Abstract

We demonstrate the methodology to investigate particulate matter (PM) emissions from a 7 V/V% hydrotreated vegetable oil-diesel fuel blend (HVO7) compared to conventional diesel (B0) using a state-of-the-art integrated real-time measurement system. The methodology combines photoacoustic spectroscopy (using our custom photoacoustic (PA) instrument incorporating deep UV wavelengths, which is crucial for characterizing the organic matter content of exhaust PM), particle sizing, and thermal treatment to provide comprehensive, in situ characterization of PM across different engine loads and temperatures. We present size distribution and spectral measurements coupled with a thermodenuder that enables volatility-based classification of PM, allowing evaluation of spectral responses with respect to particle size variations and the dynamic black carbon (BC) to organic matter (OM) ratio in exhaust emissions. Our results show that HVO7 reduces particle number concentrations compared to B0, particularly under low-load conditions; however, these reductions gradually diminish at higher engine loads. Spectral measurements show that the HVO-blended fuel produces less black carbon than B0 at all engine loads and lower TD temperatures, with HVO7 exhibiting higher sensitivity to engine operating conditions than B0. The proposed integrated methodology offers a robust framework for real-time PM analysis of fuel emission, and the results demonstrate the potential of HVO blends to mitigate PM emissions, contributing to sustainable fuel development and emission control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

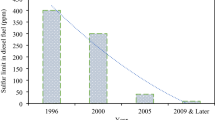

As industrialization extends into rural, urban, suburban, and tribal regions, particulate matter (PM) and gases emitted by reciprocating vehicle engines emission have become prevalent in the atmosphere, contributing to environmental accumulation and significant health risks1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The exhaust PM represents a major source of light-absorbing carbonaceous particulate matter (CPM)8,9. This CPM, consisting of black carbon (BC) and organic matter (OM), plays a critical role in the Earth’s radiative balance and climate system8,9. It remains a significant atmospheric constituent, with substantial uncertainties in its radiative forcing, making it a key focus of contemporary climate research10. The BC exerts a direct net positive radiative forcing by absorbing sunlight11. A recent study estimates that internal combustion engine traffic emissions account for approximately 60% of particle number concentrations in ambient particulate matter12.

The global shift toward sustainable energy solutions has driven the widespread adoption of biodiesel as an alternative to petroleum-based diesel. Current regulatory frameworks primarily support biodiesel use through blending mandates, where blends are categorized based on the volumetric content and feedstock composition of biodiesel13. While these policies have promoted biodiesel adoption, its long-term viability depends on overcoming challenges related to feedstock availability and sustainability. Prioritizing these aspects is essential to ensure that biodiesel remains a viable and environmentally friendly alternative. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) are widely used as a renewable alternative to conventional diesel. However, several limitations, including oxidative aging14, poor storage stability, and unfavorable cold-flow properties, restrict its widespread application15,16.

Hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) has gained attention among alternative blends due to its superior cetane number, reduced engine deposits, and enhanced storage stability. While HVO shares the paraffinic and bio-based nature of biodiesel, it differs fundamentally in production: rather than transesterification with methanol, HVO is produced via hydrotreatment, using hydrogen to remove oxygen from vegetable oils and produce a hydrocarbon-rich fuel17. The advantages of blending HVO with diesel include reduced fuel system clogging, improved regeneration of diesel particulate filters (DPFs), and decreased premature degradation of after-treatment systems18,19. HVO fuel consists of uniform hydrocarbon chains, negligible metal, sulfur, and aromatics, which are present in the diesel fuel. Typically, metal and sulfur are removed during refinement. The higher cetane number makes HVO fuel prone to fast and more complete oxidation, which reduces soot precursors20,21. HVO serves as a drop-in fuel, compatible in neat form or blended at any ratio with petroleum-based diesel, requiring little to no modifications to existing engine systems. Although HVO can be blended up to 100% without compatibility issues, a 7% (v/v) HVO–diesel blend was selected in this study to comply with the EN 590 standard. This facilitates direct comparison with conventional diesel under current regulatory limits, using state-of-the-art, artifact-free (filter-free) instrumentation that enables high-accuracy and high-precision measurements while minimizing uncertainties associated with filter-based analytical methods. Many studies indicate decreased emissions of PM, hydrocarbons, CO, and NOₓ—especially at lower temperatures16,22—while one study reports a slight increase in PM under certain conditions, such as high-load transient cycles in heavy-duty engines without optimization23. Other studies under varying conditions consistently show PM reductions24,25,26,27,28,29. However, previously reported NOx values from HVO fuel emissions exhibit inconsistencies16. These discrepancies underscore the need for further context-specific investigations using precise and accurate measurement technology to better assess the environmental impact of HVO blends. While numerous studies have examined the effects of HVO on engine emissions and performance, comprehensive experimental investigations of various working points of light duty vehicles are limited.

Emission-based fuel development offers a promising pathway to reduce emissions and promote sustainable alternatives. However, this requires accurate, real-time measurement of the physicochemical properties of particles dispersed in a rapidly changing and reactive gas mixture—an endeavor that presents numerous technical challenges. Furthermore, traditional compliance parameters for CPM—particle number and mass concentration—fail to capture its complex composition and behavior. Therefore, an integrated, real-time infrastructure measuring size distribution and spectral responses is essential to understand the health and climate impacts of exhaust PM.

Exhaust PM properties are specific to engine type, operational mode, and fuel composition30,31. Recent studies have demonstrated that emissions are temperature-sensitive and tend to increase under colder conditions32,33,34. With rapid advancements in emission control technology, updating emission source profiles is vital for accurate source and impact assessment. This highlights the necessity to quantify the optical, chemical, and toxicological characteristics of BC and OM in PM emission. BC content in exhaust PM can vary from 5 to 90%, depending on engine type, operating conditions, and after-treatment technologies35. Moreover, internal mixing of OM with BC enhances light absorption36. As PM evolves, the ratio of volatile to non-volatile components shifts with temperature. The volatility assessments of diesel emissions indicate the fraction of OM that evaporates at a given temperature. High molecular weight vapors may condense onto non-volatile soot particles or nucleate into new particles, altering the chemical composition and mixing state of exhaust PM. In our recent biofuel blended emissions study, we observed that while particle number concentrations decreased at higher engine loads, the BC emissions increased. This finding negates the general assumption that lower particle counts necessarily equate to better emission quality30. While wavelength-dependent spectral responses are informative30,37, comprehensive exhaust PM characterization requires detailed analysis of particle size distribution, morphology, and chemical composition. Such characterization depends on real-time, in situ protocols involving multiple instruments for PM emission characterization. Volatility classification of PM can be achieved using a thermodenuder (TD), which pre-treats aerosols prior to analysis with instruments including a Scanning Mobility Particle Sizer (SMPS) and an Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (AMS) under controlled exhaust temperature conditions38,39,40.

Photoacoustic spectroscopy (PAS) has emerged as the most accurate, in-situ, filter-free technique for measuring aerosol light absorption41. PAS enables direct, fast, and reliable measurements and overcomes limitations inherent in filter-based or differential extinction-scattering methods. Multi-wavelength PAS systems have further advanced the field, enabling comprehensive spectral profiling of CPM and offering new avenues for environmental impact analysis. The absorption Ångström exponent (AAE), derived from the slope of log–log spectral absorption data, is the only real-time measurable parameter offering insight into aerosol composition and source information42,43,44,45,46. In recent years, PAS has matured into a standard for exhaust PM studies, including diesel and biodiesel blend exhaust characterization30,47. By integrating size distribution measurements with spectral responses from thermally treated PM emission, we gain a deeper understanding of aerosol behavior under varying conditions.

This study presents real-time characterization of engine exhaust particles generated by HVO diesel blend using an integrated measurement system. The setup combines PAS with a thermodenuder (TD) that thermally separates volatile organic particles from non-volatile soot, and a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS) to simultaneously monitor spectral responses and particle size distributions. This comprehensive instrumentation suite allows for detailed evaluation of exhaust emissions under varying engine load and fuel injection parameters. We report measurements of particle number concentration, size distribution, and absorption spectra across different operating conditions, interpreting spectral responses regarding size distribution. Additionally, we compare emissions from HVO-blended and conventional diesel fuels. Our results provide new insights into the emission-reduction potential of HVO and enhance understanding of the physicochemical behavior of exhaust PM, addressing fuel optimization and emission control strategies.

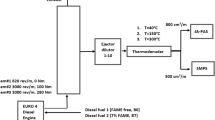

Instrumentation

The experimental setup used for characterizing PM emissions is illustrated in Fig. 1. All measurements were conducted at the engine test laboratory of the Refining Research and Innovation MOL Experiment Centre in Százhalombatta, Hungary. A four-cylinder, 2-L, turbocharged diesel engine (EURO 4 passenger car, common rail injection system) was employed to generate DPM emissions. The engine specifications are provided in Table 1. The engine was operated under three constant-speed modes defined by specific torque and revolutions per minute (rpm) values. These Wps—idle (Wp1), moderate load (Wp2), and high load (Wp3)—were chosen to represent diverse real-world driving conditions (urban idling, highway cruising, and heavy acceleration). The corresponding engine working points (Wps) and exhaust conditions are detailed in Table 2. Two fuel types were tested: B0 (reference fuel) and HVO7 (7% hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) blended with B0). This study focuses on the emission characterization from HVO7-blended fuel. The exhaust emission was diluted isokinetically using a PALAS VKL-10 ejector diluter set to a nominal 1:10 dilution ratio. Dilution air pressure was maintained at 2.0 bar, and sample flow to the diluter was kept constant during steady-state engine operation to ensure stable performance. Dilution ratio stability was evaluated indirectly via the repeatability of the SMPS-measured total particle number concentration, which exhibited less than ± 3% variation across consecutive scans under identical engine conditions. The diluted exhaust was directed through a TD before entering the custom PAS instruments and the scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS).

A Fierz-type TD48 was used in this study, operated at 40 °C and 250 °C. The size distribution measurements were performed using the SMPS system (TSI, SMPS 3938) while real-time aerosol light absorption in the UV to near-infrared wavelength domain was measured using a custom-based Multi-Wavelength Photoacoustic Spectroscopy system (4λ-PAS) developed by us49. The SMPS system consisted of a Long Differential Mobility Analyzer (LDMA, Model 3082) and a Condensation Particle Counter (CPC, Model 3752). Particles were first classified according to their electrical mobility by the LDMA and subsequently counted by the CPC, covering a size range from 11 to 1083 nm, with a size resolution of ± 0.5 nm and a counting resolution of ± 30 particles/cm3. Coincidence and multiple charge corrections were applied throughout the campaign to ensure measurement accuracy. The SMPS was operated with a sheath flow rate (SFR) of 3 L/min and an aerosol flow rate (AFR) of 0.3 L/min, ensuring a stable flow ratio50,51. The 4λ-PAS simultaneously measures optical absorption coefficient (OAC) at 266 nm, 355 nm, 532 nm, and 1064 nm using identical optical cells with an extraction rate of 0.5 L/min. The sensitivity of the instrument is < 1 Mm−1 at 1064 nm, ~ 5 Mm−1 at 532 nm, ~ 23 Mm−1 at 355 nm, and ~ 35 Mm−1 at 266 nm, corresponding to a mass sensitivity of ≤ 1 µg/m3 across all wavelengths49. In addition, a dual-wavelength PAS instrument was used to measure OAC at 1064 nm and 405 nm, providing complementary spectral data. The Wps of the engine were determined based on rpm and torque settings. The engine started at idle (820 rpm, 0 Nm) for 15 min to stabilize coolant temperature. The PALAS VKL 10 diluter was then activated. Immediately thereafter, SMPS, photoacoustic, and thermodenuder measurements were initiated. For each working point, five repeated scans were performed, and the average results are reported. This procedure was repeated consistently across all operating conditions.

Results and discussion

Size distribution measurements

In the present study, an SMPS was employed to determine the mobility size distribution of exhaust PM. Figure 2 shows the size-resolved number concentrations of particles emitted from the engine exhaust. The data were analyzed using a lognormal fitting algorithm. Each data point represents the mean of five measurement cycles, and the associated uncertainties are shown as error bars. Key size distribution parameters, including geometric mean diameter (GMD), geometric standard deviation (GSD), total number concentration (TNC), and total mass concentration (TMC), were derived from the measurements and are summarized in Table 3. The effective densities of 0.8 g cm−3 (≤ 50 nm) and 1.8 g cm−3 (> 50 nm) were applied to convert number distributions to mass concentrations of exhaust PM. These values represent the lower-density organic nucleation mode and the denser soot-dominated accumulation mode, respectively, and are consistent with reported effective densities for diesel exhaust particles52,53. Additionally, the total volume concentration (TVC) was estimated using a simple approximation of spherical particles for all engine Wps and TD temperatures. Figure 3 presents the variations in TNC, GMD, GSD, and TVC across the different engine operating conditions. With increasing engine load and thermodenuder temperature, noticeable variations in particle size distribution parameters are observed for both fuels. These changes arise from higher combustion temperatures and modified air–fuel mixing, which reduce the condensation of volatile organics. Furthermore, as the temperature increases, volatile components progressively evaporate, thereby eliminating the volatile mode and leaving only the refractory soot core.

A detailed comparison of the emission characteristics between the HVO-blended and conventional diesel fuels reveals similarities and notable differences, depending on engine load and thermal conditions. Overall, the HVO7 blend exhibits lower particle concentrations than B0 across all working points and temperatures, with the most substantial reduction observed under idle conditions and at 40 °C TD temperature, as shown in Fig. 2. This reduction is primarily attributed to HVO’s paraffinic composition, which contains no aromatic compounds or sulfur. Aromatic hydrocarbons, particularly benzene rings, are known soot precursors under fuel-rich combustion conditions. The absence of these species suppresses soot nucleation and growth. This reduction gradually diminishes with increasing engine load and TD temperature. These findings are consistent with a recent study54, supporting the emission reduction potential of HVO blends, particularly under low-load operating conditions. Notably, a bimodal particle size distribution was observed under idle conditions (Wp1) at 40 °C for both fuels30,55, whereas unimodal distributions were dominant at other operating points and 250 °C TD temperatures, shown in Fig. 2.

The distinct bimodal pattern at idle conditions highlights the influence of combustion and post-combustion dynamics on particle formation. While an in-depth analysis of bimodal soot emissions requires dedicated measurements beyond the scope of this study, a plausible interpretation grounded in particle dynamics literature is presented here. The smaller mode—characterized by a lower GMD—is likely composed of liquid-phase particles, primarily volatile organic compounds formed through heterogeneous condensation. In contrast, the larger mode corresponds to solid-phase soot particles, consisting of graphitic or turbostratic nano-aggregates that form through nucleation, condensation, and aggregation processes47,56,57. Although minimal cross-over between the two size modes may occur, their distinct contributions remain largely independent. Both fuels exhibit this bimodal distribution under idle and low-temperature conditions, with a dominance of the larger particle mode, as indicated by the higher GMD values, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 3.

The particle concentration and size distribution differences underscore the environmental trade-offs between HVO-blended and fossil-derived fuels. At idle (Wp1) and 40 °C TD temperature, HVO7 emitted over 30% fewer particles than B0. This reduction narrowed to 20% at moderate engine load (Wp2) and to 6% at the highest load (Wp3). However, this decrease in TNC is accompanied by an increase in particle size (GMD) with engine load. For all Wps at 40 °C, the HVO7 fuel produced larger particles than B0, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 3.

The thermal behavior of the emitted particles was also evaluated by increasing the TD temperature to 250 °C. At this temperature, particle concentrations decreased significantly for both fuels compared to 40 °C, likely due to enhanced soot oxidation and the evaporation of volatile species. Under elevated TD temperature, HVO7 maintained its advantage at low and medium loads (Wp1 and Wp2), emitting 20% and 13% fewer particles, respectively, compared to B0. Interestingly, this trend reversed at high load (Wp3)—HVO7 fuel emitted 20% more particles than B0. This unexpected outcome may indicate that HVO7 combustion dynamics could favor new particle nucleation over oxidation under high torque and thermal stress, implying a less homogeneous fuel–air mixture in the cylinder originated from the typical C15–C18 carbon number of HVO. Less volatile fuels require more time for complete evaporation and mixing. If the available time is insufficient for complete vaporization and mixing, pyrolysis reactions over oxidation will dominate the locally fuel-rich regions58. However, quantifying this hypothesis requires either a glass engine measurement or a high-fidelity numerical investigation, which are outside the scope of the current study. At 250 °C, the GMD of HVO7 emitted particles was consistently lower than that for B0 fuel across all working points, reversing the trend observed at 40 °C.

The change in particle size behavior with temperature is evident in Fig. 3 and Table 3. It may be attributed to differences in the thermal decomposition and oxidation characteristics of the two fuels. Key emission parameters—TNC, TVC, GMD, and GSD—varied significantly with engine load, as shown in Fig. 3. TNC decreased from Wp1 to Wp2 for both fuels for the following reason. Compression ignition engines operate lean at all loads, while the equivalence ratio increases with loading. Therefore, idling means a low equivalence ratio, resulting in a low adiabatic flame temperature. Moreover, the mixture is the least homogeneous at this operating point. The high local equivalence ratio variation, the low adiabatic flame temperature, and the fast hydrogen reactions ultimately lead to PM production here. Improving the first two causes reduces TNC value at higher engine load. TNC remained similar at Wp2 and Wp3 since the engine load was sufficiently high to allow a more complete soot burnout. The reduction in TNC from Wp1 to Wp2 was accompanied by an increase in particle size (GMD) and distribution width (GSD), suggesting enhanced particle aggregation or condensation at higher loads, originating from a less homogeneous fuel–air mixture in the cylinder. However, TVC showed minor variation between Wp1 and Wp2. In contrast, although TNC remained stable between Wp2 and Wp3, as shown in Fig. 2, the relative proportion of larger particles increased, resulting in a sharp increase in TVC, shown in Fig. 3 and Table 3. This behavior was observed for both fuels at 40 °C, indicating a shift in particle population dynamics under high-load operation. However, at 250 °C, the trends between operating points differed from those observed at 40 °C. Overall, HVO7 produced fewer particles than the reference fuel, except at Wp3, where increased particle concentration was measured.

Light absorption measurements and lensing effect

Effect of HVO blended fuel and B0 fuel on light absorption measurement

The OAC of emitted particles was measured using our custom-built photoacoustic instruments: the 4λ-PAS and a dual-wavelength photoacoustic (PA) system (2λ-PAS). Figure 4 presents the wavelength-dependent OAC values for both fuels across various engine loads and two TD temperatures. PAS, as employed in our study, provides highly precise in-situ measurements of aerosol absorption with excellent temporal resolution and relatively low uncertainty. Nevertheless, several factors contribute to the overall uncertainty in the reported absorption measurements. The main sources of uncertainty arise from variation in mass concentration in the photoacoustic resonator and instrumental noise and signal drift in the PA systems. In practice, the instrumental noise leads to a baseline signal, which is subtracted from the originally measured PA signal. The measurement uncertainty for each OAC data point was within 5%. The optical absorption characteristics of PM vary significantly with wavelength, offering valuable insights into the composition of carbonaceous aerosols originating from engine exhaust based on spectral responses30,35,37,42. As expected, the absorption of carbonaceous particles increases toward shorter wavelengths in Fig. 4. HVO-blended fuel showed consistently lower OAC values than diesel across all loads and TD temperatures (Fig. 4). OM components—including volatile organic compounds (VOCs), semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—exhibit negligible absorption in the near-infrared region. Consequently, this spectral range serves as a reliable indicator for quantifying BC mass concentrations, which correspond to the inorganic carbon fraction of exhaust PM. In contrast, aerosol absorption in the UV domain is primarily attributed to the OM content. Therefore, this spectral range is particularly useful for identifying the contribution of OM to PM absorption. Across all measured wavelengths, OAC values increase consistently with engine load, regardless of fuel type or TD temperature, as shown in Fig. 4. This trend indicates a clear correlation between engine load and increased BC emissions, as demonstrated by the elevated OAC values at 1064 nm—where absorption is predominantly due to BC, as shown in Fig. 4 and Table 3. The OM content of DPM can be inferred efficiently from OAC measurements at 266 nm. While BC absorption typically follows a 1/λ dependence from NIR to UV35, any significant upward deviation at shorter wavelengths (e.g., 266 nm) suggests additional absorption due to OM. This excess absorption enables quantitative estimation of OM contribution to PM from exhuast. For instance, for B0 fuel at idle engine mode and 40 °C, the extrapolated BC baseline OAC (based on the 1/λ trend) is 512 Mm−1@266 nm, while the measured OAC at 266 nm is 1737 Mm−1 as shown in Fig. 4 and Table 3. This corresponds to an OM-induced absorption enhancement accounting for 71% of the total OAC, yielding an OM/BC ratio of 2.4 at 266 nm. These findings are consistent with previous studies on fresh diesel aerosols, which report UV absorption enhancements from OM in the 50–80% range59. Fuel composition governs these effects. For example, under identical conditions, HVO blends exhibit even higher OM dominance (80% at 266 nm). However, at higher load points (Wp2 and Wp3), OM contributions decline substantially for both fuel types, i.e., B0: 26% and 12%, while HVO: 7% and 3% at Wp2 and Wp3, respectively. These results highlight the temperature- and load-dependent evolution of carbonaceous aerosol composition, with HVO blends demonstrating greater sensitivity to operating conditions than conventional petroleum-based diesel fuel.

A plausible explanation for the increasing OAC towards shorter wavelengths (VIS-UV) range involves shifts in the size distribution of emitted particulate matter as well as increased absorption ability of OM content35,46.

The notable insights can be drawn when the OAC data are examined in conjunction with the particle size distribution. At any given temperature and for both fuels, the BC content of diesel particulate matter, as indicated by the measured OAC at 1064 nm, increased with rising engine load (Fig. 4, Table 4). In contrast, at T = 40 °C, the particle number concentration decreased sharply from low-load (Wp1) to medium-load (Wp2) conditions and subsequently remained nearly constant between Wp2 and Wp3, as illustrated in Fig. 3 and Table 3. Moreover, at 40 °C, OAC values for HVO-blended fuel are lower than those for B0 at all wavelengths, but HVO exhibits a steeper rise in absorption from visible to UV wavelengths, as shown in Fig. 4, indicating a different particle composition compared to B0 fuel and having higher OM content. In general, one can conclude that HVO blended fuel generates a smaller amount of BC content at all engine loads at T = 40 °C TD temperature.

As the TD temperature rises to 250 °C, the OAC of B0 and HVO blended B0 fuel decreases across all wavelengths, with this trend being less pronounced at 1064 nm and more dominant at UV wavelengths, shown in Fig. 4 and Table 4. This phenomenon can be attributed to the wavelength-dependent absorption properties of OM constituents within the emitted particulate matter. At shorter UV wavelengths, light absorption by semi-volatile organic compounds (e.g., PAHs and oxygenated organics) becomes significant. As TD temperature increases, these organic species undergo thermal desorption (volatilization) from the particle phase, reducing their contribution to the overall OAC. Additionally, volatile OM is partially or completely evaporated at higher temperatures. The weaker temperature dependence of OAC at 1064 nm aligns with the dominance of BC absorption in the infrared range, which remains relatively unaffected by thermal desorption because of its non-volatile nature. For HVO blends, which inherently contain fewer aromatic and oxygenated organics due to their paraffinic composition, the reduction in OAC at higher TD temperatures is dominant at lower engine mode (Wp1) and less pronounced at medium (Wp2) and higher engine load (Wp3), likely due to residual organic content.

The contribution of OM to the total OAC was further investigated by comparing measurements at 40 °C and 250 °C. At elevated temperatures (250 °C), the 1/λ extrapolation method reveals a reduced OM contribution to OAC due to thermal desorption of semi-volatile organic compounds. Specifically, at idle engine conditions (Wp1), OM accounts for 34% of OAC in B0 diesel and 28% in HVO7 fuel at 250 °C—significantly lower than measured at 40 °C (71% for B0, 80% for HVO7). This decrease is attributed to the volatilization of light-absorbing OM species (e.g., oxygenated aromatics, PAHs) at high TD temperature. Under higher engine loads (Wp2 and Wp3), the trends diverge: B0 diesel exhibits a predictable decline in OM contribution (26% → 5%), consistent with enhanced combustion efficiency and reduced OM emissions at elevated loads. The HVO blended fuel, however, displays anomalous behavior, with OM contributions increasing to 42% (Wp2) and 50% (Wp3). This irregularity may come from thermally resistant OM fractions (e.g., long-chain oxygenated organics) persisting in HVO combustion aerosols and the paraffinic structure of HVO that could promote the formation of non-volatile, UV-absorbing OM at higher loads, unlike conventional diesel, due to the difference in their typical carbon chain length.

Since the OAC (Mm−1) is an extensive property, its value is directly influenced by aerosol mass concentration, which varies with engine load, as shown in Fig. 2 and summarized in Table 3. This dependence complicates direct comparisons of OAC across different operational conditions. To enable a more meaningful analysis of particle absorption characteristics, it is preferable to use an intensive property, namely the mass absorption cross-section (MAC, in m2/g), defined as MAC = OAC/Mass Concentration11. This normalization removes the influence of varying particle concentrations, allowing a more precise comparison of the intrinsic absorption efficiency of particles across different engine loads. The MAC values were derived from the measured OAC data using a spherical particle model and a diesel soot density of 1.8 g/cm3 52. The resulting MAC values, calculated from photoacoustic measurements, are presented in Fig. 5 and summarized in Table 4. While the general spectral trends of MAC follow those of OAC, the engine load has a pronounced effect on MAC values. Specifically, the idle operating condition (Wp1) consistently results in the lowest absorption efficiency for both fuel types and under all thermal treatment conditions. For conventional petroleum diesel (B0), maximum MAC values are observed under medium load (Wp2) at both TD temperatures. The subsequent decrease at high load (Wp3) may be attributed to several factors, including changes in the oxidation state of BC and shifts in the BC-to-OM ratio. In contrast, the HVO7 fuel exhibits a monotonically increasing trend in MAC values with rising engine load, from idle (Wp1) to high load (Wp3), as shown in Fig. 5 and Table 4. This consistent increase suggests that combustion of HVO7 becomes progressively more efficient, likely due to its higher cetane number and lower aromatic content20, which ultimately produces strongly light-absorbing particles as the engine load increases.

Lensing effect and AAE investigation using HVO blended and B0 fuels

Light absorption enhancement \({E}_{\text{abs}}\) quantifies the amplification of light absorption by a particle due to the presence of coatings or morphological modifications60, defined as the ratio of the absorption coefficient of a coated particle to that of its uncoated core37,60,61,62\(:\)

The Eabs(λ, 250 °C) value was influenced by the coating thickness and light-absorbing properties of OM volatilized below 250 °C. At 1064 nm wavelength, the absorption of OM is negligible, and the shape of the BC core does not change with temperature, with heating up to 250 °C. The Eabs(λ, 250 °C) values will represent light enhancement due to coating formation. The lensing effect for the 1064 nm, 250 °C pair is minimal. The Eabs(λ, 250 °C) values are increasing towards lower wavelengths for both B0 and HVO blended fuels in the lower engine mode (Wp1), as presented in Table 5.

The lensing effect at near-IR wavelength Eabs(1064 nm, 250 °C) remains negligible even with increasing engine load for both types of fuels. Generally, the highest lensing effects are observed at Eabs(266 nm, 250 °C). Mixed behavior is also observed between the limits, where BC may exist externally mixed with other components or reside at particle edges, even in particles classified as internally mixed, as shown in Table 5. These observations imply that increasing TD temperature alters particle morphology and mixing states, potentially redistributing BC within the particle matrix or modifying coating homogeneity, thereby complicating Eabs interpretation. To quantify the fractional contribution of organic content (\({OAC}_{\text{OM}}\left(\lambda \right)\)) to the total observed absorption coefficient, OAC(λ), the following relation can be calculated using a procedure similar to that described in62.),

Here, the subtraction of Eabs(1064 nm, 250 °C) effectively removes the BC-driven baseline absorption, isolating the OM contribution. This approach assumes minimal wavelength-dependent lensing artifacts at 1064 nm. The contribution of OM optical absorption and the corresponding optical absorption of exhaust particles at defined wavelengths of the PAS instrument, and different engine loads, is shown in Fig. 6 and summarized in Table 5. The ratio of the absorption of OM to the absorption of exhaust particulate matter (\({OAC}_{\text{OM}}\left(\lambda \right)/OAC\left(\lambda \right)\)) increases towards shorter wavelengths for both fuels at idle engine condition (Wp1). At idle (Wp1), the OM-to-total absorption ratio increases at shorter wavelengths, with HVO7 showing a higher ratio (73% at 266 nm) than B0 (55%), likely due to larger particle sizes (GMD) in HVO7 (see Fig. 2, Table 3). At higher engine loads (Wp2, Wp3), OM contributions drop significantly (7–8% for HVO7, 10–22% for B0), reflecting improved combustion efficiency. These trends, summarized in Fig. 6 and Table 5, highlight the sensitivity of OM to engine conditions. A mixed trend observed from higher to lower wavelengths, most likely due to varying particle population statistics at higher engine loads (Wp2 and Wp3) for both fuels, as presented in Table 5. At longer wavelengths, BC dominates absorption, reducing the role of OM. Uncertainties arise from potential heating-induced changes in particle morphology, such as core–shell collapse, which may affect lensing or BC aggregation. Despite these, the method robustly quantifies the optical impact of OM, offering insights into fuel and engine effects on aerosol absorption.

The measured OAC using PAS as a function of different engine loads and T = 250 °C (squares), and OAC of OM (\({\text{OAC}}_{\text{OM}}\left(\uplambda \right)\)) values evaluated using Eq. (2) (circles). The vertical lines at 266 nm show the point where we quantify the OM content in exhaust PM.

Besides the lensing effect, the AAE is also a powerful alternative for investigating the OM effect on the measured absorption11,46,62. The calculated AAE values, deduced from measured OACs across varying operational wavelengths of photoacoustic instruments, are illustrated in Fig. 7 and detailed in Table 6. Notably, OAC is an extensive property (dependent on analyte mass concentration), whereas AAE is an intensive property (independent of concentration). The AAE reflects the combined absorption characteristics of organic and inorganic components and the mixing state of the sample. Moreover, the AAE is the only real-time measurable physical quantity that can be correlated to the offline measurable organic carbon to elemental carbon ratio (OC/EC), which is also a crucial parameter for CPM characterization63. Based on that, an AAE value around 1 means the dominance of the elemental or BC fraction having a lower OC/EC ratio, while higher values of AAE indicate the presence of organic fraction in the particle assembly (higher OC/EC ratio)46,64. At 40 °C TD temperature, the highest AAE occurs at idle engine speed (Wp1), indicating strong contributions from OC (equivalent to OM in PM emission) with high absorption capability. As engine load increases, AAE values decline progressively, reflecting a shift toward EC (BC content in PM emissions). For example, B0 fuel exhibits its lowest AAE (1.1) at high-load and posterior temperature conditions (Wp3, 250 °C), where minimal OM in exhaust emissions presence aligns with improved combustion efficiency, as shown in Fig. 7. The HVO blended fuel mirrors this general trend but shows elevated AAE at idle (Wp1) and 40 °C TD temperature, highlighting the enhanced absorption role of OM under low-temperature, low-load conditions. At 250 °C TD temperature, AAE trends of HVO correlate with B0 across all engine modes (Wp1–3). The TD temperature plays a critical role: elevating to 250 °C uniformly reduces AAE values for all fuels and conditions, with the most pronounced deviations at idle (Wp1), likely due to OM volatilization diminishing spectral absorption. The HVO blended fuel shows greater AAE deviations between 40 °C and 250 °C than B0 across all modes, reflecting its heightened temperature sensitivity. These trends correlate with the lensing effect, as shown in Fig. 6, where OM content evaporation dynamics influence absorption. The maximum deviation of OM absorption from total particulate matter absorption is observed at Wp3, i.e., the highest OM evaporates below 250 °C for both fuels at Wp3, and the lowest OM evaporates at Wp1. The minimum evaporation of OM below 250 °C is observed for HVO blended fuel at Wp1, i.e., 7% corresponds to the highest value of AAE of HVO7 fuel at Wp1.

This study also explores the interplay between aerosol size distributions and optical properties by examining trends in OACs and AAEs in relation to TNC, TVC, and other parameters across engine operating modes and thermodenuder temperatures. Comparative analysis of size and optical data reveals that TNC decreases from low-load idle (Wp1) to medium load (Wp2) before stabilizing at high load (Wp3), a pattern consistent across fuels and TD temperatures (40 °C). In contrast, OAC rises progressively with engine load, with stronger increases at shorter (UV) wavelengths, signaling heightened contributions from both OM and BC as mass-loading grows. Since photoacoustic signals scale with particle mass, TVC serves as an effective proxy for OAC behavior: it holds steady from Wp1 to Wp2 (mirroring limited mass changes amid TNC reductions) but surges sharply from Wp2 to Wp3, directly paralleling the load-driven OAC escalation. Meanwhile, AAE declines steadily from Wp1 to Wp3, reflecting a shift toward BC-dominated absorption (lower AAE) over OM influence as combustion efficiency improves; this BC enrichment is accentuated at high loads and 250 °C TD, where enhanced soot oxidation further suppresses OM. For HVO7 blends, TVC consistently undercuts B0 values across all conditions, yielding correspondingly lower OAC signals. Yet, HVO7 exhibits elevated AAE at 40 °C under idle (Wp1), pointing to amplified relative OM absorption amid reduced overall soot, likely from cooler cylinder temperatures hindering burnout. Overall, OAC and AAE trends—rising OAC with TVC at higher loads, falling AAE with declining TNC/OM fractions—effectively delineate fuel- and load-specific dynamics, positioning AAE as a powerful indicator for disentangling combustion efficiency from compositional shifts in exhaust aerosols, as corroborated by integrated TNC/TVC profiles.

Conclusions

We demonstrated a comprehensive real-time characterization of PM emissions from hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO7)–blended diesel compared to conventional diesel (B0) using an integrated measurement system combining photoacoustic spectroscopy (PAS), scanning mobility particle sizing (SMPS), and a thermodenuder (TD). This approach provides simultaneous insight into both the physical and chemical properties of exhaust aerosols across engine loads and temperatures. The custom multi-wavelength PAS, including UV wavelengths, enables direct quantification of the organic matter (OM) fraction in PM emissions, overcoming limitations of traditional filter-based or visible-only absorption methods. Parallel measurements of volatility-based size distributions and spectral responses allow detailed characterization of exhaust PM in the context of health and climate impacts. Combining PAS with SMPS facilitates a comprehensive quantitative and qualitative analysis of BC and OM content across varying engine loads and TD temperatures.

The results show that HVO7 reduces particle number concentrations by up to 30% at idle (40 °C), although this reduction diminishes at higher loads and TD temperatures. HVO7 produces larger particles at 40 °C but smaller particles at 250 °C compared to B0, indicating temperature-dependent particle dynamics. While total particle number decreases with increasing load, the BC fraction increases, reflecting enhanced soot formation under higher combustion temperatures. At 40 °C, HVO7 emits less BC and exhibits higher OM content at idle (80% vs. 71% for B0). At higher loads, OM contributions decrease sharply (HVO7: 7% and 3%; B0: 26% and 12% for medium and high loads, respectively), demonstrating the fuel’s sensitivity to operating conditions. At 250 °C, HVO7 shows lower OM content (28%) than B0 (34%), consistent with thermal volatilization effects. The Absorption Ångström Exponent (AAE) decreases with increasing load for both fuels, with HVO7 displaying higher values at 40 °C, reflecting greater OM contributions. These trends align with observed lensing effects in DPM emissions.

The observed emission trends are closely linked to engine performance characteristics. Increasing torque and speed at higher working points corresponds to enhanced combustion efficiency and elevated in-cylinder temperatures, promoting more complete oxidation of soot precursors. Consequently, TNC decreases, while GMD increases due to enhanced agglomeration of soot particles. Higher exhaust gas temperatures further reflect improved thermal efficiency under load.

Overall, the proposed integrated multi-instrument approach enables simultaneous quantitative and qualitative assessment of PM, linking particle number, size, composition, and optical properties with engine operating conditions. The proposed integrated measurement approach enhances understanding of the physicochemical behavior of PM emission, providing valuable insights for fuel optimization and emission control strategies to improve air quality and environmental sustainability.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhang, J.J., McCreanor, J.E., Cullinan, P., Chung, K.F., Ohman-Strickland, P., Han, I.K., Järup, L. & Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Health effects of real-world exposure to diesel exhaust in persons with asthma. Res. Rep. Health Eff. Inst. 138, 5–109; discussion 111–123 (2009).

Zhao, H. et al. Non-allergic eosinophilic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness induced by diesel engine exhaust through activating ILCs. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 278, 116403 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Effects of diesel exposure on lung function and inflammation biomarkers from airway and peripheral blood of healthy volunteers in a chamber study. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 10, 60 (2013).

Nordenhäll, C. et al. Acute exposure to diesel exhaust increases IL-8 and GRO-α production in healthy human airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161, 550–556 (2000).

Törnqvist, H. et al. Persistent endothelial dysfunction in humans after diesel exhaust inhalation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176, 395–400 (2007).

Wauters, A. et al. Acute exposure to diesel exhaust impairs nitric oxygen–mediated endothelial vasomotor function by increasing endothelial oxidative stress. Hypertension 62, 352–358 (2013).

Mills, N. L. et al. Combustion-derived nanoparticulate induces the adverse vascular effects of diesel exhaust inhalation. Eur. Heart J. 32, 2660–2671 (2011).

Qian, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, X. & Lu, X. Particulate matter emission characteristics of a reactivity controlled compression ignition engine fueled with biogas/diesel dual fuel. J. Aerosol Sci. 113, 166–177 (2017).

Kittelson, D. B. Engines and nanoparticles: A review. J. Aerosol Sci. 29, 575 (1998).

Andreae, M. O. & Ramanathan, V. Climate’s dark forcings. Science 340(6130), 280–281 (2013).

Bond, T. C. et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: A scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 5380 (2013).

Vörösmarty, M., Hopke, P. K. & Salma, I. Attribution of aerosol particle number size distributions to major sources using an 11-year-long urban dataset. EGUsphere 2024, 1–28 (2024).

Chen, Y.-H., Bo-Yu, H., Tsung-Han, C. & Tang, T.-C. Fuel properties of microalgae (Chlorella protothecoides) oil biodiesel and its blends with petroleum diesel. Fuel 94, 270–273 (2012).

Singer, A. et al. Aging studies of biodiesel and HVO and their testing as neat fuel and blends for exhaust emissions in heavy-duty engines and passenger cars. Fuel 153, 595–603 (2015).

Ohshio, N., Saito, K., Kobayashi, S. & Tanaka, S. Storage stability of FAME blended diesel fuels. SAE Tech. Pap. 2008-01-2505 (2008).

Hartikka, T., Kuronen, M. & Kiiski, U. Technical performance of HVO (Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil) in diesel engines. SAE Tech. Pap. 2012-01-1585 (2012).

Aatola, H., Larmi, M., Sarjovaara, T. & Mikkonen, S. Hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) as a renewable diesel fuel: trade-off between NOx, particulate emission, and fuel consumption of a heavy duty engine. SAE Int. J. Engines 1(1), 1251–1262 (2009).

Kuronen, M., Mikkonen, S., Aakko, P. & Murtonen, T. Hydrotreated vegetable oil as fuel for heavy duty diesel engines. SAE Tech. Pap. 2007-01-4031 (2007).

Rodríguez-Fernández, J., Lapuerta, M. & Sánchez-Valdepeñas, J. Regeneration of diesel particulate filters with hydrotreated vegetable oil. Fuel 197, 557 (2017).

Dimitriadis, A. et al. Evaluation of a hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) and effects on emissions of a passenger car diesel engine. Front. Mech. Eng. 4, 7 (2018).

McCaffery, C. et al. Effects of hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) and HVO/biodiesel blends on the physicochemical and toxicological properties of emissions from an off-road heavy-duty diesel engine. Fuel 323, 124283 (2022).

Sugiyama, K., Goto, I., Kitano, K., Mogi, K. & Honkanen, M. Effects of hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) as renewable diesel fuel on combustion and exhaust emissions in a diesel engine. SAE Tech. Pap. 2011-01-1954 (2012).

Karavalakis, G. et al. Emissions and fuel economy evaluation from two current technology heavy-duty trucks operated on HVO and FAME blends. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 9(1), 177–190 (2016).

Prokopowicz, A., Zaciera, M., Sobczak, A., Bielaczyc, P. & Woodburn, J. The effects of neat biodiesel and biodiesel and HVO blends in diesel fuel on exhaust emissions from a light-duty vehicle with a diesel engine. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 7473–7482 (2015).

No, S. Y. Application of hydrotreated vegetable oil from triglyceride-based biomass to CI engines—a review. Fuel 115, 88–96 (2014).

Westphal, G. A. et al. Combustion of hydrotreated vegetable oil and jatropha methyl-ester in a heavy-duty engine: emissions and bacterial mutagenicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47(11), 6038–6046 (2013).

Athanasios, D. Athanasios, D. Stylianos, D. Berzegianni, S. & Samaras, Z. Emissions optimization potential of a diesel engine running on HVO: a combined experimental and simulation investigation. SAE Tech. Paper, 2019-24-0039 (2019).

Suarez-Bertoa, R. et al. Impact of HVO blends on modern diesel passenger cars emissions during real world operation. Fuel 235, 1427–1435 (2019).

Stumborg, M., Wong, A. & Hogan, E. Hydroprocessed vegetable oils for diesel fuel improvement. Bioresour. Technol. 56, 13–18 (1996).

Ajtai, T. et al. The investigation of diesel soot emission using instrument combination of multi-wavelength photoacoustic spectroscopy and scanning mobility particle sizer. Sci. Rep. 14, 2254 (2024).

Gangwar, J. N., Gupta, T. & Agarwal, A. K. Composition and comparative toxicity of particulate matter emitted from a diesel and biodiesel fuelled CRDI engine. Atmos. Environ. 46, 472–481 (2012).

Wen, Y., Zhang, S., He, L. & Wu, Y. Characterizing start emissions of gasoline vehicles and the seasonal, diurnal and spatial variabilities in China. Atmos. Environ. 245, 118040 (2021).

Yusuf, A. A. & Inambao, F. L. Effect of cold start emissions from gasoline-fueled engines of light-duty vehicles at low and high ambient temperatures: Recent trends. Case Stud Thermal Eng 14, 100417 (2019).

Zhu, R. et al. Effects of ambient temperature on regulated gaseous and particulate emissions from gasoline-, E10- and M15-fueled vehicles. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 15, 14 (2021).

Moosmüller, H. et al. Time-resolved characterization of diesel particulate emissions. 2. Instruments for elemental and organic carbon measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35, 1935–1942 (2001).

Schnaiter, M. et al. UV-VIS-NIR spectral optical properties of soot and soot-containing aerosols. J. Aerosol Sci. 34, 1421–1444 (2003).

Guo, X. et al. Measurement of the light absorbing properties of diesel exhaust particles using a three-wavelength photoacoustic spectrometer. Atmos. Environ. 94, 428–437 (2014).

Gren, L. et al. Effects of renewable fuel and exhaust aftertreatment on primary and secondary emissions from a modern heavy-duty diesel engine. J. Aerosol Sci. 156, 105781 (2021).

Korhonen, K. et al. Particle emissions from a modern heavy-duty diesel engine as ice nuclei in immersion freezing mode: A laboratory study on fossil and renewable fuels. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22(3), 1615–1631 (2022).

Ranjan, M., Presto, A. A., May, A. A. & Robinson, A. L. Temperature dependence of gas–particle partitioning of primary organic aerosol emissions from a small diesel engine. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 46(1), 13–21 (2011).

Beck, H. A., Niessner, R. & Haisch, C. Development and characterization of a mobile photoacoustic sensor for on-line soot emission monitoring in diesel exhaust gas. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 375(8), 1136–1143 (2003).

Utry, N. et al. Correlations between absorption Angström exponent (AAE) of wintertime ambient urban aerosol and its physical and chemical properties. Atmos. Environ. 91, 52–59 (2014).

Pintér, M. et al. Investigation of the optical and physical properties of urban aerosol particles during nucleation events. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 17, 665–676 (2017).

Pintér, M. et al. Optical properties, chemical composition and the toxicological potential of urban particulate matter. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 17, 1515–1526 (2017).

Filep, Á. et al. Absorption spectrum of ambient aerosol and its correlation with size distribution in specific atmospheric conditions after a red mud accident. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 13, 704–715 (2013).

Ajtai, T. et al. A method for segregating the optical absorption properties and the mass concentration of winter time urban aerosol. Atmos. Environ. 122, 313–320 (2015).

Ajtai, T. et al. Diurnal variation of aethalometer correction factors and optical absorption assessment of nucleation events using multi-wavelength photoacoustic spectroscopy. J. Environ. Sci. 83, 96–109 (2019).

Fierz, M., Vernooij, M. G. C. & Burtscher, H. An improved low-flow thermodenuder. J. Aerosol Sci. 38, 1163–1168 (2007).

Ajtai, T. et al. A novel multi-wavelength photoacoustic spectrometer for the measurement of the UV–vis–NIR spectral absorption of atmospheric aerosols. J. Aerosol Sci. 41, 1020–1029 (2010).

Ristimäki, J., Virtanen, A., Keskinen, J. & Maricq, M. M. On-line measurement of diesel exhaust particle size distribution with a DMPS. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 36(7), 749–757 (2002).

Belosi, F., Prodi, F., Contini, D., Donateo, A. & Santachiara, G. Comparison between two different nanoparticle size spectrometers for ambient and source measurements. Aerosol Air Quality Res 13(1), 180–190 (2013).

Park, K., Cao, F., Kittelson, D. B. & McMurry, P. H. Relationship between particle mass and mobility for diesel exhaust particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 37(3), 577–583 (2003).

Maricq, M. M. & Xu, N. The effective density and fractal dimension of soot particles from premixed flames and motor vehicle exhaust. J. Aerosol Sci. 35(10), 1251–1274 (2004).

Bortel, I., Vávra, J. & Takáts, M. Effect of HVO fuel mixtures on emissions and performance of a passenger car size diesel engine. Renew. Energy 140, 680–691 (2019).

Ushakov, S., Valland, H., Nielsen, J. B. & Hennie, E. Particle size distributions from heavy-duty diesel engine operated on low-sulfur marine fuel. Fuel Process. Technol. 106, 350–358 (2013).

Ajtai, T., Kohut, A., Raffai, P., Szabó, G. & Bozóki, Z. Controlled laboratory generation of atmospheric black carbon using laser excitation-based soot generator: From basic principles to application perspectives: A review. Atmosphere 13(9), 1366 (2022).

Andreae, M. O. & Gelencsér, A. Black carbon or brown carbon? The nature of light-absorbing carbonaceous aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 3131 (2006).

Tan, C. et al. Investigation on transient emissions of a turbocharged diesel engine fuelled by HVO blends. SAE Int. J. Engines 6(2), 1046–1058 (2013).

Kirchstetter, T. W., Aguiar, J., Tonse, S., Fairley, D. & Novakov, T. Black carbon concentrations and diesel vehicle emission factors derived from coefficient of haze measurements in California: 1967–2003. Atmos. Environ. 42, 480 (2008).

Kong, Y. et al. A review of quantification methods for light absorption enhancement of black carbon aerosol. Atmos. Environ. 301, 119720 (2023).

Fierce, L. et al. Radiative absorption enhancements by black carbon controlled by particle-to-particle heterogeneity in composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117(10), 5196–5203 (2020).

Cappa, C. D. et al. Radiative absorption enhancements due to the mixing state of atmospheric black carbon. Science 337, 1078–1081 (2012).

Favez, O., Cachier, H., Sciare, J., Sarda-Estève, R. & Martinon, L. Evidence for a significant contribution of wood burning aerosols to PM2.5 during the winter season in Paris, France. Atmos. Environ. 43, 3640–3644 (2009).

Smausz, T. et al. Determination of UV–visible–NIR absorption coefficient of graphite bulk using direct and indirect methods. Appl. Phys. A 123, 1–7 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH) of Hungary through project 2022−2.1.1-NL-2022-00012. This work was also supported by the “Production and validation of synthetic fuels in industry-university collaboration” (ÉZFF/956/2022-ITM_SZERZ) project.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH) of Hungary through project 2022-2.1.1-NL-2022-00012. This work was also supported by the “Production and validation of synthetic fuels in industry-university collaboration” (ÉZFF/956/2022-ITM_SZERZ) project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H carried out experiments. C.T.C and V.J prepared the Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. M.Q.M and J.X provided technical support and critical review. G.S and Z.B wrote the scientific explaination of Sect. 2. A.R and T.A wrote the main manuscript and interpret the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hodovány, S., Chong, C.T., Józsa, V. et al. Demonstration of particulate matter characterization from HVO-blended diesel using an integrated multi-instrument approach. Sci Rep 16, 2024 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31742-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31742-3