Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the top infectious disease killers worldwide. It is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and spread through the air, posing a serious threat to vulnerable populations, especially those with weakened immune systems. These challenges emphasize the need for more robust and realistic modeling approaches to inform policy and intervention. This study has been carried out using a fractional-order TB model in Kenya incorporating the Caputo derivative. Fundamental mathematical features such as positivity, boundedness, uniqueness and existence are rigorously investigated for the model. Model parameters, including the fractional order, are estimated, with an optimal value of fractional order around 0.85 yielding the best alignment with real data. A sensitivity analysis, grounded in the basic reproduction number, identifies the influence of critical parameters on disease spread. Visualization through 3D mesh and contour plots further reveals the significant impact of these parameters on TB transmission dynamics. Numerical simulations are conducted by employing the Adams–Bashforth Predictor Corrector scheme, allowing us to account for memory effects and more accurately reflect real-world dynamics. By performing data fitting, we observe that our formulated model produces results that closely match real-world data. Overall, the simulations also explored various intervention strategies, including improved treatment access, faster diagnosis, and recognition of nonlinear transmission dynamics. These results emphasize the importance of timely intervention and provide actionable insights for strengthening TB control policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

TB, caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, continues to be one of the most severe infectious diseases globally. It primarily targets the lungs and transmits via airborne droplets released when an infected individual coughs, sneezes, or engages in close physical interaction. The clinical presentation of the disease includes chronic cough, chest discomfort, weight loss, and fever. Diagnosis typically involves evaluating the patient’s medical history along with various diagnostic tools, including chest radiography and laboratory testing. In low and middle income areas, where access to healthcare is restricted and public health infrastructure is frequently underfunded, the prevalence of TB is particularly high. According to the World Health Organization (2021), a single untreated case of active TB can infect five to fifteen additional people each year, affecting millions of people worldwide. This emphasizes how urgently effective disease management techniques are needed. The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine, along with antimicrobial treatment and antiretroviral therapy, has been widely implemented to curb the spread of tuberculosis. However, despite these interventions, TB continues to pose a serious public health challenge.

Mathematical models have become indispensable tools in epidemiology for comprehending the spread, control, and long-term behavior of infectious diseases. By translating complex biological and social processes into mathematical frameworks, these models help researchers and public health officials predict disease trends, assess the potential impact of interventions, and identify critical parameters influencing transmission dynamics. One of the foundational contributions to TB modeling was made by Castillo-Chavez and Feng1, who introduced a structured compartmental model that explicitly incorporated latent stages of infection. Their work emphasized the distinction between early and late latent TB and analyzed the effects of treating each group on disease dynamics. Shrestha et al.2 proposed a detailed model to analyze the long-term effect of different tuberculosis vaccine types on both disease transmission and the potential evolution of resistant strains. Recent integer-order compartmental models continue to refine TB dynamics by incorporating control strategies.

The use of a fractional order derivative framework introduces memory effects and hereditary properties into the model to capture memory and hereditary effects, offering a more accurate depiction of disease progression and latency compared to classical integer-order models3,4. This approach not only improves the model’s descriptive power but also offers valuable insights for public health planning and resource allocation. For instance, authors in5 proposed a fractional model of HIV interaction with CD4+ T-cells, examining three different fractional-derivative operators to capture complex immune dynamics. In addition to applications,6 analyzed a six-compartment SEIQRD model for COVID-19 in Indonesia. Authors in7 formulated a fractional-order model for the transmission of rabies involving both human and canine populations. Their approach emphasizes the role of memory and non-local interactions in shaping disease dynamics. Yeolekar et al.8 formulated and analyzed a model for infertile couples. Their fractional-order nonlinear model examines the influence of various treatments on infertility by using the Caputo derivative. Recent advancements in epidemiology have highlighted the benefits of using fractal–fractional operators to model systems with both memory and spatial heterogeneity. In9 authors have developed a fractional-order model for tuberculosis transmission using the Caputo derivative and analyzed the system’s qualitative behavior. Their study highlighted the advantages of fractional calculus in providing more accurate and flexible descriptions of disease dynamics compared to classical integer-order models. In10 developed a Caputo fractional-order TB model that incorporated age-structured compartments. Motivated by this growing body of research and the proven effectiveness of fractional calculus in modeling epidemiology, the present study explores a tuberculosis model originally formulated in the integer-order framework, which is then extended using the Caputo fractional derivative. This modification aims to reveal how incorporating memory effects through fractional derivatives enhances the model’s ability to replicate observed data more accurately than its integer-order counterpart.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides essential preliminaries required for the development of the model. In Section 3, the proposed fractional-order tuberculosis model is introduced, along with a detailed explanation of its parameters. Section 4 examines the qualitative properties of the model. Section 5 focuses on proving the existence and uniqueness of solutions, laying the groundwork for further analysis. In Section 6, key model parameters are estimated to align the model with real-world data. Section 7 presents the sensitivity analysis of the basic reproduction number. Section 8 discusses the numerical solution of the model, followed by simulations and graphical interpretations of the results. Finally, Section 9 summarizes the key findings and main contributions of the study.

Preliminary

A summary of essential definitions and properties of fractional calculus is presented in this section to support the forthcoming analysis.

Definition 2.1

11 Let \(\alpha >0\) then for \(x\in [0, b]\), then the Caputo Derivative of function f is:

Definition 2.2

12 The fractional integral of order \(\alpha\) of a function \(f: \mathbb {R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is given by

Definition 2.3

13 The fractional integral of the Caputo fractional derivative of order \(\alpha\) of a function \(f: \mathbb {R}^{+} \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is given by

Lemma 2.4

14 The Caputo Fractional Derivative \({^{C}}{\mathfrak {D}}_{0,t}^{\alpha }\,f(x)\) has the following Laplace transform (L.T.):

Where \(n-1 \le \alpha < n \, \text {and}\,\, F(p) = \mathcal {L}[f(x),p]= \int _{0}^{\infty } e^{-px} f(x)dx\).

Lemma 2.5

15 Let \(f(x)\in [a,b]\) and \({^{C}}{\mathfrak {D}}_{0,x}^{\alpha }\,f(x) \in C[a,b]\) for \(\alpha \in (0,1]\), then by Generalized Mean Value Theorem we get

Where \(a\le \eta \le s, \forall s \in (a,b]\).

Lemma 2.6

The Mittag–Leffler function in generalized form \(E_{p,q}(x)\) for \(x \in \mathbb {R}\) is given by

It can also be written as follows:

Considering the function \(t^{q-1} E_{p, q}(\pm \psi t^{p})\), and taking the Laplace transform, we have

Mathematical model

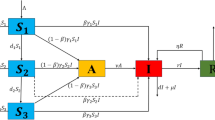

In order to study the spread and management of tuberculosis, we propose a compartmental model that stratifies the total population into six mutually exclusive epidemiological classes: susceptible individuals S(t) who have no prior exposure to TB , vaccinated individuals V(t), who have gained some immunity through vaccination, exposed individuals E(t) who have contracted the infection but they are not yet infectious, infectious individuals I(t) who are exhibiting active symptoms and are capable of transferring the bacteria, individuals undergoing treatment T(t), and recovered individuals R(t) as shown in Fig. 1. Let the total population comprising all the model compartments at time t is denoted by:

The following assumptions underpin the structure of the proposed TB model:

-

All newborns and immigrants entering the population are assumed to be susceptible to TB infection.

-

The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine confers partial protection against TB infection; however, its efficacy is known to diminish over time.

-

The likelihood of reinfection with TB is assumed to be lower than that of primary infection.

Based on the above assumptions, we can now write down the system of differential equations to representing the dynamics of TB following...

To better reflect the complex dynamics and memory effects inherent in the system (7), is generalized to the fractional order version characterized by order \(\alpha\). The fractional order framework using the Caputo derivation is:

With positive initial conditions,

The following epidemiological factors, listed in Table 1 control the development and dynamics of the suggested TB model:

Qualitative properties of the model

Positivity

Theorem 4.1

All solutions of system (8) remain positive for all \(t \ge 0\), provided the initial conditions are positive. That is, the system evolves within the set

Proof

From lemma (2.5) it follows that if for \(x_0 \in [a,b], {^{C}}{\mathfrak {D}}^{\alpha }\,f(x_0) > 0\) then there \(\exists\) a neighborhood \(\mathcal {D}\) of \(x_0\) such that \(f(x)>f(a), \, \forall x \in \mathcal {D}\) and if for \({^{C}}{\mathfrak {D}}^{\alpha }\,f(x_0) < 0\) then there \(\exists\) a neighborhood \(\mathcal {D}\) of \(x_0\) such that \(f(x)< f(a) \, \forall x \in \mathcal {D}\).

Thus, the system’s solution remains positive. \(\square\)

Boundedness

Theorem 4.2

The region

serves as a positively invariant set with respect to the system (8), ensuring that all positive solutions are confined within it over time17.

Proof

On adding all the equations of system (8),

Using L.T. of Caputo Fractional Derivative as discussed in lemma (2.4)

On taking inverse L.T. we get,

Now, by using lemma (2.6) for inverse L.T. we get,

Where, \(c = \Big (\dfrac{\lambda }{\mu } - \chi (0)\Big )\). As \(t \rightarrow \infty\)

Therefore the total population as well as sub-population is bounded. Thus entire solution of the model starts in \(\mathbb {R}_{+}^{6}\) and bounded by the region. \(\square\)

Disease free equilibrium (DFE)

The DFE corresponds to the state where there is no infection in the population, i.e., \(E = I = T = 0\). Setting the right-hand sides of the system (8) to zero and solving under this condition, we obtain:

This equilibrium represents a TB free scenario where the population is distributed among the susceptible and vaccinated compartments only, with no active transmission occurring.

Reproduction number

The expected number of new cases brought on by a single infectious person in a population that is completely susceptible is indicated by the basic reproduction number \((R_0)\). The next-generation matrix approach is employed to calculate \((R_0)\) for the model18. Using this method, the model equations are divided into two matrices: \(\mathcal {V}\), which describes the transitions of individuals between compartments, and \(\mathcal {F}\), which represents the emergence of new infections. Where \(\mathcal {V}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\) are coloumn vectors given by,

At the DFE points, the Jacobian matrices \(\mathcalligra {f}\) and \(\mathscr {V}\) are:

The associated next-generation matrix is written as \(K = \mathbbm {f} * (\mathbbm {v})^{-1}\) that is,

The \(R_0\) is given by the spectral radius of the next-generation matrix, expressed as:

TB can persist and propagate within the population, which could eventually result in higher mortality, when \(R_0\) is greater than one. This emphasizes the necessity of robust and successful public health initiatives to manage the illness. Conversely, if \(R_0\) is less than 1, it indicates that the TB cases will likely to decrease in the future. To avoid a possible re-emergence, continuous monitoring and preventive measures are still essential.

Local stability analysis of the DFE

To analyze the local asymptotic stability of the DFE, we utilize the linearization method explained in19. A DFE is considered locally asymptotically stable if the eigenvalue of the Jacobian matrix are negative or have a negative real part.

Theorem 4.3

Provided that every eigen value of \(J_{\text {DFE}}\) meets the condition \(|arg \lambda _j|\) for \(j=1, 2, 3, \cdots ,\) with \(0 < \alpha \le 1\), then DFE will be locally asymptotically stable.

Proof

The Jacobian matrix of system (8) evaluated at the DFE is given by

where

\(\square\)

The Jacobian can be expressed in a block triangular form as

where

Since \(J_{\text {DFE}}\) is block upper-triangular, its eigenvalues are the union of the eigenvalues of A and C.

The characteristic equation of A is

which simplifies to

The corresponding eigenvalues are

The C matrix can be written in a lower block triangular form:

where,

Therefore, the eigenvalues of C are the union of the eigenvalues of M and P.

The characteristic polynomial of M is

Hence,

where

Since P is lower triangular, its eigenvalues are simply the diagonal elements:

By the Routh–Hurwitz criterion, both roots \(\lambda _{3,4}\) have negative real parts if and only if

The remaining eigenvalues of \(J_{\text {DFE}}\), namely

are all negative. Hence, all eigenvalues of the full Jacobian have negative real parts when \(R_{0}<1\).

For the fractional-order system of order \(\alpha \in (0,1]\), the linearized system \(^{C}\!D_{t}^{\alpha }x = Jx\) is locally asymptotically stable if every eigenvalue \(\lambda\) of J satisfies

Since all eigenvalues of \(J_{\text {DFE}}\) are real and negative when \(R_{0}<1\), the above condition is automatically satisfied for any \(0<\alpha \le 1\).

Therefore, the disease-free equilibrium of system (8) is:

Existence and uniqueness

We address the existence and uniqueness of the solutions associated with tuberculosis disease model (8) using fixed point theorems in this part20,21,22. Let the model (8) with non negative initial values then it can be rewritten as:

An integral transform is applied to both sides, resulting in:

Lemma 5.1

\(\forall\) \(r= 1, 2, \cdots , 6\), The kernels \(\zeta _r\) are satisfying lipschitz condition with lipschitz constants \(K_r\) provided that \(0< K_r <1\).

Proof

We find that for \(S_1\) and \(S_2 \in \mathbb {R}^6_{+}\),

Where \(K_1\) is the lipschitz constant which is contracted. In a similar way,

Where \(K_1= \beta I + \eta +\mu , K_2 = (1- \omega )\beta I +\theta +\mu , K_3 = \rho +\kappa +\mu , K_4= \nu +\mu +\delta , K_5= r +\mu\) and \(K_6= \epsilon \beta I + \phi +\mu\). Thus the kernels \(K_r\) are lipschitz for \(r= 1, 2,\cdots 6.\) \(\square\)

Lemma 5.2

The system(8) has atleast one solution provided that \(\dfrac{t^\alpha K_r}{\Gamma (\alpha +1)}\) for \(r= 1, 2,\cdots 6.\)

Proof

We now define the recursive patterns as follows:

after taking the norm of first equation of equation (13), we get

Similarly we have, \(\Vert \Theta _{rn}(t) \Vert \le \Big (\dfrac{K_r t}{\Gamma (\alpha +1)} \Big )^n \Vert \zeta _r(0) \Vert .\) for \(r= 1, 2,\cdots 6.\)

where, \((\zeta _1, \zeta _2, \zeta _3, \zeta _4, \zeta _5, \zeta _6)=(S, V, E, I, T, R)\). Hence the sequences \(S_n, V_n, E_n, I_n, T_n, R_n\) are uniformly bounded. Now this is to be shown that these sequence converge uniformly to the integral solution (10) over a given interval I which consequenty implies the convergence to the model solutions.

it is clear to see that,

for \(\zeta = (s, V, E, I, T, R)^T\). Hence,

If \(\Big (\dfrac{t^\alpha K_1}{\Gamma (\alpha +1)}\Big )^k <1\) then the above expression converges uniformly on I. Thus by Weirstrass-M test the sequence \(\zeta _n\) is uniformly convergent on I and will have a limit point which is the solution of integral solution (10). Hence the model (8) has atleast one solution.

Theorem 5.3

Model (8) with non negative initial conditions, admits a unique solution provided \(\dfrac{t^\alpha K_1}{\Gamma (\alpha +1)} <1\) is satisfied for each \(r=1, 2, \cdots 6\).

Proof

Suppose that the model (8) possesses two solutions with same initial conditions then the norm of the difference of both solutions can be expressed as:

this inequality is satisfied only if \(S_1 =S_2\). Hence the model (8) will posses a unique solution. Similar argument can be applied for rest of the equations. \(\square\)

Parameter estimation

In this work, the least squares method is utilized to estimate model parameters by minimizing the discrepancy between the numerical solution of the infected population and the observed case data. This fitting process helps bridge the gap between theoretical models and practical epidemiological observations. To perform this estimation, we use MATLAB’s lsqcurvefit function, which provides a robust non-linear least squares optimization technique well-suited for complex, non-linear models like ours23. The fractional-order TB model under consideration includes 13 parameters, capturing various biological and epidemiological processes. Among these, four key parameters \(\beta\)(transmission rate), \(\tau\)( vacciation rate), \(\rho\)(treatment rate for latent TB cases) and \(\nu\)(treatment rate for active TB cases) along with the fractional order are selected for estimation due to their significant influence on disease transmission and treatment dynamics. These parameters are calibrated using tuberculosis case data reported in Kenya from 2000 to 2022 obtained from the World bank24. The data set reports the annual incidence of tuberculosis per 100,000 people. The initial conditions used in both data fitting and the numerical simulations are \(S(0)= 97000, V(0)= 0, E(0)= 2549, I(0)= 451, T(0)=0\) and \(R(0)=0\)16.

To provide a quantitative measure of model accuracy, the root mean square error has been calculated by computing the square root of the average squared differences between predicted and observed data points. We have got the root mean square error of 0.020042 for the Caputo fractional model while it was 0.072408 for the integer order model. This corresponds to a reduction of approximately 72.31 percentage , indicating a substantial improvement in model accuracy. The comparison is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Sensitivity analysis

The purpose of sensitivity analysis, in our disease framework is to determine that which parameters exert the strongest influence to the disease dynamics. It mainly focus on those parameters that can significantly alter the \(R_0\). Sensitivity indices quantify how much the state variable shifts when a parameter changes. These indices can be obtained using the partial derivatives as follows:

The sensitivity indices corresponding to the parameters of this analysis are listed in Table 2. The parameters with negative sensitivity indices effectively reduce disease spread whereas the parameters with positive indices promote the disease transmission. The sensitivity analysis in Fig. 3 indicates that improving the vaccine efficacy \((\omega )\) has the most significant effect in reducing the basic reproduction number \(R_0\). Reducing the transmission rate \((\beta )\) through effective control measures and minimizing the recruitment rate \((\lambda )\) also proportionally decrease \(R_0\). Furthermore, increasing treatment initiation rates for both active and latent TB cases \((\nu , \rho )\), as well as enhancing treatment-related removal \((\delta )\), contributes to lowering disease transmission. Since the progression rate \((\kappa )\) positively influences \(R_0\), interventions that prevent progression from latent to active TB, such as preventive therapy, would further reduce the potential for disease spread.

To enhance the analysis, 3D contour plots illustrating the variation of the basic reproduction number \(R_0\) with respect to the fractional order \(\alpha\) and other key parameters are included. Figure 4 demonstrates that the basic reproduction number \(R_0\) increases with both the transmission rate \(\beta\) and the fractional order \(\alpha\). At higher \(\alpha\) (closer to 1), which indicate weaker memory effects, even a small increase in \(\beta\) leads to a steep rise in \(R_0\). However, for lower \(\alpha\), the system exhibits stronger memory, which dampens the impact of transmission.

The Fig. 5 illustrates that the basic reproduction number \(R_0\) rises as both the recruitment rate \(\lambda\) and the fractional order \(\alpha\) increase. When \(\alpha\) is closer to 1, even slight growth in \(\lambda\) leads to a rapid escalation in \(R_0\). This interplay suggests that memory driven dynamics can mitigate the impact of high recruitment on disease spread.

The Fig. 6 highlights a clear decline in \(R_0\) with increasing natural death rate \(\mu\), especially when the fractional order \(\alpha\) is low. The strongest reduction in \(R_0\) occurs when memory effects are significant lower and \(\mu\) is relatively high. At higher \(\alpha\), this suppressive effect is weaker, indicating that systems with minimal memory retain more disease persistence. The combined effect shows that mortality plays a more effective role in disease control when past states significantly influence the present dynamics.

The Fig. 7 demonstrates that \(R_0\) declines steadily with increasing vaccine efficacy \(\omega\), and this decline is more prominent when \(\alpha\) is lower. In the presence of stronger memory, even moderate improvements in vaccine efficacy lead to notable reductions in disease transmission.

Numerical method

The numerical method for solution of our considered diabetes model is motivated by Adams Bashforth Predictor corrector algorithm25. This approach is well-suited for our model since it provides high accuracy and stability, effectively simulates long-term dynamics, and manages the non-local memory effects of fractional derivatives. Convergence of this method has been rigorously established under the assumptions that the function \(\Omega (t, \zeta (t))\) is Lipschitz continuous and the exact solution is sufficiently smooth. The local truncation error of the method behaves as \(O(h^{1+\alpha })\), where \(h\) is the time-step size. Consequently, the global error satisfies \(|\zeta (t_n) - t_n| = O(h^{1+\alpha })\) for \(0< \alpha < 1\), and the method recovers the classical second-order convergence when \(\alpha = 1\). This fractional-order dependence reflects that smaller values of \(\alpha\) slightly reduce the rate of convergence.

Consider a fractional ordered Initial value problem formulated to solve the model equations is:

Where \(\alpha >0\) and \(t\in [0, T]\). The equivalent voltera integral equation governing the above fractional initial value problem can be stated as:

We discretize the time domain using grid points \({ t_k = kh: k= 0, 1, \cdots , m}\), where \(m \in \mathcal {N}\). To ensure both the accuracy and numerical stability of the solution, a sufficiently small h has chosen. Further, to compute the integral, product trapezoidal quadrature formula is used and hence the corrector formula is given as:

where,

The predictor term \(\zeta ^p(t_{k+1})\), in the right side of equation (13) is evaluated by using Product rectangle rule as:

where,

Therefore, following equations represents the corrector formula for our diabetes model for \(0< \alpha \le 1\):

where the predictor terms are:

With the assistance of MATLAB software and the fractional Adams-Bashforth Moulton predictor-corrector algorithm, numerical simulations of system have been performed in this section to bolster the analytical findings of our model. The initial conditions used for simulation are \(S(0)= 97000, V(0)= 0, E(0)= 2549, I(0)= 451, T(0)=0\) and \(R(0)=0\). We solved the system for a various choice of \(\alpha\) values to explain the role of memory effect in the disease dynamics. Figure 8a represents the sharp decline in the susceptible population. This suggests that, over time, the model forecasts a decline in the susceptible population as individuals become exposed. Figure 8b shows the dynamics of vaccinated individuals. Through graph it is clear to see that initially the vaccinated population increase and stabilize over time with a gradual decline. Figure 8c and d illustrates the progression of the exposed and infected population respectively. The plot reveals a rapid initial peak and subsequently declines, with the curve eventually flattening over time. Figure 8e depict the dynamics of the population under treatment. It shows the consistent growth and the stabilization after 2015. Figure 8f represents the over time dynamics of recovered individuals which shows a constant increase that indicates the effectiveness of treatment. As \(\alpha\) decreases, solutions exhibit slower convergence and lower peaks, underscoring the role of memory in fractional-order models and their enhanced ability to reflect prolonged disease behavior compared to classical models.

Conclusion

This study introduces a mathematical model for TB transmission using the caputo fractional derivative for the better capture of disease dynamics. The analytical properties of the model such as non negativity, boundedness, uniqueness and existence are thoroughly investigated. Furthermore, using the next generation matrix approach, \(R_0\) is derived. Sensitivity analysis has been conducted to identify the key model parameters that exert the greatest influence on \(R_0\). The results suggest that decreasing transmissions and progression and by increasing the vaccine efficacy can significantly lower the TB transmission. For better visualization, 3D meshes and respective contour plots has been drawn. Validation of the model was done by using real data of Kenya from year 2000 to 2023. It reveals that the Caputo model provides a better fit to the real data for optimal fractional order 0.85 as indicated by a lower RMSE of approximately 0.02, compared to approximately 0.07 in the integer-order case. This result proves tha better alignment of fractional-order model with real TB data, highlighting its enhanced capability in representing the underlying disease dynamics accurately. With the use of Adams Bashforth Predictor Corrector method, numerical solutions of the model has been found. Behaviour of all model compartments across varying fractional order has been analyzed. Future work may explore the stochastic formulation or the fractal-fractional version of the current model to capture additional complexities in disease dynamics. Incorporating optimal control strategies is another promising direction to assess the effectiveness of intervention measures.

Data availability

The data used in this study is publicly available and has been obtained from the sources cited in the manuscript. Additionally, the data are available upon reasonable request from the first author, Bhamini Bhatia (bhaminibhatia56@gmail.com).

References

Castillo-Chavez, Carlos & Feng, Zhilan. To treat or not to treat: the case of tuberculosis. J. Math. Biol. 35, 629–656 (1997).

Shrestha, Sourya, Hill, Anil N., Marks, Suzanne M. & Dowdy, David W. Modeling the impact of tuberculosis vaccines on epidemiological and evolutionary outcomes. Sci. Transl. Med. 5(180), 180ra49 (2013).

Chauhan, Jignesh P., Khirsariya, Sagar R. & Hathiwala, Minakshi Biswas. A caputo-type fractional-order model for the transmission of chlamydia disease. Contemp. Math., 2134–2157 (2024).

Kumawat, Sangeeta, Bhatter, Sanjay, Bhatia, Bhamini, Purohit, Sunil Dutt & Suthar, D. L. Mathematical modeling of allelopathic stimulatory phytoplankton species using fractal-fractional derivatives. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 20019 (2024).

Jajarmi, Amin & Baleanu, Dumitru. A new fractional analysis on the interaction of hiv with cd4+ t-cells. Chaos Solitons Fractals 113, 221–229 (2018).

Bhatter, Sanjay, Bhatia, Bhamini, Kumawat, Sangeeta & Purohit, Sunil Dutt. Modeling and simulation of covid-19 disease dynamics via caputo-fabrizio fractional derivative. Comput. Methods Differ. Equ. 13(2), 494–504 (2025).

Diallo, Boubacar, Aguegboh, Nnaemeka Stanley, Osman, Shaibu, Dasumani, Munkaila & Okongo, Walter. Modelling rabies evolution with vaccination: A fractional calculus perspective. Sci. Afr., e03001 (2025).

Yeolekar, Mahesh A., Yeolekar, Bijal M., Khirsariya, Sagar R. & Chauhan, Jignesh P. Investigation of infertility treatments on infertile couples through fractional-order modeling approach. Int. J. Biomath. 2450155 (2025).

Ullah, Saeed, Baleanu, Dumitru, Khan, Abdul, Ahmad, Izaz & Rehman, Hafeez ur. Modeling and analysis of the transmission dynamics of tuberculosis: A fractional-order approach. Results Control Optim. 3, 100041 (2021).

Bhatter, Sanjay, Kumawat, Sangeeta, Purohit, Sunil Dutt & Suthar, D. L. Mathematical modeling of tuberculosis using caputo fractional derivative: A comparative analysis with real data. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 12672 (2025).

Purohit, Sunil Dutt, Baleanu, Dumitru & Jangid, Kamlesh. On the solutions for generalised multiorder fractional partial differential equations arising in physics. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 46(7), 8139–8147 (2023).

Aguegboh, Nnaemeka S., Phineas, Kiogora R., Felix, Mutua & Diallo, Boubacar. Modeling and control of hepatitis b virus transmission dynamics using fractional order differential equations. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci.2023(2023).

Yeolekar, Bijal M., Dave, Radhika D. & Khirsariya, Sagar R. Solution of a cancer treatment model of a drug targeting treatment through nanotechnology using adomian decomposition laplace transform method. Interactions 245(1), 278 (2024).

Naik, Parvaiz Ahmad, Yavuz, Mehmet, Qureshi, Sania, Jian, Zu. & Townley, Stuart. Modeling and analysis of COVID-19 epidemics with treatment in fractional derivatives using real data from Pakistan. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 135, 1–42 (2020).

Odibat, Zaid M. & Shawagfeh, Nabil T. Generalized Taylor’s formula. Appl. Math. Comput. 186(1), 286–293 (2007).

Ochieng, Francis Oketch. Mathematical modeling of tuberculosis transmission dynamics with reinfection and optimal control. Eng. Rep. 7(1), e13068 (2025).

Aguegboh, Nnaemeka Stanley, Nnaji, Daniel Ugochukwu, Okongo, Walter & Diallo, Boubacar. Modeling the dynamics of onchocerciasis using the atangana-baleanu fractional order with control measures. Sci. Afr., e03036 (2025).

Yang, Hyun Mo. The basic reproduction number obtained from jacobian and next generation matrices-a case study of dengue transmission modelling. Biosystems 126, 52–75 (2014).

Diallo, Boubacar et al. Fractional optimal control problem modeling bovine tuberculosis and rabies co-infection. Results Control Optim. 18, 100523 (2025).

Aguegboh, Nnaemeka Stanley et al. Existence and uniqueness of solution for a fractional hepatitis b model. Comput. Math. Biophys. 13(1), 20240009 (2025).

Chavada, Anil, Pathak, Nimisha & Khirsariya, Sagar R. A fractional mathematical model for assessing cancer risk due to smoking habits. Math. Model. Control 4(3), 246–259 (2024).

Khirsariya, Sagar R., Yeolekar, Mahesh A., Yeolekar, Bijal M. & Chauhan, Jignesh P. Fractional-order rat bite fever model: a mathematical investigation into the transmission dynamics. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 70(4), 3851–3878 (2024).

Hallauer Jr, William L., Slemp, Wesley C.H. & Kapania, Rakesh K. Matlab® curve-fitting for estimation of structural dynamic parameters, (2007).

World Bank. Incidence of tuberculosis (per 100,000 people)–kenya. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.TBS.INCD?locations=KE, (2024).

Nnaemeka, S., Ofe, Uko, Onyiaji, Netochukwu E., Lovelyn, Ugwu O. et al. Fractional model on the dynamics of chicken pox with vaccination. Int. J. Math. Trends Technol.-IJMTT, 67, (2021).

Acknowledgements

One of the authors (D.B.) would like to thank for the grant funding PIRF Project Number: I0074 provided by the Lebanese American University, Beirut, Lebanon.

Funding

The Authors received no funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B. and S.D.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Supervision. B.B.: Writing-Original draft preparation, Software. D.B. and D.L.: Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhatia, B., Bhatter, S., Purohit, S.D. et al. A fractional model based on caputo derivative for tuberculosis transmission using real data from Kenya. Sci Rep 16, 1725 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31440-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31440-0