Abstract

Dyslipidemia may affect pulmonary function through systemic inflammation and metabolic pathways; however, longitudinal evidence remains limited. This study examined the associations of baseline low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels with subsequent rates of lung function decline and the incidence of airflow obstruction in a community-based observational cohort, Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES). We analyzed 7381 participants without baseline airflow obstruction. LDL cholesterol was categorized as ≤ 130 mg/dL (LDLlow), 130–160 mg/dL (LDLmedium), and > 160 mg/dL (LDLhigh), while HDL cholesterol was classified as ≤ 50 mg/dL (HDLlow) and > 50 mg/dL (HDLhigh). Annual changes in FEV₁ and FVC were estimated using linear mixed-effects models, and Cox proportional hazards models were applied to assess the risk of incident airflow obstruction. Compared with the LDLlow group, participants in the LDLhigh group had a slower annual decline in FEV₁ (− 37.21 mL/year, 95% CI: −39.00 to − 35.43) versus (− 40.39 mL/year, 95% CI: −40.94 to − 39.84) and FVC (− 30.06 mL/year, 95% CI: −32.18 to − 27.94) versus (− 35.78 mL/year, 95% CI: −36.43 to − 35.13), respectively (both p < 0.001). Higher LDL levels were significantly associated with a lower risk of incident airflow obstruction (adjusted HR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.54–0.92). In contrast, higher HDL levels were associated with a faster FEV₁ decline (− 41.34 mL/year, 95% CI: −42.44 to − 40.24) compared with HDLlow (− 37.84 mL/year, 95% CI −38.46 to − 37.22, p < 0.001), but not with FVC decline or incident airflow obstruction. Higher baseline LDL cholesterol levels were associated with a slower decline in lung function and a lower risk of developing airflow obstruction, whereas higher HDL cholesterol levels were associated with an accelerated decline in FEV₁. These findings highlight complex, potentially bidirectional relationships between lipid metabolism and respiratory outcomes, warranting further mechanistic research. Importantly, these associations should not be interpreted as implying that high LDL is beneficial for general health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite decades of research and public health interventions, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains a significant challenge to global health systems. Approximately 10.3% of people aged 30–79 years—translating to 391.9 million individuals worldwide— were affected by COPD based on the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) case definition, with over 80% of cases concentrated in resource-limited regions1,2. The economic burden of COPD is also very high3. COPD is a systemic disease characterized by persistent airflow obstruction and a gradual decline in lung function4. Chronic inflammation not only affects the lungs, but also affects extrapulmonary sites, leading to cardiovascular disease, muscle wasting, and metabolic abnormalities5,6.

Dyslipidemia – especially high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol – is a well-established risk factor for cardiovascular disease due to its role in atherosclerosis and systemic inflammation7,8. There is growing interest in how such metabolic factors might be related to chronic lung disease. Shared mechanisms such as inflammation and oxidative stress could contribute to both atherosclerotic progression and lung function decline9. Indeed, impaired lung function and cardiovascular risk factors often coexist. Conditions such as type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome have been associated with reduced pulmonary function in epidemiologic studies10,11,12. In addition, findings from the Copenhagen General Population Study have revealed that individuals with lower plasma LDL cholesterol have higher odds of having COPD at baseline and are at increased risks of severe exacerbations and COPD-specific mortality during follow-up13. However, the longitudinal impact of baseline cholesterol levels on the trajectory of lung function and the development of COPD remains poorly understood.

This study aimed to evaluate associations of baseline LDL and HDL cholesterol levels with subsequent lung function decline and incident airflow obstruction using data from a large community-based longitudinal observational cohort with repeated spirometry measurements, Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES). We hypothesized that unfavorable lipid profiles would be associated with more rapid lung function decline and higher risk of obstruction.

Methods

Study design and population

Data from a population-based longitudinal cohort comprising the rural and urban populations were analyzed. This cohort enrolled adults aged 40 to 69 years from the general population to investigate the incidence and risk factors of chronic diseases. Baseline data were collected between 2001 and 2002. Participants were followed up every two years until 2014. During each follow-up visit, data of participants’ lifestyle habits, clinical history, subjective symptoms, and incident diseases were collected. Detailed methodology has been described in prior publications14.

For this study, individuals who had undergone at least three spirometry assessments and had baseline measurements of both LDL and HDL cholesterol were included. Participants with baseline airflow obstruction (defined as FEV₁/FVC < 0.7) were excluded to focus on lung function decline in individuals without pre-existing obstructive lung disease.

Clinical variables

Baseline data collection included demographic, medical, and lifestyle factors. Participants provided information on age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). Socioeconomic variables, including residential area (urban or rural), marital status, education level, and income, were also recorded. Smoking history was categorized as never, former, or current, with cumulative tobacco exposure quantified in pack-years. Occupational exposure to dust and chemicals was additionally documented.

Respiratory symptoms were assessed by asking participants about the presence of dyspnea. Its severity was evaluated using the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale. Chronic bronchitis was defined as having cough and sputum production for at least three months in two consecutive years. Participants were also assessed for comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (coronary artery disease, prior myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure), dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease, arthritis, and thyroid disorders.

Pulmonary function assessment

Lung function was assessed using spirometry (Vmax-2130, SensorMedics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁), forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV₁/FVC ratio, and forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of FVC (FEF₂₅–₇₅) were measured. All tests were performed pre-bronchodilation and conducted in accordance with American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) 2005 guidelines15, with regular calibration and quality control. Results were recorded both in liters and as percentages of predicted values.

LDL and HDL cholesterol classification

Serum lipid levels were measured at baseline using an ADVIA 1650 analyzer from 2002 to 2010 and an ADVIA analyzer 1800 from 2011 onward. All analyses were conducted at a central laboratory with routine internal and external quality control procedures to ensure measurement accuracy.

For this study, LDL and HDL cholesterol levels were categorized according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP ATP III) guideline16. LDL cholesterol was divided into three groups: ≤ 130 mg/dL (LDLlow, optimal to borderline high), 130–160 mg/dL (LDLmedium, borderline high), and > 160 mg/dL (LDLhigh, high). HDL cholesterol was classified into two groups. HDL cholesterol ≤ 50 mg/dL was considered low (HDLlow) and HDL cholesterol > 50 mg/dL was considered optimal (HDLhigh).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Participants with missing baseline LDL or HDL cholesterol values or incomplete spirometry data were excluded from the analysis. No imputation was performed, and a complete-case analysis approach was applied. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Differences in baseline characteristics were analyzed according to LDL and HDL cholesterol groups. For continuous variables, comparisons across LDL groups were made using analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc test to identify pairwise group differences, while differences between HDL groups were assessed using independent t-test. Normality and homogeneity of variance for continuous variables were evaluated using skewness statistics, Levene’s test, and graphical residual diagnostics (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). Chi-square (χ²) test was used to evaluate differences in categorical variables. To evaluate associations of cholesterol categories with annualized lung function decline, linear mixed models were used to estimate annual changes of FEV₁, FVC, FEV₁/FVC, and FEF₂₅–₇₅ over the follow-up period. Models were adjusted for age, sex, height, weight, and smoking status.to account for potential confounding factors.

Additionally, Cox proportional hazards analysis was conducted to estimate the time to first occurrence of airflow obstruction (AFO) during the follow-up period. Log-rank test was used to assess statistical differences between survival curves. Cox proportional hazards models were applied to calculate adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) for AFO according to LDL and HDL cholesterol categories. Covariates including age, sex, height, weight, and smoking status were adjusted for to control for potential confounding. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with p-values < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

To further explore potential effect modification, subgroup analyses were conducted by sex, age (< 60 vs. ≥ 60 years), smoking status and probable statin-use (Supplementary Tables 2, 3). To address potential confounding by lipid-lowering therapy given the limitations of self-reported data, we performed a sensitivity analysis defining ‘probable statin users’ based on longitudinal lipid profiles (Supplementary Table 1). Participants were classified as probable statin users if they exhibited a reduction in LDL cholesterol of ≥ 14.6% at the 2-year follow-up compared to baseline, provided their baseline LDL was ≥ 55 mg/dL17,18. Participants not meeting these criteria were classified as probable non-users.

Results

Differences of baseline characteristics according to different cholesterol groups

A total of 7,381 participants were included in the analysis. Among the 7,381 participants, 5,136 were classified as LDLlow, 1,642 as LDLmedium, and 603 as LDLhigh (Table 1). Mean age differed significantly across LDL groups, with the highest mean age observed in the LDLmedium group and the lowest in the LDLlow group. There were no significant differences in sex distribution between groups. BMI increased with higher LDL levels, ranging from 24.4 ± 3.1 kg/m² in the LDLlow group to 25.3 ± 2.9 kg/m² in the LDLhigh group. The proportion of non-smokers decreased with increasing LDL levels, although total pack-years of smoking did not differ significantly across groups. Respiratory symptoms, including the presence of dyspnea, mMRC dyspnea scale scores, and chronic bronchitis, showed no significant differences across LDL groups. Participants with elevated LDL levels showed higher prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and cerebrovascular disease. However, prevalence of diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease did not differ significantly between groups. In terms of lung function, higher LDL levels were associated with lower FEV₁ and FVC but a higher FEV₁/FVC ratio. No significant trend was observed for FEF₂₅–₇₅.

For HDL cholesterol, 3,996 participants and 3,385 were classified as HDLlow and HDLhigh, respectively (Table 2). Age was slightly higher in the HDLlow group than in the HDLhigh group. The proportion of male participants was significantly higher in the HDLlow group than in the HDLhigh group (66.3% vs. 33.6%, p < 0.01). BMI was also higher in the HDLlow group than in the HDLhigh group (25.2 ± 3.0 vs. 24.0 ± 3.0 kg/m², p < 0.01). Regarding smoking history, the proportion of non-smokers was higher in the HDLlow group (70.3%) than in the HDLhigh group (45.3%). Dyspnea was more prevalent in the HDLlow group as reflected by a higher proportion of participants with elevated mMRC scores (p < 0.01). However, comorbidities were not significantly different between groups except that arthritis was more prevalent in the HDLlow group. Lung function parameters including FVC, FEV₁, and FEF₂₅–₇₅ were significantly higher in the HDLhigh group than in the HDLlow group.

Impact of LDL and HDL cholesterol on pulmonary function changes

Table 3 presents differences in annual lung function decline according to cholesterol groups. For LDL cholesterol, the annual decline in FEV₁ was significantly greater in the LDLlow group (–40.39 mL/year, 95% CI: −40.94 to − 39.84) than in LDLmedium (− 37.32 mL/year, 95% CI: −38.94 to − 35.70) and LDLhigh groups (− 37.21 mL/year, 95% CI: −39.00 to − 35.43; p < 0.01). A similar pattern was observed for FVC, with the LDLlow group showing more rapid decline (–35.78 mL/year, 95% CI: −36.43 to − 35.13) than the LDLhigh group (− 30.06 mL/year, 95% CI: −32.18 to − 27.94; p < 0.01).

Regarding HDL cholesterol, participants in the HDLhigh group exhibited a significantly faster annual decline in FEV₁ (− 41.34 mL/year, 95% CI: −42.44 to − 40.24) compared with the HDLlow group (− 37.84 mL/year, 95% CI: −38.46 to − 37.22; p < 0.01). However, annual decline of FVC showed no significant difference between the HDLhigh group (− 33.12 mL/year, 95% CI: −34.21 to − 32.03) and the HDLlow group (− 34.01 mL/year, 95% CI: −35.02 to − 33.00; p = 0.60).

In subgroup analyses stratified by sex, age (< 60 vs. ≥ 60 years), smoking status (never, former, current) and probable statin use, slower annual decline in FEV₁ in the LDLhigh group was observed in most subgroups, with statistically significant differences in men, participants aged ≥ 60 years, and former smokers. In contrast, the faster decline in FEV₁ in the HDLhigh group was observed across subgroups, while no significant subgroup differences were observed for the risk of incident airflow obstruction (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Association of LDL and HDL cholesterol levels with incident airway obstruction

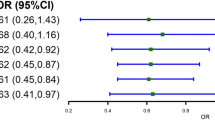

Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Fig. 1) demonstrated a significantly lower cumulative incidence of airflow obstruction in the LDLhigh group than in the LDLlow group (log-rank p = 0.02). Consistently, participants in the LDLhigh group had a significantly reduced risk of developing airflow obstruction (aHR: 0.71, 95% CI: 0.54–0.92, p = 0.01) in Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for confounders (Table 4). Although Kaplan–Meier curves for HDL cholesterol groups showed a statistically significant difference in time to airflow obstruction (log-rank p < 0.01), HDL levels showed no significant association with the risk of airflow obstruction (HR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.89–1.18, p = 0.76) after controlling for confounding factors.

Kaplan–Meier curves for time to first airway obstruction stratified by cholesterol levels. (A) Time to first airway obstruction stratified by LDL cholesterol categories. Differences were statistically significant between LDLlow and LDLhigh groups (p = 0.027). (B) Time to first airway obstruction stratified by HDL cholesterol levels. No significant difference was observed between groups (p = 0.626).

Discussion

This longitudinal cohort study based on a general adult population found that baseline cholesterol levels had significant and somewhat unexpected associations with pulmonary outcomes over time. Higher LDL cholesterol was associated with slower declines of FEV₁ and FVC as well as a lower incidence of developing airflow obstruction. In contrast, higher HDL cholesterol was linked to a more rapid decline in FEV₁, although it did not significantly affect the risk of incident airflow obstruction. These findings challenge the conventional assumption that LDL is inherently harmful while HDL is protective in terms of overall health. Instead, our results point to a paradoxical relationship between lipid profiles and pulmonary function decline.

Our findings regarding the protective role of elevated LDL cholesterol in lung function are consistent with those of several previous studies. Freyberg et al. have conducted a cross-sectional and prospective cohort analysis using data from over 100,000 participants in the Copenhagen General Population Study to examine the association between plasma LDL cholesterol levels and COPD-related outcomes13. They found that participants in the lowest LDL cholesterol quartile had 1.27-fold higher odds of having COPD at baseline compared to those in the highest quartile. In addition, lower LDL levels were associated with increased risks of future severe COPD exacerbations (adjusted HR 1.43, 95% CI 1.21–1.70 for the 1st versus 4th quartile of LDL cholesterol) and COPD-specific mortality (log-rank p < 0.01). Similarly, Kahnert et al. have demonstrated in the COSYCONET cohort study that hyperlipidemia is associated with reduced hyperinflation, lower airway obstruction, and higher FEV1 in COPD patients19. Furthermore, Holmes et al. have provided genetic evidence that PCSK9 gene variants associated with lower cholesterol levels are also linked to an increased risk of COPD in both Chinese and UK populations20. In addition, in a study of adults with cystic fibrosis, individuals with overweight, who also had higher LDL cholesterol levels, had better lung function and experienced fewer pulmonary exacerbations than their normal-weight individuals21. These studies support our finding that elevated LDL cholesterol potentially offers protection against pulmonary function impairment.

The observed association between higher LDL levels and slower lung function decline might be explained by the role of cholesterol in maintaining cell membrane integrity and function. Cholesterol is a fundamental component of cell membranes influencing their fluidity and activities of membrane-associated proteins22. In pulmonary tissues where cellular membranes are subject to mechanical stress during respiration, adequate cholesterol levels might be crucial for maintaining structural integrity and function23. Moreover, cholesterol metabolites can modulate inflammatory responses in the lungs, potentially affecting airway remodeling and alveolar function24. Lipoproteins are involved in lipid-mediated signaling pathways that can impact pulmonary endothelial and epithelial cell integrity, further influencing lung function over time25. Recent studies have demonstrated that lipid metabolism plays a crucial role in pulmonary cell function, with cholesterol levels affecting smooth muscle cell signaling, which could influence airway mechanics26. Additionally, cholesterol is a critical component of pulmonary surfactant that plays an essential role in maintaining alveolar stability and preventing collapse during respiration27.

The relationship between lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses in pulmonary tissue might also contribute to our findings. Tam et al. have recently reported that nitric oxide produced in human lung epithelial cells through inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) can restrict both inflammatory activation and cholesterol/fatty acid biosynthesis28. This regulatory pathway might link lipid metabolism to inflammatory processes in the lungs, potentially explaining some of the observed associations between cholesterol levels and lung function decline.

Roles of obesity and nutrition might also need to be considered. Higher LDL often correlates with diets rich in saturated fats and higher body mass index29. Epidemiologic studies on COPD have noted that patients who are underweight or have low BMI suffer worse outcomes, whereas those who are overweight sometimes have better survival, which is the so-called obesity paradox30,31. In our cohort, although we adjusted for height and weight, high LDL levels might still reflect aspects of nutritional status not captured by BMI alone (such as muscle mass or micronutrient intake). It is possible that individuals with very low LDL might have included some who are malnourished or have subclinical illness. Such individuals could experience faster lung decline. Conversely, individuals with moderately elevated LDL might have had better nutritional reserves. Additionally, weight cycling or unintentional weight loss (which we did not measure) could influence both cholesterol levels and lung function trajectory.

Interestingly, higher HDL cholesterol was associated with a faster decline in FEV₁. Recent studies have shown that, paradoxically, higher HDL cholesterol levels are associated with a faster decline in lung function as measured by FEV₁ in certain populations. For instance, Park et al. observed this relationship in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses32, and similar findings were corroborated in multi-year cohort studies among COPD patients33. Although HDL is typically protective in cardiovascular contexts, recent evidence suggests that chronic inflammation or oxidative stress can transform HDL into a dysfunctional form, causing it to lose its antioxidant capacity and contribute to pulmonary inflammation34,35. Research on dysfunctional HDL—marked by compositional changes driven by myeloperoxidase and other modifying enzymes—demonstrates a shift toward pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidant roles, which may increase intrapulmonary inflammation and tissue damage34,36. These findings indicate that dysfunctional HDL may help explain the observed link between higher HDL cholesterol and accelerated lung-function decline.

In contrast to our findings, several studies have reported contradictory results regarding the relationship between cholesterol level and pulmonary function. Lee et al. analyzed data from three large national health surveys (KNHANES, NHANES III, and NHANES 2007–2012) and found that higher HDL-C levels were consistently associated with better FVC and FEV₁ across all cohorts37. Cirillo et al. also reported that increased HDL cholesterol or apolipoprotein A-I was associated with higher FEV₁, whereas elevated LDL cholesterol or apolipoprotein B levels were linked to lower FEV138. However, other investigations have shown opposite or context-dependent associations. Xuan et al. demonstrated that patients with COPD had lower total cholesterol and HDL-C but higher LDL-C and triglyceride levels compared with controls39. Yang et al. reported that hyperlipidemia was associated with an increased risk of developing COPD in a nationwide population-based cohort40. In addition, Kotlyarov highlighted the pro-inflammatory role of HDL in COPD, suggesting that HDL may become dysfunctional under chronic inflammatory conditions41. These discrepancies might be associated with differences in study design (e.g., cross-sectional versus longitudinal cohorts), analytical adjustments (including statin use and inflammatory markers), and the underlying health status of study populations such as age distribution and prevalence of cardiometabolic comorbidities. Further studies are needed to clarify these associations and to better understand biological mechanisms linking lipid metabolism to pulmonary function.

Although the LDLhigh group showed a statistically slower annual decline in FEV₁, the absolute difference (~ 4 mL/year) is well below the minimal clinically important difference42. Therefore, these results should be regarded as mechanistic observations rather than clinically meaningful effects. Elevated LDL cholesterol remains a well-established cardiovascular risk factor, and our findings do not imply that higher LDL levels confer health benefits43.

Our study has several limitations. First, our cohort consisted of middle-aged adults. Thus, generalizability of our study findings to other ethnic groups or older populations is uncertain as genetic, dietary, and lifestyle factors that influence lipid profiles and lung health might differ across populations. Second, we did not assess changes in lipid profiles over time. Such assessment might have provided additional insights into the dynamic relationship between lipid metabolism and lung function. Third, we did not account for the initiation of cholesterol-lowering therapies during follow-up. If many participants with high LDL had started statin treatment, one might expect attenuation of the observed group differences, given the known pleiotropic and anti-inflammatory effects of statins which could potentially mitigate lung function decline44,45. However, information on statin use was obtained from a self-reported medication survey, which indicated extremely low usage across LDL groups (0.5% in LDLlow, 0.8% in LDLmedium, and 1.4% in LDLhigh). These implausibly low values likely reflect under-reporting rather than true absence of therapy. Because the data were based on self-report rather than verified prescription records, their reliability was limited. Although self-reported medication history was limited, we performed a sensitivity analysis using longitudinal LDL reduction as a proxy for statin initiation (Supplementary Tables 1–3). However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously, as statin exposure was estimated based on calculated LDL changes rather than verified medication records.

The protective association between higher LDL levels and lung function remained significant in the probable non-user group, suggesting that our main findings are likely robust to the potential confounding effects of lipid-lowering medication. The potential influence of unmeasured or under-reported statin use was therefore acknowledged as an important limitation. Fourth, although the use of pre-bronchodilator spirometry values was consistent with previous research, it might not fully capture airflow obstruction in certain populations. However, many studies have relied on pre-bronchodilator spirometry value as a surrogate for post-bronchodilator measurements when assessing COPD diagnosis, clinical characteristics, and long-term outcomes46,47,48. Finally, while associations observed are robust, they might not imply a causal relationship. It is possible that elevated LDL cholesterol reflects other physiological or metabolic conditions that contribute to preserved lung function.

In conclusion, this community-based cohort study found that higher baseline LDL cholesterol was associated with slower declines of FEV₁ and FVC as well as a lower risk of developing airflow obstruction over 14 years. Higher HDL cholesterol was associated with faster lung function decline, while no statistically significant association was observed with incident airflow obstruction. These findings might challenge the conventional view that LDL is harmful while HDL is beneficial in the context of lung function. Further research is warranted to clarify the underlying mechanisms involved in the relationship between lipid metabolism and pulmonary outcome.

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adeloye, D. et al. Global, regional, and National prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 10, 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(21)00511-7 (2022).

Lowe, K. E. et al. COPDGene(®) 2019: redefining the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Obstr. Pulm Dis. 6, 384–399. https://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.6.5.2019.0149 (2019).

Pham, H. Q. et al. Economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Tuberc Respir Dis. (Seoul). 87, 234–251. https://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2023.0100 (2024).

López-Campos, J. L., Tan, W. & Soriano, J. B. Global burden of COPD. Respirology 21, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.12660 (2016).

Huertas, A. & Palange, P. COPD: a multifactorial systemic disease. Ther. Adv. Respir Dis. 5, 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753465811400490 (2011).

Fabbri, L. M. et al. COPD and multimorbidity: recognising and addressing a syndemic occurrence. Lancet Respir Med. 11, 1020–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(23)00261-8 (2023).

Gaggini, M., Gorini, F. & Vassalle, C. Lipids in atherosclerosis: pathophysiology and the role of calculated lipid indices in assessing cardiovascular risk in patients with hyperlipidemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010075 (2022).

Marchio, P. et al. Targeting early atherosclerosis: A focus on oxidative stress and inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019 (8563845). https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/8563845 (2019).

Hughes, M. J., McGettrick, H. M. & Sapey, E. Shared mechanisms of Multimorbidity in COPD, atherosclerosis and type-2 diabetes: the neutrophil as a potential inflammatory target. Eur. Respir Rev. 29 https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0102-2019 (2020).

Leone, N. et al. Lung function impairment and metabolic syndrome: the critical role of abdominal obesity. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 179, 509–516. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200807-1195OC (2009).

Chen, W. L. et al. Relationship between lung function and metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 9, e108989. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108989 (2014).

Yeh, F. et al. Obesity in adults is associated with reduced lung function in metabolic syndrome and diabetes: the strong heart study. Diabetes Care. 34, 2306–2313. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-0682 (2011).

Freyberg, J., Landt, E. M., Afzal, S., Nordestgaard, B. G. & Dahl, M. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of COPD: Copenhagen general population study. ERJ Open. Res. 9 https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00496-2022 (2023).

Kim, Y. & Han, B. G. Cohort profile: the Korean genome and epidemiology study (KoGES) consortium. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, e20. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv316 (2017).

ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the. Online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide, 2005. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 171, 912–930. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200406-710ST (2005).

Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert panel on Detection, Evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation 106, 3143–3421 (2002).

Karlson, B. W. et al. Variability of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol response with different doses of atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, and simvastatin: results from VOYAGER. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2, 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw006 (2016).

Rhee, E. J. et al. Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia in Korea. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 8, 78–131 https://doi.org/10.12997/jla.2019.8.2.78 (2019).

Kahnert, K. et al. Relationship of hyperlipidemia to comorbidities and lung function in COPD: results of the COSYCONET cohort. PLoS One. 12, e0177501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177501 (2017).

Holmes, M. V. et al. PCSK9 genetic variants and risk of vascular and non-vascular diseases in Chinese and UK populations. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 31, 1015–1025. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwae009 (2024).

Harindhanavudhi, T., Wang, Q., Dunitz, J., Moran, A. & Moheet, A. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity in adults with cystic fibrosis: A single-center analysis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 19, 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2019.10.004 (2020).

Farooqui, A. A., Farooqui, T. & Phospholipids Sphingolipids, and Cholesterol-Derived lipid mediators and their role in neurological disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms251910672 (2024).

Beverley, K. M. & Levitan, I. Cholesterol regulation of mechanosensitive ion channels. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 12, 1352259. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2024.1352259 (2024).

Bottemanne, P. et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterol metabolism is altered by lung inflammation, and its local administration modulates lung inflammation in mice. Faseb j. 35, e21514. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202002555R (2021).

Kočar, E., Režen, T. & Rozman, D. Cholesterol, lipoproteins, and COVID-19: basic concepts and clinical applications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids. 1866, 158849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2020.158849 (2021).

Norton, C. E. et al. Altered lipid domains facilitate enhanced pulmonary vasoconstriction after chronic hypoxia. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 62, 709–718. https://doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2018-0318OC (2020).

Díaz, M. Multifactor Analyses of Frontal Cortex Lipids in the APP/PS1 Model of Familial Alzheimer’s Disease Reveal Anomalies in Responses to Dietary n-3 PUFA and Estrogenic Treatments. Genes (Basel). 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15060810 (2024).

Tam, F. F., Dumlao, J. M., Lee, A. H. & Choy, J. C. Endogenous production of nitric oxide by iNOS in human cells restricts inflammatory activation and cholesterol/fatty acid biosynthesis. Free Radic Biol. Med. 231, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2025.02.022 (2025).

Ozen, E. et al. Association between dietary saturated fat with cardiovascular disease risk markers and body composition in healthy adults: findings from the cross-sectional BODYCON study. Nutr. Metab. (Lond). 19, 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-022-00650-y (2022).

Cao, C. et al. Body mass index and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 7, e43892. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043892 (2012).

Putcha, N. et al. Mortality and exacerbation risk by body mass index in patients with COPD in TIOSPIR and UPLIFT. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 19, 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-722OC (2022).

Park, J. H., Mun, S., Choi, D. P., Lee, J. Y. & Kim, H. C. Association between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and pulmonary function in healthy Korean adolescents: the JS high school study. BMC Pulm Med. 17, 190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-017-0548-6 (2017).

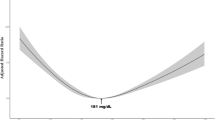

Wen, X. et al. The nonlinear relationship between High-Density lipoprotein and changes in pulmonary structure function and pulmonary function in COPD patients in China. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 19, 1801–1812. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S467976 (2024).

Bonizzi, A., Piuri, G., Corsi, F., Cazzola, R. & Mazzucchelli, S. HDL dysfunctionality: clinical relevance of quality rather than quantity. Biomedicines 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9070729 (2021).

Rosenson, R. S. et al. Dysfunctional HDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 13, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2015.124 (2016).

Carnuta, M. G. et al. Dysfunctional high-density lipoproteins have distinct composition, diminished anti-inflammatory potential and discriminate acute coronary syndrome from stable coronary artery disease patients. Sci. Rep. 7, 7295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07821-5 (2017).

Lee, C., Cha, Y., Bae, S. H. & Kim, Y. S. Association between serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and lung function in adults: three cross-sectional studies from US and Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. BMJ Open. Respir Res. 10 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2023-001792 (2023).

Cirillo, D. J., Agrawal, Y. & Cassano, P. A. Lipids and pulmonary function in the third National health and nutrition examination survey. Am. J. Epidemiol. 155, 842–848. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/155.9.842 (2002).

Xuan, L. et al. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and serum lipid levels: a meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-018-0904-4 (2018).

Yang, H. Y. et al. Increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients with hyperlipidemia: A nationwide Population-Based cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912331 (2022).

Kotlyarov, S. & High-Density Lipoproteins A role in inflammation in COPD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158128 (2022).

Vestbo, J. et al. Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in COPD. N Engl. J. Med. 365, 1184–1192. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105482 (2011).

Zhang, Y. et al. Association between cumulative Low-Density lipoprotein cholesterol exposure during young adulthood and middle age and risk of cardiovascular events. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 1406–1413. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3508 (2021).

Chen, X., Hu, F., Chai, F. & Chen, X. Effect of Statins on pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Thorac. Disease. 15, 3944–3952 (2023).

Mroz, R. M. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Atorvastatin treatment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A controlled pilot study. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 66, 111–128 (2015).

Choi, J. Y., Rhee, C. K., Kim, S. H. & Jo, Y. S. Muscle mass index decline as a predictor of lung function reduction in the general population. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13663 (2024).

Jo, Y. S., Rhee, C. K., Kim, S. H., Lee, H. & Choi, J. Y. Spirometric transition of at risk individuals and risks for progression to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general population. Arch. Bronconeumol. 60, 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2024.05.033 (2024).

Kim, S. et al. Longitudinal analysis of adiponectin to leptin and Apolipoprotein B to A1 ratios as markers of future airflow obstruction and lung function decline. Sci. Rep. 14, 29502. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80055-4 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with bioresources from National Biobank of Korea, The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, Republic of Korea (KBN-2023-005).

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the Catholic Medical Center Research Foundation made in the program year of 2024.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y.C. conceptualized the study and performed data analysis. J.Y. and J.Y.C wrote the original manuscript draft. C.K.R. and Y.S.J. provided critical comments and feedback on the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.Detailed Contributions: Study conception and design: J.Y.C.Data analysis: J.Y.C.Manuscript writing (original draft): J.Y., J.Y.CCritical review and feedback: C.K.R., Y.S.J.Final approval: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethic statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Incheon St. Mary’s hospital (IRB number: OC23ZISI0033). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Incheon St. Mary’s hospital due to the retrospective nature of this study. All analyses were performed using de-identified public data from the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES), and all methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, J., Rhee, C.K., Jo, Y.S. et al. Associations of LDL and HDL cholesterol with lung function decline and risk of airflow obstruction in a community-based cohort. Sci Rep 16, 1789 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31387-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31387-2