Abstract

The hemodynamic characteristics of blood flow through a stenosed artery are analyzed in this study. A two-dimensional computational model is developed to simulate the behavior of a hybrid micropolar-Casson fluid flow with a magnetic field perpendicular to the flow, which mimics blood flow. The findings provide valuable insights into the complex dynamics of blood flow in narrowed arteries and help identify effective strategies for managing stenosis-related hemodynamic conditions. To optimize parametric values, a well-known technique called TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution) is employed. TOPSIS enabled a systematic evaluation and ranking of the alternatives of parametric values from best to worst based on their similarity to the ideal solution. The values from derived rankings are graphically represented and validated, demonstrating that the rankings are robust and consistent. It is evident from the results that the Hartmann Number can be used to control the flow separation region. The wall shear stress has a direct relation with the Hartman number and Casson parameter. The heat transfer rate for the hybrid nano fluid escalates with increasing values of Hartman number, Darcy parameter, and Strouhal number. The outcomes of this research have potential implications for cardiovascular health and can aid in developing advanced diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for stenotic arterial diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In fluid dynamics, the study of micropolar fluid theory has gained significant attention because of its ability to describe microstructural effects and micro-rotational motions of fluid particles that classical Newtonian models cannot capture. Casson fluid, on the other hand, is a non-Newtonian model characterized by yield stress and shear-thinning behavior, making it ideal for simulating biological fluids such as blood. The micropolar-Casson fluid model, which combines the properties of both micropolar and Casson fluids, provides an enhanced understanding of complex fluid behavior in systems involving non-Newtonian viscosity and microstructural dynamics. This model has broad applications, including polymer processing, drilling, and biomedical flow studies. Researchers such as Goud et al.1, Shamshuddin et al.2, Mehmood et al.3, and Ali et al.4 have contributed to this area by examining mixed convection, heat transfer, and pulsatile flow characteristics under various conditions. Vaidya et al.5 investigated the influence of homogeneous and heterogeneous chemical reactions on the peristaltic flow in narrowed arteries. They concluded that variable liquid properties enhance the velocity and temperature profiles. Prasad et al.6 conducted research on entropy generation and the influence of the magnetic field on Casson fluid flow in a non-uniform channel. Karmakar and Das7 proposed a neural network model to study bioelectromagnetics in blood circulation with tetra-hybrid nanoparticles and microbes. They reported that electroosmosis and nanoparticle geometry strongly affect flow and heat transfer characteristics. The model’s capacity to capture intricate physical mechanisms, such as microrotation and yield stress, makes it a powerful tool for understanding physiological and industrial fluid flow problems.

A constricted channel refers to a passage where the cross-sectional area decreases along its length, influencing flow patterns, pressure gradients, and wall shear stress. In physiology, this concept is particularly relevant to the study of blood flow in stenosed arteries, where narrowing due to plaque buildup can lead to significant changes in hemodynamics. Understanding fluid motion in such geometries is crucial for diagnosing and managing cardiovascular diseases. Studies by Abbas and Rafiq8 have explored the pulsatile and peristaltic flow of non-Newtonian micropolar-Casson fluids in constricted geometries, incorporating the effects of Lorentz forces, Darcy’s law, and thermal radiation. Beyond medical contexts, constricted channels also model airflow in the human respiratory system and fluid motion through porous media and microchannels. Research by Keshavarz Motamed et al.9 and Prastowo et al.10 demonstrates that constriction not only alters flow structure but also impacts mixing and deformation dynamics, emphasizing the role of geometry in controlling transport phenomena. Therefore, the study of micropolar-Casson fluid in constricted channels offers valuable insights into both physiological and engineering flow systems. More literature surveys can be seen in Upreti et al.11,12,13,14.

Hybrid nanofluids (HNFs) represent a recent advancement in heat transfer and energy transport technologies. By dispersing two or more types of nanoparticles in a base fluid, HNFs combine the superior thermophysical properties of different materials, leading to enhanced thermal conductivity, sability, and heat transfer efficiency compared to conventional nanofluids. The development of HNFs has enabled improvements in diverse applications such as solar energy harvesting, electronic cooling, heat exchangers, automotive engines, and biomedical systems. Studies by Sarkar et al.15 and Siddiqui et al.16 have explored the enhancement of heat transfer performance using hybrid nanofluids, demonstrating that their critical heat flux and cooling capacity can surpass those of traditional fluids. Similarly, Zeeshan et al.17 and Hassan et al.18 analyzed the impact of magnetic fields, rotation, and radiation on HNF behavior in porous media, showing notable improvements in thermal and material transport characteristics. Raza et al.19 investigated Casson nanofluid flow over a stretching sheet with slip and activation energy effects using RSM optimization. They found that magnetic and slip parameters strongly influence temperature and heat transfer rates. Li et al.20 studied peristaltic transport of Ree–Eyring fluid in a non-uniform compliant channel. They reported that wall properties and variable liquid properties significantly affect velocity, pressure rise, and temperature profiles. Mebarek-Oudina et al.21 investigated MgO–SWCNT/water hybrid nanofluid in a zigzag-walled cavity with obstacles. They showed that obstacle shape, Rayleigh number, and wall undulations significantly enhance heat transfer. Karmakar et al.22 modeled electro-osmotic blood circulation with trihybrid nanoparticles in an eccentric endoscopic arterial canal. They showed that electro-osmotic force and nanoparticle loading strongly influence flow and heat transfer. The potential of hybrid nanofluids to optimize flow and temperature regulation makes them especially relevant in biomedical contexts, such as improving blood-mimicking fluid models under complex flow conditions.

Karmakar and Das23 studied electro-osmotic blood flow with gold and alumina nanoparticles in a diverging fatty artery. They showed that electroosmosis boosts core flow but decreases near-wall streaming and heat transfer. Karmakar and Das24 modeled magnetized non-Newtonian blood with tri-nanoadditives in a charged artery. They concluded that electro-osmotic factors govern flow dynamics, while Joule heating and nanoparticle loading enhance thermal transport. Karmakar et al.25 analyzed EDL-driven blood transport with tetra-hybrid nanoparticles through a cilia-lined endoscopic artery. They found that nanoparticle geometry and cilia length significantly affect heat transfer and bolus formation. Karmakar and Das26 investigated electro-magnetized hybrid nano-blood circulation in a charged endoscopic artery. They showed that electro-osmosis, Lorentz force, and nanoparticle shape strongly influence hemodynamic and thermal responses. Das et al.27 modeled electrothermal blood flow with hybrid nanoparticles in a non-uniform endoscopic conduit. They reported that electroosmosis, Joule heating, and nanoparticle concentration significantly alter temperature, flow, and trapping phenomena. Das et al.28 simulated electro-magneto-hemodynamics of blood with bi-nanoparticles and clotting in an endoscopic canal. They showed that Hall and ion-slip effects, Joule heating, and nanoparticle loading strongly influence velocity, temperature, and bolus formation. Karmakar et al.29 used AI to predict electromagnetic blood flow with gold–maghemite nanoparticles under abrupt pressure gradients. They found that hybrid nano-blood enhances heat transfer, with AI achieving near-perfect accuracy in shear stress and heat transfer predictions. Karmakar et al.30 simulated neuro-computational blood flow with gold–maghemite nanoparticles in an electromagnetic microchannel. They found that hybrid nano-blood enhances heat transfer, with ANN giving highly accurate predictions. Karmakar and Das31 analyzed dynamic responses of a vibrating Riga sensor in a Pt-CeO₂-water hybrid nanofluid. They found electromagnetic forces strongly affect velocity and heat transfer, with ANN predictions showing near-perfect accuracy.

The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to the Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) is a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method used to evaluate and rank alternative solutions based on their distance from ideal and negative-ideal outcomes. By employing a systematic and data-driven approach, TOPSIS facilitates informed decision-making when multiple conflicting criteria are involved. In engineering and applied sciences, it has been successfully integrated with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and optimization frameworks to select optimal design or operating conditions. Abdollahi et al.32 applied a hybrid approach combining CFD, machine learning, and MCDM techniques for finned heat sink optimization, while Dwivedi and Sharma33 used TOPSIS with Shannon Entropy for selecting the best machining fluids. Bartwal et al.14 used the intuitionistic fuzzy set to analyze the flow and heat transfer analysis. In the present study, the TOPSIS method is applied to the numerical simulation of micropolar-Casson fluid flow in a constricted channel containing hybrid nanofluid. The coupling of fluid mechanics with a robust decision-making framework like TOPSIS offers a powerful approach for addressing complex multi-criteria challenges in modern fluid flow analysis.

The novelty of this study is as follows:

-

Generalization the ranking for the selection of different flow governing parameters. The values are ranked using the TOPSIS method to address MCDM challenges by utilizing a random hypergraph framework that illustrates the interrelationships among various criteria.

-

To analyze the impact of the magnetic field on blood flow in an artery with multiple stenosis,

-

A hybrid micropolar-Casson fluid with \(\:F{e}_{3}{O}_{4}\) Multi-wall Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNT) is considered for this study.

-

For identifying optimal parameter combinations that enhance heat transfer, minimize pressure loss, and improve overall system performance.

Problem formulation

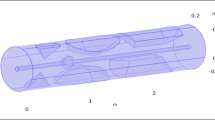

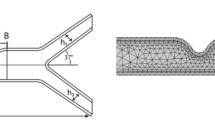

A two-dimensional multiple stenosed artery is examined to study the flow of a hybrid micropolar-Casson fluid, as illustrated in Fig. 1. To improve heat and mass transfer, two types of NFs are incorporated: Magnetite \(\:(Fe_{3}O_{4})\) nanoparticles and Magnetite-Multi-walled-carbon-nanotubes \(\:(Fe_{3}O_{4}-MWCNT)\) hybrid nanoparticles. The temperature and concentration at the lower \(\:\left({y}_{1}\right)\:\)and upper \(\:\left({y}_{2}\right)\) walls are denoted as \(\:{T}_{1},{C}_{1}\) and\(\:\:{T}_{2},{C}_{2}\:\), respectively.

Assumptions:

The following assumptions are considered for the current study:

-

Since blood has non-Newtonian characteristics, Casson fluid is used to mimic the blood flow due to its yield stress and shear-thinning behaviour. Micropolar fluid is used to incorporate the micro-rotational effect of suspended particles.

-

A magnetic field with strength \(\:{B}_{0}\) is applied perpendicular to the flow direction.

-

It is assumed that the magnetic Reynolds number \(\:{Re}_{m}\:(\:=UL\sigma\:{\mu\:}_{m}\:)\) is considerably small, i.e., \(\:{Re}_{m}\ll\:1\).

-

Reynolds number \(\:\left(Re=700\right)\) is fixed to ensure the laminar flow.

-

No slip conditions are applied on boundaries.

The non-Newtonian characteristics of the Casson fluid are defined by Ali et al.4:

where \(\:{\mu\:}_{\beta\:}\) is the fluid’s viscosity, \(\:{p}_{y}\) is pressure, \(\:\pi\:\) represents the deformation’s rate components product, \(\:{\pi\:}_{c}\) is the critical value of\(\:\:\pi\:\), and \(\:{e}_{ij}\) is the deformation rate’s \(\:{i}^{th}\) and \(\:{j}^{th}\) component respectively. The channel walls having stenosis are modelled using the following Ali et al.4

The flow governing equations are Ali et al.4:

We begin by identifying the variables and factors associated with the system under consideration. Let \(\:W\:\)be defined as \(\:H=\left(1+\frac{1}{\beta\:}\right)\left(\frac{k+{\mu\:}_{hnf}}{{\rho\:}_{hnf}}\right)\).The pressure is denoted by \(\:{p}^{*}\) while\(\:\:\:\rho\:\) represents the liquid density. The characteristic flow velocity, denoted by \(\:U\), corresponds to the average velocity at the inlet section over a specified time interval. The velocity components along the \(\:{x}^{*}\)-axis and \(\:{y}^{*}\)-axis are denoted by \(\:\overrightarrow{u}\) and \(\:\overrightarrow{v}\) respectively. The thermal field is indicated by \(\:{T}^{*}\) and the concentration by\(\:\:{C}^{*}\).

In the governing equations, the current density vector is denoted by \(\:J=\left({j}_{x},\:{j}_{y},\:{j}_{z}\right)\), while the magnetic field vector is given by \(\:B=\left({B}_{x},\:{B}_{y},\:{B}_{z}\right)=\left(0,\:{B}_{o},\:0\right)\). The electrical conductivity of the fluid is denoted by \(\:\sigma\:\), and \(\:{\mu\:}_{m}\) denotes the magnetic permeability of the medium. The micro-rotation velocity is denoted by \(\:{N}^{*}\), while the vortex viscosity is defined as \(\:k={L}^{2}\) is the vortex viscosity, and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{hnf}=\left({\mu\:}_{hnf}+\frac{k}{2}\right)j\) is spin gradient viscosity and \(\:j\) denotes the micro-inertia density. Owing to the presence of an electric current across the plane perpendicular to the main flow direction, Ohm’s law is applicable in describing the behavior of the electrical circuit.

The \(\:z-direction\) component of the electric field, denoted \(\:as\:{j}_{z}\) and oriented perpendicular to the flow plane, is accompanied by a uniform magnetic field strength represented as \(\:{B}_{0}\). Based on Maxwell’s equation for steady flow, \(\:\nabla\:\times\:E=0\), it can be concluded that the electric field \(\:{E}_{z}\) along the \(\:z-axis\) remains constant.

Now we compute

The non-dimensional measures are: \(\:x=\frac{{x}^{*}}{L}\),\(\:y=\frac{{y}^{*}}{L}\), \(\:u=\frac{\overrightarrow{u}}{U}\), \(\:v=\frac{\overrightarrow{v}}{U}\), \(\:t=\frac{{t}^{*}}{T}\), \(\:p=\frac{\overrightarrow{p}}{{\rho\:}_{f}{U}^{2}}\), \(\:Re=\frac{{\rho\:}_{f}UL}{{\mu\:}_{f}}\), \(\:St=\frac{L}{UT}\), \(\:M={B}_{o}L\sqrt{\frac{{\sigma\:}_{f}}{{\rho\:}_{f}{\upsilon\:}_{f}}}\), \(\:N=\frac{{N}^{*}L}{U}\), \(\:{D}_{a}=\frac{{\upsilon\:}_{f}}{U\sqrt{k}}\), \(\:K=\frac{k}{{\mu\:}_{f}}\), \(\:Sc=\frac{{\mu\:}_{f}}{{\rho\:}_{f}D},\) \(\:Rd=\frac{16\sigma\:{T}_{\infty\:}^{3}}{3{k}_{hnf}{\left(\rho\:{C}_{p}\right)}_{hnf}}\), \(\:\varphi\:=\frac{{C}^{*}-{C}_{2}}{{C}_{1}-{C}_{2}},\theta\:=\frac{{T}^{*}-{T}_{2}}{{T}_{1}-{T}_{2}},Sr=\frac{{\rho\:}_{f}D{K}_{T}{(T}_{1}-{T}_{2)}}{{\mu\:}_{f}{T}_{m}{(C}_{1}-{C}_{2})},\:Peh=Pr.Re,\:Pem=Sc.Re,\)

where \(\:M\:\)is the Hartman number, \(\:T\) is the flow oscillations period, \(\:St\) is the Strouhal number, \(\:K=\frac{k}{{\mu\:}_{f}}\) is the micropolar coefficient,\(\:\:Re\) is the Reynolds number, and D is the mass diffusivity coefficient. The effective thermophysical characteristics of HNF are listed in Table 1.

In subscripts, \(\:^{\prime}{f}^{\prime}\) and \(\:^{\prime}s^{\prime\:}\) represents the properties of the fluid and solid states, respectively, while \(\:\varphi\:\) indicates the volume fraction of the nanoparticles (NPs). The nano-sized materials examined in this paper include \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\:\)and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT). Table 2 lists the thermos-engineering features of water and nanoparticles employed in this research.

The non-dimensional form of Eqs. (4–11), after employing the transformation, is

Vorticity – Stream function formulation

The non-dimensional stream function \(\:\left(\psi\:\right)\) for 2D flow is defined as

By using the above transformations on equations \(\:\left(12\right)\), \(\:\left(13\right)\), and rearranging the results, we have:

The Poisson equation for the stream function \(\:\psi\:\) can be expressed as

Boundary conditions (BCs)

The initial and BCs for the variables are defined in the transformed coordinate system as follows:

The BCs for \(\:\omega\:\) in new coordinates are given as:

Similarly, BCs for \(\:\theta\:\) and \(\:{\varphi\:}\) in new coordinates are given as:

At the outlet, fully developed BCs are applied to all variables, with the flow exhibiting sinusoidal behavior characteristic of Womersley flow.

At the walls, conditions preventing slipping are taken into account:\(\:\:u=0\), \(\:v=0\). The BCs for micro-rotation velocity at the walls are

The factors \(\:S=1,\:S=0.5\), and \(\:S=0\) represent turbulent, weak, and strong flows of concentrated nanoparticles adjacent to the liquid walls, respectively. Furthermore, it is assumed that the inlet condition for the micro-rotation velocity is zero.

Coordinates transformation

A coordinate transformation is employed, which is defined as follows:

To transform the constricted part of the channel into a straight configuration, the lower boundary \(\:\left(y={y}_{1}\left(x\right)\right)\) and upper boundary \(\:\left(y={y}_{2}\left(x\right)\right)\) are mapped on \(\:\eta\:=0\) and \(\:\eta\:=1\), respectively.

After applying the coordinate transformation, the equations obtained are:,

This is the last coordinate transformation that must be used on the governing equations as they have been presented in a generalized, non-Cartesian, and non-orthogonal framework. To counteract this complexity, we convert the domain from a non-uniform and irregular geometry into one of straight and uniform boundaries. In this transformed coordinate system, the boundaries are flat and consistent, aligning with the original system only when the boundary itself is flat. This crucial step facilitates the application of numerical methods for solving the equations, which will be discussed in detail in the next section.

Numerical scheme and methodology

This section focuses on the numerical methods employed to address the system of equations derived in the preceding section. Following the coordinate transformation discussed in Sect. “Problem formulation”, we arrived at the system of Eqs. (21)-(25). We use the domain for \(\:\xi\:,\eta\:\) to be\(\:\:\xi\:\in\:[-10\:10]\) and \(\:\eta\:\in\:[-10\:10]\). For the numerical resolution, we considered a Cartesian grid of \(\:400\:\times\:51\) elements. Moreover, we use the time step size \(\:{\Delta\:}t={10}^{-4}\) for flow oscillations. At the time level \(\:l\) the resolution is already known, but for \(\:l=\text{0,1},2,\cdots\:\), we will compute at the level of time \(\:l+1\). Equation (27) is numerically computed for \(\:\psi\:=\psi\:(\xi\:,\:\eta\:)\). Employing the Tri-Diagonal Matrix Algorithm (TDMA) alongside Central Differences (CD) to compute the spatial derivatives for discretization, the Alternative Direction Implicit Scheme is applied to solve equations (21) to (26) for the respective variables \(\:\omega\:=\omega\:\left(\xi\:,\eta\:\right),\:\theta\:=\theta\:\left(\xi\:,\eta\:\right),\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{\varphi\:}={\varphi\:}\left(\xi\:,\eta\:\right)\) respectively. By leveraging fundamental differences, we can discretize spatial derivatives, while forward and backward differences are employed for time derivatives. To expedite results, parallel computing may be utilized.

TOPSIS method

TOPSIS is a method for MCDM that evaluates alternatives based on their closeness to an optimal solution and their distance from a negative optimal solution. It is appreciated for its simplicity and effectiveness in addressing both quantitative and qualitative criteria. Let us have \(\:m\) alternatives \(\:\left({Alt}_{1},\:{Alt}_{2},\:\:{Alt}_{3}\dots\:{Alt}_{m}\right)\), every alternative \(\:{Alt}_{i}\)has \(\:n\) criteria \(\:({q}_{1},\:{q}_{2},\:{q}_{3}\:.\:.\:.\:{q}_{n})\), expressed by positive numbers \(\:{(q}_{ij})\) as shown in Table 3.

The procedure for the TOPSIS method is outlined as follows:

Decision matrix (DM)

Let us consider a DM.

DM in normalized form

To reduce discrepancies in scale across criteria, convert the raw data in the DM into dimensionless values.

Thus, DM \(\:\left(A\right)\) after normalization becomes,

Decision matrix in weighted normalized form

Assign weights to each criterion to reflect its significance in the decision-making process. Then, multiply the normalized values in DM by their respective weights.

The Weighted Matrix after normalization becomes \(\:{x}_{ij}={w}_{j}*{N}_{ij}\),

Optimal best/optimal worst

In this step, we identify the most favorable (ideal solution) and least favorable (worst solution) values for each criterion by using the following formulas.

where \(\:I\) denotes the column of favorable criteria and \(\:J\) denotes the column of unfavorable criteria.

Euclidean distance from optimal Best/Optimal worst

\(\:{D}^{+}\) is the Euclidean distance from the IB, computed by the following formula

\(\:{D}^{-}\) which is the Euclidean distance from the IW resolution, computed by the following formula

Performance score

At this step, the performance \(\:\left(P\right)\) is computed as,

Ranking alternatives

In the final step, the alternatives (Pi) are ranked, and the highest value represents the ideal solution.

Discretization

The final coordinate transformation-derived equations will be discretized in a manner akin to that used by Ali. et al.36. The continuous issue can be discretized into a set of discrete equations using this approach, which makes it possible to solve them numerically. This systematic and consistent technique ensures uniform treatment of the governing equations, leading to accurate and reliable numerical solutions. To validate the current study, Fig. 2 compares the current study with Ali. et al.36. The comparison shows a strong agreement. We will examine the outcomes of these numerical solutions in the next section, showing how different flow-regulating factors affect the profiles of concentration, velocity, micro rotation temperature, and WSS (WSS).

Comparison of wall shear stress on the upper wall with Ali. et al.36.

Results and discussion

This section examines how the flow-controlling premerger affects WSS, velocity, micro rotation velocity, thermal, and concentration profiles when \(\:M\),\(\:\:St\),\(\:\:\beta\:\), \(\:{D}_{a}\), \(\:Re\), \(\:Rd\), \(\:Peh\), \(\:Pem\), \(\:Sr\), \(\:{\varphi\:}_{1}\), and \(\:{\varphi\:}_{2}\:\)by varying one factor at a time and keeping others as constraints. All the parameters are held constant at the baseline values to isolate the effect of other parameters. The parameters are fixed as: \(\:M=10,\:St=0.003,\beta\:=0.4,\:{D}_{a}=0.002,\:Re=700,\:Rd=0.7,\:Peh=310,\:Pem=370,\:Sr=1.1,\:{\varphi\:}_{1}=0.002,\:{\varphi\:}_{2}=0.003.\) We will also examine the outcomes achieved through the successful implementation of the TOPSIS Algorithm and its impact on heat transfer rates.

Impact of different flow governing factors on WSS, \(\:\varvec{u}\), \(\:\varvec{\theta\:}\), \(\:\varvec{N}\) and \(\:\varvec{\varphi\:}\) profiles

Magnetic factor \(\:\varvec{M}\)

Figure 3 depicts the impact of NF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) and HNF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\)-MWCNT on (a) WSS, (b) \(\:u-\)profile at x = 5 and (c) \(\:N-\)profile at \(\:x=0\), (d) and \(\:\theta\:-\)profile at \(\:x=-5\) for the Hartman number \(\:M=0,\:10,\:20\). Figure 3(a) shows that as the magnetic factor \(\:M\) increases, the WSS also rises, peaking at \(\:t=0.25\). It is because the Lorentz force near the wall is maximum, and to maintain the overall flow rate, the fluid near the wall moves faster, creating a steeper velocity gradient at the wall. The WSS for the NF exceeds that of the HNF. Figure 3(b) indicates that the boundary layer thickness expands with the escalation of \(\:\:M\). As the value of \(\:M\)escalates, the resistance forces increase while the velocity field diminishes. At \(\:x=5\), the velocity profile of the HNF is greater than that of the NF. Figure 3(c) reveals that the micro-motion velocity profile declines as \(\:M\) increases, with the HNF exhibiting slightly more pronounced effects than the NF. The momentum and thermal properties sustain slightly higher velocity downstream despite the Lorentz force. Figure 3(d-e) illustrates that the Hartmann number is inversely related to the microrotation velocity. Since the magnetic field damps the microrotation of the microelements, it leads to a reduction in microrotation energy.

Reynolds number \(\:\varvec{R}\varvec{e}\)

Figure 4 presents the effect of NF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) and HNF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\)-MWCNT on (a) WSS, (b) \(\:u\) at \(\:x=2\), and (c) \(\:N\) at \(\:x=0\) for the Reynolds numbers \(\:Re=500,\:900,\:1300\). Figure 4(a) illustrates that the WSS increases as Re increases, reaching its peak value at \(\:t=0.25\). As the inertial forces dominate when \(\:Re\) escalates, resulting in a steeper velocity gradient at the wall, causing a hike in WSS. The WSS of the NF exceeds that of the HNF because of higher viscosity near the wall than HNF. Figure 4(b) presents that the velocity profile of NF is lower compared to that of the HNF. Since the HNF has lower internal resistance, the velocity profile of the HNF achieves higher values as compared to the NF. The flow profiles are non-oscillatory due to the significant backward flow observed at the walls at \(\:x=2\). Figure 4(c) indicates that an increase in the Reynolds number \(\:\left(Re\right)\) enhances the effects on the \(\:N\) profiles, with NF exhibiting slightly greater effects than HNF. This may be attributed to the shear-thinning characteristics of the HNF, where effective viscosity approaches a constant value at high shear rates. It is important to note that any shear-thinning fluid behaves similarly to a Newtonian fluid at higher Re values.

Casson liquid factor \(\:\varvec{\beta\:}\)

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of NF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) and HNF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}-MWCNT\) on various factors: (a) WSS, (b) u at \(\:x=0\), (c) \(\:N\) at \(\:x=0\), (d) \(\:\theta\:\) at \(\:x=-5,\) considering the Casson fluid parameter \(\:\beta\:\) values of \(\:0.4,\:0.8,\:and\:1.2\). In Fig. 5(a), it is reflected that escalation in \(\:\beta\:\) values leads to a rise in the WSS, peaking at\(\:\:t=0.25\). The higher values of \(\:\beta\:\), showcase the Newtonian fluid behavior, leading to low shear stress resulting in a higher velocity gradient, which increases the WSS. The shear stress for the NF surpasses that of the HNF because of the higher viscosity of the HNF as compared to the NF. Additionally, the boundary layer thickness for velocity diminishes with increasing\(\:\:\beta\:\). Figure 5(b) indicates that the velocity profile of the HNF is lower than that of the NF at \(\:x=0\) and\(\:\:2\). Figure 5(c) reveals that higher \(\:\beta\:\) values result in reduced effects on \(\:N\) profile, with the NF exhibiting slightly greater effects than the hybrid variant. With the higher values of \(\:\beta\:\), there a less internal resistance to particles, leading to lower microrotation velocity. Figure 5(d) demonstrates that as \(\:\beta\:\) increases, the \(\:\theta\:-\)profile decreases, with the HNF showing a higher temperature profile compared to the NF. Since the MCNTs are excellent thermal conductors, adding them with \(\:F{e}_{3}{O}_{4}\) enhances the thermal conductivity of the HNF than NF.

Vortex viscosity factor \(\:\varvec{K}\)

Figure 6 illustrates the impact of NF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) and HNF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}-MWCNT\) on various factors: (a) WSS, (b) \(\:u-\)profile at \(\:x=2\), (c) \(\:N-\)profile at \(\:x=0\), and (d) \(\:\theta\:\) profile at \(\:x=-5\), for vortex viscosity factors \(\:K=0.3,\:0.7,\) and \(\:1.1.\) In Fig. 6(a), it is shown that the uprising in the values of \(\:K\) causes the rise in the WSS profile. A higher vortex viscosity escalates the fluid’s internal resistance to spin, which results in a higher effective viscosity and thus higher WSS. Figure 6(b) indicates that the velocity profile of the NF is considerably lower than that of the HNF. Escalating the vortex viscosity dissipates the energy in order to overcome the internal spin resistance, slowing down the fluid velocity. The profiles do not exhibit oscillations due to notable backflow near the walls at \(\:x=2\), resulting in a higher velocity profile for the HNF. Figure 6(c) reveals that increasing the \(\:K\) factor positively influences \(\:N\) profiles, with the HNF demonstrating slightly greater effects than the NF. Higher values of \(\:K\) allow the stronger gradient of particle spin, leading to a higher microrotation velocity profile. Figures 6(d) indicates that as \(\:K\) increases, \(\:\theta\:-\)profile decreases, with the HNF showing marginally higher \(\:\theta\:-\)profile compared to the NF.

Other factors \(\:\varvec{P}\varvec{e}\varvec{h},\:\varvec{P}\varvec{e}\varvec{m}\), and \(\:\varvec{S}\varvec{r}\)

Figure 7 shows the effects of NF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) and HNF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\)-MWCNT on (a) the temperature profile at \(\:x=2\) and (b) at \(\:x=-5\) for the heat diffusion factor \(\:Peh=350,\:840,\:1050\). As the \(\:Peh\) value becomes more precise, the temperature profile falls. Increasing the Peh value, advection dominates over conduction, flattening the thermal boundary layer and causing a decline in the temperature profile. The HNF temperature profile is marginally better than the NF for temperature profiles because MWCNTs are exceptional heat conductors.

Figure 8 illustrates the impact of NF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) and HNF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}-MWCNT\) on the \(\:\varphi\:-\)profile (a) at \(\:x=0\) and (b) at \(\:x=2\) for the mass diffusion parameter \(\:Pem=280,\:630,\:and\:910.\) The figure indicates that the concentration profile diminishes as the \(\:Pem\) value increases. Escalating the Pem values, advection dominates over diffusion, resulting in a thinner concentration boundary layer, and a declining trend is observed in the concentration profile. In comparison to the HNF, the concentration profile of the NF is relatively lower.

Figure 9 illustrates the impact of NF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) and HNF \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}-MWCNT\) on (a) the concentration profile at \(\:x=-5\) and (b) the concentration profile at \(\:x=0\) for Soret numbers \(\:Sr=0.8,\:1.1,\:and\:2.\) The figure indicates that the concentration profile increases as the Soret number escalates. Notably, the concentration profile of the NF is more pronounced than that of the HNF.

Influence of additional engineering factors: Sherwood number \(\:\left(\varvec{S}\varvec{h}\right)\), skin friction coefficient \(\:\left(\varvec{S}\varvec{k}\right)\), Nusselt number \(\:\left(\varvec{N}\varvec{u}\right)\)

Fig. 10 illustrates how numerous flow governing factors affect the Nusselt number \(\:\left(Nu\right).\) The Nusselt number increases with stronger values of \(\:M\), \(\:Da\), and \(\:St\), while it decreases with higher values of \(\:\beta\:\), \(\:Rd\), and \(\:Re\). Increasing the magnetic field parameter results in an escalating temperature gradient and enhances conductive heat transfer rate, thereby increasing the Nusselt number. The escalating values of the Radiation parameter lead to a lower conductive heat transfer rate, resulting in a decreasing Nusselt number.

Fig. 11 shows the effect of different factors on the Sherwood number \(\:Sh\). It is observed that \(\:Sh\) increases as the values of \(\:M\), \(\:\beta\:\), \(\:Da\), \(\:St\), \(\:Rd\), and \(\:Pem\) escalate; on the other hand, \(\:Sh\) decreases as increasing values of \(\:Re,\) \(\:K\) and \(\:Sr\). Higher values of Pem mean the domination of advection which results in the concentration gradient and boosts the Sherwood number. Escalating values of \(\:Re\) lead to a thicker concentration boundary layer, reducing the efficiency of nanoparticle transport from the wall, resulting in a lower Sherwood number.

Fig. 12 shows how various flow factors influence the skin friction coefficient, \(\:Sk\). \(\:Sk\) is directly linked to \(\:\beta\:\), \(\:Da\), \(\:St\), \(\:Re\), and \(\:\varphi\:\), while it has an inverse relationship with \(\:M\) and \(\:K\). Escalated values of \(\:Re\) lead to a thinner velocity boundary layer and a steeper velocity gradient, resulting in an escalation of the skin friction coefficient.

TOPSIS results

To begin with, the Decision Matrix is established in Table 4 as illustrated in Sect. “Decision matrix (DM)”. Afterward, we apply normalization to the values using the formula given in Sect. “DM in normalized form”, outlined in Table 5. This is followed by adjusting the DM by dividing each element in every column by its respective normal value, discussed in Sect. “Decision matrix in weighted normalized form”, shown in Table 6. Finally, the weighted normalized matrix is formed by multiplying these values by the weights, as illustrated in Sect. “Euclidean distance from optimal best/optimal worst”, constructed in Table 7. In the following step, the ideal best \(\:(I+)\) and ideal worst \(\:(I-)\) values for each attribute are calculated. The Euclidean distances \(\:(D+)\) and \(\:(D-)\) are then computed. Afterward, performance scores \(\:\left(P\right)\) are established. Finally, once all results are gathered, the alternatives are ranked to identify the optimal set of choices, as detailed in Table 8. The alternative with the utmost P value is selected as the preferred option. The alternatives \(\:{A}_{21}\) with values \(\:M=7.3\times\:{10}^{-2},\:St=6.2\times\:{10}^{-2},\)\(\:Re=-1.0\times\:{10}^{-2},\:Da=9.0\times\:{10}^{-3},\:K=-9.0\times\:{10}^{-3},\)\(\:Rd=-8.0\times\:{10}^{-3},\:Peh=7.0\times\:{10}^{-3},\:Pem=9.0\times\:{10}^{-3},\)\(\:Sr=4.0\times\:{10}^{-3},\:\beta\:=-1.5\times\:{10}^{-2}\) and \(\:\varphi\:=8.0\times\:{10}^{-3}\) has utmost value \(\:8.533\times\:{10}^{-1}\). The ranking of the alternatives is also given in Table 8.

Result verification for TOPSIS

Figure 13 demonstrates the top three ranked values as shown in Table 8. A distinct performance hierarchy is revealed in the comparative analysis of top three ranked values for heat transfer rate. The optimum value of Nusselt number is obtained from those parametric values ranked 1 st by the TOPSIS. Further the second and third ranked parametric values show the declining trend as compared to first. Additionally, the plots facilitated a comparison of Nusselt number for nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid: \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}\) NF and \(\:Fe_{3}O_{4}-MWCNT\) HNF.

Conclusions

This study presents the flow characteristics of a viscous, incompressible magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) micropolar-Casson fluid through a constricted channel. The impact of different flow governing factors, including magnetic parameter \(\:\left(M\right)\), Casson parameter \(\:\left(\beta\:\right)\), Reynolds number \(\:\left(Re\right)\), porosity parameter \(\:\left(Da\right)\), radiation parameter \(\:\left(Rd\right)\), vortex viscosity \(\:\left(K\right)\), Soret number \(\:\left(Sr\right)\), Solid Volume Fraction \(\:\left(\varphi\:\right)\), Peclet number for Heat and Mass Diffusion parameter \(\:(Peh\:\&\:Pem\)) on the WSS, velocity \(\:\left(u\right)\), thermal \(\:\left(\theta\:\right)\), and concentration (\(\:\varphi\:)\) profiles to compare the behavior of \(\:{Fe}_{3}{O}_{4}\)-based NF and \(\:{Fe}_{3}{O}_{4}\)-MWCNT-based HNF, are graphically presented. The TOPSIS approach is used to find parametric values to enhance the heat transfer rate. The study’s important points are listed below:

-

The WSS escalates with the increasing value of \(\:M\), \(\:St\), \(\:\beta\:\), and deescalates by increasing the value of \(\:K\), \(\:Da,\:Re\), \(\:Da\), and \(\:\varphi\:\).

-

The Hartmann number can be used as a parameter to control flow separation region.

-

The micro-rotation velocity profiles show decreasing behavior by increasing the values of \(\:M\), \(\:\beta\:\) and an increasing trend while the values of \(\:St\), \(\:Re\), \(\:Da\), \(\:K\) increases. The NF shows more effects on micro-rotation velocity as compared to HNF.

-

As the factors \(\:M,\:St,\:\beta\:,\) and \(\:Re\) increase, the thickness of the boundary layer for the velocity field also increases. Conversely, the thickness decreases with higher values of \(\:Re,\:Da,\:K,\:\)and \(\:\varphi\:\), while the velocity field diminishes, except for \(\:\beta\:\), which exhibits the opposite behavior. The restricting force intensifies with an increase in the Hartmann number, leading to a decrease in the velocity field.

-

Temperature profiles increase as \(\:M\), K, \(\:Da\), \(\:Re\), \(\:Rd\), and \(\:\varphi\:\) escalates while decreases as the \(\:\beta\:\),\(\:\:St\), and \(\:Peh\) values increase.

-

When comparing NF and HNF, HNF causes a quick increase in temperature because it improves thermal conductivity. As a result, it is inferred that the HNF experiences higher temperatures than the NF.

-

Nusselt Number grows on \(\:M\), \(\:Da\), and the Sherwood number increases on \(\:M\), \(\:\beta\:\), \(\:St\), \(\:Rd\), and \(\:Pem\), and the Skin friction Coefficient increases on \(\:M\), \(\:\beta\), and \(\:Da\) as the values increase. \(\:Nu\) decreases by escalating \(Rd\) and \(\:Sh\) has a declining trend on increasing \(\:Sr\) and \(\:Sk\) declines for \(\:M\) and \(\:K\) as they increase.

Overall, the study provided insights into the circulatory system’s heat and mass transfer activity, specifically related to the blood supply and potential applications in hyperthermia therapies. The findings shed light on the behavior and characteristics of the NF and HNF in the context of the analyzed flow scenario, aiding in understanding their performance and potential benefits in drug delivery.

Limitations and future work

The analysis is confined to a two-dimensional domain, which neglects the significant three-dimensional flow behaviors potentially leading to underestimation of flow behavior. This model also assumes a uniform and unidirectional magnetic field, which in realistic scenarios could be non-uniform. The TOPSIS method, although robust, is sensitive to the subjective weighting criteria. This work can be extended to develop a 3D computational model that can capture complex phenomena. The current micropolar-Casson fluid model can be expanded to include more complex rheological behaviors, e.g. viscoelasticity.

Data availability

All the data used is presented in the paper.

Abbreviations

- y₁, y₂:

-

Lower/upper wall positions (m)

- h₁, h₂:

-

Constriction heights (m)

- u*, v*:

-

Velocities in x*, y* directions (m/s)

- p*:

-

Pressure (Pa)

- \(\uprho\) :

-

Density (kg/m³)

- \(\upmu\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity (Pa·s)

- \(\upmu\upbeta\) :

-

Plastic dynamic viscosity (Pa·s)

- \(\upmu\)mf :

-

Effective dynamic viscosity (Pa·s)

- K:

-

Vortex viscosity (Pa·s)

- \(\upnu\) :

-

Kinematic viscosity (m²/s)

- \(\upsigma\) :

-

Electrical conductivity (S/m)

- cp:

-

Specific heat capacity (J/(kg·K))

- D:

-

Mass diffusivity (m²/s)

- j:

-

Micro-inertia density (kg·m²)

- \(\upphi\) :

-

Solid volume fraction (Dimensionless)

- \(\upbeta\) :

-

Casson parameter (Dimensionless)

- K:

-

Micropolar parameter (Dimensionless)

- M:

-

Hartmann number (Dimensionless)

- Re:

-

Reynolds number (Dimensionless)

- Da:

-

Darcy number (Dimensionless)

- Sc:

-

Schmidt number (Dimensionless)

- St:

-

Strouhal number (Dimensionless)

- Nu:

-

Nusselt number (Dimensionless)

- Sh:

-

Sherwood number (Dimensionless)

- \(\uppi\) :

-

Deformation rate product (Pa·s)

- N:

-

Micro-rotation velocity (s⁻¹)

- \(\gamma\) :

-

Spin gradient velocity (m²/s)

- \(\uppsi\) :

-

Stream function (m²/s)

- \(\upomega\) :

-

Vorticity (s⁻¹)

References

Goud, B. S., Reddy, Y. D. & Asogwa, K. K. Chemical reaction, Soret and dufour impacts on magnetohydrodynamic heat transfer Casson liquid over an exponentially permeable stretching surface with slip effects. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 37 (13), 2350124 (2023).

Shamshuddin, M. D., Asogwa, K. K. & Ferdows, M. J. N. H. T. Thermo-solutal migrating heat producing and radiative Casson NF flow via bidirectional stretching surface in the presence of bilateral reactions. Numer. Heat. Transf. Part. A: Appl. 85 (5), 719–738 (2024a).

Mehmood, Z., Mehmood, R. & Iqbal, Z. Numerical investigation of micropolar Casson liquid over a stretching sheet with internal heating. Commun. Theor. Phys. 67 (4), 443 (2017).

Ali, A., Umar, M., Bukhari, Z. & Abbas, Z. Pulsating flow of a micropolar-Casson liquid through a constricted channel influenced by a magnetic field and Darcian porous medium: A numerical study. Results Phys. 19, 103544 (2020).

Vaidya, H. et al. Combined effects of homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions on peristalsis of Ree-Eyring liquid: application in hemodynamic flow. Heat. Transf. 50, 2592–2609. https://doi.org/10.1002/htj.21995 (2021).

Prasad, K. V. et al. Peristaltic activity in blood flow of Casson nanoliquid with irreversibility aspects in vertical non-uniform channel. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 99 (8), 100617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jics.2022.100617 (2022).

Karmakar, P. & Das, S. A neural network approach to explore bioelectromagnetics aspects of blood circulation conveying tetra-hybrid nanoparticles and microbes in a ciliary artery with an endoscopy span. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2024.108298 (2024a).

Abbas, Z. & Rafiq, M. Y. Numerical simulation of thermal transportation with viscous dissipation for a peristaltic mechanism of micropolar-Casson liquid. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47 (7), 8709–8720 (2022).

Keshavarz Motamed, P., Abouali, H., Poudineh, M. & Maftoon, N. Experimental measurement and numerical modeling of deformation behavior of breast cancer cells passing through constricted microliquidic channels. Microsystems Nanoengineering. 10 (1), 7 (2024).

Prastowo, T., Fahmi, M. N. & Realita, A. Transport of water masses through a constricted channel with a sill: possible application to Indonesian through-Flow. Ocean. Sci. J. 59 (4), 52 (2024).

Upreti, H., Pandey, A. K., Kumar, M. & Makinde, O. D. Darcy–Forchheimer flow of CNTs-H₂O nanofluid over a porous stretchable surface with Xue model. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. *37* (28), 2350243. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217979223502435 (2023).

Upreti, H., Mishra, S. R., Pandey, A. K. & Pattnaik, P. K. Thermodynamics analysis of Casson hybrid nanofluid flow over a porous Riga plate with slip effect. Int. J. Multiscale Comput. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1615/IntJMultCompEng.2024051153 (2024).

Upreti, H., Pandey, A. K., Lingwal, S. & Bartwal, P. Free convective flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid around a horizontal circular cylinder with thermal radiation using differential transformation method. Multidiscipline Model. Mater. Struct. https://doi.org/10.1108/MMMS-02-2025-0050 (2025).

Bartwal, P., Joshi, B. P., Upreti, H., Pandey, A. K. & Tripathi, D. 20 Magnetohydrodynamics stagnation point flow of tangent hyperbolic fluid over a non-flat rotating disk in intuitionistic fuzzy environment. Journal Ocean. Eng. Science (2025).

Sarkar, J., Ghosh, P. & Adil, A. A review on HNF: recent research, development and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 43, 164–177 (2015).

Siddiqui, F. R., Tso, C. Y., Qiu, H., Chao, C. Y. & Fu, S. C. HNF spray cooling performance and its residue surface effects: toward thermal management of high heat flux devices. Appl. Therm. Eng. 211, 118454 (2022).

Zeeshan, A., Ellahi, R., Rafique, M. A., Sait, S. M. & Shehzad, N. Parametric optimization of entropy generation in HNF in contracting/expanding channel by means of analysis of variance and response surface methodology. Inventions 9 (5), 92 (2024).

Hassan, A. et al. Heat transport investigation of HNF (Ag-CuO) porous medium flow: under magnetic field and Rosseland radiation. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13 (5), 101667 (2022).

Raza, J., Mebarek-Oudina, F., Ali, H. & Sarris, I. E. Slip effects on Casson nanofluid over a stretching sheet with activation energy: RSM analysis. Front. Heat. Mass. Transf. 22 (4), 1017–1041. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2024.052749 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Peristaltic transport of a Ree‐Eyring fluid with non‐uniform complaint channel: an analysis through varying conditions. ZAMM ‐ J. Appl. Math. Mech. / Z. Für Angewandte Math. Und Mechanik. 104 (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/zamm.202300073 (2023).

Mebarek-Oudina, F. et al. Thermal performance of MgO-SWCNT/water hybrid nanofluids in a zigzag walled cavity with differently shaped Obstacles. Mod. Phys. Lett. B. https://doi.org/10.1142/s0217984925501635 (2025).

Karmakar, P., Ali, A. & Das, S. Circulation of blood loaded with trihybrid nanoparticles via electro-osmotic pumping in an eccentric endoscopic arterial Canal. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 141, 106593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106593 (2022b).

Karmakar, P., Barman, A. & Das, S. EDL transport of blood-infusing tetra-hybrid nano-additives through a cilia-layered endoscopic arterial path. Mater. Today Commun. 36, 106772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106772 (2023a).

Karmakar, P. & Das, S. Modeling non-Newtonian magnetized blood circulation with tri-nanoadditives in a charged artery. J. Comput. Sci. 70, 102031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2023.102031 (2023b).

Karmakar, P. & Das, S. Electro-Blood circulation fusing gold and alumina nanoparticles in a diverging fatty artery. BioNanoScience 13 (2), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12668-023-01098-x (2023a).

Karmakar, P. & Das, S. EDL induced electro-magnetized modified hybrid nano-blood circulation in an endoscopic fatty charged arterial indented tract. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 15 (2), 171–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13239-023-00705-y (2023c).

Das, S., Karmakar, P. & Ali, A. Electrothermal blood streaming conveying hybridized nanoparticles in a non-uniform endoscopic conduit. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 60 (11), 3125–3151 (2022).

Das, S., Karmakar, P. & Ali, A. Simulation for bloodstream conveying bi-nanoparticles in an endoscopic Canal with blood clot under intense electromagnetic force. Waves Random Complex. Media. 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/17455030.2023.2198036 (2023).

Karmakar, P., Das, S. & Das, S. AI-based prediction of flow dynamics of blood blended with gold and maghemite nanoparticles in an electromagnetic microchannel under abruptly changes in pressure gradient. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15368378.2025.2501733 (2025).

Karmakar, P., Das, S., Das, S. & Das, S. Neuro-computational simulation of blood flow loaded with gold and maghemite nanoparticles inside an electromagnetic microchannel under rapid and unexpected change in pressure gradient. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/15368378.2025.2453923 (2025).

Karmakar, P. & Das, S. AI-powered computational analysis of dynamic responses in a vibrating Riga sensor within a reactive platinum -cerium oxide-water mixture. Sens. Actuators Phys. 381, 116028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2024.116028 (2024b).

Abdollahi, S. A. et al. A novel insight into the design of perforated-finned heat sinks based on a hybrid procedure: computational liquid dynamics, machine learning, multi-objective optimization, and multi-criteria decision-making. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 155, 107535 (2024).

Dwivedi, P. P. & Sharma, D. K. A study for an optimization of cutting liquids in machining operations by TOPSIS and Shannon entropy methods. WSEAS Trans. Liquid Mech. 19, 83–98 (2024).

Ali, A., Bukhari, Z., Umar, M. & Abbas, Z. Cu and Cu-SWCNT nanoparticles’ suspension in pulsatile Casson fluid flow via Darcy–Forchheimer porous channel with compliant walls: A prospective model for blood flow in stenosed arteries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (12), 6494. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22126494 (2021).

Swain, K., Mebarek-Oudina, F. & Abo-Dahab, S. M. Influence of MWCNT/Fe3O4 hybrid nanoparticles on an exponentially porous shrinking sheet with chemical reaction and slip boundary conditions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 143 (2), 1155–1163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-020-10432-4 (2021).

Ali, A., Fatima, A., Bukhari, Z., Farooq, H. & Abbas, Z. Numerical investigation of thermally developed MHD flow with pulsation in a channel with multiple constrictions. AIP Adv. 11 (5), 055320. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0052276 (2021a).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have equal contributions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Umar, M., Zeeshan, M., Rafiq, S. et al. Numerical simulations of blood flow in a stenosed artery using a multi-criteria decision-making Algorithm. Sci Rep 16, 4527 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31493-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31493-1