Abstract

Nowadays, there is an unmet need for reliable and minimally-invasive diagnosis tools capable of detecting Alzheimer’s disease at early stages. Such tools could significantly reduce the reliance on confirmatory tests that are invasive and costly, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers and neuroimaging. The aim of this study is to validate previously developed diagnosis tools (multivariate models and plasma p-Tau217 levels) in three independents cohorts. For this, a cohort was obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) including some variables (age, Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype, plasma p-Tau217, CSF biomarkers) (n = 113); and two cohorts from cognitive disorders units (Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe (HUiPLaFe, n = 163), Hospital Doctor Peset (n = 31)), whose plasma samples were analysed to determine plasma p-Tau217, and to evaluate the previous diagnosis tools performance. For the cohort from HUiPLaFe, the multivariate model (plasma p-Tau217, age, ApoE genotype) showed a sensitivity of 94.9% and a specificity of 88.2%; for the cohort from Hospital Doctor Peset, the sensitivity was 100% and specificity 80%; for the ADNI cohort, sensitivity was 89.5% and specificity 39.5%. Regarding the plasma p-Tau217 levels, the results were satisfactory for the cognitive disorders units; while ADNI cohort showed very low specificity. In conclusion, the multivariate model was clinically validated in independent cohorts from clinical units, representing its first step for implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the main cause of dementia worldwide, characterized by a progressive cognitive impairment. AD physiopathology is primarily defined by extracellular deposition of amyloid β (Aβ), and the intracellular hyperphosphorylation of Tau in the brain1. Currently, AD diagnosis is based on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers2 or amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging3. However, these are invasive and costly techniques that are not suitable for use in the general practice. Furthermore, the recent approvals of disease-modifying treatments (lecanemab, donanemab)4, strengthens the need for early, accurate and accessible diagnostic methods.

Recent studies have focused on the identification of plasma biomarkers5,6. Among them, plasma p-Tau217 has been postulated as the most promising candidate for diagnostic purposes7,8. However, there is still a need for clinical validation of these plasma biomarkers in order to develop a reliable, early and specific AD diagnosis method, which could be implemented in the clinical practice. Other recent works have investigated the measurement of Aβ42, Aβ40, total-Tau (t-Tau), other phosphorylated tau isoforms (p-Tau181, p-Tau231), neurofilament light (NfL) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)9,10. The determination of these biomarkers requires highly sensitivity techniques (e.g. mass spectrometry, Single Molecule Array (SIMOA®), digital PCR) due to their low concentrations in plasma samples11,12,13. In fact, SIMOA offers a sensitivity approximately 1000 times greater than that of conventional ELISA, while using very low sample volumes10,14,15. However, these analytical methods are complex, time-consuming, non-automated, and require highly trained personnel. Therefore, their implementation in clinical settings remains challenging16,17. Recently, a few studies employing automated techniques have been reported in literature. In fact, Feizpour’s et al. used the Lumipulse® platform to measure plasma p-Tau217 levels, demonstrating strong discriminative capacity between Aβ PET-positive and Aβ PET-negative individuals18. Similarly, a predictive model combining plasma p-Tau217 with other predictors (age, Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) genotype) was developed, yielding promising results through a double cut-off approach19. Furthermore, Quaresima’s et al. utilized the Lumipulse® technique to assess biomarkers in both plasma and CSF (p-Tau, Aβ42, Aβ40), showing promising results with high validity, low intra-day variability, and similar accuracy compared to SIMOA20. In addition, Martínez-Dubarbie’s et al. used this technique to measure CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, p-Tau181 and t-Tau, as well as plasma levels of Aβ40, Aβ42, p-Tau217, and p-Tau181, demonstrating excellent performance in identifying AD-related pathological changes21.

A crucial step for the implementation of plasma biomarkers for AD diagnosis is their clinical validation in independent cohorts. In literature, only a few studies have employed external cohorts (e.g. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), BioFINDER, European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia (EPAD)) to validate potential biomarkers or diagnosis models22,23,24. In fact, Brum et al. used a validation cohort from BioFinder (n = 212 patients), which included some data (Aβ-PET, ApoE genotype, sex, age, Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, CSF Aβ42/Aβ40, plasma p-Tau 217 levels)25. Similarly, Li et al. used a validation cohort from ADNI (n = 353 cognitively normal controls) incorporating demographic data, ApoE genotype and neuropsychological tests results26. These validation studies showed that minimally-invasive biomarkers, along with automated and cost-effective techniques, can yield robust and promising diagnosis results for AD, and potentially reducing the need for lumbar puncture and PET imaging.

The aim of the present study is to clinically validate two AD diagnosis tools, previously developed and based on plasma p-Tau217 levels19, using three independent cohorts, which are from two cognitive disorders units (Hospital Universitari i Politècnic La Fe (HUiPLaFe), Hospital Doctor Peset), and the ADNI cohort. This work represents a relevant first step toward the clinical implementation of the developed diagnosis tools.

Results

Demographic and clinical description of the cohorts

The demographic and clinical data from the HUiPLaFe cohort are summarized in Table S1 (see Supplementary Material). Significant differences were observed between groups for age, ApoE genotype, CSF biomarkers and some neuropsychological scores (Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) sum of boxes, MMSE, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)). Also, statistically significant differences were found for plasma p-Tau217 levels.

The demographic and clinical data from the Hospital Doctor Peset cohort are summarized in Table S2 (see Supplementary Material). Significant differences were detected in age, sex, MMSE, CSF biomarkers, and plasma p-Tau217 levels.

The demographic and clinical data from the ADNI cohort are summarized in Table S3 (see Supplementary Material). Significant differences were observed for CSF biomarkers and plasma p-Tau217 levels.

Validation of the developed multivariate model for AD diagnosis

HUiPLaFe cohort

For the validation of the one cut-off model developed in a previous study19, the probability of developing AD (P(AD)) was calculated from plasma p-Tau217 levels, ApoE genotype and age19. The patients in this cohort were considered AD for P(AD) > 0.5 (n = 96), and non- AD for P(AD) ≤ 0.5 AD (n = 67). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 1). In Fig. 1 it is represented the Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve that was obtained.

For the validation of the two cut-offs model previously developed19, the probability of developing AD was calculated for these patients. They were considered AD for P(AD) > 0.57 (n = 78), non-AD for P(AD) < 0.41 (n = 34), and uncertain for P(AD) between 0.41 and 0.57 (n = 51). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 1). The performance of this model was satisfactory, and it was improved in comparison with the one-cut-off model. However, the uncertain cases represent the 31% of total cases; among them 27 patients were AD and 24 patients were non-AD, according to CSF biomarkers. Figure 2a shows the different probability of developing AD from the double cut-off model between AD and non-AD patients identified from CSF biomarkers. As can be seen, 70.5% of the AD patients were above the high cut-off, while 51.7% of the non-AD patients were below the low cut-off.

Hospital doctor peset cohort

For the validation of the one cut-off multivariate model20, the probability of developing AD was calculated for these patients. They were considered AD for P(AD) > 0.5 (n = 22), and non-AD for P(AD) ≤ 0.5 (n = 9). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 1). The ROC curve can be seen in Fig. 1.

For the validation of the two cut-offs model19, the probability of AD was calculated for these patients. They were considered AD for P(AD) > 0.57 (n = 19), non-AD for P(AD) < 0.41 (n = 4), and uncertain for P(AD) between 0.41 and 0.57 (n = 8). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 1). The performance of the model improved for this two-cut-off approach. However, the uncertain cases represented the 26% of total cases; among them 4 patients were AD and 4 were non-AD, according to CSF biomarkers. Figure 2b shows the different probability of developing AD from the double cut-off model between AD and non-AD patients identified from CSF biomarkers. As can be seen, 81.8% of the AD patients were above the high cut-off, while only 44.4% of non-AD patients were below the low cut-off.

In both approaches (one cut-off, two cut-offs), this cohort performance showed wide confidence intervals (CI), especially for specificity (56.5–98.0% and 37.6–96.4%), reflecting considerable uncertainty.

ADNI cohort

For the validation of the one cut-off model previously developed19, the probability of developing AD was calculated for these patients. They were considered AD for P(AD) > 0.5 (n = 43), and non-AD for P(AD) ≤ 0.5 (n = 70). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 1). The performance of the model in this cohort was lower compared to the previous cohorts from cognitive disorders units. The ROC curve can be seen in Fig. 1.

For the validation of the two cut-offs model previously developed19, the probability of developing AD was calculated for these patients. They were considered AD for P(AD) > 0.57 (n = 24), non-AD for P(AD) < 0.41 (n = 33), and uncertain for P(AD) between 0.41 and 0.57 (n = 56). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 1). In general, the performance of this two-cut-off approach was better than that from the one-cut-off model. However, the uncertain cases represented the 49% of total cases; among them, 24 patients were classified as AD and 32 as non-AD, according to CSF biomarkers. Figure 2c shows the different probability of developing AD from the double cut-off model. As can be seen, 70.8% of the AD patients were above the high cut-off, while only 23.1% of non-AD patients were below the low cut-off.

Validation of the plasma p-Tau217 levels for AD diagnosis

HUiPLaFe cohort

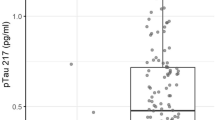

For the validation of the two-cut-offs (0.12–0.29 pg ml− 1) previously established for plasma p-Tau21719, the plasma levels of patients from HUiPLaFe cohort were evaluated. They were between 0.0075 and 4.12 pg mL− 1, and the patients were classified as AD if p-Tau 217 levels were > 0.29 pg ml− 1 (n = 84), non-AD if p-Tau 217 levels were < 0.12 pg ml− 1 (n = 34), and uncertain if p-Tau 217 levels were between 0.12 and 0.29 pg ml− 1 (n = 45). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 2). The performance of this approach was similar to that from the two-cut-off model approach. The uncertain cases represented the 28% of total cases; among them 19 patients were AD and 26 non-AD, according to CSF biomarkers.

Hospital doctor peset cohort

For the validation of the double cut-off previously established for plasma p-Tau21719, these levels were determined for these patients. They were between 0.085 and 1.494 pg mL− 1, and the patients were classified as AD (n = 21), non-AD (n = 6), and uncertain (n = 4). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 2), observing satisfactory performance metrics, but wide CI for specificity (56.5–100.0%) and NPV (43.6–97.0%) The uncertain cases represented the 13% of total cases; and all of them were classified as non-AD according to CSF biomarkers.

ADNI cohort

For the validation of the double cut-off previously established for plasma p-Tau21719, the plasma p-Tau217 levels for these patients in ADNI database were harmonized, and the corresponding values were between 0.002 and 2.9 pg mL− 1. So, these patients were classified as AD (n = 1), non-AD (n = 74), and uncertain (n = 38). Comparing these results with the reference classification based on CSF biomarkers, the diagnosis indexes were calculated (see Table 2). The performance of this approach in this cohort was lower than in the other cohorts, as well as lower than that of the two-cut-off model. The uncertain cases represented the 34% of total cases; among them, 23 patients were classified as AD, and 15 as non-AD, according to CSF biomarkers.

Comparison of diagnosis tools

Figure 3 shows the AD risk stratification for double cut-off model and double cut-off p-Tau217 levels in each validation cohort. As can be seen, similar results were obtained from each cohort, but the double cut-off multivariate model provided slightly lower risk than p-Tau217 levels for HUiPLaFe and Hospital Doctor Peset cohorts. Approximately 50% of the HUiPLaFe and ADNI patients, and more than 60% of Hospital Doctor Peset cohort showed high probability of developing AD, determined from the double cut-off model (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Currently, the identification of biomarkers that are easy to interpret and widely accessible is essential for advancing primary care and enabling early detection of AD. In line with this objective, several plasma biomarkers have been investigated27,28, with plasma p-Tau217 emerging as a particularly promising candidate. These advancements are expected to significantly contribute to the development of novel AD treatments in the near future.

This study focuses on the clinical validation of a plasma-based diagnostic model across independent cohorts. Initially developed using data from a cognitive disorders unit (HUiPLaFE, patients recruited between 2020 and 2023)19, the model represents a promising clinical application. The preliminary model evaluated the ability of plasma p-Tau217, ApoE genotype and age to distinguish between AD and non-AD patients, as confirmed by CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio. Using two approaches (one cut-off, two cut-offs), the model was validated in three independent cohorts (HUiPLaFe, Hospital Doctor Peset, ADNI).

Regarding plasma analysis, Martínez-Dubarbie et al. used the fully-automated Lumipulse® technique to measure plasma p-Tau217, showing promising results as a preclinical AD biomarker29. In addition, Giuffrè’s et al. employed Lumipulse® technology to differentiate between Aβ-negative amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI) patients and those with aMCI within the AD continuum, measuring Aβ40, Aβ42 and p-Tau181. They found an association with CSF biomarkers (area under the curve (AUC) 0.895, sensitivity 95.1%, specificity 82.8%), demonstrating that Lumipulse® is a useful assay to distinguish between aMCI due to AD and aMCI unlikely to be caused by AD30. Also, Arranz et al. used Lumipulse® technology to measure plasma p-Tau181, p-Tau217, Aβ42 and Aβ40. Using linear regression, they compared amyloid-positive (A+) and amyloid-negative (A-) groups (based on CSF biomarkers) with these plasma markers. As a result, they observed that plasma p-Tau217 had the highest ability to discriminate between A + and A- individuals, suggesting that this technique has promising accuracy for detecting AD patients. However, different cut-offs values were obtained across the various centres31. The generalizability of diagnosis cut-offs remains a major challenge, as several studies often report different thresholds across cohorts5. These discrepancies are largely driven by heterogeneity in assay platforms, participant selection criteria, and analytical variables32. Therefore, there is an increasing need to harmonize or re-estimate cut-offs specifically for each cohort, or to carry out cohort-specific adjustments to ensure diagnosis accuracy and a broader implementation5. In the present study, the poor performance observed in the ADNI cohort, could be due to the use of a different analytical platform for measuring plasma p-Tau217. To address this, ADNI values were harmonized with those from the HUiPLaFe cohort (reference) through a location-scale transformation, which improved ADNI performance (AUC 0.727, sensitivity 79%, specificity 48%) and contributed to the external validation of diagnostic thresholds. These findings underscore the need for either cohort-specific cut-offs or harmonization strategies to ensure broader applicability of plasma biomarkers in clinical and research settings.

Regarding the validation of diagnosis models, a previous study evaluated plasma p-Tau217, age and ApoE genotype as relevant variables for AD diagnosis, achieving high discriminatory performance (AUC 0.943)25, similarly to the previously developed model19, which is under validation in the present study. Other works using external validation cohorts, composed by patients clinically diagnosed (AD, MCI, cognitively normal controls), assessed a two-cut-off approach on plasma p-Tau181 levels and changes in cognitive test scores (MMSE score), obtaining an AUC of 0.9332; also, a satisfactory AUC (0.850) was reported29; as well as plasma p-Tau217 data (using mass spectrometry and immunoassay) provided results similar to those observed in their internal cohort24.

The present study shows some limitations, the HUiPLaFe cohort (recruited between 2024 and 2025) is not strictly independent, as the approaches under validation were previously developed using data from other patients (recruited between 2020 and 2023) in the same cognitive disorders unit. Therefore, it could be considered a temporal validation. Additionally, the small sample size may affect the generalizability and statistical power of the findings. In this sense, results from the Hospital Doctor Peset cohort reflect considerable uncertainty, and thus these promising results should be considered preliminary. Finally, plasma p-Tau217 levels in the ADNI cohort were measured using a different assay technique, hampering the application of the cut-offs obtained in the previous study from Lumipulse® technology; so, some harmonization efforts were carried out to solve these assay differences. In addition, ADNI patients were classified (AD, non-AD) using different CSF criteria, since the CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 was not available for them. It is important to note that the strongest validation results were observed in the HUiPLaFe cohort, where the diagnosis tools were initially calibrated. While these findings support the robustness of the tools under validation conditions, they also highlight the need for further external validation across independent cohorts and laboratory settings. Such validation is essential to confirm the generalizability and clinical utility of the proposed diagnosis tools beyond the original development context.

To conclude, previously developed diagnosis tools based on plasma p-Tau217 levels were validated across three independent cohorts. The diagnosis performance of the double cut-off p-Tau217 model was satisfactory in cohorts from cognitive disorder units, with sensitivity ranging from 94 to 96% and specificity from 91 to 100%. However, performance was lower in the ADNI cohort (sensitivity 82%, specificity 45%), likely due to differences in comparison with the reference HUiPLaFe cohort (plasma p-Tau217 analytical assay, patients’ classification criteria) in spite of the harmonization of these levels. The diagnosis performance of the multivariate double cut-off model (including plasma p-Tau217, age, ApoE genotype), was satisfactory across all three validation cohorts (sensitivity 89–100%), suggesting its potential utility as a screening tool for early and specific detection of AD. This validated strategy could reduce the need for lumbar punctures, offering significant benefits to both patients and healthcare systems. Overall, these findings support the clinical implementation of a minimally invasive and specific approach for AD screening in general population.

The present study shows attributes that make it suitable for primary screening purposes, where high sensitivity is prioritized to minimize false negatives, and moderate specificity is acceptable given that positive cases would undergo confirmatory testing. In a screening context, the test could be useful to identify individuals who need further clinical evaluation, thereby reducing the burden on more resource-intensive confirmatory diagnostics. Future research and optimization efforts will focus on enhancing specificity to potentially expand its applicability to diagnosis.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study carried out in the Cognitive Disorder Unit from the Neurology Service at the HUiPLaFe (Valencia, Spain). Patients from different cohorts were included in this study.

First, patients from the HUiPLaFe cohort were evaluated33. They were recruited from 2024 to 2025 in the Cognitive Disorder Unit of HUiPLaFe. They were between 50 and 80 years old (n = 163). Their diagnosis was based on the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) criteria. In fact, different CSF biomarkers were determined (Aβ42, Aβ40, p-Tau181, t-Tau, NfL)34. Specifically, the AD (n = 105) vs. non-AD (n = 58) classification was carried out attending to CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 levels (< 0.069 pg mL− 1 for AD). The cognitive status was characterized by neuropsychological evaluation (CDR, composed by a scale of global score and the sum of boxes; MMSE; RBANS and its domains Visuospatial/Constructional (V/C), Language (L), Attention (A), Immediate Memory (IM), and Delayed Memory (DM); Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ); Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL); Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)). According to the neuropsychological performance, the patients were classified as cognitively unimpaired (CU), MCI and mild dementia. In the AD subgroup, 6.9% patients were CU, 82.3% were MCI and 10.8% were mild dementia. On the other hand, the non-AD patients were 16.3% CU, 75.5% MCI and 6.1% mild dementia.

Second, a cohort of patients from the Neurology Unit Hospital Doctor Peset (Valencia, Spain) (n = 31) was evaluated. These patients were classified into AD (n = 22) and non-AD (n = 9) according to the CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 levels. According to the neuropsychological performance, in the AD group 9.1% of patients were classified MCI, and 90.9% as mild dementia; while in the non-AD group, 11.1% of patients were classified as CU, 33.3% as MCI and 55.6% as mild dementia.

Third, a cohort was obtained from ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu), including different variables (age, ApoE genotype, plasma p-Tau217, CSF Aβ42, CSF p-Tau181, CSF t-Tau, research group). In the present study, these patients were classified into AD (n = 48) and non-AD (n = 65) groups according to the CSF Aβ42 (< 880 pg mL− 1), CSF t-Tau/Aβ42 (> 0.3)35 or CSF p-Tau181/Aβ42 (> 0.025) levels36, at least two of these biomarkers were impaired for AD patients. According to the neuropsychological performance, in the AD group 25.0% of patients were classified as CU, 52.1% as MCI and 22.9% as mild dementia; while in non-AD group, 35.4% were classified as CU, 49.2% as MCI and 15.4% as mild dementia.

Data used were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and it was approved by the Ethics Committee (CEIC) from Health Research Institute La Fe (Valencia, Spain) (reference number: 2022-990-1; date: 8 February 2023). All participants signed informed consent prior to their recruitment.

Blood samples collection and analysis

Blood samples were obtained from HUiPLaFe and Hospital Doctor Peset patients. For this, it was used a tube containing EDTA. Then, these samples were centrifuged (1160 ց, 15 min, 25 °C), to separate the plasma fraction into a new tube. The plasma samples were stored at -80 °C until analysis.

For the analysis, plasma samples were thawed on ice and centrifuged. After that, plasma p-Tau217 level was determined by means of Lumipulse® technology (G600II automated platform, Fujirebio Diagnostics, Malvern, USA), following the manufacturer recommendations. For the ADNI cohort, plasma p-Tau217 levels were provided using Janssen plasma p217 + tau Simoa® assay.

The genotyping of ApoE was determined using LightMix® Kit ApoE C112R R158C from Roche Diagnostics (https://www.roche-as.es/lightmix_global, accessed on 8 May 2025) and following the manufacturer protocol. All patients provided a specific informed consent for ApoE genotype.

Statistical analysis

In the statistical analysis, numerical variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR), and the Mann Whitney test was used to analyse differences between groups; categorical variables were expressed as the number and percentage, and the Pearson’s Chi-Square test was used to analyse differences in the frequency distribution between groups.

The diagnosis tools (one cut-off diagnosis model, double cut-off diagnosis model, double cut-off plasma p-Tau217) previously developed from patients recruited between 2020 and 2023 in HUiPLaFe19, were validated in different assessed cohorts (HUiPLaFe (patients recruited between 2024 and 2025), Hospital Doctor Peset, ADNI). First, ROC analysis was carried out to calculate the AUC of the model, along with sensitivity, specificity, and positive/negative predictive values (PPV, NPV) at pre-specified cut-offs (95% Sensitivity, 95% Specificity), using the AD/non-AD classification from CSF Aβ42/Aβ40 level as reference. The one-cut-off model approach classified participants as AD or non-AD based on the P(AD) of 0.5. The double cut-off model approach, classified participants as AD (P(AD) > 0.57), uncertain (0.41 ≥ P(AD) ≥ 0.57), or non-AD (P(AD) < 0.41). The double cut-off plasma p-Tau217 levels classified participants as AD (> 0.29 pg mL− 1), non-AD (< 0.12 pg mL− 1) and uncertain (0.12–0.29 pg mL− 1).

The ADNI plasma p-Tau217 values obtained from a different analytical technique were normalized to harmonize them with the concentrations measured in HUiPLaFe (reference cohort). For this, a location-scale transformation based on log-transformed values was carried out. First, all the p-Tau217 levels (ADNI, HUiPLaFe) were transformed using the natural logarithm of (x + 1) to reduce right-skewness. Second, the values from ADNI cohort were standardized (z-score) using their mean and standard deviation in the log scale. Third, the ADNI values were rescaled using the mean and standard deviation of the reference cohort (HUiPLaFe). Finally, the rescaled values were back-transformed to the original scale using the inverse log transformation (expm1), resulting in p-Tau217 distribution aligned with the reference cohort, while preserving the internal ranking of subjects.

The diagnosis indexes were reported with 95% CI. Statistical significance was defined as p value < 0.05. All these statistical analyses were carried out by SPSS v23 software (Chicago, U.S.A), R software (version 4.2.3.), and the packages cutpoint (version 1.1.2) and ggplot2 (version 3.5.1).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Beder, N., Belkhelfa, M. & Leklou, H. Involvement of inflammasomes in the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 102 (1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/13872877241283677 (2024).

Blennow, K. & Zetterberg, H. Biomarkers for alzheimer’s disease: current status and prospects for the future. J. Intern. Med. 284 (6), 643–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12816 (2018).

Patil, S. et al. Clinical applications of PET imaging in alzheimer’s disease. PET. Clin. 20 (1), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpet.2024.09.015 (2025).

Thawabteh, A. M. et al. Recent advances in therapeutics for the treatment of alzheimer’s disease. Molecules 29 (21), 5131. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29215131 (2024).

Hansson, O., Blennow, K., Zetterberg, H. & Dage, J. Blood biomarkers for alzheimer’s disease in clinical practice and trials. Nat. Aging. 3 (5), 506–519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00403-3 (2023).

Therriault, J. et al. Diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease using plasma biomarkers adjusted to clinical probability. Nat. Aging. 4 (11), 1529–1537. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00731-y (2024).

Ashton, N. J. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a plasma phosphorylated Tau 217 immunoassay for alzheimer disease pathology. JAMA Neurol. 81 (3), 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.5319 (2024).

Devanarayan, V. et al. Plasma pTau217 predicts continuous brain amyloid levels in preclinical and early alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 20 (8), 5617–5628. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14073 (2024).

Galvin, J. E., Kleiman, M. J., Estes, P. W., Harris, H. M. & Fung, E. Cognivue clarity characterizes mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease in biomarker confirmed cohorts in the Bio-Hermes study. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 24519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75304-5 (2024).

Álvarez-Sánchez, L. et al. New approach to specific Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis based on plasma biomarkers in a cognitive disorder cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. e70034 https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.70034 (2025).

Xu, T. et al. Genetic spectrum features and diagnostic accuracy of four plasma biomarkers in 248 Chinese patients with frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 20 (10), 7281–7295. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14215 (2024).

Yilmaz, S. N. et al. From Organotypic Mouse Brain Slices to Human Alzheimer’s Plasma Biomarkers: A Focus on Nerve Fiber Outgrowth. Biomolecules. 14(10), 1326. Published. Oct 18. (2024). https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14101326 (2024).

Karikari, T. et al. A streamlined, resource-efficient immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry method for quantifying plasma amyloid-β biomarkers in alzheimer’s disease. Res. Sq. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4947448/v1 (2024). rs.3.rs-4947448.

Álvarez-Sánchez, L. et al. Early alzheimer’s disease screening approach using plasma biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (18), 14151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241814151 (2023).

Lotierzo, M., Urbain, V., Dupuy, A. M. & Cristol, J. P. Evaluation of a new automated immunoassay for the quantification of anti-Müllerian hormone. Pract. Lab. Med. 25, e0022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plabm.2021.e00220 (2021).

Kwon, H. S., Yu, H. J. & Koh, S. H. Revolutionizing alzheimer’s diagnosis and management: the dawn of Biomarker-Based precision medicine. Dement. Neurocogn Disord. 23 (4), 188–201. https://doi.org/10.12779/dnd.2024.23.4.188 (2024).

Arslan, B., Zetterberg, H. & Ashton, N. J. Blood-based biomarkers in alzheimer’s disease - moving towards a new era of diagnostics. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 62 (6), 1063–1069. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2023-1434 (2024).

Feizpour, A. et al. Detection and staging of alzheimer’s disease by plasma pTau217 on a high throughput immunoassay platform. EBioMedicine 109, 105405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105405 (2024).

Álvarez-Sánchez, L. et al. Promising clinical tools for specific alzheimer disease diagnosis from plasma pTau217 and ApoE genotype in a cognitive disorder unit. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 16316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01511-3 (2025).

Quaresima, V. et al. Plasma p-tau181 and amyloid markers in alzheimer’s disease: A comparison between lumipulse and SIMOA. Neurobiol. Aging. 143, 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2024.08.007 (2024).

Martínez-Dubarbie, F. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of plasma p-tau217 for detecting pathological cerebrospinal fluid changes in cognitively unimpaired subjects using the lumipulse platform. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 11 (6), 1581–1591. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2024.152 (2024).

Manjavong, M. et al. Performance of plasma biomarkers combined with structural MRI to identify candidate participants for alzheimer’s Disease-Modifying therapy. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 11 (5), 1198–1205. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2024.110 (2024).

Dhana, K. et al. External validation of dementia prediction models in black or African American and white older adults: A longitudinal population-based study in the united States. Alzheimers Dement. 20 (11), 7913–7922. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.14280 (2024).

Warmenhoven, N. et al. A Comprehensive Head-to-Head Comparison of Key Plasma Phosphorylated Tau 217 Biomarker Tests. Preprint. medRxiv; (2024). https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.02.24309629

Brum, W. S. et al. A two-step workflow based on plasma p-tau217 to screen for amyloid β positivity with further confirmatory testing only in uncertain cases. Nat. Aging. 3 (9), 1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-023-00471-5 (2023).

Li, T. R. et al. A prediction model of dementia conversion for mild cognitive impairment by combining plasma pTau181 and structural imaging features. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 30 (9), e70051. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.70051 (2024).

Li, W., Sun, L., Yue, L. & Xiao, S. Diagnostic and predictive power of plasma proteins in alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study in China. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 17557. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66195-7 (2024).

Torres Robledillo, S. et al. Validation of plasma biomarkers in alzheimer disease. Clin. Chim. Acta. 558, 118996 (2024). 1016/j.cca.2024.118996.

Giuffrè, G. M. et al. Performance of fully-automated high-throughput plasma biomarker assays for alzheimer’s disease in amnestic mild cognitive impairment subjects. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 11 (4), 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2024.58 (2024).

Tropea, T. F. et al. Plasma phosphorylated tau181 predicts cognitive and functional decline. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. 10 (1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51695 (2023).

Arranz, J. et al. Diagnostic performance of plasma pTau 217, pTau 181, Aβ 1–42 and Aβ 1–40 in the LUMIPULSE automated platform for the detection of alzheimer disease. Preprint Res. Sq. rs.3.rs-3725688 https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3725688/v1 (2023).

Barthélemy, N. R. et al. Highly accurate blood test for alzheimer’s disease is similar or superior to clinical cerebrospinal fluid tests. Nat. Med. 30 (4), 1085–1095. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02869-z (2024).

Baquero, M. et al. Insights from a 7-Year dementia cohort (VALCODIS): ApoE genotype evaluation. J. Clin. Med. 13 (16), 4735. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164735 (2024).

Jack, C. R. Jr. et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14 (4), 535–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 (2018).

Hansson, O. et al. CSF biomarkers of alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-β PET and predict clinical progression: A study of fully automated immunoassays in biofinder and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimers Dement. 14 (11), 1470–1481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.01.010 (2018).

Leuzy, A. et al. Robustness of CSF Aβ42/40 and Aβ42/P-tau181 measured using fully automated immunoassays to detect AD-related outcomes. Alzheimers Dement. 19 (7), 2994–3004. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12897 (2023).

Acknowledgements

CC-P acknowledges a postdoctoral “Miguel Servet” grant CPII21/00006 and FIS project PI22/00594 from Health Institute Carlos III and co-funded by European Union; and a consolidation project from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Spain) (ref. CNS2022-135327). AM-N and AL acknowledge their grants associated to the FORT23/00021 project from Health Institute Carlos III. CP-B acknowledges a predoctoral “PFIS” grant FI20/00022 from Health Institute Carlos III.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson &Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Funding

Grant CNS2022-135327 funded by MICIU/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. Also, this study has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the project FORT23/00021 of the Fortalece program from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.N.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. L.A.S.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. L.F.G.: Methodology, Investigation. A.L.: Methodology. C.P.B.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. A.B.: Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. N.P.: Methodology. H.V: Methodology. M.B.: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision. C.C.P.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee from Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria La Fe (Valencia, Spain) (Reference number: 2022-990-1).

Informed consent

All participants signed informed consent prior to their recruitment.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martí-Navia, A., Álvarez-Sánchez, L., Ferré-González, L. et al. Clinical validation of new alzheimer disease diagnosis tools based on plasma p-Tau217. Sci Rep 16, 1472 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31613-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31613-x