Abstract

Evaluating the suitability of deceased organ donor kidneys relies on clinical, laboratory, and biopsy data. Pathologist quantitation of glomerulosclerosis is a critical histologic parameter used in the decision to transplant. This is an arduous task with modest reproducibility and inconsistent correlation with graft outcomes. Prior work shows that deep learning methods automate glomerulosclerosis quantitation with performance superior to on-call pathologists. Extending beyond this prior work, in this study we find that deep learning glomerulosclerosis quantitation better correlates with graft outcomes. A customized and updated deep learning model was used to analyze 691 procurement biopsies of transplanted kidneys with an average recipient follow up of 4.34 ± 1.90 years. The model evaluates a whole slide image in 26.5 +/- 6.3 s. Both pathologist and deep learning model quantitation of glomerulosclerosis significantly correlated with recipient glomerular filtration rate. A multivariate Cox model was developed using glomerulosclerosis, the Kidney Donor Profile Index, cold ischemia time, and recipient age, body mass index, and history of diabetes. Deep learning quantitation of glomerulosclerosis, but not pathologist quantitation, correlated with graft survival after adjusting for other clinical and laboratory parameters. These results show deep learning quantitation of glomerulosclerosis can perform at the speed of clinical care and shows superior performance for graft outcomes, potentially optimizing kidney transplant decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Procurement kidney biopsy results are the primary factor in the decision to transplant or discard an organ1,2. Linking biopsy results with organ discards raised concerns that biopsies are doing more harm by providing a false sense of reassurance to surgeons based on unreliable information3,4. It is important to understand whether donor biopsy evaluation by pathologists provides reliable data that correlates with graft outcomes.

There is a critical and expanding shortage of donor kidneys in the United States5. Approximately 100,000 patients are on the donor kidney waitlist and 5,000 patients die every year waiting for an organ6,7. Despite high demand, approximately 3,500 kidneys are discarded in the United States every year6. The Advancing American Kidney Health initiative has prioritized reducing kidney discards to improve transplantation access in the United States8.

Discarded organs are perceived to be of inadequate quality and are typically from older, expanded criteria donors (ECD)1,6,9. However, many of these organs are potentially transplantable6,10,11. Biopsies are performed in approximately half of all deceased donor kidneys and over 85% of ECD kidneys4.

Prior studies have linked chronic damage in donor kidney biopsies with graft outcomes12,13,14,15,16,17,18. The percentage of globally sclerotic glomeruli is a key component of determining chronic kidney damage. Several histopathology scoring systems, all using percent global glomerulosclerosis among other metrics, have been described to assist with the decision to use or discard an organ. However, no scoring system has been accepted as best practice4. Regardless of the scoring system used, investigations have demonstrated variability in all aspects of pathologic examination resulting in misclassification of organ quality, contributing to the high organ discard rate2,11,12,19,20,21,22,23. Variation in pathology results reflects several factors including tissue freezing artifact, non-kidney specialist evaluation, manual quantitation of chronic damage, and demand for rapid results in off hours24,25.

Since Gaber’s publication in 1995 identifying 20% global glomerulosclerosis as an inflection point in determining graft survival, surgeons have relied on this metric in their decision to use a kidney17. Kasiske et al. reported that > 20% glomerulosclerosis independently correlated with the decision to discard21. The current standard is for a pathologist to examine frozen kidney tissue and manually count glomeruli to determine percent global glomerulosclerosis. When biopsies are assessed by expert renal pathologists, results are more consistent and show correlation with outcomes19. However, in practice, pathologists without renal pathology expertise are evaluating donor kidneys, demonstrating poor reproducibility and lacking significant correlation with outcomes19,20,22. Expert renal pathologist biopsy review results in 20% more organs classified as transplantable19. Development of techniques to improve on-call pathologist performance is critical to maximize procurement biopsy utility and decrease the discard rate associated with overestimation of chronic damage.

Digitization of glass slides is increasingly utilized in pathology practice. With creation of whole slide images (WSI), there is an opportunity to incorporate artificial intelligence tools to assist pathologists with quantitative demands that are less accurate when performed by humans26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. The process of slide digitization followed by pathologist examination using a screen instead of a scope is transforming the field. By deploying artificial intelligence methods to identify, quantify, and classify WSIs, the field of surgical pathology becomes more quantitative and precise. There is an opportunity for pathologists to leverage this technology to improve efficiency and reproducibility and to unlock WSI features that have not been previously appreciated in their significance to disease pathophysiology and prognosis. While promising, a key challenge to the adoption of artificial intelligence image analysis technology in clinical workflows is that the most advanced models are time-consuming and costly to deploy into practice.

Image analysis technology uses deep learning networks (DL). DL models have been studied predominantly for cancer detection and classification and have more recently been applied to kidney biopsy evaluation27,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. We published the first study utilizing a DL model to quantify non-sclerotic and sclerotic glomeruli in donor kidney biopsy frozen section WSI39,40. This technology rapidly and robustly discriminates sclerotic from non-sclerotic glomeruli with improved accuracy compared with general surgical pathologists39. Others have published similar results46,47.

Automated quantitation of percent global glomerulosclerosis in kidney biopsies minimizes variability and improves accuracy on par with expert renal pathologists39,40. The aim of this study is to develop a glomerulosclerosis DL model capable of performing at a speed compatible with clinical care and to evaluate model correlation with graft outcomes compared with pathologist quantitation, the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI), and other recipient factors.

Materials and methods

Pathology data and study cohort

The study was approved by the Washington University Internal Review Board (IRB#201808179) and carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All kidney biopsy samples are deidentified and from deceased individuals. Consent to use the material is waived by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office. The study used data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The OPTN data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN contractor. All OPTN data is deidentified and consent waived per the Internal Review Board. WSIs were obtained from the Washington University School of Medicine Department of Pathology and Immunology archive of procurement biopsies referred to Washington University for routine care during 2015–2021. Intraoperative examination was performed by individual board-certified, attending surgical pathologists. The examined data set consists of 329 cases (651 WSI) of H&E-stained frozen wedge and 362 cases (723 WSI) of permanent core procurement biopsies retrieved from a total of 691 kidneys. Biopsy WSI originated from Gift of Life Michigan, using a Sakura scanner; Washington University, using an Aperio Scanscope CS scanner, OneLegacy, using a Grundium scanner, LifeSharing San Diego using a Grundium scanner, and Iowa Donor Network using a Grundium scanner. All scans were at 20x resolution (approximately 0.5 μm/pixel) and stored in SVS format.

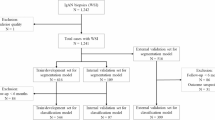

The Washington University digital biopsy archive was searched for deceased organ donor kidney biopsies. Discarded organs were not included in the analysis (n = 830). WSIs from kidneys used to develop the DL model (n = 153) and WSI with incompatible file formats (n = 903) were excluded from analysis.

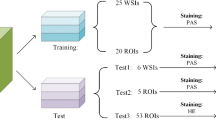

Training data and annotation

A different dataset was used train the neural network model, consisting of 235 WSI consisting of 155 frozen section wedge biopsies and 80 rapid permanent core biopsies. WSI were annotated by expert renal pathologists as previously described33,39. Glomeruli were classified as globally sclerotic (defined as sclerosis involving the entire glomerular tuft, including obsolescent, solidified and disappearing global glomerulosclerosis) or non-globally sclerotic. All other areas were grouped together and labeled as tubulointerstitium. A total of 2,261 globally sclerosed and 10,622 non-globally sclerosed glomeruli were annotated by expert renal pathologists in 235 distinct WSI corresponding to 235 individual kidney biopsies. The biopsies exhibited a wide range of percent global glomerulosclerosis (0% to 72%). Mean number of glomeruli per WSI was 54.8 ± 30.2. The 82 additional biopsies were from samples collected after 2021 and were not included in the graft survival analysis. No WSI preprocessing was performed prior to training or testing.

An entirely separate set of 529 WSI obtained during routine clinical care from December, 2024 through May, 2025 was utilized for DL model speed characterization.

Deep learning model architecture

Unlike our prior work which utilized a fully convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the VGG16 architecture and pretrained bottleneck weights56,57, the model used in this study was a CNN trained from scratch with architecture described graphically in Fig. 1. Briefly, five convolution/maxpool layers were fed into 4 fully convolutional layers and a final 1 × 1 convolutional layer with 4 output channels. This architecture was chosen because it is compact, with only 668,772 parameters, just 2.6 megabytes. Small models, such as this, are easier to deploy into practice than larger models. The fully convolutional model generated pixel maps registered to the input WSI, giving the probability that each output pixel was background, tubulointerstitium, non-globally sclerosed glomerulus, or globally sclerosed glomerulus. Since the DL model’s output was downsampled (i.e. at a lower resolution) by a factor of 32 relative to the original WSI, the associated annotation map was similarly downsampled to produce a training target.

This model was designed to be is feasibly applied in clinical practice, requiring approximately about 26.5 ± 6.3 s to run on a WSI in a cloud-optimized deployment. This implementation is heavily parallelized. Each worker processes a fixed size area of the slide, which is then reassembled into the final prediction. Consequently, larger slides utilize proportionally more workers, and inference time is nearly constant.

Training parameters

235 WSI were used to train the model. Each WSI was diced into 1,214 × 1,214-pixel (607 × 607 μm at 0.5 μm per pixel) partially overlapping WSI patches (stride = 768 pixels, or 384 μm) for training input. The precise size of patches used for training is not a critical parameter, because the network can be applied to arbitrary-sized images. Training data was augmented by randomly flipping or rotating (by 0/90/180/270˚) input and target patches. Training was performed using the TensorFlow framework by minimizing categorical cross-entropy loss, weighted class-wise using a ratio of 10:5:1:1 for sclerosed, non-sclerosed, tubulointerstitial, and background categories, respectively, reflecting the approximate difficulty and importance of identifying each class. Stochastic gradient descent optimization was used with a cyclic learning rate of 1e − 6 and batch size of 4 for 15 epochs.

Cross validation

The model was trained and tested in a 10-fold cross-validation scheme, where 10% of the 235 WSIs were withheld from training, and the resulting trained model was used to generate predictions on the withheld WSIs. WSIs from different levels of the same kidney were always held out together to avoid bias. Predictions for withheld WSI were generated patch-wise, and the results were reassembled to produce output probability maps for WSIs. Correlation between model prediction and ground truth annotations was obtained with results from the 10 cross-validation models to evaluate robustness and accuracy. The final model was trained once using 235 WSI in the training set and then applied to the primary dataset of 691 WSI.

Post processing

A standard Laplacian-of-Gaussian blob-detection algorithm34 was used to localize individual glomeruli from the probability maps to obtain glomeruli counts. Glomerulosclerosis was computed by the formula S/N, where S = number of globally sclerosed glomeruli, and N = total glomeruli count. Where multiple section levels were available for a kidney, the number of normal and sclerosed glomeruli were summed before computing percent glomerulosclerosis.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure is graft failure defined as return to dialysis or a decrease in renal function below a GFR of 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 as calculated by the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. Transplant recipients who die with functioning grafts are treated as censored outcomes. Simple linear regression analysis was performed to examine the linear relationship between recipient creatinine and procurement biopsy findings. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were obtained for both model and pathology results using various cutoffs and Logrank test was used to compare survival between groups. Univariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine risk factors associated with graft failure time. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was built using backward model selection method. Hazard ratio and 95% CI were reported. Various cutoffs of percentages of glomerulosclerosis quantified by the DL model as a predictor of graft failure were assessed in Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. P-value and AIC (model fit statistic) were used to select the optimal cutoffs. All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical analysis was performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Deep learning model

We compared the performance of our previously described pretrained- DL model with the new DL model developed in this study39. The performance of the new DL model was compared with the pretrained VGG16-based model, using the same 235 slide training dataset. Models were evaluated by comparing correlations with ground truth data using cross-validation. The new model improved correlation with ground truth using pooled WSI data (r = 0.944, RMSE = 0.053 vs. 0.922, RMSE = 0.60) (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Correlation with ground truth annotation for normal glomeruli improved from r = 0.972, RMSE = 13.324 to r = 0.988, RMSE = 7.811. Sclerotic glomeruli identification showed similar improvement using the new model to r = 0.941, RMSE 7.306 from r = 0.916, RMSE = 8.428 using the pretrained model (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Two measures of similarity used in assessing image segmentation algorithms are the Dice coefficient and the intersection-over-union (IOU) metric. The Dice coefficients improved using the new model from 0.742 to 0.529 to 0.820 and 0.637 for non-sclerotic and sclerotic glomeruli, respectively. Similar improvement was seen for IOU. For non-sclerotic and sclerotic glomeruli, the IOU improved from 0.590 to 0.360 to 0.696 and 0.467 (Table 1). Since the new model showed superior performance, this model was used to analyze the complete dataset. The new model is referred to as the DL model in the remainder of the study.

Comparison of DL models with and without pre-training. (A) Percent glomerulosclerosis quantified using a pre-trained DL model. (B) Non-globally sclerosed glomeruli quantitation using a pre-trained DL model. (C) Globally sclerosed glomeruli quantitation using a pre-trained DL model. (D) Percent glomerulosclerosis quantified using a DL model without pre-training. (E) Non-globally sclerosed glomeruli quantitation using DL model without pre-training. (F) Globally sclerosed glomeruli quantitation using a DL model without pre-training.

We also measured the time required to apply the model to new WSI. 529 procurement kidney biopsy WSIs were evaluated using the new DL model and timed in a cloud-optimized deployed version of the model. Excluding the time to scan the glass slides, the DL model was able to process a slide in 26.5 ± 6.3 s (Fig. 3). The processing time does not vary with the number of WSI since the model is capable of processing in parallel.

Transplant donor and recipient characteristics

A total of 2,598 procurement kidney biopsies were analyzed at Washington University during 2015–2020. Of the biopsied kidneys, 830 were discarded and 1,768 were transplanted. The 153 biopsies used in DL model development were excluded from analysis. The additional 82 biopsies used for training were recent biopsies and not within the dataset. 903 biopsies had incompatible WSI file formats and were excluded. Seven patients were excluded due to disease recurrence and 14 were excluded whose grafts were lost within 30 days of transplant for a final dataset of 691 kidneys consisting of 1,374 WSI (Fig. 4). Since early graft loss is more likely to be related to vascular accidents and acute rejection rather than pre-existing chronic damage, these were excluded from analysis48. The donor and recipient characteristics are detailed in Table 2. The average recipient age was 58.20 ± 11.10 years and donor age were 44.53+/-12.84 years. No patients received a prior transplant or an ABO incompatible kidney transplant. Recipients were followed for an average of 4.34 ± 1.90 years (range 0.15–9.08 years). Most transplant recipients were on dialysis prior to transplant (89.00%, n = 615). Of the donors, 12.16% (n = 84) had a history of diabetes and 41.39% (n = 286) a history of hypertension. Delayed graft function, defined as requiring dialysis within 1 week of transplant, occurred in 29.86% of recipients (n = 206). 4.78% of kidneys failed during the total follow up period. Of the failed grafts, the average graft survival time was 3.47 ± 1.90 years (range 0.12–7.72 years).

Procurement kidney biopsy findings

Biopsy reports were used to determine the intraoperative on-call pathologist results. Pathologists reported an average of 3.71 ± 5.07% global glomerulosclerosis. In comparison, the DL model reported an average of 5.43 ± 6.7% global glomerulosclerosis (Table 2). The intraoperative pathologists counted one section level where the DL model evaluated two levels, accounting for the total glomeruli count differences (Table 2). The intraoperative pathologist quantitation of percent global glomerulosclerosis showed good correlation with the DL model results (r = 0.615, RMSE = 5.648, p = < 0.0001, Fig. 5). Intraoperative pathologist semi-quantitation of arteriosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis was captured. Interstitial fibrosis was semi-quantified as none (58.63%, n = 401), minimal (5.85%, n = 40), mild (34.21%, n = 234), mild-moderate (1.17%, n = 8), or severe (0.15%, n = 1). Arteriosclerosis was reported as none (39.21%, n = 269), minimal (5.39%, n = 37), mild (43.0%, n = 295), mild-moderate (11.37%, n = 78), or severe (1.02%, n = 7).

Association between procurement biopsy findings and recipient outcomes

Simple linear regression was used to correlate procurement biopsy findings with recipient creatinine (log-transformed to meet normality) and GFR (Fig. 6). Pathologist and model quantitation did not show significant correlation with the most recent creatinine after transplant (adjusted r2 = 0.0048, p = 0.0715 & adjusted r2 = 0.0033, p = 0.1365, respectively). A significant inverse correlation was observed with estimated GFR for pathologist and model quantitation (r2 = 0.0126, p = 0.0031 and r2 = 0.0126, p = 0.0031, respectively).

Graft survival time was calculated from date of donation to date of graft failure or censored at the date of last follow up. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated separately for 15, 20, and 25% global glomerulosclerosis. Pathologist quantitation of percent global glomerulosclerosis did not reach statistical significance for any values. Model quantitation showed significant reduction in death-censored graft survival over time in organs with > 25% global glomerulosclerosis, a finding that was not observed with on-call pathologist quantitation of glomerulosclerosis (Fig. 7A and B). A sensitivity analysis was performed. A cutoff of 25% show a significantly greater likelihood of progressing to graft failure (Table 3).

DL model and on-call pathologist quantitation of glomerulosclerosis correlation with kidney function and graft survival on a per kidney basis. (A) Correlation between creatinine and DL model quantitation of glomerulosclerosis. (B) Correlation between glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and DL model quantitation of glomerulosclerosis. (C) Correlation between creatinine and on-call pathologist quantitation of glomerulosclerosis. (D) Correlation between GFR and on-call pathologist quantitation of glomerulosclerosis.

Kaplan-Meier survival probability using DL model or on-call pathologist quantitation of glomerulosclerosis. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival probability of kidneys with > 20% glomerulosclerosis quantified using the DL model. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival probability of kidneys with > 20% glomerulosclerosis quantified by on-call pathologists. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival probability of kidneys with > 25% glomerulosclerosis quantified by on-call pathologists. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival probability of kidneys with > 25% glomerulosclerosis quantified by on-call pathologists.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

Univariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine the association between graft survival time and biopsy results, KDPI, recipient age, recipient history of diabetes, recipient body mass index (BMI), and cold ischemia time (Table 4). The KDPI was obtained from the reported KDPI values within the OPTN database49. Biopsy results included model quantitation of glomerulosclerosis, on-call pathologist assessment of interstitial fibrosis, and on-call pathologist assessment of arteriosclerosis. The KDPI and DL model quantitation of glomerulosclerosis demonstrated significant association with graft survival time. Variables with p < 0.2 in the univariate analysis were considered in a multivariate analysis. The final multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was developed using backward selection method with either pathologist or the DL model derived percent global glomerulosclerosis forced in the model regardless of significance.

Using the pathologist derived percent global glomerulosclerosis data in multivariate analysis, only the KDPI remained significant (HR 1.013, 95% CI 1.001–1.025, p = 0.0344, Table 5. In contrast, the DL-model-derived quantitation of percent global glomerulosclerosis was significant after adjusting for KDPI (HR 1.029, 95% CI 1.001–1.058, p = 0.0407, Table 5). In both multivariate Cox models, KDPI was controlled for, meaning the effect of pathologist-derived or DL-model-derived percent global glomerulosclerosis on graft survival was assessed at any given value of KDPI (range 0-100).

Discussion

With the development of rapid and robust slide scanning technology, pathology laboratories are increasingly adopting digital workflows. Establishing a digital pathology workflow is a complex process requiring coordination and support from pathologists, technologists, and executive leadership50. One of the major drivers of digital pathology adoption is the myriad opportunities to deploy artificial intelligence technologies to assist pathologists with slide evaluation, improving efficiency, accuracy, and precision, ultimately improving patient care27,50,51,52,53,54.

Quantitation of glomerulosclerosis in procurement kidney biopsies is critical for determining organ usability. Adopting a digital workflow and quantifying glomerulosclerosis using an automated approach may improve correlation with outcomes independent of pathologist expertise and, ultimately, decrease unnecessary organ discard. A critical challenge to adoption in using DL in clinical workflows is that the most advanced models are difficult and costly to deploy into practice and robustly apply to WSI.

In this study, we describe a DL model that evaluates WSI in under 30 s, compatible with the needs of an intraoperative workflow. Using over 10,000 glomeruli from WSIs prepared from 5 different laboratories for training, the DL model robustly evaluates glomeruli despite routine artifacts related to differences in laboratory sectioning, staining, and frozen section. The model quantitation of percent global glomerulosclerosis in procurement kidney biopsies correlates with graft function and survival with superior results compared with pathologists and clinical parameters including the KDPI. Our previously reported DL model was modified by training a CNN without pretraining using non-pathology image data39,40. The new DL model showed superior performance compared with our initial model and was used to evaluate for outcome correlation using a large dataset with an average of greater than 4 years of follow up. On multivariate analysis, only the DL model-derived percent global glomerulosclerosis correlated with graft survival after adjusting for KDPI, organ cold ischemia time, recipient age, diabetes history, and BMI. Manual pathologist quantitation of percent global glomerulosclerosis did not significantly correlate with graft outcomes in a multivariate model.

When performed, procurement kidney biopsies are cited as the most important reason a donor organ is discarded1,21. Kidneys that are biopsied to evaluate quality prior to transplantation are three times more likely to be discarded1. Appropriately, the utility of procurement kidney biopsies has been questioned3. Biopsy results are variable and inconsistently correlate with graft outcomes4,11,23. While quantitation of chronic damage has been shown to correlate with outcomes, this correlation is dependent on the experience of the pathologist with kidney biopsies19,20. There are insufficient numbers of specialized renal pathologists to examine all donor kidney biopsies. Pathologists rely on visual, manual quantitation of chronic damage, a process that is prone to error and imprecision.

Automated quantitation of percent global glomerulosclerosis in procurement kidney biopsies using our DL model showed superior performance to the KDPI on multivariate analysis. Understanding the likelihood of graft survival before transplantation is essential to decide organ disposition. Since the initial observation linking procurement kidney biopsy percent global glomerulosclerosis and graft outcomes, procurement biopsies have become a standard technique to evaluate organ quality before transplantation17. However, despite the widespread use of biopsies in transplant decision-making, correlation of histopathology results with outcomes in a multivariate analysis has limited data3,4,11,46. The recent investigation by Reese et al. showed no incremental value in donor kidney histopathology findings beyond the Kidney Donor Risk Index in a multivariate analysis11. These results are based on the current standard manual pathologist assessment of chronic damage in kidney biopsies. In contrast, utilizing a DL model to quantify one histologic parameter, percent global glomerulosclerosis, showed significant correlation with graft survival after accounting for multiple donor and recipient factors. The recent publication by Yi et al. showed similar findings using a deep learning approach to quantitate multiple pathologic parameters on donor kidney biopsies46. Their results similarly showed performance as we describe and similar correlation with graft outcomes. While demonstrating impressive performance, their model reportedly requires approximately 30 min to process a WSI, thus making it challenging to meet the rapid speed needed in intraoperative consultation. Eccher et al. utilized the Aiforia platform to develop an artificial intelligence approach, termed Galileo, capable of evaluating a kidney procurement biopsy WSI in approximately 2 min to segment non-sclerotic glomeruli, sclerotic glomeruli, ischemic glomeruli, arteries, and arterioles with good accuracy and precision55. The Galileo algorithm performance in predicting graft outcomes has yet to be examined. Our simplified approach is capable of processing WSIs in under 30 s, with excellent glomerulosclerosis segmentation performance, overcoming a significant barrier that is needed for routine clinical care.

The study has several limitations. There is an inherent bias in the data since only organs perceived to be of sufficient quality were selected for transplantation. Evaluation of graft survival using kidneys with higher percentages of global glomerulosclerosis is limited to a small number. This could be overcome by incorporating a larger dataset from multiple institutions. The DL model was trained using WSI from 5 laboratories using 3 different types of scanners. The DL model needs to be evaluated in a larger, more variable dataset to ensure it can withstand the numerous variations in sample preparation and scanning that occurs in the routine practice of pathology. Enlarging the dataset from multiple sites with cases having up to 10 years of follow up could assist with exploring the longer-term correlations between automated quantitation of glomerulosclerosis and graft outcomes. This study is limited to automated quantitation of glomerulosclerosis. Other glomerular pathology such as periglomerular fibrosis, nodular glomerulosclerosis, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis may be encountered. These lesions are classified as non-sclerotic glomeruli by the model. Improved prognostic performance may be achieved if these are quantified. Pathologist semi-quantitation of arteriosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis were analyzed in the multivariate model and neither was associated with graft failure. Automated quantitation of these variables was not examined and may provide additional predictive value beyond glomerulosclerosis.

Our results show that rapid, automated quantitation of glomerulosclerosis in procurement kidney biopsy WSI correlates with graft survival independent of the KDPI. Developing a DL model using a neural network using kidney pathology WSIs only for training instead of kidney pathology WSIs in addition to non-pathology images improved model performance. We deliberately developed a simplified model that shows similar performance to larger and more complex models, yet is capable of processing WSI in under 30 s. These results demonstrate that there is value in evaluating kidney histopathology prior to transplantation and argue that biopsies should remain an integral part of the organ evaluation process. Deployment of DL models into the procurement biopsy clinical workflow is possible using a simplified model architecture. The results provide more reliable information to optimize organ utilization.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available for privacy reasons. They may be available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and IRB approval. The underlying code for this study is not publicly available due to licensing restrictions.

Abbreviations

- DL:

-

Deep learning

- ECD:

-

Expanded criteria donor

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- KDPI:

-

Kidney donor profile index

- WSI:

-

Whole slide image

References

Mohan, S. et al. Factors leading to the discard of deceased donor kidneys in the united States. Kidney Int. 94, 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.02.016 (2018).

Lentine, K. L. et al. Deceased donor procurement biopsy Practices, Interpretation, and Histology-Based Decision-Making: A survey of US kidney transplant centers. Kidney Int. Rep. 7, 1268–1277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2022.03.021 (2022).

Lentine, K. L., Kasiske, B. & Axelrod, D. A. Procurement biopsies in kidney transplantation: more information May not lead to better decisions. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 1835–1837. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2021030403 (2021).

Wang, C. J., Wetmore, J. B., Crary, G. S. & Kasiske, B. L. The donor kidney biopsy and its implications in predicting graft outcomes: A systematic review. Am. J. Transpl. 15, 1903–1914. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13213 (2015).

Tullius, S. G. & Rabb, H. Improving the supply and quality of Deceased-Donor organs for transplantation. N Engl. J. Med. 378, 1920–1929. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1507080 (2018).

Aubert, O. et al. Disparities in acceptance of deceased donor kidneys between the united States and France and estimated effects of increased US acceptance. JAMA Intern. Med. 179, 1365–1374. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2322 (2019).

Lewis, A. et al. Organ donation in the US and europe: the supply vs demand imbalance. Transpl. Rev. (Orlando). 35, 100585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trre.2020.100585 (2021).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Advancing American Kidney Health. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/262046/AdvancingAmericanKidneyHealth.pdf.

Lentine, K. L. et al. Variation in use of procurement biopsies and its implications for discard of deceased donor kidneys recovered for transplantation. Am. J. Transpl. 19, 2241–2251. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15325 (2019).

Massie, A. B. et al. Survival benefit of primary deceased donor transplantation with high-KDPI kidneys. Am. J. Transpl. 14, 2310–2316. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.12830 (2014).

Reese, P. P. et al. Assessment of the utility of kidney histology as a basis for discarding organs in the united states: A comparison of international transplant practices and outcomes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32, 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2020040464 (2021).

Liapis, H. et al. Banff histopathological consensus criteria for preimplantation kidney biopsies. Am. J. Transpl. 17, 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13929 (2017).

Munivenkatappa, R. B. et al. The Maryland aggregate pathology index: a deceased donor kidney biopsy scoring system for predicting graft failure. Am. J. Transpl. 8, 2316–2324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02370.x (2008).

Randhawa, P. Role of donor kidney biopsies in renal transplantation. Transplantation 71, 1361–1365. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-200105270-00001 (2001).

Singh, P. et al. Peritransplant kidney biopsies: comparison of pathologic interpretations and practice patterns of organ procurement organizations. Clin. Transpl. 26, E191–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01584.x (2012).

Sung, R. S. et al. Determinants of discard of expanded criteria donor kidneys: impact of biopsy and machine perfusion. Am. J. Transpl. 8, 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02157.x (2008).

Gaber, L. W. et al. Glomerulosclerosis as a determinant of posttransplant function of older donor renal allografts. Transplantation 60, 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199508270-00006 (1995).

Issa, N. et al. Kidney structural features from living donors predict graft failure in the recipient. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 31, 415–423. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2019090964 (2020).

Azancot, M. A. et al. The reproducibility and predictive value on outcome of renal biopsies from expanded criteria donors. Kidney Int. 85, 1161–1168. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.461 (2014).

Haas, M. Donor kidney biopsies: pathology matters, and so does the pathologist. Kidney Int. 85, 1016–1019. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.439 (2014).

Kasiske, B. L. et al. The role of procurement biopsies in acceptance decisions for kidneys retrieved for transplant. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 9, 562–571. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.07610713 (2014).

Sagasta, A. et al. Pre-implantation analysis of kidney biopsies from expanded criteria donors: testing the accuracy of frozen section technique and the adequacy of their assessment by on-call pathologists. Transpl. Int. 29, 234–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.12709 (2016).

Carpenter, D. et al. Procurement biopsies in the evaluation of deceased donor kidneys. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 1876–1885. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.04150418 (2018).

Emmons, B. R., Husain, S. A., King, K. L., Adler, J. T. & Mohan, S. Variations in deceased donor kidney procurement biopsy practice patterns: A survey of U.S. Organ procurement Organizations. Clin. Transpl. 35, e14411. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.14411 (2021).

Husain, S. A. et al. Reproducibility of deceased donor kidney procurement biopsies. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15, 257–264. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.09170819 (2020).

Ailia, M. J. et al. Current trend of artificial intelligence patents in digital pathology: A systematic evaluation of the patent landscape. Cancers (Basel) 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14102400 (2022).

Bullow, R. D., Marsh, J. N., Swamidass, S. J., Gaut, J. P. & Boor, P. The potential of artificial intelligence-based applications in kidney pathology. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 31, 251–257. https://doi.org/10.1097/MNH.0000000000000784 (2022).

Go, H. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence applications in pathology. Brain Tumor Res. Treat. 10, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.14791/btrt.2021.0032 (2022).

Esteva, A. et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 542, 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21056 (2017).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image Anal. 42, 60–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005 (2017).

Nagpal, K. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for Gleason grading of prostate cancer from biopsy specimens. JAMA Oncol. 6, 1372–1380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2485 (2020).

van der Laak, J., Litjens, G. & Ciompi, F. Deep learning in histopathology: the path to the clinic. Nat. Med. 27, 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01343-4 (2021).

Voulodimos, A., Doulamis, N., Doulamis, A. & Protopapadakis, E. Deep learning for computer vision: A brief review. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2018 (7068349). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7068349 (2018).

Yang, H. et al. Deep learning-based six-type classifier for lung cancer and mimics from histopathological whole slide images: a retrospective study. BMC Med. 19, 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-01953-2 (2021).

Litjens, G. et al. Deep learning as a tool for increased accuracy and efficiency of histopathological diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 6, 26286. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep26286 (2016).

Araujo, T. et al. Classification of breast cancer histology images using convolutional neural networks. PLoS One. 12, e0177544. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177544 (2017).

Niazi, M. K. K., Parwani, A. V. & Gurcan, M. N. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence. Lancet Oncol. 20, e253–e261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30154-8 (2019).

Huo, Y., Deng, R., Liu, Q., Fogo, A. B. & Yang, H. AI applications in renal pathology. Kidney Int. 99, 1309–1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2021.01.015 (2021).

Marsh, J. N., Liu, T. C., Wilson, P. C., Swamidass, S. J. & Gaut, J. P. Development and validation of a deep learning model to quantify glomerulosclerosis in kidney biopsy specimens. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2030939. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.30939 (2021).

Marsh, J. N. et al. Deep learning global glomerulosclerosis in transplant kidney frozen sections. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 37, 2718–2728. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2018.2851150 (2018).

Becker, J. U. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in nephropathology. Kidney Int. 98, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.02.027 (2020).

Barisoni, L., Lafata, K. J., Hewitt, S. M., Madabhushi, A. & Balis, U. G. J. Digital pathology and computational image analysis in nephropathology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16, 669–685. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-0321-6 (2020).

Santo, B. A. et al. PodoCount: A Robust, fully Automated, Whole-Slide podocyte quantification tool. Kidney Int. Rep. 7, 1377–1392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2022.03.004 (2022).

Shashiprakash, A. K. et al. A distributed system improves Inter-Observer and AI concordance in annotating interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 11603 https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2581789 (2021).

Goodman, K., Sarullo, K., Swamidass, S. J., Gaut, J. P. & Jain, S. Role of artificial intelligence in kidney pathology: promises and pitfalls. Kidney360 5, 1044–1046. https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0000000000000482 (2024).

Yi, Z. et al. A large-scale retrospective study enabled deep-learning based pathological assessment of frozen procurement kidney biopsies to predict graft loss and guide organ utilization. Kidney Int. 105, 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.09.031 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Deep learning segmentation of glomeruli on kidney donor frozen sections. J. Med. Imaging (Bellingham). 8, 067501. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JMI.8.6.067501 (2021).

Phelan, P. J. et al. Renal allograft loss in the first post-operative month: causes and consequences. Clin. Transpl. 26, 544–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01581.x (2012).

Rao, P. S. et al. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation 88, 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ac620b (2009).

Zarella, M. D. et al. A practical guide to whole slide imaging: A white paper from the digital pathology association. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 143, 222–234. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2018-0343-RA (2019).

Pantanowitz, L. et al. Twenty years of digital pathology: an overview of the road Travelled, what is on the Horizon, and the emergence of Vendor-Neutral archives. J. Pathol. Inf. 9, 40. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpi.jpi_69_18 (2018).

Rashidi, H. H., Chen, M. & Preface Artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning ML) and digital pathology integration are the next major chapter in our diagnostic pathology and laboratory medicine arena. Semin Diagn. Pathol. 40, 69–70. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semdp.2023.02.005 (2023).

Wu, B. & Moeckel, G. Application of digital pathology and machine learning in the liver, kidney and lung diseases. J. Pathol. Inf. 14, 100184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpi.2022.100184 (2023).

Koteluk, O., Wartecki, A., Mazurek, S., Kolodziejczak, I. & Mackiewicz, A. How do machines learn? Artificial intelligence as a new era in medicine. J. Pers. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11010032 (2021).

Eccher, A. et al. Galileo-an artificial intelligence tool for evaluating pre-implantation kidney biopsies. J. Nephrol. 38, 1163–1169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-024-02094-4 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the Mid-America Transplant Foundation award 012017 (J.P.G. and T.C.L.), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R42DK120253 (J.P.G) and R41DK120253 (J.P.G.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The data reported here have been supplied by UNOS as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P.G. and S.J.S. conceptualized and designed the study. J.N.M. and X.Y. collected the data and implemented the deep learning model. L.C and F.Z. provided biostatistics support. J.P.G., P.W., and T.C.L. annotated the whole slide images for ground truth determination and model development. J.P.G. and S.J.S. drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors of this manuscript have conflicts of interest to disclose. J.P.G., S.J.S., and J.N.M. may receive royalty income based on technology developed by J.P.G, S.J.S, and J.N.M. and licensed by Washington University to PlatformSTL. S.J.S. has an ownership interest in PlatformSTL and may financially benefit if the company is successful in marketing its products that are related to this research. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaut, J.P., Marsh, J.N., Chen, L. et al. Superior transplant recipient outcome prediction and pathology assessment using rapid deep learning applied to procurement kidney biopsies. Sci Rep 16, 1921 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31667-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31667-x