Abstract

Partial range of focus (ROF) intraocular lenses (IOL) offer excellent distance and intermediate visual acuity, but usually limited distance-corrected near visual acuity (DCNVA). We evaluated the characteristics of eyes implanted with two specific ROF IOL and very good DCNVA. We conducted a prospective, observational, cross-sectional study. Patients implanted with a ROF IOL were visited 1–3 months after uneventful phacoemulsification. We determined mono/binocular, corrected/uncorrected visual acuities (VA) at far, intermediate and near distance; photopic pupil diameter, corneal asphericity, aberrations (RMSHOA, Z4− 0), and axial length (Pentacam® AXL Wave; Oculus, Germany); and implanted IOL power. Monocular DCNVA was stratified in tertiles, with eyes in the first (better DCNVA) compared to the others (standard DCNVA). Univariate and multivariate generalized estimating equations models were used to compare the features of both groups. One-hundred eyes from 50 patients (mean age 69.0 years [SD 8.7], 66.0% female) were enrolled. Monocular distance logMAR VA was 0.00 (0.04) and DCNVA was 0.37 (0.15). Only younger age (66.4 vs. 71.0 years), smaller pupil (2.81 vs. 3.04 mm), and better distance VA (0.00 vs. 0.02 logMAR) were associated with better DCNVA. Therefore, a better distance-corrected VA, smaller photopic pupil diameter and younger age favored better DCNVA with the tested ROF IOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Partial range of focus (ROF, previously known as extended depth of focus or EDOF) intraocular lenses (IOL) provide an extended focus at far that reaches intermediate distances1. According to the standard ISO 11979-7: 20242,3, these lenses must provide a mean distance-corrected visual acuity (DCVA) ≤ 0.1 logMAR (equivalent to ≥ 20/25 Snellen) and a mean distance-corrected intermediate visual acuity (DCIVA) at 66 cm ≤ 0.2 logMAR (20/32). The ISO does not provide a specific criterion for distance-corrected near visual acuity (DCNVA)3. As such, these lenses provide excellent visual acuity at far and good intermediate vision, and patients show functional acuity at near. 3 In addition, ROF IOL induce a degree of dysphotopsia that seems not significantly greater than that perceived by patients with monofocal IOL4. These characteristics may explain their wide market penetration in recent years5.

In the registration studies leading to approval of one of the most widely used ROF IOL, the AcrySof® IQ Vivity® (Alcon Healthcare, US), the binocular DCNVA was 0.31 (Bala et al.6) and 0.25 logMAR (McCabe et al.7), close to 20/40. The standard deviation reported in those studies was larger for DCNVA (0.16 and 0.12) than for either DCVA or DCIVA (0.09 and 0.13 in Bala6, 0.08 and 0.09 in McCabe7, respectively). In the case of the PureSee®, the new ROF IOL by Johnson & Johnson, Corbett et al. found a monocular DCNVA was 0.37, again with larger variation in visual acuity at near (standard deviation of 0.10) than at far and intermediate distances (0.08)8. Similar results for monocular DCNVA have been reported for other ROF IOL9,10. This suggests that DCNVA is more variable than either far or intermediate visual acuity with ROF IOL, and that some patients may obtain a very good DCNVA while others will not. The reasons for this variability are unknown, but their identification would advance our understanding of the characteristics that determine near vision.

This study aims to determine the factors that contribute to a better DCNVA in patients implanted with ROF IOL. The findings may explain general characteristics that determine good visual acuity at near distances with these lenses.

Results

We included 100 eyes of 50 patients. Their characteristics are shown in Table 1 and reflect the usual population undergoing cataract surgery with implantation of a ROF IOL. In this series, 62% of the implanted ROF lenses were AcrySof® IQ Vivity® (Alcon Healthcare, US) and 38% were PureSee® (Johnson & Johnson, US). A summary of the performance of each IOL is provided in Supplementary Material Table 1.

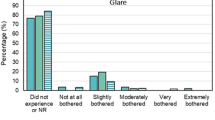

The main endpoint, monocular post-surgery DCNVA, showed a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk p-value = 0.07), with a slight right skewness (Fig. 1). The mean DCNVA (SD) was 0.37 (0.15) and the median (IQR) was 0.33 (0.22) logMAR, approximately 20/40 Snellen. 13% of eyes reached DCNVA ≤ 0.2 logMAR (≥ 20/32).

The first tertile (eyes with “good DCNVA”) included eyes with DCNVA values ranging from 0.00 to 0.30 logMAR, while the “standard DCNVA” included the rest of the eyes, with DCNVA between 0.32 and 0.76 logMAR.

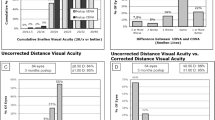

The distribution of values of the variables potentially associated with DCNVA is shown in Fig. 2, while Supplementary Material Fig. 1 shows the relationship of each parameter with DCNVA by IOL. Table 2 shows the comparison between both groups irrespective of the fact if the eyes belonged to the same or a different participant. Patients with good DCNVA were younger (66.4 vs. 71.0 years-old, p = 0.054) and had a smaller pupil in photopic conditions (2.81 vs. 3.04 mm, p = 0.053). No other relevant differences were found.

The role of the different factors on DCNVA is shown in Table 3 after the use of GEE on univariate and multivariate models. The results suggest that younger patients, with a smaller pupil and a better DCVA have a higher odds ratio (OR) of having good DCNVA. On multivariate analyses, a smaller pupil (OR = 0.40 for each mm, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.03; p = 0.058) and younger age (OR = 0.94 for each year, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.00; p = 0.076) had a borderline statistical significance. The other factors did not show a statistical association with DCNVA.

There were no statistically significant differences in the percent of eyes with good DCNVA between the AcrySof® IQ Vivity® (41.9%, n = 62) and the PureSee® IOL (44.7%, n = 38), p = 0.84. The results for each IOL type (Supplemental Material Tables 2 and 3) were similar to those reported for the whole group (Tables 2 and 3) except for the mean age in patients in the PureSee® IOL, who were slightly older for eyes with the good DCNVA (69.4 vs. 67.8 years, p = 0.61). There were no differences between IOL in the multivariable model (p = 0.95; Supplemental Material Table 3) or on interaction tests (p ≥ 0.18, Supplemental Material Table 4)11 either11. Similarly, we compared the results between the extreme tertiles: the first, with “Good DCNVA”; and the third, with “Poor DCNVA” (Supplemental Material Tables 5 and 6). The results were similar to those described for the overall sample, with the exception that the association between DCVA and DCNVA was weakened.

Discussion

These results showed some of the factors that have an influence on DCNVA in patients bilaterally implanted with a ROF IOL. In this study DCVA, age and photopic pupil size emerged as important factors for DCNVA, while sex, axial length, Q, RMSHOA and Z4 − 0 aberrations, and IOL power did not.

The factors analyzed were selected due to their possible influence on DCNVA. Age and sex influence many biological processes. DCVA can be related to DCNVA. Pupil diameter has an influence on depth-of-focus (and, therefore, on resolution), and in this study it was measured in photopic conditions, a proxy for the miotic pupil size in near vision. Higher order aberrations as quantified through total ocular RMSHOA and Z4 − 0 influence visual quality, and they were measured at the photopic pupil diameter to mirror more closely the conditions of near vision. Asphericity was included because it is related to spherical aberrations12 although its relationship with visual acuity is more debatable13. Finally, IOL power was selected because it was hypothesized that small forward movement of a highly positive IOL lens may provide better DCNVA, and the additional power of the lens may be more effective in eyes with a smaller cornea-IOL distance, such as that seen in highly hyperopic eyes14.

The participants in our study are largely representative of patients implanted with ROF IOL in demographic, anatomical and clinical features (Table 1). And even though DCNVA is exposed to more variability than DCVA (possibly due to a larger impact of slight variability of test distance as compared with 4–6 m tests and to changes in ambient light conditions through fluctuations in pupil diameter), our results are similar to those reported in the literature. For example, in the AcrySof® IQ Vivity® registration studies, monocular DCNVA were 0.416 and 0.367 logMAR, and in the study by Corbett with the PureSee® IOL it was 0.378, the same that in the present study. Of note, a recent study with the PureSee® IOL reported a better monocular DCNVA, 0.25 (0.15, from the defocus curve)15 with tolerance to slight defocus15,16. Binocular photopic DCNVA with the Vivity® IOL improved to 0.30 (0.316 and 0.257 in other studies). No studies have published the binocular DCNVA with the PureSee® IOL so far. Therefore, our results are potentially applicable to other patients with ROF and have external validity.

This study found a relationship between younger age and better DCNVA. This relationship may be mediated by a general better visual acuity in the young. In fact, there was also a correlation between age and DCVA (r = + 0.35, p = 0.0003), supporting the fact that elderly patients may obtain less optimal results after surgery.

We also found an association between DCVA and DCNVA on univariate analyses. This association is expected since both evaluate the maximum resolution capacity at high contrast, albeit at different distances. However, their Pearson correlation coefficient was modest at best, r = + 0.15 (p = 0.15). While positively correlated, the low correlation suggests that they are relatively independent and that they are driven by different factors. Uncorrected refractive error, accommodation/presbyopia status and retinal disorders may account for some of the differences between them, but they were eliminated by proper refraction, lens removal and eligibility criteria, respectively. The use of different distance and near charts, as well as illumination conditions and IOL properties, may explain the modest correlation despite their association in models accounting for subject-level characteristics.

A smaller photopic pupil diameter also increased the odds of having better DCNVA (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.98, p = 0.028; Table 2) independent of IOL model (p = 0.95, see Supplemental Material Table 3). The AcrySof® IQ Vivity® allows a better DCNVA because the transition zones that elongate and shift anteriorly the wavefront have a 2.2 mm diameter, which is smaller than the photopic pupil diameter observed in more than 90% of eyes in this study, and its design allows for full light utilization. The PureSee® IOL elongates the focus range by providing a continuous power profile with higher power in the central zone. In both cases, a smaller pupil increases the depth of focus while decreasing HOA (Supplemental Material Fig. 2). An optical bench study has shown that higher apertures (larger pupil sizes) degrade the optical quality of both IOL (in the case of Vivity®, with the Clareon® material) and decrease the extension of the depth-of-focus of the primary peak on the modulation transfer function curves17. Jeon et al. evaluated the uncorrected near visual acuity (UNVA) with the AcrySof® IQ Vivity®18. A smaller (photopic) pupil was associated with better UNVA too, but not with visual acuity at other distances. Small pupils can worsen near visual acuity with multifocal IOL18.

Interestingly, younger age, better DCVA and small photopic pupil diameter were associated with better DCNVA on univariate (p ≤ 0.05, upper rows in Table 3) but not on multivariate (p ≥ 0.058, lower rows in Table 3) analyses. However, the odds ratios were further away from 1.0 (the value of no association) on multivariate than on univariate analyses. These results suggest that these variables are indeed important on DCNVA, but that the model struggled to dissect their true effect, as noted by the wide 95% confidence intervals on adjusted analyses. A homogeneous and relatively modest sample size may account for that. In fact, patients undergoing the pre-operative evaluation are not offered “premium” lenses (ROF, trifocals) if they do not meet stringent eligibility criteria. For example, they are not good candidates if they present a wide or irregular distribution of total corneal refractive power19 because of the potential induction of post-surgery dysphotopsia. Additionally, little variability in the diameter of the photopic pupil not only affects its assessment on DCNVA, but also decreases an already low value of aberrations, potentially neglecting their effect. The result is a relatively homogeneous sample of patients, which despite being representative of the characteristics of patients in which ROF IOL are implanted, makes dissection of the role of individual factors on DCNVA complex. Other factors include the correlation between age and pupil diameter, which induced a modest degree of multicollinearity (variance inflation factor 14.7), increasing the confidence intervals. Measurement error may also attenuate the relationship with DCNVA20, and this may include visual acuity and particularly pupil size determinations. Future studies may actually measure pupil size during near activities rather than using its diameter derived from photopic conditions as a proxy.

No other measured factors influenced DCNVA in the present study. In the Monofocal Extended Range of Vision (MEROV) study, 10% of eyes implanted with a monofocal IOL achieved an unaided near visual acuity ≤ 0.3 logMAR (20/40)21. Smaller pupils, low myopic spherical equivalents, lower Z4 − 0 and shorter axial lengths increased the chances of pseudoaccommodation. The percentage of eyes achieving this DCNVA in the present study was 33.1%, and therefore pseudoaccommodation played a minor role in DCNVA. A shorter axial length (as determined here by a higher IOL power, with a r = – 0.91, p < 0.0001) and lower Z4 − 0 did not have a relevant influence on DCNVA in this study. This was possibly observed because spherical aberration was already low before surgery given the strict eligibility criteria for ROF IOL candidates and also because Z4 − 0 were measured afterwards in photopic conditions, minimizing their potential influence22. There were no differences between IOL models, either (p-value for interaction ≥ 0.56). Indeed, a recent study suggested a similar performance between these two lenses under different optical scenarios using in vitro models22. On the other hand, other studies found a higher depth-of-focus or accommodative range in presbyopic patients implanted with a monofocal IOL with higher corneal spherical aberrations23,24,25 or coma26,27. Using an adaptive optics visual simulator to emulate ROF visual acuity in pseudophakic patients implanted with monofocal IOL, Tabernero et al.28 found that spherical aberration increases generally increased depth-of-focus (4.5 mm pupil), with variable results for increasing levels of aberrations. In another study, induction of negative Z4 − 0 (at 6.0 mm) resulted in higher depth-of-focus in some IOL types, like those with zero-spherical aberration29. Even controlled increases in chromatic aberration improved the depth-of-focus in patients with monofocal IOL30. While these studies demonstrate that modulation of aberrations can increase the depth-of-focus in pseudophakic eyes, the different pupil diameters and the focus of the present study on DCNVA make comparisons difficult.

Regarding Q, our hypothesis was that it may affect DCNVA through its influence on aberrations. Given that RMSHOA and Z4− 0 were not associated with near visual acuity, it is not surprising that we did not find a relationship either between Q and DCNVA. In line with these results, there is no relationship between asphericity and DCIVA after implantation of the Clareon® monofocal IOL using mini-monovision31 or after wavefront-guided laser surgery32.

The practical implications of this study are two-fold. On one hand, the study highlights clinical factors associated with good DCNVA as well as those that are not, which may guide further basic research in IOL design. On the other hand, they may assist in the selection of patients who may be eligible for a ROF IOL. A young patient with excellent DCVA and a small photopic pupil may be a good candidate for implantation of a ROF IOL if relatively good near visual acuity is desired and if there are relative contraindications for implantation of a trifocal lens.

This study has some limitations. These include a moderate sample size particularly for the study of subgroups based on IOL model, which should be interpreted with caution. It evaluated the factors driving DCNVA measured post-surgery, but this does not imply that these factors before surgery are able to predict post-phacoemulsification DCNVA. Other studies need to be conducted to address this issue33. On the other hand, the definition of good DCNVA was derived from the tertiles obtained in this sample (a cut-off of 0.3 logMAR), but another cut-off could have been selected; a consensus on which level of monocular DCNVA represents “good DCNVA” should be defined to standardize this kind of studies. Also, these results apply to monocular DCNVA; while binocular DCNVA is arguably more relevant to patients, monocular visual acuity is related to quality of life and allowed to investigate ocular-level factors, like pupil size or aberrations. The photopic pupil size measured with Pentacam® AXL Wave may not match the actual near pupil diameter. In addition, we determined DCNVA at 40 cm but we did not measure defocus curves, which allow a more comprehensive evaluation of performance at different distances. In future studies, the use of areas under the defocus curve at near may complement the qualitative data derived from this assessment. Finally, it is unclear if these results apply to other ROF lenses. Future research to determine the factors that drive DCNVA after IOL implantation may include larger samples with a wider range of ocular characteristics (larger age range, higher RMSHOA or Z4− 0, etc.). While this may not be appropriate for studying DCNVA in ROF, it may be feasible with monofocal lenses.

In summary, after uneventful implantation of a ROF IOL, younger age, smaller photopic pupil size and DCVA were associated with better DCNVA. These results apply to eyes implanted with the AcrySof® IQ Vivity® or PureSee® IOL with low aberrations at baseline, which are the candidates for these lenses. Determining the role of these and other factors on DCNVA before surgery may contribute to understanding the characteristics that drive near visual acuity and to improve counseling to optimize outcomes of this procedure.

Methods

Design

A prospective, observational study with a cross-sectional analysis between 1 and 3 months after surgery conducted at OMIQ Research facilities in Barcelona (Spain) between October 2024 and April 2025. Researchers adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Quirón Salud Ethics Committee (Sant Cugat del Vallès, Barcelona) approved the study, and all participants signed an informed consent after explanation of the nature and potential consequences of their participation in the study.

Eligibility criteria

Females or males aged 18 years or older with in-the-bag bilateral implantation of an ROF IOL (any model commercially available in Spain) after uneventful phacoemulsification, and able to conduct a follow-up visit one to three months after the surgery of the second eye were potentially eligible.

Patients were excluded if there was any intra or post-surgery complication or adverse event determined in the follow-up visits after standard refraction and visual acuity measurements with the optometrist, and intraocular pressure, and anterior and posterior segment exam (including optical coherence tomography) by an ophthalmologist; had anterior or posterior segment disease; previous refractive or intraocular surgery; ocular traumatism; or any systemic diseases that could hamper proper testing (i.e., Alzheimer’s disease).

In addition, patients were not operated in the first place if they had irregular astigmatism, a pre-operative Root Mean Square value for high-order aberrations (RMSHOA) > 0.300 μm, a power distribution on the sagittal map > 3D, anterior or posterior segment disease (i.e., keratoconus, age-related macular degeneration, etc.), or a history of previous corneal/intraocular surgery or significant traumatism in either eye.

Intraocular lenses

The ROF models implanted in all cases were the AcrySof® IQ Vivity® (Alcon Healthcare, US) and the TECNIS PureSee® IOL (Johnson & Johnson, US). The material of both lenses is hydrophobic acrylic. The AcrySof® IQ Vivity® model has a nondiffractive design that uses the so-called X-WAVE technology, based on two smooth transition elements on the front surface of the IOL6. One delays the central portion of the wavefront as it crosses the IOL compared to the more peripheral wavefront. The other displaces anteriorly the wavefront, resulting in its stretching and an increased focal range. On the other hand, the PureSee® IOL uses a purely refractive design that changes the optical power across the lens, with increases in primary and secondary spherical aberrations34 that may increase depth of focus, an aspheric anterior surface that compensates the average corneal spherical aberration and a refractive posterior surface15.

Methods

A complete ophthalmic visit was conducted between one and three months after surgery. This included determination of photopic, high-contrast monocular and binocular, distance-corrected and uncorrected far (4 m), intermediate (66 cm) and near (40 cm, DCNVA) visual acuity using ETDRS (Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study) charts and measured in the logMAR scale. Then, a complete exam with the Pentacam® AXL Wave (Oculus, Germany) was performed to determine the photopic pupil diameter (with 327 lx at the corneal plane, which according to the BS EN 12464-1: 2021 corresponds to a typical well-illuminated office and is a proxy for the pupil diameter in near reading conditions), corneal asphericity (Q), total eye aberrations (RMSHOA) and spherical aberration (Z4− 0). Also, an optical coherence tomography with the Spectralis HRA + OCT® (Heidelberg Engineering, Germany) was done to evaluate the macular area. Finally, anterior and posterior segment exams and intraocular pressure using Goldman applanation tonometry were conducted to confirm that no ocular adverse events were present. In addition, axial length measurements before surgery and photopic pupil diameter, Q, and aberrations at the photopic pupil size (RMSHOA and Z4− 0) post-surgery as measured with the Pentacam® AXL Wave (Oculus, Germany) and the power of the IOL implanted were collected.

Statistical analysis

The sample characteristics were described using the mean (standard deviation, SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) value for quantitative variables (depending on their distribution), and n (percentage) for categorical variables.

The main endpoint, the monocular DCNVA, was stratified in tertiles. The first tertile represented eyes with “better DCNVA”; the second and third tertiles were considered as eyes with “standard DCNVA”. The collected features (age, sex, distance-corrected visual acuity, axial length, photopic pupil size, Q, power of the implanted IOL, RMSHOA, and Z4 − 0) were compared between the two groups. Also, univariate and multivariate generalized estimating equation (GEE) models, that account for the correlation between eyes of the same patient35, were applied with a binomial family and an exchangeable correlation structure, to determine variables associated with better DCNVA. The variables included in the multivariable model were selected based on their statistical significance in the univariate models. An exploratory analysis was also conducted by lens model.

The results were analyzed using Stata IC 15.1 (StataCorp, USA). A two-tailed p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Savini, G., Schiano-Lomoriello, D., Balducci, N. & Barboni, P. Visual performance of a new extended depth-of-focus intraocular lens compared to a distance-dominant diffractive multifocal intraocular lens. J. Refractive Surg. 34, (2018).

Ribeiro, F. et al. Should enhanced monofocal intraocular lenses be the standard of care? An evidence-based appraisal by the ESCRS functional vision working group. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 50, 789–793 (2024).

Ribeiro, F. et al. Evidence-based functional classification of simultaneous vision intraocular lenses: seeking a global consensus by the ESCRS functional vision working group. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 50, 794–798 (2024).

Guarro, M. et al. Visual disturbances produced after the implantation of 3 EDOF intraocular lenses vs 1 monofocal intraocular lens. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 48, 1354–1359 (2022).

Rampat, R. & Gatinel, D. Multifocal and extended Depth-of-Focus intraocular lenses in 2020. Ophthalmology 128, (2021).

Bala, C. et al. Multicountry clinical outcomes of a new nondiffractive presbyopia-correcting IOL. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 48, (2022).

McCabe, C. et al. Clinical outcomes in a U.S. Registration study of a new EDOF intraocular lens with a nondiffractive design. J Cataract Refract. Surg. 48, (2022).

Corbett, D. et al. Quality of vision clinical outcomes for a new fully-refractive extended depth of focus intraocular lens. Eye 38, 9–14 (2024).

Lesieur, G. & Dupeyre, P. A comparative evaluation of three extended depth of focus intraocular lenses. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 33, (2023).

Iradier, M. T., Cruz, V., Gentilew, N., Cedano, P. & Piñero D. P. Clinical outcomes with a novel extended depth of focus presbyopia-correcting intraocular lens: pilot study. Clin. Ophthalmol. 15, (2021).

Pocock, S. J. et al. Issues in the reporting of epidemiological studies: A survey of recent practice. British Med. J. vol. 329 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38250.571088.55 (2004).

He, J. C. Theoretical model of the contributions of corneal asphericity and anterior chamber depth to peripheral wavefront aberrations. Ophthalmic Physiol. Optics 34, (2014).

Tuan, K. M. A. & Chernyak, D. Corneal asphericity and visual function after wavefront-guided LASIK. Optometry Vis. Sci. 83, (2006).

Savini, G. et al. Influence of the effective lens position, as predicted by axial length and keratometry, on the near add power of multifocal intraocular lenses. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 42, (2016).

Alfonso-Bartolozzi, B. et al. Optical and visual outcomes of a new refractive extended depth of focus intraocular lens. J. Refract. Surg. 41, e333–e341 (2025).

Alarcon, A. et al. Optical and clinical simulated performance of a new refractive extended depth of focus intraocular lens. Eye 38, 4–8 (2024).

Niknahad, A. et al. Evaluation of Clareon vivity and puresee intraocular lenses: optical quality, depth of focus and misalignment effects. Sci. Rep. 15, 26943 (2025).

Jeon, S., Choi, A. & Kwon, H. Analysis of uncorrected near visual acuity after extended depth-of-focus AcrySof® Vivity™ intraocular lens implantation. PLoS One 17, (2022).

Roh, H. C., Chuck, R. S., Lee, J. K. & Park, C. Y. The effect of corneal irregularity on astigmatism measurement by automated versus ray tracing keratometry. Medicine (United States) 94, (2015).

Liu, K. Measurement error and its impact on partial correlation and multiple linear regression analyses. Am. J. Epidemiol. 127, (1988).

Nanavaty, M. A., Mukhija, R., Ashena, Z., Bunce, C. & Spalton, D. J. Incidence and factors for pseudoaccommodation after monofocal lens implantation: the monofocal extended range of vision study. in Journal Cataract Refractive Surgery 49 (2023).

Stern, B. & Gatinel, D. Impact of Pupil Size and Corneal Aberrations in Three Refractive Extended-Depth-of-Focus Intraocular Lens Technologies. In ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract (2025).

Hickenbotham, A., Tiruveedhula, P. & Roorda, A. Comparison of spherical aberration and small-pupil profiles in improving depth of focus for presbyopic corrections. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 38, (2012).

Rocha, K. M., Vabre, L., Chateau, N. & Krueger, R. R. Expanding depth of focus by modifying higher-order aberrations induced by an adaptive optics visual simulator. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 35, (2009).

Rocha, K. M., Soriano, E. S., Chamon, W., Chalita, M. R. & Nosé, W. Spherical Aberration and Depth of Focus in Eyes Implanted with Aspheric and Spherical Intraocular Lenses. A Prospective Randomized Study. Ophthalmology 114, (2007).

Nishi, T. et al. Effect of total higher-order aberrations on accommodation in pseudophakic eyes. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 32, (2006).

Song, I. S., Kim, M. J., Yoon, S. Y., Kim, J. Y. & Hungwon, T. Higher-order aberrations associated with better near visual acuity in eyes with aspheric monofocal IOLs. J. Refractive Surg. 30, (2014).

Tabernero, J. et al. Depth of focus as a function of spherical aberration using adaptive optics in pseudophakic subjects. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 51, 307–313 (2025).

Kozhaya, K. et al. Effect of spherical aberration on visual acuity and depth of focus in pseudophakic eyes. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 50, (2024).

Łabuz, G., Güngör, H., Auffarth, G. U., Yildirim, T. M. & Khoramnia, R. Altering chromatic aberration: how this latest trend in intraocular-lens design affects visual quality in pseudophakic patients. Eye Vis. 10, (2023).

Haldipurkar, T. et al. Evaluation of intermediate visual outcomes in eyes implanted with bilateral advanced monofocal intraocular lens targeting for Mini-Monovision and its association with age and corneal asphericity. Clin. Ophthalmol. 18, 2929–2937 (2024).

Somani, S., Tuan, K. A. & Chernyak, D. Corneal asphericity and retinal image quality: A case study and simulations. In J. Refractive Surg. 20 (2004).

Savini, G. et al. Influence of preoperative variables on the 3-month functional outcomes of the vivity extended depth-of-focus intraocular lens: a prospective case series. Eye Vis. 12, 8 (2025).

Schmid, R. B. A. F. Optical Bench Evaluation of the Latest Refractive Enhanced Depth of Focus Intraocular Lens. ClinOphthalmol 18, 1921–1932 (2024).

Gardiner, J. C., Luo, Z. & Roman, L. A. Fixed effects, random effects and GEE: what are the differences? Stat. Med. 28, 221–239 (2009).

Funding

This study was partially funded by a grant from the Col·legi Oficial d’Òptics-Optometristes de Catalunya (COOOC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB: conception and design, data analysis, manuscript preparation, funding acquisition; EL: research execution, manuscript revision; LR: research execution, manuscript revision; CM: research execution, manuscript revision; BI: research execution, manuscript revision; IG: research execution, manuscript revision; IK: research execution, manuscript revision; MG: conception, manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be responsible for all parts of this publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr M. Guarro received grants for unrelated investigator-initiated trials from Alcon Healthcare. No other co-author declares any potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Quirón Salud Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Biarnés, M., López, E., Rodríguez, L. et al. Factors that affect distance-corrected near visual acuity in partial range of focus intraocular lenses. Sci Rep 16, 2078 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31777-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31777-6