Abstract

Mental training is an integral component of physical preparation, and goal setting is among the most widely applied mental techniques in sport. The present study investigated functional changes in soccer passing performance using multiple and separate goal-setting strategies, based on the SMART principle. Fifty male participants (Mage = 23.12, SD = 2.40 years; age range = 18–28), with no prior experience in organized soccer training, volunteered for the study. A semi-experimental (quasi-experimental) pretest–posttest design with a control group was employed. Participants were systematically assigned to one of five groups: multiple goal setting, process, performance, outcome, or control. Each training session consisted of soccer passing practice combined with goal setting tasks. Following a pretest, participants completed 15 training sessions; an acquisition test was administered immediately after training, followed by retention and transfer tests 72 h later. The results revealed significant improvements across groups in the acquisition phase, though no significant between-group differences were observed. In contrast, significant effects emerged in the retention phase, F(4, 45) = 5.56, p < .001, η2 = 0.33, and in the transfer phase, F(4, 45) = 8.18, p < .001, η2 = 0.42. All goal-setting intervention groups outperformed the control group, with the multiple goal-setting group achieving the highest performance scores. In conclusion, the application of goal-setting strategies based on the SMART principle enhanced long-term retention and transfer of soccer passing skills, with multiple goal setting showing advantages over other approaches. Findings suggest that coaches and sport psychologists would benefit from integrating multiple goal-setting strategies into training protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To increase performance and learning, coaches need psychological interventions1, especially in soccer2. One of these interventions is goal setting3, that creating goals are focused on the mechanism of how a person can set goals and how the set goals can be empowering and motivating4,5. Goal setting is a motivational theory that effectively energizes and motivates athletes to become more productive and efficient6,7. The goal setting by the athletes illustrates intrinsic or extrinsic motivation, which depends on whether the goals are internalized and personalized or not8,9.

Locke and Latham’s theory4,10 in this context believes that increasing energy11 and performance in a person is achieved in four ways: First, goal setting guides individual to focus their efforts on the desired performance related to the goal and ignore irrelevant activities12. Second, goal setting energizes people and allows them to give their best effort13. Third, the goals affect the continuity of performance14. The last point is that goal setting develops the discovery and development of performance-related strategies4,10,15.

Three main types of goal setting are identified and used in sport psychology15, which are: (a) outcome goals that focus on the results of sports events and require some different types of interpersonal comparisons3,16. (b) Performance goals specify the end product of behavior that will be achieved by an individual relatively independently of other athletes and teammates15,16. (c) Process goals focus on specific behaviors that are expressed during implementation17,18.

There is another approach to goal setting that is used in multiple or combined manners19,20. The main advantage of the multiple goal-setting approaches is that it neutralizes the potential negative effects due to the failure to achieve one goal performance by achieving other goals20,21. Coaches believe that setting multiple and combined goals is the most effective method22,23. Research by Kolovelonis et al. (2011), however, showed opposite results and did not observe a difference between the result-oriented and performance-oriented goal-setting groups alone with the combined group in the performance of students24. However, few studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of combined and multiple goals, and more research is needed to investigate this issue.

Previous research illustrates that participants in the performance goal-setting group (experimental group) showed greater improvements in performance compared to the control group24. Also, research in the field of goal setting shows that goal setting is one of the most common components of behavioral interventions25 and promotes participation and keep physical activity26,27, also as a suitable psychological education technique28 and a suitable strategy to reduce the decline from mental warm-up 3 are useful, and goal setting is the most used strategy among inactive adults23,27.

Various principles have been proposed by researchers for effective goal setting29,30, one of which is the SMART principle, and this principle ensures that all the basic principles are present in goal setting31. According to the SMART principle, goals should be specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and time-bound, but their use depends on the learning stages of the learner16,32. While SMART goal setting is widely implemented in the field of education, it has rarely been used in the field of physical activity16,33, which was first reported by MacDonald et al. (in 2015) and concluded that if SMART goal setting is presented, preparation Aerobics of young people improves31.

Nevertheless, it seems that attention to the characteristics, different styles of goal setting, and having a general framework is the most appropriate way when choosing goal setting1,16. To obtain this goal in this study, different types of goal setting on learning soccer pass skills have been attempted to focus on the SMART principle and concerning different goal setting styles, so that by using the results, learners, coaches, and sports psychologists in to help in better planning and choosing appropriate goal setting. Therefore, the present study trying to show what is the effect of separate and multiple types of goal setting based on the SMART principle on learning soccer pass skills?

Methods

Participants and procedures

Fifty male participants (Mage = 23.12, SD = 2.40; age range 18–29 years) who had no prior experience in organized soccer training or regular/professional participation in other sports were recruited. Also, they did not report to participate in any organized sport activities.

Based on their first test of passing at the first stage, they were systematically assigned into five conditions. The study protocol has been approved by Institutional Review Board of the University of Tabriz.

Fifty males voluntarily participated in the study and were assigned to five groups based on their demographic information (see Appendix). The required sample size was determined using G*Power software version 3.1.9.434 (www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und arbeitspsychologie/gpower) with a priori power analysis (large effect size = 65, p = .05, power = 0.95), which indicated that a minimum of 50 participants would be sufficient to detect meaningful group differences. In addition, to provide further clarity regarding the magnitude of the observed differences, we calculated effect sizes in pairwise comparisons using Cohen’s d. This procedure ensured that the study design was statistically powered and that effect sizes were transparently reported.

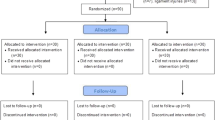

Participants were assigned to five groups (ten participants in each group): performance goal setting, process goal setting, outcome goal setting, multiple goal setting, and control group. Groups were allocated systematically: participants were first ranked based on baseline performance scores, then sequentially assigned to each group to ensure balanced distribution across conditions. The study protocol received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Tabriz on 2023.02.01, which is approved by the Faculty of Physical Education and Sport Sciences at the University of Tabriz (ID IR.TABRIZU.REC.1402.001) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations also followed the ethical guidelines set out in the Declaration of Helsinki35. All participants agreed to participate and signed the informed consent.

Task and design

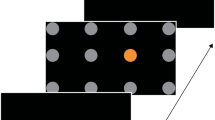

In this research, the following tools were used for taking measurements and exercises: Personal profile registration form created by the researcher (see Fig. S1). Acta Kinesiol. (2023) emphasized the importance of using valid and reliable assessment tools in team sports36. In line with this, A standard size 5 soccer ball (circumference 68–70 cm, weight 410–450 g), a standard soccer field with natural turf (length 90–120 m, width 45–90 m), and the soccer side-limb pass test (University of São Paulo Sports Training Center)37 were used in this study to ensure methodological rigor. Given the importance of using validated assessment tools38,39, the reliability of the test in previous research through a test-retest yielded an ICC of 0.71 for the side pass40. To ensure scoring consistency, all raters underwent standardized training, and inter-rater reliability was assessed (ICC = 0.75). Each participants was placed at a distance of 6 m in front of 6 metal rods with a height of 70 cm and a diameter of 2 cm, and a distance of 40 cm from each other on the soccer field. The sidekick hits the soccer ball with maximum accuracy toward the central posts. Thus, the accuracy of kicking with the inner side of the foot was considered with a score of 30 for the central gate, 20 points for the gates adjacent to the central gate, 10 points for the outermost gates, and 0 points for outside the measurement range. If the ball made contact with the bars and then passed between the two bars, the full score would be recorded. But if the ball hit the bar and did not pass through the goal, the average score between the adjacent goals was recorded41(see Fig. 1).

Procedure

At the beginning of the work and before the pre-test, the soccer pass skill was explained and performed once by the soccer coach so that the participants could see the correct way of performing the skill and would not get confused during the test, which is consistent with the emphasis on clear scientific communication in intervention research42. Then the pre-test was performed and the participants were systematically divided into five groups. The acquisition phase consisted of 15 sessions of 30 attempts (three blocks of ten attempts, one minute rest between each block and five seconds rest between each attempt in the side limb pass skill) with one day of rest (see Fig. 2).

Intervention

In this research, after explaining the general principles of goal setting and its practical application, participants were assigned to four functional goal-setting groups and one control group. The groups were defined as follows: performance goal setting (focused on improving each individual’s overall performance); process goal setting (focused on optimizing performance in the last four stages of the task); outcome goal setting (focused on achieving the highest possible points); and multiple goal setting (combined focus on both the last four stages and achieving the highest points simultaneously). All goals were structured according to the SMART principle and individualized based on each participant’s baseline performance and abilities, ensuring that the targets were specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and time-bound32,33, The goals were set and selected according to the SMART principle as follows:

-

1.

Specific – goals were individualized, taking into account each participant’s baseline performance and personal differences.

-

2.

Measurable – progress could be quantitatively tracked during training sessions.

-

3.

Action-oriented – goals were designed to guide participants’ behavior toward desired performance outcomes.

-

4.

Realistic – goals were adjusted according to each individual’s ability and potential.

-

5.

Time-bound – short-term goals were prioritized as stepping stones to long-term goals, maintaining motivation throughout the intervention.

Participants in the control group did not receive goal-setting intervention. Participants in all groups performed physical exercises separately according to their assigned group and received continuous individualized feedback, including verbal instructions, corrective guidance, and performance reinforcement tailored to their progress. All groups practiced under the same conditions, and the training schedule for all groups was before noon. Immediately after the last training session, the acquisition test in the side-limb pass skill was administered following a 5-minute rest interval, with participants having no opportunity to practice the task prior to assessment. Seventy-two hours after the acquisition test, the retention and transfer tests were conducted, with the passing distance increased to 8 m for each participant.

Homogeneity of variances and normality of the data were examined and confirmed using Levene’s test and the Shapiro-Wilk test, respectively. To compare the groups in the pre-test, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. For the acquisition phase, data were analyzed using a mixed ANOVA (5 × 2) with 5 groups and 2 phases (pre- and post-test) to examine the main effects of group, phase, and their interaction, following recommended procedures for intervention studies in sports43. For the retention and transfer phases, one-way ANOVA was used to compare the groups. Tukey’s post hoc test was applied to determine pairwise differences between groups at different stagesa44. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 22 software (https://www.ibm.com/products/spss) with a significance level of p < .05. Graphs were drawn using Origin Pro version 8.5 software (https://www.originlab.com).

Results

Means and standard deviation in four stages of pre-test, post-test, retention, and transfer across condition are appeared in Table 1; Fig. 3.

The univariate distribution of the data firstly through Shapiro-Wilk tested, and the results showed that the data normally distributed across all stages of pre-test, post-test, retention, and transfer in five conditions.

To investigate differences in soccer pass performance during the acquisition phase, a mixed ANOVA (5 × 2) with 5 groups (performance, process, outcome, multiple, and control) and 2 phases (pre- and post-test) was conducted. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of phase (F (1, 10) = 125.58, p < .001, η2 = 0.96), indicating that all groups improved from pre- to post-test. The main effect of group (F (1, 4) = 0.13, p > .001, η2 = 0.01) and the phase × group interaction (F (1, 45) = 0.46, p > .001, η2 = 0.03) were not significant. Although the interaction was not statistically significant, descriptive data show that the goal-setting groups had higher mean improvements than the control group.

In the following, the difference between the goal-setting groups of process, performance, outcome, multiple and control group were discussed in the retention and transfer phase. According to the results of the one-way analysis of variance showed that there is a significant difference between the groups in both the retention F (4, 45) = 5.56, p < .001, η2 = 0.33 and transfer phases F (4, 45) = 8.18, p < .001, η2 = 0.42.

The results of Tukey’s post hoc test show that the average difference between the Outcome and control (p = .05, Cohen’s d = 0.93, mean difference = 1.55, 95% CI [0.00, 3.1]), performance and control (p = .01, Cohen’s d = 1.43, mean difference = 1.70, 95% CI [0.27, 3.12]), multiple and control (p = .001, Cohen’s d = 1.57, mean difference = 2.25, 95% CI [0.69, 3.80]) in the retention test is significant, but there was no significant difference between the process goal-setting groups with the control group (p = .23, Cohen’s d = 0.76, mean difference = 1.20, 95% CI [-0.22, 2.62]) and other goal setting groups and the multiple goal setting group It had the highest average scores among the groups (Mean = 24.30, SE = 0.35). Tukey’s test also shows that in the transfer test, the average difference between the process and control (p = .094, Cohen’s d = 1.40, mean difference = 1.15, 95% CI [0.39, 1.90]), performance and control (p = .001, Cohen’s d = 1.89, mean difference = 1.30, 95% CI [0.54, 2.05]), outcome and control (p = .007, Cohen’s d = 1.85, mean difference = 1.55, 95% CI [0.79, 2.30]), multiple and control (p = .001, Cohen’s d = 2.27, mean difference = 2.05, 95% CI [0.79, 3.30]) is significant, and the post hoc test shows that there is no significant difference between any of the goal-setting groups in a two-by-two comparison, and the highest mean Scores were recorded for the multiple goal setting group (Mean = 24.55, SE = 0.26).

Discussion

The current research was conducted to examine the effects of separate and multiple goal-setting on learning soccer passing skills, with a focus on the SMART principle. The results of the present research showed that the participants of the goal-setting groups performed better than the control group in different stages of acquisition, retention, and transfer. The results of the present research showed that the participants of the goal-setting groups performed better than the control group across different phases of acquisition, retention, and transfer. These results highlight the importance of structured and goal setting interventions for improving motor learning in soccer. Similar to our findings, Kale et al. (2023) demonstrated that preparatory strategies can significantly affect post-activity performance, supporting the notion that both physical and psychological approaches are essential for optimizing performance and skill acquisition45. The goal-setting groups had higher mean scores in the acquisition stage, although this difference was not statistically significant, but in the subsequent stages of learning, i.e., retention and transfer, the differences became statistically significant. The results of the findings of the current research with the results of the research of Crotts6, Swann et al.1,23, Brinkman et al.28 all of which were consistent with the fact that goal setting improves performance.

In a review, Swann et al. interviewed the theory of goal-setting intending to update physical activity, in this review, Swann et al. state that specific performance goals are considered as a tool to increase physical activity, and goal-setting performance is context-dependent23. Also, in research, Brinkman et al. (2019) investigated the effect of using goal setting to increase the self-efficacy and performance of athletes after an injury28. Finally, Brinkman et al. (2020) concluded that goal-setting may be an effective psychological training technique to enhance self-efficacy and improve athletes’ performance following sports-related injuries, and they suggested that combining goal-setting with rehabilitation is more beneficial for patients’ performance than rehabilitation alone28. In another study, Brewer et al. (2019) investigated a study titled mental warm-up for athletes3. The purpose of this research was to develop an evaluation of a five-minute structured mental warm-up including goal-setting aspects. This study showed that the implementation of mental warm-up is appropriate with greater preparation for implementation and increased performance3. In the third part of the study, Brewer et al. (2019) reported that male high school soccer players used mental warm-ups daily during a competitive season and rated it as acceptable (although not as much as a physical warm-up) at the beginning, middle, and end of the season. The findings showed that goal-setting as a mental warm-up tool is both acceptable to athletes and potentially useful in helping athletes prepare for training and competition3.

The function of goal setting on performance can be justified using Locke and Latham’s goal-setting theory (2002). This theory states that the effectiveness of goal setting is achieved through four mechanisms: guidance, increased effort, persistence, and strategy discovery4. Building on this framework, multiple goal setting, which simultaneously focuses on performance, process, and outcome goals, may provide superior benefits by engaging several cognitive and motivational mechanisms simultaneously. According to the principles of motor learning, targeting different aspects of performance (e.g., technique, accuracy, and outcome) can enhance skill acquisition, promote retention, and improve the transfer of learning. Integrating multiple goal types aligns psychological interventions with established motor learning frameworks, as emphasized by Fessi et al. (2016), there by supporting more comprehensive improvements in sports skill performance46. The findings of the present study should be interpreted in light of the inconsistent evidence on goal setting in sport. Jeong et al. (2023) demonstrated that the application of Goal Setting Theory principles has produced mixed results, particularly regarding goal characteristics (e.g., difficulty, specificity) and moderators (e.g., feedback, commitment). In this regard, our study emphasizes multiple goal setting, suggesting that the concurrent use of different types of goals may help reduce such inconsistencies and provide a stronger basis for designing individualized interventions in applied sport contexts16, The findings of the present study can also be interpreted in the context of developments in Goal Setting Theory since 1990. Savon et al. (2021) highlighted that distinguishing between performance goals and learning goals is critical, and that relying solely on performance goals may have negative consequences, particularly for beginners. Accordingly, the present study emphasizes the importance of a multiple-goal approach, suggesting that integrating performance and learning goals can offer a more comprehensive and individualized framework for designing sport interventions23. Howlett (2019) also believes that goal setting is useful for promoting and sustaining participation in physical activity and is a good strategy for participants27 Durdubas et al. (2020) also conducted a study with the aim of the effect of goal-setting intervention during the season on the performance of young professional basketball players26. The findings showed that the goal-setting groups performed better than the control group during the research process. Kolovelonis et al. (2012) investigated the effect of goal-setting and self-talk on movement skills in physical education classes in schools17. The results of the study showed that students who use performance goals in self-talk ultimately perform better than other groups.

Vidage and Borton (2010) researched to investigate the effect of a goal-setting program on the psychological factors of tennis players8. In this study, the effect of eight weeks of goal-setting intervention on the motivation, self-confidence, and performance of tennis players was investigated. During the eight weeks, all six players showed improvements in the measures of motivation, self-confidence, and performance. In addition, the qualitative results can be increased the influence of the intervention, so that all six athletes consistently reported that goal setting was useful in increasing their motivation, self-confidence, and performance.

On the other hand, the results of this research conflict with Kolovelonis’ results (2011), which showed that there is no difference among other groups24. One of the most important reasons for the inconsistency is that only one training session is used in their research, which seems that this number of training sessions cannot show the main effect of goal setting better. However, 15 training sessions were used in this study. In addition, the type of goal setting in the research of Kolovelonis et al. is one of the other discrepancies compared to the present study. A general type of goal setting was used based on recent findings which may not be appropriate and effective in the wake of using one standard for all. But in the current research, attention was paid to individual differences and people chose goals freely and self-controlled.

The distinction and superiority of the present research compared to previous studies were in the use of multiple and separate goal setting in the form of the SMART principle31,32. As the results showed, the use of goal setting in the form of SMART increases performance in different stages of learning compared to other groups.

Study limitation and future directions

While the performance of all groups improved in the acquisition phase, the results did not show significant differences between groups in the acquisition phase. But later on, in the retention and transfer stages, there was a significant difference between the groups, and the goal-setting groups improved their performance compared to the control group and showed a significant difference. However, the current study had some limitations, and the authors suggest that this study be investigated in different age groups of males and girls in different sports. In addition, the current study controlled for a major limitation of previous research, namely that participants used only one type of goal setting24. In this research, several types of goal setting were used. Also, in this research, we tried to control the limitations of the previous research by including participants without professional experience in the intervention through the questionnaire. McDonald et al.‘s (2015) research showed that using the SMART model has advantages31,32. Therefore, this study provides empirical evidence that using the SMART model is a valuable approach. It is suggested that future studies use the SMART model for better goal setting effectiveness and also to have a specific framework.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size (n = 10) limits the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Second, the study design was non-blinded, which may introduce potential bias in reporting and interpreting outcomes. Third, as the study focused on a specific group of athletes in a controlled applied setting, caution is warranted when generalizing the results to broader samples. Recognizing these limitations underscores the need for future research involving larger samples, blinded designs, and more diverse athletic contexts to strengthen the robustness and applicability of goal-setting interventions.

Conclusion

The present study provides evidence that multiple goal setting compared to single goal setting leads to a greater increase in learning the skill of limb side pass. In addition, a key new finding was that if goal setting is used in a specific framework, which in this research used the SMART principle, it will lead to better results. Finally, it should be mentioned that based on the results of the current research and the contradictions in the reviewed studies, it seems that perhaps the most appropriate way to create goal-setting programs is to pay a lot of attention to the characteristics, preferences, and styles of goal setting10,16. Coaches would increase athletes’ performance by focusing on multiple goals and applying SMART principles. Designing both performance and learning goals simultaneously, while considering athletes’ individual characteristics and needs, allows for personalized interventions and increases their effectiveness. Integrating research into practice, as highlighted by Martinelli et al. (2024), emphasizes the importance of applying evidence-based strategies to improve athlete outcomes47. Implementing SMART goals ensures that objectives are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound, providing athletes with clear direction and motivation. Applying multiple goals in a SMART framework enables coaches and sport psychologists to design and implement training and psychological programs more effectively, combining psychological and physiological strategies to enhance motor learning and performance48 .

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Williamson, O., Swann, C., Jackman, P. C., Bennett, K. J. & Bird, M. D. It’s not handcuffing the athlete to success or failure: sport psychology practitioners’ use of nonspecific goals in applied contexts. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2025, 1–22 (2025).

Shokri, S., Aghdasi, M. T. & Behzadniaa, B. The Effect of Self-Controlled and Coach-Controlled Performance Goal Setting on Soccer Passing Skill Learning: Application of Choice Theory. J. Sport. Mot. Dev. Learn. 15, 19–30 (2023).

Brewer, B. W., Haznadar, A., Katz, D., Van Raalte, J. L. & Petitpas, A. J. A mental warm-up for athletes. Sport Psychol. 33, 213–220 (2019).

Locke, E. A. & Latham, G. P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 57, 705 (2002).

Pincus, J. D. Goals as motives: implications for theory, methods, and practice. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 59, 22 (2025).

Shokri, S., Aghdasi, M. T. & Behzadniaa, B. Investigating Self-Control Approaches in Learning and Sports Motivation; Emphasizing the Role of Goal Setting. Mot. Behav. 17, 17–34 (2025).

de Jong, B., Cornelissen, F., Jansen in de Wal, J. & Peetsma, T. Chasing the goal (s): how a goal-Setting intervention influences transfer Motivation, its antecedents and transfer of training for different training types. Eur. J. Work Organiz. Psychol. 34, 188–200 (2025).

Vidic, Z. & Burton, D. The roadmap: examining the impact of a systematic goal-setting program for collegiate women’s tennis players. Sport Psychol. 24, 427–447 (2010).

Mikami, Y. Relationships between goal setting, intrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy in extensive reading. Jacet J. 61, 41–56 (2017).

Locke, E. A. & Latham, G. P. The development of goal setting theory: a half century retrospective. Motivation Sci. 5, 93 (2019).

Steegh, R., Van De Voorde, K., Paauwe, J. & Peeters, T. The agile way of working and team adaptive performance: a goal-setting perspective. J. Bus. Res. 189, 115163 (2025).

Garner, L. D., Mohammed, R. & Robison, M. K. Setting specific goals improves cognitive effort, self-efficacy, and sustained attention. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. (2025).

Anandam, T. A Comparison of Goal-Oriented Guided Mental Imagery versus Goal Setting Interventions for Increasing Physical Activity Levels in Young, Inactive Adults with Overweight or Obesity: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial, Swinburne (Springer, 2025).

Heidrich, B. & Vajdovich, N. In Conference on Organizational Science Development Human Being, Artificial Intelligence and Organization 273 (2024).

Bird, M. D., Swann, C. & Jackman, P. C. The what, why, and how of goal setting: a review of the goal-setting process in applied sport psychology practice. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 36, 75–97 (2024).

Jeong, Y. H., Healy, L. C. & McEwan, D. The application of goal setting theory to goal setting interventions in sport: a systematic review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 16, 474–499 (2023).

Kolovelonis, A., Goudas, M. & Dermitzaki, I. The effects of self-talk and goal setting on self-regulation of learning a new motor skill in physical education. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 10, 221–235 (2012).

McCarthy, P. J. & Gupta, S. Set goals to get goals: sowing seeds for success in sports. Front. Young Minds. 10, 684422 (2022).

McEwan, D. et al. The effectiveness of multi-component goal setting interventions for changing physical activity behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 10, 67–88 (2016).

Gargano, A. & Rossi, A. G. Goal setting and saving in the fintech era. J. Finance. 79, 1931–1976 (2024).

de Vreugd, L., van Leeuwen, A. & van Der Schaaf, M. Students’ use of a learning analytics dashboard and influence of reference frames: goal Setting, Motivation, and performance. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 41, e70015 (2025).

Arvinen-Barrow, M., Hemmings, B. & Hansen, M. A. The Psychology of Sport Injury and Rehabilitation 203–215 (Routledge, 2024).

Swann, C. et al. Updating goal-setting theory in physical activity promotion: a critical conceptual review. Health Psychol. Rev. 15, 34–50 (2021).

Kolovelonis, A., Goudas, M. & Dermitzaki, I. The effect of different goals and self-recording on self-regulation of learning a motor skill in a physical education setting. Learn. Instruct. 21, 355–364 (2011).

Michie, S., West, R., Sheals, K. & Godinho, C. A. Evaluating the effectiveness of behavior change techniques in health-related behavior: a scoping review of methods used. Transl. Behav. Med. 8, 212–224 (2018).

Durdubas, D., Martin, L. J. & Koruc, Z. A season-long goal-setting intervention for elite youth basketball teams. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 32, 529–545 (2020).

Howlett, N., Trivedi, D., Troop, N. A. & Chater, A. M. Are physical activity interventions for healthy inactive adults effective in promoting behavior change and maintenance, and which behavior change techniques are effective? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Behav. Med. 9, 147–157 (2019).

Brinkman, C., Baez, S. E., Genoese, F. & Hoch, J. M. Use of goal setting to enhance self-efficacy after sports-related injury: a critically appraised topic. J. Sport Rehabil. 29, 498–502 (2019).

Weintraub, J., Cassell, D. & DePatie, T. P. Nudging flow through ‘SMART’goal setting to decrease stress, increase engagement, and increase performance at work. J. Occup. Organiz. Psychol. 94, 230–258 (2021).

Ogbeiwi, O. General concepts of goals and goal-setting in healthcare: a narrative review. J. Manage. Organ. 27, 324–341 (2021).

McDonald, S. M. & Trost, S. G. The effects of a goal setting intervention on aerobic fitness in middle school students. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 34, 576–587 (2015).

Relitz, A. S. M. A. R. T. Goal-Setting on Behaviors to Enhance Intrinsic Motivation for Exercise: A Pilot Study with Orangetheory Fitness Participants (Springer, 2025).

Bexelius, A., Carlberg, E. B. & Löwing, K. Quality of goal setting in pediatric rehabilitation—a SMART approach. Child Care Health Dev. 44, 850–856 (2018).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A. & Lang, A. G. Statistical power analyses using G* power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods. 41, 1149–1160 (2009).

Association, W. T. W. M. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. WMA: Ferney-Voltaire, France (2024).

Uribarri, H. G. et al. Validity of a new tracking device for futsal match. Acta Kinesiol. 17, 17–21 (2023).

Teixeira, L. A., Silva, M. V. & Carvalho, M. Reduction of lateral asymmetries in dribbling: the role of bilateral practice. Laterality: Asymmetr. Body Brain Cogn. 8, 53–65 (2003).

Hraste, M., Jelaska, I. & Clark, C. C. Analysis of expert’s opinion of optimal beginning age for learning technical skills in water Polo. Acta Kinesiol. 17, 35–41 (2023).

Padulo, J. et al. Effects of gradient and speed on uphill running gait variability. Sports Health. 15, 67–73 (2023).

Hoseini, M. & Sohrabi, M. A. Study on bilateral transfer symmetry of cognitive & motor components in soccer kicking. J. Mot. Behav. 6, 169–180 (2014).

Hoseini, M., & Sohrabi, M. A study on bilateral transfer symmetry of cognitive. & motor components in soccer kicking. Motor Behav. 6, 169–180 (2014).

Spriggs, M. Children and bioethics: clarifying consent and assent in medical and research settings. Br. Med. Bull. 145, 110–119 (2023).

Migliorini, F. et al. Knee osteoarthritis, joint laxity and proms following conservative management versus surgical reconstruction for ACL rupture: a meta-analysis. Br. Med. Bull. 145, 72–87 (2023).

Dhahbi, W. et al. 4–6 repetition maximum (RM) and 1-RM prediction in free-weight bench press and Smith machine squat based on body mass in male athletes. J. Strength. Condition. Res. 38, 1366–1371 (2024).

Kale, M., Yol, Y., Tolali, A. B. & Ayaz, E. Effects of repetitive different jump pre-conditioning activities on post activity performance enhancement: effects of repetitive different jump preloads. Acta Kinesiol. 17, 55–61 (2023).

Fessi, M. et al. Reliability and criterion-related validity of a new repeated agility test. Biol. Sport 33, 159–164 (2016).

Marinelli, S., La Greca, S., Mazzaferro, D. & Russo, L. Giminiani, R. A focus on exercise prescription and assessment for a safe return to sport participation following a patellar tendon reconstruction in a soccer player. Acta Kinesiol. 18, 13–23 (2024). Di.

Villanueva-Guerrero, O. et al. Analysis of the effects of the transitional period on performance parameters in young soccer players. Acta Kinesiol. 17, 4–11 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study also consider it necessary to thank the referees and participants who collaborated in this study.

Funding

This research is supported by the research grant of the University of Tabriz (grant number:2024.11.5/2469).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saeed Shokri: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, read and approved the final manuscript Mohammad Taghi Aghdasi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, read and approved the final manuscript Behzad Behzadnia: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shokri, S., Aghdasi, M.T. & Behzadnia, B. Examining performance changes using multiple goal setting with a focus on the SMART principle. Sci Rep 16, 1476 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31819-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31819-z