Abstract

Under complex working conditions, traditional fault detection methods have limitations like many parameters and complex calculations. To solve this, a bearing fault detection model based on smooth dilated convolution and shuffling algorithm was proposed. It uses smooth convolution kernels to capture local vibration-signal features, reduces computational complexity via group convolution and channel washing, simplifies the structure with network pruning and knowledge distillation, and combines bidirectional gated recurrent units and generative adversarial networks to capture long-term dependencies. Compared with existing methods, it significantly cuts the number of model parameters and reasoning time while keeping detection accuracy. Experimental data shows that in the sample classification task, its accuracy rate is 97.88%, average reasoning time is 274 fps, computational cost is 1.66 FLOPs, and parameter quantity is 7.76 M, all better than comparison models. In bearing feature extraction and fault detection tasks, its average fitting accuracy is 96.13% and detection accuracy is 99.62%, also better than comparison models. The research suggests the model can balance model lightweighting and detection performance, and is suitable for real-time fault monitoring in resource-constrained scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

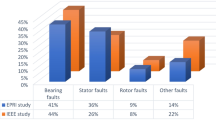

Bearings act as essential components in rotating machinery, and their operating conditions directly influence both the safety and service life of the equipment. Timely fault diagnosis of bearings helps lower maintenance costs and enhances production safety1. However, under practical conditions, bearing vibration signals are affected by noise and varying operating conditions. Manual inspection or simple signal processing cannot identify weak fault features. Intelligent algorithms are needed to achieve high-accuracy bearing fault detection2,3. In recent years, numerous researchers have conducted extensive studies on bearing fault detection. Al Mamun A et al. introduced a multi-sensor fusion approach to handle high-dimensional bearing data. They used frequency analysis to construct a heterogeneous frequency tensor, applied multilinear principal component analysis for decomposition, extracted signal features, and combined them with neural networks for anomaly detection. This method realized bearing fault diagnosis under complex vibration signals4. S. Mitra and C. Koley proposed a vibration signal analysis method based on wavelet super-resolution and two-dimensional convolutional neural network to improve detection under harsh working conditions. They collected vibration signals from variable frequency drive induction motors, extracted features using continuous wavelet transform, Stockwell transform, and adaptive super transform, and applied super-resolution optimization for classification. This method achieved high-accuracy fault detection5. R. K. Mishra et al. put forward a time-domain signal processing method to solve the low efficiency of bearing fault detection. They generated fault vibration features from velocity components, transformed them into image features through windowed two-dimensional vibration imaging, and extracted features with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). They used support vector machines for classification6. R. Dubey et al. put forward a method based on variational nonlinear chirp mode decomposition to improve classification accuracy. They initialized parameters with instantaneous frequency, used scale-space representation for amplitude spectrum boundary detection, and classified signals with feedforward neural networks. Experimental results showed that the classification accuracy reached 97.52%7.

With the advancement of big data analytics and artificial intelligence technologies, neural networks show strong advantages in pattern recognition and feature extraction, which provide new approaches for bearing fault diagnosis. CNN captures temporal dependencies through stacked convolution layers and fully connected layers. It is capable of automatically capturing multi-scale features from vibration signals and has seen wide application in bearing fault diagnosis8,9. However, conventional CNN for bearing fault detection has the limitations of large parameter size and complex computation. There is a need for lightweight and efficient deep learning models10. Smoothed Dilated Convolution (SDC) uses learnable smoothed kernels to fuse local neighborhoods. It keeps the advantage of a large receptive field while enhancing the ability to capture local details11. For high-dimensional bearing data, lightweight feature extraction modules can be introduced for more efficient signal feature extraction. The Shuffle algorithm applies grouped convolution and channel shuffle to achieve cross fusion of heterogeneous features and reduce parameters and computation12. Residual Network (ResNet) applies residual connections for identity mapping, which reduces parameter size and improves feature reuse13. Therefore, this study proposed a bearing fault detection model based on SDC. It integrates shuffle for lightweight design and applies ResNet to further improve accuracy. The model aims to achieve lightweight feature extraction for bearing vibration signals and meet the requirements of high accuracy, low latency, and low cost detection. It provides algorithm support for lightweight bearing fault detection. The innovation of the research lies in the integration of smooth dilated convolution, shuffling mechanism and residual structure to construct a deep neural network model that is efficient, lightweight and has strong feature expression ability, which is used for intelligent diagnosis of bearing faults. This model enhances the local feature perception ability by smoothing dilated convolution, expanding the receptive field while reducing the computational cost. Introduce a shuffling module to promote information exchange between channels and improve feature utilization while reducing the number of parameters. Combining residual structures to alleviate the degradation problem of deep networks and enhance the efficiency of gradient propagation.

The contribution highlight of the article lies in proposing a lightweight deep neural network model that integrates smooth dilated convolution, shuffling mechanism and residual structure, effectively balancing the complexity of the model and the accuracy of fault identification. It has solved the problems of large parameter quantity and low feature extraction efficiency of the current conventional CNN under complex working conditions, and achieved the collaborative optimization of high precision and lightweight.

Research design

Bearing signal feature extraction method based on SDC

In complex working conditions, bearing vibration signals have high dimensionality and non-uniform distribution. Although CNN extracts local features through stacked kernels, it still has the limitations of large parameter size and complex computation. A lightweight and efficient deep learning model is needed14. SDC introduces local smoothing on the basis of conventional dilated convolution. It avoids the problem of broken sampling points in feature extraction. Therefore, a bearing signal feature extraction method based on SDC is proposed to improve the completeness and reliability of signal extraction. SDC expands the receptive field and realizes local compensation of pulse information in bearing signals to avoid the loss of contextual information15. The calculation of receptive field range is shown in Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), \(R_{f}\) represents the receptive field range of the convolution kernel, \(K_{conv}\) represents the size of the convolution kernel, and \(R_{d}\) represents the void rate. When the void rate is greater than 1, dilated convolution may cause discontinuous feature sampling while expanding the receptive field. Then, based on the defined receptive field, SDC combines local smoothing with dilated kernels to realize multi-scale feature fusion. The output features of dilated kernels are shown in Eq. (2).

In Eq. (2), \(Y(i,j)\) represents the output feature, \(w(m, \, n)\) represents the position weigh. By combining local detail capture and global dependency modeling, SDC reduces the problem of gradient vanishing16. Therefore, SDC achieves high-accuracy multi-scale feature extraction with small kernels and mean filtering. Local smoothing operation is to dynamically reinforce the transition regions between sparse sampling points in the input feature map by introducing a learnable weight matrix during the dilated convolution process, thereby reducing the information distortion caused by the increase in sampling intervals. This operation combines small-scale convolution kernels with mean filters, which retain high-frequency details while suppressing noise interference, further enhancing feature continuity and robustness.

The main difference between SDC and the existing smooth convolution lies in that SDC enhances the model’s adaptability to complex working conditions without increasing the network depth by adaptively adjusting the void rate and smoothing weights. However, traditional smooth convolution only relies on smooth kernels of a fixed scale, making it difficult to achieve a coordinated expression of both local details and global structure. In addition, SDC introduces a differentiable void rate optimization strategy, enabling the network to dynamically select the optimal receptive field based on the frequency domain characteristics of the input signal during the training process, thereby enhancing the ability to identify bearing fault features under variable operating conditions.

The derivation process of the local smoothing operation is as follows: Let the response of the input feature map at position x be a, and the sampling interval of the dilated convolution be d. Then, the local smoothing operation is defined as weighted interpolation of the implicit response within the neighborhood of the non-zero sampling point. Introduce a learnable weight matrix S, perform mean filtering on the original input to obtain smooth components, and then fuse the original features and smooth features through a gating mechanism. The structure of SDC is shown in Fig. 1.

As shown in Fig. 1, SDC first converts input signals of different scales into sequence features and applies mean convolution for local smoothing. Then, it generates several multi-scale feature maps through interval subsampling and captures temporal dependencies under different scales with shared convolution. Finally, it introduces a layer interaction mechanism to fuse the outputs of kernels and obtain the final result. SDC expands the receptive field and improves the completeness of multi-scale feature extraction. However, under strong noise, SDC still lacks robustness. Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) reduces background noise through the dynamic game between generator and discriminator17. Therefore, GAN is combined with SDC to improve efficiency of feature extraction. Under complex conditions, GAN maps local neighborhoods adaptively according to target working states and distinguishes true and false samples with the target function18. The target function of GAN is defined in Eq. (3).

In Eq. (3), \(\mathop {\min }\limits_{G} \mathop {\max }\limits_{D} V(\overline{D},\overline{G})\) is the objective function, \(E_{{x \sim P_{data} (x)}}\) is real samples \(x\) sampled from real distribution \(P_{data} (x)\). \(E_{{z \sim P_{z} (z)}}\) represents the random noise vector \(z\) sampled from the Gaussian noise distribution \(P_{z} (z)\), \(\overline{D}(x)\) represents the probability of the discriminator determining the real sample, %, and \(\overline{G}(z)\) represents the mapping of the mapping noise of the generator. To prevent gradient interference, the generator was kept fixed while the discriminator was optimized to enhance convergence19. The discriminator’s optimization function is presented in Eq. (4).

In Eq. (4), \(D_{G}^{*} (x)\) represents the optimization function of the discriminator, and \(P_{g} (x)\) represents the state of generating false samples, that is, the sample data generated by the generator, whose distribution approximates that of the real data but is a forged sample. Based on this, GAN is combined with SDC to raise a denoising method for bearing signals, named GAN-SDC, to enhance robustness and noise resistance. The detailed flow of GAN-SDC is shown in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 2, the algorithm first decomposes original vibration signals into sample inputs and noise components. Then, the generator maps random noise vectors layer by layer and applies smoothed kernels to enhance continuity of generated samples. Finally, the SDC module fuses output features and generates the final denoised vibration signal features. Because bearing signals have strong heterogeneity, GAN-SDC still lacks effective representation in low-frequency signals. To further improve multi-scale feature extraction accuracy, Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) is introduced. CBAM assigns weights to both input sequences and output features of convolution, and enhances key features through weighted averaging20. The attention weighting operation is defined in Eq. (5).

In Eq. (5), \({\text{Attention}}(Q,K,V)\) represents the attention function, \({\text{softmax}}(.)\) represents the probability distribution. With dual attention weighting, feature extraction becomes more comprehensive and effective. Therefore, on the basis of GAN-SDC, an improved method named GAN-SDC-CBAM is raised to achieve complete feature extraction of bearing vibration signals. The detailed flow of GAN-SDC-CBAM is shown in Fig. 3.

In Fig. 3, the algorithm introduces spatial attention to reduce the dimension of original sequences. It applies average pooling on channels, spatial height, and width. It multiplies matrices to fuse features and reduce redundant information. In addition, in the output of the SDC module, channel attention is applied. Global pooling and fully connected layers perform nonlinear mapping. Weights are adjusted adaptively with dilated convolution features. Dual activation functions are applied for channel weighting to strengthen key features. In this way, GAN-SDC-CBAM achieves high-accuracy extraction of bearing vibration signals under strong noise interference.

Lightweight feature extraction design based on shuffle and ResNet

Although the GAN-SDC-CBAM algorithm improves the completeness of bearing vibration signal extraction, it still has the limitations of high computational complexity and insufficient transfer adaptability. To solve the problem of heavy convolution computation, a lightweight algorithm is needed to improve feature extraction efficiency. Shuffle reduces parameters and computational cost through grouped convolution and channel shuffle21. Therefore, Shuffle is combined with GAN-SDC-CBAM to achieve lightweight feature extraction of bearing vibration signals. In branch division, Shuffle calculates features with both standard convolution and grouped convolution22. The parameter size and computational cost under standard convolution are shown in Eq. (6).

In Eq. (6), \(P_{co}\) and \(F_{co}\) represent the parameter size and computational cost under standard convolution. \(C_{in}\) and \(C_{out}\) are the input and output channel. Then, grouped convolution is applied to the main branch for depthwise separable convolution, and its parameter size and computational cost are shown in Eq. (7).

In Eq. (7), \(P_{dw}\) and \(F_{dw}\) represent the parameter size and computational cost under grouped convolution. By combining the outputs of standard convolution and grouped convolution, the channel shuffle mechanism fuses features. Shuffle improves cross-channel information interaction while reducing parameters. The work flow of Shuffle is illustrated in Fig. 4.

As shown in Fig. 4, the algorithm first preprocesses bearing vibration features, extracts channel number and feature map size, and divides them into main and auxiliary branches. The main branch applies 3 × 3 depthwise separable convolution to compress feature maps and complete downsampling with nonlinear mapping. Finally, the auxiliary branch output is fused with channel shuffle. The activation function outputs the final signal features. Although Shuffle achieves lightweight feature extraction, gradient vanishing and unstable convergence still exist in deep stacking of GAN-SDC-CBAM. ResNet solves this problem with identity mapping, which improves stability in training. Therefore, ResNet is combined with Shuffle to raise a lightweight framework named Shuffle-ResNet. ResNet uses skip connections to map convolution outputs of Shuffle and improve information utilization23. The forward equation is shown in Eq. (8).

In Eq. (8), \(H(x)\) represents the identity mapping function. Then, backpropagation optimizes residual mapping, which enhances flexibility and robustness. The gradient equation of backpropagation in ResNet is shown in Eq. (9).

In Eq. (9), \(loss\) represents the loss function. \(x_{i} (i = 1,2, \cdots ,L)\) represents the output feature of the \(i\)-th residual unit. ResNet avoids gradient vanishing by regularization and backpropagation. It improves feature utilization in Shuffle24. The detailed flow of Shuffle-ResNet is shown in Fig. 5.

In Fig. 5, the algorithm first normalizes the input signal. Shuffle divides branches, and channel shuffle fuses outputs of standard convolution and grouped convolution. The features are fed into convolution layers of residual blocks. Then, ResNet regularizes the forward propagation of each residual block and applies skip connections to transfer gradients. Information is fully fused across groups. Finally, global average pooling is applied through stacked layers, and optimized features are obtained. However, direct fusion of Shuffle-ResNet and GAN-SDC-CBAM reduces inference speed. A simplified structure is needed for deployment. NP removes redundant parameters and connections through structured pruning, which reduces model size25. KD transfers knowledge between models of different sizes and compensates for the accuracy gap in lightweight models26. Therefore, NP and KD are used in two-stage optimization to reduce structural complexity. KD measures the difference of probability distributions with a distillation loss function. The function is shown in Eq. (10).

In Eq. (10), \(L_{KD}\) represents the distillation loss function. \(\lambda\) represents the balance coefficient. \(l_{s}\) and \(l_{t}\) represent the output vectors of small and large models. \(t\) represents the target. \(T\) represents the hyperparameter. \(M(.)\) represents the gap between outputs of large and small models. By optimizing the distillation loss, the difference in accuracy between models decreases. Therefore, Network pruning (NP) and Knowledge Distillation (KD) are combined with Shuffle-ResNet and GAN-SDC-CBAM to raise a lightweight model for bearing feature extraction, named SDC-Shuffle-ResNet. The model first normalizes input signals. It applies spatial attention of CBAM and combines local smoothing to connect context information. GAN optimizes feature distribution, and dilated convolution expands the receptive field. Then, NP simplifies weights, and grouped convolution is applied to residual blocks. Channel shuffle enhances information interaction. Finally, CBAM applies channel attention to ResNet outputs. Global average pooling is applied, and KD optimizes distillation loss. In this way, the model extracts key features of bearing vibration signals.

Bearing fault detection model construction with BiGRU

Although the SDC-Shuffle-ResNet model achieves lightweight extraction of bearing vibration signals, it still faces limitations in real-time fault detection and accuracy. A method that balances temporal modeling and lightweight computation is needed for real-time monitoring of bearing faults. Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) fully utilizes historical and future information through update and reset gates to capture long-term dependencies in non-stationary signals27. Therefore, BiGRU is applied to time-series prediction of bearing signal features for real-time fault detection. BiGRU first updates memory states with a dual-gate mechanism through unidirectional GRU units to address gradient explosion28. The computation of the dual-gate mechanism is shown in Eq. (11).

In Eq. (11), \(z_{t}\) and \(r_{t}\) are the update and reset gate vectors. \(\sigma\) represents the activation function. \(b_{z}\), \(b_{r}\), and \(b_{h}\) are bias terms. \(r_{t} \odot h_{t - 1}\) is the reset operation on historical information. The hidden state is further updated based on outputs of update and reset gates. The update operation is shown in Eq. (12).

In Eq. (12), \(V(.)\) represents a vector function. \(\hat{h}_{t}\) represents the BiGRU output vector. \(\oplus\) represents vector concatenation. With bidirectional propagation of historical and future information, BiGRU adaptively interprets complex non-stationary features. The network first enhances input signal features and converts them into sequences of different time steps. Forward gradients compute forward vectors, and backward gradients compute backward vectors, fully utilizing historical and future information. Bidirectional weighted fusion concatenates vectors, and convolution and attention mechanisms complement features, enabling prediction of vibration signal features. Although BiGRU effectively detects fault signal features, it still lacks global feature interaction and generalization. Graph Attention Network-v2 (GATv2) captures global and non-local dependencies to enhance feature interaction and model robustness29. Therefore, GATv2 is combined with BiGRU to propose a fault detection method named GAT-BiGRU for precise detection of weak fault signals. GATv2 assigns attention weights to neighboring nodes to improve global dependency modeling30. The computation of graph attention coefficients is shown in Eq. (13).

In Eq. (13), \(e_{ij}\) represents the graph attention coefficient. \({\text{LeakyReLU(}}{.)}\) represents the leaky ReLU function. \(\beta\) represents a trainable weight matrix. Attention coefficients score a feedforward neural network, and normalized outputs produce key signal features. The output feature of GATv2 is shown in Eq. (14).

In Eq. (14), \(F\) represents the output feature. \(\Omega\) is the set of neighbors of node \((i,j)\). Global dependency representation of GATv2 enhances BiGRU’s interaction with non-local features31. GAT-BiGRU combines bidirectional gating and graph attention, improving fault detection robustness. The network first decomposes the original vibration signal into graph-structured features and extracts node features based on similarity and temporal adjacency. GATv2 calculates attention coefficients between nodes for weighted aggregation. BiGRU performs bidirectional propagation on node features to capture long-term dependencies and non-stationary patterns. Weighted fusion merges subnetwork outputs, and a fully connected layer outputs the bearing fault type. GAT-BiGRU achieves precise detection of fault signals through spectral decomposition. The spectral decomposition equation is shown in Eq. (15).

In Eq. (15), \(F_{ro}\), \(F_{in}\) and \(F_{out}\) respectively represent the fault characteristic frequencies of the bearing rolling elements, inner ring and outer ring, with the unit of Hz. \(N\) represents the number of rolling elements, \(f_{r}\) represents the rotation frequency of the inner ring, with the unit of Hz. \(d\) represents the diameter at the pitch circle of the roller, with the unit of mm. \(D\) represents the pitch diameter of the bearing, with the unit of mm. \(\alpha\) represents the radial contact Angle, with the unit of °. By computing different fault characteristic frequencies, the output features of SDC-Shuffle-ResNet are classified. Therefore, GAT-BiGRU is combined with SDC-Shuffle-ResNet to propose an improved bearing fault detection model, named SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU, achieving lightweight feature extraction and intelligent fault detection. The extraction flow is shown in Fig. 6.

In Fig. 6, the model segments the original vibration signal into windows and normalizes them for temporal features. GAN denoises the sequence, and SDC alleviates the gridding effect of dilated convolution. Residual skip connections provide identity mapping of convolution features. Shuffle’s grouped convolution and channel shuffle lighten convolution branches, and KD optimizes distillation loss. GATv2 and BiGRU model global dependencies, fuse sequences across multiple branches, and channel attention further enhances key features. The model outputs the final bearing fault signal features. In summary, SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU introduces Shuffle and ResNet for lightweight feature extraction, uses SDC for feature completeness, and combines GAT-BiGRU with spectral decomposition to improve stability and achieve precise fault signal detection.

To ensure that the model can still maintain a relatively excellent diagnostic accuracy and efficiency in real environments, the study adopted the bearing dataset provided by the University of Paderborn and real working condition data for model training and validation. This dataset covers various types of bearing faults (such as rolling element damage, inner ring cracks, outer ring spalling, etc.) as well as vibration signal data under different working conditions (different speeds, loads), and is highly representative and challenging. The real operating condition data is collected from the long-term operating equipment in the industrial site, which contains rich noise interference and operating condition fluctuations, and can effectively test the robustness of the model in complex industrial environments.

Results and analysis

Verification of model computational performance

To verify the computational performance superiority of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model, it was compared with Back Propagation Neural Network-Unscented Kalman Filter (BPNN-UKF), Temporal Convolutional Network-Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (TCN-BiLSTM), and Variational Mode Decomposition-Kernel Extreme Learning Machine (VMD-KELM). To ensure the authenticity of the data, the experimental verification was conducted using the bearing dataset provided by the University of Paderborn. This dataset contains vibration signals under normal conditions and various fault types under different loads and rotational speeds. The experiment selected three types of typical fault samples with a sampling frequency of 48 kHz, and 1000 sets of data for each type were used for model training and testing. In addition, it also includes the verification of practical scenarios in real industrial Settings, collecting the bearing vibration signals of the actual operating units in a certain wind farm, with a sampling frequency of 20 kHz, covering 200 sets of data under different working conditions. The experiments were performed on Ubuntu 22.04 with CUDA 11.8, using an Intel i7-12700 CPU and an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. The AdamW optimizer was applied with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 64. Initially, the accuracy and loss values for the sample prediction task were compared, and the results are presented in Fig. 7.

In Fig. 7a, the accuracy curve of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model reached a stable trend after 23 iterations, which was fewer than the comparison models. The model achieved an average accuracy of 97.88% for the sample classification prediction task, improving by 1.45% compared with the highest value of the comparison models, indicating better sample prediction performance. In Fig. 7b, the average loss function value of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model for the sample classification prediction task was 2.26, which was 0.68 lower than the minimum value of the comparison models. The convergence speed was also higher than that of the comparison models, further confirming the superior sample prediction performance of the model. To assess the model’s advantage in the sample classification task, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to examine the relationship between sensitivity and specificity, along with precision, recall, and F1 score for a comprehensive comparison. The results are illustrated in Fig. 8.

In Fig. 8a, the ROC curve of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model was closer to the upper-left corner, indicating higher sample classification accuracy. The Area Under Curve (AUC) value of the model was 0.8917, which was 0.0916 higher than the maximum value of the comparison models, confirming the superior sample classification performance. As shown in Fig. 8b, SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU achieved a precision of 95.74% and a recall of 90.08%, improving by 2.52% and 2.81% compared with the maximum values of the comparison models, further demonstrating its superiority in sample classification performance. To further evaluate the computational cost, the maximum number of iterations was set to 200. The BPNN-UKF, TCN-BiLSTM, VMD-KELM, and SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU models were numbered from 1 to 4. The inference time, computation, and parameter quantity were compared for the sample classification prediction task. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 9.

As shown in Fig. 9a, the inference time curve of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model was relatively stable, indicating more stable inference performance. The average inference time of the model was 274 fps, which increased by 170 fps, 129 fps, and 68 fps compared with BPNN-UKF, TCN-BiLSTM, and VMD-KELM, respectively, demonstrating higher efficiency in sample classification prediction. In Fig. 9b, the computation of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model was 1.66 FLOPs, and the parameter quantity was 7.76 M, which decreased by 0.31 FLOPs and 9.92 M compared with the minimum values of the comparison models, indicating better lightweight performance. This was due to the use of Shuffle’s grouped convolution and channel shuffle mechanism to reduce computational complexity, the use of ResNet skip connections to further simplify the model structure, and the combination of NP and KD to effectively reduce parameter quantity, achieving lightweight computation.

The lightweight standard proposed in the research is to control the number of model parameters within 60% of the original model while ensuring the accuracy of feature extraction, reduce the computational load to 50% of the original, and maintain sensitivity to key fault features at the same time. Compared with the benchmark model of the unintroduced shuffling mechanism and knowledge distillation proposed in the study, DCC-Shufflet-BIGRU reduces the number of parameters by 58.3%, and the computational load is reduced to 46.7% of the original model, meeting the lightweight design standard.

Verification of bearing signal feature extraction ability

Based on the verification of sample classification prediction performance and inference efficiency of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model, its application in bearing signal feature extraction was further evaluated. The amplitude and acceleration of bearing vibration signals were used to validate the feature extraction accuracy. Initially, the model’s fitting performance on the original bearing vibration signals was evaluated by comparing frequency-domain and envelope spectrum plots. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 10.

As shown in Fig. 10a, the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model fitted the bearing vibration signals well, achieving an average fitting accuracy of 96.13%. When the frequency was below 1,200 Hz, the predicted amplitude curve fluctuated, and the fitting accuracy was 85.24%, which largely satisfied the extraction requirements of low-frequency bearing signal features. As shown in Fig. 10b, SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU achieved a fitting accuracy of 97.36% for the modulation effect of amplitude over time, accurately identifying key vibration features at different frequencies. These results indicated that the model produced accurate bearing feature extraction, providing reliable data support for subsequent fault detection. To further confirm the model’s advantage in fitting bearing vibration signals, its amplitude fitting performance was compared with different models. The results are shown in Fig. 11.

As shown in Fig. 11, the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model achieved a Coefficient of Determination (R2) of 0.96 for amplitude fitting, which improved by 0.09, 0.14, and 0.15 compared with BPNN-UKF, TCN-BiLSTM, and VMD-KELM, respectively. Additionally, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of amplitude prediction was 0.14 mm, which decreased by 0.10 mm, 0.28 mm, and 0.09 mm compared with BPNN-UKF, TCN-BiLSTM, and VMD-KELM, indicating that the proposed model achieved more accurate and stable amplitude fitting and prediction. To further verify the model’s superiority in predicting vibration signal trends, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and RMSE of amplitude acceleration prediction were used. The results are shown in Fig. 12.

In Fig. 12a, the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model achieved an average MAE of 2.59 mm2/s in the training set and 2.88 mm2/s in the validation set, which decreased by 0.11 mm2/s and 0.16 mm2/s compared with the minimum values of the comparison models, indicating better prediction performance for amplitude variations. In Fig. 12b, the average RMSE of amplitude acceleration in the training and validation sets was 4.86 mm2/s and 5.12 mm2/s, which decreased by 0.26 mm2/s and 0.09 mm2/s compared with the minimum values of the comparison models, further confirming the model’s superior fitting ability for amplitude variations. This performance was attributed to the deep separable convolution mechanism of SDC, which improved the model’s capture of temporal features, and the use of GAN, which effectively reduced background noise interference and enhanced the prediction accuracy of vibration signal trends.

Analysis of bearing fault detection performance

After verifying the feature extraction effectiveness, the model’s application in fault detection was evaluated using the CWRU dataset. Different models were compared in detecting fault types in different bearing components. The maximum sampling frequency was set to 5,000 Hz, and various fault types and corresponding bearing sizes were configured. The experimental parameters are shown in Table 1.

As shown in Table 1, four bearing fault types were defined: normal, inner race fault, outer race fault, and rolling element fault. Corresponding labels were assigned based on different fault sizes. The SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model was compared with other models for bearing fault classification performance under different combinations. The results are shown in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13a, the BPNN-UKF model incorrectly identified 7 samples among 500, including 3 inner faults, 2 outer faults, and 2 rolling element faults, resulting in an overall accuracy of 98.60%. Figure 13b shows that TCN-BiLSTM wrongly classified 8 samples, comprising 3 inner, 3 outer, and 2 rolling element faults, achieving an accuracy of 98.40%. Figure 13c indicates that VMD-KELM misidentified 7 samples, including 1 normal sample, 1 inner fault, 2 outer faults, and 4 rolling element faults, with an accuracy of 98.60%. Figure 13d demonstrates that SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU only incorrectly labeled 2 samples, one outer fault as a rolling element fault and one rolling element fault as an inner fault, achieving an accuracy of 99.60%. These results indicated that the proposed model effectively distinguished different fault types with high classification accuracy. To further illustrate the performance, t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) was applied for feature visualization, and the results are presented in Fig. 14.

In Fig. 14a, in the input layer, the original vibration signal samples were randomly distributed with no clear separation. Figure 14b shows that in the dilated convolution part of the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model, normal signal samples were largely separated, with 4 samples still misclassified. Figure 14c shows that after noise smoothing and feature refinement in the model, the BiGRU module distinguished the key features of bearing vibration signals. Figure 14d illustrates that after BiGRU and GATv2 processing, the output signals were distinctly classified into normal condition, inner race, outer race, and rolling element faults, with just one outer race fault incorrectly identified as a rolling element fault and one rolling element fault incorrectly identified as an inner race fault. Repeated validation indicated that the SDC-Shuffle-BiGRU model achieved an overall fault detection accuracy of 99.62%. Overall, the proposed model demonstrated accurate and stable feature capture, enabling precise detection of bearing faults under complex vibration conditions.

To test the effectiveness of each improved module of the proposed method in the research, an ablation experiment was designed to delete or replace each module, and then analyze the performance of the model containing different modules. The selection modules include SDC (Module 1), ResNet (Module 2), CBAM (Module 3), GAN (Module 4), and Shuffle algorithm (Module 5). The basic model is the GAT-BiGRU model. The comparison indicators include response time and diagnostic accuracy. The results are shown in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, with the gradual introduction of each module, the diagnostic accuracy of the model shows a significant upward trend, while the response time continues to decline. When adding any single module alone, the performance improvement is limited. However, under the collaborative effect of multiple modules, especially after the combination of SDC and Shufflet-BigRU, the feature extraction ability is significantly enhanced. The complete model of Group 17 performed the best among all configurations, with an accuracy rate of 96.42% and a response time reduced to 0.85 s, verifying the necessity and collaborative effectiveness of each improved module.

The research verified the equipment operation data of the entire year of 2024 in the industrial park of Location A, covering a total of 876 key equipment of 12 types. The sampling frequency was 10 s per time, and the total data volume reached 215,258 entries. The comparison models include BPNN-UKF, TDN-BILSTM, and VMD-KELM. The comparison results of diagnostic accuracy, R2, and MAE indicators of several models on different device types are shown in Table 3.

As shown in Table 3, the DCC-Shufflet-BIGRU model proposed in the study significantly outperforms the comparison models in all indicators, especially in terms of accuracy and MAE. Compared with the suboptimal model TCN-BiLSTM, it has increased by 6.3 percentage points and reduced the average absolute error by 0.06 respectively. The R2 value reached 0.931, indicating that the model has a stronger fitting ability for the equipment status and the diagnostic results are more stable and reliable. Under complex working conditions, this model can still maintain high robustness, verifying its application potential in actual industrial scenarios.

To explore its feasibility on other device systems, the SDC-Shufflet-BigRU model was lightweight and deployed on the NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX edge computing platform in the study. The measured power consumption was only 12.3 W, and the inference speed reached 117 frames per second, meeting the real-time requirements. During the continuous 72-h stress test, the model operated stably without downtime, with the average response time fluctuating within less than ± 0.05 s and the peak memory usage not exceeding 4.2 GB, confirming its high efficiency and reliability in resource-constrained environments. In the actual production line deployment, the model was successfully integrated into the intelligent operation and maintenance platform of the A location park, achieving early warning of key equipment failures. The average fault identification time was reduced to 8.7 s, an improvement of over 60% compared to traditional methods. The system processes over 200,000 data entries on average each day, with a false alarm rate controlled within 1.3%, significantly reducing the burden of manual re-checks.

Conclusions and recommendations

To address the challenges of high complexity in feature extraction and low fault detection accuracy under complex working conditions, a bearing fault detection model combining SDC and Shuffle was proposed. The model used GAN’s generator and discriminator to identify key features and combined BiGRU and GATv2 for fault recognition, effectively enhancing robustness under strong noise interference. In the testing experiments, the model achieved a sample classification prediction accuracy of 97.88%, an F1 score of 0.9102, an average inference speed of 274 fps, and computational cost and parameter size of 1.66 FLOPs and 7.76 M, respectively, indicating that the model achieved high precision while maintaining lightweight computation. In the feature extraction experiments, the model achieved a fitting accuracy of 96.13% for bearing vibration signals, and the MAE and RMSE of amplitude acceleration prediction were 2.88 mm2/s and 5.12 mm2/s, respectively, confirming the model’s strong capability in bearing feature extraction. In the fault recognition tasks, the model achieved an overall fault detection accuracy of 99.62%, outperforming the comparison models and further confirming its excellent fault detection performance. Overall, although the proposed model demonstrated lightweight feature extraction and precise fault detection, the experiments did not consider the impact of bearing wear under complex working conditions. Future studies can combine the bearing’s service life to further enhance the model’s generalization capability.

The improvement of computing efficiency sacrifices the ability to capture some redundant features, which may affect the fault tolerance under extreme working conditions. Subsequent optimization needs to seek a better balance between lightweight and feature integrity, combining dynamic reasoning mechanisms with adaptive feature selection strategies to further enhance the model’s adaptability and stability in the ever-changing industrial environment. When the model is extended to fault diagnosis tasks of other types of rotating machinery, its migration ability and universality need to be further verified. For this reason, future work can consider conducting cross-domain adaptability experiments under different equipment operating conditions, and constructing a unified fault diagnosis framework covering multiple types of machinery such as gearboxes and motors. By introducing meta-learning and domain adaptation mechanisms, the model’s rapid generalization ability for unseen device types is enhanced.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Deveci, B. U., Celtikoglu, M., Albayrak, O., Unal, P. & Kirci, P. Transfer learning enabled bearing fault detection methods based on image representations of single-dimensional signals. Inf. Syst. Front. 26(4), 1345–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-023-10371-z (2024).

Kumar, R. & Anand, R. S. Bearing fault diagnosis using multiple feature selection algorithms with SVM. Prog. Artif. Intell. 13(2), 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13748-024-00324-1 (2024).

Zhang, J., Zhang, K., An, Y., Luo, H. & Yin, S. An integrated multitasking intelligent bearing fault diagnosis scheme based on representation learning under imbalanced sample condition. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 35(5), 6231–6242. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3232147 (2024).

Al Mamun, A. et al. Multi-channel sensor fusion for real-time bearing fault diagnosis by frequency-domain multilinear principal component analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 124(3), 1321–1334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-022-10525-4 (2023).

Mitra, S. & Koley, C. Early and intelligent bearing fault detection using adaptive superlets. IEEE Sens. J. 23(7), 7992–8000. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3245186 (2023).

Mishra, R. K., Choudhary, A., Fatima, S., Mohanty, A. R. & Panigrahi, B. K. A fault diagnosis approach based on 2D-vibration imaging for bearing faults. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 11(7), 3121–3134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42417-022-00735-1 (2023).

Dubey, R., Sharma, R. R., Upadhyay, A. & Pachori, R. B. Automated variational nonlinear chirp mode decomposition for bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 19(11), 10873–10882. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3229829 (2023).

Khawaja, A. U. et al. Optimizing bearing fault detection: CNN-LSTM with attentive TabNet for electric motor systems. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 141(3), 2399–2420. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2024.054257 (2024).

Simani, S., Lam, Y. P., Farsoni, S. & Castaldi, P. Dynamic neural network architecture design for predicting remaining useful life of dynamic processes. J. Data Sci. Intell. Syst. 2(3), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewJDSIS3202967 (2024).

Fang, H. et al. A lightweight transformer with strong robustness application in portable bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Sens. J. 23(9), 9649–9657. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3260469 (2023).

Wang, Z., Yang, Y. & Wu, F. A lightweight air quality monitoring method based on multiscale dilated convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 20(12), 14184–14192. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2024.3441653 (2024).

Dash, R., Rautray, R. & Dash, R. Utility of a shuffled differential evolution algorithm in designing of a Pi-Sigma neural network based predictor model. Appl. Comput. Informat. 19(1–2), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aci.2019.04.001 (2023).

Duan, Z. et al. QARV: Quantization-aware ResNet VAE for lossy image compression. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 46(1), 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2023.3322904 (2024).

Guo, Y., Mao, J. & Zhao, M. Rolling bearing fault diagnosis method based on attention CNN and BiLSTM network. Neural Process. Lett. 55(3), 3377–3410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11063-022-11013-2 (2023).

Malhotra, R. & Cherukuri, M. Convolutional neural networks for software defect categorization: An empirical validation. J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 31(1), 22–51. https://doi.org/10.3897/jucs.117185 (2025).

Liu, B., Ning, X., Ma, S. & Yang, Y. Dynamic feature distillation and pyramid split large kernel attention network for lightweight image super-resolution. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83(33), 79963–79984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-18501-8 (2024).

Sharma, P., Kumar, M., Sharma, H. K. & Biju, S. M. Generative adversarial networks (GANs): Introduction, taxonomy, variants, limitations, and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83(41), 88811–88858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-18767-y (2024).

Dubey, S. R. & Singh, S. K. Transformer-based generative adversarial networks in computer vision: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 5(10), 4851–4867. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAI.2024.3404910 (2024).

Rather, I. H. & Kumar, S. Generative adversarial network based synthetic data training model for lightweight convolutional neural networks. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83(2), 6249–6271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-15747-6 (2024).

Li, M., Peng, P., Zhang, J., Wang, H. & Shen, W. SCCAM: Supervised contrastive convolutional attention mechanism for ante-hoc interpretable fault diagnosis with limited fault samples. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35(5), 6194–6205. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2023.3313728 (2024).

Sun, K. et al. Joint Top-K sparsification and shuffle model for communication-privacy-accuracy tradeoffs in federated-learning-based IoV. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(11), 19721–19735. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2024.3370991 (2024).

Ge, Q. et al. Shuffle-RDSNet: A method for side-scan sonar image classification with residual dual-path shrinkage network. J. Supercomput. 80(14), 19947–19975. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-024-06227-1 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Remote sensing image classification method based on improved ShuffleNet convolutional neural network. Intell. Data Anal. 28(2), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.3233/IDA-227 (2024).

Huang, K. & Xu, Z. Lightweight video salient object detection via channel-shuffle enhanced multi-modal fusion network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83(1), 1025–1039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-15251-x (2024).

Wimmer, P., Mehnert, J. & Condurache, A. P. Dimensionality reduced training by pruning and freezing parts of a deep neural network: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56(12), 14257–14295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-023-10489-1 (2023).

Sharma, S., Lodhi, S. S. & Chandra, J. SCL-IKD: intermediate knowledge distillation via supervised contrastive representation learning. Appl. Intell. 53(23), 28520–28541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-023-05036-y (2023).

Xu, Z., Li, Y. F., Huang, H. Z., Deng, Z. & Huang, Z. A novel method based on CNN-BiGRU and AM model for bearing fault diagnosis. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 38(7), 3361–3369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-024-0610-2 (2024).

Eknath, K. G. & Diwakar, G. Prediction of remaining useful life of rolling bearing using hybrid DCNN-BiGRU model. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 11(3), 997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-023-10135-6 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. A multisensory time-frequency features fusion method for rotating machinery fault diagnosis under nonstationary case. J. Intell. Manuf. 35(7), 3197–3217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10845-023-02198-x (2024).

Kim, C. S., Kim, H. B. & Min Lee, J. Self-explanatory fault diagnosis framework for industrial processes using graph attention. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 21(4), 3396–3405. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2025.3526708 (2025).

Li, D., Zhang, H., An, L., Dong, J. & Peng, K. A quality-related fault detection method based on deep spatial-temporal networks and canonical variable analysis for industrial processes. IEEE Sens. J. 24(18), 29047–29055. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3435013 (2024).

Funding

The research is supported by: Jiangsu Province, Universities’ Basic Science (Natural Science) Research Major Project (No. 24KJA510001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F.P. processed the numerical attribute linear programming of communication big data, and the mutual information feature quantity of communication big data numerical attribute was extracted by the cloud extended distributed feature fitting method. X.J.L. Combined with fuzzy C-means clustering and linear regression analysis, the statistical analysis of big data numerical attribute feature information was carried out, and the associated attribute sample set of communication big data numerical attribute cloud grid distribution was constructed. Y.F.P. and X.J.L. did the experiments, recorded data, and created manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, Y., Li, X. Bearing fault detection with lightweight feature extraction mechanism based on smoothed dilated convolution. Sci Rep 16, 2153 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31960-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31960-9