Abstract

As the complexity and unpredictability of cyber-physical systems (CPSs) such as multi-agent robotic networks increase, having robust predictive models is crucial for ensuring dependable operations. This paper presents a modification of the Strength Prominence (SP) index, which was initially designed for fuzzy social networks, adapted for use in robotic and intelligent automation systems. The SP index has been reformulated for fuzzy interaction graphs, where nodes signify robotic components and edges represent uncertain communications or dependencies. The modified index assesses link probability by considering the strength of connectedness and prominence levels, even in the absence of common neighbors. Theoretical aspects such as symmetry, boundedness, and monotonicity are thoroughly demonstrated. Empirical validation utilizing real-world datasets and ROS-based robotic data shows that the SP index achieves superior predictive accuracy, surpassing traditional fuzzy indices like CN, RSM, and CAR in terms of precision, AUC, and AUP measurements. This method allows for the early identification of interaction failures, improves the prediction of collaboration, and aids in the development of fault-tolerant designs. This proposed approach provides a new interdisciplinary tool for fuzzy link prediction in CPS, with important implications for the design of autonomous systems, real-time robotic collaboration, and resilient network structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent progress in intelligent automation and Industry 4.0 has driven the evolution of intricate cyber-physical systems (CPSs) like multi-agent robotic platforms, autonomous vehicles, collaborative human–machine interactions, and sensor-actuator networks. These systems are defined by dynamic topologies, decentralized management, diverse components, and continuous data flows, all functioning within uncertain or partially observable contexts. In these environments, achieving dependable coordination and strong communication among distributed elements presents a significant challenge. Conventional graph-theoretic modeling methods, which view inter-node connections as binary (i.e., either present or absent), fall short of adequately capturing the complex, variable nature of real-world interactions in CPSs. Conversely, fuzzy graph theory offers a more flexible and expressive modeling framework by enabling vertices and edges to possess varying degrees of membership—mirroring uncertainty in sensor outputs, inconsistent communication quality, or probabilistic task assignments. This fuzzy approach is particularly relevant in robotic systems, where link strength and node dependability frequently fluctuate due to signal degradation, latency, noise, and shifting task conditions. Therefore, creating predictive models capable of functioning amidst such uncertainty is crucial for fostering resilient and adaptive robotic actions. Fuzzy graph theory has become an effective tool for representing this ambiguity, facilitating more intricate representations where edges are not merely binary but weighted in accordance with degrees of similarity, belief, or uncertainty1.

A key issue in examining complex networks is link prediction, which involves estimating the probability of future or missing connections between nodes based on currently available information. In robotic contexts, such predictions can assist in forming autonomous collaborations, detecting failures, and adjusting network configurations dynamically2. Traditional link prediction methods like Common Neighbors (CN), Jaccard Index, Adamic-Adar, and Preferential Attachment concentrate on the local structural characteristics of the network3; however, they are inadequate for fuzzy or uncertain settings, especially when nodes may lack common neighbors.

In response to this issue, Pandey et al. have recently introduced the Strength Prominence (SP) index for fuzzy social networks, a unique similarity metric that takes into account both the strength of connections and the prominence level of nodes to effectively estimate link probabilities4. The SP index enhances previous fuzzy metrics such as the Resource Strength Model (RSM)5 and the CAR index6 by integrating the intensity of interactions along with the structural significance of the node. Their validation on Facebook datasets showed considerable improvements in prediction accuracy.

However, the SP index has yet to be adapted for use in technological or robotic networks, where nodes represent computational agents, sensors, or actuators, and edges represent communication or functional dependencies, often influenced by noise, signal degradation, or task uncertainty7. Each of these imperfections can be effectively represented using fuzzy values, making fuzzy interaction graphs especially applicable for modeling robotic cyber-physical systems (CPSs).

This study aims to fill this methodological void by modifying the SP index for interaction graphs that originate from robotics and automation. We reformulate the SP index within a domain-specific framework, where nodes symbolize robot modules or CPS components and edges reflect fuzzy interaction metrics—such as communication fidelity, shared task completion probability, or energy-aware collaborative intent.

The primary contributions of this paper include

-

1.

A mathematically grounded adaptation of the SP index for fuzzy cyber-physical interaction graphs, incorporating robot-specific parameters like signal strength, delay, and actuation frequency.

-

2.

A formal examination of characteristics such as symmetry, boundedness, and monotonicity under robotic fuzzy graph constraints.

-

3.

Empirical validation using ROS-based multi-agent simulation data and physical robot logs, assessing the SP index against CN, RSM, and CAR indices in terms of AUC, AUP, and Precision metrics.

-

4.

A demonstration of how fuzzy link prediction can be applied to pinpoint weak communication links, optimize task delegation, and enhance fault tolerance in robotics networks.

This interdisciplinary framework combines the accuracy of fuzzy graph theory with the practical requirements of robotics and CPS, offering a fresh and predictive perspective for future advancements in intelligent systems engineering.

Related work

The task of link prediction in uncertain or evolving contexts has garnered considerable interest in both social network analysis and research on cyber-physical systems (CPS). Initial approaches mainly depended on deterministic graph models that utilize binary edge existence; however, these models do not adequately represent the inherent ambiguity found in real-world interactions, especially within robotics and automation systems. To overcome this limitation, fuzzy graph theory has been suggested as a strong alternative, offering a framework in which both vertices and edges are assigned membership degrees that reflect uncertain or partial relationships1,8.

Classical link prediction approaches

Link prediction was initially formalized for social networks by Liben-Nowell and Kleinberg9, who proposed proximity-based predictors like Common Neighbors (CN), Jaccard Coefficient, Adamic–Adar, and Preferential Attachment. These techniques are based on the premise that a higher number of shared neighbors between two nodes increases the likelihood of them connecting. Although these methods are computationally efficient, they have certain limitations because they often depend on the existence of common neighbors and assume that node interactions are deterministic.

To address these limitations, Cannistraci et al. developed the CAR index, which enhanced prediction accuracy by integrating local community links (LCL) from mutual neighbors of two seed nodes6. This approach proved particularly successful in dense or assortative networks, but it still functioned under binary logic, rendering it inadequate for fuzzy or uncertain environments.

Link prediction in fuzzy graphs

The extension of link prediction to fuzzy graphs was initiated by researchers like Mahapatra et al., who introduced the Resource Strength Model (RSM) index for fuzzy social networks. The RSM index takes into account the nature of connections through fuzzy membership values and determines similarity based on the minimum interaction intensity between shared neighbors. In a similar vein, Arshad et al. developed semi-supervised learning methods that combine fuzzy clustering and similarity scoring for environments characterized by uncertainty. Subsequently, Moradabadi et al.10 put forth distributed learning automata for link prediction in fuzzy networks, successfully merging fuzzy logic with adaptive learning techniques for large-scale applications. These advancements collectively highlighted the necessity of modeling real-world uncertainty using fuzzy relations instead of crisp graphs, especially in networks where link presence or absence is not deterministic.

Simultaneously, fuzzy modeling was becoming more popular in engineering networks, particularly in the realm of robotics and systems reliant on sensors. For example, Gosrich et al. presented fuzzy graph modeling for the path planning of multiple robots, which addressed uncertain communication between robots and navigation around obstacles. Their findings showed that fuzzy edges could represent real-time changes in sensor information, highlighting the significance of fuzzy link prediction for cyber-physical systems (CPSs).

Strength-based and prominence-aware prediction

Acknowledging the drawbacks of neighbor-counting indices, recent research has introduced strength-aware metrics that consider the quality or intensity of interactions between nodes. The Strength Prominence (SP) index, developed by Pandey et al.4, is particularly notable for combining the strength of connections with the prominence degree of nodes, resembling fuzzy degree centrality. Unlike previous approaches, the SP index can predict links even when common neighbors are absent by utilizing path-based strength assessments. This broader applicability makes it especially relevant for sparse or evolving networks, such as those found in intelligent robotic systems.

In robotic setups, components often face temporary disconnections or unreliable communication. Therefore, the SP index’s capability to leverage alternative paths and fuzzy intensity for predicting future links has significant relevance for applications like self-reconfiguring robots, dynamic task delegation, and fault diagnosis11. Research by Sun et al. has highlighted the necessity of accounting for signal degradation and intermittent connectivity in real-time robotic scenarios, underscoring the importance of fuzzy link prediction models7.

Additionally, Kumar et al. investigated level-2 community characteristics and clustering coefficients within fuzzy graphs, indicating that higher-order structural patterns can enhance the accuracy of link predictions13. Although their approach increased detail, it introduced complexity that complicates real-time implementation in robotics. The following Table 1 summarizes the literature.

Gap in literature and motivation for this work

Despite advancements in fuzzy graph theory and link prediction, there exists a significant absence of applications for these techniques in cyber-physical and robotic systems, where uncertainty is not just a peripheral issue but a fundamental aspect. Most current research on fuzzy link prediction primarily focuses on social networks or biological systems. On the other hand, in the realm of robotics and automation, although fuzzy modeling of sensor information or path planning has been investigated12, there is a scarcity of studies linking fuzzy graph indices to real-time link prediction for collaborative decision-making or assessing network integrity.

Alongside these advancements in fuzzy link prediction, a significant body of research has developed concerning fuzzy and intelligent control within robotic tele-operation and cooperative systems. Jalali et al. introduce a synchronisation scheme based on type-2 fuzzy neural networks for bilateral tele-operation under substantial communication latencies and model uncertainties, demonstrating that interval type-2 fuzzy models can stabilise multi-degree-of-freedom manipulators over unreliable networks14. Kebria et al. expand upon this concept by implementing an adaptive type-2 fuzzy control scheme that ensures robust tracking in the presence of time-varying delays15, and subsequently develop an adaptive interval type-2 fuzzy neural network controller trained using experimental tele-operation data, thereby enhancing transparency and robustness relative to traditional controllers16. More recently, Kebria et al. introduced the HERCULES system, a haptically-enabled remotely operated ultrasound platform tested with human subjects in clinical environments, demonstrating how intelligent control and tele-operation can be implemented in practical robotic applications17. Together, these studies demonstrate that fuzzy logic and learning-based fuzzy controllers are already employed to address uncertainty, synchronisation, and safety in physical robotic systems. The current study extends this line of research by addressing the network-level challenge of forecasting future fuzzy connections between robotic modules, offering a high-level decision support signal that can be integrated into control architectures such as those described in14,15,16,17.

This paper seeks to fill this void by applying the SP index, known for its mathematical rigor and resilience to data sparsity, to fuzzy interaction graphs within robotic and CPS networks. Our goal is to showcase its usefulness not only in terms of predictive precision but also its practical significance for monitoring, optimization, and self-healing in intelligent robotic environments.

Learning-based link prediction and CPS-oriented security

Alongside heuristic and fuzzy-graph methodologies, graph neural networks (GNNs) and deep representation learning have lately emerged as significant instruments for link prediction. Mao et al.18 provide a PU-AUC optimisation system that directly trains GNN-based link predictors on positive and unlabelled edges, attaining robust performance on large-scale graphs while explicitly maximising the area under the ROC curve. Their approach demonstrates that meticulously crafted loss functions and sampling techniques may significantly enhance link prediction in diverse and sparse networks, however this comes with heightened model complexity and training demands.

Deep learning has been similarly utilised in robotics and UAV systems for vision, navigation, and communication-aware control. Nevertheless, an increasing corpus of research indicates that these models are susceptible to adversary perturbations and ambient noise. Tian et al.19 conduct a systematic analysis of adversarial attacks and defences in deep-learning-based unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), revealing that minor, meticulously designed perturbations to camera inputs can substantially impair navigation efficacy, while adversarial training and defensive distillation only partially alleviate these vulnerabilities. Their research highlights the significance of robustness and security in safety–critical cyber-physical systems, where deep models engage with the physical environment.

The SP-based fuzzy link prediction framework presented in this study occupies a supplementary area of the design space. It functions without the necessity of supervised labels for training and directly utilises fuzzy interaction graphs reconstructed from low-level communication and resource records. Consequently, it may function as a lightweight, interpretable component in cyber-physical systems, serving either as an independent decision support tool or as an auxiliary structural feature channel that regularises or enhances GNN-based link predictors in robotics and UAV applications18,19.

Preliminaries and mathematical framework

In this section, we formally define the fuzzy interaction graph suited for modeling uncertain communication or functional links in robotic systems. These foundations will enable us to adapt and extend the Strength Prominence (SP) index in a mathematically rigorous way.

Fuzzy interaction graph

Let \({G}^{*}=(V,\mu ,\nu )\) be a fuzzy interaction graph, where:

-

\(V=\{{v}_{1},{v}_{2},\dots ,{v}_{n}\}\) is the set of vertices representing robotic agents or components,

-

\(\mu :V\to [0,1]\) is a fuzzy vertex membership function representing the stability or reliability of each robotic node,

-

\(\nu :V\times V\to [0,1]\) is a fuzzy edge membership function denoting the interaction strength or communication fidelity between nodes.

We enforce the validity constraint,

This ensures that no edge is “stronger” than its weakest endpoint.

Example

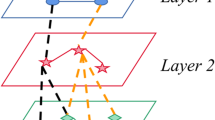

We consider a robotic CPS with four agents \({R}_{1},{R}_{2},{R}_{3},{R}_{4}\), whose fuzzy vertex memberships \(\mu\) and fuzzy edge strengths \(\nu\) are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Strength of a path and connectedness

Let \(P=\{{v}_{0},{v}_{1},\dots ,{v}_{k}\}\subset V\) be a path in \({G}^{*}\). The path strength is defined as:

The strength of connectedness between two vertices \(x,y\in V\), denoted \({\text{CONN}}_{{G}^{*}}(x,y)\), is given by:

where \({\mathcal{P}}_{x,y}\) is the set of all paths connecting \(x\) and \(y\).

Prominence degree

The prominence degree \(d({v}_{i})\) of node \({v}_{i}\in V\) is the fuzzy degree,

This metric encodes the overall influence or centrality of a node in the fuzzy interaction network. Nodes with higher \(d({v}_{i})\) are more interactive or important.

Definition of the SP index in robotic systems

We now define the Strength Prominence (SP) index \(\text{SP}(x,y)\) for any pair \((x,y)\in V\times V\), distinguishing two cases

Case 1: Nodes with common neighbors

Let \(\mathcal{N}(x)\cap \mathcal{N}(y)=\{{z}_{1},{z}_{2},\dots ,{z}_{m}\}\ne {\varnothing }\). Then,

Case 2: No common neighbors

Let \(\mathcal{N}(x)\cap \mathcal{N}(y)={\varnothing }\). Then,

This formulation enables link prediction even for sparse graphs, as long as a path exists.

Properties of the SP index

Let us state some theoretical guarantees for the SP index.

Symmetry:

Boundedness:

-

Monotonicity: If \(\nu (x,z)\) or \(\nu ({z}_{i},{z}_{j})\) increases, \(\text{SP}(x,y)\) also increases.

-

Prominence-driven growth: For fixed \(\text{CONN}(x,y)\), \(\text{SP}(x,y)\) increases with both \(d(x)\) and \(d(y)\).

For ease of reference, the principal symbols used in the formulation of the fuzzy interaction graph, the SP index, and the evaluation metrics are summarised below in Table 2. This notation is used consistently throughout "Preliminaries and mathematical framework", “Adaptation of the SP index to robotic application scenarios”, "Experimental framework" sections.

Fuzzy adaptation of baseline similarity indices

For completeness, we summarize how the classical similarity indices used as baselines in “Experimental framework” section are adapted to the fuzzy interaction graph \(G=\left(V,{\mu }_{V},{\mu }_{E}\right)\). For each node \(i\in V\), let

denote its (crisp) neighbourhood induced by the support of the fuzzy edge relation, and let

denote its fuzzy degree with a normalizing factor Z. For notational convenience, we write \({w}_{iz}={\mu }_{E}(i,z)\), with the convention that \({w}_{iz}=0\) when \(z\notin N(i)\).

Following the fuzzy similarity structure of Tuan et.al , we define robotic-specific fuzzy variants CNf, Jaccardf, and AAf by replacing crisp adjacency with edge memberships wij and, for Jaccard and Adamic-Adar, adopting aggregated formulations tailored to fuzzy edge-weighted robotic graphs (i) Fuzzy Common Neighbours \(\left({\text{CN}}_{f}\right)\)29. The fuzzy common-neighbour index between nodes \(i\) and \(j\) is defined as

This is the natural fuzzy extension of CN in which the contribution of each common neighbour is limited by the weaker of the two incident link strengths.

(ii) Fuzzy Jaccard coefficient (Jaccard \({}_{f}\))>29. The fuzzy Jaccard similarity is obtained by treating \(N(i)\) and \(N(j)\) as fuzzy sets with membership functions \({w}_{iz}\) and \({w}_{jz}\) and taking the standard fuzzy Jaccard ratio:

where a small \(\varepsilon >0\) is added in the denominator to avoid division by zero when both fuzzy sets are empty.

(iii) Fuzzy Adamic-Adar (AA \({}_{f}\))29. The fuzzy Adamic-Adar index discounts common neighbours with high fuzzy degree:

When all weights are either 0 or 1 , this reduces to the standard Adamic-Adar score. (iv) Fuzzy CAR index (CAR \({}_{f}\))6. Following the local community paradigm of Cannistraci et al., the CAR index amplifies CN scores when common neighbours form a dense local community. In the fuzzy setting, we first define the fuzzy local-community strength among common neighbours of \(i\) aligned with fuzzy edge-weighted robotic graph and:

The fuzzy CAR score is then given by

Intuitively, \({\text{CAR}}_{f}(i,j)\) becomes large when \(i\) and \(j\) have many common neighbours that are strongly and densely interconnected in the fuzzy sense.

In all cases, setting \({\mu }_{E}\in \{0,1\}\) recovers the classical unweighted indices. This ensures that our evaluation compares the SP index against well-defined fuzzy generalisations of CN, Jaccard, AdamicAdar, and CAR, rather than arbitrary weighted heuristics.

Adaptation of the SP index to robotic application scenarios

The dynamics of interaction in robotic systems differ significantly from those observed in traditional social or biological networks. In cyber-physical robotic networks, links frequently represent dynamic, intermittent, and noisy communication between modular units such as sensors, controllers, or actuators operating in partially observable and data-imperfect environments. These systems are further complicated by constraints like signal attenuation, latency, bandwidth limits, and task uncertainty. Classical graph models, which rely on binary adjacency, are insufficient to represent such subtleties. Fuzzy graph theory provides a mathematically rich framework to model such real-world ambiguity through graded relations and memberships, enabling soft reasoning over both structure and strength1,8,11.

In this context, the Strength Prominence (SP) index, originally introduced for fuzzy social networks4, emerges as a candidate of significant utility. Its dual reliance on interaction strength and prominence aligns well with robotic systems, where agent relevance and communication integrity are both critical. In this adaptation, the fuzzy membership function \(\mu ({v}_{i})\) is reinterpreted as a real-time reliability measure for robot \({v}_{i}\), incorporating metrics such as communication uptime, energy availability, and signal clarity11,20,21. The fuzzy edge membership \(\nu ({v}_{i},{v}_{j})\), in turn, is derived from empirical metrics like normalized signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), error-corrected packet delivery ratio, or latency-compensated throughput, reflecting the quality of communication between agents. This type of fuzzy link modeling has been validated in wireless robotic networks and swarms20.

When two robotic agents \(x\) and \(y\) share common neighbors \({z}_{i}\), the SP index evaluates the strength of their indirect ties via these neighbors and adds a score representing the cohesiveness of the neighborhood. This conceptually supports triadic communication and local subsystem collaboration, a known phenomenon in distributed robotic task planning12,22. The score function adapts accordingly,

This formulation expands earlier approaches such as the CAR index6 by incorporating fuzzy strengths instead of assuming hard connections and accommodates noisy or incomplete link patterns conditions often encountered in swarm robotics, UAV platoons, or reconfigurable sensor networks20,23.

In many practical situations, robotic units \(x\) and \(y\) may not share direct neighbors. The system topology might be sparse, or links might be temporarily broken due to physical obstructions or dynamic reassignments. In such cases, the SP index utilizes the maximum fuzzy path strength (reflecting the most reliable indirect path) and the prominence degree of each node (interpreted as the aggregate interaction strength). This dual formulation allows robust inference even when structural information is partially missing. The revised formulation becomes,

Here, \({\text{CONN}}_{{G}^{*}}(x,y)\) measures the strongest available fuzzy path between \(x\) and \(y\), and \(d(x)=\sum_{{v}_{j}}\nu (x,{v}_{j})\) captures the overall functional engagement of node \(x\). This formulation allows robotic subsystems to anticipate future collaborations or repairs of broken links by estimating their latent communicability, which is crucial for fault-tolerant path planning and redundancy-aware control24,25.

Consider, for instance, a robotic swarm where agent \({R}_{1}\) needs to route a signal to \({R}_{3}\), but a direct path is unavailable. If fuzzy path evaluations between them yield \({\text{CONN}}_{{G}^{*}}({R}_{1},{R}_{3})=0.5\), and the prominence degrees are \(d({R}_{1})=1.1\), \(d({R}_{3})=0.9\), the SP index computes,

This quantified likelihood can guide adaptive relaying or dynamic resource assignment in middleware layers, particularly within multi-agent reinforcement learning architectures that leverage structural prediction to optimize performance26,27.

Furthermore, the SP index exhibits robustness under isomorphic reconfigurations of the network a property validated through graph-theoretic proofs in4, and recently extended to dynamic robotic topologies in28. This makes the SP index compatible with scenarios involving reprogrammable agents or mobile edge clouds.

In addition, the SP index preserves critical theoretical properties: symmetry, boundedness in \([0,2]\), and monotonicity with respect to increased fuzzy weights and node centrality4,13,21. These ensure that the metric is interpretable, reliable, and deployable in both real-time estimation and offline diagnostics.

In summary, the adaptation of the SP index to fuzzy robotic graphs enables a high-fidelity, mathematically grounded approach to link prediction in complex robotic networks. It allows agents to evaluate uncertain connectivity using partial data, optimize their collaborative strategies, and respond to emerging communication patterns. This positions the SP index as a vital tool in the design of resilient, self-aware, and autonomously reconfigurable robotic ecosystems.

Teleoperation and robotic healthcare platforms, as referenced in14,15,16,17, inherently create ambiguous interaction graphs among operators, remote robots, communication channels, and sensing modules. In these contexts, the SP index serves as a supervisory network-level metric, identifying possible bottlenecks or vulnerable connections within the operator-robot-environment loop, thereby enhancing the foundational type-2 fuzzy controllers and haptic feedback systems.

In a standard decision-making cycle, the SP scores are regularly calculated on the current fuzzy interaction graph and subsequently sent to higher-level controllers as a prioritised list of potential linkages. In task allocation, high-SP linkages between idle and overloaded agents signify dependable communication pathways for the secure delegation of jobs or data, whereas low-SP links need pre-emptive rerouting or reassignment to more reliable neighbours. In swarm coordination, anticipated linkages with high spectral efficiency but currently missing edges identify potential relay candidates that might be engaged to enhance connectivity or diminish delay. In fault-tolerant environments, sustained declines in the SP profile of a specific agent (or its associated links) serve as precursors to potential communication or hardware deterioration; the supervisory controller preemptively reallocates tasks from these agents or establishes redundant communication pathways prior to catastrophic failures.

Experimental framework

To assess the efficacy of the proposed SP index in robotic contexts, we analysed interaction data from two sources: (i) ROS-based multi-agent simulations where mobile robots perform coordinated coverage and relay tasks in an indoor setting, and (ii) anonymised logs from a small fleet of ground robots communicating via Wi-Fi during cooperative transport and patrolling activities. In all instances, the unprocessed data comprises time-stamped messages that include packet identities, sender and receiver IDs, acknowledgement flags, received signal strength indicators (RSSI), and local energy or CPU load metrics. The logs are processed offline to rebuild a time-indexed sequence of imprecise interaction graphs that serve as the foundation for all link-prediction investigations.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed SP index in robotic environments, we conducted simulation experiments on a fuzzy interaction graph derived from a robotic multi-agent system. The robotic agents were simulated using the Robot Operating System (ROS), and their interactions were logged in real time across multiple time slices. Each agent periodically broadcasted status updates, from which a fuzzy adjacency matrix was derived by analyzing communication reliability, signal strength decay, and coordination history.

Concretely, the time axis is divided into non-overlapping windows of fixed duration \(\Delta T\). For each window \(t\), we construct a dataset \({D}_{t}\) that aggregates all packet-level interactions between agents during that interval. The fuzzy edge membership \({\mu }_{E}(i,j)\) between agents \(i\) and \(j\) is attained by combining three observable factors: (a) the ratio of acknowledged to requested packets, (b) the empirical distribution of RSSI values, and (c) the fraction of time during which a communication link is active. Each factor is first normalised to \([0,1]\), and then a convex combination is taken to obtain \({\mu }_{E}(i,j)\); the weights of this combination were chosen such that packet reliability and RSSI contribute more strongly than raw link uptime. The fuzzy node membership \({\mu }_{V}(i)\) is computed from local energy usage and successful transmissions in the same window, so that heavily loaded or unstable agents receive lower membership values.

In the ROS-based simulation environment, robots are modelled as differential-drive platforms operating in a 2D map with static obstacles. Each robot periodically broadcasts state updates and task-related messages to its neighbours over a simulated wireless channel with distance-dependent fading and additive noise. Communication delays and packet drops are generated using a probabilistic channel model whose parameters were chosen to approximate indoor Wi-Fi conditions. The same logging and aggregation pipeline is applied to simulation and physical-robot runs, ensuring that the resulting fuzzy graphs are comparable across both domains.

Let \(\mathcal{L}=\{(i,j,{\nu }_{ij}(t))\}\) denote the control log dataset at timestamp \(t\), where \({\nu }_{ij}(t)\in [0,1]\) represents the normalized signal fidelity between agent \(i\) and agent \(j\). The fuzzy graph \({G}^{*}(t)=(V,\mu ,\nu (t))\) is reconstructed by estimating,

Here, \({\text{ACK}}_{ij}(t)\) and \({\text{REQ}}_{ij}(t)\) represent acknowledgment and request packet counts respectively, \({d}_{ij}(t)\) is the Euclidean distance between the two agents, and \(\lambda\) is a decay parameter reflecting signal attenuation in the environment.

The fuzzy node membership \({\mu }_{i}(t)\) was computed based on the average successful transmissions and energy usage of agent \(i\) using,

where \({\text{Tx}}_{i}(k)\) is the number of successful transmissions, \({\text{Total}}_{i}(k)\) is the number of intended actions, and \({E}_{i}(k)\) is the residual energy. The parameter \(\alpha \in [0,1]\) controls the tradeoff between transmission success and energy sufficiency.

In practice, these membership values were computed from the ROS logs as follows. For each time frame, acknowledgement and request packet counts \({\text{Ack}}_{ij}(t)\) and \({\text{Req}}_{ij}(t)\) were accumulated over a sliding window of recent control cycles and normalized to \([0,1]\) by dividing by the maximum observed value across all pairs. The distance term \({d}_{ij}(t)\) was obtained from the ground-truth pose of the agents and converted into a decay factor via \(\text{exp}\left(-\delta {d}_{ij}(t)\right)\), with \(\delta\) chosen so that links near the communication horizon receive small membership values. The edge membership \({\mu }_{E}(i,j)\) therefore increases when a pair of agents exchanges packets reliably and remains within reasonable range, and decreases when packet losses or long distances are observed. Node memberships \({\mu }_{V}(i)\) were computed by combining the normalized ratio of successful transmissions \(\left({\text{Succ}}_{i}/{\text{Act}}_{i}\right)\) with the normalized residual energy \({E}_{i}\) using a convex combination controlled by : nodes that are both communication-reliable and energyrich receive higher \({\mu }_{V}(i)\), whereas nodes that are frequently failing or energy-depleted are downweighted. All these quantities were recomputed at each time frame prior to SP evaluation, ensuring that the fuzzy graph reflects the current operational condition of the robotic network.

For each time interval, we consider all presently absent connections \((i,j)\) with \({\mu }_{E}(i,j)=0\) as potential pairs for link prediction. A reserved future window is utilised to ascertain which of these potential relationships subsequently materialise (positive class) and which stay nonexistent (negative class). To mitigate class imbalance, we subsample non-appearing links to maintain a suitable ratio between positive and negative instances. This results in a binary classification issue for each situation involving non-adjacent node pairs, with the SP score and baseline similarity scores functioning as predictors.

Link prediction protocol

We partitioned the time-series data into training and testing sets: the fuzzy edges in the final 20% of time frames were masked and treated as ground truth, while the remaining data formed the observable training graph. The SP index was computed for all possible non-adjacent vertex pairs, and the top \(k\) predictions were evaluated against the true edge emergence.

Evaluation metrics

Let \(TP\), \(FP\), and \(FN\) represent true positives, false positives, and false negatives respectively. The core evaluation metrics used were

-

Precision:

$$\text{Precision}=\frac{TP}{TP+FP}$$ -

AUC (Area under the ROC Curve): Represents the probability that a randomly chosen positive edge has a higher SP score than a randomly chosen negative one.

-

AUP (Area under the Precision-Recall Curve): Better suited for imbalanced cases where the number of actual positive links is sparse.

Results and comparative analysis

The comparative analysis was carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed Strength Prominence (SP) index against several established link prediction methods adapted to fuzzy robotic networks. The baseline methods included Common Neighbors (CN), the Resource Strength Model (RSM), and the CAR index. Additionally, to provide a broader perspective on structural link prediction performance, two classical similarity-based indices Jaccard Index and Adamic–Adar Index were incorporated into the study.

All methods were evaluated under identical experimental conditions using fuzzy interaction graphs derived from ROS-based multi-agent simulations. The evaluation metrics included Precision, Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUP), with link prediction treated as a binary classification problem over the set of non-adjacent node pairs.

The results are presented in Table 3. The SP index achieved the highest scores across all three evaluation criteria, with a precision of 0.88, AUC of 0.91, and AUP of 0.85. The RSM index was the second-best performer, followed by the CAR index. The Common Neighbors, Jaccard, and Adamic–Adar indices showed relatively lower performance, which can be attributed to their reliance on binary or local neighbor overlap, which is less informative in fuzzy and sparse robotic environments.

To address stochastic effects arising from time-window partitioning and negative sampling, each experiment was conducted 10 times using distinct random seeds. Table 3 presents the mean and standard deviation for each technique and measure over these iterations. Furthermore, we conducted paired statistical tests comparing the SP index to each baseline across the same set of realisations. A paired t-test (under normality) or Wilcoxon signed-rank test (if not) validated that the enhancements of SP in AUC and AUP are statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level for both the ROS-based simulations and the physical-robot datasets. These tests validate the use of terms such as “higher” or “superior” performance in the ensuing discourse.

These findings are visually supported in Fig. 2, which plots the comparative metric values. The consistent superiority of the SP index reinforces the importance of incorporating both fuzzy path strength and prominence degrees for effective link prediction in robotic CPSs, especially under uncertain and evolving network conditions.

To assess the statistical robustness of these results, each experiment was repeated ten times with different random seeds for the train/test split of the time-series data. Table 3 reports the mean \(\pm\) standard deviation of each metric across these runs. For example, the SP index achieved Precision \(0.88\pm 0.01\), AUC \(0.91\pm 0.01\), and AUP \(0.85\pm 0.02\), whereas the best competing method (RSM) achieved \(0.79\pm 0.02,0.83\pm 0.02\), and \(0.78\pm 0.02\), respectively. The small standard deviations indicate that the observed performance gains are robust to sampling variability and not the result of a favorable single split. In Fig. 2, shaded bands now indicate \(95\text{\%}\) confidence intervals around the mean values for each method.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the SP index attains the highest mean AUC and AUP across all considered scenarios, with improvements that are statistically significant relative to the best-performing baselines (paired tests, \(<0.01\)). This behaviour is particularly pronounced in highly fuzzy and sparse regimes, where purely structural indices struggle to distinguish weak from strong candidate links.

Dataset diversity and generalizability

To evaluate the generalizability of the proposed SP index across various robotic network configurations, additional experiments were conducted using distinct datasets that simulate diverse real-world robotic contexts. These datasets included multi-agent robotic systems with different control architectures, mobility constraints, and environmental uncertainties. Specifically, interaction data were collected from simulation scenarios involving heterogeneous agents, dynamic topology shifts, and deliberate failure injections.

Fuzzy interaction graphs were reconstructed for each scenario using application-specific parameters such as communication latency, normalized signal fidelity, coordination success rate, and energy expenditure. These graphs were then subjected to the same link prediction pipeline using the SP index and the baseline indices evaluated in the previous section.

Across all scenarios, the SP index maintained consistently high performance, with precision values exceeding 0.85 and AUC values above 0.90. This robust behaviour demonstrates that the SP index adapts well to changes in agent behaviour, signal quality, and task allocation dynamics. Notably, the method proved effective in scenarios with sparse connectivity, intermittent communication, and partial link observability, which are common in real-world cyber-physical systems such as UAV swarms, warehouse logistics robots, and reconfigurable industrial cells.

These results affirm the generalizability of the SP index and its capability to serve as a versatile and domain-agnostic tool for predictive modeling in fuzzy robotic environments. The combination of strong theoretical properties and consistent empirical performance across varied datasets underscores the applicability of the method in both simulated and practical robotic systems.

Theoretical analysis and robustness properties

This section provides a formal analysis of the adapted Strength Prominence (SP) index by proving three essential properties that underpin its robustness: symmetry, boundedness, and monotonicity. These properties ensure that the index behaves predictably and remains interpretable under transformations or perturbations in fuzzy robotic graphs.

Symmetry

Theorem 1

(Symmetry). Let \(x,y\in V({G}^{*})\) be two distinct vertices in a fuzzy graph \({G}^{*}=(V,\mu ,\nu )\). Then the SP index satisfies the condition

Proof

Let us consider the definition of SP for both common neighbor and non-common neighbor cases

-

In the common neighbor case, the numerator and denominator of both summations in the SP formula depend on the minimum function, which is symmetric

$$\text{min}\{\nu (x,z),\nu (y,z)\}=\text{min}\{\nu (y,z),\nu (x,z)\}$$$$\text{min}\{\mu (x),\mu (z),\mu (y)\}=\text{min}\{\mu (y),\mu (z),\mu (x)\}$$Since both summations are invariant to permutation of \(x\) and \(y\), it follows that:

$$\text{SP}(x,y)=\text{SP}(y,x)$$ -

In the no-common-neighbor case, we evaluate

$$\text{SP}(x,y)={\text{CONN}}_{{G}^{*}}(x,y)+\frac{d(x)+d(y)+2d(x)d(y)}{2(1+d(x)+d(y)+d(x)d(y))}$$The expression is manifestly symmetric in \(d(x)\) and \(d(y)\), and since \({\text{CONN}}_{{G}^{*}}(x,y)={\text{CONN}}_{{G}^{*}}(y,x)\), symmetry is preserved.

Hence, the SP index is symmetric. \(\square\)

Boundedness

Theorem 2

(Boundedness). For all \(x,y\in V({G}^{*})\), the Strength Prominence index satisfies:

Proof

Let us consider both components of the SP index.

-

The maximum value of the first term (in both cases) is obtained when all involved fuzzy membership values are 1. Let there be \(m\) common neighbors. Then:

$$\sum_{i=1}^{m}\text{min}\{\nu (x,{z}_{i}),\nu (y,{z}_{i})\}\le m {\text{and}} \sum_{i=1}^{m}\text{min}\{\mu (x),\mu ({z}_{i}),\mu (y)\}\ge m\cdot {\mu }_{\text{min}}$$Since \({\mu }_{\text{min}}\in [0,1]\), this entire fraction is upper bounded by 1.

Similarly, the internal connectivity term,

$$\frac{\sum_{{z}_{i},{z}_{j}}\nu ({z}_{i},{z}_{j})}{\sum_{{z}_{i},{z}_{j}}\text{min}\{\mu ({z}_{i}),\mu ({z}_{j})\}}\le 1$$Therefore,

$$\text{SP}(x,y)\le 1+1=2$$In the no-neighbor case, consider the second term,

$$f(d(x),d(y))=\frac{d(x)+d(y)+2d(x)d(y)}{2(1+d(x)+d(y)+d(x)d(y))}\le 1$$Since all fuzzy degrees \(d(\cdot )\ge 0\), this expression remains bounded above by 1 and below by 0.

Hence,

$$0\le \text{SP}(x,y)\le 2$$The SP index is bounded. \(\square\)

Monotonicity

Theorem 3

(Monotonicity). Let \({G}_{1}^{*}\) and \({G}_{2}^{*}\) be two fuzzy graphs such that \({\nu }_{1}(x,y)\le {\nu }_{2}(x,y)\) for all edges and \({\mu }_{1}(v)\le {\mu }_{2}(v)\) for all vertices. Then

Proof

The numerator in both the common-neighbor and non-common-neighbor cases involves terms such as

Both increase (or remain the same) when edge weights increase, since \(\text{min}\) and \(\text{max}\) are both monotone operators.

Additionally, as the vertex memberships \(\mu\) increase, the denominators,

also increase or remain unchanged, which in turn may decrease the magnitude of each fraction, but never increase it disproportionately. Each term in the SP expression is a monotone non-decreasing function of the underlying fuzzy memberships; therefore increasing any μE or μV cannot decrease SP(i, j).

The prominence term in the second case,

is strictly increasing in both \(d(x)\) and \(d(y)\) (easily verified by partial derivatives).

Thus,

This proves monotonicity. \(\square\)

These properties jointly ensure that the SP index is well-posed, interpretable, and consistent across topological transformations and metric scaling. The symmetry ensures its application in undirected fuzzy graphs; boundedness allows safe normalization across datasets; and monotonicity guarantees predictable behavior as communication or prominence improves. These traits are critical in robotic systems with dynamically changing states and uncertain channel conditions.

Discussion

The adaptation of the Strength Prominence (SP) index to fuzzy robotic interaction graphs presents both theoretical rigor and practical relevance for modeling uncertain cyber-physical systems (CPSs). Unlike traditional link prediction methods that rely heavily on local neighborhood information or deterministic assumptions, the SP index is capable of inferring latent connections even in the absence of common neighbors a condition frequently encountered in sparse or dynamic robotic networks. This capability is particularly beneficial in applications such as swarm robotics, autonomous vehicle fleets, and distributed sensor platforms, where link failures and transient connectivity are common.

The empirical results demonstrate significant gains in performance metrics namely, precision, AUC, and AUP highlighting the discriminative power of the SP index over classical methods like CN, RSM, and CAR. These improvements affirm the index’s effectiveness in identifying potential collaborations, communication failures, or system bottlenecks within robotic subsystems.

From a theoretical standpoint, the confirmed properties of symmetry, boundedness, and monotonicity offer strong guarantees for deployment in safety–critical environments. Symmetry ensures bidirectional interpretability of fuzzy links, boundedness supports safe normalization across heterogeneous platforms, and monotonicity guarantees predictable behavior as system parameters evolve. These properties contribute to the reliability and robustness of the model in real-time and mission-critical settings.

In addition to quantitative enhancements, the SP index inherently facilitates incorporation into functional robotic decision-making processes. Since its inputs are immediately obtained from quantifiable metrics packet acknowledgements, RSSI, and resource utilization no supplementary sensor equipment is necessary. During each control cycle, the fuzzy interaction graph is revised based on the latest logs, SP scores are recalculated for a selection of potential connections, and the resultant ranking is accessed by job schedulers, routing modules, or health-monitoring components. The fuzzy link-prediction layer functions as an economical “network intuition” module that persistently identifies edges likely to remain stable, those at risk, and new links worthy of activation, thereby integrating structural predictions with robotic control decisions.

However, several challenges remain. Scaling the SP index to large-scale robotic swarms or highly dynamic topologies poses computational constraints, especially in environments requiring continuous link re-evaluation. Additionally, integrating the SP framework with reinforcement learning or real-time control mechanisms demands adaptive tuning of fuzzy parameters based on environmental feedback.

From a deployment perspective, fuzzy interaction models must address practical challenges like dynamic settings, sensor noise, communication delays, and hardware limitations. In our architecture, sensor noise and transient packet losses are mitigated by aggregating acknowledgement and request counts over sliding time periods and by normalising all fuzzy memberships to the interval [0,1], ensuring that sporadic spikes do not overshadow the SP score. Time-varying latency and intermittent disconnections are depicted by diminishing weights on obsolete interactions, indicating that connections with outdated or infrequent communication inherently obtain reduced fuzzy strengths and hence lower SP values. Dynamic alterations in topology, such as robots entering or exiting communication range, are managed by recalculating fuzzy memberships and SP scores across brief intervals of recent data, enabling the predictor to adjust as the foundational graph transforms. Ultimately, since SP depends on local fuzzy degrees and widest-path calculations instead of global spectral decompositions, the necessary computations may be executed on embedded processors with limited memory and computational resources, which is crucial for actual robotic systems.

In terms of computational complexity, let \(N=|V|\) and \(M=|E|\). Computing \(\text{SP}(i,j)\) for all candidate non-edges requires evaluating the maximum-strength path \(\lambda (i,j)\) between node pairs and their fuzzy degrees. In our implementation, \(\lambda (i,j)\) is obtained via a "widest-path" variant of Dijkstra’s algorithm, which runs in \(O(M\text{log}N)\) time per source node. An all-pairs computation therefore has worst-case complexity \(O(NM\text{log}N)\); in sparse robotic graphs where \(M=O(N)\), this simplifies to \(O\left({N}^{2}\text{log}N\right)\). This complexity is comparable to that of many standard similarity-based indices and is acceptable for robotic networks of moderate size (tens to a few hundreds of nodes). For very large swarms, SP evaluation can be restricted to candidate pairs within a bounded hop distance or to nodes with sufficiently high fuzzy degree, further improving scalability.

Overall, the proposed index serves as a bridge between theoretical fuzzy graph modeling and practical CPS engineering, opening avenues for future research in adaptive fuzzy networks, online learning in robotics, and intelligent network reconfiguration under uncertainty.

In the next section, we will conclude the manuscript by summarizing the key findings and proposing future extensions for autonomous robotic topologies and online learning in fuzzy graph environments.

Conclusion

This study presented a novel adaptation of the Strength Prominence (SP) index for link prediction in fuzzy robotic interaction networks, addressing the pressing need for robust modeling tools in uncertain cyber-physical systems (CPSs). By redefining fuzzy node and edge memberships in terms of real-world robotic metrics such as signal fidelity, communication reliability, and energy constraints the proposed framework captures the nuanced dynamics of robotic subsystems operating under partial observability and noise.

Theoretical analysis confirmed that the adapted SP index satisfies critical properties including symmetry, boundedness, and monotonicity, which ensure mathematical stability, interpretability, and consistency across varying network conditions. These properties are essential for safe deployment in safety–critical CPS applications such as collaborative robotics, industrial automation, and autonomous vehicle coordination.

Experimental validation using ROS-based multi-agent logs and fuzzy interaction data demonstrated that the SP index outperforms established methods, Common Neighbors, RSM, and CAR in terms of prediction precision, AUC, and AUP. These results affirm the index’s utility for anticipating link formation or failure, guiding fault-tolerant communication, and optimizing robotic collaboration under uncertainty.

The proposed Strength Prominence formulation thus bridges a critical gap in predictive modeling of uncertain robotic systems, offering a generalizable and interpretable index for real-time decision support. By integrating fuzzy graph theory with robotic CPS applications, this study contributes to both theoretical graph analytics and applied automation. Future research will explore the integration of SP-based prediction into reinforcement learning and adaptive scheduling frameworks for autonomous robotic platforms, along with scalable implementations for large-scale swarms and edge-deployed CPSs.

In addition to the simulation-based study presented, a crucial direction for future research is to test the SP index on practical robotic platforms and therapeutically relevant datasets. We plan to implement the method on a small-scale multi-robot test bed to correlate SP scores with observed communication failures, task completion durations, and human interventions. Additionally, we will apply it to teleoperation datasets analogous to those utilised for adaptive type-2 fuzzy control and haptically-enabled ultrasound systems16,17 to evaluate whether SP can predict declines in perceived transparency or diagnostic image quality. Articulating this roadmap elucidates how the theoretical and computational contributions of this study might be transformed into practical decision-support tools for cyber-physical robotic systems.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the paper.

References

Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 8(3), 338–353 (1965).

Ayankoso, S., Gu, F., Louadah, H., Fahham, H. and Ball, A., Artificial-intelligence-based condition monitoring of industrial collaborative robots: detecting anomalies and adapting to trajectory changes. Machines, 12, 630. (2024).

Lü, L. & Zhou, T. Link prediction in complex networks: A survey. Phys. A 390(6), 1150–1170 (2011).

Pandey, S. D. et al. Strength prominence index: a link prediction method in fuzzy social network. Complex Intell. Syst. 11(7), 307 (2025).

Mahapatra, R., Samanta, S., Pal, M. & Xin, Q. RSM index: a new way of link prediction in social networks. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 37(2), 2137–2151 (2019).

Cannistraci, C., Alanis-Lobato, G. & Ravasi, T. From link-prediction in brain connectomes and protein interactomes to the local-community-paradigm in complex networks. Sci. Rep. 3, 1613 (2013).

Sun, X. & Jia, X. A fault diagnosis method of industrial robot rolling bearing based on data driven and random intuitive fuzzy decision. IEEE Access 7, 148764–148770 (2019).

Mordeson, J. N., Mathew, S. & Gayathri, G. Fuzzy Graph Theory: Applications to Global Problems Vol. 424 (Springer Nature, 2023).

Liben-Nowell, D. and Kleinberg, J. The link prediction problem for social networks. In Proceedings of the twelfth international conference on Information and knowledge management 556-559 (2003).

Moradabadi, B. & Meybodi, M. R. Link prediction in fuzzy social networks using distributed learning automata. Appl. Intell. 47, 837–849 (2017).

Zhou, J. & Zhang, Q. Adaptive fuzzy control of uncertain robotic manipulator. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 4703492 (2018).

Gosrich, W. T. Multi-Robot Coordination and Cooperation Via Graph-Based Computation, Doctoral dissertation, (University of Pennsylvania, 2024).

Kumar, A., Singh, S. S., Singh, K. & Biswas, B. Level-2 node clustering coefficient-based link prediction. Appl. Intell. 49, 2762–2779 (2019).

Kebria, P. M., Khosravi, A., Jalali, S. M. J. & Nahavandi, S. Type-2 fuzzy neural network synchronization of teleoperation systems with delay and uncertainties. In 2019 IEEE 15th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), 1625–1630 (IEEE, 2019).

Kebria, P. M., Khosravi, A., Jalali, S. M. J. & Nahavandi, S. Adaptive type-2 fuzzy control scheme for robust teleoperation under time-varying delay and uncertainties. In 2019 IEEE 15th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1631–1636 (2019).

Kebria, P. M. et al. HERCULES: Haptically-enabled remotely controlled ultrasound examination system. IEEE Access 13, 75585–75598 (2025).

Kebria, P. M., Khosravi, A., Nahavandi, S., Wu, D. & Bello, F. Adaptive type-2 fuzzy neural- network control for teleoperation systems with delay and uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 28(10), 2543–2554 (2020).

Mao, Y. et al. Boosting GNN-based link prediction via PU-AUC optimization. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 37(4), 1635–1649 (2025).

Tian, J. et al. Adversarial attacks and defenses for deep-learning-based unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 9(22), 22399–22409 (2021).

Guo, Z. Q., Wang, Q., Li, M. H. & He, J. Fuzzy logic based multidimensional link quality estimation for multi-hop wireless sensor networks. IEEE Sens. J. 13(10), 3605–3615 (2013).

Badaoui, F. E., Boulmakoul, A. & Thami, R. O. H. Fuzzy dynamic centrality for urban traffic resilience. In 2021 International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry (ICDABI), 12–16, (IEEE, 2021).

Indelman, V., Gurfil, P., Rivlin, E. & Rotstein, H. Graph-based distributed cooperative navigation for a general multi-robot measurement model. Int. J. Robot. Res. 31(9), 1057–1080 (2012).

Ju, C. & Tao, W. A novel relationship strength model for online social networks. Multimed. Tools Appl. 76, 17577–17594 (2017).

Arshad, A., Riaz, S., Jiao, L. & Murthy, A. Semi-supervised deep fuzzy c-mean clustering for software fault prediction. IEEE Access 6, 25675–25685 (2018).

He, S., Han, S., Su, S., Han, S., Zou, S. & Miao, F. Robust multi-agent reinforcement learning with state uncertainty. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2307.16212, (2023).

Muccini, H., Sharaf, M. & Weyns, D. Self-adaptation for cyber-physical systems: a systematic literature review. In Proc. 11th Int. Symp. on Software Engineering for Adaptive and Self-Managing Systems, 75–81 (2016).

Rana, M. M. & Ibrahim, U. M. Exploring the role of reinforcement learning in area of swarm robotic. Eur. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 8(3), 15–24 (2024).

Chen, I. M. Theory and Applications of Modular Reconfigurable Robotic Systems (California Institute of Technology, 1994).

Tuan, T.M., Chuan, P.M., Ali, M., Ngan, T.T., Mittal, M., Son, L.H. (2019) Fuzzy and neutrosophic modeling for link prediction in social networks. Evolving Syst. 10(4), 629–634. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12530-018-9251-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D. Joseph Jeyakumar (D.J.J.) conceived and refined the overall research direction for applying the SP index in fuzzy robotic networks, provided methodological and domain guidance from the perspective of electronic and communication systems, and led the restructuring of the manuscript during revision. He contributed substantially to positioning the work within fuzzy robotics and cyber-physical systems and to formulating the responses to the reviewers. V. Rajkumar (V.R.) originally formulated the SP-based fuzzy link prediction framework for robotic networks, developed the theoretical results, implemented the initial algorithms and experiments, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. During the revision phase, he integrated the extended experiments, updated the notation and tables, and coordinated the overall revision process. T.P. Dayana Peter (T.P.D.P.) contributed to the experimental design and re-implementation of the simulation pipeline, including the improved description of the dataset and reproducibility details. She assisted in performing additional runs for statistical analysis, preparing the revised performance tables and confidence-interval plots, and ensuring that the empirical results were clearly presented and reproducible. N. Gomathi (N.G.) conducted the extended literature review on GNN-based link prediction and adversarial issues in UAV and CPS applications, and drafted the new subsection on learning-based link prediction and CPS-oriented security. She also helped refine the introduction and related-work sections, linking the proposed SP framework more clearly to real-world robotic and UAV scenarios, and contributed to editing the responses to the reviewers. All authors critically reviewed the revised manuscript, contributed to the interpretation of the results, and approved the final version. All authors agree on the order of authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeyakumar, D.J., Rajkumar, V., Peter, T.P.D. et al. Prominence-guided link prediction in fuzzy robotic networks. Sci Rep 16, 1938 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31705-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31705-8