Abstract

The increasing co-occurrence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) highlights the need for early risk stratification. This study aimed to identify predictive metabolic indicators and determine their optimal cut-off values for predicting MAFLD and abnormal fasting blood glucose (FBG) in a health check-up cohort. This cross-sectional study of 3002 participants assessed the severity of hepatic steatosis (ultrasonographic grade 0–5) in individuals with and without MAFLD and FBG. Metabolic indicators were evaluated for correlation and predictive performance using Spearman’s correlation, multivariate regression, and ROC analysis. FBG levels weakly correlated with the severity of hepatic steatosis (ρ = 0.285, P < 0.001). BMI, TG, SBP, hepatic steatosis severity, and HGB were independent predictors of FBG. For hepatic steatosis severity, BMI (OR range 1.267–1.323) and TG (OR: 1.111–1.222) were consistent risk factors. The optimal cut-offs for predicting MAFLD with elevated FBG were BMI ≥ 24.835 kg/m2 (AUC = 0.906), TG ≥ 1.655 mmol/L (AUC = 0.795), and SBP ≥ 132.5 mmHg (AUC = 0.777) (all P < 0.001). This study suggests that routine metabolic indicators—particularly BMI, TG, and SBP—may be valuable for the early identification and risk stratification of MAFLD and abnormal FBG. We recommend initiating comprehensive metabolic management once key indicators become abnormal to strengthen the integrated prevention of MAFLD and T2DM. These findings provide translatable evidence for advancing early warning systems and precision interventions for both conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) represents a substantial global health burden, currently affecting approximately 39% of the worldwide population1. The evolution of its terminology from “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” to “MAFLD” reflects growing recognition of its fundamental links to systemic metabolic dysfunction, including obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome2,3.The convergence of MAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presents a particular clinical challenge. Recent epidemiological studies indicate that over 70% of T2DM patients have concurrent MAFLD, with prevalence rates continuing to increase annually4. This association extends across the dysglycemic spectrum, including individuals with impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance, positioning MAFLD as a significant comorbidity in diabetes management5. The two conditions maintain a bidirectional relationship: T2DM promotes MAFLD incidence and progression, while MAFLD exacerbates diabetes risk—a vicious cycle primarily driven by underlying insulin resistance6,7.

Clinically, the MAFLD-T2DM synergy substantially elevates the risk of both hepatic and extrahepatic complications. Patients with both conditions experience accelerated liver fibrosis progression toward cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, alongside increased incidence of cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular events, and chronic kidney disease8,9,10. Consequently, early detection and intervention in co-affected individuals may yield significant benefits for preventing these serious outcomes11,12.The central role of metabolic dysregulation in MAFLD pathogenesis is well-established13. A predictive model for MAFLD development in patients with T2DM has demonstrated that its presence is associated with more severe metabolic disturbances, including exacerbated dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertension14. Sex-specific associations have also been observed, with uric acid (UA) as an independent MAFLD predictor in males with newly diagnosed T2DM, while in females, this association was significant only in non-overweight/obese individuals15. Despite these advances, current evidence regarding comprehensive metabolic predictors for the progression of hepatic steatosis in MAFLD and its relationship with glucose metabolic alterations remains incomplete. The potential of routine metabolic indicators for risk stratification in general populations requires further validation.

To address these knowledge gaps, this cross-sectional study systematically investigates the associations between the severity of hepatic steatosis and multiple glycolipid metabolic indicators in a large health screening cohort. We further aim to evaluate their predictive performance and establish optimal clinical cut-off values. Our results are expected to provide valuable evidence for early identification of high-risk individuals and inform the development of precision intervention strategies for MAFLD and T2DM comorbidity.

Study population and methods

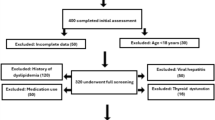

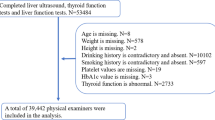

Study population

The study population was selected from group health examinees at the Preventive Treatment Center of the Affiliated Hospital of Changchun University of Chinese Medicine between May and October 2024. Individuals who concurrently underwent fasting blood glucose (FBG) testing and hepatic color Doppler ultrasound examinations were included, resulting in a final cohort of 3002 participants.

Methods

Baseline characteristics

Trained healthcare professionals collected baseline characteristics from all participants, including sex, age, height, body weight, and blood pressure (BP). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters (kg/m2). All anthropometric and blood pressure measurements were obtained under standardized environmental conditions to ensure consistency.

Collection of multimetabolic indicators

Venous blood samples were collected from participants after an overnight fast. The analysis of these samples, performed by clinical laboratory technicians, measured FBG, triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), UA, urine creatinine (UCr), hemoglobin (HGB), and red blood cell (RBC) count, using standardized commercial assay kits.

Color Doppler ultrasonography examination

Hepatic steatosis and its severity were assessed by certified sonographers using hepatic color Doppler ultrasonography.For the purpose of statistical analysis, the severity of hepatic steatosis was graded according to the following six-tiered system based on ultrasonographic findings:

-

Grade 0: No ultrasonographic evidence of fatty liver, including the absence of non-uniform fatty liver patterns.

-

Grade 1: Mild non-uniform fatty liver.

-

Grade 2: Mild to moderate non-uniform fatty liver.

-

Grade 3: Moderate non-uniform fatty liver.

-

Grade 4: Moderate to severe non-uniform fatty liver.

-

Grade 5: Severe non-uniform fatty liver.

This six-tiered system was developed for the present study to provide a more granular assessment of steatosis severity. The diagnosis of MAFLD was made in accordance with international consensus criteria, which require the presence of hepatic steatosis in addition to one of the following three criteria: overweight or obesity (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 for Asian populations), presence of T2DM, or evidence of metabolic dysregulation. This grading system was uniformly applied for all subsequent statistical analyses. It is important to note that for participants diagnosed with MAFLD, this grade specifically refers to the severity of the underlying hepatic steatosis.

Statistical methods

Data management was performed using Microsoft Excel, and statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 26.0 and R 4.4.3. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P < 0.05. Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Group comparisons for non-normally distributed variables were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test, with post-hoc pairwise comparisons conducted using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni correction. Associations between variables were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis.Multiple linear regression was employed to identify independent factors influencing FBG levels, with model assumptions verified using Durbin-Watson statistics (approximating 2) and variance inflation factors (VIF < 10). A generalized ordered logistic regression model was applied to evaluate factors associated with hepatic steatosis severity. Binary logistic regression was used to screen for significant predictive variables.Predictive performance was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, with the area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence interval (CI) used to quantify discriminative ability. The optimal cutoff value for each indicator was determined by maximizing Youden’s index.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study included a total of 3,002 participants, comprising 2,712 males (mean age 48.45 ± 0.18 years) and 290 females (mean age 49.51 ± 0.25 years). According to the six-grade ultrasonographic classification system, the distribution of hepatic steatosis severity was as follows: 800 cases (26.6%) were classified as Grade 0, 1,131 cases (37.7%) as Grade 1, 431 cases (14.4%) as Grade 2, 437 cases (14.6%) as Grade 3, 117 cases (3.9%) as Grade 4, and 86 cases (2.9%) as Grade 5.

Correlation analysis and dose-response relationship between FBG and hepatic steatosis severity

As FBG values were not normally distributed, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was employed. The results indicated a weak positive correlation between FBG levels and the severity of hepatic steatosis (ρ = 0.285, 95% CI [0.251, 0.318], P < 0.001). This trend was visually supported by a boxplot (Fig. 1), which showed progressively higher FBG distributions with increasing severity. The Kruskal-Wallis test confirmed significant differences in median FBG across severity groups (χ2 = 257.747, P < 0.001).

To quantify the dose-response relationship between the severity of hepatic steatosis and FBG levels, multiple linear regression analysis was employed (see the dedicated summary in Table 1). After adjusting for age, BMI, blood pressure, and other metabolic indicators in a multivariate model (Table 2), hepatic steatosis severity remained a significant independent predictor. For each 1-grade increase in steatosis grade, FBG levels increased by an average of 0.179 mmol/L (95% CI 0.116–0.242, P < 0.001).

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that the grade 0 (no steatosis) group had significantly lower FBG levels than all steatosis-positive groups (grades 1–5, all P < 0.001). These results consistently demonstrate that higher hepatic steatosis severity is associated with elevated FBG in a significant and dose-dependent manner.

Multiple linear regression analysis of metabolic indicators with FBG and hepatic steatosis severity

Preliminary univariate analysis revealed that all measured metabolic indicators showed statistically significant differences across the six hepatic steatosis severity groups (all p < 0.05, see Supplementary Table S2). This justified our subsequent use of multivariate regression models to identify independent predictors.

To identify independent associations between metabolic indicators and both FBG levels and hepatic steatosis severity, we employed multiple linear regression and generalized ordered logistic regression models, respectively. This approach allows assessment of each predictor’s contribution while adjusting for other variables in the model.

For FBG levels, the multiple linear regression model (Table 2) was statistically significant (F = 31.687, p < 0.001) with an adjusted R2 of 0.159. Results showed that AGE, SBP, TG, BUN, HGB, and hepatic steatosis severity were significant independent positive predictors of FBG. Specifically, each 1-grade increase in steatosis grade was associated with an average increase of 0.179 mmol/L in FBG levels (the dose-response relationship is detailed in Table 4). Diastolic blood pressure and uric acid were significant negative predictors.

For hepatic steatosis severity, the generalized ordered logistic regression analysis revealed dynamic characteristics of influencing factors (Table 3). AGE, BMI, TG, and ALT, as non-proportional effect variables, showed significant variations in their effect strengths with disease progression (all p < 0.001). Specifically:

AGE acted as a risk factor in the mild (OR = 1.037) and mild-to-moderate (OR = 1.014) stages but transitioned to a protective factor in the moderate-to-severe (OR = 0.969) and severe (OR = 0.943) stages.

BMI was a significant risk factor across all severity grades, with its effect strength showing a U-shaped trend, peaking in the mild stage (OR = 1.323).

TG’s risk effect progressively intensified with disease advancement (OR ranging from 1.111 to 1.222).

ALT’s effect strength continuously increased with disease severity (OR ranging from 1.004 to 1.028).

Among the proportional effect variables, FBG (OR = 1.090), LDL-C (OR = 1.079), UA (OR = 1.001), and mean arterial pressure (OR = 1.006) were persistent risk factors, while HDL-C (OR = 0.668) and the AST/ALT ratio (OR = 0.848) were significant protective factors.

Integrated predictive performance of key metabolic indicators

To identify the most clinically relevant indicators for risk stratification, we focused our analysis on the predictive performance for the co-occurrence of MAFLD and abnormal FBG, which represents the core outcome of this study. A comprehensive ROC analysis was performed, and the results for the key predictors are synthesized in Table 4.The corresponding ROC curves for predicting the coexistence of MAFLD and abnormal FBG are presented in Fig. 4.

For the primary outcome of MAFLD and abnormal FBG coexistence, Body Mass Index (BMI) demonstrated outstanding discriminative ability (AUC = 0.906), followed by triglycerides (TG) (AUC = 0.795) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) (AUC = 0.777), which showed excellent performance. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) exhibited good discrimination (AUC = 0.749).

The predictive performance of these key indicators for the individual conditions—MAFLD alone and abnormal FBG alone—was also assessed to validate their broader metabolic role (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively). This analysis confirmed that BMI, TG, and ALT also showed good to excellent discrimination for MAFLD alone (AUCs = 0.873, 0.740, and 0.720, respectively). Their performance for predicting abnormal FBG alone was more modest but statistically significant (AUCs presented in Table 4), underscoring their specific utility in identifying the comorbid condition rather than isolated dysglycemia (Fig. 4).

This integrated analysis establishes BMI, TG, and SBP as the most powerful and consistent predictors for identifying individuals with coexisting MAFLD and abnormal glucose metabolism.

Discussion

The rising incidence rates of MAFLD and T2DM present a significant global health challenge, with projections indicating that the global prevalence of MAFLD in adults will exceed 55% by 204016. This concerning trend is further substantiated by cohort studies demonstrating that MAFLD patients have a significantly higher risk of developing diabetes compared to non-MAFLD individuals17. Within this clinical context, our cross-sectional study systematically evaluated the associations between routine metabolic indicators and both fasting blood glucose levels and the severity of hepatic steatosis in MAFLD.

Our primary finding reveals a significant dose-response relationship between the severity of hepatic steatosis and FBG levels, with each 1-grade increase in steatosis grade independently associated with a 0.179 mmol/L elevation in FBG after adjusting for multiple metabolic confounders. This association finds mechanistic support in established pathophysiological pathways involving insulin-resistant adipocytes releasing free fatty acids that lead to accumulation of toxic triglyceride-derived metabolites in the liver, thereby explaining how T2DM influences MAFLD onset and progression18,19. Furthermore, our generalized ordered logistic regression model uncovered dynamic characteristics of influencing factors throughout hepatic steatosis progression, with the progressively strengthening effects of TG and ALT particularly highlighting the crucial roles of lipotoxicity and inflammation in disease advancement.

Regarding clinical translation, we identified BMI, TG, and SBP as key predictors for detecting the comorbidity of MAFLD and abnormal FBG. The clinical utility of our established cut-off values receives support from existing literature: the BMI threshold of 24.835 kg/m2 falls within the overweight range according to Asian-specific criteria, aligning with studies demonstrating the significant T2DM burden attributable to high BMI20; the ALT cut-off of ≥ 26.5 IU/L corresponds with long-term follow-up studies establishing the association between elevated ALT levels and T2DM risk21; and the BUN threshold of ≥ 6.25 mmol/L finds validation in prospective cohort studies22. Particularly noteworthy is the significant disparity between our identified SBP and DBP critical values, which aligns with research emphasizing the role of pulse pressure differences in diabetes risk assessment23, while blood pressure stratification has been consistently shown to aid in predicting MAFLD progression24.

Our study also identified an association between hemoglobin levels and glucose metabolism disorders, a finding that resonates with gestational diabetes research showing that elevated HGB levels correlate with increased gestational diabetes mellitus risk25, suggesting hemoglobin’s potential as a biomarker for dysglycemia screening.

Compared with previous investigations, our analysis not only confirms the significant role of established risk factors26,27,28,29 but also advances the field by integrating multi-indicator predictive performance and establishing specific cut-off values. These findings, combined with established evidence that ALT monitoring facilitates early MAFLD detection30, collectively contribute to comprehensive MAFLD management strategies31,32,33,34,35. Our results align well with current guidelines emphasizing integrated management of obesity and related metabolic disorders36,37.

Our study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of causal relationships. The sample was derived from a single center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the lack of direct measurements of insulin resistance and histopathological validation of liver status represents a notable constraint. While the ultrasound-based diagnosis employed here offers clinical utility, it is inherently subjective. Future studies should validate the predictive efficacy of these cutoff values through prospective designs and incorporate multi-omics data to further explore underlying mechanisms.

Conclusion

In this large cross-sectional study, we observed significant associations between routine metabolic indicators, particularly BMI, TG, and SBP, and the co-occurrence of MAFLD and abnormal fasting blood glucose. The optimal cut-off values identified in our analysis may serve as practical thresholds for early risk stratification in clinical settings.

These findings, while derived from an observational study and requiring further validation in prospective cohorts, provide translational evidence that supports the integrated management of metabolic abnormalities. We suggest that monitoring these readily available indicators could help identify high-risk individuals who may benefit from early intervention strategies aimed at preventing the progression of both MAFLD and dysglycemia.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lim, G. E. H. et al. An observational data Meta-analysis on the differences in prevalence and risk factors between MAFLD vs NAFLD. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21 (3), 619–629e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.038 (2023).

Eslam, M. & George, J. Reply to: Correspondence regarding A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement: bringing evidence to the NAFLD-MAFLD debate. J. Hepatol. 73 (6), 1575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.045 (2020).

Kaya, E. & Yilmaz, Y. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): A Multi-systemic disease beyond the liver. J. Clin. Transl Hepatol. 10 (2), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.14218/JCTH.2021.00178 (2022).

Dai, C. Y. et al. Reconstruction of the hepatic microenvironment and pathological changes underlying type II diabetes through Single-Cell RNA sequencing. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 20 (14), 5531–5547. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.99176 (2024).

Zeng, J. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of MAFLD in Chinese adults aged 40 years or older: A community-based study. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 21 (2), 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbpd.2022.01.006 (2022).

Farrugia, M. A. et al. Incretins and MAFLD: At the crossroads of endocrine and hepatic disorders. Curr. Obes. Rep. 14 (1), 56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-025-00646-8 (2025). Published 2025 Jun 25.

Jung, I., Koo, D. J. & Lee, W. Y. Insulin resistance, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Clinical and experimental perspective. Diabetes Metab. J. 48 (3), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2023.0350 (2024).

Sun, D. Q. et al. An international Delphi consensus statement on metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and risk of chronic kidney disease. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr.. 12 (3), 386–403. https://doi.org/10.21037/hbsn-22-421 (2023).

Ohno, R. et al. Oct. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with risk of HF and AF. J. ACC. Asia. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacasi.2023.08.003 (2023).

Fouad, Y., Alboraie, M. & Shiha, G. Epidemiology and diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol. Int. 18 (Suppl 2), 827–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-024-10704-3 (2024).

Matsubayashi, Y. et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease on cardiovascular risk by the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes and according to sex. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21 (1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01518-4 (2022).

Mellemkjær, A., Kjær, M. B., Haldrup, D., Grønbæk, H. & Thomsen, K. L. Management of cardiovascular risk in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 122, 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2023.11.012 (2024).

Golabi, P. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and associated mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes, pre-diabetes, metabolically unhealthy, and metabolically healthy individuals in the united States. Metabolism 146, 155642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155642 (2023).

Li, T., Wang, Y., Zhao, S., Cui, Y. & Qu, Z. A nomogram incorporating clinical and laboratory indicators for predicting metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients. J. Diabetes Investig. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.70112 (2025).

Cui, Y., Qu, Z., Li, L. & Hu, W. Gender difference in the association between serum uric acid and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. BMC Gastroenterol. 25 (1), 322. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-025-03917-9 (2025).

Younossi, Z. M., Kalligeros, M. & Henry, L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 31 (Suppl), S32–S50. https://doi.org/10.3350/cmh.2024.0431 (2025).

Liang, Y. et al. Association of MAFLD with diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease: A 4.6-Year cohort study in China. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107 (1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab641 (2022).

Han, E. et al. Association of temporal MAFLD with type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and mortality. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 24 (1), 289. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-025-02824-3 (2025).

Sakurai, Y., Kubota, N., Yamauchi, T. & Kadowaki, T. Role of insulin resistance in MAFLD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (8), 4156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22084156 (2021). Published 2021 Apr 16.

Huang, X., Wu, Y., Ni, Y., Xu, H. & He, Y. Global, regional, and National burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus caused by high BMI from 1990 to 2021, and forecasts to 2045: analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Public. Health. 13, 1515797. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1515797 (2025). Published 2025 Jan 23.

Folli, F. et al. Alanine transferase levels (ALT) and triglyceride-glucose index are risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus in obese patients. Acta Diabetol. 61 (4), 435–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-023-02209-6 (2024).

Li, S. N. et al. Association between blood Urea nitrogen and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Chinese population: a cohort study. Endocr. J. 68 (9), 1057–1065. https://doi.org/10.1507/endocrj.EJ20-0794 (2021).

Wu, C., Ma, D. & Chen, Y. Association of pulse pressure difference and diabetes mellitus in Chinese people: A cohort study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 6601–6608. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S327841 (2021). Published 2021 Oct 11.

Liu, J. et al. Blood pressure stratification for predicting liver fibrosis risk in metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 28 (2), 100892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2022.100892 (2023).

Yang, X. et al. Impact of hemoglobin level on the association between lipid metabolism and gestational diabetes mellitus: A retrospective study. Med. (Baltim). 104 (10), e41778. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000041778 (2025).

Yao, Z. et al. Associations between class I, II, or III obesity and health outcomes. NEJM Evid. 4 (4), EVIDoa2400229. https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDoa2400229 (2025).

Dicker, D., Karpati, T., Promislow, S. & Reges, O. Implications of the European association for the study of obesity’s new framework definition of obesity: Prevalence and association with All-Cause mortality. Ann. Intern. Med. 178 (8), 1065–1072. https://doi.org/10.7326/ANNALS-24-02547 (2025).

Chew, N. W. S. et al. The global burden of metabolic disease: Data from 2000 to 2019. Cell. Metab. ;35(3):414–428e3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.02.003 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Global burden of metabolic diseases, 1990–2021. Metabolism 160, 155999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2024.155999 (2024).

Wang, D., Zhou, B. Y., Xiang, L., Chen, X. Y. & Feng, J. X. Alanine aminotransferase as a risk marker for new-onset metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 30 (25), 3132–3139. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i25.3132 (2024).

Bao, S., Jin, Q., Wang, T., Mao, Y. & Huang, G. Predicting the risk of lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease based on interpretable machine models in a Chinese T2DM population. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 16, 1626203. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1626203 (2025). Published 2025 Jul 11.

Cui, Y. et al. A nomogram for predicting metabolic-associated fatty liver disease in non-obese newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 16, 1521168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1521168 (2025). Published 2025 May 29.

Peng, H. et al. Prediction of MAFLD and NAFLD using different screening indexes: A cross-sectional study in U.S. Adults. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1083032. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1083032 (2023). Published 2023 Jan 19.

Lei, X. et al. Serum isthmin-1 is a potential biomarker for metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease in patients with metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 12 (5), e004514. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2024-004514 (2024). Published 2024 Sep 25.

Yang, B. & Zhong, X. Clinical model to predict the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A secondary analysis of data from a cross-sectional study. Med. (Baltim). 103 (36), e39437. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000039437 (2024).

Bellicha, A. et al. Effect of exercise training on weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: An overview of 12 systematic reviews and 149 studies. Obes. Rev. 22 (Suppl 4(Suppl 4), e13256. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13256 (2021).

Dikaiou, P. et al. Obesity, overweight and risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality in young women. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 28 (12), 1351–1359. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320908983 (2021).

Funding

This study was supported by the Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Program (Grant No. 20220401059YY).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Q. was responsible for manuscript writing, revision, as well as data curation, statistical analysis, and interpretation. S.J. contributed to data statistical analysis. Y.S. was responsible for study conception and supervision. W.Z. and D.C. performed data verification. Z.W. provided critical guidance and supervision of the project. Y.L. contributed to manuscript revision and scientific guidance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Changchun University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Approval Number: CCZYFYLL-SQ-2025审字-252), and complies with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration. This project is a retrospective study and does not involve any intervention on the subjects.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, X., Jin, S., Shi, Y. et al. The association of multiple metabolic disorders with the severity of fasting blood glucose and hepatic steatosis in a Chinese population with MAFLD: a cross-sectional study of over 3000 participants. Sci Rep 15, 43855 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31652-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31652-4