Abstract

Histopathological image analysis plays a critical role in modern medical diagnostics, particularly in the detection and classification of various types of cancer. This study proposes a method called HistoDARE (Histopathology-Aware DINO with Attention-based Representation Enhancement), which offers an innovative approach to the attention module used in the Vision Transformers architecture. Unlike conventional attention mechanisms, HistoDARE introduces a novel three-stage AttentionWrapper module that sequentially applies spatial and channel attention followed by a residual refinement stage, enabling the extraction of spatially-aware and semantically distinctive feature representations. HistoDARE is a method integrated into the DINOv2 model, which uses the ViT-L/14 architecture. The obtained features were interpreted using Logistic Regression, and 5-fold stratified cross-validation was applied on the NCT-CRC-HE-100K dataset. The proposed HistoDARE achieved a mean accuracy of 98.03%, precision of 98.03%, recall of 98.02%, F1-score of 98.02%, and specificity of 99.95%, outperforming the baseline DINOv2 and other state-of-the-art methods. The experiments were conducted on a computer with high computational capacity. Based on the DINOv2 architecture, the proposed HistoDARE maintains comparable computational efficiency and resource usage while generating more contextually enriched and discriminative feature representations. During performance measurements, it demonstrated consistent and stable improvements across all stages in all folds. Notably, significant performance improvements were achieved in clinically critical classes such as NORM and STR. These results demonstrate that HistoDARE not only achieves high overall accuracy but also provides superior class-level consistency, making it a robust and generalisable framework for clinical histopathology applications. The developed method has been shared on our GitHub repository. This ensures transparency in terms of reproducibility and supports its usability by other researchers on different datasets in the future. The core contribution of HistoDARE is a three-stage AttentionWrapper (spatial, channel, residual refinement) integrated into the DINOv2 ViT-L/14 backbone to make patch-level representations histopathology-aware. Despite the small numerical gain over a strong self-supervised baseline, this attention-enabled refinement yields statistically consistent improvements on clinically sensitive classes (NORM, STR) and thus strengthens the model’s potential usability in real pathology workflows.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is among the most common diseases worldwide today1. According to global colorectal cancer (CRC) statistics, this disease ranks third among all cancers and accounts for approximately 10% of total cases. In 2020, the number of new cases across all genders and age groups represented 10% of all cancers, while the mortality rate was 9.4%1. These data emphasize that colorectal cancer is a significant global health issue, especially given its increasing incidence with age and lifestyle factors. However, diagnostic processes remain partially manual and observation-based at clinical and pathological levels, leading to variability and delayed results. The difficulty in detecting the disease at an early stage also negatively affects treatment response and survival rates2.

Colorectal cancer originates from epithelial cells in the colon or rectal mucosa, often through polyp formation. While hyperplastic and inflammatory pseudopolyps carry a low malignancy risk, adenomatous and villous adenomas present a significantly higher risk3. Environmental, genetic, and lifestyle factors-such as age, diet, obesity, and smoking-play a major role in its development4,5,6. Most CRCs are adenocarcinomas, but other subtypes such as neuroendocrine or stromal tumours may also occur7.

The time required to obtain definitive results from histological findings and cancer staging, as well as the interpretability of these findings, can directly affect diagnostic accuracy8. For this reason, recent developments in digital pathology have enabled the production of large volumes of visual data by scanning tissues at high resolution and transferring them to a digital environment. These high-resolution layered visuals, known as whole slide images (WSI), can reach gigapixel scale9.

Despite the advances in digital pathology, histopathological image interpretation still faces key challenges such as inter-observer variability among pathologists, the extremely large scale of whole slide images (WSI), and the need to localize diagnostically relevant tissue regions with precision. These challenges reduce the reproducibility and consistency of pathological diagnoses. Therefore, there is an urgent need for AI-based methods capable of precise feature localization and context-aware analysis. The proposed HistoDARE framework aims to address these diagnostic and technical challenges by enhancing the representation quality of histopathological features.

However, this volume of data is becoming unusable for manual analysis, thereby increasing the demand for automated systems10. The need for automation in the management of digital pathological data is growing, and artificial intelligence technologies are increasingly being used in the early diagnosis and detection of colorectal cancer. In endoscopic screenings, AI-supported real-time systems have succeeded in detecting adenomatous polyps with higher accuracy11. These systems analyse colonoscopy images and immediately flag abnormal lesions, preventing small lesions from being overlooked.

Artificial intelligence systems not only detect lesions but also assist clinical decision-making by distinguishing between benign and malignant tissue. Such innovations improve diagnostic accuracy and contribute to the standardisation of endoscopic procedures. In this context, integrating AI into CRC screening offers a promising approach to increase early diagnosis rates and establish effective healthcare systems12. Moreover, mortality rates decrease significantly when CRC is detected at an early stage. Computer-based decision support systems thus play a decisive role in diagnosis and treatment planning, enhancing accuracy and reducing human dependency.

Although classic deep learning techniques yield effective results in many healthcare applications, they still exhibit structural limitations. Models trained for specific tasks lack generalisation capacity and require repetitive data preparation and labelling processes, which are resource-intensive. Especially in histopathological image analysis, manual annotation demands significant expert effort, making traditional supervised methods unsustainable in large-scale practice.

Self-supervised learning (SSL) introduces an important innovation by enabling representation learning from unlabelled or sparsely labelled data. Since histopathological image labelling is costly and time-consuming, SSL enables effective feature extraction with minimal supervision. It learns semantic and structural patterns in unlabelled datasets, facilitating robust performance in classification, segmentation, and anomaly detection.

However, existing Vision Transformer (ViT) and SSL-based models have certain limitations when applied to histopathological image analysis. These models typically assign equal importance to all image patches, potentially overlooking subtle yet diagnostically critical morphological cues. Furthermore, most SSL-based ViT frameworks lack an adaptive mechanism to selectively enhance region-specific or contextually important features. This limitation reduces both interpretability and clinical reliability. To overcome these challenges, our study introduces a targeted attention mechanism designed to enhance the most informative spatial and channel-level representations. Conventional ViT-based SSL models assign nearly uniform importance to all patches, whereas histopathology images typically contain sparse, small, and diagnostically dominant regions. Our goal in this study is to adapt DINOv2 to this setting by explicitly re-weighting spatially informative patches and their channels and by demonstrating this effect through attention visualizations. The present work therefore focuses on patch-level colorectal histopathology classification as a step toward WSI-level analysis.

In recent years, fundamental models (FM) have been trained on billions of images using SSL, providing high-generalisation capabilities that enable transfer learning across medical tasks. Vision Transformers (ViT) stand out as powerful analysis tools for histopathological data by dividing images into smaller patches and modelling spatial relationships via self-attention. When combined with SSL-based representations, these capabilities offer high accuracy and generalisation capacity in critical tasks such as cancer diagnosis13.

Beyond colorectal cancer, recent research has demonstrated the growing effectiveness of deep learning and attention-based transformer frameworks in various medical imaging applications. For example, a grid search-optimized multi-CNN ensemble was used for automated cervical cancer diagnosis, achieving robust feature extraction and classification performance14. Similarly, a hybrid transformer–CNN model was proposed for multi-class skin lesion analysis, illustrating how attention modules improve lesion localization and generalization15. In the neuro-oncology domain, both attention-fused and lightweight feature-fusion networks have been effectively applied to brain tumor diagnosis, highlighting the power of attention mechanisms in identifying critical visual biomarkers16,17. These studies collectively demonstrate that the methodological principles underlying HistoDARE can generalize to other medical and disease-specific imaging tasks, supporting its potential clinical adaptability across different diagnostic scenarios.

To address these limitations, we propose HistoDARE (Histopathology-Aware DINO with Attention-based Representation Enhancement), a novel framework that integrates a multi-stage attention module into the DINOv2 foundation model. HistoDARE adaptively emphasizes diagnostically relevant regions and refines their representation through spatial and channel-level attention, resulting in more interpretable and discriminative features. This approach enhances model explainability and clinical applicability while maintaining computational efficiency. Additionally, by making the full implementation publicly available, HistoDARE promotes reproducibility and supports future research across diverse histopathological datasets.

The following points can define the novelty of this work:

-

An Attention module has been added to the DINOv2 architecture to enable effective feature extraction from histopathological images. The developed AttentionWrapper component performs calculations at both the spatial and channel levels to highlight critical information for classification.

-

The proposed approach offers a highly explainable yet computationally efficient representation learning strategy. Based on the ViT-L/14 architecture, the DINOv2-based AttentionWrapper preserves the model’s strong feature extraction capability while making classification decisions more understandable through the explainable structure of the attention module.

-

The developed method is available to everyone at https://github.com/MRV-1/HistoDARE. This ensures transparency in terms of reproducibility and allows for easy testing of its applicability on different datasets.

Related work

Self-supervised and foundation model paradigms have enabled robust feature learning from large-scale unlabelled histopathology data. The HistoSSL framework introduced a multi-branch structure that learns global, cellular, and staining-level representations18. This approach effectively reduced the annotation burden and achieved a k-NN accuracy of 94.09% on NCT-CRC-HE-100K; however, it still exhibits limited morphological interpretability and lacks spatial explainability in clinical contexts. Similarly, Ikezogwo et al. proposed MMAE, which extends the masked autoencoder paradigm by integrating H&E and RGB modalities19. Although this dual-modality strategy enhanced the learning of histomorphological features and achieved 92.3% accuracy, the need for multi-stain alignment and modality balancing increases model complexity. Song et al. proposed a CycleGAN-based nucleus-aware SSL framework that enables unpaired image translation between staining domains20. While the bidirectional structure improves feature transferability, its dual-generator–discriminator design increases computational cost and training instability. These studies collectively show that while SSL models significantly reduce the need for expert annotations, they often face challenges in interpretability, scalability, and computational efficiency. Addressing these limitations, HistoDARE integrates a lightweight attention mechanism into the foundation-model backbone to preserve feature richness while maintaining clinical interpretability and computational efficiency.

Transformer-based models have become central to medical image understanding due to their ability to capture long-range dependencies. Zhang et al. proposed TransFuse, which fuses CNNs and Transformers in parallel to combine local and global representations for medical segmentation21. Although it achieves superior accuracy with fewer parameters, its dual-branch fusion still increases inference complexity. Lin et al. developed DS-TransUNet, incorporating Swin Transformer blocks in both encoder and decoder22. This dual-scope design enhances global context modelling but raises training cost and memory consumption. Pan et al. further introduced EG-TransUNet with attention-guided enhancement modules23, achieving 93.44% mDice on colorectal cancer segmentation; however, the authors note that broader clinical validation remains necessary. Fitzgerald et al. extended this line with FCB-SwinV2, replacing the Transformer branch with a SwinV2-based architecture24, achieving mDice 95.77% and mIoU 91.88%-but with considerable model depth and hardware demand. Beyond segmentation, Venkatraman et al. proposed SAG-ViT, combining multi-scale EfficientNet features with graph attention networks to refine patch-level embeddings before Transformer encoding25. While this hybrid design improves F1-score to 98.61% on NCT-CRC-HE-100K, its multi-stage pipeline introduces high computational overhead and structural complexity. Likewise, recent biomedical segmentation models such as BioSAM-226 and SAM-2-based adaptations27,28,29 demonstrate remarkable zero-shot generalization but depend heavily on user interaction or dataset-specific fine-tuning, limiting their automation potential. In addition, several studies explored attention-enhanced lightweight architectures, further illustrating the trend toward hybrid transformer–CNN fusion. Bilal and Asif introduced a feature-level fusion model with a self-attention mechanism for brain tumor classification, achieving 98.55% accuracy while maintaining high efficiency, yet its performance remains dataset-specific and may require further validation on histopathological images17. Similarly, Hekmat developed an attention-fused architecture for brain tumor diagnosis that combines convolutional and transformer-based attention layers to improve interpretability and diagnostic performance, though the sequential fusion design increases model complexity16. HistoDARE, in contrast, leverages a three-stage attention module directly within a foundation model backbone, balancing representational power and efficiency without additional fine-tuning layers or user intervention.Unlike multi-branch or multi-stage models such as TransFuse, DS-TransUNet, or SAG-ViT that require multi-level feature fusion and heavy computation, HistoDARE operates as a single unified module directly integrated into DINOv2 without additional training stages. This enables lower complexity and faster inference while maintaining interpretability.

The NCT-CRC-HE-100K dataset has been a benchmark for numerous histopathological classification studies. Al.Shawesh et al. employed a ResNet-50 CNN with transfer learning, achieving 99.9% accuracy30, though the model’s reliance on full supervision restricts scalability. Kumar et al. proposed CRCCN-Net, a lightweight CNN achieving 96.26% accuracy with reduced computational demand31, but its limited representational depth constrains performance in complex tissue morphology. Sun et al. classified tissues as benign or malignant with 94.8% accuracy32, while Peng et al. enhanced ResNet50 through fine-tuning only the final layer to achieve 99.99%33. Despite high accuracies, these CNN-based methods depend heavily on large-scale annotations and lack cross-domain generalization. Ensemble and hybrid CNN approaches such as Color-CADx34 and DenseNet–ResNet hybrids35 achieved accuracies above 99%, yet their performance is bounded by color and stain variation sensitivity inherent to supervised pipelines.

Recent state-of-the-art models on the NCT-CRC-HE-100K dataset have achieved accuracies approaching 98%, establishing a high performance ceiling for colorectal histopathology classification. While these advances demonstrate remarkable progress, they still reveal notable trade-offs between accuracy, computational efficiency, and adaptability. For instance, the high computational cost of multi-stage Transformer–GAT pipelines25, the dependency on user interaction for achieving optimal segmentation27, and the limited generalizability of biomedical-specific segmentation frameworks26 illustrate the persistent challenges in achieving both automation and scalability. The novelty of HistoDARE lies in introducing a hierarchical attention refinement (spatial + channel + residual) within a self-supervised foundation model, DINOv2 ViT-L/14. This design preserves the generalization power of DINOv2 while injecting histopathology-aware focus through learnable attention refinements at multiple representational levels. Building upon these advancements, HistoDARE aims to extend this performance ceiling by integrating a hierarchical attention mechanism within the DINOv2 backbone to enhance spatial and channel-level feature refinement. This design leverages foundation-model representations while addressing prior limitations through improved interpretability, reduced dependence on manual tuning, and balanced computational efficiency suitable for clinical-scale applications. To enhance readability and clarify the position of HistoDARE within existing attention-based frameworks, we incorporated a comparative summary in Table 1 that contrasts representative models in terms of backbone, attention type, and main limitations. A detailed quantitative comparison of these works on the NCT-CRC-HE-100K dataset is presented in Table 8 under the Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods section.

Methodology

Overall architecture of HistoDARE

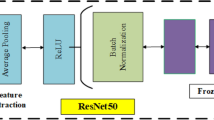

This study presents HistoDARE (Histopathology-Aware DINO with Attention-based Representation Enhancement), a new approach that aims to classify images by extracting meaningful representations from histopathological images. At its base is the DINOv2 architecture, which stands out for its powerful feature extraction capabilities. An AttentionWrapper module developed specifically for the DINOv2 architecture has been integrated. Figure 1 shows the process presented in the architecture, which begins with images undergoing a standard pre-processing stage. In this stage, all images are scaled to 256\(\times\)256, cropped to 224\(\times\)224 from the centre, and normalised to make them suitable for the model.

The prepared images are fed into the pre-trained DINOv2 network in a self-supervised way to obtain patch tokens from the intermediate layers. These intermediate representations are transferred to the AttentionWrapper module to obtain more focused feature vectors. Within this module, spatial and channel attention are applied in order, and the output representation is simplified with residual connection and global mean pooling steps. Each stage in the attention module added to the proposed architecture serves to understand the importance of the weights of the extracted feature vectors.

These compact feature vectors are standardised and then classified using a logistic regression model. During the training phase, the data set is divided into 60% train, 20% validation, and 20% test, and 5-fold stratified cross-validation is applied to the train part. The model’s performance is evaluated using many metrics, such as accuracy, precision, sensitivity, F1-score, specificity, and class-based accuracy.

Additionally, dimension reduction was performed on the extracted features using PCA, followed by t-SNE to make them expressible in a two-dimensional plane, and clustering was performed by determining the class centres using K-Means. The visual distributions of the representations were examined through these steps. This integrated approach aims not only to increase accuracy compared to the DINOv2 architecture but also to make the model’s decision-making process more understandable.

Dataset description and preprocessing

This study is based on the NCT-CRC-HE-100K dataset created in collaboration between the National Cancer Centre (NCT) in Germany and Mannheim University Hospital36. Figure 2 shows selected sample images from the dataset. The dataset used in this study is a collection of 100,000 colour images consisting of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained colorectal tissue sections. All images are fixed at a size of 224\(\times\)224 pixels and are positioned so that each belongs to only one class. The sections, classified by expert pathologists, are distributed across nine separate histological categories. The dataset provides an extremely suitable infrastructure for training processes by maintaining numerical balance between classes.

The pre-processing stages are based on classic steps commonly used in Vision Transformer-based models. No complex image processing techniques were used at this stage; instead, standard procedures were preferred to ensure compatibility with the model’s input layer. The visual segments were first resized and then cropped to 224\(\times\)224 using the centre crop method. To be compatible with the model’s pretrained weights, each image was normalised separately for each of the three colour channels. The mean and standard deviation values of ImageNet, which are widely accepted, were used as a reference in the normalisation stage. The data pre-processing applied in this stage ensures visual consistency while enabling the transformer-based model in the proposed architecture to work more effectively.

Feature extraction using DINOv2

In this study, the DINOv2 model was used as the basic feature extraction tool. DINOv2 is a visual representation model developed based on self-supervised learning and trained using large datasets. The DINOv2 architecture makes it possible to obtain powerful and general feature sets even when limited label information is available. The accuracy performance of the representations produced by such a model significantly improves in datasets with high variance and detail, such as histopathological images.

Within the scope of the study, the ViT-L/14 architecture of DINOv2 was used, and the pretrained version of the model on ImageNet was utilised. This saved training time and enabled more robust and generalisable representations to be obtained through transfer learning. The get_intermediate_layers function, which provides access to the inner layers of the ViT architecture, was used in the feature extraction stage. It is worth noting that the function get_intermediate_layers is not a custom modification but a built-in utility provided in the official DINO/DINOv2 ViT implementation, designed to extract patch-wise representations from selected transformer blocks. We only use it to retrieve the final-layer patch tokens excluding the [CLS] token. Patch tokens were extracted from the final (24th) encoder block of the ViT-L/14 backbone using the get_intermediate_layers(x, n=1, return_class_token=False) configuration, which provides semantically rich and spatially coherent features optimal for the subsequent attention-based refinement process. This function enables the extraction of patch-wise representations corresponding to each patch except for the class token, thereby allowing the acquisition of both global and local information structures.

The model’s output consists of 1024-dimensional embedding vectors for each patch. These high-dimensional representations are used for more detailed analysis in the classification and visualisation stages. Thus, DINOv2’s rich and layered representation capability has been adopted as the fundamental building block of the research. Feature extraction was performed on the final transformer layer of DINOv2, as it captures semantically rich and diagnostically relevant representations. Earlier layers generally encode lower-level color and texture cues, which are less discriminative for histopathological decision-making. Therefore, using the final layer ensures that the extracted features align with high-level morphological semantics required for classification.

The DINOv2 backbone was kept frozen during training to preserve the pretrained self-supervised representations and to ensure computational efficiency. The proposed AttentionWrapper refines these frozen embeddings through learnable spatial and channel-level attention without additional fine-tuning of backbone parameters.

AttentionWrapper module

The pseudocode for the AttentionWrapper module introduced in this study is provided in Algorithm 1. The goal is to transform patch-based features obtained from a basic visual transformer model into more meaningful and discriminative representations by processing them at both the spatial and channel levels. In particular, such attention mechanisms contribute to highlighting information-rich regions in histopathological images containing tumour tissue.

The model first calculates an importance value for each patch using a spatial attention network and reweights the features using these values. In the second stage, a channel-level summary is created by taking the average of all patches, and the channel attention mechanism is applied using the weights obtained from this summary. Dropout and residual connections are used to balance the risk of overfitting during the model’s learning phase; ultimately, a fixed-size output is obtained using the global mean pooling.

Spatial attention

Intuitively, the spatial attention module learns to identify and assign higher importance to image patches that contain diagnostically relevant regions such as tumor boundaries or glandular textures while suppressing less informative background areas.

The mathematical symbols used in the subsequent formulas are summarized in Table 2.

The spatial attention mechanism we propose to determine the importance of each patch within its own context is implemented using a Multilayer Perceptron structure. This structure consists of a linear layer, a GELU activation function, Layer Normalisation, and a second linear transformation step. Thanks to the sigmoid function applied to the output, the attention value of each patch is normalised to the range [0,1] and learned. These operations are described in Equations 1 and 2.

Equation 1 and Equation 2 aim to weight the textures in each patch according to their level of importance. The critical part of the image will be given a high weighting, while the image region of low importance will be suppressed.

Channel attention

The second component of the proposed attention mechanism, channel attention, focuses on determining the importance of each feature channel for classification. This structure is similar to the Convolutional Block Attention Module37 approach. However, it has been restructured in line with the logic of Transformer-based models. In simpler terms, the channel attention mechanism determines which feature channels capture the most salient morphological cues, such as color intensity, cellular density, or structural variation, and amplifies them to enhance diagnostic discrimination.

First, global mean pooling is applied over the spatially weighted output \(F_s\) to obtain the channel representation \(\bar{F}_c\):

This vector is passed through a two-layer MLP structure to calculate the attention score for each channel:

Here, \(W_3 \in \mathbb {R}^{C \times C/r}\) and \(W_4 \in \mathbb {R}^{C/r \times C}\) define the MLP weights, and the reduction ratio \(r = 16\) is typically selected. \(\textrm{GELU}\) serves as a non-linear activation function. \(\sigma\) compresses the attention value of each channel into the range [0, 1] using the sigmoid function.

The reduction ratio \(r = 16\) was selected as it provides an effective trade-off between computational efficiency and representational capacity. Lower ratios (e.g., 4 or 8) increase model size without notable performance gain, while higher ratios (e.g., 32) risk losing critical channel-level variation. This choice is also strongly supported by prior work: widely used attention architectures such as SENet38, CBAM37, and EfficientNet39 all adopt \(r = 16\) as the default and empirically validated reduction ratio. These studies demonstrate that \(r = 16\) provides an optimal balance between parameter efficiency and channel expressiveness without introducing additional computational overhead, and therefore collectively justify its selection in our design.

The attention-based scoring obtained is multiplied by the original spatial attention output \(F_s\) to calculate the rescaled channel-based final feature map \(F_{sc}\):

With this mechanism, the model learns to highlight channel representations with high semantic density while suppressing those with low density. Especially in structures that perform global feature learning, such as ViT, modelling channel relationships in this way contributes significantly to overall performance.

Combined attention output

The spatial and channel attention components calculated in the previous steps work together to identify prominent regions at both the spatial level and the channel level. Thanks to the combination of these two mechanisms, the model is able to distinguish between spatially and contextually rich features.

In the final step, a residual connection is added to the rescaled feature map \(F_{sc}\) obtained after channel attention, thereby enhancing the model’s learning capacity. Additionally, the dropout application described in Equation 6 is also performed in this step.

This expression preserves the useful information provided by the attention mechanisms, ensures the sustainability of the original feature vector within the model, and reduces the risk of overfitting.

Before moving on to the classification head of the model, the output of the attention mechanisms, \(F_{\text {out}}\), is reduced to a fixed-size vector. At this point, the proposed architecture is customised differently from traditional ViT architectures. While the ViT architecture uses the [CLS] token as a classification representation, the proposed method evaluates the contribution of all patches equally at the relevant stage. For this purpose, global mean pooling is applied on the spatial dimension in Equation 7.

To support the explainability claim, spatial attention weights from the AttentionWrapper were averaged across channels and projected back onto the input image space. The resulting attention heatmaps were normalized, upsampled to match the input resolution, and overlaid with transparency (alpha = 0.5) to visualize diagnostic focus regions. Example visualizations of these attention heatmaps for NORM, STR, and TUM classes are provided in Figure 3.

Representative attention heatmaps generated by the proposed HistoDARE model. Each column corresponds to one histopathological class-Normal (NORM), Stromal (STR), and Tumor (TUM)-and each row presents two representative patches per class. The overlaid heatmaps (transparency \(\alpha =0.5\)) demonstrate that HistoDARE selectively attends to diagnostically informative epithelial and stromal regions.

Global Mean Pooling (GMP) was adopted instead of relying on the [CLS] token because histopathological tissue images lack a single dominant spatial center of information. GMP ensures that all patches contribute equally to the final representation.

Although we do not include a dedicated ablation for this component, prior work in transformer-based vision models has shown that GMP often produces more stable and less noise-sensitive representations than the [CLS] token, especially in patch-based domains such as histopathology. Therefore, GMP provides a more consistent aggregation mechanism for distributed morphological cues.

Equality 7 represents the total number of patches N, the batch size B, and the number of channels C. Thus, the z vector provides a more global and semantically rich representation that encompasses information spread across the entire image, rather than just a specific location.

This approach is an important contribution that HistoDARE brings to the literature. HistoDARE produces an attribute representation that is derived from the entire image and carefully enriched at both the spatial and channel levels. Thus, the model can make decisions that are not only based on superficial structures but also on contextual relationships. In the final stage of the proposed attention mechanism, unlike classical transformer architectures, the mean pooling stage aims to ensure that all patches contribute to the feature vector to be created.

Classification stage

The features extracted with HistoDARE were evaluated using a Logistic Regression model for classification. Logistic Regression was preferred due to its simple and easy-to-interpret structure and its resistance to overfitting. Before classification, the features were normalised with StandardScaler to eliminate differences between measurement scales.

To enhance the model’s reliability, 5-fold stratified K-Fold cross-validation was performed, and the results are presented in Section 6. For each fold, the basic classification metrics of Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Specificity were calculated. After the training and validation stages of the model, a final performance evaluation was also conducted on a separate test set.

All experiments were implemented in Python 3.10 using PyTorch 2.5.1+cu118, torchvision 0.20.1, and scikit-learn 1.3.2. Supporting libraries included NumPy 1.26, Matplotlib 3.8.1, and Timm 1.0.15. These versions were fixed across all experiments to ensure reproducibility.

Experiments and results

Implementation details

The hyperparameters in Table 3 are determined according to the ViT-L/14 architecture of DINOv2. The model examines patch-based input images, each with a size of 224 \(\times\) 224 pixels, and performs representation learning on patches of 14\(\times\)14 pixels each. The resulting embeddings are 1024-dimensional. The Transformer architecture consists of 24 layers, each containing 16 multi-head attention heads. A 4.0-fold expansion is applied in the MLP block, while the dropout rate is set to 0.1 to prevent overfitting.

The model’s training and testing processes were performed on a powerful machine. This system includes a 12th Generation Intel Core i9-12900K processor, 128 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 graphics card. The RTX 4090 offers high computational performance on large datasets with 16,384 CUDA cores and 24 GB of GDDR6X memory. This hardware enables large-scale images to be processed quickly and ensures that the attention block added to the DINOv2 model extracts features efficiently and effectively.

Computational complexity and resource usage

Table 4 provides comparative values for system usage and complexity metrics in the feature extraction process for the DINOv2 and HistoDARE models. In terms of model complexity, DINOv2 has a FLOPs value of 77.89 GMac, while the HistoDARE model operates at 78.42 GMac. The number of parameters was measured as 304.37 million for DINOv2 and 306.60 million for HistoDARE. The feature extraction time was recorded as 2080.08 seconds for DINOv2 and 2097.84 seconds for HistoDARE.

In terms of system resource usage, CPU RAM usage before feature extraction was 1.71 GB (3.80%) and 21.34 GB (35.40%), respectively, GPU VRAM usage was 1911 MB (11.66%) and 15542 MB (94.86%), and the maximum CUDA memory allocated by PyTorch was measured as 1753.22 MB and 8257.58 MB, respectively.

After feature extraction, CPU RAM usage was 2.42 GB (5.00%) for DINOv2, 21.58 GB (35.80%) for HistoDARE, GPU VRAM usage was 2471 MB (15.08%) and 15542 MB (94.86%), respectively, and the maximum CUDA memory allocation was recorded as 1640.45 MB and 8058.91 MB. The difference in values between the two blocks is shown in the Change column.

While this increase in GPU and memory utilization reflects the added complexity introduced by the hierarchical attention layers, it also represents a typical trade-off between enhanced representational quality and computational demand. Importantly, the overall increase remains within acceptable limits for modern clinical-grade workstations commonly used in digital pathology workflows. Nevertheless, this dependency on higher resource consumption is acknowledged as a limitation of the current implementation, and future work will focus on model compression and attention pruning strategies to optimize deployment efficiency without compromising diagnostic accuracy.

Evaluation metrics

In this section, various metrics commonly used to evaluate the attributes generated by the model are examined. Each metric helps to analyse the overall performance more comprehensively by evaluating the model from specific angles. The metrics used are Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Specificity40.

Confusion matrix analysis

Figure 4 shows the complexity matrices for DINOv2 and the proposed HistoDARE architecture. The prediction performance of both methods is compared based on the number of correctly and incorrectly predicted examples for each class. This allows the performance differences between the models for each class to be clearly observed. The complexity matrix also highlights that the HistoDARE method outperforms DINOv2 in distinguishing ADI, DEB, NORM, and STR tissues.

Ablation study

Table 5 compares the classification performance of DINOv2 and the proposed HistoDARE method using 5-fold cross-validation. The evaluation metrics are presented in Section 3. Analysis of the results shows that both DINOv2 and HistoDARE achieve high accuracy. However, the HistoDARE method provides a small but consistent improvement in performance in all metrics. Notably, the increase in accuracy and precision rates to 98.03% indicates that the model further minimises classification errors and the risk of misclassification.

Maintaining a low error rate in histopathological image analysis is crucial for ensuring the reliability of clinical decision support systems. Therefore, the performance improvement of between 0.1% and 0.11% offered by HistoDARE is significant, both in terms of the metrics and in practice. Furthermore, the model’s consistent improvement across all metrics indicates a balanced and stable structure.

These findings strengthen the potential of HistoDARE for use in areas requiring high precision, such as histopathological image analysis, and demonstrate that it can complement existing DINOv2-based approaches.

Table 5 presents the results of the ablation study conducted to evaluate the individual and combined contributions of the spatial and channel attention mechanisms within the proposed HistoDARE framework. In this experiment, three configurations were analysed separately: DINOv2 with only spatial attention, DINOv2 with only channel attention, and the full dual-attention (spatial + channel) HistoDARE model.

Although the addition of the channel attention branch did not lead to a visible numerical improvement in the 5-fold averaged results compared to the spatial-only configuration, statistical analysis revealed significant differences in key metrics such as accuracy (\(p = 0.0482\)), recall (\(p = 0.0470\)), and specificity (\(p < 0.0001\)). Precision (\(p = 0.0622\)) and F1-score (\(p = 0.0620\)) exhibited marginal significance, indicating a consistent but subtle trend in favour of the dual-attention configuration. These findings suggest that the channel attention mechanism contributes to inter-channel feature calibration and overall model stability rather than direct performance increase. In particular, the improvement in specificity demonstrates that the combined attention structure effectively reduces false-positive predictions, which is crucial in clinical histopathological classification where diagnostic precision and reliability are of paramount importance.

Although the mean metric improvements from adding channel attention appear marginal in Table 5, a paired t-test across 5-fold cross-validation splits revealed statistically significant differences in Accuracy (\(p=0.0482\)), Recall (\(p=0.0470\)), and Specificity (\(p<0.0001\)). This indicates that channel attention contributes primarily to variance reduction and model stability rather than direct accuracy gains. Therefore, the statistical significance arises from improved robustness and consistency across folds, rather than large mean shifts.

Explainability and visual evidence

To support the explainability claim, spatial attention heatmaps generated by the proposed AttentionWrapper were projected back onto the input image space and overlaid with transparency (alpha = 0.5). As shown in Figure 3, the highlighted regions correspond to diagnostically informative epithelial, stromal, and tumor structures. These visualizations confirm that HistoDARE consistently focuses on clinically meaningful areas, demonstrating that the model’s attention mechanism aligns with pathologist-identified morphological cues. This provides direct visual validation for the interpretability of the proposed approach.

Cross-validation performance

In order to ensure the reliability of the metrics obtained in the evaluation phase, 5-fold stratified cross-validation was preferred. Cross validation is a widely used structure to measure the generalisation capacity and consistency of the model.

The reason for choosing the number of k as 5 is both to maintain the train-validation balance and to have a sufficient number of samples in each fold and to keep the computational cost at a reasonable level. Although choosing k as 10 provides small increases in accuracy, it significantly increases the computation time. Histopathological image classification is computationally intensive, and therefore, choosing a k of 5 is a widely accepted choice in the literature.

Stratified cross validation is preferred to prevent the possibility of unbalanced distribution of classes in the dataset. In each fold stage, it is aimed to measure the success of the model in all classes by ensuring that the distribution rates in the classes remain similar to the original dataset. Since there is a possibility of underrepresentation of certain classes in histopathological image types, the stratified structure prevents distribution imbalances.

Table 6 shows the 5-fold cross validation results of DINOv2 and the proposed HistoDARE method. When the results are analysed by fold, it is seen that HistoDARE provides a consistent accuracy compared to DINOv2 at each fold. The most significant increase is observed in the 3rd and 4th folds, with approximately 0.1% and 0.2% increase in these folds.

When the mean values are analysed, it is seen that the HistoDARE model produces higher results than DINOv2 in all basic metrics such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Specificity. In particular, a consistent increase was achieved in each fold. This shows that HistoDARE offers a stable and generalisable structure, not only in general accuracy. This process supports the preference of the model in application areas with low error tolerance, such as histopathological images.

Class-wise accuracy and evaluation metrics

Table 7 shows the class-based accuracy results of DINOv2 and the proposed HistoDARE models in comparison. The accuracy rates of both models on the classes are evaluated separately and the classes in which improvement is achieved are analysed in detail.

When the results in Table 7 are analysed, small but consistent increases were achieved in ADI, DEB, LYM, MUC, MUS, NORM and STR classes. In the BACK and TUM classes, the results of both models are very close to each other and it is observed that the already high accuracy rates can be maintained in these classes. The remarkable improvement is observed in NORM and STR classes. This is also reflected in the confusion matrix in Section 4.3. In terms of clinical applications, these improvements are especially important in classes that are prone to misclassification such as normal tissue (NORM) and stromal tissue (STR).

The results in Table 7 show that HistoDARE offers a stable performance not only in overall accuracy but also in inter-class accuracy. This can be considered as another finding that supports the generalisability of the model and its suitability for clinical use.

Dimensionality reduction and clustering visualization

During the studies, dimensionality reduction and clustering methods were preferred to visualize the discrimination power of the representation features learned by the model between classes more understandably. The high-dimensional visualization was reduced to 30 dimensions in the feature space with Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Then, using the t-SNE algorithm, the dimensions obtained from PCA are shown in a 2-dimensional space. In the next step, using the K-Means algorithm, the natural cluster structure of the features produced by both models was analysed and the final distributions are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 shows the clusters of the features obtained by DINOv2 and HistoDARE methods. When the figure is analysed in detail, it is seen that both methods group the classes similarly and the general distribution overlaps. This shows that both models are able to learn the basic distinguishing features between classes and similar decision structures are formed. Such visualisation studies are frequently preferred in the literature as they reveal the intrinsic representational power of the model. The limited differences are expected when starting from a strong base model such as DINOv2. Although HistoDARE offers small but consistent improvements, it is understood that the basic structure is preserved in the overall clustering mechanism.

Compared to the baseline DINOv2, the t-SNE projections in Figure 5 show that HistoDARE exhibits tighter intra-class clusters and clearer separation between clinically similar classes, particularly between NORM and STR. This indicates that the hierarchical attention refinement helps the model form more discriminative and stable representations, improving class-level separability without compromising generalization.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

The HistoDARE method in Table 8 is presented in comparison with the accuracies of architectures frequently used in the literature. All methods were evaluated on NCT-CRC-HE-100K. When the results are analysed, HistoDARE method shows the highest performance in Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score and Specificity metrics compared to other approaches.

Conclusion

In histopathological images, each pixel in the image has different importance. While some tissues contain tumourous areas, some tissues are classified as normal. However, patches obtained in classical ViT architectures have the same level of importance. HistoDARE has introduced a new approach to the weighting mechanism at this stage. HistoDARE, which we propose in this study, differs from the ViT-L/14 based DINOv2 architecture with an additional attention module. The Attention module achieves this success by differentiating the weighting of features from the basic ViT architecture. The spatial attention mechanism in the Attention module overweights the part of the textures in each patch that is critical for classification and suppresses the low-importance image region. Channel attention, the second component of the proposed attention structure, focuses on determining how important each feature channel is for classification. Thanks to these two components, the model is able to separate both spatially and contextually rich features. In the third and final component of the Attention module, the learning capacity of the model is strengthened by adding a residual link on the rescaled feature map obtained.The CLS token is used as the classification representation in ViT architectures before the classification head that will take place after this stage. HistoDARE differs from the methods in the literature by applying global mean pooling on the spatial dimension. In this way, it was able to evaluate the contribution of all patches equally.

The features obtained from HistoDARE were categorised by Logistic Regression in the classification stage. All these stages were performed on a high-performance machine with 12th Generation Intel Core i9-12900K Processor, 128 GB RAM and NVIDIA RTX 4090 graphics card, 16,384 CUDA cores and 24 GB GDDR6X memory. Thanks to this hardware infrastructure, large-scale images are processed quickly and the Attention block added to the DINOv2 model allows fast and efficient feature extraction. After the obtained studies, it is seen that DINOv2 and HistoDARE have similar computational complexity. Although HistoDARE uses GPU resources intensively during feature extraction, it has shown a similar performance with DINOv2 in terms of processing time. This can be considered as a natural consequence of HistoDARE’s potential to produce richer and more detailed features. The results show that although HistoDARE imposes an additional cost in terms of system resources, it remains within reasonable limits in terms of overall utilisation and offers a suitable alternative for practical applications.

In this study, experiments were performed on NCT-CRC-HE-100K colorectal cancer tissues. In order to ensure the reliability of the model success, 5-fold stratified cross validation was applied. Since increasing the number of folds increases the calculation time and does not provide a high rate of increase in overall success, it was found that the choice of k number 5 was appropriate based on the examples in the literature. The results obtained in the method were measured by Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, Specificity metrics. The prominent methods in the literature are tabulated and detailed. When HistoDARE is analysed on the basis of comparison metrics, it is seen that these methods are more accurate than these methods on the basis of 0.11% achieved a high result. This small but consistent increase in all metrics highlights the contribution of DINOv2. Especially the regular increase in each fold reveals that HistoDARE offers a stable and generalisable structure. When the class-based accuracies were analysed, small but consistent increases were achieved in ADI, DEB, LYM, MUC, MUS, NORM and STR classes. In the BACK and TUM classes, the results of both models are very close to each other and it is observed that the already high accuracy rates can be maintained in these classes. The remarkable improvement is observed in NORM and STR classes. This is also observed in the complexity matrix. In terms of clinical applications, these improvements are important, especially in classes such as NORM and STR, which are open to misclassification. The results obtained in the class-based comparison reveal that HistoDARE offers a stable performance not only in overall accuracy but also in inter-class accuracy. This can be considered as another finding that supports the generalisability of the model and its suitability for clinical use.

Discussion

HistoDARE provides performance improvements over DINOv2 that appear numerically modest but are statistically significant and clinically meaningful. The gains observed in the NORM and STR classes are particularly important, as misclassification of normal tissue may lead to unnecessary biopsies or overtreatment, while accurate identification of stromal regions is critical for understanding tumor–stroma interactions that influence invasion and disease progression. By improving reliability in these challenging categories, HistoDARE enhances not only quantitative metrics but also the potential clinical utility of transformer-based models in digital pathology.

Statistical analysis conducted over stratified 5-fold cross-validation confirms the consistency of these gains, with significant improvements in Accuracy (\(p = 0.0482\)), Recall (\(p = 0.0470\)), and Specificity (\(p < 0.0001\)). The particularly strong significance in specificity demonstrates the model’s ability to reduce false positives-a crucial requirement in histopathological diagnosis to prevent unnecessary interventions. The marginal significance observed for Precision (\(p = 0.0622\)) and F1-score (\(p = 0.0620\)) suggests that future work with more heterogeneous datasets may further clarify improvements in these metrics.

Although HistoDARE largely maintains the computational cost profile of DINOv2, the additional attention module introduces higher GPU memory consumption. This increase is an expected consequence of augmenting a large ViT-L backbone. Nevertheless, the VRAM requirements remain feasible within modern digital pathology research environments equipped with 24–40 GB GPUs.

This study also has certain limitations. Experiments were conducted exclusively on the NCT-CRC-HE-100K dataset, which may limit generalizability across different staining protocols or acquisition conditions. Additionally, the evaluation was performed at the patch level rather than on whole-slide images (WSIs). Integrating HistoDARE into a WSI-level diagnostic workflow would enable assessment under more clinically realistic conditions. The present work also does not include a qualitative failure case analysis; future studies will incorporate expert-driven review of misclassified samples, especially those near class boundaries.

Future research directions include validating the model on multi-center and heterogeneous datasets, extending HistoDARE to WSI-level pipelines for comprehensive colorectal cancer analysis, and exploring model optimization techniques such as attention pruning, parameter-efficient refinement, and lighter backbone architectures (e.g., SwinV2 or SAM-based variants). These advancements will further enhance the scalability, efficiency, and clinical translatability of HistoDARE for practical digital pathology applications.

Data availability

This study used the publicly available NCT-CRC-HE-100K dataset, which can be accessed at: https://zenodo.org/record/1214456 No additional proprietary data were generated or analyzed. All data used in this study are publicly accessible, and the relevant dataset references have been cited within the manuscript.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Sung, H. et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Johnson, G. G. R. J. et al. Colorectal polyp classification and management of complex polyps for surgeon endoscopists. Canadian Journal of Surgery 66, 491–498. https://doi.org/10.1503/CJS.011422 (2023).

Arnold, M. et al. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 66, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1136/GUTJNL-2015-310912 (2017).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 73, 17–48. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21763 (2023).

Clinton, S. K., Giovannucci, E. L. & Hursting, S. D. The world cancer research fund/american institute for cancer research third expert report on diet, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: Impact and future directions. Journal of Nutrition 150, 663–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz268 (2020).

Mármol, I., Sánchez-de-Diego, C., Dieste, A. P., Cerrada, E. & Yoldi, M. J. R. Colorectal carcinoma: A general overview and future perspectives in colorectal cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18010197 (2017).

Edge, S. B., & Compton, C. C. The american joint committee on cancer: The 7th edition of the ajcc cancer staging manual and the future of tnm. Annals of Surgical Oncology 17, 1471–1474 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4.

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Medical image analysis 42, 60–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005 (2017).

Madabhushi, A. & Lee, G. Image analysis and machine learning in digital pathology: Challenges and opportunities. Medical Image Analysis 33, 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2016.06.037 (2016).

Urban, G. et al. Deep learning localizes and identifies polyps in real time with 96% accuracy in screening colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 155(4), 1069–1078. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.037 (2018).

Dekker, E., Tanis, P. J., Vleugels, J. L. A., Kasi, P. M. & Wallace, M. B. Colorectal cancer. The Lancet 394, 1467–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32319-0 (2019).

Dosovitskiy, A., et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. ICLR 2021 - 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (2020).

Bilal, O., Hekmat, A. & Khan, S. U. R. Automated cervical cancer cell diagnosis via grid search-optimized multi-cnn ensemble networks. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics https://doi.org/10.1007/s13721-025-00563-9 (2025).

Bilal, O. An amalgamation of deep neural networks optimized with salp swarm algorithm for cervical cancer detection. Computers in Biology and Medicine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2025.110106 (2025).

Hekmat, A., Zhang, Z., Khan, S. U. R., Shad, I. & Bilal, O. An attention-fused architecture for brain tumor diagnosis. Computers in Biology and Medicine https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2024.107221 (2025).

Bilal, O. & Asif, S.: A lightweight neural network with feature-level fusion and attention mechanisms for brain tumor classification. Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design (2025) https://doi.org/10.1007/s41939-025-00889-x

Jin, X., Huang, T., Wen, K., Chi, M. & An, H.: Histossl: Self-supervised representation learning for classifying histopathology images. Mathematics 2023, 11, 110 11, 110 (2022) https://doi.org/10.3390/MATH11010110

Ikezogwo, W.O., Seyfioglu, M.S. & Shapiro, L.: Multi-modal masked autoencoders learn compositional histopathological representations (2022)

Song, Z. et al. Nucleus-aware self-supervised pretraining using unpaired image-to-image translation for histopathology images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 43, 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2023.3309971 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Liu, H. & Hu, Q.: Transfuse: Fusing transformers and cnns for medical image segmentation 2, 1–11 (2021)

Lin, A., et al.: Ds-transunet: Dual swin transformer u-net for medical image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement. 71 (2022) https://doi.org/10.1109/TIM.2022.3178991

Pan, S., Liu, X., Xie, N. & Chong, Y.: Eg - transunet : a transformer - based u - net with enhanced and guided models for biomedical image segmentation. BMC Bioinformatics, 1–23 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-023-05196-1

Fitzgerald, K., Bernal, J., Histace, A. & Matuszewski, B.J.: Polyp segmentation with the fcb-swinv2 transformer. IEEE Access PP, 1 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3376228

Venkatraman, S., Walia, J.S., R, J.D.P.: Sag-vit: A scale-aware, high-fidelity patching approach with graph attention for vision transformers (2024) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-025-02043-z

Yan, Z., et al.: Biomedical sam 2: Segment anything in biomedical images and videos (2024)

Mansoori, M., Shahabodini, S., Abouei, J., Plataniotis, K.N. & Mohammadi, A.: Polyp sam 2: Advancing zero shot polyp segmentation in colorectal cancer detection (2024) https://doi.org/10.1109/ICHMS65439.2025.11154309

Xie, W., Willems, N., Patil, S., Li, Y. & Kumar, M.: Sam fewshot finetuning for anatomical segmentation in medical images. Proceedings - 2024 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, WACV 2024, 3241–3249 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1109/WACV57701.2024.00322

Cai, T., Yan, H., Ding, K., Zhang, Y. & Zhou, Y.: Wspolyp-sam: Weakly supervised and self-guided fine-tuning of sam for colonoscopy polyp segmentation. Applied Sciences, 14, 5007 14, 5007 (2024) https://doi.org/10.3390/APP14125007

Al.Shawesh, R. & Chen, Y.X.: Enhancing histopathological colorectal cancer image classification by using convolutional neural network. medRxiv, 2021–031721253390 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.17.21253390

Kumar, A., Vishwakarma, A. & Bajaj, V. Crccn-net: Automated framework for classification of colorectal tissue using histopathological images. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 79, 104172. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BSPC.2022.104172 (2023).

Sun, K., et al.: Automatic classification of histopathology images across multiple cancers based on heterogeneous transfer learning. Diagnostics. 13, 1277 13, 1277 (2023) https://doi.org/10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS13071277

Peng, C.C. & Lee, B.R.: Enhancing colorectal cancer histological image classification using transfer learning and resnet50 cnn model. 2023 IEEE 5th Eurasia Conference on Biomedical Engineering, Healthcare and Sustainability, ECBIOS 2023, 36–40 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1109/ECBIOS57802.2023.10218590

Sharkas, M. & Attallah, O.: Color-cadx: a deep learning approach for colorectal cancer classification through triple convolutional neural networks and discrete cosine transform. Scientific Reports. 14(1), 1–23 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56820-w

Uddin, A.H., et al.: Colon and lung cancer classification from multi-modal images using resilient and efficient neural network architectures. Heliyon 10 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2024.E30625

Kather, J. N. et al. Predicting survival from colorectal cancer histology slides using deep learning: A retrospective multicenter study. PLoS medicine 16(1), 1002730. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002730 (2019).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J.-Y., & Kweon, I.S.: Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 3–19. Springer, Munich, Germany (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G.: Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 7132–7141 (2018).https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745

Tan, M. & Le, Q.: EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In: Chaudhuri, K., Salakhutdinov, R. (eds.) Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 97, 6105–6114. PMLR, Long Beach, California, USA (2019). https://proceedings.mlr.press/v97/tan19a.html

Sokolova, M. & Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Information Processing & Management 45(4), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2009.03.002 (2009).

Qin, Z. et al. Colorectal cancer image recognition algorithm based on improved transformer. Discover Applied Sciences 6, 422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-024-06127-2 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Regnet: Self-regulated network for image classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 34(11), 9562–9571. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3158966 (2022).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J.: Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778 (IEEE, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 .

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K.Q.: Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2261–2269 (IEEE, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2017.243 .

Gao, S.-H. et al. Res2net: A new multi-scale backbone architecture. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 43(2), 652–662. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2019.2938758 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK) for supporting the author Caner Özcan through the BİDEB-2219 International Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Program (grant no. 1059B192300232).

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TUBITAK) under the BİDEB-2219 International Postdoctoral Research Fellowship Program (grant no. 1059B192300232) awarded to Caner Özcan. TUBITAK also supported this study within the scope of 1002-A Short-Term Support Module under project number 125E868.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Ö. conceived and designed the study, conducted all experimental work, acquired and analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript in its entirety. C.Ö. critically reviewed the manuscript, provided substantive feedback, and contributed to revising and improving the final text. V.K.C.B. contributed to maintaining a collaborative research environment and engaged in manuscript discussions. M.S.G. provided general discussions and feedback during the research process, offering valuable perspectives for refinement. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study used publicly available, de-identified histopathological image data from human tissue samples (NCT-CRC-HE dataset). All data were collected with appropriate ethical approval by the original data providers, and no additional ethical approval was required for this secondary analysis. No personally identifiable information or live animals were involved.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ozkan, M., Ozcan, C., Bumgardner, V.K.C. et al. A histopathology aware DINO model with attention based representation enhancement. Sci Rep 15, 45083 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31438-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31438-8