Abstract

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a globally prevalent metabolic disorder with rising incidence. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), the most common microvascular complication in DM, disrupts autonomic nervous system regulation of cardiac and circulatory functions, thereby increasing susceptibility to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Elucidating the relationship between diabetic DPN and cardiovascular complications is critical for optimizing holistic management of diabetic patients. This study aimed to investigate the correlation between DPN and cardiovascular events in patients attending the Diabetes Clinic of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. In this cross-sectional study, 260 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), diagnosed per the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2023 criteria, were enrolled via convenience sampling. The patients with cardiovascular complications group comprised 121 patients with T2DM and documented cardiovascular events, while the control group included 138 patients with T2DM and no cardiovascular history. Data on demographic characteristics, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, clinical laboratory parameters, and neuropathy severity (assessed via the Michigan Neuropathy Screening Instrument [MNSI]) were collected. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22. The patients with cardiovascular complications had significantly higher neuropathy scores (p = 0.039), longer diabetes duration (p < 0.05), greater prevalence of hypertension (p < 0.001), and elevated serum creatinine (p = 0.020) compared to those without cardiovascular complications. In multivariable logistic regression, severe diabetic neuropathy (score > 4) was associated with increased odds of cardiovascular complications in the unadjusted model (OR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.03–2.91) and after adjustment for demographic and lifestyle factors (adjusted OR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.07–3.97; p = 0.030). A significant crude association was also observed for each one-unit increase in continuous neuropathy score (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.18; p = 0.021). A significant association was found between peripheral neuropathy and increased odds of cardiovascular disease in T2DM patients. This underscores the potential role of neuropathy as a marker for cardiovascular risk. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to explore the mechanistic interplay between neuropathy progression and cardiovascular outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DM is characterized by impaired carbohydrate and lipoprotein metabolism, along with elevated glucose levels, resulting from defects in insulin secretion or action. It is classified into two primary types: type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus1. DM is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with over 90% of diabetic patients affected by T2DM. Early identification of the disease and its complications facilitates interventions to prevent or mitigate cardiovascular diseases, which are among the principal causes of mortality in these patients2. By 2030, an estimated 532 million individuals globally are projected to have diabetes2. In China, the world’s most populous country, approximately 13% of the adult population has diabetes, with nearly half of cases remaining undiagnosed1. Given the dramatic rise in childhood obesity, concerns persist regarding a significant escalation in diabetes prevalence2. Puberty and obesity are important risk factors for T2DM, and obese children and adolescents should be carefully screened for T2DM3. Since complications of T2DM often develop years prior to clinical diagnosis, their timely recognition is critical. These complications include microvascular outcomes such as neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy, as well as macrovascular complications and severe damage to vital organs4.

A common complication of diabetes is peripheral neuropathy, whose prevalence varies based on disease duration and the severity of hyperglycemia, and is associated with substantial health and economic burdens5. Approximately 50% of diabetic patients eventually develop DPN4. The pathogenesis of DPN is highly complex, involving a combination of metabolic, vascular, and hormonal factors that disrupt the balance between nerve fiber damage and repair, favoring injury. In this process, sensory and autonomic nerve fibers are predominantly affected, leading to progressive loss of sensation and motor function, which underlies the clinical manifestations of DPN6. The symptoms and signs of DPN vary depending on the specific region of the peripheral nervous system involved7. Diabetic DPN is the most prevalent form of DPN in developed countries. Data from multiple large-scale studies indicate that nearly 50% of diabetic patients ultimately develop DPN8,9. Risk factors for DPN include the severity and duration of hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, smoking, and metabolic syndrome6.

Numerous studies have investigated the prevalence and incidence of diabetic polyneuropathy, demonstrating a positive correlation between DPN prevalence and the duration of diabetes10,11. Approximately 50% of patients with DPN are asymptomatic and may present with complications such as foot ulcers. DPN increases the odds of infection, lower limb ulcers, non-traumatic amputations, and lifelong disability, significantly impairing quality of life1. Therefore, early diagnosis of diabetic DPN is crucial for initiating timely interventions to reduce disability, prevent amputations, and improve quality of life in diabetic individuals. Concurrently, identifying risk factors for diabetes-related cardiovascular diseases plays a pivotal role in enhancing preventive strategies and the early detection of diabetic DPN12.

Hyperglycemia leads to vascular endothelial cell dysfunction. Inefficient endothelial cells promote vascular smooth muscle proliferation, inflammatory cell infiltration, and platelet aggregation, resulting in ischemia secondary to endothelial dysfunction caused by vascular constriction. These combined factors represent key events in cardiovascular diseases. DPN is associated with an elevated risk of cardiac events, and atherosclerotic diseases and cardiovascular events remain the primary cause of mortality in diabetic patients13. Notably, cardiovascular diseases are prevalent globally in the general population. In 2019, the American Heart Association reported that 48% of adults over 20 years old in the United States suffer from cardiovascular diseases, including coronary artery disease, hypertension, and heart failure14. Cardiac events account for nearly one-third to half of all cardiovascular disease cases, with ischemic heart disease being the leading cause of mortality worldwide14. Diabetic individuals are more prone to hypertension, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and elevated plasma fibrinogen levels. The risk of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients escalates with the severity of these factors15.

Several studies emphasize the critical link between diabetes and coronary heart disease (CHD), demonstrating that diabetes doubles the risk of cardiovascular diseases in men and triples it in women as they age16. In another study, among 5,163 individuals with T2DM, 9.7% died from cardiovascular diseases over a 12-year period, compared to a 2.6% cardiovascular mortality rate in 342,815 non-diabetic individuals. However, among diabetics, the addition of each risk factor markedly amplified cardiovascular events relative to non-diabetic individuals17. A study involving 229,460 participants without prior cardiovascular events found that diabetic patients faced twice the risk of coronary artery disease (CVD). The CVD risk in T2DM depends on the accumulation of risk factors and the efficacy of their management18.

DM induces progressive vascular damage and microvascular/macrovascular complications. Recent studies highlight the necessity for further research to understand the impact of patient-specific characteristics during diabetic DPN treatment19. Autonomic neuropathy, a serious complication in diabetic patients, can adversely affect heart rate and blood pressure regulation9,13,20. Given the high prevalence of diabetes in Iran and the limited studies investigating the association between DPN and cardiovascular diseases in this population, the present study aimed to determine the correlation between DPN and cardiovascular events in patients with DM. This research seeks to enhance clinical insights for managing diabetic patients and preventing disease complications.

Methods

Study type and setting

This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the association between DPN and cardiovascular complications in patients attending the Diabetes Clinic of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences in southeastern Iran. The clinic is located at Ali Ibn Abitaleb Hospital, affiliated with Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, and operates six days a week with two endocrinology subspecialists managing diabetic patients. Two trained nurses routinely measure patients’ blood pressure, height, weight, and waist circumference prior to physician consultations. All data are recorded in electronic medical files, which include patients’ medical history, longer duration of diabetes, presence of microvascular/macrovascular complications, BMI, and relevant laboratory results.

Sample size and sampling

A total of 260 eligible individuals were enrolled via convenience sampling. Diagnosis of T2DM was confirmed based on clinical history, physical examination, laboratory results, and the 2023 ADA criteria. (a) patients with cardiovascular complications group: 121 patients with T2DM and a history of cardiovascular complications (including coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction or ischemic heart disease or heart failure or coronary angioplasty or cerebrovascular diseases). History of cardiovascular complications was ascertained through a combination of patient self-report, review of medical records, and verification against documented from hospitalization records. (b) Control Group: 139 patients with T2DM but no history of cardiovascular complications. Groups were matched for age, sex, and disease duration using individual matching21.

Inclusion criteria

For both groups: age ≥ 18 years and consent to participate; in patients with cardiovascular complications group: confirmed cardiovascular complications (as defined above); in control group: absence of cardiovascular complications.

Exclusion criteria

(Applied to both groups): History of lower limb amputation, thyroid disorders, vitamin B12 deficiency, glucocorticoid use, malignancy, congenital neurological diseases, lumbar/cervical discopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, alcoholic neuropathy, or hereditary neuropathies.

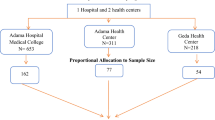

The sample size was calculated using the formula for comparing proportions between two groups, based on data from Ybarra-Muñoz et al.22. Parameters included: Z1 − α/2 = 1.96 (95% confidence level), Z1 − β = 0.84 (80% power), P1 = 30% (prevalence of DPN in diabetic patients with cardiovascular complications), P2 = 14.7% (prevalence in those without complications) and P1 − P2 = 15.3%. A target sample size of 116 participants per group was required. Accounting for anticipated incomplete questionnaires, 140 participants per group were recruited. For the final analysis, 121 patients with cardiovascular complications and 139 controls were included due to incomplete questionnaires (Fig. 1).

Data collection tools

A demographic questionnaire was used to collect information on age, sex, regular quarterly physician visits, smoking/waterpipe use, occupation, and weekly physical activity. Physical activity was categorized into three groups: (a) regular: 30-minute walks, 4–7 days/week, (b) irregular: 30-minute walks, 1–3 days/week and, (c) no physical activity: less than once/week23. Clinical data on diabetes duration, medication history, nephropathy, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, BMI, and HbA1c were extracted from medical records and laboratory tests. Weight and height were measured using a digital scale (accuracy: 0.1 kg) and stadiometer (accuracy: 0.5 cm), respectively, without shoes and in minimal clothing. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²).

Laboratory and diagnostic criteria

(a) HbA1c: Measured via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). (b) Hypertension and dyslipidemia (HDL < 40 mg/dL (men)/HDL < 50 mg/dL (women), LDL > 100 mg/dL, and triglycerides > 150 mg/dL): Diagnosed according to ADA criteria23. (c) Nephropathy: Defined as persistent albuminuria (299–300 mg/24 h or ≥ 300 mg/24 h in a 24-hour urine)23. (d) Cardiovascular disease: Confirmed by a cardiologist based on documented coronary angiography, electrocardiogram (ECG), or current coronary artery disease treatment.

Michigan neuropathy screening instrument (MNSI)

The MNSI, a validated tool for DDPN screening, was administered. This 15-item questionnaire assesses DPN symptoms through yes/no responses. Scores range from 0 to 15, with two items scored inversely (negative responses indicate neuropathy). A score > 4 indicates diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The MNSI has 80% sensitivity and 95% specificity for detecting DPN in T2DM patients and is widely used for early identification. The questionnaire was translated into Persian, and all items were culturally adapted24.

Data collection

Following the acquisition of ethical approval code from Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences and obtaining consent from the hospital director and physicians, the researcher visited the diabetes clinic. Data were obtained from patients attending the diabetes clinic from September to December 2024. The patients were initially briefed face-to-face about the research protocol, and written informed consent was obtained prior to their participation. For patients who agreed to join the study, demographic data (age, gender, occupation, regular medical visits, weekly physical activity, and tobacco/waterpipe use) were collected. Additionally, assessments for DPN (as a risk factor) were conducted using the MNSI. Clinical characteristics, including BMI, nephropathy, and CVD, were extracted from medical records and documented in a researcher-designed checklist. After necessary coordination, 3 cc of blood was collected from each patient in the morning (prior to breakfast) and sent to the laboratory for analysis of serum lipid profile, FBS, HbA1C, and creatinine levels. All collected data were subsequently entered into SPSS software (IBM® SPSS® Statistics 22) for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Qualitative variables were reported as frequency (percentage), while quantitative variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Normality of quantitative variables was assessed using skewness (− 1 to + 1) and kurtosis (− 1.96 to + 1.96), with histograms providing visual confirmation. Homogeneity of variance was evaluated via Levene’s test. (a) quantitative variables: Analyzed using the Chi-square test (if assumptions were met) or Fisher’s exact test (for small sample sizes or unmet assumptions). (b) Quantitative variables: Compared via the independent t-test (for normally distributed data) or the Mann-Whitney U test (non-parametric alternative). A binomial logistic regression model was employed to estimate the effect of CVD-related variables, calculate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), and adjust for confounders. Regression analysis followed a two-stage approach: (a) Univariate analysis: Variables with a p-value ≤ 0.25 in the bivariate analysis, along with certain variables of established clinical relevance (e.g., gender), were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. (b) Multivariate analysis: Adjusted for confounders to identify independent predictors. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). All results were reported as OR (95% CI).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, with the code of ethics No. IR.RUMS.REC.1403.011. Prior to the study’s commencement, ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. Written informed consent was acquired from all participants. All participant information remained confidential, and individuals were provided access to their data upon request. Patient data were collected solely for research purposes, and the final results were reported to all participants at the conclusion of the study. Participants retained the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

Results

This study examined the association of diabetic DPN in 260 patients. Table 1 compares demographic characteristics (gender, education level, occupation, smoking, and waterpipe use) between two groups: diabetic patients with cardiovascular events (CVD) and diabetic patients without CVD. Among the 260 participants, 32 (12.4%) had a university education. Of these, 22 individuals (68.8%) were free of CVD, suggesting that higher education levels correlate with a lower prevalence of CVD in diabetic patients (p < 0.05). Additionally, 24 out of 38 smokers (63.2%) had concurrent CVD (p < 0.05). As shown in Table 1, statistically significant associations were observed between CVD and the following variables: education level (p = 0.008), cigarette smoking (p = 0.024), and waterpipe use (p = 0.005).

Based on Table 2, only 75 patients (29.0%) out of 260 studied individuals reported engaging in regular weekly physical activity (p = 0.006). Among the 55 patients using insulin to manage their DM, 33 (60.0%) had concurrent CVD, whereas only 87 out of 204 patients (42.6%) on oral antidiabetic medications exhibited CVD events (p = 0.024). Additionally, 104 out of 175 hypertensive diabetic patients (59.4%) were diagnosed with CVD (p < 0.001).

Table 3 compares quantitative variables (neuropathy score, BMI, and duration of diabetes) between the patients with cardiovascular complications group and the control group (patients without cardiovascular events), presented as mean ± SD. The mean age of patients with cardiovascular events was 64.9 ± 9.1 years, significantly higher (p < 0.001) than the control group (56.5 ± 10.96 years). In the patients with cardiovascular complications group, the mean neuropathy score was 3.7 ± 3.5, diabetes duration was 9.3 ± 7.6 years, and BMI was 29.95 ± 5.0 kg/m². All these variables exhibited statistically significant differences between the two groups (p < 0.05). Among 121 diabetic patients with cardiovascular events, 47 (56%) had a neuropathy score > 4 (p < 0.039). The analysis revealed a significant association between higher mean neuropathy scores (≥ 3.7) and increased incidence of cardiovascular events (p < 0.032).

Table 4 examines the association between diabetic neuropathy and cardiovascular events using logistic regression models. In the univariate model, patients with a diabetic neuropathy score > 4 exhibited a 1.73-fold higher odds of cardiovascular events compared to the reference group (score ≤ 4), indicating a 73% increased odds (OR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.03–2.91, p = 0.020). When neuropathy score was analyzed as a continuous variable, each 1-unit increase in score was associated with a 9% increased odds of cardiovascular events (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.18, p = 0.021). After adjusting for age, gender, education level, smoking, waterpipe use, physical activity, BMI, and occupation (Multivariate Model 1), patients with neuropathy scores > 4 had a 2.07-fold higher odds of cardiovascular events (107% increased odds) compared to the reference group (OR: 2.07, 95% CI: 1.07–3.97, p = 0.030). However, the continuous neuropathy score showed a non-significant 10% increased odds per 1-unit increment (OR: 1.10, 95% CI: 0.99–1.21, p = 0.067).

Further adjustment for blood pressure, diabetes duration, medication type, and kidney function (Multivariate Model 2) strengthened the association: patients with neuropathy scores > 4 had a 2.17-fold higher odds of cardiovascular events (117% increased odds; OR: 2.17, 95% CI: 1.012–4.64, p = 0.046). The continuous neuropathy score remained non-significant, with an 11% increased odds per 1-unit increase (OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 0.99–1.25, p = 0.080). In logistic regression model 3, the inclusion of blood cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL, and blood sugar eliminated the association between nephropathy and cardiovascular disease, which was present in model 2.

Discussion

The present study was a case-control investigation aimed at examining the association between DPN and cardiovascular events in patients with T2DM. Our findings revealed that the prevalence of diabetic neuropathy in the study population was 32.43%. In contrast, a 10-year follow-up study by Ybarra-Muñoz et al. (2016) reported a cumulative incidence of DPN of 18.3%22. Similarly, Bjerg et al., utilizing the MNSI with a cutoff score of ≥ 4 to define DPN, documented a neuropathy prevalence of 40.7% among Danish T2DM patients25. A 2024 study by Pető et al. in Hungary identified distal sensory-motor polyneuropathy (DSPN) the earliest and most common microvascular complication of diabetes in 71.7% of participants19. These discrepancies in reported prevalence across studies highlight the influence of regional and methodological factors, warranting further exploration in future research.

A review of the literature revealed that various tools and methods have been utilized for the assessment of DPN. These instruments include the MNSI25,26, the Neuropathy Disability Score (NDS)20, the Neuropathy Symptom Score (NSS)27, the Toronto Clinical Scoring System (TCSS)21, the 10-g monofilament examination12,13, and assessment based on neurological clinical examination22. Although all these tools are valid and acceptable, caution is required in interpreting and comparing results, and due attention must be given to these differences.

A recent Hungarian study reinforced the link between DSPN and CVD19. Previous studies have confirmed that diabetic neuropathy is more prevalent in individuals with a history of myocardial infarction, and DSPN is independently associated with an elevated risk of primary cardiovascular events in T2DM27,28. Our results align with these findings. Brownrigg et al. reported that DPN correlates with increased cardiovascular risk in diabetic populations28. Pető et al. further observed higher rates of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease, and atherosclerosis in patients with DSPN (18). A 2023 UK cohort study found diabetic polyneuropathy significantly associated with both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality29. Chung et al. (2011) concluded that DSPN increases the incidence of cardiovascular events, including hypertension, in T2DM30. Similarly, a 2020 Saudi Arabian study by Ghassan Alghamdi revealed higher neuropathy rates in patients with comorbid diabetes and CVD compared to those with diabetes alone31. Karvestedt et al. demonstrated that DSPN triples the risk of cardiovascular events32, while Brownrigg et al. (2013) identified DPN as an independent risk factor for CVD in diabetes patients without prior cardiovascular history33. Kuo et al.‘s study demonstrated that DPN is a risk factor for coronary artery disease34. Independently, DPN is a predictor of primary CVD in patients with T2DM28. The association between DPN and cardiovascular events likely indicates the involvement of shared pathways, including systemic inflammation35 and lipid dysmetabolism36. The observed association between DPN and CVD likely reflects shared pathophysiological pathways, particularly low-grade chronic inflammation and autonomic neuropathy37,38. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy especially vagal withdrawal and sympathetic overactivity leads to impaired heart rate variability, endothelial dysfunction, increased vascular tone, and arrhythmogenicity, all of which contribute to heightened cardiovascular risk39,40. This neuroautonomic dysregulation, often coexisting with somatic DPN, may serve as a critical mechanistic link between peripheral nerve damage and adverse cardiac events41. Khawaja et al.‘s study found that DPN was significantly associated with dyslipidemia and cardiovascular diseases26. Although early diagnosis and appropriate intervention among high-risk groups are imperative, multiple complex factors influence the association between DPN and CVD; nevertheless, these must be taken into account by healthcare managers.

Cardiac autonomic neuropathy (CAN), characterized by dysfunction of the autonomic innervation of the heart, is a common diabetic complication. CAN disrupts heart rate regulation and vascular dynamics, contributing to acute myocardial injury and diabetic heart failure42. Our findings are consistent with this pathophysiological framework. Additionally, microvascular complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy play a critical role in diabetic heart failure, underscoring the need for cardiac screening in these patients43.

Our study further highlights the bidirectional relationship between micro- and macrovascular complications. For instance, a longitudinal study with a median 11.6-year follow-up found that individuals experiencing a macrovascular event faced twice the odds of subsequent microvascular complications44. The study by Shillah et al.45 demonstrated that a significant proportion of microvascular complications were present in a cohort of patients with T2DM. Factors such as lack of regular physical activity, obesity, hypertension, and long disease duration were significantly associated with microvascular complications45. Arnold et al.‘s study of 11,357 individuals with T2DM across 33 countries found that at enrollment, 19% had at least one microvascular complication (predominantly neuropathy) and 13.2% had at least one macrovascular complication (predominantly coronary artery disease). At the end of the 3-year follow-up period, 31.5% of patients had developed at least one microvascular complication and 16.6% had developed at least one macrovascular complication46. These results emphasize the importance of early identification and management of both micro- and macrovascular complications to mitigate cardiovascular morbidity in diabetes.

The mean age of patients with cardiovascular events was 64.9 years, with a neuropathy score of 3.7 and a diabetes duration of 9.3 years. Salinero-Fort et al. identified age ≥ 75 years as a cardiovascular risk factor in diabetic patients47. Pető et al. similarly demonstrated that advanced age and cardiovascular complications may increase the risk of DSPN19. Existing literature highlights age as an independent risk factor for DSPN progression in T2D, likely due to vascular aging, endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, and cumulative axonal damage over time48,49. A meta-analysis further confirmed age as an independent risk factor for DPN in T2D50. In our study, cardiovascular odds appeared to increase with diabetes duration. Contrary to these findings, Pető et al. reported no association between diabetes duration and cardiovascular complications19. This discrepancy may stem from the fact that both groups in Pető et al.’s cohort had long-term diabetes19. Routine screening for diabetic neuropathy may facilitate early detection of peripheral nerve dysfunction in diabetic patients. Emphasizing glycemic control, enhanced monitoring of microvascular complications, and integrating neuropathy screening into diabetes care protocols may improve the identification and mitigation of cardiovascular risks in T2D populations.

Limitations

The strengths of this study include data collection from a sufficiently large sample of Iranian patients with T2DM, confirmed through validated instrumental examinations, which enabled a comprehensive assessment of risk factors, cardiovascular diseases, and microvascular complications. However, interpreting these findings requires careful consideration of several limitations. This study was a single-center study with a small sample size. Second, the study population was ethnically Iranian, limiting the generalizability of results to other ethnic groups. Also, due to unmatched age and gender, residual confounding may be present. Additionally, due to patients’ ongoing pharmacological treatments, such as lipid-lowering drugs, we could not fully control for the effects of triglycerides and other clinical laboratory parameters. For future studies, we recommend enrolling pre-diabetic individuals not on medication and also on lipid-lowering drugs to evaluate better the effects of lipid profiles, FBS, HbA1C, and other laboratory parameters. Prospective studies should also focus on diabetic patients without a history of cardiovascular events and neuropathy scores less than 4 to examine the association between these variables. Monofilament testing was not used in the present study. Therefore, for a more accurate assessment of peripheral neuropathy in future studies, it is recommended to use standard tools such as the 10-gram monofilament and dermatome sensory testing. These methods provide more precise information about neuropathic status. Cardiovascular disease confirmation relied on cardiac records (e.g., ECG, angiography). We therefore propose the use of more sensitive tests (e.g., stress testing, echocardiography) in future studies. In the present study, the MNSI cutoff point is set at 4; however, some studies have adopted lower cutoff values, which should be further investigated in future research. Our definition of cardiovascular disease encompassed a composite endpoint including coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease. While this approach enhances statistical power by capturing clinically relevant endpoints, it may mask differential associations between specific CVD subtypes and DPN. Future prospective studies with subtype-specific analyses are warranted.

Conclusion

This study provides preliminary insights into the prevalence of DPN and its association with cardiovascular events in southeastern Iran. Our central finding is that patients with cardiovascular events exhibited significantly higher neuropathy scores, confirming a significant correlation between DPN and cardiovascular disease in T2DM patients. Although other comorbid factors were observed at higher rates in the affected group, the strong association with neuropathy highlights its potential importance as a key indicator or risk factor. Further prospective studies are essential to validate this correlation and to unravel the pathophysiological mechanisms linking DPN to cardiovascular outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, Q. et al. Predicting the risk of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese elderly using machine learning techniques. J. Personalized Med. 12 (6), 905 (2022).

Saeedi, P. et al. Mortality attributable to diabetes in 20–79 years old adults, 2019 estimates: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 162, p108086 (2020).

Dündar, İ. & Akıncı, A. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and related morbidities in overweight and obese children. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 35 (4), 435–441 (2022).

Davies, J. L. et al. Composite nerve conduction scores and signs for diagnosis and somatic staging of diabetic polyneuropathy: mid North American Ethnic Cohort Survey. Muscle Nerve 1, 1 (2023).

Shillo, P. et al. Painful and painless diabetic neuropathies: what is the difference? Curr. Diab. Rep. 19, 1–13 (2019).

Feldman, E. L. et al. New horizons in diabetic neuropathy: mechanisms, bioenergetics, and pain. Neuron 93 (6), 1296–1313 (2017).

Thaisetthawatkul, P. & Dyck, P. J. B. Asymmetric diabetic neuropathy: radiculoplexus neuropathies, mononeuropathies, and cranial neuropathies. In Diabetic Neuropathy: Advances in Pathophysiology and Clinical Management 165–181 (Springer, 2023).

Bondar, A. et al. Diabetic neuropathy: A narrative review of risk factors, classification, screening and current pathogenic treatment options. Experimental Therapeutic Med. 22 (1), 1–9 (2021).

Røikjer, J. & Ejskjaer, N. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy: diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Drug Saf. 16 (1), 2–16 (2021).

Pirart, J. Diabetes mellitus and its degenerative complications: a prospective study of 4,400 patients observed between 1947 and 1973. Diabetes Care. 1 (4), 252–263 (1978).

Chukwubuzo, O. T. et al. Prevalence and associations of neuropathic pain among subjects with diabetes mellitus in the Enugu diabetic peripheral neuropathy (Edipen) study. J. Pharm. Negat. Results. 1, 10104–10117 (2022).

Elbarsha, A., Hamedh, M. & Elsaeiti, M. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ibnosina J. Med. Biomedical Sci. 11 (01), 25–28 (2019).

Quiroz-Aldave, J. et al. Diabetic neuropathy: Past, present, and future. Caspian J. Intern. Med. 14 (2), 153 (2023).

Dunlay, S. M. et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure, a scientific statement from the American heart association and heart failure society of America. J. Card. Fail. 25 (8), 584–619 (2019).

Jyotsna, F. et al. Exploring the complex connection between diabetes and cardiovascular disease: analyzing approaches to mitigate cardiovascular risk in patients with diabetes. Cureus 15 (8), 1 (2023).

Marx, N. et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes: developed by the task force on the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 44 (39), 4043–4140 (2023).

Rawshani, A. et al. Risk factors, mortality, and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 379 (7), 633–644 (2018).

Dludla, P. V. et al. Pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: implications of inflammation and oxidative stress. World J. Diabetes. 14 (3), 130 (2023).

Pető, A. et al. Correlations between distal sensorimotor polyneuropathy and cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients in the North-Eastern region of Hungary. PLoS ONE. 19 (7), e0306482 (2024).

Baltzis, D. et al. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy as a predictor of asymptomatic myocardial ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Adv. Therapy. 33, 1840–1847 (2016).

Li, L. et al. Impaired vascular endothelial function is associated with peripheral neuropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome Obesity: Targets Therapy. 1, 1437–1449 (2022).

Ybarra-Muñoz, J. et al. Cardiovascular disease predicts diabetic peripheral polyneuropathy in subjects with type 2 diabetes: A 10-year prospective study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 15 (4), 248–254 (2016).

ElSayed, N. A. et al. Introduction and methodology: standards of care in diabetes—2023. Am. Diabetes Assoc. 1, S1–S4 (2023).

Viswanathan, V. et al. Precision of Michigan neuropathy screening instrument (MNSI) tool for the diagnosis of diabetic peripheral neuropathy among people with type 2 diabetes—a study from South India. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 15347346231163209 (2023).

Bjerg, L. et al. Diabetic polyneuropathy early in type 2 diabetes is associated with higher incidence rate of cardiovascular disease: results from two Danish cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 44 (7), 1714–1721 (2021).

Khawaja, N. et al. The prevalence and risk factors of peripheral neuropathy among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus; the case of Jordan. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 10, 8 (2018).

Wang, W. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a population-based cross‐sectional study in China. Diab./Metab. Res. Rev. 39 (8), e3702 (2023).

Brownrigg, J. R. et al. Peripheral neuropathy and the risk of cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Heart 100 (23), 1837–1843 (2014).

Kim, K. et al. Associations of polyneuropathy with risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular disease events stratified by diabetes status. J. Diabetes Invest. 14 (11), 1279–1288 (2023).

Chung, J. O. et al. Association between diabetic polyneuropathy and cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Metabolism J. 35 (4), 390 (2011).

AlGhamdi, G. et al. Peripheral neuropathy as a risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease in diabetic patients. Cureus 12 (12), 1 (2020).

Karvestedt, L. et al. Peripheral sensory neuropathy associates with micro-or macroangiopathy: results from a population-based study of type 2 diabetic patients in Sweden. Diabetes Care. 32 (2), 317–322 (2009).

Brownrigg, J. et al. Peripheral neuropathy is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events among individuals with diabetes mellitus. Am. Heart Assoc. 1, 1 (2013).

Kuo, C. S. et al. Residual risk of cardiovascular complications in statin-using patients with type 2 diabetes: the Taiwan diabetes registry study. Lipids Health Dis. 23 (1), 24 (2024).

Kellogg, A. P. et al. Protective effects of cyclooxygenase-2 gene inactivation against peripheral nerve dysfunction and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss in experimental diabetes. Diabetes 56 (12), 2997–3005 (2007).

Rumora, A. E. et al. Plasma lipid metabolites associate with diabetic polyneuropathy in a cohort with type 2 diabetes. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 8 (6), 1292–1307 (2021).

Bakkar, N. M. Z. et al. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy: a progressive consequence of chronic low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes and related metabolic disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (23), 9005 (2020).

Yunir, E. et al. Factors affecting mortality of critical limb ischemia 1 year after endovascular revascularization in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 18 (1), 20 (2022).

Vinik, A. I., Erbas, T. & Casellini, C. M. Diabetic cardiac autonomic neuropathy, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J. Diabetes Invest. 4 (1), 4–18 (2013).

Pop-Busui, R. Autonomic diabetic neuropathies: a brief overview. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 206, 110762 (2023).

Sudo, S. Z. et al. Diabetes-induced cardiac autonomic neuropathy: impact on heart function and prognosis. Biomedicines 10 (12), 3258 (2022).

Vinik, A. I. et al. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: a predictor of cardiometabolic events. Front. NeuroSci. 12, 591 (2018).

Mordi, I. R. et al. Microvascular disease and heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction in type 2 diabetes. ESC Heart Fail. 7 (3), 1168–1177 (2020).

Polemiti, E. Identifying Risk of Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes: Findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam Study (Universität Potsdam, 2022).

Shillah, W. B. et al. Predictors of microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at regional referral hospitals in the central zone, tanzania: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 5035 (2024).

Arnold, S. V. et al. Incidence rates and predictors of microvascular and macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes: results from the longitudinal global discover study. Am. Heart J. 243, 232–239 (2022).

Salinero-Fort, M. A. et al. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with acute myocardial infarction and stroke in the MADIABETES cohort. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 15245 (2021).

Unnikrishnan, R. et al. Younger-onset versus older-onset type 2 diabetes: clinical profile and complications. J. Diabetes Complicat. 31 (6), 971–975 (2017).

Nanayakkara, N. et al. Age, age at diagnosis and diabetes duration are all associated with vascular complications in type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 32 (3), 279–290 (2018).

Nanayakkara, N. et al. Impact of age at type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis on mortality and vascular complications: systematic review and meta-analyses. Diabetologia 64, 275–287 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would thank the authorities of the Clinical Research Development Unit, Ali-Ibn Abi-Talib Hospital, Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan, Iran. Researchers also thank all the students who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP, ZK, MS, PK and MK conceptualized, designed, analyzed, and interpreted the data, prepared a draft manuscript and edited the manuscript. MAZ, AHH, SKH and IJ conceptualized and edited the manuscript. MK, MP and MAZ contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, with the code of ethics No. IR.RUMS.REC.1403.011. All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participating in this study. All participants agreed to be included in the study anonymously.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Poorrezaei, M., Zakeri, M.A., Kamiab, Z. et al. Associations between peripheral neuropathy and cardiovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 16, 2129 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31797-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31797-2