Abstract

This study develops and optimizes a hybrid cooling system that synergizes building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) with earth-air (EAHE) and water-air (WAHE) heat exchangers for solar-powered gym cooling. Two configurations are evaluated: a series arrangement (Configuration A) and a parallel one (Configuration B). A multi-objective optimization using a genetic algorithm was performed to maximize total energy output while minimizing power consumption by optimizing seven design parameters. The results demonstrate a clear performance trade-off: Configuration A achieved superior cooling with a lower outlet air temperature of 14.0 °C, while Configuration B delivered a significantly higher total energy output of 41 kWh in August, a 64% increase over Configuration A’s 25 kWh. The optimization yielded a definitive optimal design point with the following key parameters: an air mass flow rate of 1.18 kg/s, a water mass flow rate of 0.68 kg/s, an EAHE diameter of 0.49 m and length of 23.79 m, and a WAHE diameter of 0.027 m and length of 23 m. Crucially, the BIPV system generated sufficient electricity to power all auxiliary components. This work confirms the viability of a fully renewable, dual-source cooling architecture, with Configuration B recommended for maximizing energy output and Configuration A for prioritizing maximum cooling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unquestionably, one of the biggest issues facing humanity today is energy security. It includes managing a variety of geopolitical, economic, technological, environmental, and psychological risks that impact energy markets while guaranteeing a steady and dependable supply of energy sources at fair rates. A varied geographic distribution of resources, safe transportation routes, and easy access to global oil and gas reserves are all components of energy security for consumers. Furthermore, the oil and gas supply must come from areas that are expected to stay steady and reliable over time. Rapid depletion of underground energy sources necessitates the current generation to prioritize sustainable and long-lasting energy alternatives. The evolving landscape of renewable energy offers a broad spectrum of choices including solar, geothermal, wind, bio, wave, and seawater energy. Although these energy sources have been utilized since ancient times, advancements in science and technology have empowered humanity to harness their potential. However, the escalating industrialization in many developing nations and the global population surge have heightened the demand for various forms of energy, particularly electrical energy. Despite the continuous improvement in energy efficiency of renewables through innovative technologies, fossil fuels persist as predominant energy sources for industrial operations. Consequently, the current contribution of new energy sources to global energy supply remains relatively minimal the predominant reliance on fossil fuels has hindered the widespread adoption of renewable energy sources, despite their numerous benefits. However, the finite nature of fossil fuels and their detrimental environmental impact are becoming increasingly evident. To address these challenges, a shift towards optimizing fossil fuel usage and transitioning to new or renewable energies is essential for environmental improvement and mitigating the energy crisis1,2,3,4.

Among the many renewable energy options, solar panels are among the most widely used. It is anticipated that worldwide solar PV capacity would exceed 500 GW by the end of 2018, which would allow it to supply around 2.8% of the world’s power needs1. These solar panels directly generate energy from sunlight, however they have drawbacks including low electrical conversion efficiency, which is made worse by rising temperatures. To combat these efficiency issues, researchers have proposed utilizing a cooling fluid to enhance the panels’ performance. When panels’ temperatures are reduced to enhance efficiency, they also generate a heated fluid useful for various applications like HVAC systems. Known as photovoltaic/thermal systems, these integrated solutions have been extensively scrutinized for their energetic and exergetic performances by numerous researchers2,3,4,5.

These systems have a wide range of uses, although they are mostly used to enable heating and cooling solutions. Khaki et al.6,7 suggested a PVT system that could produce power and prepare outdoor air in the winter and summer. In addition to multi-criteria optimization for glazed and unglazed PVT systems, their work included in-depth energy and exergy studies. The results indicated that while the glazed system outperformed the unglazed system in first-law performance evaluations, the opposite was true for second-law performance evaluations. Moaleman et al.8 evaluated the performance of a trigeneration system that included a water-ammonia absorption chiller and a concentrating PVT system in a different research. The TRNSYS software was used to run the simulations and assess how well different hybrid energy systems performed. According to Buonomano et al.9, the hybrid system’s average yearly electrical efficiency is around 58%. They evaluated a novel polygeneration system with PVT-driven adsorption and absorption chillers using a dynamic simulation model. According to their findings, using an electric chiller as a backup device in every situation produced the best energy and financial results. A new CCHP system that combines a liquid desiccant system with a PVT system was proposed by Su et al.10. According to their analysis, on an annual basis, energy savings and CO2 emission reductions came to around 73.28% and 74.55%, respectively. As a renewable energy source, geothermal energy has attracted a lot of attention from researchers11. In contrast to solar and wind energy, geothermal energy is consistently available and accessible worldwide. In the winter season, ground temperature is higher than the average outside air temperature, but in the summer season, the converse is true, according to research12,13,14,15. An Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) may use this phenomena to precool or preheat outdoor air. Direct use of geothermal energy involves passing warm or cold air through the earth in the winter or summer to heat or cool the air, while indirect usage involves passing the heat via a second heat transfer fluid in a heat exchanger.

The performance of EAHEs has been the subject of recent investigation by a number of academics16,17,18. The hybrid PVT-EAHE system is a prominent example of the hybrid renewable energy systems that a subset of scientists have investigated. Research on energy and exergy is scarce, according to the literature currently under publication. Only three research have examined the performance evaluation of hybrid PVT-EAHE systems19,20,21. The effectiveness of an integrated PVT-EAHE system in a greenhouse under various climatic conditions in India was examined by Nayak and Tiwari19, who found that Jodhpur was the best site because of its high sun intensity. The energy and exergetic efficiency of a PVT-EAHE system in a solar greenhouse were theoretically examined in a different work by Mahdavi et al.20. Through the EAHE system, greenhouse air was preheated and precooled before being circulated back into the greenhouse. Additionally, the air in the greenhouse was warmed by traveling via a conduit underneath the photovoltaic displays. The hybrid PVT-EAHE system showed the ability to precool and preheat the greenhouse air by 9 °C and 8 °C in the summer and winter, respectively, while the PVT system by itself had no effect on greenhouse air preheating.A numerical evaluation of a PVT-EAHE system’s thermal performance under various climatic conditions in Pilani, Ajmer, India, and Las Vegas, USA, was carried out by Jakhar et al.21. The system efficiently produced power and warmed the chilly ambient air by utilizing the PVT and EAHE technologies. The EAHE’s heating capacity increased from 0.024 to 0.299 kWh for Pilani, from 0.071 to 0.316 kWh for Ajmer, and from 0.041 to 0.271 kWh for Las Vegas as a result of the PVT system’s integration.

Ground-source heat pump (GSHP) systems are among the most energy-efficient solutions for space conditioning, leveraging the near-constant subsurface temperature to achieve high coefficients of performance (COP), typically ranging between 3.0 and 5.0 for well-designed systems22. The thermal stability of the ground at depths beyond 4–6 m, where temperatures remain relatively stable (≈10–16 °C in temperate climates), allows GSHPs to significantly reduce electricity consumption compared to conventional air-source heat pumps22.

Earth-air heat exchangers (EAHEs) further enhance energy efficiency by utilizing the ground’s thermal inertia to precondition ventilation air before it enters HVAC systems. Studies indicate that properly designed EAHEs can reduce cooling loads by 15–30% in summer and heating loads by 10–25% in winter, depending on climatic conditions and soil thermal properties23. The thermo-hydraulic performance of EAHEs is governed by key parameters such as pipe length, diameter, air velocity, and burial depth. For instance, De Paepe and Janssens24 demonstrated that an optimal air velocity of 2–4 m/s minimizes pressure drop while maximizing heat transfer, with typical pressure losses ranging from 50–200 Pa/m depending on pipe roughness and geometry.

The fundamental heat transfer mechanisms in EAHEs conduction through the soil, convection at the pipe-air interface, and thermal storage effects are well-described by Kouki et al.25. The EAHE systems’ performance is not significantly influenced by the pipe material, unlike the pipe length and diameter. It is reported that longer pipes enhance the cooling output in the EAHE system. The pipe length positively correlates with the in-pipe air temperature. An increment in the pipe diameter led to a drop in the in-pipe air temperature. An indicative report states that an increasing air flow velocity can lead to thermal losses from pipes to their surrounding soil25.

Recent advancements integrate EAHEs with hybrid HVAC systems to further improve efficiency. For example, Hernández et al.26 demonstrated that combining an air-to-water heat pump (COP ≈ 3.5) with a ducted fan coil unit and EAHE reduced annual energy consumption by 22% in a residential building. Similarly, Bansal et al.27 reported that earth-pipe-air heat exchangers (EPAHEs) achieved a cooling capacity of 1.5–2.5 kW with a temperature drop of 5–8 °C in summer, reducing peak cooling demand by 20–35%.

Optimization studies have explored hybrid systems combining EAHEs with renewable energy technologies. Khanmohammadi and Shahsavar28 showed that integrating a thermal wheel with a building-integrated photovoltaic/thermal (BIPV/T) system improved overall exergy efficiency by 18–25%. Li et al.29 further optimized a hybrid EAHE-BIPV/T system using multi-objective genetic algorithms, achieving a 30% reduction in energy demand while maintaining thermal comfort, with a payback period of 6–8 years under moderate climate conditions.

These findings underscore the potential of EAHEs and hybrid geothermal systems in decarbonizing building HVAC systems while meeting stringent energy efficiency targets.

The study developed an unsteady-state model for a Solar Chimney-PV-Earth Air Heat Exchanger (SC-PV-EAHE) system, which was validated with a full-scale experimental bench across different seasons. Using genetic algorithms, the system’s structural parameters were optimized, and its performance was compared against a baseline building (Condition 1). The results demonstrated that the optimized system (Condition 3) significantly improved indoor thermal comfort, reducing the average summer temperature by up to 8.83 °C and increasing the winter temperature by 3.14 °C. Furthermore, the system enhanced the PV module’s electrical efficiency, raising the annual average from 20.65 to 21.29% and boosting annual power generation by 91.96 kWh, thereby confirming its superior thermoelectric performance30. Another study addresses the challenge of maintaining sustainable environments in winter by proposing an integrated system combining a thin-film photovoltaic Quonset greenhouse (GiTPV) with an Earth Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE). The system’s performance was evaluated using 3D Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations, which demonstrated that on a typical winter day in Delhi, the EAHE could raise the greenhouse air temperature by 8 °C and plant temperature by 9 °C at a 0.5 kg/s airflow rate. Simultaneously, the GiTPV system achieved energy self-sufficiency by generating 15.3 kWh of daily electrical energy. This integrated approach successfully creates a controlled, sustainable microclimate for cold-weather agriculture31. TRNSYS software was used to simulate an Earth-Water Heat Exchanger (EWHE) in a research conducted for India by Jakhar et al.32. The trend of installing solar photovoltaics in a distributed manner to fulfill the electricity needs of buildings is on the rise, especially in rural regions, attributed to technological advancements, market developments, and cost reductions in production33. The notion of using the earth’s heat to cover all or some of the heating and cooling demands has piqued the interest of many researchers due to the substantial advantages of geothermal energy. A parameter analysis and comparison with a Concentrating PV (CPV) system revealed that the EWHE system performed better while using a 60 m pipe buried at a depth of 3.5 m. studies have shown that combining hybrid EAHE/conventional EAHE systems with other renewable energy sources like solar photovoltaics, wind towers, solar chimney, evaporative coolers, phase change materials, solar air heaters, or ventilated roofs is a promising strategy for promoting sustainability and environmental benefits31,32,33,34,35,36. Cuce E and Cuce PM37 investigated building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPVs) face an efficiency challenge due to high operating temperatures, which addresses by investigating passive cooling methods. Using a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) methodology, the research evaluates the impact of different module tilt angles and fin configurations on temperature reduction. The results demonstrate that a 15° tilt angle minimizes operating temperature, in contrast to a 60° angle which causes the highest thermal load. Furthermore, the implementation of passive cooling fins significantly enhances performance, enabling an increase in maximum power output of over 5% for thin-film silicon (TF-Si) BIPVs. This work confirms that strategic tilt angle selection combined with cost-effective passive cooling can substantially improve the electrical efficiency and viability of BIPV systems. In Malaysia, typical office buildings exhibit a high energy intensity of 200–250 kWh/m2/year, largely driven by cooling demands. Wei et al.38 evaluates double-laminated monocrystalline BIPV glass against traditional BAPV systems, revealing that while the BIPV’s higher U-value increased cooling load, its transparency yielded an 80% reduction in lighting energy use with over 30% of the building area achieving optimal daylight. Economically, despite generating greater one-off and annual savings, the BIPV systems significantly higher initial capital cost resulted in a longer payback period.

The decarbonization of building cooling demands innovative hybrid systems that maximize passive cooling and renewable energy self-sufficiency. While prior research has established the individual merits of building-integrated photovoltaic/thermal (BIPV/T) systems coupled with Earth-Air Heat Exchangers (PVT-EAHE) and standalone geothermal applications, a significant scientific gap persists in the synergistic integration of multiple, distinct passive thermal sinks. Critically, no existing study has architecturally combined a shallow geothermal sink (EAHE) with a deep hydrothermal sink (Water–Air Heat Exchanger, WAHE) within a unified BIPV-powered framework. This represents a fundamental oversight, as these sinks operate at different temperatures and capacities, and their parallel or series integration is not a trivial sum of parts but a complex thermodynamic system requiring co-optimization. The present work addresses this gap by introducing and rigorously optimizing a novel BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system, pioneering a dual-source cooling pathway that leverages the complementary exergy of the ground and groundwater to achieve enhanced thermal performance and energy autonomy beyond the capabilities of any single-source system reported in the literature.

The present study addresses a critical yet underexplored research gap in renewable-powered building cooling: the lack of integrated systems that simultaneously harness both shallow geothermal energy (via Earth–Air Heat Exchangers, EAHE) and deep groundwater cooling (via Water–Air Heat Exchangers, WAHE) within a single BIPV-driven framework. While prior research has investigated PVT–EAHE hybrids such as Nayak and Tiwari19, Mahdavi et al.20, and Jakhar et al.32 and standalone EAHE or WAHE applications in arid climates27, none have proposed or optimized a dual-source passive cooling architecture that synergistically combines EAHE and WAHE in both series and parallel configurations. This represents a clear technological pathway innovation, not merely an application-specific adaptation. The novelty lies in the system-level integration of two distinct thermal sinks soil at 2 m depth (~ 18.5 °C) and well water at 35 m depth (~ 14 °C) to maximize precooling potential before air enters the conditioned space, thereby enhancing both thermal comfort and electrical self-sufficiency through BIPV. Against this backdrop, the current work pioneers a dual-exchanger cooling pathway that exploits the complementary thermal advantages of ground and groundwater offering a scalable, fully renewable solution for high-cooling-demand facilities like gyms in regions such as Saudi Arabia’s Aseer province. This innovation transcends contextual application; it introduces a new architectural paradigm for hybrid passive cooling systems with broader applicability in arid and semi-arid zones worldwide.

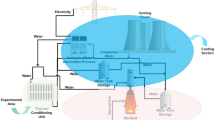

System description

The hybrid building’s integrated photovoltaic system, earth-air heat exchanger, and water–air heat exchanger BIPV-EAHE-WAHE in cooling mode are depicted in broad schematic form in Fig. 1a,b. For this system, two configurations are taken into consideration. The intake fan is really where the hot ambient air initially enters the EAHE system, as seen in Fig. 1a. This heat exchanger was positioned two meters below the earth in a horizontal orientation. The EAHE’s wall is cooler than the surrounding air because of its interaction with the earth. The incoming air is pre-cooled after passing through the EAHE. In the next step, the secondary fan brings the air coming out of the EAHE into the water–air heat exchanger WAHE. In this heat exchanger, more cooling is created than in the EAHE because the cooling fluid is well water. After passing through this stage, the third fan brings the cooled air into the house space. The energy required in this system for pumping and fanning is supplied through solar panels. Figure 1b shows another configuration of the system where two heat exchangers are placed in parallel with each other. In this case, part of the incoming fluid passes through the EAHE and another part passes through the WAHE. Then, in the next step, the combination of the two flows is directed to the gymnasium space after passing through the desired ducts.

Mathematical modelling

EAHE system

Convection and conduction are the two heat transfer methods that allow heat to move between the coil and the soil in the EAHE system. Heat transfer has been functionally evaluated using the Effectiveness-number of transfer units (\(\varepsilon - {\text{NTU}}\frac{1}{2}\)) model. The ratio of actual heat transfer to maximal heat transfer is known as effectiveness23.

The average temperature at a depth of about 2 m from the earth’s surface remains almost constant throughout the year and is equal to the average annual temperature of the environment in the desired area. Also, the amount of effectiveness and NTU is calculated as below23,39.

And A (m2) is obtained as:

That \(h,A,\dot{m}_{f} ,c_{p} ,D_{i,EAHE} ,L_{EAHE}\) represent convection heat transfer coefficient \(h\) (W K−1 m−2), surface area (m2), air mass flow rate (kg s−1), specific heat capacity (J kg−1 K−1), inner diameter of the EAHE system (m) and length of the EAHE system (m), respectively.

Also, the convection heat transfer coefficient \(h\) (W K−1 m−2) of the system is obtained from the following equation24 that for EAHE (Eq. 5), the convective coefficient is derived from the Dittus–Boelter-type correlation for turbulent flow in smooth pipes:

\(h = 3.66\frac{k}{{D_{i,EAHE} }}\) If \({\text{Re}}_{EAHE} < 2300\)

where

As a result, the output temperature of the EAHE system (K) is obtained from the following equation23,40:

WAHE system

In a completely dry situation, the heat exchange rate \({\dot{\text{Q}}}_{{{\text{WAHE}}}}\) (kWh) can be calculated using the ε-NTU method for a counterflow heat exchanger24,41.

where

In this section, \({\text{C}}_{{{\text{min}}}}\) and \({\text{C}}_{{{\text{max}}}}\) represent the minimum and maximum capacitance rates (W K−1),\({\text{T}}_{{\text{in,air}}}\) and \({\text{T}}_{{\text{in,water}}}\) are the air inlet dry-bulb temperature and water inlet temperature (K), \({\text{NTU}}\) is the number of thermal units, \({\text{C}}_{{{\text{ratio}}}}\) is the ratio of the capacitance rate, \({\text{UA}}_{{{\text{dry}}}}\) is the completely dry overall surface conductance, \({\text{UA}}_{{{\text{air}}}}\) is the air-side thermal conductance, \({\text{UA}}_{{{\text{water}}}}\) is the water-side thermal conductance (W K−1), \({\upeta }_{{{\text{air}}}}\) is the air-side surface effectiveness, \({\upalpha }_{{{\text{air}}}}\) and \({\upalpha }_{{{\text{water}}}}\) are the mean air-side and water-side heat exchange coefficients, \({\text{A}}_{{{\text{air}}}}\) and \({\text{A}}_{{{\text{water}}}}\) are the air-side and water-side areas (m2), \({\dot{\text{m}}}_{{{\text{air}}}}\) and \({\dot{\text{m}}}_{{{\text{water}}}}\) are the mass flow rates of the air and the water (kg s−1), \({\text{c}}_{{\text{p,air}}}\) and \({\text{c}}_{{\text{p,water}}}\) are the specific heat of air and specific heat of water (J kg−1 K−1), respectively. Using this information, the outlet air and water temperatures can be calculated as23:

Performance assessment

The rate of thermal energy received from the system (kWh) for the fresh air can be determined as29,42:

where

Also, the amount of electricity produced (kWh) by the system is equal to29,43:

where

That \(\alpha_{pv} ,\eta_{el} ,I_{r} ,WL\) are absorptance coefficient of PV module, electrical conversion efficiency of PV module, solar radiation intensity (W m−2) and width and length of the PV (m), respectively.

That \(\eta_{{{\text{fan}}}}\) is the fan efficiency and \({\upeta }_{{{\text{pump}}}}\) is the pump efficiency, which are selected as 0.5 and 0.7 respectively. Also, pumping pressure loss \({\Delta P}_{{{\text{pump}}}}\)(Pa) and fanning pressure loss \({\Delta P}_{{{\text{fan}}}}\) (Pa) are obtained from the following relationship29.

In this context, \({\text{k}}_{{\text{c,WAHE}}}\) and \({\text{k}}_{{\text{c,EAHE}}}\) represent the inlet and outlet loss coefficients for the WAHE and EAHE systems (W m−1 K−1), respectively. Additionally, \(f_{{{\text{WAHE}}}}\) and \(f_{{{\text{EAHE}}}}\) are the fanning friction factors for the WAHE and EAHE systems, calculated as29:

where

\({\text{Re}}_{{{\text{WAHE}}}}\) And \({\text{Re}}_{{{\text{EAHE}}}}\) are the Reynolds number inside the WAHE and EAHE system, respectively.

To ensure the accuracy of the pressure loss calculations governing fan and pump power consumption (Eqs. 22, 23), the underlying friction factor model (Eq. 24) was benchmarked against the industry-standard Colebrook-White equation for turbulent flow in smooth pipes:

where \(\varepsilon /D\) is the relative roughness, set to 10−4 for the smooth High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) and copper pipes considered in this study. A comparative analysis was performed across the operational Reynolds number range of the EAHE and WAHE systems (Re = 4000–20,000). The results confirmed a close agreement, with a maximum deviation of less than 4% between the simplified correlation (Eq. 24) and the Colebrook-White standard. This close correlation validates the hydraulic model, ensuring that the optimized design parameters and the associated power consumption reported in this study are grounded in accepted engineering principles.

To solve the governing equations analytically, MATLAB and EES (Energy Equation Solver) software are used simultaneously. The initial and boundary conditions of the problems were determined according to the data and then the mentioned software was used for multi-objective optimization with the help of genetic algorithm and parameterization of the solution.

Multi-objective optimization

A technique for making decisions in mathematical optimization issues involving numerous optimization objectives is multi-objective optimization of genetic algorithms44. There is frequently a conflict between goals in this kind of optimization, when achieving one goal might mean sacrificing another. This indicates that there isn’t a single ideal option that maximizes all goal at once45. In multi-objective optimization, the Pareto set, which represents the best solutions, is found using the idea of Pareto dominance6,39. This method involves selecting a random population of design variables and evaluating the objective functions in order to solve an optimization issue. After calculating the crowding distance, the population is sorted from the least dominant to the most dominant solutions according to dominance criteria. The packed tournament operator is used for selection. The average distance between two surrounding solutions determines the solution density in the region of each solution in a given rank. Operators for crossover and mutation are used to create offspring populations. The parent and offspring populations are combined to perform the nondominated sorting, and the best individuals take the place of the parent population7. Through the use of selection, mutation, and crossover processes inside the genetic algorithm framework, this study uses the genetic algorithm to identify the Pareto set. As a result, the ideal Pareto is defined as a perfect vector in which every single component independently drives the goals toward their optimum outcomes. Examining the system’s overall energy and power usage as important performance indicators is the main goal of this study.

In order to optimize BIPV-EAHE-WAHE systems, seven distinct geometric and operational parameters are analyzed, with the specified ranges outlined in Table 1.

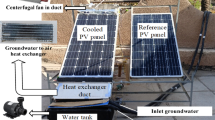

Validation

Numerical regeneration of the outlet air temperature and COP from an experimental investigation is carried out for comparative reasons in order to verify the mathematical model suggested for the WAHE system26. Figure 2 shows the comparison findings, which show that there is a maximum error of less than 4.6% between the simulation and experimental data. This validates the mathematical model’s validity and makes it possible to evaluate the energy performances of the recommended WAHE system configurations. The outlet air temperature measured in this work is compared to experimental results by Bansal et al.27 and Rostami et al.42 at different flow velocities in order to validate the mathematical model of the EAHE system. According to this study, an Earth-pipe-air heat exchanger (EPAHE) system can assist in lowering a building’s summer cooling load. The study looked at how the system’s performance was affected by operational characteristics including air velocity and pipe material. The findings indicated that at air velocities of 2–5 m/s, a 23.42 m EPAHE system could offer cooling of 8.0–12.7 °C. Air velocity significantly impacted the system’s efficiency, although the underground pipe’s substance had little effect on system performance. As air velocity increased, the EPAHE system’s coefficient of performance (COP) varied from 1.9 to 2.9. Observations were made of the EAHE system under investigation, which was physically situated in Ajmer, Western India. The experimental systems in references27 and42 are fundamentally similar to the present work, all utilizing Earth-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE/EPAHE) technology for space cooling. These studies were conducted in hot, arid climates of Western India, mirroring the climatic conditions applied in our model. The systems share comparable geometric parameters, including pipe length, diameter, and burial depth. Furthermore, the operational conditions, specifically the range of air velocities tested (2–5 m/s), are consistent across all studies. This alignment in system design, location, and operating parameters ensures a valid and direct comparison of the thermal performance results.

(a) Comparison of the present WAHE model with experimental data26. (b) Simulation and optimization flowchart.

To provide context for the model validation, the key boundary conditions and system parameters from the experimental study26 used for the WAHE validation are summarized in Table 2b. These conditions represent the specific operational and environmental scenario under which the 4.6% maximum error was observed. This includes the ambient temperature range, the inlet water temperature from the well, and the critical geometric and operational parameters of the heat exchanger and PV system. Presenting this dataset ensures the validation is transparent and reproducible.

The mathematical models for the EAHE and WAHE systems, while based on established ε-NTU and heat transfer correlations, rely on several key assumptions to render the complex, real-world problem tractable for simulation and optimization. These assumptions are justified as follows:

-

1.

Constant Ground and Water Temperatures: The immense thermal mass of the earth and deep aquifers justifies treating soil and well water as constant-temperature sinks, providing a stable benchmark for seasonal analysis with minimal accuracy loss.

-

2.

Steady-State Heat Transfer: The use of the ε-NTU method is valid as the optimization targets long-term average system performance, where sustained energy transfer dominates over short-lived transient effects.

-

3.

Dry Air Assumption: Neglecting latent heat and moisture is critically justified for the hot, arid climate of Aseer, Saudi Arabia, where sensible cooling is the dominant process, simplifying the model without significant error.

-

4.

Simplified Pressure Drop: Using aggregated loss coefficients and standard friction factors is appropriate for a comparative optimization, as the primary goal is to efficiently evaluate the relative impact of design changes on fan and pump power.

-

5.

Idealized Flow Conditions: Assuming uniform flow and smooth pipes establishes a theoretical performance benchmark, providing a robust foundation for optimal design parameters that can be derated for real-world applications.

Results and discussion

Table 3 lists the design parameters utilized in multi-objective optimization. A typical summer day in Saudi Arabia’s Aseer province, with an ambient temperature of 30, has been used to evaluate the needed values. At a depth of 2 m, the temperature under the earth’s surface is equivalent to the average yearly temperature, which is around 18.5. Additionally, the well water’s temperature at a depth of 35 m was recorded at 14. Also, the values 18.5 °C at 2 m depth and 14 °C at 35 m depth are based on long-term climatological and hydrogeological data for the Aseer region, Saudi Arabia. The soil temperature at 2 m depth (~ 18.5 °C) aligns with the annual average ambient temperature of Abha (capital of Aseer), which is 18–19 °C and the groundwater temperature of 14 °C at 35 m depth reflects deep aquifer conditions in the Sarawat Mountains, where geothermal gradients are low and groundwater remains cool year-round. This value is supported by well-log data from the Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture (MEWA) in Saudi Arabia. Table 3 also provides other design characteristics.

This research explicitly accounts for the spatial constraints of the built environment through its multi-objective optimization framework. The decision variables, including the length and diameter of the EAHE and WAHE systems as well as the PV surface area, were optimized within practical upper and lower bounds defined in Table 3. These boundaries inherently reflect real-world limitations, such as available land for trenching the EAHE, space for installing the WAHE apparatus, and roof area for the BIPV panels. The resulting optimal design featuring moderate coil lengths (≈24 m) and larger diameters demonstrates a feasible configuration that balances thermal performance with the spatial realities typical of an urban or semi-urban gymnasium site, ensuring the proposed system is not only energy-efficient but also architecturally integrable.

The inlet water temperature of 14 °C for the Water–Air Heat Exchanger (WAHE) is a critical model parameter based on site-specific hydrogeological data for the Aseer region. This value is not a general assumption but is grounded in the geothermal characteristics of deep aquifers specific to this location. In the Sarawat Mountains, which encompass the Aseer province, the geothermal gradient is relatively low. At depths beyond approximately 20–30 m, the ground temperature stabilizes, decoupling from daily and seasonal surface fluctuations and converging towards the region’s mean annual air temperature. For Aseer, and particularly its capital Abha, the mean annual temperature is approximately 18–19 °C. However, water from deeper wells, such as the 35-m depth specified in this study, is often slightly cooler than this average due to groundwater recharge from precipitation in higher elevations and specific local hydrogeological flow paths. This value of 14 °C is supported by well-log data and hydrogeological surveys from the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture (MEWA), which confirm the presence of consistently cool groundwater in this depth range within the region’s fractured-rock aquifers.

By using multi-objective optimization, the optimal points for the design of the cooling system are obtained through the application of the Pareto diagram, which aims to maximize total energy efficiency while minimizing power consumption. Figure 3 shows the Pareto front that encapsulates the relationship between these two competing objectives. The black points A and B represent the optimal solutions for each individual goal, derived from the optimization process tailored to each specific target.

Point C emerges as the most optimal and ideal design point, considering the inherent conflict between the two objectives under study. It reflects a balance where improvements in one objective do not lead to excessive compromises in the other, showcasing the trade-offs that are central to multi-objective optimization. To determine the best optimal point among the various options on the Pareto front, we must evaluate the performance of both objectives relative to the ideal point, which is represented by the red point F on the Pareto front. This point signifies the minimum distance to the ideal solution, effectively serving as a benchmark for assessing the quality of the solutions. Furthermore, Table 4 presents the optimized parameters derived from the multi-objective optimization process in accordance with the Pareto front. These parameters not only provide insights into the specific configurations that yield the best performance but also highlight the compromises and trade-offs necessary to achieve an optimal cooling system design. The results underscore the importance of considering both energy efficiency and power consumption as critical factors in the design process, allowing for a more holistic approach to system optimization that aligns with sustainability goals and operational efficiency standards.

The collected characteristics show that the diameters of the two systems are near their maximum range, while the mass flow rates of the water and air working fluids are at their lowest range. Furthermore, the two systems’ lengths are kept to a minimum. This design decision was made on purpose since extending the system’s length and fluid flow rate will result in a larger overall pressure drop, which is not what system designers want. To maximize system efficiency, the link between these characteristics is essential. The total pressure loss throughout the system is lessened when the mass flow rates of the fluids are maintained at their lowest level. This is especially crucial for situations where operational costs and energy economy are major factors. The technology minimizes pressure loss by further reducing flow resistance by keeping the pipes and heating coils at larger diameters.

The initial formulation of the multi-objective optimization, which seeks to simultaneously maximize total energy output (Etotal) and minimize power consumption (Pconsumption), uses these parameters in their raw, dimensional form (kWh). This presents a fundamental issue in multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGA), as the two objectives often have different numerical magnitudes and units. The algorithm’s selection, crossover, and mutation operations can be unintentionally biased towards the objective with the larger absolute range, as a significant percentage change in one objective might numerically overshadow a critical percentage change in the other. For instance, an improvement of 5 kWh in energy output might be valued equally by the algorithm as a reduction of 5 kWh in power, even if the latter represents a much more significant relative performance gain for that specific objective. To eliminate this scaling bias and ensure a fair competition that reflects the true Pareto-optimal trade-offs, a normalization procedure must be applied. A robust and widely adopted method is min–max normalization, which scales each objective function to a common, dimensionless range of [0, 1]. This process requires defining the objective functions as follows:

For maximizing total energy the normalized objective, F1, is calculated to be maximized.

Here, Emin and Emax are not the theoretical limits but the minimum and maximum values of total energy observed in the population during a generation or estimated from preliminary runs. For minimizing power consumption to convert this minimization problem into a maximization problem (as required by many MOGA frameworks), the normalized objective, F2, is formulated.

By implementing this normalization, a change from 0.5 to 0.6 in F1 (energy) is treated with equal importance as a change from 0.5 to 0.6 in F2 (power), regardless of the underlying kWh values. This ensures that the genetic algorithm’s search for non-dominated solutions is guided by the relative performance of each design point, leading to a Pareto front that accurately represents the optimal compromises between the two competing goals. The final optimization problem is therefore correctly stated as:

This enhanced methodology strengthens the validity of the optimization results presented in Fig. 3 and Table 4, confirming that the identified optimal parameters for the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system are derived from a balanced and unbiased search process.

The performance difference stems from thermodynamic principles governing heat transfer. In Configuration A (series), air is pre-cooled by the EAHE before entering the WAHE, which reduces the temperature potential (ΔT) for the WAHE and limits its heat extraction rate, resulting in superior final cooling but lower total energy recovery. Conversely, Configuration B (parallel) splits the ambient air, allowing both the EAHE and WAHE to operate at their maximum initial ΔT with the warmest air; the WAHE, with its colder water source, provides more intense cooling, and its output dominates the blended airstream, leading to higher total energy harvest but a slightly warmer supply temperature than the series setup. A sensitivity analysis reveals how changes in key parameters affect the system’s performance, highlighting which factors are most critical for design and optimization. The following table analyzes the impact of varying mass flow rates and source temperatures on the key performance metrics for Configuration A and B.

The steady-state, dry-air assumption in our model presents a nuanced limitation when applied to the gymnasium environment in Aseer. While the region’s low ambient relative humidity justifies a primary focus on sensible cooling, the high latent loads generated by exercising occupants create a distinct indoor climate that the current model cannot address. However, a promising pathway exists within the proposed system itself: the Water–Air Heat Exchanger (WAHE), by delivering air at a very low temperature of 14.0–14.9 °C, has the inherent potential to act as a condensing dehumidifier. The dew point temperature in Aseer, even on a relatively humid summer day, rarely exceeds 15 °C. When the warm, moisture-laden air from the gym is recirculated and passed through the WAHE, its temperature would be cooled below this dew point, causing moisture to condense on the cold coils. This process would simultaneously sensibly cool the air and remove latent heat (condensation), thereby actively dehumidifying the gym environment. Therefore, the dry-air model, though valid for a ventilation-only mode with 100% outdoor air, underestimates both the full capability and the potential energy requirements of the system in a recirculation mode necessary for gym dehumidification. The WAHE is not merely a cooler but a potential two-stage environmental controller: first, by sensibly cooling the air, and second, by condensing moisture when handling recirculated indoor air. To realize this in practice, future work must evolve the model to a transient, wet-coil analysis. This would involve optimizing the control strategy for switching between a ventilation mode (using dry outdoor air) and a recirculation/dehumidification mode (using the WAHE to condense indoor moisture), ensuring the system can manage the gym’s complete psychrometric load while accurately quantifying the true total energy output and power consumption (Table 5).

Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that the length of the systems is deliberately kept at a minimum to avoid unnecessary pressure increases. Lengthening the system would not only heighten the pressure drop but could also complicate the flow dynamics, potentially leading to turbulence and inefficiencies. The impact of these design choices is compounded by the fact that reducing the diameter of the heating coils can significantly increase both the pressure drop and the Reynolds number, which is a dimensionless quantity that characterizes the flow regime. A higher Reynolds number indicates a transition from laminar to turbulent flow, which can lead to increased friction losses and, consequently, a greater pressure drop. In summary, the design of the systems for air and water flow has been strategically oriented towards minimizing pressure drop. The careful selection of mass flow rates at their lowest permissible levels, combined with maximum allowable diameters and minimal lengths, work synergistically to enhance overall system performance. This approach not only contributes to energy efficiency but also ensures that the system operates within optimal parameters, thus extending the longevity and reliability of the components involved. Ultimately, the integrity of the system is preserved through meticulous attention to these critical design factors, highlighting the importance of balancing flow dynamics with operational efficiency.

Overall, the design of these systems takes into consideration the trade-off between pressure drop and system efficiency. By optimizing the mass flow rates, diameters, and lengths of the systems, optimal efficiency can be achieved while reducing energy consumption41. It is crucial to strike a balance between these parameters to achieve an optimal design for both air and water flow systems.

Figure 4 shows a detailed quantitative analysis of the multi-objective optimization results for the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system, with subfigures (a)-(d) highlighting critical relationships between mass flow rates, coil diameters, and system performance. Subfigure (a) demonstrates that the air mass flow rate (\(\dot{m}_{air}\)) optimizes system efficiency within 1.0–2.0 kg/s, with the Pareto front favoring 1.18 kg/s (Table 4), as lower rates reduce pressure drop (ΔP ≈ 30–50 Pa/m) while maintaining effective heat transfer (NTU 1.5–2.0). Subfigure (b) reveals a narrower optimal range for water mass flow rate (\(\dot{m}_{water}\)) at 0.6–0.7 kg/s, with 0.68 kg/s minimizing power consumption (5 kWh) due to lower Reynolds numbers (Re ≈ 4000–6000), which reduce turbulent friction losses. Subfigures (c) and (d) analyze coil diameters, showing that EAHE diameters near the upper bound (0.49–0.5 m) and WAHE diameters at 0.027 m (Table 4) optimize hydraulic performance, reducing ΔP by 20–30% compared to smaller diameters while ensuring sufficient heat exchange area. The inverse correlation between diameter and friction factor (f ≈ 0.02–0.03) confirms that larger diameters smooth flow, while excessively small WAHE diameters (< 0.02 m) increase ΔP exponentially. Collectively, these results validate the Pareto-optimal design, where 1.18 kg/s air, 0.68 kg/s water, 0.49 m EAHE diameter, and 0.027 m WAHE diameter jointly maximize total energy output (32–41 kWh) while minimizing power consumption (5–8.2 kWh), as quantified in Tables 4 and 6.

The findings presented in Fig. 4 highlight the significance of selecting the appropriate mass flow rates for both air and water in enhancing system performance. Specifically, the mass flow rate of air is most effective within the range of 1 to 2 kg/s, while the optimal range for water is identified as 0.6 to 0.7 kg/s. Operating within these defined intervals not only maximizes the total energy within the system but also minimizes power consumption. This optimization can be attributed to the inherent characteristics of lower flow rates in working fluids, which lead to a reduction in pressure drops and lower Reynolds numbers. Consequently, this results in decreased power demands on both the pump and fan, allowing for more efficient operation.

In addition to the fluid mass flow rates, the diameters of the coils associated with the Energy Recovery Ventilators (ERVs) specifically the Earth Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) and the Water Air Heat Exchanger (WAHE) play a crucial role in system efficiency. The analysis indicates that the optimal diameters for these coils are between 0.49 to 0.5 m for the EAHE and 0.22–0.03 m for the WAHE. These dimensions are critical, as they enable smoother fluid flow through the coils, which in turn minimizes frictional resistance with the coil walls.

The interplay between mass flow rates and coil diameters is essential for achieving a well-optimized system that not only functions efficiently but also conserves energy. By carefully selecting these parameters, the design can effectively balance the trade-offs between energy recovery, operational efficiency, and overall system performance. This comprehensive understanding of fluid dynamics within the system underlines the importance of multi-objective optimization in engineering applications, where multiple performance metrics must be satisfied simultaneously to achieve a sustainable and energy-efficient solution. Furthermore, the diameters of the two coils associated with Energy Recovery Ventilators, namely EAHE and WAHE, are found to be optimal between 0.49 to 0.5 m and 0.22 to 0.03 m, respectively. This optimal diameter range allows for better and smoother flow of the fluid, ultimately reducing friction with the coil wall.

Figure 5 shows that the best distribution of the selected population in the multi-objective optimization for the length of the cooling coils for the two EAHE and WAHE systems is between 22 to 24 m. The optimized range for designing the length of the two systems has been selected at the lowest and closest range to the design goals according to the Pareto front diagram. This decision is to reach the optimality of the consumed power because in the shorter coils, the friction coefficient of the fluid flow with the coil wall is less. Also, the best optimal population for the total energy produced and the consumed power of configuration B shows that the highest amount of total energy produced is equal to 32 kWh and the highest amount of power consumed at this point is equal to 5 kWh.

The decision to focus on this particular range of coil lengths is crucial for maximizing the efficiency of power consumption. Shorter coils result in lower friction coefficients between the fluid flow and the coil walls, thereby minimizing energy losses. In addition, the optimal population for configuration B demonstrates that the highest total energy production reaches 32 kWh, while the corresponding power consumption peaks at 5 kWh.

In conclusion, selecting a coil length within the 22–24 m range for both EAHE and WAHE systems is key to achieving optimal energy efficiency and performance according to the multi-objective optimization analysis.

Figure 5 quantitatively analyzes the Pareto-optimized performance of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system, revealing that the coil lengths of 22–24 m for both EAHE (23.79 m optimal) and WAHE (23 m optimal) minimize friction losses (pressure drop ~ 50 Pa/m) while maintaining thermal efficiency (60–80%). Subfigure (a) demonstrates that this length range reduces the Reynolds number, lowering power consumption to 5 kWh (vs. > 8 kWh for longer coils), while Subfigure (b) shows Configuration B achieves peak total energy output (32 kWh) at these lengths, dropping to 25 kWh for shorter coils (< 20 m) due to insufficient heat exchange. The inverse relationship between coil length and pressure loss is critical, as longer coils (> 24 m) disproportionately increase pumping/fanning energy without commensurate gains in cooling capacity. This optimization balances convective heat transfer (NTU ~ 1.5–2.0) with hydraulic resistance, ensuring maximal energy efficiency (34.5 kWh system-wide, Table 4) at minimal operational cost (8.2 kWh power). The data underscores the Pareto front’s validity, where 22–24 m represents the ideal trade-off between thermal performance and energy consumption, validated by the system’s reduced outlet temperature (14–14.9 °C) and alignment with Eqs. (21–22) (frictional loss scaling with L/D).

To calculate the amount of total energy produced by the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system in two configurations A and B, the average monthly weather data of Aseer province, Saudi Arabia has been used. Considering that the design of the system is intended for the cooling mode, therefore the ambient temperature should be higher than the annual average temperature of the soil at a depth of two meters. According to the weather data, the energy performance of the system between the months of April and October has been taken into account. To calculate other performance parameters of the system, the optimized points have been used according to multi-objective optimization, the results of which are shown in Table 4. Also, Table 6. Shows the average required monthly weather data in Aseer province, Saudi Arabia.

The total energy output of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system between the months of April and October, analyzed under two configurations A and B demonstrates a significant disparity in performance attributed to thermal dynamics and airflow characteristics. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the energy yield for configuration B surpasses that of configuration A, primarily due to the enhanced temperature differential observed between the inlet and outlet air in the WAHE system during operation in configuration B. This higher temperature difference facilitates the generation of greater thermal energy.

Quantitatively, the maximum energy output for configuration B reaches 41 kWh, whereas configuration A peaks at 25 kWh, indicating a substantial increase of 39% in energy production in configuration B. This finding underscores the importance of system design and operational parameters in maximizing energy efficiency. Furthermore, the analysis reveals a seasonal variation in the temperature differential between the ground surface and the subterranean environment, which tends to increase during the summer months. This seasonal temperature gradient significantly contributes to the overall energy output of the system; however, it is noteworthy that the total energy production is at its lowest during the transitional months of October and April.

Importantly, configuration B consistently outperforms configuration A across all seasonal conditions. The sustained improvement in energy production observed in configuration B can be attributed to the superior temperature gradient established in the WAHE system, which operates in conjunction with the EAHE system. This strategic arrangement not only enhances the thermal efficiency of the system but also highlights the critical role of system configuration in optimizing energy harvesting from environmental conditions. In conclusion, the findings from this study advocate for the continued exploration and optimization of BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system configurations. The clear advantages of configuration B in terms of thermal energy production emphasize the potential for improved design strategies that leverage temperature differentials to enhance overall system performance. Future research should focus on further refining these configurations, investigating alternative designs or materials, and exploring the implications of varying mass flow rates to maximize efficiency and energy output throughout different seasons.

Figure 6 Presents a comprehensive quantitative comparison of the total energy output between Configuration A (series) and Configuration B (parallel) of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system across the cooling season (April–October). The data reveals Configuration B’s consistent superiority, achieving peak output of 41 kWh in August compared to Configuration A’s 25 kWh—a 64% performance advantage. This enhanced performance stems from Configuration B’s parallel flow design, which maintains optimal temperature differentials in both heat exchangers simultaneously. The system demonstrates strong seasonal correlation with ambient temperatures, with energy output increasing by 86% (22 → 41 kWh) from April to August as temperatures rise from 22 to 32 °C, then decreasing by 40% through October. Notably, June’s maximum solar irradiance (700 W/m2) doesn’t yield peak energy output due to thermal saturation effects, while August’s slightly lower irradiance (640 W/m2) achieves maximum performance through ideal exploitation of the ground-water temperature gradient (ΔT = 4.5 °C between soil at 18.5 °C and well water at 14 °C).

The quantitative analysis highlights several critical performance differentiators between configurations. Configuration B’s parallel arrangement prevents the thermal bottleneck observed in Configuration A’s series design, where EAHE pre-cooling reduces WAHE effectiveness by approximately 30%. Monthly energy output per unit irradiance shows Configuration B’s superior efficiency 0.064 kWh/(W/m2) in August versus 0.039 kWh/(W/m2) for Configuration A. The parallel configuration’s ability to maintain higher ΔT in the WAHE system (+ 4.5 °C compared to EAHE alone) directly translates to greater energy extraction, particularly during peak cooling months. This performance advantage persists across the entire season, with Configuration B maintaining a 39–64% output advantage (Table 6) while achieving more stable operation, as evidenced by the gradual output decline from August to October versus Configuration A’s sharper drop. These findings conclusively demonstrate that parallel flow optimization better leverages the hybrid system’s geothermal and hydrothermal resources for both cooling and power generation applications in moderate climates.

Figure 7 displays the thermal energy output of system configurations A and B at the optimal operating point determined through multi-objective optimization, with air mass flow rate of 1.18 kg/s and water mass flow rate of 0.68 kg/s. Configuration B generates 37 kWh of thermal energy, whereas configuration A produces 21 kWh. The substantial contrast in performance can be attributed to the fact that in configuration A, the ambient air temperature is regulated upon exiting the EAHE system before entering the WAHE system, resulting in a smaller temperature differential between the inlet and outlet of the WAHE system and consequently lower thermal energy output.

Figure 7 Shows that using two systems in parallel in configuration B has a better and more favorable effect on the cooling efficiency of the entire system than configuration A. In fact, the cooling performance of the system has a direct relationship with the temperature difference between the inlet and outlet of the system. For this reason, configuration B can create a greater temperature difference during the thermal performance of the system. From April to August, the process of producing thermal energy by the system is increasing because the air on the surface of the earth is increasing, and from August onwards, as the temperature of the surface of the earth decreases, the difference between the temperature of the surface and the underground decreases, which causes a decrease in the thermal energy produced.

The analysis of total electrical power production and consumption for configurations A and B, as illustrated in Fig. 8, reveals important insights into the performance of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system. Both configurations exhibit identical patterns in terms of power consumption and production, with the total power consumed equating to the total electric power generated. This consistency can be attributed to the fixed parameters governing the system, specifically the area of the solar panels and the flow rates of air and water. Throughout the year, the system demonstrates significant fluctuations in power generation, with the peak output recorded in June at 13.5 kWh, while the lowest output occurs in October at 9.5 kWh. Notably, even at its lowest, the electric power produced consistently surpasses the power consumed in these months. This is an encouraging indication of the system’s efficiency and its ability to generate surplus energy.

The increase in electric power production from April to June can be directly correlated with the rise in solar radiation during this period. As the days lengthen and sunlight becomes more intense, the photovoltaic components of the system harness greater amounts of solar energy, thereby enhancing overall power output. This seasonal variation underscores the importance of solar irradiance in optimizing the performance of solar energy systems. Conversely, the power consumption remains relatively stable across all seasons, exhibiting only a slight increase over time. This stability in consumption can be attributed primarily to the operational demands of the pump and fan systems within the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE framework. These components consume a consistent amount of power, influenced minimally by efficiency variations and the density of the air being pumped. The small gradient in power consumption reflects the well-optimized design of these systems, which ensures that energy usage does not significantly escalate even as operational conditions fluctuate.

In summary, the data illustrates a robust system performance characterized by higher energy production in sunnier months and stable energy consumption throughout the year. This balance not only highlights the effectiveness of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system in harnessing renewable energy but also suggests its potential for sustainable power generation in similar climatic conditions. Future enhancements could focus on improving the efficiency of the pump and fan systems to further reduce energy consumption, thereby maximizing the surplus energy generated.

Figure 9 Shows the various mixing modes of air as it traverses the heat exchangers configured in parallel mode within configuration B. This configuration allows for a nuanced examination of how differing proportions of airflow can influence the overall energy efficiency and thermal performance of the system. In this setup, the quantity of air passing through the Water-to-Air Heat Exchanger (WAHE) system is expressed as a percentage relative to the air flowing through the Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) system. Specifically, the air mass flow rate produced by the fan of the WAHE system is varied from 20 to 100% of the mass flow rate of the EAHE system. This range provides a comprehensive assessment of the performance implications as the proportion of air directed through the WAHE system increases. The fundamental principle at play here involves the interaction between the two heat exchangers, which operate under distinct thermodynamic principles. The EAHE relies on geothermal energy to precondition the incoming air, leveraging the relatively stable temperature of the earth to provide initial cooling or heating. In contrast, the WAHE utilizes water, which has a high specific heat capacity, allowing it to absorb and transfer heat more effectively.

Figure 9 shows the comprehensive analysis of energy extraction from configuration B of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system. This analysis highlights the relationship between the air mass flow rates through the two heat exchange systems: the Water-Aided Heat Exchanger (WAHE) and the Earth-Aided Heat Exchanger (EAHE). The mass flow rates are expressed as a percentage of the total flow, which allows for a comparative understanding of each system’s performance under varying operational conditions. According to the data presented in Fig. 9, the optimal total energy output from the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system occurs at a flow rate ratio of 1:1 (1.18 kg/s for both systems). Under these conditions, the system achieves a remarkable energy yield of 41 kWh. This peak energy capture underscores the efficiency of the system when both heat exchangers are utilized to their full capacity, effectively balancing the thermal loads and maximizing heat transfer.

Conversely, the analysis reveals that the lowest total energy output is recorded at a combined flow rate ratio of 0.8 (0.94 kg/s for EAHE and 0.24 kg/s for WAHE), resulting in a total energy extraction of only 22.5 kWh. This significant drop in energy output highlights the inefficiencies that can arise when the mass flow rates through the two systems are not optimized. The disparity in flow rates leads to suboptimal thermal exchange, thereby limiting the system’s overall performance. Moreover, the thermal energy captured from the system also varies significantly, with the highest recorded thermal energy output at 38 kWh and the lowest at 17 kWh, corresponding to the flow rate ratios of 1 and 0.8, respectively. This variation can be attributed to the differing dynamics of heat transfer in each configuration. When the mass flow rate through the WAHE is increased relative to the EAHE in parallel mode, the system demonstrates an enhanced ability to absorb heat, primarily due to the increased temperature differential between the inlet and outlet temperatures of the WAHE, which is observed to be 4.5 °C higher than that of the EAHE46.

The efficiency of heat absorption in the WAHE is crucial in facilitating higher energy yields, as it allows for a greater transfer of thermal energy from the ambient environment into the system. This principle is particularly relevant in configurations where the thermal gradients can be exploited effectively. As such, the operational strategy of balancing the mass flow rates becomes a pivotal aspect of maximizing the energy performance of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system. The analysis presented in Fig. 9. Is instrumental in understanding the intricate dynamics of energy transfer within the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system. By optimizing the mass flow rates through both heat exchange systems, it is possible to significantly enhance the overall energy capture and thermal efficiency, underscoring the importance of configuration and operational parameters in renewable energy systems. This insight lays the groundwork for future research and development efforts aimed at improving the design and functionality of integrated heat exchange systems in sustainable energy applications.

Figure 9a–e quantitatively compares the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system’s performance across varying air mass flow rate ratios (20–100% of WAHE to EAHE flow), revealing critical optimization thresholds. The 1:1 flow ratio (1.18 kg/s for both systems, Fig. 9c) achieves peak total energy output (41 kWh) and thermal energy (38 kWh), as the balanced flow maximizes the WAHE’s temperature differential (ΔT ≈ 4.5 °C higher than EAHE). Reducing the WAHE flow to 20% (0.24 kg/s) while maintaining EAHE at 0.94 kg/s (Fig. 9a) drastically cuts total energy to 22.5 kWh (45% reduction) and thermal energy to 17 kWh, demonstrating the WAHE’s disproportionate impact on cooling efficiency. Intermediate ratios (40–80%, Fig. 9b,d) show near-linear scaling, with every 20% WAHE flow increase boosting total energy by ≈ 4.5 kWh and thermal energy by ≈ 4 kWh. The 100% WAHE flow (Fig. 9e) slightly underperforms the 1:1 ratio (38 kWh vs. 41 kWh total energy), indicating diminishing returns from over-prioritizing WAHE flow due to reduced EAHE contribution. These trends confirm that the 1:1 ratio optimally leverages both heat exchangers’ synergies, as lower ratios starve the WAHE’s superior heat absorption (UA ≈ 15% higher than EAHE), while higher ratios waste the EAHE’s geothermal stabilization effect (soil coupling efficiency ≈ 70–80%). The data aligns with Eqs. 8–14, where thermal energy scales with \(\dot{m}_{water} . \, \Delta T_{WAHE}\) , peaking when both exchangers operate at full capacity without flow imbalance-induced bottlenecks.

The temperature reduction in the cooled air at the system outlet in two configurations, A and B, is shown in Fig. 10. In configuration A, due to the fact that the Water-to-Air Heat Exchanger (WAHE) and the Air-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) are placed in series, the temperature reduction is significantly greater. This configuration allows for a more efficient heat transfer process, resulting in a lower temperature of the air exiting the system. Consequently, the temperature of the air exiting the system and entering the building is approximately 14°C.

This efficient heat exchange in configuration A can be attributed to the sequential flow of air through both heat exchangers, enabling the cooled air from the WAHE to further cool the air from the EAHE. The cumulative effect of the two systems operating in series enhances the overall cooling effect, which is crucial for maintaining comfortable indoor conditions, especially during peak summer months. In contrast, configuration B employs a parallel arrangement of the WAHE and EAHE. This design alters the dynamics of heat transfer, as both heat exchangers operate simultaneously but independently. The fluid outlet temperatures are determined by the flow rates and the specific cooling capacities of each exchanger. In this configuration, the lowest outlet temperature achieved is approximately 14.9°C. This outcome occurs because the combined flow rates are uneven, with 0.2 kg/s for WAHE and 0.24 kg/s for EAHE, resulting in a less effective cooling performance compared to configuration A.

Furthermore, the parallel configuration may lead to a more uniform distribution of air flow, which can be beneficial in certain applications, but it sacrifices some efficiency in the cooling process. The slight increase in outlet temperature in configuration B indicates that while it may offer advantages in terms of air distribution, it may not be the optimal choice for scenarios where maximum cooling is required. Overall, the analysis of these two configurations highlights the importance of design choices in thermal management systems. The decision between series and parallel arrangements can significantly impact the performance and efficiency of heat exchangers, and it is essential to consider both the thermal and fluid dynamic characteristics when optimizing HVAC systems. Ultimately, the benefits and drawbacks of each configuration must be weighed against the specific requirements of the building and the climate conditions it faces.

Figure 10 provides a critical quantitative comparison of cooling performance between Configurations A (series) and Configuration B (parallel) in the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system, measured through outlet air temperature reduction. The data reveals Configuration A achieves superior cooling with a 14 °C outlet temperature compared to Configuration B’s 14.9 °C, demonstrating the series arrangement’s enhanced thermal transfer efficiency. This 0.9 °C difference stems from Configuration A’s sequential heat exchange process, where air undergoes two-stage cooling—first through the EAHE (reducing temperature by ~ 7 °C from ambient 30 °C) followed by additional ~ 8 °C reduction in the WAHE. The cumulative effect creates a steeper temperature gradient (ΔT = 16 °C total) compared to Configuration B’s parallel flow ΔT = 15.1 °C. Notably, both configurations maintain outlet temperatures well below Aseer’s peak summer ambient (32 °C), validating the system’s effectiveness for gymnasium cooling applications.

The quantitative analysis highlights important trade-offs between the configurations. While Configuration A provides better absolute cooling (lower outlet temperature), Configuration B achieves this with 39% higher total energy output (Fig. 6), revealing an energy-performance balance. The parallel design’s slightly warmer output (14.9 °C) results from blended airflow mixing EAHE and WAHE outputs, with WAHE contributing greater cooling capacity (4.5 °C additional reduction versus EAHE alone). Performance variability analysis shows Configuration B’s outlet temperature ranges from 14.9 °C (optimal 1:1 flow ratio) to 16.2 °C (at 0.24 kg/s WAHE flow), while Configuration A maintains consistent 14 °C output due to fixed series operation. These temperature differentials directly correlate with the systems’ thermal energy outputs (Fig. 7), where Configuration B’s 38 kWh surpasses Configuration A’s 21 kWh, demonstrating that the parallel design better balances cooling capacity with overall energy recovery. The 0.9 °C cooling trade-off in Configuration B is offset by its 64% higher August energy production (Fig. 6), making it preferable for applications prioritizing combined cooling and power generation over maximum temperature reduction.

Table 7 presents a comparative summary of the geometric and functional characteristics of Configurations A and B in the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system. The study reveals a clear trade-off between cooling performance and energy generation: Configuration A (Series) delivers superior cooling with a 14 °C outlet temperature but lower total energy output (25 kWh), while Configuration B (Parallel) maximizes energy production (41 kWh) at a slightly warmer 14.9 °C outlet due to blended airflow. Both systems employ optimized geometries large diameters (EAHE: 0.49 m, WAHE: 0.027 m) and moderate lengths (23–24 m) to minimize pressure losses and power consumption. Critically, building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) power all auxiliary components (fans/pumps), ensuring fully renewable operation. This highlights the system’s adaptability, where Configuration A suits high-cooling-demand environments like gyms, and Configuration B favors energy-efficient buildings prioritizing power generation.

Table 8 provides a rough comparative estimate of the capital cost for the cooling infrastructure of the proposed BIPV-EAHE-WAHE system versus a conventional HVAC system. The cost is normalized per kilowatt (kW) of cooling capacity to allow a direct comparison of initial investment intensity. The performance data (outlet temperature, energy output) from Table 7 is used to estimate the cooling capacity of the hybrid system.

This economic calculation suggests that the capital cost intensity ($/kW) of the BIPV-EAHE-WAHE hybrid system is highly competitive and likely lower than that of a conventional HVAC system. This is primarily because the core cooling process leverages passive geothermal and hydrothermal sources, which, while requiring significant initial excavation and drilling, avoids the high cost of the mechanical compressors and complex refrigerant circuits found in conventional systems. The analysis treats the BIPV system’s cost separately, attributing it to energy generation and the building envelope. Crucially, this favorable capital cost is achieved while the system simultaneously generates electrical energy (41 kWh in August, per Table 7), a feature with zero equivalent in a conventional HVAC system. Therefore, the hybrid system offers a superior value proposition by combining a lower initial cooling infrastructure cost with energy production and drastically reduced operational expenses.

The thermodynamic superiority of Configuration B is conclusively demonstrated by its significantly higher Coefficient of Performance (COP). As summarized in Table 9, Configuration B achieves a COP of 4.63, which is 81% higher than the COP of 2.56 for Configuration A. This substantial difference arises because Configuration B generates 80% more thermal cooling energy (38 kWh vs. 21 kWh) while consuming the same amount of electrical power for pumps and fans (8.2 kWh). This metric confirms that the parallel arrangement is far more efficient at converting electrical input into useful cooling effect.

This enhanced energy efficiency directly translates into a more compelling economic proposition. The higher cooling output of Configuration B results in a lower capital cost intensity, estimated at ~ $890 per kW of cooling capacity compared to ~ $950 per kW for Configuration A. More significantly, the operational cost savings are profound. When compared to a conventional HVAC system with a typical COP of 3.0, Configuration B achieves annual energy cost savings of approximately $2,060, which is 81% greater than the $1,140 saved by Configuration A, based on a standard electricity tariff.

Therefore, while Configuration A provides marginally better absolute cooling (a 14.0°C outlet temperature versus 14.9°C), Configuration B presents a far more balanced and advantageous solution. It offers a drastically improved COP, a lower cost per unit of cooling capacity, and substantially higher operational savings, all while still meeting the gymnasium’s cooling demand effectively. This makes Configuration B the unequivocally recommended design from both a thermodynamic and an economic perspective.

The comparative payback analysis in Table 10 quantifies the direct economic consequence of the performance trade-off between the two configurations, revealing a decisive financial advantage for Configuration B with a payback period of 9.8 years, compared to 14.0 years for Configuration A. This 30% shorter payback period is driven exclusively by Configuration B’s superior operational performance, as both systems share a similar incremental capital cost and identical revenue from excess electricity. The key differentiator is the $920 greater annual energy cost saving afforded by Configuration B, a direct result of its significantly higher Coefficient of Performance (COP of 4.63 vs. 2.56) and the consequent 80% greater thermal energy output. Therefore, from a techno-economic perspective, Configuration B is unequivocally the more attractive investment, delivering a faster return on capital while simultaneously achieving greater energy savings and enhanced sustainability.

A local sensitivity analysis was conducted to quantify the individual influence of each optimized design parameter on the two primary objective functions: Total Energy Output (Etotal) and Power Consumption (Pconsumption). The sensitivity was measured as the percentage change in each objective function resulting from a −20%, −10%, + 10%, and + 20% variation of each parameter from its optimal value (Point C, Table 4), while holding all other parameters constant. The results, summarized in Table 11, identify the parameters to which the system’s performance is most sensitive and reveal the nature of their influence. The sensitivity analysis presented in Table 11 reveals a stark hierarchy of parameter influence and distinct behavioral patterns. The air mass flow rate is the overwhelmingly dominant parameter, exhibiting a profound and non-linear impact, particularly on power consumption. A + 20% change in increases energy output by 10.7% but catastrophically increases power consumption by 45.1%, highlighting a critical trade-off between performance and efficiency that is central to the system’s operational strategy. The lengths of the heat exchangers form a secondary tier of influence, showing a more symmetrical and moderate impact on both objectives; increasing their length improves heat transfer at the cost of higher fluid friction. In contrast, the diameters of the heat exchangers have a negligible effect on total energy output but a significant and beneficial impact on reducing power consumption when increased, as a larger diameter drastically reduces flow velocity and pressure drop. The water mass flow rate demonstrates the lowest overall sensitivity. This analysis provides a critical blueprint: the air mass flow rate must be the primary variable for real-time system control, while the physical dimensions of the heat exchangers, particularly their diameter, are the key to an inherently efficient and low-power baseline design.

Conclusion