Abstract

This study aimed to develop a 4-week volleyball-specific training program for the unique movement requirements of volleyball to enhance performance and reduce injury risk among adult players. Sixteen male participants were college players with at least 10 years of volleyball experience (ages: 18–22 years). Participants performed spikes in pre- and post-test, starting with a 5 m run-up from the left side of the net to a force platform. They underwent a four-week training program aimed at improving spike performance. The analyzed variables included the center of mass (COM), joint angles, angular velocities, moments, ground reaction forces (GRF), and forces in the three planes of the knee joint. For statistical analysis, paired t-tests and statistical parametric mapping (SPM) were employed to evaluate pre- and post-test differences in the measured variables (α = .05). During the jumping phase, knee extension angular velocity and peak vertical GRF increased after training (p < .05), and SPM analysis revealed a higher knee flexion moment between 40 and 80% of the phase post-test (p < .001). In the airborne phase, the center of mass (COM) reached a greater height after the training program (p < .05). During the landing phase, the minimum COM height decreased post-test (p < .05), while flexion angular velocity increased (p < .05). In addition, the extension moment and vertical joint forces of the knee were reduced (p < .05), and vertical GRF remained consistently high at 35% of the landing phase (p < .001). The four-week specific training program effectively enhanced jump performance and reduced knee joint load, promoting both improved performance and safer landing mechanics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During attacking volleyball, player proficiency in executing the spike is a pivotal factor contributing to match success. The spike is a distinct skill, demanding intricate coordination of various body joints and is performed based on biomechanical principles during the jumping, airborne, and landing phases1,2,3. Successful performance of the volleyball spike involves initial horizontal movement speed development during the approach phase, which decelerates just before the jump4. Upon contacting the left foot, movement is converted into vertical acceleration. Lower limb muscles are vital during the spike jump, facilitating an explosive push-off via a stretch–shortening cycle, which involves an eccentric contraction followed by a swift concentric contraction. Consequently, maximum rotation is achieved in the trunk and shoulder movements, allowing for an intensely powerful spike2,5,6. However, spike performance failure can result from joint coordination, lower limb joint angles, and ground reaction force (GRF) factors, leading to a timing mismatch with the tossed ball during the airborne phase7,8.

Elite volleyball players are known to perform approximately 40,000 spikes per season to enhance their skill levels and improve their success rates9,10. However, according to a previous U.S. epidemiological study examining injuries in volleyball players, over 90% of chronic injuries affected the lower extremities, with knee injuries being the most prevalent, accounting for 61% of such incidents11,12. Interestingly, for a single-leg landing technique after a spike shot, most volleyball players can generate an impact of up to seven times their body weight. Without proper movements to absorb the shock applied to the lower extremity joints, such repetitive loading could lead to various injuries such as tibial or fibular stress fractures, patellar tendinopathy, chondromalacia, and lumbar spinal injury11,13,14. Therefore, to prevent such injuries and facilitate a stable landing after a spike, it is essential for players to execute coordinated and balanced movements of the lower extremity joints, underscoring the necessity of developing a specific training program11,13.

Previous studies have verified the reduction of knee injuries in athletes performing volleyball spikes by applying for various training programs. These include plyometric, core stability training, jump training, balance training for volleyball players15,16. However, these studies often employed conventional training programs rather than those tailored specifically to the requirements of volleyball and did not directly assess the skills and performance associated with volleyball spikes or spike jumps. Using generalized exercise programs and evaluating functional balance and strength makes it challenging to quantify the correlation in terms of effectiveness between these programs and improvements in skill level and performance17. Therefore, we need a specialized training program that can maximize performance in a shorter period rather than training over a long period of time. Furthermore, kinematic and kinetic evaluations related to volleyball spiking techniques are essential for improving players’ spike performance and preventing knee injuries1,18. It is essential to help athletes maintain high performance over an extended period and have a healthy athletic career. Therefore, the practical training and scientific evaluations conducted through this study are expected to significantly contribute to developing and applying new training methods for athletes.

The objective of this study is to develop a four-week, specific training program aimed at performance enhancement and injury prevention for adult volleyball players. We will implement this program and examine its effect on the kinematic and kinetic variables of the knee joint during the jumping and landing phases of the volleyball spike. This program will be implemented, and its effects on kinematic and kinetic variables of the knee joint during the jumping and landing phases of the volleyball spike will be examined. We hypothesize that volleyball players will exhibit enhanced kinetic factors in their knee joint during the jumping phase, resulting in increased spike jump height during the airborne phase. Additionally, we expect an improvement in knee joint strength through the training program, thereby reducing the load on the knee joints. By addressing specific movement patterns and their impact on joint mechanics, the findings could offer valuable insights for developing more effective training regimens and injury prevention strategies in the field of sports science.

Methods

Participants

Sixteen right-handed male college volleyball players, all playing as outside hitters (left-side position), participated in this study; they had 10.25 ± 0.58 years of volleyball experience (age: 19.56 ± 1.55 years, height: 1.90 ± 0.06 m, weight: 76.66 ± 7.05 kg, BMI: 21.26 ± 1.35; Table 1). The sample size was determined based on a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (t-test model) with data from a pilot study of 4 participants19. The analysis assumed a medium effect size (Cohen’s dz = 0.5), an alpha level of 0.05, and a desired power of 0.80, which indicated that the current sample size would provide adequate statistical power for detecting expected biomechanical changes. No corrections for multiple comparisons were applied, as each outcome variable was analyzed independently. Furthermore, previous studies investigating biomechanical changes in volleyball performance have successfully used similar sample sizes, supporting the adequacy of our design20,21. Potential sources of bias include selection bias from recruiting a single college team and individual variability in training history and physical condition. Participants were advised to refrain from excessive physical activity 24 h before the study commenced, and the study’s purpose and procedures were thoroughly explained on the day of participation. After giving their informed consent via a signed form, the players participated in all the procedures of this study, which were all approved by the institutional review board (KNUE-202302-BM-0487–01). And the study protocol was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for participants were 1) at least ten years of volleyball experience, 2) attackers, and 3) players who had not experienced any lower limb joint injuries in the past six months and express a willingness to participate. Additionally, 1) players currently injured, 2) those who refused to participate were excluded from this study.

Apparatus

We utilized a 3D motion capture analysis system, deploying 12 infrared (IR) cameras (Oqus 7 +; Qualisys, SWE) and two force platforms to measure GRF (Type 9260AA6; Kistler, SWI). Additionally, we attached a total of 61 reflective markers to the skin at major joint and segment points on the upper and lower extremities. The placement of these reflective markers was as follows: joint markers were attached to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), sacrum, shoulder, elbow, knee, and ankle joints, while trajectory markers were affixed to body segments such as the head, trunk, upper arm, lower arm, thigh, shank, and foot22 (Table 2). A calibration was carried out to establish a global coordinate system within the IR camera. The IR camera’s sampling rate was 150 frames per second, while the force platform’s rate was 1,500 Hz. Before data acquisition, both static and dynamic calibrations were performed to define the position and orientation of the capturing volume and to minimize the lens distortion of each camera. The capture volume was calibrated in the size of 2.7 m (width) \(\times\) 7.5 m (length) \(\times\) 3.5 m (height) prior to data acquisition (error set to less than 0.5 mm). Two force plates were synchronized with the Qualisys system to identify spike events and GRF.

Procedures

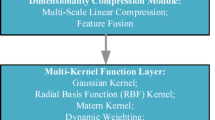

The methodology used in this study was implemented in three stages: a pre-test, a four-week specific training program, and a post-test (Fig. 1 left).

Upon arrival at the laboratory, participants were equipped with standardized experiment attire and shoes, and reflective markers with a diameter of 1.2 cm were affixed to the midpoints of body joints and lower-extremity segments. The spike motions commenced with a run-up length of 5 m behind the nets, employed for the evaluation of GRF, with each player striking the tossed ball directly. A successful spike attempt was primarily defined based on objective criteria: the ball landing within the pre-determined target zone (2 m × 2 m), correct step sequence, and accurate forceplate contact. Expert qualitative judgment by three experienced volleyball coaches was used only as a supplementary check to confirm that the spiking technique was executed properly, with jump height, hit position, and ball speed considered23. If a trial did not meet any of the objective criteria, it was considered a failure regardless of the coaches’ evaluation. Data was collected from five successful spike trials that fulfilled these conditions.

Following the pre-test, all participants proceeded with a tailored specific training program after a day of rest (A total of 20 sessions, excluding weekends). This program was developed considering the frequency of the players’ spiking technique usage, injury characteristics by position, and extent of knee joint injury24,25,26. In designing the program, potential risk factors during training were minimized by prioritizing weight-bearing exercises over intensive muscle strength activities. Additionally, exercises aimed at enhancing fine motor skills around the knee joint and effective stimulation of the patellar tendon through eccentric exercises for the quadriceps muscles were primarily incorporated into the program (Table 3)27,28,29,30,31,32. To ensure consistency and control for variables within the study design, a standardized protocol was applied uniformly to all participants throughout the 4-week intervention period. The exercise selection, sets, repetitions, and intensity remained constant, with the primary goal of mastering the movement patterns and ensuring consistent neuromuscular stimulation rather than implementing progressive overload. Adherence was monitored by having all participants record their attendance and completion of all sets for each training session. Only data from participants who demonstrated an adherence rate of 100% were included in the analysis. The training program was conducted thrice a week for four weeks, with a 3-min resting interval incorporated after each set27. And after participating in a 4-week training program, the participants performed a post-test after a day of rest.

Data processing

Utilizing the attached markers and GRF data of the participants, kinematic and kinetic variables were extracted using Visual3D software (C-Motion Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). For kinematics data, spline interpolation up to 10 frames and a Butterworth 4th order low-pass filter at a cut-off frequency of 10 Hz was applied12. The kinetics data were filtered using a Butterworth 4th order low-pass filter at a cut-off frequency of 50 Hz1. Spike motion was categorized into three distinct phases: the jumping phase, the airborne phase, and the landing phase. The jumping phase was defined as the period from the initial contact of the right foot with the ground (vertical GRF exceeding 10 N) to the point when the right leg take-off the ground before the jump (vertical GRF below 10 N); the airborne phase was defined as the period from when right leg leave the ground until the left foot contact with the ground. The landing phase was defined as the duration from the left foot’s contact (vertical GRF exceeding 10 N) to the point of maximal knee flexion in the sagittal plane3,6,7,12. For single-leg landings, this maximum flexion referred to the left knee, while for double-leg landings, it was defined as the point when the knee of either leg reached its maximal flexion, i.e., the later of the two knees (Fig. 2).

Since volleyball spikes require maximum force in each phase with the explosive jump, the maximum value was calculated for each phase in this study. The subsequent variables were computed referencing the specific events and phases. Firstly, for the COM position, the lowest COM height during jumping in the jumping phase and the peak height in the airborne phase were calculated5. As for the knee joint angles, the maximum angles of left/right flexion, abduction, and internal rotation were determined during the jumping and landing phases, and for the angular velocity, the maximal velocity of flexion, extension, abduction, and internal rotation was computed1. Among the kinetic variables, the internal joint moments of flexion, adduction, and external rotation were identified during the jumping phase, while internal joint moments of extension, abduction, and internal rotation were identified during the landing phase. The peak values in the vertical GRF were derived for both the jumping and landing phases7. Finally, joint forces were measured, intersegmental 3D dominant limb knee joint forces were obtained by submitting the filtered 3D kinematic and GRF data to a conventional inverse dynamics analysis33,34. The 3D intersegmental knee joint forces (anterior–posterior, medial–lateral, and vertical direction) were transformed to the tibial reference frame for interpretation and analysis and normalized in accordance with subject body mass data34.

Statistical analysis

All variables were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA), and results were presented as mean and standard deviation. A paired t-test was conducted to investigate the kinetic and kinematic differences in spike motions before and after the training. We ensured that the assumptions of normality for the paired t-tests were met for both pre- and post-test data. Normality testing was conducted using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the results indicated that the data followed a normal distribution (p > 0.05). Therefore, we proceeded with paired t-tests to analyze the differences between pre- and post-test measurements. And Cohen’s dz was used to evaluate the effect size. Cohen defines dz of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 as small, medium, and large effects, respectively, and effect size dialogs are available to compute the appropriate effect size parameter from means and SDs35. Moreover, for the statistical analysis of biomechanical time series, a paired t-test was executed using SPM1D, a software package dedicated to one-dimensional statistical parametric mapping (SPM)36,37. We evaluated time-normalized kinematic and kinetic variables using SPM to better understand spike motion, covering the period from ground contact at take-off to maximum knee flexion in the jumping and landing phase38. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to evaluate the heterogeneity of the standardized effects39. In terms of testing time points in accordance with the time series sequence, Matlab 2023 (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) was employed. Lastly, the significance level for all variables was established at α = 0.05.

Results

Kinematic and kinetic variables

Table 4 presents the results from analyzing the maximum and minimum vertical positions of the COM and horizontal velocity components during the volleyball spike. The minimum COM height was reduced in the jumping phase, while the peak height was augmented in the airborne phase (minimum height: t = −5.054, p < 0.001, Cohen’dz: 1.76; peak height: t = 2.426, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 0.97). During the landing phase, a lower minimum COM height was observed post-test (t = −6.134, p < 0.001, Cohen’dz: 1.26). The knee joint’s extension angular velocity was increased in the jumping phase (t = 2.546, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 0.91), while the flexion angular velocity was increased in the landing phase (t = −2.696, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 1.73).

In the jumping phase, the peak vertical GRF was increased in the post-test (t = 2.559, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 0.86), while the flexion moment was also increased (t = −2.318, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 0.90). However, the extension moment was decreased in the landing phase (t = −4.402, p < 0.001, Cohen’dz: 1.72). The AP and vertical joint forces of the knee joint were increased post-test in the jumping phase (AP: t = 3.727, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 1.60; V: t = −2.477, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 0.83), but these forces were decreased during the landing phase (AP: t = −2.938, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 1.17; V: t = 3.040, p < 0.05, Cohen’dz: 1.35).

Statistical parametric mapping

The SPM analysis during the jumping phase of the spike revealed a difference in the flexion moment in the 40–80% segment of the period on the sagittal plane (t = 3.622, p < 0.001), while the vertical joint force showed an increase post-test compared to pre-test in the 29–84% phase (t = 3.863, p < 0.001, Fig. 3). Additionally, vertical GRF was consistently larger in the segment from 35% (t = 3.287, p < 0.001).

Mean kinematic and kinetic patterns of jumping (right leg) and landing phase (left legs) for the pre-test (red line), post-test (blue line) and time-dependent F-values of the SPM (primary statistical test; analysis of variance) for all subjects (dashed redlines—p =.05). Gray area indicates a region with statistically significant differences.

In the landing phase, the SPM analysis displayed that the vertical GRF of post-test values was lower by 0–55% compared with the pre-test (t = 3.287, p < 0.001). The value of AP joint force was lower immediately after landing (t = 3.409, p < 0.05), while the vertical joint force was decreased in the 30–78% phase (t = 3.216, p = 0.001).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to devise a four-week "volleyball-specific training program" intended to augment performance and prevent injuries among adult volleyball players. To achieve this objective, participants underwent a 4-week specific training program, and kinematic and kinetic data were collected and analyzed during pre- and post-test. The findings of this study confirmed the kinematic and kinetic movements of the knee joint involved in achieving high jump height during the jumping phase by the specific training program.

Jump performance—kinematic variables

The observed increase in knee extension angular velocity and COM height during the jumping phase indicates that the specific training program effectively enhanced lower limb muscular strength and coordination. This aligns with previous research showing that higher knee angular velocity contributes to greater jump height7,8,40, but our study further suggests that targeted hop jump and plyometric exercises improve temporal coordination of the trunk and extremities during the airborne phase, which likely facilitated more accurate spike execution. These findings highlight not only the importance of muscular power but also the role of coordinated segmental timing in optimizing jump performance, offering practical insights for volleyball-specific training7,9,41.

Jump performance—kinetic variables

To examine the effect of the specific training program on jump performance, kinetic variables including GRF, joint moment, and joint forces were analyzed. The results indicate that the hop jump series effectively increased peak vertical GRF, flexion moment, and vertical joint forces, reflecting improved lower limb muscular strength and coordination42,43. These kinetic adaptations likely facilitated more rapid knee extension and greater jump height during the airborne phase8,40. Compared with previous studies using plyometric training types such as tuck jumps44,45 or drop landings46, which showed limited improvement in jump height, our program produced notable gains, suggesting that targeted hop jump exercises may provide superior enhancement of both force generation and energy transfer efficiency from the AP to vertical direction1,10,47. Time series analysis revealed that differences in extension moment, vertical joint force, and vertical GRF were most apparent just before maximal knee flexion3,7,8, highlighting the critical role of lower limb kinetics in optimizing jump performance and spike execution41. Overall, these findings demonstrate that the volleyball-specific program not only increased jump height but also improved neuromuscular coordination, emphasizing its practical relevance for performance enhancement.

Landing performance – kinematic variables

Notable changes were observed for COM in the landing phase. Specifically, the position of the COM was lowered, and there was an increase in the flexion angular velocity of the knee joint. These modifications reduce the impact force exerted on the body48,49. During the landing phase, players perform rapid movements of the knee joint to mitigate the risk of injury upon ground contact. This enables them to distribute the impact force across the body50. Such reductions in knee joint load may help prevent common volleyball-related lower extremity injuries, including patellar tendinopathy, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) strain, and meniscus injuries, which are often associated with high impact and poor shock absorption during landing51,52. The time immediately before the peak vertical GRF following landing represents the point of maximal loading on the knee joint12. Minimizing the impact force involves proper foot placement on the force platform (for GRF evaluation) and increasing the angular velocity of the knee joint from approximately 34% prior to the appearance of the peak vertical GRF12. In this study, after undergoing the specific training program, participants displayed a rapid increase in the angular velocity of the knee joint during landing.

Landing performance – kinetic variables

In this study, biomechanical variables were evaluated to assess the load on the knee joint during landing, significant changes in kinetic variables were observed to decrease in the extension moment of the knee joint and the AP and vertical joint forces. The moment of the knee joint exhibits a strong correlation with the peak vertical GRF, and a decrease in the extension moment of the knee joint, along with a corresponding decrease in vertical GRF, signifies a stable landing with effective shock absorption48. Generally, during landing motions, the eccentric contraction (passive) of the quadriceps, which involves the passive movement of the knee joint, is executed. This presents challenges in withstanding the load exerted on the joint when the body weight is at its highest, particularly during single-leg landing, further increasing the difficulty53. In this study, despite an increase in jump height following training, the extension moment of the knee joint decreased compared to the pre-test. Therefore, it can be inferred that participants could perform active landings with minimal loading without excessive force14,54. In previous studies, the extension moment during soft landing was about 0.36 and 0.68 Nm/(HT \(\times\) BW) lower than that of normal landing and stiff landing, allowing the next movement to be performed faster after the knee flexion to the maximum14. Moreover, close-chain exercises such as lunges and squats can improve the stability of the femur while decreasing the flexion moment of the knee and small activation of the quadriceps during landing due to improved muscle strength55. In addition, the maximum voluntary isometric contraction of the vastus medialis oblique during lunge causes 76% on average, improving the eccentric strength and neuromuscular control of the quadriceps, leading to active movement during landing56,57. Consequently, it is crucial to apply a systematic training program that promotes active movement of the knee joint53. Time series analysis revealed significant reductions in maximal AP force, vertical joint force, and vertical GRF during the landing phase. These reductions suggest that participants were able to better absorb impact forces, likely due to enhanced eccentric control of the quadriceps and improved lower extremity coordination achieved through the specific training program53,55,56. Given that spike motions involve forward-directed jumps, effective attenuation of impact forces allows players to limit excessive anterior joint loading while maintaining stability and enabling rapid transition to subsequent movements41. This indicates that the training program not only improved jump performance but also enhanced landing mechanics, reducing the overall load on the knee joint and potentially lowering the risk of cartilage damage12.

Limitations and future directions

Several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size (n = 16) limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Because spikes were performed only from the left position, the ecological validity of the results may be constrained, as real-game situations involve greater variability. The determination of spike success was based on expert visual assessment, which introduces potential subjectivity and classification bias. Furthermore, as only male players were included, the applicability of these findings to female or less experienced athletes remains uncertain. In addition, the absence of a control group limits the ability to draw causal inferences regarding the effects of the 4-week training program. These limitations underscore the need for future studies with larger and more diverse samples, objective performance measures, and game-like conditions to strengthen the external validity of the results.

Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of a four-week volleyball-specific training program on knee joint kinematics and kinetics during spike movements in adult players. The training led to increased jump height and improved control of the center of mass during both jumping and landing phases. Compared with prior studies using general plyometric exercises, such as tuck jumps or drop landings, which showed limited improvements in jump height or landing mechanics, our targeted hop jump and plyometric exercises demonstrated both enhanced force generation and better temporal coordination of the trunk and lower extremities. During the jumping phase, peak vertical GRF, extension angular velocity, and flexion moment increased, while at landing, extension moment, AP force, and vertical joint forces decreased, indicating a reduction in knee joint load. These findings suggest that the training program not only enhances jumping performance but also contributes to safer landing mechanics. Applying such specialized training can improve performance efficiency and reduce the risk of injury in volleyball players. Future studies should incorporate quantitative measures of attack performance, such as ball speed, and explore long-term injury prevention strategies across various volleyball movements. This will help optimize training programs for athletes of different ages and skill levels, providing both practical and long-term benefits.

Data availability

The dataset supporting this article is available on request to the first corresponding author.

References

Fuchs, P. X. et al. Spike jump biomechanics in male versus female elite volleyball players. J. Sports Sci. 37, 2411–2419 (2019).

Oliveira, L. D. S., Moura, T. B. M. A., Rodacki, A. L. F., Tilp, M. & Okazaki, V. H. A. A systematic review of volleyball spike kinematics: Implications for practice and research. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 15, 239–255 (2020).

Wagner, H., Tilp, M., Von Duvillard, S. & Mueller, E. Kinematic analysis of volleyball spike jump. Int. J. Sports Med. 30, 760–765 (2009).

Coutts, K. D. Kinetic differences of two volleyball jumping techniques. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 14, 57–59 (1982).

Ikeda, Y., Sasaki, Y. & Hamano, R. Factors influencing spike jump height in female college volleyball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 32, 267–273 (2018).

Ziv, G. & Lidor, R. Vertical jump in female and male volleyball players: a review of observational and experimental studies. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 20, 556–567 (2010).

Fuchs, P. X. et al. Movement characteristics of volleyball spike jump performance in females. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 22, 833–837 (2019).

Pérez-Castilla, A., Jiménez-Reyes, P., Haff, G.G., & García-Ramos, A., Assessment of the loaded squat jump and countermovement jump exercises with a linear velocity transducer: which velocity variable provides the highest reliability?. Sports Biomech. (2021).

Serrien, B., Ooijen, J., Goossens, M. & Baeyens, J.-P. A motion analysis in the volleyball spike—Part 1: Three dimensional kinematics and performance. Int. J. Hum. Mov. Sports Sci. 4, 70–82 (2016).

Briner, W. W. Jr. & Benjamin, H. J. Volleyball injuries: managing acute and overuse disorders. Phys. Sportsmed. 27, 48–60 (1999).

Lobietti, R., Coleman, S., Pizzichillo, E. & Merni, F. Landing techniques in volleyball. J. Sports Sci. 28, 1469–1476 (2010).

Xu, D., Jiang, X., Cen, X., Baker, J. S. & Gu, Y. Single-leg landings following a volleyball spike may increase the risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury more than landing on both-legs. Appl. Sci. 11, 130 (2020).

Loes, M. D., Dahlstedt, L. J. & Thomée, R. A 7-year study on risks and costs of knee injuries in male and female youth participants in 12 sports. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 10, 90–97 (2000).

Zhang, S.-N., Bates, B. T. & Dufek, J. S. Contributions of lower extremity joints to energy dissipation during landings. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 32, 812–819 (2000).

Leporace, G. et al. Influence of a preventive training program on lower limb kinematics and vertical jump height of male volleyball athletes. Phys. Ther. Sport 14, 35–43 (2013).

Zarei, M., Soltani, Z. & Hosseinzadeh, M. Effect of a proprioceptive balance board training program on functional and neuromotor performance in volleyball players predisposed to musculoskeletal injuries. Sport Sci. Health 18, 975–982 (2022).

Freyssin, C. et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in chronic heart failure: effect of an 8-week, high-intensity interval training versus continuous training. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 93, 1359–1364 (2012).

Backx, F. J., Beijer, H. J., Bol, E. & Erich, W. B. Injuries in high-risk persons and high-risk sports: a longitudinal study of 1818 school children. Am. J. Sports Med. 19, 124–130 (1991).

Koshino, Y. et al. Kinematics and muscle activities of the lower limb during a side-cutting task in subjects with chronic ankle instability. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 24, 1071–1080 (2016).

Berriel, G. P. et al. Does complex training enhance vertical jump performance and muscle power in elite male volleyball players?. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 17, 586–593 (2022).

Tseng, K. W. et al. Post-activation performance enhancement after a bout of accentuated eccentric loading in collegiate male volleyball players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 13110 (2021).

Chijimatsu, M. et al. Landing instructions focused on pelvic and trunk lateral tilt decrease the knee abduction moment during a single-leg drop vertical jump. Phys. Ther. Sport 46, 226–233 (2020).

Grgantov, Z., Jelaska, I. & Šuker, D. Intra and interzone differences of attack and counterattack efficiency in elite male volleyball. J. Hum. Kinet. 65, 205 (2018).

Chen, P.-C. et al. Comparative effectiveness of different nonsurgical treatments for patellar tendinopathy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 35, 3117–3131 (2019).

Marotta, N. et al. Late activation of the vastus medialis in determining the risk of anterior cruciate ligament injury in soccer players. J. Sport Rehabil. 29, 952–955 (2019).

Ueno, R. et al. Knee abduction moment is predicted by lower gluteus medius force and larger vertical and lateral ground reaction forces during drop vertical jump in female athletes. J. Biomech. 103, 109669 (2020).

Abián-Vicén, J., Martínez, F., Jiménez, F. & Abián, P. Effects of eccentric single-leg decline squat training performed with different execution times on maximal strength and muscle contraction properties of the knee extensor muscles. J. Strength Cond. Res. 36, 3040–3047 (2022).

Al Attar, W. S. A., Soomro, N., Sinclair, P. J., Pappas, E. & Sanders, R. H. Effect of injury prevention programs that include the Nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injury rates in soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 47, 907–916 (2017).

Cohen, S. B., Whiting, W. C. & McLaine, A. J. Implementation of balance training in a gymnast’s conditioning program. Strength Cond. J. 24, 60–67 (2002).

Comfort, P., Jones, P. A., Smith, L. C. & Herrington, L. Joint kinetics and kinematics during common lower limb rehabilitation exercises. J. Athl. Train 50, 1011–1018 (2015).

Huxel Bliven, K. C. & Anderson, B. E. Core stability training for injury prevention. Sports health. 5, 514–522 (2013).

Kubo, K. et al. Effects of plyometric and weight training on muscle-tendon complex and jump performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 39, 1801–1810 (2007).

Kernozek, T. W. & Ragan, R. J. Estimation of anterior cruciate ligament tension from inverse dynamics data and electromyography in females during drop landing. Clin. Biomech. 23, 1279–1286 (2008).

Mclean, S. G. et al. Impact of fatigue on gender-based high-risk landing strategies. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 39, 502–514 (2007).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39, 175–191 (2007).

Robinson, M. A., Vanrenterghem, J. & Pataky, T. C. Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) for alpha-based statistical analyses of multi-muscle EMG time-series. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 25, 14–19 (2015).

Sole, G., Pataky, T., Tengman, E. & Häger, C. Analysis of three-dimensional knee kinematics during stair descent two decades post-ACL rupture–data revisited using statistical parametric mapping. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 32, 44–50 (2017).

Beerse, M., Larsen, K., Alam, T., Talboy, A. & Wu, J. Joint kinematics and SPM analysis of gait in children with and without Down syndrome. Hum. Mov. Sci. 95, 103213 (2024).

Fukuchi, C. A., Fukuchi, R. K. & Duarte, M. Effects of walking speed on gait biomechanics in healthy participants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 8, 153 (2019).

Sarvestan, J., Kovacikova, Z., Svoboda, Z. & Needle, A. Ankle Kinesio taping impacts on lower limbs biomechanics during countermovement jump among collegiate athletes with chronic ankle instability. Gait. Posture 81, 327–378 (2020).

Mercado-Palomino, E., Aragón-Royón, F., Richards, J., Benítez, J. M. & Ureña Espa, A. The influence of limb role, direction of movement and limb dominance on movement strategies during block jump-landings in volleyball. Sci. Rep. 11, 23668 (2021).

Farley, C. T. & Morgenroth, D. C. Leg stiffness primarily depends on ankle stiffness during human hopping. J Biomech. 32, 267–273 (1999).

Bergmann, J., Kramer, A. & Gruber, M. Repetitive hops induce postactivation potentiation in triceps surae as well as an increase in the jump height of subsequent maximal drop jumps. PLoS ONE 8, e77705 (2013).

Margaritopoulos, S. et al. The effect of plyometric exercises on repeated strength and power performance in elite karate athletes. J. Phys. Educ. 15, 310 (2015).

Tsolakis, C., Bogdanis, G. C., Nikolaou, A. & Zacharogiannis, E. Influence of type of muscle contraction and gender on postactivation potentiation of upper and lower limb explosive performance in elite fencers. Sports Sci. Med. 10, 577 (2011).

Hilfiker, R., Hübner, K., Lorenz, T. & Marti, B. Effects of drop jumps added to the warm-up of elite sport athletes with a high capacity for explosive force development. J. Strength Cond. Res. 21, 550–555 (2007).

Foqhaa, B., Brini, S., Alhaq, I. A., Nairat, Q. & Abderrahman, A. B. Eight weeks plyometric training program effects on lower limbs power and spike jump performances in university female volleyball players. Swedish J. Sci. Res. 8, 1–7 (2021).

Yu, B., Lin, C.-F. & Garrett, W. E. Lower extremity biomechanics during the landing of a stop-jump task. Clin. Biomech. 21, 297–305 (2006).

Sheppard, J. M. et al. Relative importance of strength, power, and anthropometric measures to jump performance of elite volleyball players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 22, 758–765 (2008).

Decker, M. J., Torry, M. R., Wyland, D. J., Sterett, W. I. & Steadman, J. R. Gender differences in lower extremity kinematics, kinetics and energy absorption during landing. Clin. Biomech. 18, 662–669 (2003).

Bisseling, R. W., Hof, A. L., Bredeweg, S. W., Zwerver, J. & Mulder, T. Relationship between landing strategy and patellar tendinopathy in volleyball. Br. J. Sports Med. 41, e8–e8 (2007).

Slovák, L. et al. Response of knee joint biomechanics to landing under internal and external focus of attention in female volleyball players. Mot. Control 28, 341–361 (2024).

Skinner, N. E., Zelik, K. E. & Kuo, A. D. Subjective valuation of cushioning in a human drop landing task as quantified by trade-offs in mechanical work. J. Biomech. 48, 1887–1892 (2015).

Devita, P. & Skelly, W. A. Effect of landing stiffness on joint kinetics and energetics in the lower extremity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 24, 108–115 (1992).

Lawrence, R. K. III., Kernozek, T. W., Miller, E. J., Torry, M. R. & Reuteman, P. Influences of hip external rotation strength on knee mechanics during single-leg drop landings in females. Clin. Biomech. 23, 806–813 (2008).

Ekstrom, R. A., Donatelli, R. A. & Carp, K. C. Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during 9 rehabilitation exercises. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 37, 754–762 (2007).

Pfile, K. R. et al. Different exercise training interventions and drop-landing biomechanics in high school female athletes. J. Athl. Train 48, 450–462 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K., J.M. designed the study. S.K. and D.K. performed the experiment and wrote the main manuscript text. B.Y. analyzed data. D.K., J.M. and S.K. guided the experiment and thesis writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Koo, D. & Moon, J. Biomechanical improvements in performance and injury prevention in volleyball spikes: effects of a 4-week training program. Sci Rep 16, 1841 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31538-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31538-5