Abstract

Human excitatory neurons programmed through neurogenin-2 (NGN2) overexpression are widely used to model brain disorders in vitro. Although growth factors (GFs) such as BDNF, GDNF, NT3 and CNTF are commonly included in differentiation protocols, their individual and combined effects on neuronal survival, morphology and function remain insufficiently characterized. Here, we systematically examined the impact of these GFs, alone or in combination, on the development and maturation of NGN2-neurons. We also compare network activity of neurons maintained in Neurobasal medium (NBM) versus BrainPhys (PB). We show that BDNF or GDNF alone were sufficient to support neuronal survival and morphological complexity, whereas functional maturation, including network activity, required CNTF. Furthermore, BP supported neuronal development and function comparable to NBM, provided appropriate supplementation. Together, our results show that CNTF in combination with either BDNF or GDNF provides the most effective support for both structural and functional maturation of NGN2-neurons derived from male induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These findings offer a better understanding of how GF supplementation shapes neuronal development and provide a framework for optimizing human neuron culture conditions in disease modeling and drug discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons have become a powerful platform for modelling neurological disorders and studying neuronal physiology in vitro. Recent advances in differentiation protocols have significantly improved the reproducibility and scalability of these models, enabling the generation of distinct neuronal subtypes and broadening their utility in neuroscience research1. One of the most widely adopted methods is the forced expression of the transcription factor neurogenin-2 (NGN2), which rapidly and efficiently drives iPSCs toward a glutamatergic excitatory fate2.

To promote differentiation and maturation of NGN2-neurons, most protocols include supplementation of neurotrophic growth factors (GFs). These factors are critical for promoting neuronal survival and differentiation3,4, but also for regulating key aspects of morphology and function through activation of distinct intracellular signaling pathways4. Despite their widespread use, the individual and combined effects of these GFs on neuronal phenotypes are not well understood, limiting the interpretability and reproducibility of experimental outcomes and potentially inflating experimental costs unnecessarily.

Among the most frequently used GFs are brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)1,5,6,7. BDNF, a member of the neurotrophin family, plays a central role in neuronal development, including axonal and dendritic growth, synaptogenesis, and synaptic plasticity in both rodent models and iPSC-derived human neurons4,8,9,10,11. BDNF is sorted into large dense core vesicles (DCVs), and secreted in an activity dependent manner12. While BDNF is critical for neuronal survival during early development13, its continued presence supports neurite maintenance beyond 21 days in vitro14 and modulates synaptic efficacy via mechanisms such as long term potentiation (LTP)15,16.

GDNF, despite its name, is primarily produced by neurons during development17. Under pathological conditions, its expression is upregulated in astrocytes18,19. Originally identified as a survival factor for dopaminergic neurons20, GDNF also supports other cell types, including motor neurons21. Like BDNF, GDNF is packaged into DCVs and secreted in response to neuronal activity22. It promotes synaptogenesis, as GDNF null mutant mice show reduced presynaptic protein localization and fewer presynaptic puncta23.

Other GFs used in some NGN2-neuron protocols are neurotrophin-3 (NT3)1,5 and, less commonly, ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF)6,24,25. NT3 and CNTF are often combined with BDNF and/or GDNF1,6. NT3, a member of the same neurotrophin family as BDNF, supports neuronal survival15 and synaptogenesis26, but activates different downstream signaling pathways4. Unlike BDNF, NT3 does not promote morphological differentiation in vitro13,15. CNTF, a neurotrophic cytokine predominantly expressed by astrocytes27,28, promotes astrocyte differentiation29, activation30, and exerts neuroprotective effects under injury or disease conditions31,32,33.

Most NGN2-neurons are maintained in Neurobasal medium (NBM) supplemented with B27 to promote neuronal survival5,6,24,25,34. However, NBM has previously been reported to suppress neuronal function. In contrast, BrainPhys (BP) medium was shown to support neuronal activity by better mimicking a neurophysiological environment35. In this study, we evaluated the role of BDNF, GDNF, NT3, and CNTF in shaping neuronal survival, morphology, and function. We also compared the widely used NBM with BP. We found that BDNF or GDNF alone is sufficient to support both neuronal survival and morphological maturation. However, full functional maturation, including DCV numbers, synaptic vesicle (SV) marker intensity, and spontaneous network activity, requires the combined action of multiple GFs, with CNTF being essential for maintaining network activity. Multiple GFs were similarly required to maintain functional maturation in BP media, together with B27 supplementation. Together, either BDNF or GDNF in combination with CNTF provides the most effective support for structural and functional maturation of NGN2-neurons. These findings provide insights into the roles of GF supplementation in neuronal differentiation and offer practical guidance for optimizing NGN2-neuron culture systems for both basic and translational research.

Results

BDNF and GDNF alone support neuronal survival and morphology

To assess the effects of individual and combined GFs on neuronal survival, we cultured NGN2- neurons in NBM under various GF conditions and quantified surviving cells at 2, 4 and 6 weeks in culture (WIC) as a proxy for survivability (Fig. 1A). The tested conditions included: BDNF/GDNF/CTNF (+ B/G/C), no GFs (-GF), BDNF alone (+ BDNF), GDNF alone (+ GDNF), CNTF alone (+ CNTF), and BDNF/GDNF/NT3 (+ B/G/NT3). Cultures without GFs or supplemented with CNTF alone showed a marked reduction in surviving neurons by WIC2, which persisted through WIC4 and 6 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, BDNF alone was sufficient to maintain neuronal survival at levels comparable to multiple GFs. GNDF alone, or the addition of NT3 in the BDNF/GDNF combination (B/G/NT3) also maintained survival comparable to multiple GFs, but showed a trend towards decline over time (Fig. 1B, not statistically significant).

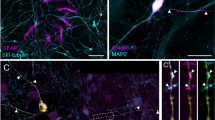

BDNF and GDNF alone are sufficient to maintain neuronal survival and morphology. (A) Schematic overview of the differentiation protocol used for NGN2-neurons. (B) Number of neurons per coverslip per condition. N numbers of individual experiments and number of coverslips in brackets: B/G/C: 3(18); no GF: 3(18); BDNF: 3(16); GNDF: 3(18); CNTF: 3(15); B/G/NT3: 3(16). (C) Representative images of autaptic NGN2-neurons stained for MAP2, maintained in culture medium containing either: B/G/C, no GFs, BDNF alone, GDNF alone, CNTF alone or B/G/NT3. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) Dendrite length at 2, 4 and 6 weeks in culture (WIC). N numbers of individual experiments and single neuron observations in brackets. WIC2: B/G/C: 3(31); no GF: 3(33); BDNF: 3(22); GNDF: 3(30); CNTF: 3(27); B/G/NT3: 3(19). WIC4: B/G/C: 3(29); no GF: 3(30); BDNF: 3(26); GNDF: 3(32); CNTF: 3(22); B/G/NT3: 3(22). WIC6: B/G/C: 3(27); no GF: 3(24); BDNF: 3(23); GNDF: 3(31); CNTF: 3(25); B/G/NT3: 3(20). (E) Dendrite length at WIC6. (F) The number of dendritic branches per condition at WIC6. Line and bar plots represent the mean ± SEM. Each dot represents an individual neuron or coverslip. Two-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis H test with Dunnett’s or Dunn’s correction, respectively: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. ns = non-significant, P > 0.05.

Next, we evaluated neuronal morphology by immunostaining for MAP2 at WIC2, 4, and 6 (Fig. 1C). Cultures lacking GFs or treated with CNTF alone exhibited significantly reduced dendritic length (Fig. 1C-E) and branching complexity (Fig. 1F). In contrast, BDNF and GDNF alone supported dendritic length and branching to levels comparable to cultures receiving multiple GFs (Fig. 1C-F). No differences in dendritic morphology were detected when either CNTF or NT3 was added to the BDNF/GDNF combination. Finally, the soma size was decreased in all conditions compared to B/G/C (Figure S1A, B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that BDNF alone is sufficient to support long-term neuronal survival and size comparable to multiple GFs.

BDNF alone supports DCV numbers

BDNF and GDNF are known to localize to DCVs and are secreted in an activity-dependent manner12,22. Given that dendrite length correlates with DCV abundance36, we next examined the effects of individual and combined GFs on DCV number and content. To this end, we immunostained NGN2-neurons for the endogenous DCV cargo chromogranin A (ChgA) at WIC2, 4 and 6 (Fig. 2A). In cultures lacking GFs, both the total number and density of ChgA-positive puncta were significantly reduced at WIC6 (Figs. 2A-C, S1C, D). Remarkably, BDNF alone was sufficient to fully restore the total number of ChgA puncta (Fig. 2B), and any single GF, including GDNF, CNTF, or NT3, was sufficient to restore ChgA puncta density to levels comparable to multiple GF conditions (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, the B/G/NT3 condition resulted in slightly lower DCV numbers than the B/G/C condition, suggesting that NT3 may negatively influence DCV abundance when combined with other GFs. DCV intensity, as a proxy for cargo loading or clustering, remained unaffected by the absence of GFs (Fig. 2D, S1E). Taken together, these results indicate that BDNF alone is sufficient to restore both the number and density of DCVs in NGN2-neurons, while the absence of GFs reduces DCV abundance. In contrast, DCV cargo loading appears largely GF-independent.

BDNF and GDNF alone are sufficient to support DCV and synapse numbers. (A) Representative images of neurons cultured in either B/G/C or no GFs stained for the dendritic marker MAP2 (blue) and DCV marker ChgA (magenta). Scale bar, 50 μm. Zooms show neurite stretches of all conditions. Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) The number of ChgA puncta per neuron. N numbers of individual experiments and single neuron observations in brackets. B/G/C: 3(27); no GF: 3(24); BDNF: 3(22); GNDF: 3(31); CNTF: 3(25); B/G/NT3: 3(20). (C) The number of ChgA puncta per um per neuron. (D) ChgA intensity normalized to the B/G/C condition per independent week. (E) Representative images of neurons cultured in either B/G/C or no GFs stained for the dendritic marker MAP2 (blue) and synaptic vesicle marker Syp1 (cyan). Scale bar, 50 μm. Zooms show neurite stretches of all conditions. Scale bar, 20 μm. (F) The number of Syp1 puncta per neuron indicative of the number of synapses. N numbers of individual experiments and single neuron observations in brackets. B/G/C: 3(27); no GF: 3(24); BDNF: 3(23); GNDF: 3(31); CNTF: 3(25); B/G/NT3: 3(20). (G) The number of Syp1 puncta per um per neuron. (H) Syp1 intensity normalized to the B/G/C condition per independent week, indicative of the number of SVs. Bar plots represent the mean ± SEM. Each dot represents an individual neuron. One-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis H test with Dunnett’s or Dunn’s correction, respectively: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. ns = non-significant, P > 0.05.

BDNF and GDNF alone support synapse numbers but not synaptic vesicle content

Previous studies have shown that BDNF, GDNF, and NT3 promote synaptogenesis23,37,38. To test the effects of these GFs on presynaptic development and SV content in NGN2-neurons, we immunostained cultures at WIC2, 4 and 6 for the SV protein synaptophysin-1 (Syp1, Fig. 2E). In the absence of GFs, the total number of Syp1-positive puncta was significantly reduced (Fig. 2F, S1F). BDNF or GDNF alone were sufficient to restore Syp1 puncta to levels comparable to cultures treated with multiple GFs, whereas CNTF alone failed to restore Syp1 puncta (Fig. 2F). Interestingly, Syp1 density (puncta per unit area) remained unchanged across conditions (Fig. 2G, S1G), suggesting that the reduction in total Syp1 puncta likely reflects reduced neuronal size or dendritic complexity rather than impaired synapse formation. In contrast, Syp1 intensity, a proxy for SV content, was significantly reduced in cultures lacking GFs or treated with only a single GF (Fig. 2H, S1H). These results demonstrate that BDNF and GDNF are sufficient to maintain normal presynaptic structures, but multiple GFs, including NT3, are required to support normal SV content. CNTF alone fails to support either normal synapse number or SV levels.

Removal of CNTF reduces spontaneous network activity

Since the absence of GFs affects multiple neuronal properties at the single cell level, we next examined how GF conditions influence neuronal network activity. To test this, we performed calcium imaging at WIC2, 4, and 6 using the genetically encoded calcium indicator jRGECO1a39 (Fig. 3A). We specifically tested whether BDNF and GDNF are also necessary to maintain spontaneous network activity.

Absence of CNTF in culture medium reduces calcium events. (A) Representative images of jRGECO signal in cultures with B/G/C or no GFs at WIC6. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Example traces of jRGECO intensity of cultures in B/G/C and no GFs. Grey lines show traces of individual cells and red lines show the average signal in the (FOV). (C) Percentage silent cells in a FOV. N numbers of individual experiments and single neuron observations in brackets: B/G/C: 6(36); no GF: 4(17); BDNF: 4(20); GNDF: 4(21); CNTF: 4(21); B/G/NT3: 6(36); B/G: 6(44); B/C: 6(39); G/C: 6(37). (D) The mean frequency of calcium events of individual neurons in a FOV. N numbers of individual experiments: B/G/C: 6(36); no GF: 4(20); BDNF: 4(21); GNDF: 4(21); CNTF: 4(21); B/G/NT3: 6(36); B/G: 6(44); B/C: 6(38); G/C: 6(37). (E) The mean frequency of network bursts in a FOV, i.e. bursts in which 80% of the neurons are active. (F) Percentage of synchronicity, defined by the percentage cells active at the same time. Bar plots represent the mean ± SEM. Each dot represents an individual neuron. Kruskal-Wallis H test with Dunn’s correction: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. ns = non-significant, P > 0.05.

At WIC6, neurons cultured in the B/G/C showed robust synchronous activity bursts lasting for several seconds (Fig. 3B, S2A). In contrast, cultures without GFs or treated with only a single GF displayed a higher percentage of silent neurons, although this difference did not reach statistical significance when compared to B/G/C conditions (Fig. 3B, C). Notably, the frequency of calcium transients in active neurons was significantly reduced in the absence of GFs, or with only a single GF present (Fig. 3D). Removal of BDNF or GDNF alone had no measurable effect on cell frequency, whereas removal of CNTF reduced cell frequency (Fig. 3D). Network-level activity, defined as synchronous bursts involving at least 80% of the neurons in the field of view, was preserved in cultures treated with B/G/C, B/G/NT3, G/C and B/C (Fig. 3E). In contrast, cultures lacking all GFs failed to exhibit coordinated bursts and showed significantly reduced network synchrony, quantified as the average percentage of neurons active simultaneously within a given time window (Fig. 3F). To rule out that reduced network activity in B/G cultures (i.e. lacking CNTF) was due to lower cell density, we quantified the number of neurons per field of view (FOV) in calcium-imaged areas. No significant difference in the number of neurons per FOV was observed between B/G and B/G/C conditions (Figure S2B). Together, these findings indicate that while BDNF and GDNF are sufficient to support many single-cell properties, CNTF plays a unique and essential role in sustaining spontaneous network activity and synchrony in NGN2-neuronal cultures.

Neurobasal and BrainPhys + B27/GFs support neuronal survival and activity equally well

NBM has been reported to suppress neuronal activity35, while BP medium contains more physiological ion concentrations (e.g. Na+, Cl−, K+) and was designed to better support spontaneous neuronal firing35. To assess whether BP improves network functionality in NGN2-neurons, we cultured neurons in BP under various supplementation conditions and performed calcium imaging at WIC6 (Fig. 4B). Neurons were plated at DIV4 in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and BP, followed by replacement with 100% BP at DIV10, with or without B27 and/or GFs (Fig. 4A).

BrainPhys medium + B27/GFs supports neuronal activity comparable to NBM. (A) Schematic overview of the differentiation protocol used for BrainPhys medium. Neurons were plated in half DMEM/half BrainPhys with or without supplementation. At DIV10, media was gradually changed to 100% BrainPhys. (B) Representative images of jRGECO signal in cultures with BP with and without supplementation at WIC6. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Example traces of jRGECO intensity of cultures in BP with or without supplementation. Grey lines show traces of individual cells and red lines show the average signal in the FOV. (D) Percentage silent cells in a FOV. N numbers of individual experiments and number of FOVs in brackets. B/G/C: 7(37); BP + B/G/C: 7(15); BP -GF: 4(1); BP + B/G/NT3: 7(2); BP + B/G/C + B27: 4(24); BP + B/G/NT3 + B27: 3(18). (E) The mean frequency of calcium events of individual neurons in a FOV. B/G/C: 7(38); BP + B/G/C: 7(39); BP -GF: 4(21); BP + B/G/NT3: 7(39); BP + B/G/C + B27: 4(24); BP + B/G/NT3 + B27: 3(18). (F) The mean frequency of network bursts in a FOV. (G) Percentage of synchronicity, defined by the percentage cells active at the same time. Bar plots represent the mean ± SEM. Each dot represents an a FOV. Kruskal-Wallis H test with Dunn’s correction: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. ns = non-significant, P > 0.05.

At WIC6, neurons cultured in BP with B/G/C supplementation showed more inactive cells compared to neurons in NBM with B/G/C (Figure S3A), and cultures in BP without supplementation showed no activity bursts (Fig. 4B and C, 3SA). Adding B27 to BP with B/G/C, significantly reduced the percentage of inactive neurons, but had no effect in BP with B/G/NT3 (Fig. 4D, 3SA). BP without GFs or supplemented only with B/G/NT3 led to substantial neuronal death (Fig. 4D, S3B). When both B27 and GFs (either B/G/C or B/G/NT3) were added, cultures in BP exhibited cell activity similar to NBM with GFs (Fig. 4E). However, full restoration of network activity and synchronicity was only observed in BP cultures with B/G/C and B27, comparable to NBM with B/G/C (Fig. 4F, G, S3A). This suggests that BP medium requires B27 and specific GFs to maintain optimal neuronal survival and activity.

Given that BP supports neurophysiological activity more than NBM35, we hypothesized that increased spontaneous activity might lead to excitotoxity and cell loss40. To test this, we applied tetrodotoxin (TTX), a voltage-gated sodium channel blocker41. TTX had no adverse effect on neuronal survival in NBM plus B/G/C cultures, but failed to prevent cell death in BP cultures (Figure S3C). To assess the generalizability of these findings, we repeated the experiments in an independent iPSC-line (Kolf2.1 J). In BP, Kolf2.1 J-derived neurons supplemented with B/G/C or B/G/NT3, showed massive cell death or were completely silent at WIC6. In contrast, BP cultures supplemented with B27 and GFs survived, though their network activity remained significantly lower compared to NBM with B/G/C (Figure S3D-G).

Taken together, these results indicate that while BP medium supports spontaneous neuronal activity, it also increases vulnerability of NGN2-neurons if not supplemented. Moreover, when supplemented with B27 and GFs, BP does not enhance network activity beyond what is observed in NBM.

Discussion

In this study, we addressed the effect of key GFs commonly used in neuronal differentiation protocols on the survival, morphology and functional properties of NGN2-induced human neurons. Our findings show that BDNF and GDNF alone are sufficient to maintain neuronal survival, morphology and synapse numbers, with BDNF alone also supporting DCV numbers (Figs. 1 and 2). However, neither factor alone supported SV abundance or robust network activity, which required supplementation with multiple GFs. Notably, combining either BDNF or GDNF with CNTF was sufficient to maintain network activity (Fig. 3). Moreover, the network activity of cultures in BP medium was similar to those in NBM when supplemented with BDNF/GDNF/CNTF and B27 (Fig. 4). These findings highlight the importance of selecting appropriate GF combinations and culture conditions to ensure reliability and physiological relevance when modeling human neuronal functions in vitro.

BDNF or GDNF alone support neuronal survival and morphology

The absence of GFs markedly reduced the number of neurons, that we use as a proxy for neuronal survival, and produced smaller, less complex neurons. In contrast, supplementation with either BDNF or GDNF alone was sufficient to sustain survival and support dendritic length and complexity at levels comparable to supplementation with multiple GFs. In addition, we observed a trend towards a decrease of the number of neurons over time in cultures with GDNF alone, or BDNF/GDNF/NT3. Moreover, while dendrite length and complexity were comparable between BDNF/GDNF/CNTF and BDNF/GDNF/NT3 conditions, the soma size of neurons cultured in BDNF/GDNF/NT3 was smaller, indicating that the lack of BDNF and/or CNTF negatively affect neuronal survival and size to an extent. Inclusion of apoptosis markers, such as caspase-3, could offer further insights into the direct effect on neuronal survivability. For now, our findings align with previous studies, showing that BDNF promotes neuronal survival and dendritic outgrowth in vitro13. Although CNTF has previously been described to be neuroprotective upon injury31,32,33, we find that CNTF alone is not sufficient to maintain neuronal survival or morphology comparable to cultures with multiple GFs. These findings suggest that BDNF plays a central role in supporting neuronal health in vitro, whereas CNTF may depend on synergistic interactions with additional trophic factors to exert comparable effects. During our submission process, Dimitrov et al. (2025) reported that combining BDNF/GDNF/CNTF with neurturin (NRTN), a GDNF-family neurotrophic factor, further enhanced neuronal survival, soma size, and function. Using a proteomics-based approach, they identified neurotrophic receptors and optimized neuronal differentiation by supplementing with their corresponding ligands42. Overall, their findings are consistent with our data.

BDNF alone is sufficient to maintain DCV- and synapse numbers

We found that BDNF was the only GF that maintained DCV numbers at levels comparable to supplementation with multiple GFs. By contrast, cultures treated with BDNF/GDNF/NT3 showed reduced DCV numbers compared to those treated with BDNF/GDNF/CNTF, suggesting that NT3 may negatively influence DCV biogenesis. Previous studies have shown that high levels of NT3 can trigger receptor internalization43 and, when co-expressed with BDNF, shift secretion from constitutive to regulated release44. The implications for DCV biogenesis however remain unclear. The absence of GFs decreased DCV density but had no effect on DCV content, indicating that GF supplementation affects DCV biogenesis and/or their lifetime rather than cargo loading. Based on this, we suggest that NT3 supplementation might be omitted, especially for DCV studies, whereas BDNF should be included, when studying DCV biology in NGN2-neurons.

Furthermore, cultures without GFs or with CNTF alone showed fewer Syp1 puncta, indicative of reduced presynaptic structures. However, Syp1 puncta density was unchanged, suggesting that the lower presynaptic structures likely reflect decreased neuronal length rather than impaired synaptogenesis. Syp1 intensity however was reduced in all conditions except BDNF/GDNF/NT3 compared to BDNF/GDNF/CNTF, indicating that multiple GFs are required to sustain SV abundance.

BDNF, GDNF or CNTF alone are not sufficient to maintain neuronal activity

We show that cultures supplemented with only a single GF (BDNF, GDNF or CNTF) have reduced network bursting and a higher percentage of silent neurons. This indicates that individual GFs are insufficient to sustain functional network activity at levels comparable to supplementation with multiple GFs. However, it may also be possible that the concentrations of single GFs were too low to compensate for the absence of additional trophic support, as we did not increase their levels in isolation. Interestingly, the combination of BDNF and GDNF, while sufficient for neuronal survival and morphology individually, resulted in lower network activity compared to cultures with BDNF/GDNF/CNTF. This indicates that CNTF is required to maintain network activity. This could be explained by previous studies showing that CNTF indirectly increases calcium influx in neurons by stimulating astrocytes45,46. Based on this, we speculate that the absence of CNTF may affect astrocyte function, leading to decreased calcium transients in neurons. Indeed, cultures supplemented with CNTF together with either BDNF or GDNF exhibited network activity similar to BDNF/GDNF/CNTF, reinforcing the idea that CNTF plays a specific, possibly glia-mediated, role in sustaining spontaneous neuronal network activity. Furthermore, we showed that cultures in BDNF/GDNF/CNTF and BDNF/GDNF/NT3 had similar network activity, despite BDNF/GDNF/NT3 cultures tending to have less neurons at WIC6 (Fig. 1), smaller somas (Figure S1), and fewer DCVs (Fig. 2). These findings indicate that CNTF and NT3, when combined with BDNF and GDNF, are functionally redundant for sustaining network activity, but not for all cellular properties and should therefore carefully be selected depending on the research question. Our results highlight that minimal GF combinations are sufficient to support neuronal functionality, with CNTF being indispensable. We therefore propose that CNTF should be included together with either BDNF or GDNF, depending on the specific research question.

BrainPhys and neurobasal supplemented with B27 and GFs equally support spontaneous network activity

BP medium has been developed to better mimic the ion composition of cerebrospinal fluid35. Nonetheless, we found that spontaneous network activity in BP was comparable to NBM, provided that both were supplemented with BDNF/GDNF/CNTF and B27. In the absence of these supplements, cultures in BP showed extensive cell death and lacked detectable network activity across multiple male iPSC-derived neuronal lines. Female iPSC lines have not been included in this study, further work could explore whether their inclusion might influence the findings. Our findings emphasize that even in optimized physiological media like BP, adequate trophic supplementation remains critical for neuronal survival and functional network activity in human iPSC-derived neurons.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive examination of the impact of BDNF, GDNF, CNTF and NT3 on the survival, morphology, and functional properties of human iPSC-derived NGN2-neurons. While individual GFs contributed selectivity to neuronal survival, morphology, or function, our results demonstrate that optimal structural and functional maturation requires combining CNTF with either BDNF or GDNF. Finally, our findings indicate that NBM and BP, when supplemented appropriately, were equally effective in maintaining spontaneous network activity. Therefore, media selection may be based by considerations other than neuronal functionality. These insights offer practical guidance for optimizing differentiation protocols, thereby enhancing the reliability and translational value of NGN2-neuron–based in vitro models for disease research and drug discovery.

Materials and methods

iPSC origin and culture

Unless stated otherwise, the BiONi010-C-10 male iPSC line (purchased from EBiSC, RRID: CVCL_RM84) was used for all experiments in this study. KOLF2.1 J male iPSCs were used in Supplementary Fig. 3 (purchased from the Jackson laboratory JAX, JiPSC001000, RRID: CVCL_B5P3). All iPSCs were maintained in E8 medium with 0.1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S, Fisher Scientific) on Geltrex-coated plates (VWR).

Neuronal induction

BIONi010-C-10 and KOLF2.1 J iPSCs were driven towards a neuronal fate by Tet-inducible expression of neurogenin-2 (NGN2) using a PiggyBac transposon (PB-TO-hNGN2) system for delivery (kind gift from Dr. Hebao Yuan, National Institutes of Health/NINDS Bethesda, United States). Neuronal differentiation was started by dissociating iPSCs with accutase (Merck Millipore) and transferring them to Geltrex coated 100 mm dishes (Sarstedt) in DMEM/F12 + GlutaMAX™ (Gibco) supplemented with N2 supplement (Stemcell Technologies), 0.1% P/S, 200 mM GlutaMax (Life Tech), 1.5% D-Glucose (20%, Gibco), doxycycline hyclat (dox; 2 µg/ml, Sigma Aldrich), 5 µM ROCK-inhibitor (RI; Y-27632, Tebubio), as well as the SMAD inhibitors LDN-193,189 (100 nM; Stemgent) and SB431542 (10 µM; Tocris), and the WNT inhibitor XAV939 (2 µM; Stemgent). The next day, cells were refreshed with the same medium with puromycin (2 µg/ml; Sanbio), but without RI. On day 3, cells were refreshed with the same medium and 10 µM FUDR (Sigma Aldrich). On day 4, the neurons were plated in neurobasal medium (NBM; Gibco) supplemented with 200 mM Glutamax (Life Tech), 20% Dextrose (Life Tech), non-essential amino acids (NEAA; 1:200; LifeTech), B27 (1:50; LifeTech), 0.1% P/S (LifeTech), 0.5% Fetal bovine serum (LifeTech) and growth factors. NBM was either supplemented with BDNF, GDNF and CNTF (all 10 ng/ml, Stemcell Technologies); only BDNF, GDNF or CNTF; BDNF, GDNF and NT3 (10 ng/ml, Tebubio, Peprotech); or no growth factors.

For immunostainings, the cells were plated at a density of 2k cells per 18 mm coverslip. Coverslips contained glial micro islands as described previously5. Single neurons will attach to the glia island and form synapses with themselves (autapses)47. Coverslips were coated with agarose (Type II-A; Sigma, A9918) and stamped with a mixture of 0.1 mg/ml poly-D lysine (Sigma, P6407), 0.7 mg/ml rat tail collagen (BD Biosciences, 354236), and 10 mM acetic acid (Sigma, 45731) using a custom-made stamp. Rat glia were plated at a density of 8k per coverslip. For calcium imaging, cells were plated at a density of 15k per well on glia in a 96-well plate (continental). Neurons were maintained at 37◦C and 5% CO2. Half of NBM was refreshed once weekly for autaptic cultures and twice weekly for continental cultures. For the TTX experiments, 1 µM TTX (Hello Bio, HB1035) per well was added to the culture media during maintenance twice weekly. Experiments were performed on days 14 to 16 (WIC2), 38 to 30 (WIC4) and 42 to 44 (WIC6) after the start of differentiation.

Immunocytochemistry

Neurons were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Merck) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) for 20 min at room temperature (RT). Cells were immediately immunostained or kept in PBS at 4 °C. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min and blocked with 2% normal goat serum (Fisher Emergo) in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at RT. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at RT, or overnight at 4 °C. Primary antibodies used were: polyclonal MAP2 (1:500, Abcam), polyclonal Chromogranin A (1:500, SySy), and polyclonal Synaptophysin 1 (1:500, SySy). Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500, Invitrogen) were incubated for 1–2 h at RT. Coverslips were mounted in Mowiol (Sigma-Aldrich). Images were acquired on an A1R Nikon confocal microscope with LU4A laser unit (40x objective; NA 1.3) and NIS elements software (version 4.60, Nikon). For each cell, 5 planes were acquired in a z-stack with increments of 0.5 μm. Z-stacks were collapsed to maximal projections for image analysis using ImageJ Fiji. A NIKON Ti-Eclipse microscope, an EMCCD camera (Andor DU-897), in brightfield, x20 air (NA = 0.75) and controlled by NisElements AR 5.30.06 software was used to manually count the number of neurons per coverslip.

Neuronal morphology analysis and the quantification of endogenous ChgA and Syp1 puncta were performed using SynD software (version 491)48,49, running in MATLAB (MathWorks). A dendrite mask was created using MAP2 immunostaining, form which single pixel images were obtained. The distance between neighboring pixels within the mask were summed together to determine the dendritic length. Sholl analysis was preformed to determine the degree of dendritic branching. Circles with increasing radius were automatically drawn from the soma outward. The number of times dendrites intersected these circles served as a quantitative measure of dendritic branching48. Furthermore, all ChgA and Syp1 puncta were divided by the mode of the first quartile of the puncta intensity values to estimate the total number of DCVs and SVs, respectively. Based on this, the total number of DCVs or SVs per neuron was quantified. The intensity values of ChgA and Syp1 are normalized to the BDNF/GDNF/CNTF condition per independent week.

Calcium imaging

Neurons were infected with a lentivirus expressing the calcium indicator jRGECO under the synapsin promoter, 7 days before the first recording. Images of spontaneous activity were acquired with a NIKON Ti-Eclipse microscope, an EMCCD camera (Andor DU-897), appropriate filter sets, x20 air (NA = 0.75) and controlled by NisElements AR 5.30.06 software. Exposure time was set to 125 ms, images were acquired at 8 Hz frame rate, time of acquisition was 2 min. DIC images were taken for ROI detection. The analysis was performed with an in-house pipeline available in GitHub at https://git.vu.nl/public-neurosciences-fga/matlab-apps/scaspa. ROIs were manually selected. Thresholding for peak detection was performed using the median absolute deviation.

Statistical analyses

Statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.2.3). Normal distributions of all data were assessed with Shapiro-Wilk normality tests. One-way ANOVA was used in case of normal distributed data or Kruskal Wallis test for non-parametric data, followed by Dunnett’s or Dunn’s multiple comparisons test to compare conditions, respectively. Two-way ANOVA was performed to assess the interaction between factors, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. The conditions were compared to the BDNF/GDNF/CNTF condition. Data is represented as bar or line plots showing the mean and SEM. For immunocytochemistry data, N numbers represent the number of independent experiments and single neuron observations in brackets, unless stated otherwise. For calcium imaging data, N numbers represent the number of independent experiments and field of views (FOV) in brackets. Dots in all graphs indicate single neuron observations, the number of coverslips or FOV. All statistical analyses were performed on single neuron observations or FOV observations, unless stated otherwise.

Data availability

All data and constructs used will be made available upon reasonable request. The calcium imaging analysis pipeline is available in GitHub at https://git.vu.nl/public-neurosciences-fga/matlab-apps/scaspa.

Abbreviations

- BDNF:

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BP:

-

BrainPhys

- ChgA:

-

Chromogranin A

- CNTF:

-

Ciliary neurotrophic factor

- DCV:

-

Dense core vesicle

- GDNF:

-

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- GF:

-

Growthfactor

- iPSC:

-

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- NBM:

-

Neurobasal medium

- NGN2:

-

Neurogenin-2

- NT3:

-

Neurotrophin-3

- SV:

-

Synaptic vesicle

- Syp1:

-

Synaptophysin-1

- TTX:

-

Tetrodotoxin

- WIC:

-

Week(s) in culture

References

Hulme, A. J., Maksour, S., Glover, M. S. C., Miellet, S. & Dottori, M. Making neurons, made easy: the use of Neurogenin-2 in neuronal differentiation. Stem Cell. Rep. 17, 14–34 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Rapid Single-Step induction of functional neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Neuron 78, 785–798 (2013).

Jacobson, M. D., Weil, M. & Raff, M. C. Program. Cell. Death Rev. Anim. Dev. (1997).

Reichardt, L. F. Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 361, 1545–1564 (2006).

Meijer, M. et al. A Single-Cell model for synaptic transmission and plasticity in human iPSC-Derived neurons. Cell. Rep. 27, 2199–2211e6 (2019).

Nehme, R. et al. Combining NGN2 programming with developmental patterning generates human excitatory neurons with NMDAR-Mediated synaptic transmission. Cell. Rep. 23, 2509–2523 (2018).

Shan, X. et al. Fully defined NGN2 neuron protocol reveals diverse signatures of neuronal maturation. Cell Rep. Methods. 4, 100858 (2024).

Barde, Y. A., Edgar, D. & Thoenen, H. Purification of a new neurotrophic factor from mammalian brain. https://www.embopress.org/doi/epdf/ (1982). https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01207.x

Ortega-Gasco, A. et al. BDNF overexpression enhances neuronal activity and axonal growth in human iPSC-Derived neural cultures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 26, 7262 (2025).

Shelly, M., Cancedda, L., Heilshorn, S., Sumbre, G. & Poo, M. LKB1/STRAD promotes axon initiation during neuronal polarization. Cell 129, 565–577 (2007).

Wirth, M. J., Brün, A., Grabert, J., Patz, S. & Wahle, P. ccelerated dendritic development of rat cortical pyramidal cells and interneurons after biolistic transfection with BDNF and NT4/5. Development 130, 5827–5838 (2003).

Dieni, S. et al. BDNF and its pro-peptide are stored in presynaptic dense core vesicles in brain neurons. J. Cell. Biol. 196, 775–788 (2012).

Shetty, A. K. & Turner, D. A. In vitro survival and differentiation of neurons derived from epidermal growth factor-responsive postnatal hippocampal stem cells: inducing effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neurobiol. 35, 395–425 (1998).

Ahmed, S., Reynolds, B. & Weiss, S. BDNF enhances the differentiation but not the survival of CNS stem cell- derived neuronal precursors. J. Neurosci. 15, 5765–5778 (1995).

Park, H. & Poo, M. Neurotrophin regulation of neural circuit development and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 7–23 (2013).

Tanaka, J. et al. Protein synthesis and Neurotrophin-Dependent structural plasticity of single dendritic spines. Science 319, 1683–1687 (2008).

Duarte Azevedo, M., Sander, S. & Tenenbaum, L. G. D. N. F. A Neuron-Derived factor upregulated in glial cells during disease. J. Clin. Med. 9, 456 (2020).

Bresjanac, M. & Antauer, G. Reactive astrocytes of the quinolinic Acid-Lesioned rat striatum express GFRα1 as well as GDNF in vivo. Exp. Neurol. 164, 53–59 (2000).

Marco, S. et al. Excitatory amino acids differentially regulate the expression of GDNF, Neurturin, and their receptors in the adult rat striatum. Exp. Neurol. 174, 243–252 (2002).

Lin, L. F. H., Doherty, D. H., Lile, J. D., Bektesh, S. & Collins, F. GDNF: a glial cell Line-Derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science 260, 1130–1132 (1993).

Airaksinen, M. S. & Saarma, M. The GDNF family: Signalling, biological functions and therapeutic value. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 383–394 (2002).

Lonka-Nevalaita, L. et al. Characterization of the intracellular Localization, Processing, and secretion of two glial cell Line-Derived neurotrophic factor splice isoforms. J. Neurosci. 30, 11403–11413 (2010).

Ledda, F., Paratcha, G., Sandoval-Guzmán, T. & Ibáñez, C. F. GDNF and GFRα1 promote formation of neuronal synapses by ligand-induced cell adhesion. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 293–300 (2007).

Van Berkel, A. A. et al. Reduced MUNC18-1 Levels, synaptic proteome Changes, and altered network activity in STXBP1-Related disorder patient neurons. Biol. Psychiatry Glob Open. Sci. 4, 284–298 (2024).

Öttl, M., Toonen, R. F. & Verhage, M. Reduced synaptic depression in human neurons carrying homozygous disease-causing STXBP1 variant L446F. Hum. Mol. Genet. 33, 991–1000 (2024).

Vicario-Abejón, C., Collin, C., McKay, R. D. G. & Segal, M. Neurotrophins induce formation of functional excitatory and inhibitory synapses between cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 18, 7256–7271 (1998).

Ip, N. Y. The neurotrophins and neuropoietic cytokines: two families of growth factors acting on neural and hematopoietic cells. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 840, 97–106 (1998).

Ip, N. Y. & Yancopoulos, G. D. The neurotrophins and CNTF: two families of collaborative neurotrophic factors. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 491–515 (1996).

Hughes, S. M., Lillien, L. E., Raff, M. C., Rohrer, H. & Sendtner, M. Ciliary neurotrophic factor induces type-2 astrocyte differentiation in culture. Nature 335, 70–73 (1988).

Escartin, C. et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor activates Astrocytes, redistributes their glutamate transporters GLAST and GLT-1 to raft Microdomains, and improves glutamate handling in vivo. J. Neurosci. 26, 5978–5989 (2006).

Kang, S. S., Keasey, M. P., Cai, J. & Hagg, T. Loss of Neuron-Astroglial interaction rapidly induces protective CNTF expression after stroke in mice. J. Neurosci. 32, 9277–9287 (2012).

Pernet, V. et al. Long-distance axonal regeneration induced by CNTF gene transfer is impaired by axonal misguidance in the injured adult optic nerve. Neurobiol. Dis. 51, 202–213 (2013).

Pöyhönen, S., Er, S., Domanskyi, A. & Airavaara, M. Effects of neurotrophic factors in glial cells in the central nervous system: expression and properties in neurodegeneration and injury. Front Physiol. 10, 486, (2019).

Brewer, G. J., Torricelli, J. R., Evege, E. K. & Price, P. J. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J. Neurosci. Res. 35, 567–576 (1993).

Bardy, C. et al. Neuronal medium that supports basic synaptic functions and activity of human neurons in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, E2725–E2734 (2015).

Persoon, C. M. et al. Pool size estimations for dense-core vesicles in mammalian CNS neurons. EMBO J. 37, e99672 (2018).

Alsina, B., Vu, T. & Cohen-Cory, S. Visualizing synapse formation in arborizing optic axons in vivo: dynamics and modulation by BDNF. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1093–1101 (2001).

Vicario-Abejón, C., Owens, D., McKay, R. & Segal, M. Role of neurotrophins in central synapse formation and stabilization. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 965–974 (2002).

Dana, H. et al. Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity. eLife 5, e12727 (2016).

Wang, Y. & Qin, Z. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of excitotoxic neuronal death. Apoptosis 15, 1382–1402 (2010).

Narahashi, T., Moore, J. W. & Scott, W. R. Tetrodotoxin blockage of sodium conductance increase in Lobster giant axons. J. Gen. Physiol. 47, 965–974 (1964).

Dimitrov, D. et al. Proteomics-based receptor-ligand matching enhances differentiation maturity of human-stem-cell-derived neurons. Stem Cell. Rep. 102604 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2025.102604 (2025).

Han, K. A. et al. Neurotrophin-3 regulates synapse development by modulating TrkC-PTPσ synaptic adhesion and intracellular signaling pathways. J. Neurosci. 36, 4816–4831 (2016).

Farhadi, H. F. et al. Neurotrophin-3 sorts to the constitutive secretory pathway of hippocampal neurons and is diverted to the regulated secretory pathway by coexpression with Brain-Derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neurosci. 20, 4059–4068 (2000).

Sun, M., Liu, H., Min, S., Wang, H. & Wang, X. Ciliary neurotrophic factor-treated astrocyte-conditioned medium increases the intracellular free calcium concentration in rat cortical neurons. Biomed. Rep. 4, 417–420 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Ciliary neurotrophic Factor-treated astrocyte conditioned medium regulates the L-type calcium channel activity in rat cortical neurons. Neurochem Res. 33, 826–832 (2008).

Bekkers, J. M. & Stevens, C. F. Excitatory and inhibitory autaptic currents in isolated hippocampal neurons maintained in cell culture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 88, 7834–7838 (1991).

Schmitz, S. K. et al. Automated analysis of neuronal morphology, synapse number and synaptic recruitment. J. Neurosci. Methods. 195, 185–193 (2011).

van de Bospoort, R. et al. Munc13 controls the location and efficiency of dense-core vesicle release in neurons. J. Cell. Biol. 199, 883–891 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Judith Huijgen and Solange Lopes Cardozo for iPSCs maintenance, Lennert Koomen for maintaining and performing calcium imaging of the Kolf2.1J neurons, Robbert Zalm and Ingrid Saarloos for cloning and producing viral particles, Desiree Schut and Lisa Laan for astrocyte culture, and Jurjen Broeke and Ana Carreras Mascaro for assistance with calcium imaging and data analysis.

Funding

This work is supported by ZONMW project NewTDec (NWA 91216064) and ZonMW PSIDER project Brainmodel (40-46800-98-010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Abramian: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation methodology, visualization, and writing – original draft, review and editing. A. Damaskou: formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and writing – original draft. R.F. Toonen: supervision, and writing – review and editing. M. Verhage: Supervision, funding acquisition, and writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abramian, A., Damaskou, A., Toonen, R.F. et al. Growth factor supplementation modulates survival, morphology, and network activity of neurogenin-2 induced human neurons. Sci Rep 16, 2118 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31868-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31868-4