Abstract

Medulloblastoma (MB) is the most common malignant pediatric brain tumor and shows marked molecular and clinical heterogeneity. Molecular subgrouping guides prognosis and treatment but remains scarce in low- and middle-income countries. We analyzed 84 pediatric MB cases from Argentina using a cost-effective, integrative workflow combining low- and high-complexity techniques. Tumors were classified following 2021 WHO guidelines, assessing links between molecular groups, risk, histology, location, and overall survival (OS). Non-WNT/non-SHH tumors predominated (60.7%), followed by SHH-activated (27.4%) and WNT-activated (10.7%). SHH TP53 − tumors were more common in infants, while WNT tumors occurred only in older children/adolescents. Group-specific alterations included CTNNB1 and chromosome 6 changes in WNT tumors, and MYCN and i17q in non-WNT/non-SHH tumors. SHH TP53 + tumors correlated with very high biological risk and poor OS, whereas WNT tumors had favorable outcomes. Low-cost methods resolved 90% of cases; NanoString clarified the remainder, achieving 98.8% precision. This first molecular characterization of pediatric MB in Argentina demonstrates that a tiered, conventional-tools-based approach can deliver high diagnostic accuracy and prognostic value, supporting its integration into routine care in resource-limited settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medulloblastoma (MB), a malignant embryonic tumor of the cerebellum, constitutes the most common pediatric brain malignancy, accounting for about 20% of all childhood brain tumors worldwide1. In Argentina, MB accounts for 17% of central nervous system (CNS) tumors in children under 15 years of age and shows a 5 year overall survival (OS) of about 52%2.

The aggressive nature of MB and its considerable heterogeneity give rise to the necessity for a multidisciplinary approach in understanding its histological and molecular complexity for effective management and prognosis, and is also of paramount importance for tailored therapeutic interventions3.

From an anatomical perspective, medulloblastoma arises from the cerebellar vermis or hemisphere, frequently infiltrating into the fourth ventricle, and were historically classified into four histological subtypes: (i) classic (CL), (ii) desmoplastic/nodular (DN), (iii) medulloblastoma extensive nodularity (MBEN) and (iv) large cell/anaplastic (LC/A)4. However, during the last decades, molecular insights have revolutionized classification, delineating distinct groups with varying clinical behaviors and treatment responses. The 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous system recognizes four main molecular groups: (i) WNT-activated, (ii) SHH-activated and TP53-wildtype (SHH TP53-), (iii) SHH-activated and TP53-mutant (SHH TP53+), and (iv) non-WNT/non-SHH group, which includes Group 3 (G3) and Group 4 (G4) MB3. Moreover, by assessing the tumor transcriptome and large scale methylation profiling, these initial molecular groups have been further sub-classified into multiple WNT subgroups, four SHH subgroups, and eight non-WNT/non-SHH subgroups, each with unique genetic aberrations and clinical features5. Commonly, WNT-activated tumors are characterized by activation mutations in the WNT signaling pathway, present classic morphology and exhibit favorable outcomes3,6. Additionally, the WNT group often harbors single nucleotide variants (SNV) in TP53, DDX3 and CTNNB1 genes; the latter causing β-catenin immunoreactivity in tumor cell nuclei, while MB in other molecular groups may show cytoplasmic expression of β-catenin3,7. Meanwhile, SHH-activated tumors are driven by aberrations in the sonic hedgehog signaling pathway and a majority of cases show desmoplastic/nodular or extensive nodularity morphology; however, a minority may display large cell/anaplastic morphology. This morphology-heterogeneity ultimately results in a more varied OS rate within SHH-activated MB. Moreover, the presence of a genetic alteration in TP53 gene further worsens the OS of SHH TP53 + tumors1,8. Despite the primary importance of TP53 gene variants in the SHH group classification, copy number variations (CNV) and SNVs in other genes were described in other molecular groups (extensively reviewed in9). In this regard, the main difference could be that while both tumor types, SHH-activated and WNT-activated MB, may express YAP1 protein, SHH-activated MB do not show nuclear immunoreactivity for β-catenin3,9. On the contrary, G3 and G4 tumors lack a distinctive signaling pathway alteration, but commonly present genomic instability, reflected by the presence of isochromosome 17q (i17q), which affects the expression of proto-oncogenes GFI1 and GFI1B. Additionally, G3 MB may harbor sequence variations in SMARCA4, KDM genes, and OTX2 genes, while sequence variation in MYCN and CDK6 genes and overexpression of PRDM6 were also described for G4 MB1. Regarding disease progression G3 and G4 tumors manifest a more aggressive behavior, necessitating intensified therapeutic approaches1.

The overall heterogeneity displayed by MB suggests that accurate molecular grouping is not only necessary to define risk stratification, but also may assist in personalized therapeutic interventions, emphasizing the importance of precision medicine in MB management5. In this context, tailored treatments based on molecular groups may enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects, a critical consideration in a developing child. For instance, WNT-activated tumors may benefit from reduced chemotherapy regimens owing to their favorable prognosis, whereas G3 tumors might necessitate intensified treatments to improve outcomes. Similarly, targeted therapies directed against a specific molecular aberration may increase treatment response and mitigate tumor resistance9.

Since MB represents a paradigmatic example of tumors where histological and molecular classifications delineate distinct groups with varying clinical behaviors and prognosis, we sought to assess the presence of molecular alterations in a pediatric series of MB cases from Argentina and correlate these findings with clinical prognosis and survival outcomes. With this study we aim to contribute to the growing body of knowledge that supports personalized treatment approaches, ultimately enhancing the survival and quality of life for affected children.

Results

Considering that medulloblastoma management is multidisciplinary and depends on patients´ age and molecular characteristics we evaluated a series of 84 pediatric patients with a cost-effective, robust and feasible-to-implement strategy for molecular classification in routine practice, with a particular focus on applicability in resource-constrained countries. The cohort’s median age at time of diagnosis was 5 years (range: 0.1–16 years) and 49/84 (58.3%) were males. The most frequent anatomical localization was the midline/fourth ventricle with 62/84 (73.8%) cases. Regarding histological classification, large-cell/anaplastic was the predominant histological subtype in 37/84 (44.1%) cases, followed by the classic subtype in 33/84 (39.3%) cases. Considering age, tumor resection and metastasis, clinical risk was defined as standard for 28/84 (33.3%) cases and as high-risk in 56/84 (66.7%) cases (Table 1).

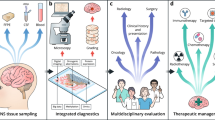

In parallel, the molecular classification was assessed by conventional techniques, namely IHC, FISH and direct Sanger sequencing complemented by a high-throughput technique such as NanoString nCounter assay for MB grouping (Fig. 1). No full-concordance between the approaches for molecular classification was observed in 7 cases where the NanoString assay was considered conclusive. On the other hand, NanoString assay could not reach a definitive classification in 16 cases, either because of poor quality of purified RNA (6 cases) or because of the lack of significant clustering given by RNA expression of the sampled genes (10 cases); all of them resolved by conventional techniques. Definitive molecular classification was reached after combining both approaches and in this way, non-WNT/non-SHH group was the most prevalent, in 51/84 (60.7%) cases, and these were further sub classified into G3 subgroup [14/51 (27.4%)], G4 subgroup [19/51 (37.3%)] and G3/G4 subgroup [18/51 (35.3%)].

Heat map clustering of MB cases (n = 58). On the top and on the right side, each color bar represents a medulloblastoma molecular group: SHH-activated (red), WNT-activated (blue), Group 3 (yellow) and Group 4 (green). Gene expression score scale goes from dark blue (− 1) to dark red (+ 1), with red: increased gene expression, blue: decreased gene expression and white: no differential expression. Inconclusive and not classifiable cases were not included in the heat map.

When comparing the distribution of molecular groups across ages, SHH TP53- tumors were more prevalent within infants (< 3 years) but absent in the adolescents group (14 to < 19 years). On the other hand, WNT-activated tumors occurred among children (3 to < 14 years) and adolescents, but absent among infants. Meanwhile, the non-WNT/non-SHH group was the most prevalent and present in all the three ages (Fig. 2A; Table 1).

Distribution of molecular groups of pediatric medulloblastoma. (A) Bar graph representing MB molecular groups in relation to age groups. (B) Pie chart showing the distribution of MB molecular groups among histological subtypes. (C) Pie chart representing distribution of MB molecular groups related to anatomic location of the tumor. (D) Bar graph depicting the distribution of MB molecular groups according to metastasis occurrence. M0: absence of metastasis; M1: presence of metastasis.

Regarding the associations among histological subtypes and molecular classifications, only the SHH-activated group, regardless of TP53 status, showed an association with DN (Fisher exact test, P = 0.0001) and MBEN (Fisher exact test, P = 0.005) subtypes; however, associations were lost when considering TP53 status. Moreover, from the 10 SHH-activated and DN cases, 9 happened in infants (Fisher exact test, P = 0.041). Interestingly, of the 4 MBEN cases, 2 of them occurred in the infant group. On the other hand, the WNT-activated tumors never contained the DN or MBEN histological subtypes and the non-WNT/non-SHH group contained LC/A or CL subtypes, (Table 1; Fig. 2B).

Concerning anatomical location, the cerebellar hemisphere mainly harbored SHH-activated tumors 7/9 (77.7%), and of theses, 6/7 (85.7%) were SHH TP53- tumors (Chi-square test of independence, P = 0.0012; standardized residual (SR) for cerebellar hemispheres and SHH TP53- = 3.87) (Table 1; Fig. 2C). Among those 19 patients who presented with metastasis, 12 cases were classified as non-WNT/non-SHH tumors (63.15%) (Table 1; Fig. 2D); however, the occurrence of metastasis was not favored in any given molecular group.

The most prevalent genetic alterations in our series concerned YAP1 overexpression and TP53 gene, the latter detected either by its overexpression by IHC or by SNVs as evaluated by Sanger sequencing in 24/84 (28.5%) cases each, followed by GAB1 overexpression in 19/84 cases (22.6% and Table 2).

Regarding the association between molecular groups and genetic alterations, TP53 mutant tumors were distributed mostly in the non-WNT/non-SHH group (12/24 cases) and 10/24 in the SHH TP53 + group (Table 2). Additionally, alterations in CTNNB1 gene and chromosome 6 monosomy exclusively occurred among the WNT-activated tumors. Specifically, nuclear β-catenin immunoreactivity was observed exclusively in 4 cases of the WNT-activated group, all of which harbored a SNV in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene as assessed by Sanger sequencing. On the other hand, negative cases for β-catenin immunoreactivity, whether from other molecular subgroups or within the WNT-activated group, mainly showed cytoplasmic β-catenin expression and no SNVs in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene. On the other hand, 15/18 (83.3%) MB that evidenced MYCN amplification and 7/8 (87.5%) that displayed MYC amplification were of the non-WNT/non-SHH molecular group. Finally, GAB1 and YAP1 altered tumors were predominant in the SHH-activated group and the occurrence of i17q was exclusively present in the non-WNT/non-SHH group (Table 2). The Chi-square test of independence disclosed a highly significant statistical association between molecular groups and genetic alterations (χ²-test of independence, P = 6.72 × 10− 17). Further analysis of SR confirmed that CTNNB1 and chromosome 6 monosomy were significantly associated with WNT-activated tumors (SR = 4.38 for CTNNB1 and 4.90 for chromosome 6 monosomy) (Fig. 3A). In turn, GAB1 and YAP1 overexpression were significantly associated with SHH TP53- tumors (SR = 2.86 and SR = 3.16, respectively). Finally, i17q occurrence and MYCN amplification were significantly associated with non-WNT/non-SHH group (SR = 2.85 and SR = 2.58, respectively). Surprisingly, alterations of MYC resulted borderline not associated with this same molecular group (SR = 1.90) (Fig. 3A). However, when considering G3 and G4 MB subgroups separately, MYCN amplifications were detected in 7/19 (36.8%) G4 MB and MYC amplification was detected in 4/14 (28.5%) G3 MB, although neither disclosed a significant association.

(A) Heat map plotting the standardized residuals following the Chi-square test of independence relating the genetic alterations and molecular groups. Standardized residuals greater than + 2 or less than − 2 (>|2|) were considered statistically significant. (B) Heat map plotting the standardized residuals following the Chi-square test of independence relating the biological risk and molecular groups. Standardized residuals greater than + 2 or less than − 2 (>|2|) were considered statistically significant. Undetermined Biological risk cases were excluded from the analysis. For the Kaplan-Meier overall survival analysis, 62 cases were considered. (C) Kaplan-Meyer overall survival analysis related to molecular groups; P values for each molecular group as compared to WNT-activated MB. Molecular subgroups cases as follows: WNT-activated (n = 7), SHH TP53– (n = 6), SHH TP53+ (n = 6), and non-WNT/non-SHH (n = 43). (D) Kaplan-Meyer overall survival analysis related to anatomical locations; P values for each anatomic location as compared to Vermis / Brain Stem. Cases were distributed among anatomical location as follows: Vermis / Brain Stem (n = 11), Midline / IV Ventricle (n = 46), and Hemispheres (n = 5). (E) Kaplan-Meyer overall survival analysis related to TP53 status (18 cases were TP53 + and 44 cases were TP53-).

Biological risk was assessed whenever possible: 8 cases were determined as low risk, 19 as standard risk, 14 as high risk and 16 as very high risk; the remaining 27 cases were classified as undetermined (Table 1). Excluding all undetermined biological risk cases, most WNT-activated tumors 6/8 (75%) presented with a low biological risk, whereas the SHH TP53- tumors 9/12 (75%) presented with a standard biological risk and SHH TP53 + tumors, 10/10 (100%), with a very high biological risk. Hence, a statistically significant association between the molecular groups and the biological risk stratification was disclosed (χ²-test of independence, P = 1.71 × 10− 10) (Table 1). Further analysis of standardized residuals revealed that WNT-activated tumors were significantly associated with low biological risk (SR = + 4.54), while SHH TP53 + tumors showed a strong association with very high risk (SR = + 4.23) (Fig. 3B). Additionally, SHH TP53- tumors were overrepresented in the standard-risk category (SR = + 2.44). These findings reinforce the value of molecular classification in the prognostic stratification of pediatric MB patients.

Overall survival was assessed in a subset of 62 patients, 37 died and 25 achieved the 5 years of follow-up. The OS significantly differed based on the molecular groups, where the WNT-activated tumors presented a higher OS as compared to SHH TP53 + tumors (Kaplan-Meyer, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test, P = 0.026) and the non-WNT/non-SHH group (Kaplan-Meyer, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test, P = 0.038) (Fig. 3C). In a similar way, OS also differed significantly based on the anatomical location, where tumors arising in the cerebellar vermis/brain stem presented the highest OS as compared to those arising in the cerebellar hemispheres or in the midline/IV ventricle (Kaplan-Meyer, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test, P = 0.024 and P = 0.034, respectively) (Fig. 3D). Overall survival did not vary regarding histological subtypes, clinical or biological risk. Among the specific molecular changes, only the presence of a TP53 alteration was associated with a significant decrease in OS (Kaplan-Meyer, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test, P = 0.022) (Fig. 3E).

Discussion

This study offers a comprehensive molecular and clinicopathologic characterization of pediatric MB in Argentina, utilizing a combination of immunohistochemistry, fluorescence in-situ hybridization, Sanger sequencing and NanoString-based classification. Our approach, designed to be cost-effective and feasible in low-to-middle-income countries, enabled accurate molecular subgrouping and highlighted key associations between molecular alterations, clinical features and patient outcomes.

The non-WNT/non-SHH MB, which encompass Group 3 and Group 4, was the most prevalent in our cohort (60.7%); notably, WNT-activated tumors, associated with favorable outcomes, comprised the smaller fraction (approximately 10%), while SHH-activated tumors represented around 27%. All of these were in line with most previous reports from other geographic regions1,5,6,10,11. On the other hand, LC/A was the most frequent histologic subtype in our series, which contrast with most published reports where CL histologic subtype is the most prevalent worldwide3,12. However, LC/A is one of the most frequent histologic subtype in the non-WNT/non-SHH molecular group13,14, a fact that could bias our observations regarding histologic subtypes frequencies. Additionally, demographic biases have also been described as molecular classification progresses in the modern era13.

Furthermore, age-related molecular-group patterns were evident: SHH-activated tumors prevailed among infants, followed by non-WNT/non-SHH tumors; however, this pattern shifted in children, while WNT-activated tumors occurred mainly in adolescents. Similar age-related patterns were observed in children from different geographies15, a fact that suggests an association with ontogeny and/or developmental stage rather than with the genetic background. Age bias should also be taken into consideration when defining age groups in the design of clinical trials.

Histological and molecular associations, as described in our cohort, further validated the current observations for other geographical regions13,14. Of note, SHH-activated tumors were significantly associated with DN and MBEN histology, particularly among infants. However, these associations were attenuated when stratifying by TP53 status, suggesting additional modifying factors. Conversely, WNT tumors consistently exhibited CL histology and lacked DN or MBEN features. The non-WNT/non-SHH group exhibited LC/A or CL subtypes, in line with their recognized histopathological heterogeneity.

Interestingly, in our cohort, tumors arising in the cerebellar vermis/brain stem showed an increased OS, something that was also reported in children from Thailand16; however, Rutkowski et al., reported an increased OS in tumors of the cerebellar hemisphere17. Given the scares and contradictory data available on OS and anatomical location in MB, future studies addressing this gap are both expected and necessary. Recent studies integrating molecular and single-cell transcriptomic data have provided a clearer picture of the developmental origins of medulloblastoma molecular groups. WNT-activated tumors are now thought to derive from mossy fiber neuron progenitors of the dorsal brainstem, while SHH-activated tumors originate from granule neuron progenitors within the external granular layer of the cerebellum. In turn, Group 3 and Group 4 tumors appear to arise from progenitor cells of the rhombic lip and unipolar brush cell lineages, respectively18,19. These distinct neurodevelopmental origins likely contribute to the differences in tumor localization; however, further mechanistic studies are necessary to establish a link between the putative cells of origin and the observed overall survival among the molecular groups.

The identification of specific genetic variation provided additional insights; alterations in TP53, found in 28.6% of cases, mainly occurred in SHH TP53 + and non-WNT/non-SHH groups, highlighting its role in high-risk disease, as further confirmed by the observed decreased OS of tumors harboring TP53 alterations and the decreased OS of SHH TP53 + and non-WNT/non-SHH as compared with WNT-activated tumors. Similarly, previous reports demonstrated that alterations in TP53 in WNT-activated tumors did not correlate with a poorer outcome1,20, meaning that an altered TP53 gene is not sufficient to worsen WNT-activated tumors prognosis13,21. This latter observation could only be partially ratified in our study, since only 1 child in this latter category survived the 5 year follow-up, but another one is still under follow-up (26 months). Disparities between WNT- and SHH-activated MB may stem from their distinct developmental origins, as well as the possibility that TP53 mutations may have varying effects depending on the specific cell type involved20. Moreover, the fact that a subset of SHH-activated MB contain germline mutations in TP53 and that WNT-activated MB may harbor TP53 somatic mutations could also account for this prognosis difference13,21. Overall and even though TP53 has been extensively described as a negative factor contributing to an adverse outcome8,21, its role in WNT-activated MB is not yet fully understood.

As expected, in line with previous reports from other geographies1,7,20, alterations in CTNNB1 gene and chromosome 6 monosomy only occurred in the WNT-activated tumors, confirming its usefulness as a diagnostic factor. However, these two biomarkers by themselves would fail to classify up to about 15% of WNT-activated MB, which could represent a diagnostic limitation13 and strengthens the need for additional germline molecular markers6.

Concerning MYC gene family, MYC amplification occurred in G3 cases with a rather higher frequency (28.5%) than previously reported (17–20%) 1,7,13,20; however, MYC amplification was not limited to G3 MB, as it was also present in G4 cases. Meanwhile, and also in line with these previous reports, MYCN amplifications preferentially occurred in G4 MB, but were not restricted to this group, since 1/14 (7%) G3 MB also presented MYCN amplification.

In concordance with Cho et al., biological risk classification, when available, aligned well with molecular subgroups: WNT tumors were generally low risk, SHH TP53- tumors were standard risk, and SHH TP53 + tumors were universally very high risk22. Although not all cases could be assigned a biological risk, the correlations depicted in this study support the notion of integrating molecular data into risk stratification schemas. Furthermore, as previously described in several reports, survival analysis confirmed the prognostic utility of molecular subgrouping13,14; WNT tumors had the best overall survival, while SHH TP53 + and non-WNT/non-SHH groups had significantly poorer outcomes. Anatomical location also emerged as a prognostic factor, with tumors arising in the cerebellar vermis associated with better survival than those in the hemispheres. Histology, clinical risk, and biological risk did not show statistically significant differences in survival, further emphasizing the dominant role of molecular features.

The classification pipeline we employed, combining conventional and high-throughput techniques, proved effective and reproducible. While some discrepancies were noted in a minority of cases lacking full concordance, the NanoString assay was instrumental in resolving classification ambiguities. While IHC cannot differentiate between Groups 3 and 4, FISH does not account for single nucleotide variants, Sanger sequencing cannot detect large rearrangements and good quality RNA for NanoString assay is difficult to obtain from older archived FFPE, and it is not available at most centers, all these methods complement each other and can be used in combination for high confidence classification of molecular groups in clinical practice.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design, based on sample availability, potential selection bias, and the incomplete assignment of biological risk in a subset of cases. Additionally, while our molecular profiling approach was comprehensive and accounted for the most frequent genetic alterations in pediatric MB, it did not include DNA methylation profiling, which is increasingly recognized as a standard for precise MB sub-classification.

In conclusion, our pipeline resolved 90% (76/84) of molecular classifications using low-cost techniques alone, with NanoString serving to clarify ambiguous cases reaching 98.8% (83/84 cases) precision diagnosis. The study provides critical insights into the molecular landscape of pediatric MB in Argentina and demonstrates that a tiered approach using conventional molecular tools can achieve high diagnostic accuracy, enabling meaningful group stratification and prognostic prediction even in resource-constrained settings. These findings confirm the feasibility and clinical utility of integrated molecular diagnostics, and reinforce the importance of supporting their integration into routine medulloblastoma management across diverse healthcare systems. Future research should prioritize the expansion of molecular analyses, including methylation profiling, and the validation of findings in larger, prospective cohorts to further refine therapeutic strategies and improve outcomes for children with medulloblastoma.

Methods

Ethics approval

Hospital’s ethics committee, Comité de Ética en Investigación, has reviewed and approved this study (CEI N° 20.59), which is in accordance with the human experimentation guidelines of our institution and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Data were last accessed for research purposes on April 1st 2025; and in accordance with the Argentinean Habeas Data Law Nº 25.326, authors had no access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection. A written informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or patients guardians.

Patients and samples

Eighty-four pediatric patients diagnosed with medulloblastoma who had undergone surgery, received treatment and follow-up at Hospital de Niños "Dr. Ricardo Gutiérrez" (HNRG) between 2013 and 2023 or at Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (HIBA) between 2005 and 2023 were included in the study. Inclusion criteria were: (i) a confirmed medulloblastoma diagnosis, (ii) under 19 years of age, (iii) had signed a written informed consent, and (iv) sufficient biopsy material left after routine histological diagnosis. A gross total resection was performed whenever possible, while a partial tumor resection was performed due to inaccessible anatomical location or when the tumor infiltrated sensitive anatomic structures. In the latter cases, the remaining tumor masses were either < 1.5 or > 1.5 cm2; these parameters, together with the patients’ age and metastasis occurrence, were used to define clinical risk23. The tumor resection was formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE). Histological sections were evaluated by two independent pathologists (SLC and SBC) and after histological and molecular analyses; cases were classified according to the most recent WHO 2021 classification of tumors of the central nervous system guidelines3.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Four micrometer thick FFPE tissue slides were tested with antibodies anti-YAP1 (clone Sc-101199, Santa Cruz, USA), anti-Beta-catenin (clone 14, Bio SB, USA), anti-p53 (clone DO7, Bio SB, USA) and anti-GAB1 (clone 06-579, Millipore - Merck, USA) in a BenchMark Ultra automated stainer device (Ventana-Roche, Switzerland) as described in24.

P53 expression was quantified as the number of positive nuclei divided by the total number of nuclei ×100, in four representative areas of the tumor at 400× magnification and cases with nuclear P53 staining, either strong or weak, in ≥ 10% of tumor cells were classified as positive. Tumor cells with nuclear β-catenin staining in ≥ 10% of tumor cells were classified as positive; while cytoplasmic staining or nuclear labeling in < 10% of tumor cells were considered as negative. Cases showing cytoplasmic staining of tumor cells for GAB1 or YAP1 were considered positive, without applying a cut-off value. For each immunohistochemistry assay (P53, β-catenin, GAB1, and YAP1), three additional MDB tissue sections were included: a previously characterized positive case and a negative case, as well as a no-primary antibody slide. In addition, the absence of staining in tissue components expected to remain unlabeled, such as the vascular endothelium, was used as an internal negative control for each biopsy. The immunohistochemical interpretation of all cases was independently performed by two pathologists (SLC and SBC). Prior to the review, both pathologists agreed upon the evaluation criteria to be applied.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

Four micrometer thick FFPE tissue slides were assayed for abnormal copy number variations (CNV) or other structural abnormalities by FISH in all cases. Genetic alterations in chromosome 6 (monosomy) and isochromosome 17 and CNV in MYCN, TP53, MYC genes were assessed with locus-specific probes (Supplementary Table S1), each coupled with its corresponding pericentromeric control probe, which is provided together with the target probe (Lexel, Argentina). Each FISH reaction was performed as described25. A minimum of 100 tumor nuclei were evaluated, and specimens were considered positive for abnormal CNV when the ratio between signals of the target gene and pericentromeric control signal was unbalanced. All probes were internally validated using two tissue slides which were known to contain the specific abnormality. Each FISH assay included two additional tissue slides; one with a previously characterized positive tissue section and one with a negative case to serve as positive and negative controls, respectively. Sections were evaluated by a trained pathologist (SLC) in an AxiScopeA1 epi-fluorescence microscope and images were acquired with an Axiocam 503 color dedicated camera (Carl-Zeiss, Germany).

Molecular analysis

Material from FFPE blocks was amplified by PCR and directly sequenced by the automated Sanger method to evaluate the presence of SNVs. Total DNA was purified as described in25 and Exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene and exons 5, 6, 7, and 8 of TP53 gene were amplified in 25 µl final volume with GoTaq G2 DNA Polymerase (Promega, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers and annealing temperatures for each amplified region are described in Supplementary Table S2. Post-PCR DNA purification and sequencing reactions were performed as described in25.

NanoString

Following RNA isolation from FFPE, the NanoString nCounter assay was performed at the Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory, Barretos Cancer Hospital, for a subgroup of 74 patients for the mRNA expression of a 25-gene panel proposed for medulloblastoma subgrouping11. Cases with a raw gene count for GAPDH below 500 were deemed inadequate due to poor sample quality and were not included in the classification analysis.

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared test (χ²-test) or Fisher’s Exact test were used to examine the association between categorical variables and the Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables which follow a Gaussian distribution. A χ²-test of independence was used to assess the association between molecular groups of MB and the anatomic location, biological risk or all genetic alterations. Analyses were performed using Python 3 with pandas (data handling), scipy (statistical testing), seaborn and matplotlib (data visualization) libraries. Cases classified as “undetermined” and those with “not otherwise specified” (NOS) molecular status were excluded from the analysis due to lack of molecular definition. Standardized residuals (SR) were calculated to identify which specific combinations of variables contributed significantly to the χ²-test statistic. Standardized residuals greater than + 2 or less than − 2 (>|2|) were considered statistically significant. Heatmaps were generated to visualize the standardized residuals. Overall survival was defined as time from diagnosis to death or the time to last follow-up for periods ≥ than 60 months. Survival curves were performed by Kaplan–Meier method, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) Test, with GraphPad Prism v5.01 (GraphPad Software, USA). All P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Data availability

Data generated and/or analyzed in this study is fully available at Argentina´s National Research Council Data Bank: *Repositorio Institucional CONICET Digital* following the URL http://hdl.handle.net/11336/264198.

References

Manfreda, L., Rampazzo, E., Persano, L., Viola, G. & Bortolozzi, R. Surviving the hunger games: metabolic reprogramming in Medulloblastoma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 215, 115697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115697 (2023).

Moreno, F., Chaplin, M., Kumcher, I., Goldman, J. & Montoya, G. 1 1-119 (Instituto Nacional del Cáncer y Ministerio de Salud Argentina, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2021).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 23, 1231–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/noab106 (2021).

Northcott, P. A., Dubuc, A. M., Pfister, S. & Taylor, M. D. Molecular subgroups of Medulloblastoma. Expert Rev. Neurother. 12, 871–884. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.12.66 (2012).

Jackson, K. & Packer, R. J. Recent advances in pediatric Medulloblastoma. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 23, 841–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-023-01316-9 (2023).

Moreno, D. A. et al. High frequency of WNT-activated Medulloblastomas with CTNNB1 wild type suggests a higher proportion of hereditary cases in a Latin-Iberian population. Front. Oncol. 13, 1237170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1237170 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Medulloblastoma targeted therapy: from signaling pathways heterogeneity and current treatment dilemma to the recent advances in development of therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 250, 108527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2023.108527 (2023).

Barateiro, L. et al. Somatic mutational profiling and clinical impact of driver genes in Latin-Iberian medulloblastomas: towards precision medicine. Neuropathology: Official J. Japanese Soc. Neuropathology. 45, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/neup.12979 (2025).

Holmberg, K. O., Borgenvik, A., Zhao, M., Giraud, G. & Swartling, F. J. Drivers underlying metastasis and relapse in medulloblastoma and targeting strategies. Cancers 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16091752 (2024).

Li, B. K., Al-Karmi, S., Huang, A. & Bouffet, E. Pediatric embryonal brain tumors in the molecular era. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 20, 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737159.2020.1714439 (2020).

Leal, L. F. et al. Reproducibility of the NanoString 22-gene molecular subgroup assay for improved prognostic prediction of Medulloblastoma. Neuropathology: Official J. Japanese Soc. Neuropathology. 38, 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/neup.12508 (2018).

Koch, A., Childress, A., Vallee, E. & Steller, A. The current landscape of molecular pathlogy for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric Medulloblastoma. J. Mol. Pathol. 6, 11 (2025).

Kumar, R., Liu, A. P. Y. & Northcott, P. A. Medulloblastoma genomics in the modern molecular era. Brain Pathol. 30, 679–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12804 (2020).

Dhanyamraju, P. K., Patel, T. N., Dovat, S. & Medulloblastoma Onset of the molecular era. Mol. Biol. Rep. 47, 9931–9937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-020-05971-w (2020).

Bagchi, A., Dhanda, S. K., Dunphy, P., Sioson, E. & Robinson, G. W. Molecular classification improves therapeutic options for infants and young children with Medulloblastoma. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Network: JNCCN. 21, 1097–1105. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.7024 (2023).

Nalita, N., Ratanalert, S., Kanjanapradit, K., Chotsampancharoen, T. & Tunthanathip, T. Survival and prognostic factors in pediatric patients with Medulloblastoma in Southern Thailand. J. Pediatr. Neurosciences. 13, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.4103/jpn.JPN_111_17 (2018).

Rutkowski, S. et al. Survival and prognostic factors of early childhood medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4961–4968. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2299 (2010).

Sheng, H. et al. Heterogeneity and tumoral origin of Medulloblastoma in the single-cell era. Oncogene 43, 839–850. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-024-02967-9 (2024).

Funakoshi, Y., Sugihara, Y., Uneda, A., Nakashima, T. & Suzuki, H. Recent advances in the molecular Understanding of Medulloblastoma. Cancer Sci. 114, 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.15691 (2023).

Northcott, P. A. et al. Medulloblastoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 5 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0063-6 (2019).

Zhukova, N. et al. Subgroup-specific prognostic implications of TP53 mutation in Medulloblastoma. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 31, 2927–2935. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.5052 (2013).

Cho, H. W. et al. Risk stratification of childhood medulloblastoma using integrated diagnosis: discrepancies with clinical risk stratification. J. Korean Med. Sci. 37, e59. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e59 (2022).

Michalski, J. M. et al. Children’s oncology group phase III trial of Reduced-Dose and Reduced-Volume radiotherapy with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed Average-Risk Medulloblastoma. J. Clin. Oncology: Official J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 39, 2685–2697. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.02730 (2021).

Colli, S. L. et al. Prevalent genetic alterations in pediatric thyroid carcinoma: insights from an Argentinean study. PLoS One. 20, e0323271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0323271 (2025).

Colli, S. L. et al. Molecular alterations in the integrated diagnosis of pediatric glial and glioneuronal tumors: A single center experience. PLoS One. 17, e0266466. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266466 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Juan Paladea for graphical assistance during figure production and Ms. Veronica Lapido for her technical assistance in the laboratory.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Argentinian National Institute of Cancer (INC) of the National Ministry of Health (Res 83/2020), grants from the Argentinian National Agency for Research Promotion, Technological Development and Innovation (Agencia I + D + i) of the National Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (PICT 2020 No. 854) and (PICT 2021 No. 121) and by Brazilian Ministry of Health (MoH), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development - CNPq, Brazil, and Brazilian National Program of Genomics and Precision Health – Genomas Brasil (MS-SECTICS-Decit/CNPq n° 16/2023- INOVACRIANÇA - Inovação terapêutica em crianças com tumores sólidos: uma jornada de precisão). There was no additional external funding received for this study. E.N.DM, M.A.L, and M.V.P are members of the CONICET Research Career Program. M.E.B was supported by a PhD fellowship from Agencia I + D + i.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors meet the authorship criteria and have contributed to, seen, and approved the final submitted version of the manuscript. Marisa E. Boycho: Methodology; Visualization; Validation; Formal analysis; Data curation.Sandra L. Colli: Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Formal analysis. Silvia B. Christiansen: Methodology; Visualization; Validation.Franco M. Mangone: Methodology; Visualization.Murilo Bonatelli: Methodology; Software; Validation; Visualization; Formal analysis.Flávia de Paula: Validation; Visualization; Methodology.Mercedes García Lombardi: Validation; Visualization.Agostina Attardo: Validation; Data curation; Methodology; Visualization.Elena N. De Matteo: Validation; Visualization. Hernán J. García Rivello: Visualization.Rui M. Reis: Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Data curation; Supervision. Mario A. Lorenzetti: Conceptualization; Investigation; Funding acquisition; Writing—original draft; Writing - review & editing; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Validation; Visualization. María Victoria Preciado: Conceptualization; Investigation; Funding acquisition; Writing—original draft; Visualization; Validation; Writing - review & editing; Methodology; Formal analysis; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Data curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boycho, M.E., Colli, S.L., Christiansen, S.B. et al. An integrated approach to molecular profiling supports precision diagnosis of pediatric medulloblastoma in Argentina amid the resource-constrained setting. Sci Rep 16, 2113 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31809-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31809-1