Abstract

In English-medium postgraduate classrooms, particularly within MSc/MA TESOL programs in the UK, many Chinese students hesitate to pose questions despite possessing advanced English proficiency. This qualitative study aims to address three critical gaps in the literature: (1) the underexploration of postgraduate learners’ affective experiences in immersive English-speaking contexts, (2) the neglect of routine classroom interactions such as question-posing compared to formal speaking tasks, and (3) the limited understanding of how cultural and educational traditions shape anxiety in graduate-level TESOL programs. Drawing on semi-structured interviews with five Chinese postgraduates, the research investigates the psychological, cultural, and contextual dimensions of question-posing anxiety. Findings highlight key contributing factors—including linguistic insecurity, fear of negative evaluation, perceived inadequacy of questions, cross-cultural classroom norms, and the legacy of prior educational socialization—manifesting in both cognitive and physiological symptoms. Students also reported employing adaptive strategies such as self-talk, peer rehearsal, and deliberate body language to navigate these challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The globalization of higher education has led to a dramatic increase in the number of Chinese students pursuing graduate studies in British universities, with this demographic now representing the largest cohort of international learners in the UK. While this trend reflects the growing prestige of Western academia and the aspirations of Chinese students to engage with global educational systems, it also underscores a critical pedagogical challenge: despite meeting institutional English language requirements, many of these students encounter significant difficulties in adapting to the interactive demands of Anglophone academic culture. Research consistently demonstrates that Chinese learners experience disproportionately high levels of anxiety when required to use English in classroom settings, particularly in spontaneous oral interactions such as questioning, discussion, and seminar participation1,2. This phenomenon persists even among advanced learners enrolled in linguistically intensive programs like MSc/MA TESOL, where communicative competence is both a learning outcome and a prerequisite for academic success.

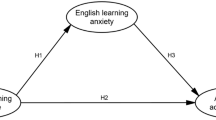

The psychological and cognitive burdens imposed by second language (L2) communication have been well-documented in the literature on foreign language anxiety (FLA), a construct first systematically theorized by Horwitz et al. (1986) to describe the “distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning” (p. 128)3. Empirical studies across diverse linguistic and educational contexts have established FLA as one of the most significant affective variables hindering L2 acquisition, with meta-analyses indicating robust negative correlations between anxiety and oral proficiency4. The manifestation of this anxiety is particularly acute in situations requiring real-time language production, such as answering instructor queries, volunteering responses, or—as this study focuses on—posing questions to clarify or challenge academic content5. For Chinese learners, these challenges are often compounded by sociocultural factors, including educational traditions that prioritize receptive over productive skills and Confucian values emphasizing deference to authority6. Consequently, even highly proficient students may avoid verbal engagement to prevent potential loss of face, creating a paradox where their silence contradicts both pedagogical expectations and their own intellectual curiosity.

While the broader literature on FLA is extensive, several critical gaps necessitate further investigation. First, the majority of studies have examined undergraduate populations or EFL contexts (e.g., language classrooms in non-English-speaking countries), leaving the experiences of postgraduate learners in immersive ESL settings—where academic survival depends on daily L2 use—relatively underexplored7. Second, research has disproportionately focused on anxiety in formal speaking tasks (e.g., presentations, exams) rather than routine classroom interactions like question-posing, despite evidence that the latter plays a pivotal role in cognitive engagement and conceptual mastery8. Third, while cultural comparisons often position Chinese learners as more anxiety-prone than their Western counterparts2, few studies have empirically investigated how this population negotiates anxiety within the specific demands of graduate-level TESOL programs, where metacognitive awareness of language pedagogy might uniquely influence their affective responses.

This study addresses critical gaps in the literature on foreign language anxiety (FLA) by examining how it manifests in the everyday act of question-posing within postgraduate TESOL classrooms. Unlike much of the existing research, which focuses on undergraduate learners, EFL settings, or formal speaking tasks such as presentations, this study explores the routine but pivotal interaction of asking questions in immersive UK postgraduate programs. The research pursues three interconnected aims:

-

1.

To identify the psychological, sociocultural, and educational factors that contribute to Chinese postgraduate students’ anxiety when posing questions in UK TESOL classrooms.

-

2.

To investigate how this anxiety shapes their classroom participation, identity negotiation, and overall learning experience.

-

3.

To examine the strategies students adopt to cope with or mitigate question-posing anxiety.

These aims are reflected in the following research questions (1) What factors—psychological, cultural, and situational—contribute to Chinese MSc/MA TESOL students’ anxiety when posing questions in class? (2) How does this anxiety influence their classroom participation and broader academic experience? (3) What coping strategies do students develop to manage or reduce their question-posing anxiety? The significance of this research lies in its dual contribution. Theoretically, it extends current understandings of FLA by situating it in a postgraduate, intercultural TESOL context and by highlighting the overlooked practice of question-posing as a critical site of anxiety. Practically, it provides actionable insights for UK educators and program designers, offering strategies to foster more inclusive participation, enhance classroom interaction, and better support Chinese postgraduates—the largest cohort of international students in the UK. In doing so, the study bridges the gap between theory and pedagogy, positioning question-posing not merely as a linguistic challenge but as a window into the affective and cultural complexities of international education.

Literature review

Foreign language anxiety

The study of anxiety specifically associated with foreign language began in the second half of the 20th century. In 1973, Brown investigated the role of affective variables in language learning and found that such variables are closely related to people’s success in language learning, with anxiety emerging as a major affective variable. In the subsequent decade, Horwitz et al. (1986) formally proposed the term “foreign language anxiety,” or “FLA” on the basis of situational anxiety theory. For Horwitz et al. (1986), anxiety is a subjective feeling of tension, anxiety and annoyance caused by the autonomic nervous system3.

In learning contexts, this experience may result in a significant degree of pressure being exerted on students in foreign language learning contexts. Horwitz et al. (1986) also argue that there is reason to consider certain experiences of anxiety as instances of a complex psychological phenomenon peculiar to language learning, being an independent compound emotion that integrates self-perception, belief, emotion and behaviour generated by the uniqueness of language learning process. Maclntyre and Gardner (1994) later conceptualised foreign language anxiety as a state of tension and fear specifically related to language use in second language contexts3,9. They argued that it is characterised by feelings of apprehension, unease and tension arising in language-related situations, such as speaking in the target language, participating in language classes, or being evaluated on one’s language proficiency10. Wang and Wan (2001) similarly defined foreign language anxiety nervousness or fear experienced by individuals as a result of a lack of familiarity with and/or confidence in the target language. This definitional tradition was also continued by Li since 20047,11, who conceptualised foreign language anxiety in terms of the psychological tension experienced by language learners when they need to speak a foreign language.

The multidimensional impact of anxiety in second language acquisition

Anxiety in second language acquisition (SLA) operates as a complex affective filter, exerting both psychological and physiological influences that disrupt learners’ communicative engagement12,13,14. Psychologically, it manifests as a debilitating cycle of cognitive interference, where learners’ preoccupation with potential errors overshadows their linguistic performance3. This cognitive burden often leads to avoidance behaviors, particularly in question-posing scenarios, as students internalize fears of appearing incompetent15. The somatic dimension of anxiety further compounds these challenges, triggering autonomic responses such as tachycardia, vocal tremors, and hyperhidrosis—physiological reactions that inadvertently reinforce self-perceptions of inadequacy16. Crucially, this bidirectional relationship between mind and body creates a feedback loop: physiological symptoms validate learners’ psychological apprehensions, while cognitive distress amplifies bodily stress responses17.

The unique nature of language anxiety distinguishes it from general academic anxiety. Unlike subject-specific apprehensions (e.g., mathematics anxiety), foreign language anxiety (FLA) permeates both the process and product of learning, as the target language simultaneously serves as the medium and object of instruction18. This duality explains why even proficient learners—particularly those from collectivist educational backgrounds like China—may experience disproportionate distress when required to vocalize questions spontaneously5. The classroom consequently transforms into an arena of perceived linguistic surveillance, where every utterance undergoes imagined scrutiny19.

Determinants of question-posing anxiety in L2 classrooms

The reluctance to initiate questions among language learners stems from an interplay of dispositional, pedagogical, and sociocultural factors. At the individual level, trait anxiety predisposes certain learners to interpret question-posing as a high-stakes performance rather than a collaborative learning opportunity20. This tendency intensifies among perfectionistic students, whose dichotomous views of language accuracy lead to catastrophic appraisals of minor errors21. The fear of negative evaluation (FNE) operates as a particularly potent inhibitor, with collectivist-oriented learners often prioritizing face preservation over conceptual clarification22.

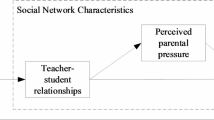

Instructors play a paradoxical role in either mitigating or exacerbating these anxieties. While supportive teaching behaviors—such as extended wait time and formative feedback—can scaffold learners’ question-formulation confidence, abrupt corrections or implicit impatience reinforce perceptions of linguistic vulnerability23. The power asymmetry inherent in teacher-student dynamics further complicates this interaction, as learners from hierarchical educational traditions may perceive questioning as transgressive rather than participatory24. Competitive classroom ecologies introduce additional barriers. In environments where participation is implicitly graded or peer comparisons are salient, students often self-silence to avoid exposing relative weaknesse25. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in Western academic settings that valorize extroverted participation styles, disadvantaging introverted learners whose cultural frameworks privilege reflective listening26.

Adaptive strategies for navigating questioning anxiety

Learners draw on both intrapersonal and interpersonal strategies to cope with the specific anxiety that arises when formulating and asking questions. Metacognitive techniques—particularly cognitive reframing—help students view their hesitation not as a personal flaw but as a typical part of developing communicative competence27. This perspective echoes Bandura’s (1997) account of self-efficacy: small, successful attempts in low-pressure questioning moments can gradually strengthen learners’ confidence and reduce avoidance tendencies28.

Interpersonal strategies are equally influential in question-posing contexts. Peer rehearsal groups or informal learning alliances often serve as “safe spaces” where students can trial their questions before speaking publicly, lowering the linguistic and social risks involved29. Such practices reflect Vygotskian notions of distributed cognition, where collaborative meaning-making eases individual affective strain. Even seemingly simple behaviours—pausing briefly to collect one’s thoughts or using quick notes to structure a question—function as transitional supports that allow learners to manage anxiety while staying engaged30.

Recent work also points to the potential of mindfulness-based techniques. Controlled breathing or grounding exercises can temper the physiological responses that typically escalate during classroom questioning, helping learners shift attention from producing a “perfect” question to conveying their intended meaning31. This process-oriented mindset is particularly useful in spontaneous question-posing, where communicative intent matters more than linguistic polish.

Although these strands of research have enriched our understanding of FLA, they rarely address the unique pressures associated with initiating questions in academic settings. Studies tend to focus on more formal speaking tasks—presentations, seminars, or oral assessments32,33—while treating questioning as a minor indicator of participation. Yet question-posing involves additional layers of judgement: assessing the relevance and timing of a question, anticipating how it may be received, and navigating classroom hierarchies or intercultural norms. These demands often make questioning more anxiety-provoking than other routine interactions. The limited research that touches on questioning usually frames it as a by-product of participation rather than as a communicative act with its own psychological and pedagogical weight34. As a result, current FLA scholarship underrepresents how anxiety shapes learners’ willingness to question, and how questioning functions as an epistemic practice central to academic engagement. Addressing this gap, the present study foregrounds question-posing as a distinct site of anxiety within internationalized higher education.

Research methodology

This study employed a qualitative phenomenological approach to investigate the lived experiences of Chinese TESOL postgraduate students regarding question-posing anxiety in UK university classrooms. The methodology was designed to capture the nuanced psychological and sociocultural dimensions of this phenomenon through in-depth exploration of participants’ subjective experiences.

Research design and rationale

The study adopted a phenomenological research design, which is particularly suited to examining how individuals make meaning of their lived experiences35,36,37,38,39. This approach aligns with the study’s objectives of understanding: The essential structures of question-posing anxiety experiences; The contextual factors shaping these experiences; The coping mechanisms developed by participants. As illustrated in Table 1, the phenomenological approach offers distinct advantages for investigating affective dimensions of second language acquisition compared to alternative methodologies.

Participant selection and characteristics

Participants were recruited through purposeful sampling to ensure information-rich cases40. The final cohort comprised five Chinese nationals enrolled in MSc/MA TESOL programs at UK universities, meeting the following inclusion criteria: Native Mandarin speakers with IELTS 6.5 + or equivalent; Minimum six months’ study experience in UK higher education; Self-reported experience of classroom question-posing anxiety. Conducting multiple, in-depth, semi-structured interviews with five participants generated a substantial amount of rich, first-hand narrative data. This approach allows the researcher to move beyond superficial phenomena and examine the unique causes, specific contexts, and nuanced coping strategies associated with each participant’s experience of anxiety. A larger sample size would inevitably compromise the depth of the interviews and the granularity of data analysis, thereby undermining the study’s core objective of elucidating how individuals construct their experiences of anxiety. Although the sample size is small, the composition of the five participants was deliberately designed to incorporate sufficient diversity to capture key variables that may influence the experience of anxiety, thereby significantly enhancing the informational density and analytical insight of the study. This heterogeneity is reflected in the following dimensions: First, gender and age distribution: The sample includes participants of different genders (three women and two men) and covers a representative age range (23–25 years). This allows the study to preliminarily explore how gender may interact with the experience of anxiety. Second, and most strategically, variation in teaching experience: The sample intentionally includes three participants with teaching experience and two without, forming a natural comparative group. Participants with teaching experience may possess more acute insights into classroom interactions and teacher–student power dynamics due to their professional background. Their anxiety may stem from role conflict—being a teacher placed in a student position—or from higher self-expectations regarding the quality of their questions. In contrast, participants without teaching experience may exhibit anxiety more typical of novice learners, such as unfamiliarity with the academic environment or linguistic insecurity. This contrast offers a valuable perspective for analyzing how prior professional identity moderates’ anxiety—an insight unattainable with a homogeneous sample. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2 to enhance study transparency and replicability (See Appendix 1 for detailed data). Although the sample is small, its composition—varying in gender, prior teaching experience, and academic trajectories—provides sufficient heterogeneity to surface key themes relevant to question-posing anxiety. This diversity allows the study to examine both commonalities and contrasts in experiences, which is valuable for exploratory qualitative research.

Data collection procedures

Phase 1: pilot testing

Three preliminary interviews identified necessary protocol adjustments, particularly regarding question sequencing and rapport-building techniques. The pilot revealed that beginning with general classroom experiences before addressing anxiety-specific questions yielded more naturalistic responses (See Appendix 2 for detailed data).

Phase 2: formal data collection

Semi-structured interviews averaging 25 min were conducted via Zoom in participants’ native Mandarin to optimize conceptual precision and comfort. The interview protocol progressed through three stages: Contextual establishment (Opening with broad questions about general classroom experiences); Phenomenological exploration (Probing specific instances of question-posing anxiety); Reflective closure (Inviting suggestions for pedagogical improvements). All interviews were audio-recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim, with back-translation verification conducted for selected excerpts to ensure conceptual equivalence between Mandarin and English expressions.

Data analysis framework

Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase framework41, adapted for phenomenological inquiry as shown in Table 3. Throughout the analysis, attention was paid to experiential meaning, contextual nuance, and the lifeworld orientation central to phenomenological research.

NVivo 14 software supported the organization of codes and emerging themes. Peer debriefing sessions helped scrutinize interpretive decisions and refine thematic boundaries.

To demonstrate thematic sufficiency, saturation was monitored throughout the analytic process. After the fourth interview, no new meaning units or experiential categories appeared, and subsequent transcripts reinforced the existing thematic structure. This assessment was confirmed during peer debriefing, where an independent reviewer examined the coded excerpts and agreed that additional interviews were unlikely to generate new themes. This combination of iterative comparison, stability across transcripts, and external verification provided reasonable evidence that thematic sufficiency had been reached.

Ethical considerations and study limitations

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Moray House School of Education and Sport Ethics Committee, University of Edinburgh, under reference number EDU-IRB-2023-78. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, specifically the British Educational Research Association (BERA) Ethical Guidelines (2018)42. To ensure ethical compliance42, the following safeguards were implemented:

-

Informed consent: participants were provided with detailed information sheets and signed written consent forms. Their rights to withdraw at any time were clearly communicated and respected throughout the study.

-

Confidentiality: Data were pseudonymized and securely stored on encrypted, password-protected servers accessible only to the research team.

-

Beneficence: Interview protocols included procedures for managing participant distress, including established referral pathways to support services when necessary.

Moreover, this study also acknowledges two primary limitations. First, the small sample size (n = 5) necessarily restricts the generalizability of the findings. The results should therefore be understood as context-specific insights rather than universally representative claims. Nonetheless, the deliberate inclusion of participants with different genders, teaching experience, and stages of adaptation ensures sufficient diversity to generate meaningful patterns for analysis. Second, reliance on self-reported narratives may introduce recall bias, though this is mitigated by the depth and richness of the data collected.

Results and discussion

Manifestations of question-posing anxiety

Cognitive-affective dimensions

Findings

Participants consistently described experiencing profound psychological distress when attempting to ask questions in classroom settings. The data revealed a tripartite anxiety structure comprising. First, Anticipatory Apprehension. Learners reported extensive pre-question deliberation, often abandoning questions due to linguistic self-doubt. As P4 articulated: “I mentally rehearse each word, fearing my phrasing will confuse the professor. The longer I hesitate, the more I question whether my query deserves class time.“. Second, Status Asymmetry Perception. Participants perceived an implicit power differential when addressing instructors, exacerbating communicative anxiety. P2’s account typified this dynamic: “There’s an unspoken hierarchy—my imperfect English addressing his expertise. When he requests clarification, I panic, trapped between academic curiosity and social humiliation.” Third, Meta cognitive Paralysis. Anxiety impaired cognitive processing during questioning attempts. Participants described working memory overload, where anxiety monopolized attentional resources otherwise available for language formulation and comprehension monitoring.

Interpretation

These findings echo Spielberger’s (1983) state-trait anxiety theory, highlighting how anticipation, authority dynamics, and cognitive overload interact to paralyze performance. They extend MacIntyre’s (1995)9 anxiety-avoidance model by showing that anxiety is not only triggered by spontaneous speech but also by the preparatory and evaluative stages of question-posing. This underscores that anxiety operates cyclically: hesitation leads to silence, which in turn reinforces future avoidance. Pedagogically, this suggests that instructors should design structured opportunities for low stakes questioning to disrupt this cycle and help students reframe questioning as collaborative inquiry rather than performance17,43,44.

Somatization of anxiety

Findings

Physiological manifestations provided visible and often disruptive markers of participants’ distress, as summarized in Table 4.

P2’s experience illustrates this psychophysiological interplay, P2, a 24-year-old female MA TESOL student with no prior teaching experience: “My pulse pounds in my ears as I raise my hand. Words that flowed perfectly in my mind emerge fragmented—the harder I try to control my speech, the more my voice betrays me.”

Interpretation

These physiological responses mirror the “freeze” reaction in threat response theory (Schmidt et al., 2008)46, suggesting learners perceive questioning as a high-stakes performance rather than a collaborative learning opportunity. The data underscore the need for three. First, Pre-questioning Scaffolds. Structured “think-pair-share” protocols could mitigate anticipatory anxiety by providing peer rehearsal opportunities. Second, Nonverbal Participation Channels. Implementing backchannel tools (e.g., anonymous digital questioning) may circumvent the physiological barriers identified. Third, Instructor Training. Conscious modeling of discursive vulnerability (e.g., professors verbalizing their own clarification questions) could normalize the questioning process.

Importantly, these findings expand the scope of Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) research. Much of the existing literature has emphasized cognitive and affective dimensions—such as fear of negative evaluation or diminished self-efficacy—while physiological symptoms have been noted but often treated as peripheral or secondary16,37. The present study suggests otherwise: somatization appears to be a central component of the anxiety experience, one that directly undermines cognitive processing and limits linguistic output during question-posing. From this perspective, physiological responses are not incidental but integral to understanding how anxiety operates in L2 classrooms38. Recognizing somatization as a core mechanism challenges deficit views of anxious learners. Rather than evidence of personal weakness, these bodily reactions can be seen as rational responses to perceived communicative risk in intercultural classrooms. This reframing both strengthens the theoretical construct of FLA and underscores the pedagogical need to address physical as well as psychological manifestations of anxiety. Practical strategies may include structured pre-questioning scaffolds (e.g., “think-pair-share” activities38,39), the use of alternative participation channels (such as anonymous digital platforms), and deliberate instructor modeling of discursive vulnerability (e.g., openly verbalizing their own clarification questions). Together, these measures can normalize questioning, reduce the physiological burden of participation, and support learners in managing the embodied dimensions of anxiety.

Factors influencing question-posing anxiety

Learner-specific factors

Findings

Students identified linguistic insecurity and fear of negative evaluation as key triggers. P3 noted that mentally translating from Chinese increased self-consciousness: “Sometimes I doubt if my question is even worth asking.” Several participants worried about appearing incompetent if their question was perceived as too basic, while others compared themselves unfavorably to more fluent peers. Personality differences shaped these experiences: the more extroverted participant expressed relative ease, while introverted peers were more prone to silence.

Interpretation

These findings confirm Bandura’s (1997) self-efficacy theory, where low confidence predicts avoidance behaviors, and aligns with Nation and Newton’s (2009) observation that metacognitive awareness of linguistic shortcomings can compound anxiety. Furthermore, four participants expressed a strong fear of negative evaluation3,28,30, fearing not only misunderstanding but also judgment from professors or peers. P3 vividly described the anxiety of imagining puzzled reactions or suppressed laughter in response to a seemingly simplistic question, a response consistent with Blascovich and Tomaka’s (1996) “challenge stress” framework. Participants also expressed concern over the perceived sophistication of their questions, with three individuals choosing silence when uncertain about basic concepts47,48. This reflects “face”-saving behavior common in Confucian-heritage learning cultures, where public displays of confusion may be seen as potentially disruptive rather than constructive49,50. While these anxieties were broadly shared, personality differences moderated their intensity. The only extroverted participant, P3, described relative ease with asking questions, viewing them more as casual conversation than academic risk—an effect consistent with Dewaele’s (2017) findings on extraversion buffering L2 anxiety51. Finally, while only P1 explicitly mentioned competitiveness, others’ narratives implied frequent self-comparisons to more fluent peers, echoing Liu and Jackson’s (2008) conclusion that even unspoken competition can amplify language anxiety by framing proficiency as a zero-sum contest5.

The critical role of teacher-student dynamics in questioning anxiety

Findings

The relationship between instructors and students emerged as a pivotal factor influencing learners’ willingness to pose questions in class. Participants’ accounts revealed that teacher behaviors—both verbal and nonverbal—could either alleviate or exacerbate foreign language anxiety (FLA), particularly in high-stakes academic interactions. Participants consistently emphasized the pivotal role of teacher receptivity in shaping their willingness to ask questions. Negative responses—ranging from overt dismissiveness to subtle cues like sighs or impatient gestures—had a lasting psychological impact (Table 5). As P2 recalled, a professor’s dismissive remark (“This was in the readings”) induced such humiliation that they refrained from asking questions for the rest of the semester.

Interpretation

This response reflects attachment theory, which conceptualizes teachers as “secure bases” for intellectual risk-taking; when this base is threatened, students may withdraw, especially those from collectivist backgrounds with heightened sensitivity to face-threatening situations52,53. A single negative incident can trigger an attributional spiral, where learners generalize the experience across contexts, reinforcing anxiety and avoidance behaviors54. In contrast, affirmative scaffolding from instructors had a significantly empowering effect. P4 described how their tutor’s practice of rephrasing student questions publicly clarified intent and validated the inquiry, an example of Vygotskian scaffolding (1978) that not only supports learning but also legitimizes participation55. However, participants also highlighted contradictions in classroom communication norms. Although instructors often stated that “no question is a bad question,” their implicit responses sometimes suggested otherwise. This mismatch, indicative of the hidden curriculum5, left international students—unfamiliar with local classroom schemas—struggling to decode appropriate participation cues. Moreover, cultural differences in feedback interpretation further intensified uncertainty. For instance, when a professor responded with “Interesting point” without elaboration, P1 was left anxious, uncertain whether it was genuine praise or polite dismissal. This reflects contrasting expectations: while British academics may favor indirect feedback, Chinese students often expect directive guidance and explicit correction56,57. These findings carry practical implications. Instructors can mitigate students’ anxiety by increasing awareness of nonverbal cues, implementing structured question protocols like “Think-Share-Refine” to ease spontaneous participation pressure, and using transparent metacommunication to affirm the value of basic questions. Collectively, such strategies can foster more inclusive and psychologically safe learning environments.

The legacy of educational socialization

Findings

Participants linked their reluctance to deeply ingrained learning habits from China. In teacher-centered classrooms, questioning was often seen as unnecessary or even disrespectful. P4 observed: “We were trained to absorb, not interrogate.” Even after moving to UK classrooms that encouraged interaction, students reported difficulty enacting new norms under pressure.

Interpretation

The participants’ accounts illustrate how question-posing anxiety was closely tied to deeply ingrained educational habits shaped by prior learning in China. This reflects what Jin and Cortazzi (2006) describe as pedagogical acculturation stress: the cognitive and emotional strain experienced when moving from teacher-centered to learner-centered environments58. Several participants recalled that in their earlier schooling, questioning was often interpreted as a challenge to authority or a sign of poor preparation. As P2 noted, such norms reinforced the Confucian-heritage model of the teacher as the “sage on the stage”59,60, where deference to authority outweighed active inquiry. Even after entering Western classrooms that actively encourage dialogue, this behavioral conditioning persisted. The difficulty lay not in a lack of awareness—students recognized that participation was valued—but in the conflict between ingrained deference and new expectations, a dynamic that resonates with Festinger’s (1957) theory of cognitive dissonance. Years of exam-driven, passive learning reinforced this inertia, leaving students underprepared for self-directed questioning practices61. The challenge was further compounded by the absence of prior opportunities to practice academic questioning, even in their first language, which carried into second-language contexts as a discursive disadvantage62.

Despite these constraints, participants also described gradual adaptation. For instance, P1 shared that by their third term, they had begun pre-writing questions before lectures to ease the transition into live classroom interaction. This incremental shift reflects Norton’s (2013) concept of investment, where learners negotiate and reshape their identities through sustained engagement with new cultural and linguistic practices63. To sum up, the findings underscore how educational socialization continues to influence participation patterns long after students move across contexts, yet also demonstrate that such patterns can be reshaped through time, practice, and supportive environments.

The temporal dynamics of questioning

Findings

Students described the timing of questions as a major factor shaping their anxiety. Several reported discomfort when needing to interrupt lectures, as it made them acutely self-conscious. P2 vividly compared this to “hitting pause on a movie everyone’s watching,” emphasizing the perceived disruption caused by drawing collective attention mid-explanation. By contrast, when instructors created structured opportunities for inquiry—for example, explicitly pausing to invite questions—participants felt legitimized to contribute. P3 explained that such invitations provided “permission to speak without guilt,” lowering the emotional risk of participation.

Interpretation

The accounts highlight how participation anxiety is not only about what students say but when they are expected to say it. Interrupting lectures imposed both cognitive and cultural burdens: cognitively, learners struggled with divided attention, needing to process new information while formulating questions, a situation consistent with Sweller’s (2011) cognitive load theory. Culturally, the act of breaking the lecturer’s flow conflicted with collectivist norms that prioritize group harmony and avoidance of disruption64,65,66. Together, these pressures made spontaneous questioning feel disproportionately risky. At the same time, the strong preference for structured questioning moments underscores the value of ritualized participation. As McHoul (1978) and Gray (1987) suggest, predictable routines can reduce ambiguity and buffer anxiety. What participants valued was not merely the opportunity to ask questions, but the clarity that it was the right time to do so. This nuance suggests that anxiety is as much situational as dispositional—rooted in the interaction between classroom structures and students’ prior cultural conditioning67.

Pedagogically, these insights point to the need for intentional classroom design. Incorporating short reflection pauses, using digital backchannels, or signaling designated moments for questions can make participation more accessible without diluting the spontaneity of academic dialogue. Such practices acknowledge the legitimate affective challenges faced by international students while also aligning with broader principles of inclusive pedagogy68. More broadly, the findings suggest that participation norms should not be assumed to be culturally neutral; rather, they need to be consciously negotiated in increasingly internationalized classrooms.

Navigating anxiety: student strategies for classroom participation

The experience of asking questions in a second language classroom represents a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and social challenges. For Chinese TESOL postgraduate students in UK universities, this act extends beyond mere language production—it becomes a negotiation of identity, competence, and belonging69. The strategies they develop reveal not only individual resilience but also the profound adaptability of learners operating at the intersection of cultural and educational systems.

The inner dialogue: cognitive reframing as emotional labor

Participants’ use of self-encouragement reflects more than simple positive thinking—it represents a sophisticated form of emotional labor70,71, where students consciously manage their affective responses to academic situations. As P2 shared: “There’s this moment where my heart races and I think ‘Don’t ask, just listen.’ But then I tell myself, ‘If you don’t ask now, you’ll spend hours later trying to figure it out alone.’ It’s like arguing with myself, but eventually the braver voice wins.”

This internal negotiation aligns with “metacognitive monitoring,” where learners observe and regulate their own thought processes. Students are, in effect, administering their own cognitive-behavioral strategies to counter years of educational conditioning that may have discouraged active questioning72. Each successful instance of asking a question becomes what Bandura (1997) terms a “mastery experience,” gradually eroding the foundation of self-doubt associated with question-posing anxiety.

Learning through others: the social scaffolding of confidence

The peer consultation strategy reveals a fascinating adaptation—students creating informal support networks to navigate unfamiliar academic terrain. P5’s account is particularly revealing: “I’ve identified ‘question champions’ in my class—those British students who always raise their hands. After lectures, I sometimes ask, ‘How did you know that was worth asking?’ Their answers give me a map of this invisible rulebook everyone else seems to have.”

This behavior reflects aspects of “legitimate peripheral participation” (Lave & Wenger, 1991), adapted into a highly active form. Rather than simply absorbing classroom norms, students strategically observe, question, and decode the unwritten rules of academic questioning73.

Their efforts to understand when and how others pose questions reveal how question-posing anxiety is shaped as much by social expectations and cultural norms as by linguistic processing. Crucially, students are not uncritically imitating Western peers but selectively adapting behaviors to align with their own communicative identities74.

Beyond the classroom: practice as identity work

Participants’ commitment to deliberate practice goes beyond improving fluency—it signifies a renegotiation of their identity as legitimate English users. P4 described this journey:

“At first I only practiced in my room, recording myself. Then I forced myself to join the debate society… Now I’m the one who volunteers to open the debate.”

This aligns with Norton’s (2013) notion of “investment,” where learners commit resources to develop desired identities75. The physical manifestations of question-posing anxiety—shaking hands, trembling voice—gradually diminish as students reframe questioning as an act of intellectual agency rather than a linguistic test76,77,78.

The debate society plays a crucial role because its communicative demands mirror those of classroom questioning: formulating arguments under pressure, anticipating responses, and making one’s voice heard. Thus, participants are not simply practicing English; they are explicitly rehearsing the assertive behaviors required for successful question-posing.

The body in the classroom: nonverbal communication as self-persuasion

One participant (P1) highlighted the influence of nonverbal behavior on managing question-posing anxiety:

“At home, good students sit quietly. Here, confident students lean forward and make eye contact. At first it felt like acting, but then something shifted—when my body pretended to be confident, my mind started to believe it.” This observation aligns with Damasio’s (1994) somatic marker hypothesis, which suggests bodily states can shape emotional experience. What begins as “pretending” becomes a form of embodied cognition that helps regulate anxiety and fosters more confident participation79.

Adopting confident body language also subtly shifts classroom power dynamics. As students appear more engaged, instructors respond more positively, reinforcing a cycle that gradually reduces question-posing anxiety. These strategies collectively reveal students’ remarkable resourcefulness but also highlight institutional gaps. Students expend significant cognitive effort to manage question-posing anxiety, often diverting mental resources from actual learning—what cognitive load theory terms “extraneous load”80.

Participants identified several unmet needs:

-

1.

Explicit instruction on the pragmatics of academic questioning.

-

2.

Structured peer mentoring to supplement informal networks.

-

3.

Faculty training on recognizing diverse participation styles.

-

4.

Asynchronous channels for posing questions without performance pressure.

Ultimately, these students’ strategies reveal both remarkable resilience and unnecessary hardship. Their experiences challenge us to create classrooms where linguistic and cultural diversity isn’t just accommodated, but truly valued—where the act of questioning becomes not a source of anxiety, but a celebration of intellectual curiosity in all its forms. The human cost of unaddressed participation anxiety extends beyond the classroom. As one participant (P3) reflected: “Every question I don’t ask is a connection I don’t make, an idea I don’t develop.” In an era of internationalized higher education, we cannot afford to let those potential connections go unmade.

Taken together, these findings illuminate the triggers of question-posing anxiety (RQ1), its impact on classroom participation (RQ2), and the strategies students develop to manage it (RQ3). Situating these insights within models of FLA deepens understanding of how affective factors operate in advanced, immersive learning environments. While the small sample (n = 5) limits generalizability, the depth and diversity of experiences provide transferable insights relevant to similar intercultural classroom contexts81.

Conclusion and implications

This study has provided a nuanced examination of the anxiety experienced by Chinese TESOL postgraduate students when asking questions in UK university classrooms. By exploring both the psychological and physiological dimensions of this phenomenon, as well as the coping strategies students employ, the research contributes to a deeper understanding of how language learners navigate the complex social and academic demands of studying abroad82.

Theoretical and empirical contributions

The findings extend existing theories of foreign language anxiety by demonstrating how anxiety manifests specifically in academic questioning contexts83. Participants reported cognitive interference, where excessive self-monitoring disrupted their ability to formulate questions, as well as physiological symptoms such as increased heart rate and speech disfluencies. These reactions were often exacerbated by cultural and educational dissonance—students struggled to reconcile their prior learning experiences, which emphasized passive knowledge reception, with the participatory expectations of Western classrooms. Notably, the study highlights the adaptive strategies students developed to manage their anxiety. These included cognitive reframing (e.g., positive self-talk), social scaffolding (e.g., peer consultation), and deliberate practice (e.g., targeted language exercises). These strategies reflect a sophisticated self-regulatory capacity, demonstrating how learners actively negotiate their affective and academic challenges45.

Practical implications for educators and institutions

For educators, the findings underscore the importance of creating inclusive classroom environments that acknowledge and address participation anxiety. To translate these insights into classroom practice, educators may consider the following strategies. First, structured interaction routines such as “Think-Pair-Share” can be used not only in seminars but also in large lectures by integrating short reflection breaks where students write down their questions, share with a peer, and then contribute to whole-class discussion84. This staged approach reduces the immediate pressure of public performance and allows students to rehearse both content and phrasing in a lower-stakes context. Second, instructors can model vulnerability by openly verbalizing their own uncertainties or by posing basic clarification questions during lectures. Such practices signal that questioning is a normal and valued part of academic discourse, thereby reducing students’ fear of negative evaluation. Third, to address the cultural variation in how feedback is interpreted, educators should develop sensitivity to nonverbal cues—such as hesitation, gaze avoidance, or physical withdrawal—that may indicate anxiety rather than disengagement. This can be supported by explicitly inviting students to signal confusion through alternative channels (e.g., anonymous online polls or written index cards) to complement verbal participation85. These strategies provide a toolkit for creating psychologically safe classrooms where participation is accessible to students with diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, embedding inclusive teaching practices into faculty evaluation and promotion mechanisms would also provide structural incentives for pedagogical innovation86.

Beyond classroom-level strategies, these findings also suggest a broader pedagogical shift within TESOL programs. Peer mentoring and the creation of “safe zones” for rehearsing questions should be institutionalized as part of program design rather than left to informal student networks. In seminar contexts, this may involve assigning rotating peer facilitators to guide small-group questioning practice, while in large lecture or online environments, digital platforms and breakout rooms can replicate these supportive spaces. Such practices not only normalize vulnerability but also reframe questioning as a collaborative rather than individual act. At the same time, teacher training curricula should explicitly incorporate intercultural communication skills and anxiety-sensitive pedagogy, equipping educators to interpret nonverbal signals of discomfort and to respond with constructive, inclusive feedback87. Embedding these practices into TESOL pedagogy strengthens teacher–student dynamics by shifting the focus from performance to engagement, ensuring that international students are supported not only linguistically but also affectively in their academic adaptation.

Limitations and future research directions

This study highlights the resilience of Chinese postgraduate students who must navigate not only linguistic barriers but also the cultural and pedagogical transitions that come with studying in the UK. Their experiences demonstrate that participation anxiety is not simply an individual shortcoming, but a systemic challenge that calls for institutional attention. Within the wider framework of internationalization in UK higher education, the findings underscore the need for alignment between classroom practices, program design, and institutional policies that genuinely support international students. This includes embedding intercultural communication and anxiety-sensitive pedagogy into faculty training, formalizing peer mentoring and transitional support programs, and recognizing inclusive teaching practices within evaluation and promotion systems. Such measures move beyond ad hoc classroom solutions and ensure that the inclusion of international students is built into the fabric of higher education.

At the same time, several limitations should be acknowledged. The small sample size (n = 5) necessarily limits the breadth of experiences captured and the generalizability of the findings. While the study aimed for maximum variation within the cohort, the sample may have excluded specific subgroups whose experiences with question-posing anxiety could differ in important ways. For example, none of the participants had more than one year of prior UK study experience, and the sample did not include students who had completed undergraduate degrees in the UK or who possessed extensive professional teaching experience. These groups may experience reduced anxiety due to greater familiarity with local academic norms, or, conversely, heightened anxiety arising from different forms of identity negotiation. The absence of these learner profiles suggests that the present findings reflect a particular moment in the adaptation trajectory rather than the full spectrum of possible experiences.

Ultimately, participation anxiety should not be viewed as a deficit to be corrected, but as an important signal of the affective demands of transnational education. Responding to it with empathy, pedagogical innovation, and sustained institutional commitment is essential if universities are to create equitable and empowering environments where all students can contribute fully to academic life. Future research would benefit from larger and more diverse samples—including students with long-term UK study histories, multilingual backgrounds beyond Mandarin-speaking contexts, or prior professional teaching experience—to capture a wider range of questioning behaviours and anxiety trajectories over time.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Huang. J. Students’ learning difficulties in a second language speaking classroom. In Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, 13-17 April 1998 (1998).

Woodrow, L. Anxiety and speaking English as a second language. RELC J. 37 (3), 308–328 (2006).

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B. & Cope, J. A. Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 70 (2), 125–132 (1986).

Tang, M. L. & Tian, J. R. The influences of EFL graduate students’ gender. In Major and English Proficiency on FLA (2019).

Liu, M. & Jackson, J. An exploration of Chinese EFL learners’ unwillingness to communicate and foreign language anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 92 (1), 71–86 (2008).

Carroll, J. B. A model of school learning. Teachers Coll. Record. 64 (8), 723–733 (1963).

Wang, Y. Q. & Wan, Y. S. Foreign Language Learning Anxiety and Its Influence on Foreign Language Learning-An Overview of Related Research at Home and Abroad (Foreign Language Teaching and Research, 2001).

Creswell, J. W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches (Sage, 2013).

MacIntyre, P. D. & Gardner, R. C. The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing in the second language. Lang. Learn. 44 (2), 283–305 (1994).

Young, D. J. Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does language anxiety research suggest? Mod. Lang. J. 75 (4), 426–439 (1991).

Li, J. Y. Psychological and neurobiological analysis of foreign language learning anxiety. J. Tianjin Foreign Stud. Univ. (2004).

Koch, A. K. & Terrell, T. D. Affective reactions of foreign language students to natural approach activities and teaching techniques. Mod. Lang. J. 75 (3), 307–318 (1991).

MacIntyre, P. D. Willingness to communicate in the second language: Understanding the decision to speak as a volitional process. Mod. Lang. J. 91 (4), 564–576 (2007).

MacIntyre, P. D. & Gardner, R. C. Methods and results in the study of anxiety and language learning: A review of the literature. Lang. Learn. (1991).

Gerencheal, B. R. & Horwitz, E. K. Foreign language anxiety, academic achievement, and the active girl/quiet boy hypothesis. Mod. Lang. J. 100 (1), 164–179 (2016).

Oxford English Dictionary. (Oxford University Press, 1885).

Spielberger, C. D. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983).

Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N. & Jackson, A. P. Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 92 (6), 131–143 (2007).

Kim, S. Academic oral communication needs of East Asian international graduate students in non-science and non-engineering fields. Engl. Specif. Purp. 25 (4), 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2005.10.001 (2006).

Dewaele, J. M. Psychological and sociodemographic correlates of communication anxiety in a second language. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 7 (1), 109–139 (2017).

Ghaemi, F. & Kharaghani, A. Foreign language speaking anxiety and self-confidence: A study of Iranian EFL learners. Procedia - Social Behaviora Sci. 30, 1712–1716 (2011).

Luo, X. Culture and anxiety: A cross-cultural study. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 20 (3), 269–275 (1996).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5 Ed. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (2013).

Carney, D. R., Cuddy, A. J. & Yap, A. J. Power posing: Brief nonverbal displays affect neuroendocrine levels and risk tolerance. Psychol. Sci. 21 (10), 1363–1368 (2010).

Yan, H. & Horwitz, E. K. Performance pressure in listening and speaking activities: A study of its impact on language learners. Lang. Learn. 58 (4), 759–781 (2008).

Barlow, D. H. Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic. 2 Ed. (Guilford Press, 2004).

Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. (Freeman, 1997).

Wang, P. & Roopchund, R. Chinese students’ English-speaking anxiety in asking questions in the MSc TESOL classroom. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. (2015).

Gregersen, T. Non-native speakers and communication: The effect of intercultural sensitivity. Lang. Intercultural Communication. 5 (3 & 4), 161–174 (2005).

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A. & &Oh, D. Theeffect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 78 (2), 169–183 (2010).

Phillips, E. M. The effects of language anxiety on students’ oral test performance and attitudes. Mod. Lang. J. 76 (1), 14–26 (1992).

Xiao, F. & Li, H. A comparative study of Chinese and American university students’ foreign language learning anxiety. Engl. Lang. Teach. 11 (1), 65–77 (2018).

Wang, L. & Roopchund, R. Factors influencing students’ communication with instructors in the classroom. Communication Educ. 64 (4), 452–466 (2015).

Horwitz, E. K. & Young, D. J. Language Anxiety: From Theory and Research To Classroom Implications (Prentice Hall, 1991).

Baran-Lucarz, M. Self-esteem, English language learning anxiety and English proficiency. Procedia - Social Behav. Sci. 158, 85–89 (2014).

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Sawyer, A. T. & Fang, A. The prevalence and correlates of anxiety and depressive disorders in youth: The role of self-reported physical fitness. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 43 (4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9658-z (2012).

Liu, M. A study of the relationship between foreign language anxiety and test performance among Chinese EFL learners. System 66, 94–104 (2017).

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101 (2006).

A British Educational Research Association. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. (2018). https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

MacIntyre, P. D. How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply to Sparks and Ganschow. Mod. Lang. J. 79 (1), 90–99 (1995).

Iverach, L., Menzies, R. G., Brian, O. & S Approach-avoidance in adults with stuttering: Testing the hypothesis of a dual phonological/semantic pathway. J. Fluen. Disord. 36 (1), 1–10 (2011).

Burgoon, J. K. Nonverbal signals. In Handbook of Interpersonal Communication (eds Knapp, M. L. & Miller, G. R.). 344–390. (Sage, 1994).

Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 10 (2), 144–156 (2003).

Chen, T. Environmental anxiety and personality anxiety: A study of their mutual amplification and mutual attenuation. J. Anxiety Stress. 5 (2), 123–136 (1997).

Price, M. L. The subjective experience of foreign language anxiety: Interviews with highly anxious students. Foreign Lang. Annals. 24 (3), 239–258 (1991).

Clark, D. A. & Beck, A. T. Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders: Science and Practice (Guilford Press, 2010).

Dewaele, J. M. Emotions in Multiple Languages. (Palgrave Macmillan).

Putwain, D. W., Daly, A. L., Sadreddini, S. & Chamberlain, S. Academically buoyant students are less anxious about and perform better in high-stakes examinations. Br. Psychol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12068 (2015).

MacIntyre, P. D., Dörnyei, Z., Clément, R. & Noels, K. A. Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Mod. Lang. J. 82 (4), 545–562 (1998).

Abu-Rabi, A. Islam at the Crossroads: On the Life and Thought of Bediuzzaman Said Nursi (SUNY, 2004).

Lader, M. H. Anxiety or depression as a cause of psychosomatic symptoms. In Psychology and Medicine (eds Lader, M. H. & Burnet, T.). 227–242. (Wiley, 1984).

Liu, M. & Zhang, L. J. Anxiety in Chinese EFL learners across different levels of English proficiency. J. Multiling. Multicultural Dev. 38 (6), 536–549 (2017).

Jin, L., Debot, K. & Keizer, S. Revisiting the role of anxiety in foreign language achievement: the interaction between anxiety and attitude. Mod. Lang. J. 99 (4), 660–675 (2015).

Merriam, S. B. Qualitativeresearch:Aguidetodesignandimplementation (Jossey-Bass., 2009).

Elkhafaifi, H. Listening comprehension and anxiety in the Arabic language classroom. Mod. Lang. J. 89 (2), 206–220 (2005).

Dillon, C. L. Questioning in group discussions: The effects of a content-preknowledge hypothesis and teacher questioning techniques. J. Educ. Psychol. 80 (4), 349–355 (1988).

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R. & Calvo, M. G. Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion 7 (2), 336–353 (2007).

Nation, P. & Newton, J. Teaching ESL/EFL Listening and Speaking. (Routledge , 2009).

Hewitt, P. L. & Flett, G. L. Perfectionismintheselfandsocialcontexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 60 (3), 456–470 (1991).

Steinberg, J. & Horwitz, E. K. The effect of induced anxiety on the denotation of English and French nouns. Lang. Learn. 36 (3), 339–363 (1986).

Aida, Y. Examination of Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope’s construct of foreign language anxiety: The case of students of Japanese. Mod. Lang. J. 78 (2), 155–168. (1994).

Roulston, K. Considering quality in qualitative interviewing. Qualitative Res. 10 (2), 199–228 (2010).

Chen, G. Functional role of positive emotions in coping with stress during a simulated acute stress task. Motivation Emot. 21 (3), 241–257 (1997).

MacIntyre, P. D. & Charos, C. Personality, attitudes, and affect as predictors of second language communication. J. Lang. Social Psychol. 15 (1), 3–26 (1996).

Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S. (eds) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (Sage, 2018).

Chastain, K. Affective and ability factors in second language acquisition. Lang. Learn. 25 (1), 153–161 (1975).

Liu, M. Motivation, Language Identity and the L2 Self (Bristol University, 2015).

Canale, M. & Swain, M. Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Appl. Linguist. 1 (1), 1–47 (1980).

Dörnyei, Z. The Psychology of the Language Learner: Individual Differences in Second Language Acquisition (Routledge, 2005).

Li, X. Communicative anxiety, avoidance strategies, and classroom participation: A study of EFL learners in China. System 82, 1–10 (2019).

Jennings, P. A. & Greenberg, M. T. The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79 (1), 491–525 (2009).

Donovan, L. A. & MacIntyre, P. D. Age and sex differences in willingness to communicate, communication apprehension, and self-perceived competence. Communication Res. Rep. 22 (3), 207–215 (2005).

Liu, M. Anxiety in Chinese EFL students at different proficiency levels. System 35 (3), 335–344 (2007).

Goldberg, L. R. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychol. Assess. 4 (1), 26–42 (1992).

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T. & Tesch-Römer, C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol. Rev. 100 (3), 363–406 (1993).

Young, D. J. The relationship between anxiety and foreign language oral proficiency ratings. Foreign Lang. Annals. 19 (5), 439–445 (1986).

Gardner, R. C. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. (Edward Arnold, 1985).

Furnham, A. & Haeven, H. Personality and learning style correlates of attitudes to school subjects and teacher. Educational Psychol. 19 (1), 59–68 (1999).

Zimmerman, B. J. Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Pract. 41 (2), 64–70 (2002).

Gardner, R. C., Smythe, P. C., Clement, R. & Gliksman, L. Second language learning: A social psychological perspective. Can. Mod. Lang. Rev. 32 (3), 198–213 (1976).

Naiman, N., Frohlich, M., Stern, H. H. & Todesco, A. The good Language learner. TESOL Can. J. 5 (1), 18–34 (1978).

Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z. & Oswald, F. L. Deliberate practice and performance in music, games, sports, education, and professions: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Sci. 25 (8), 1608–1618 (2014).

Young, D. J. An investigation of students’ perspectives on anxiety and speaking. Foreign Lang. Annals. 23 (6), 539–553 (1990).

Phillips, D. The effects of language anxiety on students of Japanese in New Zealand. System 20 (3), 353–364 (1992).

Liu, M. & Zhang, L. J. Foreign language learning anxiety in China. System 36 (2), 194–205 (2008).

Lalonde, R. N., Moorcroft, R. & Evers, W. F. A preliminary investigation of second language anxiety: A study of adult learners of French. Foreign Lang. Annals. 20 (5), 423–428 (1987).

O’ Reilly, M., Ronzoni, P. & Ogra, A. Subjectivity and reflexivity in the social sciences: Epistemic windows and methodological consequences. Sociology 47 (4), 765–781 (2013).

Acknowledgements

DeclarationsEthics Approval: This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Moray House School of Education and Sport, The University of Edinburgh (Reference No. EDU-IRB-2023-78). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, including the British Educational Research Association (BERA) Ethical Guidelines (2018).Consent to Participate: All participants provided informed written consent prior to their participation in this research. Participants were assured of confidentiality, anonymity, and the right to withdraw at any point without consequence.Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yuanzhe Li; Methodology, Yuanzhe Li and Wending Liu; Validation, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Formal Analysis, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Investigation, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Resources, Yuanzhe Li and Wending Liu; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Yuanzhe Li; Writing—Review and Editing, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Visualization, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Supervision, Wending Liu; Project Administration, Yuanzhe Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.Funding Declaration: This research was funded by Enerstay Sustainability Pte Ltd (Singapore) Grant Call (Call 1/2022) _SUST (Project ID BS-2022), Singapore.Data Availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.Competing Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Yuanzhe Li; Methodology, Yuanzhe Li and Wending Liu; Validation, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Formal Analysis, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Investigation, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Resources, Yuanzhe Li and Wending Liu; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Yuanzhe Li; Writing—Review and Editing, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Visualization, Yuanzhe Li and Eyu E; Supervision, Wending Liu; Project Administration, Yuanzhe Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Moray House School of Education and Sport, The University of Edinburgh (Reference No. EDU-IRB-2023-78).

Consent to participate

All participants provided informed written consent prior to their participation in this research. Participants were assured of confidentiality, anonymity, and the right to withdraw at any point without consequence.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

E, E., Liu, W. & Li, Y. A qualitative study of question-posing anxiety in Chinese postgraduates in UK TESOL programs. Sci Rep 16, 2081 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31915-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31915-0