Abstract

The accurate and non-invasive detection of bilirubin in urine is crucial for medical diagnostics. Traditional methods often face challenges such as invasiveness, complexity, and the requirement for specialized equipment. In this study, we propose a tunable plasmonic metamaterial sensor enhanced with nanocrystals for terahertz (THz) wave engineering, enabling direct, non-invasive estimation of bilirubin concentrations in urine. Computational electromagnetic simulations reveal an operating wavelength of 952 nm, a sensitivity (SS) of 325 nm/RIU, a figure of merit (FoM) of 65, a quality factor (Q) of 366.75, and an electric field intensity enhancement (EFIE) of 1714. These results demonstrate the sensor’s high performance and indicate its optimal efficiency point. Compared with conventional approaches, the proposed device provides higher detection sensitivity and sharper resonance, highlighting its potential as an efficient and non-invasive tool for bilirubin monitoring in urine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urine bilirubin levels can indicate various diseases and conditions. Accurately and non-invasively detecting urine bilirubin levels presents challenges across different methods1. Traditional approaches for measuring bilirubin levels often involve invasive procedures such as blood sampling through needle insertion. These methods can be uncomfortable for patients and involve some complexity2. The complexity of analyzing bilirubin levels with standard laboratory techniques necessitates specialized equipment and trained personnel3. These methods typically involve chemical analysis or spectrophotometric measurements, which may not be easily accessible in all healthcare settings4.

Conventional THz biosensing techniques for biological fluids still face limitations in sensitivity, resonance tunability, and field confinement, which restrict their practical application in non-invasive diagnostics5. To address these challenges, recent studies have explored advanced metamaterial and graphene assisted THz platforms that offer stronger electromagnetic confinement, enhanced selectivity, and improved miniaturization potential. For instance, Rafighirani et al. demonstrated graphene-based metasurfaces with remarkable sensitivity improvements and polarization-independent behavior, highlighting the promise of graphene-enabled THz absorbers for high-performance biochemical sensing6,7. Similarly, Wang et al. reported multifunctional metasurfaces and tunable resonance architectures, showing the potential of metamaterial systems for broadband and multi-analyte detection8. In another study, they provided a comprehensive review discussing the key challenges and opportunities in realizing high-performance THz biosensors, particularly regarding angular stability, fabrication tolerances, and device miniaturization9. Nevertheless, despite these advances, current approaches still fall short of meeting the specific requirements for non-invasive urine bilirubin detection, where strong analyte–field interaction, robust resonance tunability, and compatibility with lossy aqueous media are crucial.

Biosensors can be categorized according to either their biological elements or transduction elements10. The biological components encompass enzymes, antibodies, microorganisms, biological tissues, and organelles11. By employing label-free optical biosensors, which convert the biological signal into interpretable optical signals, real-time monitoring and control of urine bilirubin accumulation can be achieved12. Various types of biosensors including bio-optical13, chemical-optical, bio-electrochemical, and electronic sensors have been classified and mentioned14.

Among different biosensing structures, the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors are considered the most suitable tools for analyzing interactions between various types of molecules. These structures offer benefits such as excellent sensitivity, integration capabilities, small footprint, rapid response, high accuracy, reliability, and cost-effectiveness15. The confinement and guidance of light radiation at the nanometer scale present fundamental challenges in modern nanophotonic, and surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) play a crucial role in this regard16. Surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) are electromagnetic excitations that result from the coupling between free electrons and surface oscillations in metals. The significance of SPPs lies in their ability to focus the electromagnetic field, thereby reducing the dispersion limit in nanoscale optical waves and greatly enhancing the local field amplification17. Additionally, SPPs excite plasmon emission resonances in planes that are perpendicular to the propagation direction, using either a transverse magnetic field (TM) or a transverse electric field (TE)18. Plasmonic metamaterials (PMMs) not only enable the manipulation of light properties but also offer practical advantages such as negative refractive index (RI), perfect absorbers, sub-wavelength lenses, fluorescent imaging, epsilon near zero (ENZ) phenomenon, and tunable characteristics19. ENZ nonlinear metamaterials have a significant impact on light solely at their interface with free space, positioning them as potential candidates for the design of active nonlinear nanophotonic devices20. ENZ metamaterials, a crucial category of engineered materials, are specifically designed to possess a vanishing dielectric permittivity21. In ENZ environment, propagating waves exhibit distinct phase velocities, allowing the transmission of light through sharp bends in sub-wavelength channels without any phase shift. Isotropic ENZ naturally occurs in metals such as aluminum and silver, and also in polar dielectrics like silicon dioxide and silicon carbide19.

Conversely, the utilization of photonic structures for optical devices has experienced a significant surge in recent years due to the limitations of electronic devices in meeting the growing demand for speed and minimizing power loss22. However, the diffraction limit poses a challenge for these structures in realizing integrated optical circuits. In light of this, surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) have emerged as a favorable alternative due to their dominance over the size and diffraction limit issue23. SPPs enable the manipulation of light at subwavelength scales, making them well-suited for replacement and application in this context24. Based on these principles, numerous plasmonic devices have been created using an insulator-metal-insulator (IMI) and metal-insulator- metal (MIM) structure25. Among these devices, filters, sensors, splitters, slow light waveguides, demultiplexers, logic gates, switches, converters and modulators based on plasmonic can be mentioned26. Hence, there has been great interest in designing plasmonic structures based on photonic structures to achieve a balanced trade-off in their design. Optical biosensors play a crucial role in various fields, particularly in biomedicine, disease diagnosis, blood component detection, and healthcare27. Additionally, the sensitivity of plasmon polaritons to changes in the RI has been utilized as a phenomenon and optical measurement tool28. By attaching specific particles to the metal surface, the RI can be altered, eliminating the need for labeling29. Remarkable progress in this field has overcome the limitations of conventional optical sensors, enhancing the sensitivity, accuracy, stability, and practicality of these sensors in everyday life30.

Y. Ishizaka et al. introduced a photonic-plasmonic mode converter that relied on polarization rotation and mode coupling. To achieve the desired conversion, the researchers proposed employing polarization rotation in a silicon wire waveguide featuring a defect in its upper corner. This innovative design successfully transformed the photonic TE mode input at one port into the hybrid plasmonic TM mode at the output port. The hybrid plasmonic structure in their work was constructed by incorporating silver metal beneath the defected silicon wire waveguide and a thin layer of SiO231. Gu et al. conducted a comprehensive examination of guided photonic and plasmonic modes within single-layer graphene on a large-area integrated silicon substrate and reported their findings. One key aspect of their work involved categorizing the interaction between light and the graphene material, as well as the photonic crystals of the substrate, into distinct regimes based on the consistent relationship between the photonic crystal lattice and the corresponding wavelengths. The researchers showed that optimizing the substrate design could significantly boost graphene’s absorption within the infrared spectrum through these excited resonances resonant modes32.

The resonance that results from the interaction between the incident light wave and graphene’s plasmonic waves creates a distinct peak within the transmission spectrum. The key feature of this structure is its tunability for the resonance wavelength over a wide range by making slight changes to the Fermi energy level of graphene. This property makes the device suitable for applications such as tunable optical filters or broadband modulators33. Despite these advances, a clear strategy for non-invasive urine bilirubin detection using tunable THz metamaterials integrated with nanocrystals has not yet been reported, representing the research gap addressed in this work.

It is worth noting that while invasive surgical procedures have been developed, there is growing interest in biosensors based on surface plasmonic and tunable technologies, which have demonstrated superior effectiveness and efficiency compared to surgery and invasive diagnostics. For instance, blood bilirubin level monitoring is commonly performed using invasive or minimally invasive methods34. According to the studies conducted, advancements in biosensing technologies have demonstrated the potential of plasmonic and photonic structures in various medical diagnostic applications35.

In this article, we introduce a novel approach utilizing a tunable plasmonic meta-device assisted nanocrystals engineered to interact with THz waves for non-invasive approximation of urine bilirubin accumulation. The proposed structure incorporates a tunable and highly sensitive single-band PMM configuration, which leverages the integration of engineered nanocrystals to enhance local electric-field confinement, improve resonance sharpness, and increase sensitivity. Through numerical simulations, the tunable plasmonic meta-device assisted nanocrystal’s structure demonstrates that its potential as an extremely sensitive and non-invasive approximation tool for urine bilirubin accumulation. The presented structure offers a promising avenue for enhanced medical diagnostics by providing accurate and accessible measurements of urine bilirubin levels. The following sections of the article cover structure design and semi-analytical modeling. The device’s performance as an ENZ plasmonic metamaterial, its application as a RI sensor and an all-optical switch, are studied. The use of the device for detecting urine bilirubin accumulation is also discussed, and the findings are summarized in the conclusion.

Structure design

The proposed diagnostic biosensor comprises a semi-photonic resonator consisting of silver rods enclosed within a rectangular frame also made of silver. The proposed monocrystalline environment consists of 64 silver rods arranged in an \(\:8\times\:8\) periodic lattice within an air background along the xz-plane, forming a medium with periodic dielectric properties. To generate excited resonance spectra in the semi-photonic structure, intentional defects were introduced into the periodic arrangement. These defects include the placement of rods with the same radius as the periodic ones at specific positions which break the structural periodicity (yellow rods surrounding the central region and brown rods located farther from the center). Additionally, a central rod with a radius twice that of the periodic rods and represented in red is positioned at the core of the structure. The precise configuration of this arrangement was optimized through a trial-and-error process to maximize light excitation and consequently achieve a high-quality resonance mode. It includes two embedded waveguides for input and output ports, as shown in Fig. 1(a).

The sensor is designed on a thin silicon substrate with a 40 nm height (layer thickness) and a dielectric coefficient of ε = 2.1316. The main body of the sensor has dimensions of 500 nm in length and width. The input and output terminals correspond to the overall dimensions of the sensor design (100 nm × 100 nm). To construct the structure on the silicon dielectric substrate, a 100 nm thick silver layer was initially employed, utilizing the RI data from Johnson and Christie30 and the materials in the proposed software library. In this study, the silver layer and nanocrystal materials are modeled based on the Drude–Lorentz frequency-dependent model to accurately capture their optical response. Two waveguides with equal lengths (\(\:{l}_{1}\)) were embedded at the beginning and end of the structure to effectively control and excite light. Additionally, a square waveguide with side length (\(\:{l}_{2}\)) was created and removed at the center of the silver layer to form the third waveguide and the interface between the input and output waveguides.

Following the completion of the input and output connections and the creation of the intermediate waveguide, an innovative quasi-photonic design was utilized to develop a highly efficient resonator with a high-quality factor. The resonator design involved arranging silver rods with a lattice constant (a), rod radius (r), and height (h) in an alternating pattern within the waveguide. To achieve effective filtering, defects were introduced into the quasi-photonic structure. These defects disrupted the periodicity of the structure and consisted of green and blue rods with a radius equivalent to that of the rods in the quasi-photonic structure (R1 = r). Additionally, a red-marked rod with a radius of (R2 = 2r) was placed at the center of the structure. This new design aimed to achieve extraordinary optical transmission conditions (ENZ) and enhance the excitation of resonances.

One notable advantage of this structure is its ability to achieve efficient filtering without requiring the use of nonlinear materials, thereby minimizing power consumption. Moreover, the structure exhibits excellent plasmonic switching capabilities, enabling it to serve as a diagnostic tool by detecting changes in the RI of the analyte within the sensor’s diagnostic environment. In addition to these advantages and innovations, the structure demonstrates good sensitivity, a very high-quality factor, a favorable figure of merit, and a significant increase in electric field intensity enhancement (EFIE) due to its novel design and surface characteristics. Its low cross-section makes it suitable for on-chip integration.

In summary, the design of the quasi-photonic structure incorporates a resonator ring at the center, utilizing a plasmonic structure with embedded defects to excite resonance peaks. This design plays a crucial role in achieving optimal control and excitation of light, offering favorable sensitivity (SS), quality factor (Q), figure of merit (FoM), and EFIE parameters, as mentioned earlier.

In the given equation, P represents the sensor’s output, c corresponds to the desired concentration of the analyte, ∆λ signifies the variation in wavelength, and ∆n denotes the alteration in RI. As the output of an SPR biosensor typically exhibits non-linear behavior in response to changes in analyte concentration, the sensor’s sensitivity is not uniform and fluctuates depending on the analyte concentration. This sensitivity variation necessitates the consideration of the FoM36:

The term FWHM corresponds to the acronym for full Width at half maximum. Additionally, the quality factor, Q, and EFIE can be defined as follows37:

where, the output electric field intensity is represented by \({E_0}\), while the input electric field intensity is denoted by \({E_i}\). Table 1 presents the dimensions of the metasurface plasmonic biosensor, which relies on a quasi-photonic structure. To model the sensor, CST Studio 3D-EM simulation is employed. The simulation assumes an electromagnetic plane wave propagating in the X direction, originating from input waveguide 1. Perfect electrical conductivity (PEC) is applied as the boundary condition in the Z direction, while perfect magnetic conductivity (PMC) is applied in the Y direction, with respective conditions of \({E_t}=0\) and \({H_t}=0\).

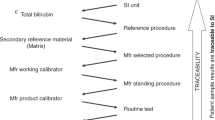

In this research work, we propose a portable microwave sensor that uses a 2.45 GHz ISM band radar to measure urine bilirubin with a non-invasive feasibility as shown in Fig. 1(b). Considering that among many identification techniques, resonance-based methods are able to immediately measure the dielectric permittivity of liquids using very simple structures, with low power consumption and cost-effective, for accurate measurement and tracking of the characteristics Resonance, such as resonance frequency, working range, or quality factor, have been of interest to researchers in order to investigate permeability changes caused by changes in the amount of bilirubin in urine with very good accuracy in measurement applications. The functionality of these structures relies on tracking of resonance characteristics such as the frequency and amplitude of the resonance. Therefore, many researchers achieve structures that are synthetic materials called metamaterials or artificial materials by engineering and optimal combination of materials. In this regard, there are many applications for these structures and many researchers have recently investigated various applications for planar resonator circuits after synthesizing artificially engineered materials as metamaterials.

Semi analytical modelling

The semi-photonic resonator layer exhibits asymmetric geometry along the x- and y-directions, which leads to distinct ECMs for TE and TM polarizations. In the TE mode, illustrated in Fig. 2(a), the incident electric field (E-field) is oriented along the y-axis. Two gaps exist between the surrounding medium and the semi-photonic resonator; however, since the E-field is parallel to these gaps, no capacitive effect is induced, and the gaps are therefore excluded from the ECM. The split-ring resonator is modeled as an impedance \({Z_1}\), with each vertical arm contributing 2\({Z_1}\). Since the arm dimensions match those of the central connecting bar, the resulting impedances are equal36, and the TE-mode ECM reduces to three parallel impedances38:

Because no capacitive discontinuities are excited in TE mode, the current distribution remains uniform along the SRR arms. Consequently, the TE resonance is dominated by the inductive–resistive behavior of the ring, resulting in weaker excited resonance compared to TM mode and a smaller resonance shift for small changes in the refractive index. This explains why TE-mode resonance is less sensitive to variations in the surrounding dielectric environment.

In the \(TM\) mode, shown in Fig. 2(b), the incident E-field is oriented along the x-axis. Here, the E-field is perpendicular to the gaps, which means the gaps behave as capacitors, each with an assumed capacitance of \(4c\). The split-ring resonator is again represented by \({Z_1}\), but each half contributes \({Z_1}/2\). Thus, the \(TM\) mode \(ECM\) reduces to a simple series connection of \({Z_1}\) and \({Z_c}\). This series combination captures the physical effect that the capacitive gaps introduce frequency-dependent phase shifts, enhancing local electric-field excited resonance. The effective conductivity of the semi-photonic resonator layer in \(TE\) mode is obtained using the Fresnel equation36:

In which \({Z_0}\), \({r^{TE}}\), \({\theta _{in}}\),\(~{\theta _{out}}\), and \({\varepsilon _{Si{O_2}}}\) denote the vacuum impedance, TE-modes reflection coefficient, incident angle, transmitted angle, and the relative permittivity of the dielectric substrate (\(Si{O_2}~layer\)), respectively. This equation links the semi-photonic layer geometry to its reflective behavior, showing how variations in the resonator dimensions or incident angle affect the observed resonance.

The corresponding impedance is the reciprocal of the conductivity38:

with

The input impedance determines the depth and position of the reflection dip. As \({Z_{{\text{in}}}}\) approaches the wave impedance of free space, destructive interference is maximized, producing the sharp excited resonance observed in TM mode.

As illustrated in Fig. 2(b), the semi-photonic resonator layer in \(TM\) mode is equivalent to a series circuit consisting of \({Z_1}\) and \({Z_c}\). Thus:

Where \({Z_c}\) is the gap capacitance impedance, \(g={\text{~}}80{\text{nm}}\) is the gap distance, \(b=100{\text{nm}}\) is the resonator width, \(\omega\) is the angular frequency, and \({\varepsilon _0}\) is the vacuum permittivity. Physically, the TM-mode excitation strongly couples to the capacitive gaps, enhancing the local electric-field excited resonance inside the resonator. This increased capacitive loading shifts the resonance to lower frequencies and significantly enhances sensitivity to refractive-index changes of the surrounding urine-analyte layer, which explains why the sensor operates with higher sensitivity under TM polarization. The term \({Z_1}\) is computed from:

The TE/TM input impedance of the metamaterial is obtained from38:

The complete structure is depicted using transmission-line segments in Fig. 3. Because the silver layer thickness is much smaller than the minimum wavelength in the simulation, the semi-photonic resonator can be modeled as a point load. In which ZuTE/TM and \({\beta _u}\) denote the \(TE/TM\) impedances of the urine fluid layer and the propagation constant of the THz electromagnetic wave traveling through the urine fluid, respectively. Their analytical forms are given below38:

The \(TE/TM\) scattering parameters, denoted as \(S_{{11}}^{{{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${TE}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{TE} {TM}}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${TM}$}}}}\), representing the return losses of the metamaterial, are obtained

Where \(Z_{{in}}^{{{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${TE}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{TE} {TM}}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${TM}$}}}}\) is derived from Eqs. (13) and (14). The \(TE/TM\) reflections of the metamaterial, denoted as \({R^{{\raise0.7ex\hbox{${TE}$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{TE} {TM}}}\right.\kern-0pt}\!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${TM}$}}}}\), can be calculated using33:

These expressions link the ECM to measurable resonance spectra. The sharper TM-mode reflection dip arises from the stronger capacitive coupling in the SRR, validating the semi-analytical model and supporting the full-wave simulation results.

Operation as ENZ plasmonic metamaterial

Figure 4 depicts the optical response of the proposed PMM biosensor across the 280 to 360 THz frequency range, showcasing the relationship between its magnetic permeability (µ) and electrical permittivity (ε). As shown, both µ and ε approach zero at specific wavelengths, 1034, 1000, 950, and 909 nm, which correspond to frequencies of 290, 300, 315, and 330 THz, respectively. Consequently, based on Fig. 4, it can be inferred that the proposed metamaterial sensor exhibits ENZ characteristics at the desired resonance peak, specifically at 950 nm.

The incorporation of structures with near-zero permeability characteristics introduces a range of distinct attributes to conventional photonic systems. These attributes include the ability to isolate spatial and temporal field changes, establish tunneling conditions through arbitrary channels, achieve constant phase transitions, and enable strong excitation of light resonance and ultra-fast phase transitions. ENZ metamaterials possess unique absorption resonances, making them highly valuable in biosensor design, particularly in medical applications37. The integration of semi-photonic conditions and the plasmonic properties in the proposed sensor’s design generates the ENZ feature, which is a novel and significant parameter. This characteristic results in increased electric current intensity within the ENZ environment compared to free space, leading to enhanced light absorption. This heightened optical absorption within the ENZ environment facilitates polarization control and effective filtering within the structure.

Considering Maxwell’s equations and the theory of electromagnetic waves, two important parameters in continuous media and metamaterials are electrical permittivity (\(\varepsilon\)) and magnetic permeability (\({\text{\varvec{\upmu}}}\))38, with the help of these two parameters, the optical properties of materials can be fully described. In addition to assigning positive and negative values, the adaptation of zero value for epsilon by using the design of suitable structures to control the interaction of light with matter as much as possible to achieve field concentration and transfer with a fixed phase has received much attention. In this regard, it is easy to achieve zero epsilon values by combining and changing structures appropriately, and this manipulation of epsilon by changing the structure is much easier than changing of \({\text{\varvec{\upmu}}}\). With the realization of this phenomenon according to the relation, in fact, we achieve a RI with a value of zero, which is the possibility of controlling the amplitude and phase of the waves, strong discontinuities in the normal electric field and the creation of a resonant field, and finally, the possibility of engineering. It realizes optical structures and the acquisition of information processing chips with very high speed and future applications in integrated photonic devices39,40,41.

In here, we present a novel approach for optimizing an all-optical environment by utilizing nano-rod antennas embedded in a semi-photonic medium attached to a thin ENZ material. The mentioned approach enables us to develop a metasurface optical sensor with a narrow absorption single-band spectrum. The proposed structure includes a resonator ring located at the center of the intermediate waveguide within the receiver of the semi-photonic structure, serving as a bright plasmonic mode. When the proposed structure is exposed to a signal source with frequency ω, an intense coupling between magnetic plasmon polaritons and incident light is established. The coupling leads to the excitation and confinement of resonances across different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum within the sensor structure.

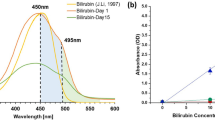

Figure 5(a) illustrates the absorption and reflection spectra of the proposed sensor, where a strong absorption occurred at a wavelength of 950 nm, which corresponds to the excited resonance mode supported by the periodic nanostructure. By employing a symmetrical design of three waveguides, the excitation of light not only induces excitation of the electromagnetic field along the x-axis, but also triggers the excitation of guided resonance modes around 950 nm, enhancing field localization near the nanocrystals. As a result, a robust coupling of light with matter occurs and creates a very strong field dipole as shown in Fig. 5(b). This strong coupling gives rise to a prominent and high-quality resonance at the 950 nm wavelength. Figure 5(a), rendering the proposed sensor an efficient absorber within the specified range.

In addition to its absorptive capabilities, the microwave metamaterial sensor can function as a sensor based on the ENZ feature. Putting materials with different refractive indices into the proposed structure shifts the absorption’s excited resonance frequency. Figure 6 shows the absorption of the proposed structure for different values of RI in the sensing medium. By increasing the RI the resonance wavelength shifts to longer wavelengths (red shift).

Refractive index sensor

Recently, there has been considerable interest in near-infrared (NIR) optical biosensors in the biomedicine field because of their outstanding performance. These biosensors, which are based on plasmonic nanostructures, have gained popularity due to their low cost and high integration capability. They have found increasing applications in biomedicine, particularly in the detection of substances and biomarkers related to human health. Additionally, they have been highly regarded for their effectiveness in treatment and care without requiring specialized expertise from the patient42. Figure 7 shows the absorption spectrum of the sensor for changes in different refractive indices of the substrate with a step of 0.1 change in the RI. Increasing the substrate’s refractive index, ns, causes a red shift in the resonance wavelengths of the transmitted spectra. Figure 7 presents the histogram and distribution of the sensors’ sensitivity and FoM for the substrate RI changes in steps of 0.1 nm. As shown in the figure, both the sensitivity and the FoM exhibit a nearly uniform and well-distributed pattern. Furthermore, as shown, a RI value of 0.2 for the structure yields the highest sensitivity and the best FoM, reaching values of 325 nm/RIU and 65 nm/RIU, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7, increasing the RI variation leads to a reduction in both sensitivity and FoM, and an RI change of 0.2 in the sublayer represents the optimal condition. Moreover, to ensure the practical reliability of the proposed sensor under real-world operating conditions, we conducted a comprehensive stability analysis by evaluating the device response at different temperature levels. Across all tested temperatures, the distribution patterns of both sensitivity and the figure of merit remain nearly identical to the baseline case, exhibiting consistent peak positions and minimal deviation in their statistical spreads. This uniformity confirms that the resonance wavelength associated with Δn = 0.2 retains its accuracy and robustness even under thermal fluctuations. Consequently, the stability results validate that the sensor maintains reliable detection capability in practical biomedical environments, where unavoidable changes in temperature and biological sample conditions—such as urine variability—may occur.

In the following, according to Fig. 8, we will analyze the strength of the magnetic field to further investigate the properties of the structure. We use the magnetic field to explain how magnetic forces behave both in the surrounding space and within a magnetic material. Specifically, the magnetic field vector indicates the magnitude and direction of the force on a given object. Magnetism and magnetic fields are aspects of the electromagnetic force, which is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. Therefore, magnetic field lines are an effective way to show the direction of the field. The surface current distribution at the resonance frequencies of the metamaterial absorber of the proposed structure is illustrated in Fig. 8. At the resonant frequencies shown in Fig. 8, the structure generates surface currents, forming magnetic dipoles. As shown in Fig. 8, in the places where the pole is formed, there is an increase in the field at the entrance and exit of the waveguide and a decrease in the magnetic field on the opposite side and the other side of the formation of the poles, that is, the top and bottom of the waveguide. As depicted in Fig. 9, when the irradiation angle ranges change from 0 to 50 degrees, we observe output and resonance peaks at a wavelength of 950 nm. Once the angle exceeds 50 degrees, the switching mechanism is triggered, resulting in zero output. One notable advantage of the proposed design is its simplicity, as it does not require increased power or rely on nonlinear and Kerr effects. Figure 10 shows the output of the electric field to the input power of the source which is drawn next to the absorption diagram of the structure. The left side of the diagram displays the EFIE, while the right side illustrates the absorption. As it is known, the intensity of the output electric field increases significantly compared to the input, and the value of increase, that tends toward the infrared region, is 1714. The notable rise in the EFIE is attributed to the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) occurring near the nanorods.

Urine bilirubin diagnosis

Generally, glucose, albumin, urea, and bilirubin are among the major biochemical components that may appear in urine. Among these components, bilirubin is of particular clinical importance because its presence in urine is an indicator of liver dysfunction and is not observed under normal physiological conditions. Therefore, this study focuses specifically on the measurement of bilirubin concentration in urine.

Table 2 presents the refractive index values corresponding to urine samples containing different concentrations of bilirubin, which were used to evaluate the sensing performance of the proposed structure.

Bilirubin is a by-product of old broken red blood cells, a pigment that has a distinct yellow color to bile. It is a toxic compound, so should be excreted out of the body43. Excessive bilirubin in the bloodstream causes the whites of the eyes and yellowing of the skin, a condition known as jaundice, and makes stool and urine colored. Bilirubin is broken down in the liver, combined with bile, and then excreted in the bile duct and stored in the gallbladder. On the other hand, conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in adults may be a sign of a dangerous condition, therefore, in addition to a blood test, a bilirubin urine test is performed and analyzed as part of a comprehensive urine test, which can be part of a health checkup44. In this research work, we investigate the optimal response capability of the proposed single-band metamaterial multi-functional sensor and extract the absorption spectrum of the structure. Figure 11 shows the 3-D plot of the single-band strong absorber structure’s absorption spectrum in terms of wavelength for different values of the RI of the substance under test, i.e. the level of urine bilirubin concentration.

As shown in Fig. 11, measuring the RI of urine with varying bilirubin levels reveals that the increasing RI causes a shift in the resonance peak, allowing us to identify and measure the bilirubin concentration. The effective RI (neff), dependent on the fundamental frequency in different concentrations of bilirubin in reference45. when the RI increases with the change of bilirubin concentration in urine the absorption spectrum of the surface plasmonic structure towards the wavelength Higher values mean red shift. Therefore, the absorption window of the presented plasmonic structure strongly depends on the RI of the measured material.

Recent studies on metamaterial-based biosensing have primarily explored the sub-terahertz (GHz to low-THz) frequency range, reporting notable sensitivity within their respective domains8,9. These works provide valuable insights into the design and optimization of metamaterials for biosensing applications. However, the present study focuses on the optical-terahertz range, where different physical mechanisms, particularly plasmonic resonances in ENZ metamaterials, govern the device performance.

Table 3 compares various metamaterial structures used for THz biosensing, focusing on key parameters such as operating wavelength, SS (nm/RIU), Q, EFIE and FoM of the proposed sensor with another THz biosensor. The data illustrate that the proposed structure in this work, operating at a wavelength of 952 nm, exhibits superior performance in terms of sensitivity and electric field enhancement compared to previous designs. Specifically, the proposed sensor achieves a sensitivity of 325 nm/RIU and an EFIE of 1714, outperforming many of the existing metamaterial sensors. The significant improvement in performance metrics like sensitivity and FoM indicates the promise of this metamaterial structure for real-world biomedical diagnostics.

Conclusion

In this research, we have designed and analyzed a novel, practical surface PMM structure integrated with a semi-photonic resonator for the non-invasive detection of bilirubin in human urine. The incorporation of a single nanocrystal in each unit cell enhances the local field confinement without altering the modal nature of the resonance.

Our proposed sensor demonstrated exceptional performance in terms of sensitivity, quality factor (Q), figure of merit (FoM), and EFIE, making it highly suitable for THz biosensing applications. The results indicate that with an operating wavelength of 952 nm and a sensitivity of 325 nm/RIU, the sensor outperforms many previously designed biosensors, especially in its ability to detect minute changes in bilirubin concentration. The proposed sensor not only achieved a high degree of sensitivity but also displayed remarkable versatility, with potential applications extending beyond bilirubin detection to other medical diagnostic areas. The integration of metamaterials with ENZ characteristics further enhanced the performance by enabling strong field confinement and reduced power consumption, with the specific choice of silver and the nanocrystal geometry playing a critical role in the modal behavior and absorption efficiency.

By analyzing the absorption spectra and refractive index shifts, it is evident that the sensor exhibits a clear red shift with increasing RI of the urine samples, and the optimal substrate RI of 0.2 provides the highest sensitivity and FoM, confirming the design’s suitability for precise biomedical sensing.

The ability to miniaturize the sensor while maintaining high accuracy paves the way for its application in portable, low-cost, non-invasive diagnostic devices that can be deployed in a variety of clinical environments. However, like all studies, this research faces certain limitations. By addressing these limitations, the proposed metamaterial-based biosensor could revolutionize non-invasive diagnostic technologies, offering reliable, fast, and accessible healthcare solutions.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Creeden, J. et al. Bilirubin as a metabolic hormone: the physiological relevance of low levels. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metabol. 320 (2), 191–207 (2021).

Turgeon, M. Clinical Hematology: Theory and Procedures (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005).

Farag, M., Ashraf, A. M., Elfeky, A. & Salem, A. M. Sensitive assessment of bilirubin using various color space signals derived from captured images of microfluidic paper-based analytical devices. Talanta Open 2024, 100323 (2024).

Hulzebos, C. et al. Screening methods for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia: benefits, limitations, requirements, and novel developments. Pediatr. Res. 90 (2), 272–276 (2021).

Taha, B. A. et al. Plasmonic-enabled nanostructures for designing the next generation of silicon photodetectors: trends, engineering and opportunities. Surfaces Interfaces 2024, 104334 (2024).

Rafighirani, Y., Javidan, J. & Heidarzadeh, H. Polarization-independent tunable multi-band terahertz absorber based on graphene structure to design the ultra-high sensitive biosensors. Phys. Scripta 99, 075014 (2024).

Rafighirani, Y. & Javidan, J. Revolutionizing early cancer detection: graphene-based terahertz biosensors for precision diagnostics. Plasmonics 2025, 1–10 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. Multifunctional terahertz biodetection enabled by resonant metasurfaces. Adv. Mater. 37 (16), 2418147 (2025).

Wang, R., Song, L., Ruan, H., Zhang, X. & Chang, C. Recent progress in high-performance terahertz biosensors: challenges and perspectives. Adv. Mater. 37, 2411490 (2025).

Kaur, H., Aakash, B. & Shrivastav, S. Biosensors: classification, fundamental characterization and new trends: a review. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 8 (6), 315–333 (2018).

Shanbhag, M., Manasa, G., Ronald, J. M., Kunal, M. & Shetti, N. P. Fundamentals of bio-electrochemical sensing. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 16, 100516 (2023).

Geetha, M. et al. Futuristic approach to cholesterol detection by utilizing Non-invasive techniques. Curr. Biotechnol. 12 (2), 79–93 (2023).

Arora, N. Recent advances in biosensors technology: a review. Octa J. Biosci. 1, 2 (2013).

Malik, S. et al. Nanomaterials-based biosensor and their applications: a review. Heliyon (2023).

Farshchi, F. & Hasanzadeh, M. Microfluidic biosensing of circulating tumor cells (CTCs): recent progress and challenges in efficient diagnosis of cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 134, 111153 (2021).

Zayats, A. V., Igor, I. S. & Maradudin, A. A. Nano-optics of surface plasmon polaritons. Phys. Rep. 408, 3–4 (2005).

Anwar, R. S., Huansheng, N. & Mao, L. Recent advancements in surface plasmon polaritons-plasmonics in subwavelength structures in microwave and Terahertz regimes. Digit. Commun. Netw. 4 (4), 244–257 (2018).

Iqbal, T. Coupling efficiency of surface plasmon polaritons: far-and near-field analyses. Plasmonics 12, 215–221 (2017).

Ghobadi, H., Jafari, Z. & De Leon, I. Epsilon-near-zero plasmonics. In Plasmon-Enhanced Light-Matter Interactions 27–55 (Springer International Publishing, 2021).

Reshef, O., Israel, D. L., Zahirul, A. M. & Boyd, R. W. Nonlinear optical effects in epsilon-near-zero media. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4 (8), 535–551 (2019).

Li, Y., Ziheng, Z., Yijing, H. & Li, H. Epsilon-Near-Zero Metamaterials (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Tong, X. C. Advanced Materials for Integrated Optical Waveguides, vol. 46 (Springer International Publishing, 2014).

Bertolotti, M., Sibilia, C. & Guzman, A. Applications of plasmons. In Evanescent Waves in Optics: An Introduction to Plasmonics 169–208 (Wiley, 2017).

Stockman, M. I. et al. Roadmap on plasmonics. J. Opt. 20 (4), 043001 (2018).

Kazanskiy, N. L., Khonina, S. N. & Butt, M. A. Plasmonic sensors based on metal-insulator-metal waveguides for refractive index sensing applications: a brief review. Phys. E: Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostruct. no. 117, 113798 (2020).

Butt, M. A., Svetlana, N. K. & Kazanskiy, N. L. Recent advances in photonic crystal optical devices: a review. Opt. Laser Technol. 142, 107265 (2021).

Haleem, A., Javaid, M., Singh, R. P., Suman, R. & Rab, S. Biosensors applications in medical field: a brief review. Sens. Int. 2, 100100 (2021).

Heydari, M., Habibzadeh-Sharif, A. & Jabbarzadeh, F. Design of a compact refractive-index sensor based on surface plasmon polariton slot waveguide. Photon. Nanostruct. Fundam. Appl. 38, 100755 (2020).

Xu, Y. et al. Optical refractive index sensors with plasmonic and photonic structures: promising and inconvenient truth. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7 (9), 1801433 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Sensors for the environmental pollutant detection: are we already there? Coord. Chem. Rev. no. 431, 213681 (2021).

Ishizaka, Y., Nagai, M., Fujisawa, T. & Saitoh, K. A photonic-plasmonic mode converter using mode-coupling-based polarization rotation for metal-inserted silicon platform. IEICE Electron. Express. 14 (2), 20160989–20160989 (2017).

Gu, T. et al. Photonic and plasmonic guided modes in graphene–silicon photonic crystals. Acs Photonics 2 (11), 1552–1558 (2015).

Gao, W., Shu, J., Qiu, C. & Xu, Q. Excitation of plasmonic waves in graphene by guided-mode resonances. ACS Nano. 6 (9), 7806–7813 (2012).

Halder, A. et al. A novel whole spectrum-based non-invasive screening device for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 23 (6), 2347–2353 (2019).

Uniyal, A., Srivastava, G., Pal, A., Taya, S. & Muduli, A. Recent advances in optical biosensors for sensing applications: a review. Plasmonics 18, 735–750 (2023).

Hamooleh Alipour, A. & Mir, A. Design and simulation of a high-selective plasmon-induced reflectance in coupled dielectric-metal-dielectric nano-structure for Senor devices and slow light propagation. Plasmonics 14 (2), 511–521 (2019).

Farmani, A., Miri, M. & Sheikhi, M. H. Analytical modeling of highly tunable giant lateral shift in total reflection of light beams from a graphene containing structure. Opt. Commun. 391, 68–76 (2017).

Rahmanzadeh, M., Rajabalipanah, H. & Abdolali, A. Multilayer graphene-based metasurfaces: robust design method for extremely broadband, wide-angle, and polarization-insensitive terahertz absorbers. Appl. Opt. 57 (4), 959–968 (2018).

Cheng, D. K. Field and Wave Electromagnetics (Pearson Education India, 1989).

Qin, F., Peng, M., Estevez, D. & Brosseau, C. Electromagnetic composites: from effective medium theories to metamaterials. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 10 (2022).

Achanta, V. G. Surface waves at metal-dielectric interfaces: material science perspective. Rev. Phys. 5, pp100041 (2020).

Ciminelli, C., Francesco, D., Donato, C. & Nicola Armenise, M. Integrated photonic and plasmonic resonant devices for Label-Free biosensing and trapping at the nanoscale. Phys. Status Solidi (a). 216 (3), 1800561 (2019).

Kaplan, M., Bromiker, R. & Hammerman, C. Hyperbilirubinemia, hemolysis, and increased bilirubin neurotoxicity. Semin. Perinatol. 38, 429–437 (2014).

Osiak, W., Wątroba, S., Kapka-Skrzypczak, L. & Kurzepa, J. Two faces of heme catabolic pathway in newborns: a potential role of bilirubin and carbon monoxide in neonatal inflammatory diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2020, 7140496 (2020).

Fan, S. L. & Bai, S. Urinalysis. In Contemporary Practice in Clinical Chemistry 665–680 (Academic, 2020).

Patel, S. K., Parmar, J., Sorathiya, V., Nguyen, T. K. & Dhasarathan, V. Tunable infrared metamaterial-based biosensor for detection of hemoglobin and urine using phase change material. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–11 (2021).

Alipour, A., Mir, A. & Farmani, A. Ultra high-sensitivity and tunable dual-band perfect absorber as a plasmonic sensor. Opt. Laser Technol. 127, 106201 (2020).

Alipour, A., Forouzeshfard, M. & Baghbani, R. Blood hemoglobin concentration sensing by optical nano biosensor-based plasmonic metasurface: a feasibility study. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 21, 620–628 (2022).

Vafapour, Z. et al. The potential of refractive index nanobiosensing using a multi-band optically tuned perfect light metamaterial absorber. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 13786–13793 (2021).

Verellen, N. et al. Plasmon line shaping using nanocrosses for high sensitivity localized surface plasmon resonance sensing. Nano Lett. 11, 391–397 (2011).

Sadeghzadeh, L. E., Vafapour, Z. & Ghahraloud, H. Optically tunable triple-band perfect absorber for nonlinear optical liquids sensing. IEEE Sens. J. 20 (17), 10130–10137 (2020).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Azizmorad Valinasab conducted the study, performed all simulations, and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. Ali Mir proposed the original concept, critically evaluated the results, and played a key role in the final revision of the manuscript. The other co-authors contributed by supervising the simulation and analysis of the results and reviewing the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Valinasab, A., Mir, A., Mehrdad, V. et al. A terahertz metamaterial biosensor using nanocrystals for noninvasive urine bilirubin diagnosis. Sci Rep 16, 1413 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31521-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31521-0