresses, with only minor shear stress loss. As the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases, the overall shear stress value of 100 freeze-thaw cycles decreases. At this stage, the three shear stress peaks remain relatively distinct, with a maximum peak of 3.7 MPa, corresponding to an 11.9% loss compared to 0 freeze-thaw cycle group. However, under freeze-thaw conditions, the two shear stress peaks in the latter half of the interface differed significantly from those in the first half. After 200 freeze-thaw cycles, severe shear stress loss occurred, and the interface shear stress distribution exhibited only one peak in the first half, with a value of 2.35 MPa. Compared to the 0 freeze-thaw cycles, the difference was significant, and the overall distribution showed a gradually decreasing trend from the loading end to the free end. Relative to the unfrozen condition, the total shear stress loss reached approximately 46.86%.

Finite element analysis results

The finite element simulation results are presented in Table 7.

The simulated fatigue test environment is much better than the test environment, but the overall trend is the same as the test value. Due to the large fatigue life, Fig. 16 shows the strain curve for the different fatigue number ratios under the simulation. Based on the results, the simulated limit load of the static load specimen is slightly lower than the experimental value. In contrast, the simulated fatigue life is significantly longer than the experimental value, which is primarily because fatigue loading in simulations is less complex than actual static loading, and the simulated fatigue environment is more idealized compared to the experimental environment. Nevertheless, the overall simulation trend is consistent with the experimental data. Due to the considerably long fatigue life, Fig. 16 shows the strain curves for different fatigue cycle ratios under simulation conditions.

The shear stress is calculated using Eq. (2), as shown in Fig. 17.

As observed in Figs. 16 and 17, the simulated stress-strain curves are in good agreement with the evolution trend of the experimental curves. Strain generally reaches its maximum value at the initial loading stage and then decreases toward the free end; additionally, the overall strain value decreases after freeze-thaw cycling. Compared with the 0 freeze-thaw cycle group, the test interface subjected to 200 freeze-thaw cycles exhibits a significant reduction in overall shear stress, with a decrease of approximately 36.11%, indicating severe interface damage after 200 freeze-thaw cycles.

Fatigue life forecast model

In this study, the S-N curve method was used to predict fatigue life. Although the method does not comprehensively explain many parameters, it can effectively describe the relationship between fatigue load and interface fatigue life. The curve expression mainly includes two forms: power function and exponential function40. For the power function form, the Equation is:

In Eq. (3), m and C are the parameters related to material performance, loading mode and stress ratio, which are determined by test. For Eq. (3):

By fitting the data in Table 6, the two parameters lgC=-0.7996 and m=-1.7037 can be obtained. Put these parameters into Eq. (4), the test equation is:

Similarly, the simulated S-N equation is obtained by using the above procedure:

Figures 18, 19 are the fitted curves.

The above two figures show that the stress amplitude exhibits a good linear relationship with fatigue life in the S-N curves under freeze-thaw cycling. As the number of freeze-thaw cycles increases, the stress amplitude decreases, and the fatigue life also decreases. However, numerous studies have demonstrated that the fatigue life of FRP-concrete interface increases with decreasing stress amplitude under non-freeze-thaw conditions. These results indicate that for specimens subjected to different freeze-thaw cycles, the effect of increasing freeze-thaw cycles on specimen fatigue life is far greater than the effect of stress amplitude reduction.

Conclusions

In this work, basalt fiber-reinforced composite (BFRP) was introduced into concrete reinforcement technology, and the fatigue characteristics of BFRP concrete under freeze-thaw cycles were evaluated through the double shear test and finite element analysis. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1)Fatigue tests indicate that debonding failure initially occurs at the interface between the adhesive layer and concrete, and subsequently, the debonded region gradually propagates into the concrete matrix. Increasing freeze-thaw cycles cause freeze-thaw damage to propagate from the concrete surface toward the matrix interior, reducing concrete surface density and gradually weakening the bonding strength of the concrete beneath the adhesive layer.

(2)The stress-strain curves show that strain is mainly concentrated at the loading end, and for specimens subjected to freeze-thaw cycling, the strain variation range in the middle part of the measurement points is reduced, indicating that the concrete surface after freeze-thaw cannot withstand large strain changes. After 200 freeze-thaw cycles, the overall interfacial shear stress decreased by approximately 46.86%.

(3)Finite element simulations show that the simulated stress-strain curves exhibit the same evolution trend as the experimental curves. After 200 freeze-thaw cycles, the overall shear stress loss is approximately 36.11%, indicating severe interfacial damage after 200 freeze-thaw cycles.

(4)The S-N curves from the tests and finite element simulations show that the interfacial fatigue life under freeze-thaw conditions still decreases as the stress amplitude decreases, indicating that the adverse effect of freeze-thaw cycling on fatigue life is much greater than that of stress amplitude reduction.

In this study, for computational convenience, the ABAQUS model was simplified based on actual working conditions: concrete was treated as a single-phase homogeneous material, the influence of freeze-thaw action on epoxy resin and BFRP materials was ignored, and a simplified material constitutive model was adopted. Although these simplifications were made based on rational considerations, result errors are still unavoidable. In future work, the model can be further refined in numerical analyses.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Lei Bin, L. Yan Yusong.Progress on concrete fatigue mechanism. Silicate Bull. 33 (8), 1978–1983 (2014).

Yang & Yongxin Yue Qingrui.Development and prospect of FRP reinforcement structure technology in China. The proceedings of the 20th National FRP/Composites Academic Exchange Conference and 40 Years of Review and prospect of Academic Development 253–258 (2014).

Liping, Y. & Feng P. Application and development of FRP in engineering structures. J. Civil Eng. 39(03), 24–36. (2006).

Yan Zewei. Research progress of the reinforcement technology of concrete slab. Shanxi Archit. 45 (13), 37–39 (2019).

Jinsheng, Y. & Wang H. Technology and application of CFRP. Fiber Compos. 23(02), 47–50 (2006).

Teng & Jinguang FRP Reinforced Concrete Structure (China State Construction Industry, 2005).

Shi Q. Development and application of continuous basalt fiber abroad. Glass Fiber. 34(04), 27–31 (2003).

OuYang, W. P. & Zhang, Y. Calculation and analysis of flexural and shear capacity of reinforced concrete beams strengthened by basalt fiber cloth. Industrial Constr. 37(06), 24–27 (2007).

Powers, T. C.A working hypothesis for further studies of Frost resistance of concrete. J. Am. Concrete Inst. 16 (4), 245–272 (1945).

Powers, T. C. The air requirement of frost-resistant concrete. Proceedings of the Highway Research Board Annual Meeting. Washington D.C., USA:[s.n.] 184–211 (1949).

Powers, T. C. & Helmuth, R. A. Theory of volume changes in hardened Portland cement pastes during freezing. Proceedings of the Highway Research Board Annual Meeting.Washington, D.C., USA:[s.n.] 285–297 (1953).

Powers, T. C. Freezing effects in concrete. Durability of Concrete, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, SP. 47(1), 1–10 (1975).

Litvan, G. G. Frost action in cement paste. Mater. Struct. 6 (4), 293–298 (1973).

Fgaerlund, G. Significance of Critical Degrees of Saturation at Freezing of Porous and Brittle materials. Durability of Concrete 13–65 (American Concrete Institute, 1975). ACI Special Publication.

Fagerlund, G. The critical degree of saturation method of assessing the freeze-thaw durability resistance of concrete. Mater. Struct. 10 (10), 58–66 (1977).

Chaoying Zou, J., Zhao, F., Liang Jianlin L. & Tianshui X.J. Degradation of mechanical properties of concrete caused by freeze thaw action. Building Struct. 29(01), 117–123 (2008).

Tang, G., Liu, X. & Shi, S. J. Evolution model of concrete failure surface under freeze-thaw conditions. Rock Mecha. Eng.25(12), 2572–2578 (2006).

Li, S. & Wang, B. Fatigue behavior of CFRP-concrete bonding interface under different thickness of adhesive layer. Transp. Sci. Eng. 30 (2), 51–54 (2014).

Tao Ma, J., Pan, H. & Wei Experimental study on CFRP-concrete bond performance under Cyclic load. Building Struct. 43 (19), 15–18 (2013).

Chou, J., Zhang, Z. & Zhang, J. Etc research on fatigue bonding performance of NSM CFRP concrete interface. Chin. J. Highways. 35 (02), 234–246 (2022).

Peng, H. et al. Experimental Investigation of Bond between Near-Surface-Mounted CFRP Strips and Concrete under Freeze-Thawing Cycling. Journal of Aerospace Engineering 32 (1), 4018125.1-4018125.10. (2019).

Carloni, C., Subramaniam, K. W., Savoia, M. & Mazzotti, C. Expermental determination of FRP-concrete cohesive interface properties under fatigue loading. Compos. Struct. 94 (4), 1288–1296 (2012).

Carloni, C. & Kolluru, V. Subramaniam.Inverstigation of sub-critical Gatigue crack growth in FRP-concrete cohesive interface using digital image analysis. Compos. Part. B:Engineering. 51, 35–43 (2013).

Yuan, J., Lin, J., Miao, Y. & Hou, X. The effect of bonding length on the bonding performance of AFRP concrete interface. Silicate Bull. 39 (09), 2830–2836 (2020).

Tian Longqiang Research on the. Fatigue Performance of BFRP Concrete Interface Bond (Jilin Jianzhu University, 2019).

Yanchun Yun, Y. F. W. Durability of CFRP-concrete joints under freeze -thaw cycling. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 65 (3), (2010).

Yong Gao. Study on Bonding Behavior of FRP Reinforcement (Changsha University of Science and Technology, 2015).

Hui Peng, B., Wang, J. & Zhang (eds), etc. Study on bonding fatigue performance of CFRP-concrete interface. Test Mechanics 29 (2), 189 (2014).

Zhipeng, Z. Mechanical Analysis and Experimental Study on Bonding Interface of GFRP Bridge Panel (Southeast University, 2015).

Jianzhuang, X., Jie, L. & Jintao, W. Study on test methods for bond strength between fiber sheet and concrete. Fiber Reinforced Plastics/Composites. 29(3), 3–6 (2002).

Diab, H. M., Wu, Z. & Iwashita, K. Theoretical solution for fatigue debonding growth and fatigue life prediction of FRP-concrete interfaces. Adv. Struc Eng. 12 (6), 781–792 (2009).

Ferrier, E. et al. Fatigue reliability of extemal bonded CFRP used for concrete structure. Mater. Struct. 38 (275), 39–46 (2005).

Bizindavyi, L., Neale, K. W. & Erki, M. A. .Experimental investigation of bonded fiber reinforced polymer-concrete joints under Cyclic loading. J. Compos. Const. 7 (2), 127–134 (2003).

Carloni, C. & Subramaniam, K. V. .Investigation of sub-critical fatigue crack growth in FRP/concrete cohesive interface using digital image analysis. Compos. Part. B-Eng. 51, 35–43 (2013).

Leusmann, T. & Budelmann, H. Fatigue design concept for extermally bonded CFRP-Plates. In: Proc of 6th International Conference on FRP Composites in Civil Engineering (CICE 2012), Rome, Ltaly: International Institute for FRP in Construction(IIFC), 1-9 (2012).

Leusmann, T. & Budelmann, H. Bond capacity of externally CFRP-reinforced concrete structures under high cycle fatigue loads. In: Proceedings of 9th International Symposiun on FRP Reinforcement for Concrte Structures(FRPRCS-9) (eds Oehlers, D., Griffith, M., Seracino, R.) University of Adelaide 1. (Sydney, Australia, 2009).

Yunfeng Qiao. Damage Degradation and Life Prediction of Concrete with Different Saturation Levels Under the Coupling Effect of freeze-thaw and Fatigue (Southeast University, 2018).

]Dawa zhaxi. Study on the teaching practice of network course based on Midas civil software application - a case study of Bridge engineering. Comp. Stud. Cult. Innov. 4 (29), 143–145 (2020).

Zhengzhou Wu, A., Liu, S., Wang, Y. & Wang, F. The development of composite foundation and the finite element analysis application review. J. Shanxi Archit. 48 (02), 83–86 (2022).

Ning Huang. Research on the Fatigue Life Prediction Method of Large Structural Parts (Institute of Metallurgy, School of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Central South University, 2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Horizontal Research Projects on School-Enterprise Cooperation: Research on the Salt-Frost Resistance Durability of Composite Green Concrete in the Complex Soil Environment of Northeast Asia Permafrost Region (No. DJ-ZDXM-2023-35).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haoyue Sun :Responsible for drafting the initial manuscript, conducting experimental operations; Jiang Shen:carried out text proofreading and data verification; Xiaoping Su: performed data analysis; Yulong Sun:Data processing and analysis, thesis revision; Hao Jiang:conducted research on the experimental protocol; Zhaofa Cui : took charge of software operation; Xiaoxiao Yang:engaged in text revision; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, H., Shen, J., Su, X. et al. Fatigue characteristics and mechanical evaluation of basalt fiber reinforced composite material concrete under freeze-thaw cycles. Sci Rep 16, 1990 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31308-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31308-3