Abstract

Brain metastases (BMs) are frequent and devastating complications of systemic malignancies, necessitating accurate diagnosis and origin identification for effective treatment strategies. Invasive biopsies are currently required for definitive diagnosis, highlighting the need for less invasive diagnostic approaches and robust biomarkers. Circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) have demonstrated potential as sensitive and specific diagnostic biomarkers in various cancers. Thus, our objective was to identify and compare miRNA profiles in BM tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and plasma, with a specific focus on liquid biopsies for diagnostic purposes. Total RNA enriched for miRNAs was isolated from histopathologically confirmed BM tissues (n = 30), corresponding plasma samples (n = 30), and CSF samples (n = 27) obtained from patients with diverse BM types. Small RNA sequencing was employed for miRNA expression profiling. Significantly differentially expressed miRNAs were observed in BM tissues, enabling the differentiation of primary origins, particularly breast, colorectal, renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma metastases. The heterogeneity observed in lung carcinomas also manifested in the corresponding BMs, posing challenges in accurate discrimination from other BMs. While tissue-specific miRNA signatures exhibited the highest precision, our findings suggest low diagnostic potential of circulating miRNAs in CSF and blood plasma for BM patients. Our study represents the first analysis of miRNA expression/levels in a unique set of three biological materials (tissue, blood plasma, CSF) obtained from the same BM patients using small RNA sequencing. The presented results underscore the importance of investigating aberrant miRNA expression/levels in BMs and highlight the low diagnostic utility of circulating miRNAs in patients with BMs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brain metastases (BMs) represent a devastating complication of advanced cancer that affects approximately 30–40% of patients over the course of their illness. The increasing incidence of BMs can be attributed to several factors, such as advancements in cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment, resulting in longer survival of the patients. In turn, the extended overall survival conceivably increases the likelihood of developing BM over time. Furthermore, the availability of more sophisticated imaging techniques has enabled clinicians to detect metastatic tumors in the brain at earlier stages. Additionally, certain cancer types possess a greater propensity to metastasize to the brain, contributing to the upward trend of BMs incidence1,2. BMs frequently arise from lung, breast and renal cell carcinoma, and melanoma. These types of cancer have been identified as common origins of BMs possibly due to their high incidence rates and ability to spread beyond their primary sites, however, almost any cancer can metastasize to the brain, including colorectal cancer3. Also, primary site of cancer is not detected in up to 15% of BM patients4, and although sources vary slightly, they make up a non-negligible subgroup of BMs of unknown primary.

Due to the limitations of currently available methods, BM diagnostics remains challenging. Invasive procedures, such as tumor tissue biopsy, may not always be feasible or practical in all patients due to the location of the metastases or other clinical factors5. Besides, the accuracy of biopsy depends on the size and location of the metastasis and may not always provide a representative sample of the tumor. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new diagnostic methods that are less invasive and more reliable. Liquid biopsies, especially blood plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), have emerged as promising alternatives for the diagnosis of many diseases including brain metastases. Liquid biopsies are less invasive than biopsy and can provide real-time information about tumor development and progression. Moreover, they allow for repeated sampling over time, which is particularly relevant for monitoring treatment response and disease recurrence6.

Circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs that have been postulated as potential biomarkers providing valuable diagnostic and prognostic information for various diseases since they can be detected in body fluids. Several studies have investigated levels of miRNAs in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with brain tumors. For example, miR-21, which is known to promote tumor cell proliferation and invasion, has been shown to be elevated in the CSF of both brain metastasis and glioblastoma (GBM) patients compared to control samples7. A previous study investigated CSF miRNA profiles in brain tumor patients and suggested strong potential for these molecules as prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers8. Other findings outlined that certain miRNAs in the blood plasma have the potential to serve as new biomarkers for GBM and could be valuable in the clinical management of these patients. Specifically, plasma levels of miR-21, miR-128, and miR-342-3p were observed to be significantly altered in GBM patients compared to non-tumor controls9. Diagnostic potential of tissue miRNAs for brain metastases have been investigated recently10. Nevertheless, there is a need for further research to identify accurate and reliable biomarkers for the early detection of brain metastases. Comparing CSF and blood plasma, the former is considered to be a more suitable and cleaner option, as it is in direct contact with the brain and neural system and should reflect the actual tumor microenvironment. However, due to its invasiveness, its collection represents an additional burden for patients. On the other hand, circulating miRNAs in blood plasma tend to be more affected by various factors associated with preanalytical phase including hemolysis associated with highly abundant miR-16, or presence of erythroid-specific miRNAs, such as miR-486 or miR-45111,12, which can lead to the waste of sequencing capacity and biased data generation, and consequently can affect the accuracy of the diagnosis.

Our aim was to identify miRNA profiles in tumor tissue, blood plasma, and CSF from BM patients and compare them. For this purpose, we used a unique set of biological specimens from BM patients and investigated their suitability for diagnosis of the 5 most frequent types of BMs. Our results contribute to the research in the field of new diagnostic tools that would pose less burden than the currently used biopsy, and at the same time help to refine and accelerate the diagnosis of these patients in the future.

Materials and methods

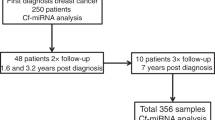

Patient samples

Native BM tissue and peripheral blood samples from each patient were collected by cooperating neurosurgical departments of University Hospital Brno and St. Anne’s University Hospital Brno (both Brno, Czech Republic). CSF was collected by the neurosurgical department of University Hospital Brno via lumbar puncture (L3–L4 or L4–L5) performed as part of the routine preoperative diagnostic work-up. Study aliquots were prepared from clinically indicated CSF without introducing any additional invasive procedure. Native BM tissue samples were collected during surgery as a part of the standard treatment protocol. Peripheral blood and CSF samples were collected for the purposes of diagnostics, and the aliquots were used for the study. The study and the informed consent form were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of University Hospital Brno under the code EKFNB-17-06-28-01. A signed informed consent form was obtained from each patient prior to the beginning of all procedures and the collection of patient tissue, peripheral blood, and CSF samples. The study methodologies obeyed the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. In total, 30 fresh tissue samples were collected for the study and immediately stored in RNAlater Stabilization Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 4 °C for 24 h after the collection and then frozen at –80 °C until further use. All tissue samples were histologically diagnosed according to the WHO 2021 classification scheme independently by two histopathologists. Peripheral blood samples collected for the study were centrifuged (2000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) immediately after collection to obtain blood plasma, which was separated, transferred to clean tubes, and then frozen at − 80 °C until further use. CSF samples collected for the study were immediately centrifuged (500 × g, 10 min, 4 °C) after the collection to separate higher-density particles and contaminants from the supernatant, which was then transferred to new tubes and frozen at − 80 °C until further use.

Primary CRC and healthy non-oncological control blood plasma samples were collected at the University Hospital Brno within the previous projects approved by Research Ethics Committee of University Hospital Brno under reference numbers EKFNB-15-06-10-03 on June 10, 2015, and EKFNB-15-05-13-01 on May 13, 2015, respectively. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. Peripheral blood samples were collected before surgery and initiation of any treatment in CRC patients; similarly, peripheral blood samples were collected prior to any procedure or treatment that could affect miRNA levels in healthy non-oncological donors. Peripheral blood was processed for plasma within one hour after extraction. Plasma was obtained by centrifugation at 1,200 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. To complete the removal of residual cellular components, plasma samples were re-centrifuged at 12,000 × g for a further 10 min at 4 °C. Finally, plasma samples were stored at − 80 °C.

RNA isolation and purification

Total RNA enriched for small RNA species from fresh-frozen tissue samples was isolated using mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol as described in detail earlier10. After thawing plasma samples on ice, 250 µl of the sample were transferred to a clean tube and centrifuged (1000 × g, 5 min, 4 °C). Subsequently, 200 µl of supernatant were used for isolation of total RNA enriched for small RNA species using the miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After thawing CSF on ice, 1 ml of sample was used for isolation and purification of total RNA enriched for small RNA species using the Urine microRNA Purification Kit (Norgen Biotek Corp., ON, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified RNA was then frozen at − 80 °C until further use.

Nucleic acid quantity and quality control

Nucleic acid quantity and quality control were conducted as described in detail earlier10. Low concentrations of RNA isolated from liquid biopsies could not be measured by standard spectrophotometry or fluorometry, therefore, maximum volume was used as the input for the cDNA library preparation as recommended in the manufacturer’s protocol.

Library preparation, pooling, and sequencing

Small RNA libraries were constructed from 30 total RNA samples from tissue, 30 from plasma and 27 from CSF using QIAseq miRNA Library Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA input was 100 ng for tissue and 5 µl for plasma and CSF. The preparation and cDNA libraries quantity and quality control were described in detail earlier10. Subsequently, libraries were normalized and pooled in equimolar ratio using online weight to molar quantity converter. Library pools (24 libraries in each pool) were then processed according to the NextSeq System Denature and Dilute Libraries Guide13. Denatured and diluted PhiX Control v3 was added at 1% to all pools as an internal standard and single-read sequencing with 75 bp read length was performed using NextSeq 500 Sequencing System and NextSeq 500/550 High Output v2 kit (75 cycles) (all Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Approximately 16.7 M sequencing reads per library were expected.

Processing of small RNA sequencing data

The pre-alignment quality control (QC) of the sequencing data was performed using FastQC (version 0.11.9)14. Adapter sequences were trimmed with cutadapt (version 3.3)15, and reads were collapsed with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) using the FASTX-Toolkit (version 0.0.14)16. Subsequently, quality trimming was done using cutadapt and reads shorter than 15 bp were removed from the dataset. The remaining reads were mapped against the miRBase database (version 21)17 using the miraligner tool (version 3.2)18. All generated numerical and graphical output from QC was gathered in cohesive reports via MultiQC (version 1.7)19. All statistical analyses were performed in the R environment (version 4.0.4). Differential expression analysis was carried out using the Bioconductor (version 3.11) package DESeq2 (version 1.30.1)20.

Multiple comparisons were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Unsupervised clustering was carried out with the complete linkage method (farthest neighbor) and Manhattan distance measure. Results were visualized as heatmaps with dendrograms, bar plots, and PCA plots.

For functional interpretation, experimentally validated target genes of significantly upregulated and downregulated miRNAs were retrieved from miRTarBase via the multiMiR package (version 1.30.0). Target gene sets were analyzed separately for up- and downregulated miRNAs using over-representation analysis (ORA) implemented in clusterProfiler (version 4.17.0)21, enabling identification of enriched and depleted biological processes and signaling pathways. Multiple testing correction was again performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

Results

A subset of microRNAs is highly expressed in tissues and present in high levels in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid samples of patients with brain metastasis

We successfully performed small RNA sequencing on 30 tissue, 30 plasma, and 27 CSF samples of BM patients and generated ~ 1.7 billion reads (16.9 ± 2.5 million per tissue sample, 21 ± 3.0 million per CSF sample, and 21 ± 4.2 million per plasma sample). Using miraligner, we identified 34.2 ± 9.2% of tissue sample reads, 6.8 ± 8.3% of plasma sample reads, and 1.9 ± 2.2% of CSF sample reads as miRNAs (Supplement 1). Bioinformatics analysis indicated fewer mapped miRNA reads in liquid biopsies. Moreover, we compared the highly abundant miRNAs in all samples (Fig. 1a), as well as in tissue (Fig. 1b), CSF (Fig. 1c), and plasma (Fig. 1d) samples separately. Highly expressed miRNAs/high miRNA levels were similar across all types of biopsies, with hsa-miR-16-5p and hsa-miR-21-5p being the most frequently observed. Plasma samples showed significant contamination of erythropoietic miR-486-5p, which was also present in CSF and tissue samples but at lower levels. In addition to lower miR-486-5p contamination, tissue samples had lower overall percentage of highly expressed miRNAs (~ 21% for 2 most expressed miRNAs) compared to plasma (~ 36%) and CSF samples (~ 23%).

MiRNA expression profiles are origin-specific for tissue samples of patients with brain metastasis

We compared miRNA expression profiles in tissue samples of patients with BM and using the likelihood ratio test identified 386 miRNAs (Supplement 2) with adjusted p-value < 0.05, log2 fold change (FC) |log2FC|≥ 0.585. This significance threshold was consistently applied across all subsequent tissue analyses. Top 20 miRNAs generated by this analysis displayed discriminatory capacity with relatively high sensitivity and specificity (Tab. 1).

Analysis of tissue samples from BM patients revealed a markedly higher ability to discriminate metastatic origin based on miRNA profiles compared to plasma or CSF (Fig. 2a). The likelihood ratio test identified 386 miRNAs with adjusted p-value < 0.05 across all tumor types, which were used as the basis for subsequent comparisons. When focusing on the most significant features, the top 20 deregulated miRNAs across all groups showed clear clustering patterns (Fig. 2b). Differential expression analysis of the 10 pairwise contrasts (adjusted p-value < 0.05, |log2FC|≥ 0.585) revealed extensive differences between tumor origins, with each comparison yielding between 70 and 224 deregulated miRNAs (Fig. 2c–l). For instance, large sets of deregulated molecules were observed in BMM vs BMC (n = 224), BMC vs BML (n = 223), and BMB vs BML (n = 178). Even the least distinct contrast (BMM vs BML) still resulted in 70 deregulated miRNAs. All miRNAs that showed significant differential expression can be found in Supplement 2.

Heatmaps with unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on the tissue miRNA levels: (a) 386 unique miRNAs with padj < 0.05 derived from the likelihood ratio test; (b) top 20 most significant miRNAs across all tumor origins (padj < 0.05); (c) 99 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing colorectal carcinoma brain metastases (BMC) from breast carcinoma brain metastases (BMB); (d) 178 deregulated miRNAs differentiating non-small cell lung carcinoma brain metastases (BML) from BMB; (e) 161 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing BMB from melanoma brain metastases (BMM); (f) 85 deregulated miRNAs differentiating renal cell carcinoma brain metastases (BMR) from BMB; (g) 223 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing BMC from BML; (h) 224 deregulated miRNAs differentiating BMM from BMC; (i) 181 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing BMC from BMR; (j) 116 deregulated miRNAs differentiating BMM from BMR; (k) 89 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing BMR from BML; (l) 70 deregulated miRNAs differentiating BMM from BML, (padj < 0.05, |log2FC|≥ 0.585 for all comparisons in panels (b–l).

MiRNA level profiles do not show significant specificity in CSF samples of patients with brain metastases

Next, we compared miRNA levels in CSF samples from 27 patients with BMs originating in the 5 most frequent primary tumor types (Fig. 3a) and found that we could distinguish one type of BM from other BMs based on origin-specific miRNAs only to a limited extent. The likelihood ratio test uncovered four miRNAs (miR-1281, miR-138-5p, miR-205-5p, miR-211-5p) with adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log2FC|≥ 0.585. We also refer to this cut-off value of significance level in all subsequent comparisons in CSF samples.

Heatmaps with unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) miRNA levels: (a) 53 unique miRNAs with p-value < 0.05 derived from the likelihood ratio test; (b) 7 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing melanoma brain metastases (BMM) from breast carcinoma brain metastases (BMB); (c) 5 deregulated miRNAs differentiating BMM from renal cell carcinoma brain metastases (BMR); (d) 2 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing colorectal carcinoma brain metastases (BMC) from BMB, (padj < 0.05, |log2FC|≥ 0.585 for all comparisons in panels (b–d).

DE analysis was performed to further investigate potential differences between the analyzed BM types. The highest count of significantly deregulated miRNAs (n = 7) was found in the comparison of BMM vs BMB, with 3 present in high and 4 in low levels (Fig. 3b). Significant differences (5 miRNAs) were also observed when contrasting BMM and BMR, where we observed 2 upregulated and 3 downregulated miRNAs (Fig. 3c) In the case of contrast of BMC and BMB high levels of miR-135b-5p and low levels of miR-1307-5p were detected (Fig. 3d). Higher level of miR-135b-5p was also observed in BML vs BMB and BMR vs BMB (Supplement 2).

Among the common differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs detected across biopsy types, we identified concordant upregulation of miR-211-5p and downregulation of miR-145-5p in CSF and tissue samples in the comparison of BMM and BMB (Fig. 4).

MiRNA level profiles do not show significant specificity in blood plasma samples of patients with brain metastases

Analysis of blood plasma samples from 30 BM patients revealed only limited ability to distinguish metastatic origin based on miRNA profiles (Fig. 5a). The likelihood ratio test identified four miRNAs (hsa-miR-320c, hsa-miR-320d, hsa-miR-423-3p, and hsa-miR-548j-5p) with adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log2FC|≥ 0.585. This cut-off of significance level was used for all other comparisons of plasma samples. Differential expression analysis across all ten pairwise comparisons showed the highest number of deregulated miRNAs in the contrast between BMC and BMR (n = 13), whereas smaller sets of deregulated molecules were observed in BMC vs BML (n = 3), BMB vs BMR (n = 3), BMB vs BML (n = 2), and BMM vs BML (n = 2) (Fig. 5b–f). These differences, however, were inconsistent and did not provide strong discriminatory signatures for plasma samples.

Heatmaps with unsupervised hierarchical clustering based on the blood plasma miRNA levels: (a) 40 unique miRNAs with p-value < 0.05 derived from the likelihood ratio test; (b) 13 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing colorectal carcinoma brain metastases (BMC) from renal cell carcinoma brain metastases (BMR); (c) 3 deregulated miRNAs differentiating BMC from non-small cell lung carcinoma brain metastases (BML); (d) 3 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing brain carcinoma brain metastases (BMB) from BMR; (e) 2 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing BMB from BML; (f) 2 deregulated miRNAs distinguishing melanoma brain metastases (BMM) from BML (padj < 0.05, |log2FC|≥ 0.585 for all comparisons in panels (b–f).

When comparing common DE miRNAs across biopsy types, partial concordance was observed between plasma and tissue. Upregulation of hsa-miR-320d and hsa-miR-320c was consistently detected in both sample types when contrasting BMC and BML. In the BMC vs BMR comparison, plasma and tissue showed upregulation of hsa-miR-320c, hsa-miR-320d, and hsa-miR-320e, together with downregulation of hsa-miR-144-3p. Interestingly, in this comparison we also detected opposite regulation of hsa-miR-19a-3p, which was upregulated in tissue but downregulated in plasma. Concordant upregulation of hsa-miR-455-3p was observed in both plasma and tissue in the BMR vs BML comparison (Fig. 6). Moreover, cross-material concordance was evident also in other biopsy types, as we found common upregulation of hsa-miR-211-5p and downregulation of hsa-miR-145-5p in BMM vs BMB in tissue and CSF samples (Fig. 4).

Volcano plots depicting differentially expressed (DE) miRNAs common to both plasma and tissue samples with < 0.05: (a) concordant upregulation of miR-320c and miR-320d was observed in the comparison of colorectal (BMC) and lung carcinoma metastases (BML); (b) upregulation of miR-320c, miR-320d, and miR-320e together with downregulation of miR-144-3p in the comparison of BMC and renal cell carcinoma metastases (BMR), and (c) upregulation of miR-455-3p in the comparison of BMR and BML.

Analysis of blood plasma samples from patients with brain metastasis, colorectal carcinoma, and healthy controls reveals similarities between primary tumor and metastasis

To determine whether plasma miRNA levels in BM patients of colorectal origin are influenced by the primary tumor, we performed a differential analysis of plasma samples from BMC patients, primary CRC patients, and healthy controls. Principal component analysis (PCA) including all metastatic plasma samples together with primary CRC and healthy controls did not show clear separation of the groups. However, when restricting the analysis to BMC, primary CRC, and healthy plasma, a closer similarity between BMC and CRC became evident, with both groups clustering apart from healthy controls (Fig. 7). Consistently, 42% of significantly deregulated miRNAs (adjusted p-value < 0.05, |log2FC|≥ 0.585,) overlapped between the CRC vs. healthy and BMC vs. healthy contrasts (Supplement 3).

PCA plot showing a: (a) comparison of plasma samples from healthy controls, patients with primary colorectal carcinoma (CRC) and patients with brain metastasis derived from colorectal carcinoma (BMC); (b) comparison of plasma samples from healthy controls and patients with primary CRC, BMC, BM from breast carcinoma (BMB), BM from non-small cell lung carcinoma (BML), BM from melanoma (BMM), and BM from renal clear cell carcinoma (BMR).

Functional enrichment analysis of deregulated miRNAs reveals associations with key signaling pathways in the brain

Over-representation analysis (ORA) of target genes was performed separately for depleted miRNAs (upregulated targets) and enriched miRNAs (downregulated targets) using adjusted p-value < 0.01 and fold enrichment ≥ 1.5 as cut-offs. We performed enrichment analysis on all types of biopsies; however, only tissue samples have a sufficient amount of significant miRNAs to perform gene target analysis and the following ORA. The observed pathway enrichment could reflect miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation. Because the input consists of miRNA target genes, overlapping pathway enrichment may reflect the broad regulatory reach of miRNAs rather than uniform pathway activation or repression.

The most frequently represented Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes across diagnoses were associated with cell cycle regulation (including mitotic cell cycle phase transition, mitotic nuclear division, and regulation of cell cycle phase transition) and RNA-related processes (such as cytoplasmic translation and miRNA metabolic process).

KEGG enrichment22,23,24 revealed broad involvement of tumor-suppressor and growth-regulatory pathways. Genes regulating cell cycle, DNA replication, p53 signaling, mismatch repair, apoptosis, and senescence were significantly enriched, indicating impaired genomic stability and apoptotic control. Several receptor signaling and therapy-resistance pathways (EGFR, ErbB, endocrine and platinum resistance, PD-L1/PD-1) were also highlighted, suggesting potential alterations in proliferation and drug response. Disease-specific cancer pathways further reflect the impact of these dysregulated processes in multiple tumor types.

Reactome enrichment highlights dysregulation of cell cycle checkpoints (RB1, TP53), suppression of apoptosis, aberrant growth factor signaling, compromised DNA repair, transcriptional reprogramming, and cytoskeletal/nuclear architecture alterations, suggesting coordinated disruption of tumor suppressor, proliferative, and lineage-specific pathways.

In breast carcinoma brain metastases, the dominant categories were related to translation and cell cycle control. Colorectal carcinoma brain metastases showed the most significant enrichment of cell cycle–associated terms. Lung carcinoma brain metastases were characterized by enrichment of miRNA processing and transcription-related processes. Melanoma brain metastases displayed enrichment of cell cycle regulation and nucleocytoplasmic transport. Renal cell carcinoma brain metastases showed significant enrichment in miRNA regulation–related categories.

The top 5 downregulated and upregulated GO biological processes for each diagnosis are summarized in Fig. 8, while the complete results of the ORA analysis are provided in Supplements 4–8.

Top 5 downregulated and upregulated Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes identified by over-representation analysis (ORA) for each diagnosis compared to the rest of the cohort: (a) breast carcinoma, (b) colorectal carcinoma, (c) non-small cell lung carcinoma, (d) melanoma, and (e) renal clear cell carcinoma brain metastases. Cut-off: padj < 0.01, fold enrichment ≥ 1.5. Bars represent statistical significance (± log10(padj)).

Discussion

BMs are a frequent complication of advanced solid cancers and are associated with poor prognosis. The incidence of BMs has risen, possibly due to improved diagnostics and therapy methods that extend patient survival but also provide more opportunities for cancer cells to metastasize to the brain. Despite therapeutic and imaging advances, outcomes remain suboptimal. Accurate and early diagnosis of the BM origin is crucial for tailoring adequate therapy to improve patients’ prognosis. When lesions are surgically risky or inaccessible, establishing whether a lesion represents a BM and identifying its primary can be challenging; even state-of-the-art imaging may be non-specific25,26. These considerations motivate the search for minimally invasive molecular biomarkers—ideally obtainable from liquid biopsies—to support precise BM diagnosis.

The aim of our study was to identify specific miRNA patterns in tissue, CSF, and blood plasma of BM patients, to compare these materials with respect to their suitability for early diagnosis, and to evaluate whether a less invasive approach than tissue biopsy could accurately determine BM origin. Such a tool would allow treatment planning at an earlier stage and potentially improve patients’ quality of life. Because tissue-derived miRNAs have previously been shown to classify BMs with high accuracy, we hypothesized that CSF could provide an even better diagnostic source. CSF is unique to the central nervous system (CNS), have been proven to preserve miRNAs in a stable form, and is in direct contact with the tumor environment10. Unlike plasma, which reflects systemic processes and is more prone to contamination, CSF should contain fewer non-specific miRNAs and thus better represent tumor-derived molecular signals8.

Based on our results, tissue-derived miRNAs profiles were able to discriminate between the analyzed BM origins with sensitivities ranging from 66.7 to 100.0% and specificity from 91.7 to 100.0% (Table 1). The lowest sensitivity was observed in BML, likely reflecting the known histological heterogeneity of non-small cell lung carcinoma metastases27. These findings and identified miRNA profiles are consistent with the results of Roskova et al.10. However, tissue biopsy and subsequent histopathological examination are not always feasilible due to the fragility of cancer patients, the high invasiveness of the surgical procedure, or the BM anatomical localization. To address these limitations, we extended our analyses to 2 liquid biopsy sources – CSF and plasma – which are both less invasive to obtain than tissue. From biochemical perspective, miRNAs possess favorable properties that make them ideal biomarker candidates. These small transcripts exhibit high stability and have a prolonged half-life in biological samples, thereby eliminating the need for specialized handling. Moreover, miRNA analysis can be applied to readily available samples and quantified using standard techniques already employed in clinical laboratories, such as qPCR, at relatively low cost with high analytical sensitivity and specificity. Nevertheless, the identification of new circulating miRNA biomarkers is challenging due to multiple factors.

The profiling of circulating miRNAs in peripheral blood has attracted significant attention as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for various diseases. However, the presence of highly abundant, non-specific miRNAs in peripheral blood, particularly miR-16-5p and miR-486-5p from the erythroid-specific group, complicates data interpretation and may mask tumor-derived signals. Comparison of the potential use of serum instead of plasma for translational studies was performed by Dufourd et al., however, non-specific miRNAs were present at similar levels in both materials, and, in addition, plasma performed better with respect to overall sequencing data yield28. Consistent with this, our plasma libraries were markedly affected by erythroid contamination (Fig. 1), leading to reduced complexity and limiting the detection of low-abundance miRNAs12,29.

When comparing biological materials, plasma displayed a higher number of differentially expressed miRNAs overlapping with tissue, as shown in volcano plots (Figs. 4, 6). These included concordant deregulations of the miR-320 family, miR-144-3p, and miR-455-3p across specific tumor-type contrasts. In contrast, CSF samples exhibited fewer overlaps with tissue, with consistent signals limited mainly to miR-211-5p and miR-145-5p in melanoma versus breast metastases. This suggests that while CSF better reflects the intracranial microenvironment and is less influenced by systemic processes, the overall detectable signal is weaker than in plasma.

Overall, CSF remains the biologically more specific fluid, but its limited number of deregulated miRNAs constrains diagnostic applicability. Plasma, despite being more heavily contaminated, captured more tumor-tissue overlaps, yet the reproducibility and robustness of these signals remain insufficient for clinical use. These findings highlight the complexity of liquid biopsy–based miRNA profiling, where both biological proximity and technical background strongly influence the diagnostic potential.

Heatmap-based clustering further illustrated the differences in classification performance between tissue and liquid biopsies. Tissue samples showed robust separation of BM origins, with hundreds of deregulated miRNAs identified in each pairwise comparison (Fig. 2). In contrast, CSF samples revealed only small sets of deregulated miRNAs, with the largest difference observed between melanoma and breast metastases (n = 7), and fewer changes in other comparisons such as melanoma vs. renal or colorectal vs. breast (Fig. 3). These results highlight the limited discriminatory capacity of CSF, despite its proximity to the tumor microenvironment. Plasma samples yielded somewhat larger sets of deregulated miRNAs in certain contrasts—for example, 13 molecules in colorectal vs. renal metastases—yet the overall profiles remained inconsistent and did not allow for reproducible classification (Fig. 5).

Although previous work demonstrated that CSF miRNA profiles can distinguish between primary brain tumors8, we could not confirm comparable diagnostic performance in the context of BMs. While some classification ability was evident in CSF when broader miRNA sets were used, this signal is unlikely to translate into a clinically feasible panel limited to a small number of molecules. Plasma, on the other hand, showed more overlaps with tissue but was substantially affected by contamination and variability, reducing its clinical utility. Overall, our data suggest that neither CSF nor plasma miRNA profiles, as currently assessed, provide the robustness necessary for origin-specific BM diagnosis. These findings underscore the challenges of applying liquid biopsies for this purpose and emphasize the need for validation in larger, balanced cohorts.

We further explored whether plasma miRNA profiles in BM patients of colorectal origin reflect the metastatic process itself or are primarily influenced by the molecular signature of the primary tumor. Differential analysis revealed that plasma from colorectal BM patients clustered more closely with plasma from primary CRC patients than with healthy controls, with one-third of significantly deregulated miRNAs shared between both comparisons (CRC vs. healthy and BMC vs. healthy; Fig. 7, Supplement 3). This observation indicates that circulating miRNA signals in plasma are strongly driven by the primary tumor and cannot reliably distinguish between colorectal primaries and their brain metastases. Consequently, small RNA sequencing of plasma appears unsuitable as a stand-alone diagnostic tool in this setting.

A potential caveat of this comparison is the possibility of technical batch effects, since CRC and healthy plasma libraries were prepared and sequenced separately from BM plasma libraries, and some aliquots underwent longer storage prior to sequencing. Although identical protocols and QC thresholds were applied, cross-run variation cannot be entirely excluded and may contribute to the observed clustering. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted qualitatively, as an indication of strong overlap between plasma miRNA signals from colorectal primaries and corresponding brain metastases. Comparable analyses in CSF were not feasible in the present study due to limited material, but could provide valuable insights in future work.

To further contextualize the observed deregulation, we performed target-based over-representation analyses (ORA) on tissue-derived miRNAs. While the breadth of deregulated miRNAs in CSF and plasma was insufficient for robust enrichment, tissue profiles revealed consistent association with pathways known to be central in metastatic biology. Across diagnoses, GO terms were dominated by cell cycle control and RNA-related processes, whereas KEGG enrichment highlighted p53 signaling, DNA replication and repair, apoptosis, and receptor tyrosine kinase signaling such as EGFR/ErbB. Similar enrichment patterns have been described in metastatic cascades, where cell cycle deregulation, impaired apoptosis, and growth factor receptor signaling act as hallmarks of progression and treatment resistance30,31. Reactome results converged on disruption of checkpoint regulation, growth factor signaling, and transcriptional reprogramming. These patterns reflect canonical hallmarks of metastasis, supporting the biological relevance of the identified tissue miRNA signatures.

Diagnosis-specific differences were also observed, with breast and colorectal BMs enriched for translation and cell cycle processes, lung BMs showing signatures related to miRNA processing, melanoma BMs highlighting nucleocytoplasmic transport, and renal BMs enriched in miRNA regulation–related terms. This indicates that, while BM share common proliferative and survival-related programs, lineage-specific regulatory features are preserved. Notably, immune-related enrichment such as PD-1/PD-L1 signaling was also identified, consistent with recent reports on the role of miRNAs in modulating immune checkpoint pathways32.

Nonetheless, functional annotation of miRNA targets has inherent limitations. ORA can be biased toward broadly annotated pathways such as cell cycle or p53, and does not necessarily distinguish direct causal regulation from broader network effects33,34. These findings should therefore be regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than definitive evidence of pathway activation. Future studies integrating miRNA with mRNA or proteomic data, or applying network-based approaches, will be needed to validate whether these pathway enrichments translate into functional consequences.

Recent advances in next-generation sequencing (NGS) have enabled comprehensive profiling of thousands of miRNAs across diverse biological materials, including plasma and CSF. Together with bioinformatic pipelines, NGS offers high-throughput opportunities for biomarker discovery, and circulating miRNAs with prognostic or predictive value could eventually support personalized management of BM patients. However, the field continues to face several major challenges.

First, the absence of standardized protocols for RNA extraction, library preparation, and data analysis complicates reproducibility and hampers the translation of candidate biomarkers into clinical use. This is particularly relevant for liquid biopsies, where RNA input is low and non-miRNA reads or adapter dimers frequently dominate sequencing libraries, thereby reducing the depth available for bona fide miRNAs. Technical variation between extraction kits and sequencing runs has been shown to markedly influence both the detection and relative abundance of individual miRNAs35. Achieving community consensus on pre-analytical handling and bioinformatic evaluation will be crucial before routine clinical application.

Second, circulating miRNA levels are influenced by multiple biological factors unrelated to tumor biology. Daily fluctuations, disease stage, and patient-specific attributes such as age, sex, diet, smoking status, or physical activity have all been reported to shape miRNA profiles36,37,38,39. This complexity makes cohort matching challenging, especially in rare conditions such as BM, where sample availability is inherently limited. While the long-term stability of miRNAs in frozen plasma is advantageous, quantitative declines over time have been documented40, underscoring the need for consistent sample handling and preferential use of recently collected material.

Third, methodological bottlenecks remain in the validation phase. Quantitative PCR, the most widely used orthogonal approach, lacks a universally accepted endogenous control for circulating miRNAs. Small RNAs such as U6 or 5S rRNA are unstable in biofluids and therefore unsuitable41,42. Several endogenous miRNAs (e.g., miR-15b, miR-16, miR-24) have been proposed as alternatives43, yet consensus is lacking. Additional complexity is introduced by isomiRs, which may confound both sequencing-based quantification and qPCR validation44. Efforts to optimize qPCR platforms and develop biofluid-specific quality controls are ongoing but not yet standardized45.

Taken together, these challenges explain why circulating miRNAs, despite their biological plausibility and technical appeal, remain difficult to integrate into routine diagnostics. Our findings underscore that, while aberrant levels of certain circulating miRNAs are associated with BM, their diagnostic performance is currently limited. Progress will require larger, well-matched cohorts, harmonized laboratory and computational pipelines, and integration of liquid biopsy miRNA analysis with complementary approaches such as imaging or proteomics to improve diagnostic precision.

Conclusion

In this study, we performed a comprehensive small RNA sequencing analysis of tissue, CSF, and plasma samples from patients with brain metastases originating from five primary tumor types (non-small cell lung carcinoma, breast carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, melanoma, and renal clear cell carcinoma). Nearly every patient contributed all three types of material, providing a unique dataset for direct cross-biopsy comparison.

Our findings demonstrate that tissue-derived miRNA profiles show strong discriminatory power to classify BM origin, with high sensitivity and specificity across most groups, although heterogeneity was evident in non-small cell lung carcinoma. In contrast, CSF and plasma miRNA profiles revealed only limited discriminatory capacity, with plasma in particular showing high contamination by non-specific miRNAs and strong influence from the molecular background of the primary tumor. While CSF appeared less affected by systemic signals and shared some deregulated miRNAs with tissue, its diagnostic potential remained modest in the current cohort.

Functional enrichment analysis of tissue deregulated miRNAs highlighted convergence on key cancer-related pathways, including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, apoptosis, and receptor-mediated signaling, suggesting that miRNA dysregulation in BMs reflects broad disruption of fundamental tumor suppressor and proliferative networks.

Overall, tissue remains the most reliable source for miRNA-based BM classification, while liquid biopsies—particularly CSF—may provide complementary information but are unlikely to substitute for tissue analysis in their current form. Larger and more diverse cohorts, standardized workflows, and integration with other diagnostic modalities will be required to clarify whether circulating miRNAs can be developed into robust clinical biomarkers for brain metastasis management. From a clinical perspective, future strategies will likely depend on combining molecular profiling of tissue and liquid biopsies with imaging and clinical parameters to achieve earlier, more accurate diagnosis and to optimize personalized treatment planning.

Data availability

The sequencing data have been deposited in the GEO repository under accession number GSE307043 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE307043). The following secure token has been created to allow review of record GSE307043 while it remains in private status: irqnmkakzxmjbsr.

Abbreviations

- BM:

-

Brain metastasis

- BMB:

-

Breast carcinoma brain metastasis

- BMC:

-

Colorectal carcinoma brain metastasis

- BML:

-

Non-small cell lung carcinoma brain metastasis

- BMM:

-

Melanoma brain metastasis

- BMR:

-

Renal clear cell carcinoma brain metastasis

- cDNA:

-

Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CRC:

-

Colorectal carcinoma

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- DE:

-

Differentially expressed/Differential expression

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EGFR:

-

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- FC:

-

Fold change

- GBM:

-

Glioblastoma

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LRT:

-

Likelihood ratio test

- miRNA:

-

MicroRNA

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- ORA:

-

Over-representation analysis

- padj:

-

Adjusted p-value (Benjamini-Hochberg)

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein 1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death-ligand 1

- QC:

-

Quality control

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- UMI:

-

Unique molecular identifier

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Ostrom, Q. T., Wright, C. H. & Barnholtz-Sloan, J. S. Brain metastases: Epidemiology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 149, 27–42 (2018).

Kotecha, R., Gondi, V., Ahluwalia, M. S., Brastianos, P. K. & Mehta, M. P. Recent advances in managing brain metastasis. F1000Res 7 (2018).

Schouten, L. J., Rutten, J., Huveneers, H. A. M. & Twijnstra, A. Incidence of brain metastases in a cohort of patients with carcinoma of the breast, colon, kidney, and lung and melanoma. Cancer 94(10), 2698–2705. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.10541 (2002).

Polyzoidis, K. S., Miliaras, G. & Pavlidis, N. Brain metastasis of unknown primary: A diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 31(4), 247–255 (2005).

Carnevale, J. A. et al. Risk of tract recurrence with stereotactic biopsy of brain metastases: An 18-year cancer center experience. J. Neurosurg. 136(4), 1045 (2022).

Rehman, A. U. et al. Liquid biopsies to occult brain metastasis. Mol. Cancer 21(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-022-01577-x (2022).

Teplyuk, N. M. et al. MicroRNAs in cerebrospinal fluid identify glioblastoma and metastatic brain cancers and reflect disease activity. Neuro Oncol. 14(6), 689–700 (2012).

Kopkova, A. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid MicroRNA signatures as diagnostic biomarkers in brain tumors. Cancers 11(10), 1546 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Plasma specific miRNAs as predictive biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of glioma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 31(1), 97 (2012).

Roskova, I. et al. Small RNA sequencing identifies a six-MicroRNA signature enabling classification of brain metastases according to their origin. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 20(1), 18–29 (2023).

Kirschner, M. B. et al. The impact of hemolysis on cell-free microRNA biomarkers. Front. Genet. 4, 94 (2013).

Juzenas, S. et al. Depletion of erythropoietic miR-486–5p and miR-451a improves detectability of rare microRNAs in peripheral blood-derived small RNA sequencing libraries. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2(1), lqaa008 (2020).

NextSeq 500 and 550 System Denature and Dilute Libraries Guide [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 29]. Available from: https://emea.support.illumina.com/downloads/nextseq-500-denaturing-diluting-libraries-15048776.html

Babraham Bioinformatics - FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 29]. Available from: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17(1), 10–12 (2011).

FASTX-Toolkit [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jan 29]. Available from: http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/

Griffiths-Jones, S., Grocock, R. J., van Dongen, S., Bateman, A. & Enright, A. J. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D140–D144 (2006).

Pantano, L., Estivill, X. & Martí, E. SeqBuster, a bioinformatic tool for the processing and analysis of small RNAs datasets, reveals ubiquitous miRNA modifications in human embryonic cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 38(5), e34 (2010).

Ewels, P., Magnusson, M., Lundin, S. & Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 32(19), 3047 (2016).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15(12), 550 (2014).

Bioconductor - clusterProfiler [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: Biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53(1), 672–677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D457–D462 (2016).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Lam, T. C., Sahgal, A., Chang, E. L. & Lo, S. S. Stereotactic radiosurgery for multiple brain metastases. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 14(10), 1153–1172 (2014).

Tong, E., McCullagh, K. L. & Iv, M. Advanced imaging of brain metastases: From augmenting visualization and improving diagnosis to evaluating treatment response. Front. Neurol. 11, 270 (2020).

de Sousa, V. M. L. & Carvalho, L. Heterogeneity in lung cancer. Pathobiology 85(1–2), 96–107 (2018).

Dufourd, T. et al. Plasma or serum? A qualitative study on rodents and humans using high-throughput microRNA sequencing for circulating biomarkers. Biol. Methods Protoc. 4(1), bpz006 (2019).

Smith, M. D. et al. Haemolysis detection in MicroRNA-Seq from clinical plasma samples. Genes 13(7), 1288 (2022).

Sell, M. C., Ramlogan-Steel, C. A., Steel, J. C. & Dhungel, B. P. MicroRNAs in cancer metastasis: Biological and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Mol. 25, e14 (2023).

Hassanein, S. S., Ibrahim, S. A. & Abdel-Mawgood, A. L. Cell behavior of non-small cell lung cancer is at EGFR and MicroRNAs hands. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(22), 12496 (2021).

Yadav, R. et al. The miRNA and PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis: An arsenal of immunotherapeutic targets against lung cancer. Cell Death Discov. 10(1), 1–19 (2014).

Bleazard, T., Lamb, J. A. & Griffiths-Jones, S. Bias in microRNA functional enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics 31(10), 1592–1598. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv023 (2015).

Fridrich, A., Hazan, Y. & Moran, Y. Too many false targets for microRNAs: Challenges and pitfalls in prediction of miRNA targets and their gene ontology in model and non-model organisms. BioEssays 41(4), e1800169 (2019).

Wong, R. K. Y., MacMahon, M., Woodside, J. V. & Simpson, D. A. A comparison of RNA extraction and sequencing protocols for detection of small RNAs in plasma. BMC 20(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5826-7 (2019).

Duttagupta, R., Jiang, R., Gollub, J., Getts, R. C. & Jones, K. W. Impact of cellular miRNAs on circulating miRNA biomarker signatures. PLoS ONE 6(6), 20769 (2011).

MaClellan, S. A., Macaulay, C., Lam, S. & Garnis, C. Pre-profiling factors influencing serum microRNA levels. BMC Clin. Pathol. 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6890-14-27 (2014).

Liang, H. et al. Effective detection and quantification of dietetically absorbed plant microRNAs in human plasma. J. Nutr. Biochem. 26(5), 505–512 (2015).

Samandari, N. et al. Influence of disease duration on circulating levels of miRNAs in children and adolescents with new onset type 1 diabetes. Noncoding RNA 4(4), 35 (2018).

Balzano, F. et al. miRNA stability in frozen plasma samples. Molecules 20(10), 19030 (2015).

Benz, F. et al. U6 is unsuitable for normalization of serum miRNA levels in patients with sepsis or liver fibrosis. Exp Mol Med 45(9), e42 (2013).

Xiang, M. et al. U6 is not a suitable endogenous control for the quantification of circulating microRNAs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 454(1), 210–214 (2014).

Mitchell, P. S. et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105(30), 10513–10518 (2008).

Avendaño-Vázquez, S. E. & Flores-Jasso, C. F. Stumbling on elusive cargo: How isomiRs challenge microRNA detection and quantification, the case of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 9(1), 1784617 (2020).

Blondal, T. et al. 2013 Assessing sample and miRNA profile quality in serum and plasma or other biofluids. Methods 59(1), S1–S6 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Core Facility Genomics, supported by the NCMG research infrastructure (project LM2018132 funded by MEYS CR), and Core Facility Bioinformatics of CEITEC Masaryk University for their support with obtaining of the scientific data presented in this paper.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (grant project nr. NV18-03-00398), by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic (MEYS CR, program EXCELES; grant projects nr. LX22NPO5102 and LX22NPO5107; financed by the European Union – Next Generation EU), and conceptual development of research organizations (Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute, 00209805; University Hospital Brno, 65269705). The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S., M.S., and R.Ja. acquired funding; J.S. and V.V. conceptualized the study; M.S., R.Ja., and T.K. selected suitable patients for the study a provided clinical data; M.Her., M.Hen., and L.K. histopathologically verified the tumors; V.V., P.F., and H.V. arranged the collection of biological material and the signing of informed consents by the patients; V.V. administered all the clinicopathological data, and supervised the clinical part of the study; O.S. supervised laboratory part of the study; M.R., M.V., and T.D. performed laboratory analyses; D.A.T. and R.Ju. performed bioinformatics processing of measured data, statistical analyses, and data visualization; J.S. ensured communication between clinical and academic researchers, and transport of biological material; M.R. and D.A.T. wrote the original draft; M.R., D.A.T., J.S., V.V., R.Ja., M.S., and O.S. revised the original draft. M.R., J.S., and M.S. participated in reworking the manuscript during the revision process. All Authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study and the informed consent form were approved by the research ethics committee of University Hospital Brno under the code EKFNB-17-06-28-01. A signed informed consent form was obtained from each patient prior to the beginning of all procedures and the collection of patient tissue, peripheral blood, and CSF samples. The study methodologies obeyed the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruckova, M., Al Tukmachi, D., Vecera, M. et al. Circulating MicroRNAs do not provide a diagnostic benefit over tissue biopsy in patients with brain metastases. Sci Rep 16, 1780 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31344-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31344-z