Abstract

Despite the success of speech separation approaches for dry (non-reverb) speech mixtures, speech separation in naturalistic, spatial, and reverberant acoustic environments remains challenging. This limits the effectiveness of current speech separation methods for assistive hearing devices as well as neuroprosthetic devices such as cochlear implants (CIs). Here, we investigate whether a deep neural network model for speech separation can utilize the spatial information in naturalistic listening scenes as captured by a CI’s microphones to improve separation performance. We examined the impact of latent spatial cues (inherently present in two-channel speech mixtures, but need to be learned from these mixtures), as well as pre-computed spatial cues added to the speech mixtures as auxiliary input features (inter-channel level and phase differences, ILDs and IPDs). Specifically, we introduce a two-channel version of the SuDoRM-RF speech separation model, which takes as input speech mixtures recorded with two CI microphones and shows that latent spatial cues enhance separation performance without affecting model efficiency in terms of model complexity and inference latency. Pre-computed spatial cues – especially IPDs – enhanced separation performance even more, but simultaneously reduced model efficiency. Finally, simulating a CI user’s listening experience with a vocoder showed that the beneficial effect of spatial cues on DNN speech separation persists even if the separated speech streams are spectrotemporally degraded as in the output of a CI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hearing impairments affect over 5% of the global population and result in significant communication challenges, even with the help of assistive hearing devices or cochlear implants (CIs)1,2. With over a million users worldwide3, CIs help to restore hearing for individuals with severe-to-profound hearing loss by directly stimulating the auditory nerve4,5. While they enable speech perception in quiet settings, CI users continue to struggle in noisy environments, such as classrooms, offices, and social gatherings6,7,8,9. These difficulties stem from both peripheral processing deficits, which hinder selective attention to a target speaker9, and the low spectral and temporal resolution of CI output5.

CI users’ performance in noisy listening scenes can be improved by enhancing front-end processing in the speech processor10. Traditional front-end approaches for noise removal in CIs include Wiener filtering (e.g.11) and beamforming10,12,13,14. With the rise of deep learning, these techniques are increasingly replaced by neural network approaches (e.g.,15,16,17), leading to substantial speech-in-noise perception gains for CI users18,19. In addition to these strategies for noise removal, using automatic speech separation algorithms as a front-end processing step has strong potential to further resolve the complex everyday listening scenes which typically contain multiple, overlapping talkers besides other noise sources20,21,22.

Developments in the field of automatic speech separation have advanced rapidly over the past decade. Starting from approaches operating in the time-frequency domain15,23,24,25,26,27,28, attention has shifted in recent years towards time domain approaches21,22,29,30,31. The latter avoid artifacts resulting from the phase inversion problem20,32,33, improve computational efficiency and reduce latency21,22,31. However, although automatic speech separation approaches have been shown to be highly successful when separating talker mixtures in clean environments without reverberation or spatial dimension, recent work shows that separation performance drops significantly in complex, acoustic environments34,35,36.

One strategy to enhance separation performance in such settings is to use multi-channel speech mixtures rather than single-channel speech mixtures. That is, by using multi-channel speech mixtures, the spatial information that is inherently present in naturalistic acoustic scenes can be utilized to boost speech separation. For example, several studies have extracted spatial features such as inter-channel phase differences (IPDs,33,37,38,39), time differences (ITDs,40), level differences (ILDs,40,41) and angle features (AF,33,37) from multi-channel sound mixtures a priori and added these as auxiliary input to the deep learning model.

However, while these studies show improved separation performance, their applicability for devices such as CIs, with strong constraints in terms of latency and computational efficiency, is unclear. In particular, most spatial speech separation approaches calculate spatial features from spectrogram representations of a talker mixture, even if the subsequent deep neural network model separating the two speech streams operates in the time domain (e.g.,39). The required short term Fourier transform introduces a significant increase in latency21. Further, by including spatial cues as auxiliary features, the number of parameters increases, leading to longer latencies and decreased computational efficiency33. Finally, to what extent the improvements in separation performance that emerge from explicitly incorporating spatial cues correspond to speech perception enhancement for CI users has, to the best of our knowledge, not been investigated.

We therefore investigated the effect of latent spatial cues and of pre-computed spatial cues on speech separation performance in naturalistic acoustic scenes for CI users. Here we refer to latent spatial cues as cues that are inherently present in multi-channel speech mixtures in the form of differences between the channels, but that need to be learned by the model. For example, as a CI has multiple microphones, the CI’s multi-channel microphone recordings contain latent spatial cues in the form of inter-channel differences. In contrast, pre-computed spatial cues refer to spatial cues - here, inter-channel level differences (ILDs) and inter-channel phase differences (IPDs) - that are extracted a priori from the multi-channel speech mixtures and added to the speech mixture as auxiliary feature. For these experiments, we adapted the SuDoRM-RF model, a highly efficient time-domain approach with state-of-the-art speech separation performance22, to accommodate two-channel input and auxiliary spatial features. As CIs require computationally efficient and low-latency approaches, we additionally quantified the impact of latent spatial cues and auxiliary, pre-computed spatial cues on computational efficiency and inference time. Finally, simulating the CI listening experience with a vocoder model,we assessed to what degree the performance of the proposed spatial speech separation approach with SuDoRM-RF extends to improved speech separation in the listening experience of CI users.

We show that in naturalistic acoustic scenes, the SuDoRM-RF speech separation model leverages latent spatial cues in naturalistic two-channel mixtures to improve speech separation performance. Importantly, learning from latent spatial cues is computationally efficient as it does not increase model complexity and inference time. Although adding pre-computed spatial cues such as IPDs and ILDs as auxiliary features to the two-talker mixtures improved speech separation performance of the SuDoRM-RF model even more than the presence of latent spatial cues, we found that adding these pre-computed spatial cues substantially reduces model efficiency by increasing model complexity and inference time. Of the two pre-computed spatial cues considered here, IPDs enhanced speech separation performance more than ILDs or the combination of IPDs and ILDs. In general, spatial cues - either latent or pre-computed - enhanced speech separation performance especially for speech mixtures with ambiguous spectral cues, that is, speech mixtures consisting of two talkers of the same gender (for example, female-female or male-male). Finally, we simulated the CI listening experience for our proposed spatial speech separation approach by applying a vocoder model to the separated speech streams. This showed that the improvements in speech separation resulting from leveraging spatial cues are robust to the spectrotemporal degradation of the separated speech streams by the CI. This suggests that CI users may also benefit from incorporating spatial cues in the speech separation pipeline in naturalistic acoustic scenes.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: section “Speech separation in naturalistic acoustic scenes” describes the task of speech separation, the generation of the naturalistic spatialized dataset, the model architecture, and the experimental framework for this study. In the section “Results”, we present the results and analysis. The section “Discussion” discusses the implications of our findings for speech enhancement in naturalistic listening scenes and CIs in particular.

Speech separation in naturalistic acoustic scenes

Task

In this study, the task of speech separation consists of estimating the waveform of talkers \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) from the waveform of the speech mixture y \(\in \mathbb {R}^{C \times T}\). Here, C represents the number of channels (i.e., microphones) and T denotes time.

Datasets

We generated a new, large dataset consisting of multi-channel, two-talker speech mixtures in naturalistic, spatial and reverberant listening scenes to train and evaluate the speech separation models. To generate this new dataset, we used the speech mixtures of the WSJ0-2mix dataset42, a CI head-related impulse response (HRIR) dataset, and a custom sound spatialization pipeline. The newly generated dataset of naturalistic two-talker speech mixtures is available in https://github.com/sayo20/Leveraging-Spatial-Cues-from-Cochlear-Implant-Microphones-to-Efficiently-Enhance-Speech-Separation-.

The two-talker speech mixtures in the WSJ0-2 dataset are widely employed for speech separation tasks21,29,30. The dataset is split into 20,000 speech mixtures for training, 5000 speech mixtures for validation and 3000 speech mixtures for testing42. The CI HRIR dataset utilized here was a non-public dataset provided by Advanced Bionics (www.advancedbionics.com). HRIRs capture listener-specific acoustic properties and spatial characteristics. That is, the HRIR reflects the impact of the pinnae (outer ears), head, and torso on sound waves arriving at the ear canal43. The HRIR dataset provided by Advanced Bionics was measured by fitting a KEMAR mannequin44 with bilateral CIs. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, each CI has three microphones: A T-microphone situated at the entrance to the ear channel and two behind-the-ear microphones (front microphone and back microphone). In total, the Advanced Bionics CI HRIR dataset contained six HRIRs (corresponding to the six microphones) for each of 24 azimuth locations (from 0\(^{\circ }\) to 345\(^{\circ }\) in 15\(^{\circ }\) increments) at 0\(^{\circ }\) elevation (radius = 1.4 m). These CI-specific HRIRs (see below) enabled us to generate ecologically valid naturalistic listening scenes capturing the listening characteristics of CI users.

A Schematic depiction of generation of naturalistic two-talker speech clips. CI-HRIR Cochlear implants Head-related Impulse Response, RIR Room impulse response, BRIR Binaural Room Impulse Response, SDM spatial decomposition method. B An acoustic scene depicting talkers positioned around a listener located in a room. C Schematic example of an acoustic scene with two talkers and a listener wearing bilateral CIs. Each CI has three microphones: F front microphone, B back microphone, T T-microphone.

Spatialization pipeline

Our custom spatialization pipeline is depicted in Figure 1 and consisted of three components described in detail below: (1) Simulating room impulse responses (RIRs), (2) Simulating binaural room impulse responses (BRIRs); and finally (3) Generating naturalistic, multi-channel two-talker mixtures.

Simulating room impulse responses (RIRs)

A RIR describes room-specific acoustic properties including direct sound, early reflection, and reverberation. Here, we used the Pyroomacoustics Python package45, which employs an image source model to efficiently simulate RIRs by simulating sound wave propagation from a source to a receiver within a shoebox room. In total, we simulated 500 shoebox rooms with different dimensions and reverberation properties (Fig. 1B). Room dimensions were randomly selected from a range of \(4 \times 4 \times 2.5\) m to \(10 \times 10 \times 5\) m (length \(\times\) width \(\times\) height), encompassing common sizes of classrooms, meeting rooms, and restaurants46.

For each RIR, we sampled reverberation time (\(T_{60}\)) from a range of 0.2–0.7 s (step size = 0.01 s). Reverberation time reflects the strength of reverberation in a room and is dependent both on the size of the room and the materials of which the room consists47,48. To introduce a naturalistic relation between room size and \(T_{60}\), we restricted the range of \(T_{60}\) to sample from based on room size. That is, we used the total volume of each room as an index to sample from the range of \(T_{60}\) where the smallest room volume corresponded to the \(T_{60}\) = 0.2 s and the largest room volume to \(T_{60}\) = 0.7 s. To increase variability, random jitter of \(\pm {0.01}\) s was added. This resulted in a single \(T_{60}\) value per room, selected to match its relative size (see Fig. 2A).

A Reverberation time (\(T_{60}\)) as a function of room size. Each circle represents a single room. B Effect of reverberation and spatialization on speech mixtures. Top panes show waveforms of a dry, non-spatial speech mixture and a spatial, reverberant version of the same speech mixture. For illustration, bottom panes depict spectrograms (but note that models are trained directly on the waveform). Amp. = amplitude; a.u. = arbitrary units. C Presence of latent spatial cues in naturalistic acoustic scenes. Top pane shows an example of a two-talker mixture in a spatial, reverberant scene. One talker is at -90\(^{\circ }\), the other talker is at +90\(^{\circ }\). Bottom pane visualizes the corresponding inter-channel level differences for this speech mixture from the T-mic of the left CI and the T-mic of the right CI.

To define the position of a listener within the room, we positioned a grid of potential listener locations (that is, receiver locations) in the room (Fig. 1B). The grid consisted of listener positions spaced 1 m apart and was centered within the room with axes aligned parallel to the walls. The grid was positioned at a minimal distance of 1.4 m from all walls in agreement with the CI-HRIR radius of 1.4 m (see the section “Datasets”). For each room, we randomly selected five distinct listener positions from this grid, resulting in five RIRs corresponding to five listener positions per room. Note that the smallest rooms permitted only four listener locations. To define the position of the talkers (i.e., the sources) with respect to the listener, we positioned a circle (radius = 1.4 m) around each selected listener location. On this circle, we simulated 24 talker (source) locations in the azimuthal plane in equidistant steps of 15\(^{\circ }\), in agreement with the 24 azimuth locations that were included in the CI HRIRs. Both talker locations and listener locations were positioned at a height of 1.25 m, simulating the seated position of the listener and talkers. This procedure led to the generation of a total of 59,688 RIRs \(500 \text { rooms} \times \sim 5 \text { listener positions} \times 24 \text { talker positions}\)

Note that we simulated all RIRs used in this study for a virtual microphone geometry consisting of six DPA-4060 omnidirectional microphones arranged in orthogonal pairs (diameter = 10 cm), and a central Earthworks M30/M50 omnidirectional microphone45. This microphone geometry was selected for the RIR simulations to ensure compatibility with the spatial decomposition (SDM) method used in the next step of the spatialization pipeline (BRIR generation; the section “Spatialization pipeline”; Binaural Room Impulse Response), as SDM is suitable only for particular RIR microphone geometries49.

Simulating binaural room impulse responses (BRIRs)

The BRIR combines the room-specific acoustic properties (i.e., the RIR) with the listener-specific acoustic properties (i.e., the CI-HRIR)50. Convolving a single-channel, dry speech mixture with a BRIR thus results in a naturalistic, spatialized and reverberant speech mixture that captures both room-specific and listener-specific acoustic properties. To generate BRIRs from our set of RIRs and the CI-HRIRs, we leveraged the BRIR generator proposed by Amengual et al.49 which uses the spatial decomposition method (SDM) proposed in51. Here, SDM is used to extract directional information about the direct sound, early reflections and late reverberations, which is then combined with the HRIRs to render realistic BRIRs with a clear spatial percept51.

We selected the T-microphone CI HRIRs of the left and right ear from the Advanced Bionics CI HRIR dataset as our main microphones for these two-channel, bilateral BRIR simulations, because the T-microphone52 is considered less susceptible to environmental noise53 than BTE microphones such as the front and back microphone54,55. We additionally generated BRIRs using the back-microphone CI HRIRs. These back-microphone BRIRs were utilized in two settings: (1) To generate unilateral, two-channel speech mixtures by combining a T-microphone and a back-microphone HRIR from the same CI; (2) To evaluate generalization of speech separation in naturalistic listening scenes across CI microphones (see below).

Generating naturalistic, two-channel two-talker speech mixtures

We simulated naturalistic, two-talker speech mixtures with varying separation angles between talkers: 0°, 15°, 30°, 60°, and 90°, corresponding to 19.9%, 19.98%, 19.81%, 20.14%, and 20.18% of the total dataset, respectively. To construct these mixtures, we combined clean speech segments from the publicly available WSJ0-2mix dataset42, CI-specific HRIRs provided by Advanced Bionics, and room impulse responses (RIRs) that we simulated as part of this study. To this end, we convolved the single-channel waveform of each talker selected for the two-talker mixture (i.e., selected from the WSJ0 dataset) with the a priori generated BRIR corresponding to a given acoustic room and talker location. The BRIRs were generated by combining our simulated RIRs with the CI-HRIRs to produce listener- and room-specific spatial audio. We then summed the spatialized and reverberant waveforms of both talkers to render the two-talker speech mixtures (see Fig. 2B). All audio clips of two-talker mixtures were cut to a duration of four seconds. Shorter speech mixtures were zero-padded either at the beginning or end (randomized to avoid systematic alignment of talker onset). The resulting mixtures were mean-variance normalized and downsampled to 8 kHz.

To evaluate whether the naturalistic, spatialized two-talker mixtures contain realistic spatial cues, we calculated ILDs from T-microphone recordings of the left ear and T-microphone recordings of the right ear. Figure 2C shows the ILDs for an example two-talker mixture in which one talker is at the left of the listener and one talker is at the right of the listener. ILDs fall within expected range based on the anatomy of the human head and ears56.

Model

In this study, we adapted the SuDoRM-RF model22 to evaluate the impact of latent and pre-computed spatial cues on speech separation performance ( Fig. 3). The SudoRM-RF model is highly efficient in terms of computation and memory22, crucial characteristics for models intended to operate on compact devices like CIs57.

SuDoRM-RF is an end-to-end time-domain model that consists of an encoder-decoder architecture with three stages: an encoder, a separator, and a decoder. For a comprehensive understanding of these stages, refer to22. In short, the encoder processes the two-talker mixture waveform y through a Conv1D block, generating a latent representation (\(R_l\)) of the mixture. Subsequently, the separator block (consisting of a U-net architecture) learns masks (M) for each talker present in y. The learned masks are multiplied with the latent representation of the mixture (\(M \times R_l\)) to extract a latent representation of each talker. Finally, the decoder block converts the estimated talker’s representations back into a speech sound wave22.

In the original implementation, SuDoRM-RF,22 was used for single-channel speech separation. We adapted the SuDoRM-RF model to accommodate two-channel speech mixtures by changing the kernel size of the encoder’s first 1D convolutional layer from \((1 \times T)\) to \((2 \times T)\), where T denotes time steps (Fig. 3A, top panel). The rest of the architecture remained unchanged. In particular, we utilized the following SuDoRM-RF configuration (based on the original configuration22): An encoder with 512 basis functions and a kernel size of T = 21, corresponding to 2.63 ms. The U-net architecture consisted of 16 U-convolutional blocks, which were set to 128 output channels with up-sampling depth = 4. Further, the model utilizes global layer normalization (gLN).

Finally, in case pre-computed spatial cues - that is, IPDs and/or ILDs - were added as auxiliary features for model training (see the section “Experimental procedures” for details on spatial cue extraction), these were concatenated with the latent representation of the two-channel mixture waveform obtained with the encoder module. The concatenated latent representation and spatial features were then fed into the separator module such that the separator could utilize both the latent representation and spatial cues during mask estimation (Fig. 3B, bottom panel). This increased the dimension of the input to the separator from 512 × 3200 to 769 × 3200 when either IPDs or ILDs were added, and to 1026 × 3200 in case both IPDs and ILDs were added. All other parameters of the separator module remained the same. All code available at https://github.com/sayo20/Leveraging-Spatial-Cues-from-Cochlear-Implant-Microphones-to-Efficiently-Enhance-Speech-Separation-.

Experimental procedures

Latent and pre-computed spatial cues

As stated previously, we define latent spatial cues as cues that are inherently present in multi-channel speech mixtures, but that need to be identified and learned by the model from these multi-channel speech mixtures. For example, as a CI has multiple microphones, a CI’s multi-channel recordings of an acoustic scene contain inter-channel differences that can be identified and learned by a model. In contrast, pre-computed spatial cues are cues that are calculated a priori and added to the speech mixture as auxiliary feature. In the present study, we consider inter-channel phase differences (IPDs) and inter-channel level differences (ILDs). To extract these cues, we first converted waveforms to the time-frequency domain using the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT; hop size = 8 s, number of frequency bins = 512, and window length = 512 samples). We then calculated IPDs and ILDs from the spectrogram representations of each channel in the two-channel speech mixture (\(y_{c1}\), \(y_{c2}\)) in the following manner:

Spatial speech separation with a two-channel SuDoRM-RF22 architecture. To evaluate the impact of spatial cues on speech separation performance, we trained eight instances of the SuDoRM-RF model. Instances vary in terms of CI microphone channels selected for training as well as the addition of auxiliary pre-computed spatial cues (Table 1). All models trained on two-channel speech mixture input only followed the model architecture depicted in the top row (A), while all models trained on two-channel speech mixture input augmented with pre-computed spatial cues followed the architecture depicted in the bottom row (B). The example shows the calculated IPDs (range [–180, 180] degrees). Training parameters were the same for all model instances.

Model input configurations

In total, we trained eight instances of the SuDoRM-RF model, one for each model input configuration (Table 1). Model input configurations varied in terms of number of channels in the speech mixture (that is, number of CI microphones), CI microphone and microphone location, presence of latent spatial cues, and addition of pre-computed spatial cues. The strength of both latent and pre-computed spatial cues is determined mostly by the location of the CI microphones used for generating the speech mixtures: Bilateral two-channel configurations with microphones on each side of the head contain stronger spatial cues than unilateral two-channel configurations with microphones on one side of the head only. That is, the position of the head in between the two channels in bilateral set-ups introduces the strongest inter-channel differences (Table 1).

Training objective

To train the network in an end-to-end manner, we utilized the negative scale-invariant signal-to-distortion ratio (SI-SDR)58 as learning objective:

Where \(t_{target}\) is the true reverberant target and \(e_{noise}\) is the difference between the estimated target and the true reverberant target (\(s_{target}\) - \(t_{target}\)). We used the reverberant true target to enable the model to focus on the task of separation rather than both separation and de-reverberation. In order to maximize SI-SDR in the separated speech streams the model is optimized using the negative SI-SDR loss. This encourages the model to produce estimates that are increasingly closer to the reference signals, thereby improving separation quality. Further, we used permutation-invariant training (PIT)59 to resolve the permutation problem.

Model training and evaluation

To train and evaluate models, we followed the original split of the WSJ0-2 corpus42 consisting of 20,000 train samples, 5000 validation samples and 3000 test samples. However, while the speech mixtures of the WSJ0-2 corpus are fixed talker pairings, we increased the diversity in the dataset by randomly shuffling talkers within each batch to generate new talker mixtures. Talker shuffling was applied solely to the train set, but not to the validation and test set.

We trained an independent model for each input configuration, resulting in a total of seven trained SuDoRM-RF speech separation models corresponding to the seven input configurations (Fig. 3B). Models were implemented using the Pytorch framework60 and trained for a minimum of 100 epochs (batch size = 4), after which early stopping was applied based on the validation loss (patience = 10, minimum delta = 0.1). We used the Adam optimizer61 and a learning rate of \(10^{-3}\) with a decay of 0.2 every 50 epochs. After model training completed, we utilized the network weights corresponding to the best epoch (lowest validation loss) to subsequently assess model performance on an independent test set.

Evaluation metrics

We employed the Scale-invariant Signal-to-Distortion Ratio (SI-SDR)58 and its improvement variant (SI-SDRi) as evaluation metrics to assess the performance of the model. The SI-SDRi quantifies the increase in SI-SDR in the cleaned speech waveforms in comparison to the initial two-talker mixture. Although the model was trained on the SI-SDR loss (see the section “Experimental procedures”), the SI-SDRi is more informative for comparing speech separation performance across different input configurations due to the differences in baseline SI-SDR between input configurations as a result of the spatialisation and reverberation. We calculated both distortion metrics using the Asteroid framework62. Additionally, we measured the perceptual quality of the cleaned speech segments using the Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI, range [0,1])63 and Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality (PESQ, range [–0.5, 4])64 metrics. Both perceptual metrics were derived using the Torchaudio Toolbox65. Finally, we report model efficiency in terms of the number of trainable parameters (in millions) and inference time (in milliseconds).

Zero-shot transfer to a behind-the-ear (BTE) microphone

As described above, naturalistic two-talker speech mixtures were spatialized with the HRIR of the T-microphone of the Advanced Bionics CI device, which is situated at the entrance of the ear canal. We conducted a zero-shot transfer test to assess to what extent speech separation performance of models trained on speech mixtures spatialized with T-microphone HRIRs, generalizes to mixtures spatialized with behind-the-ear microphones. To this end, we generated an additional version of the independent test set of the WSJ0-2 corpus (3,000 samples, see above) using the HRIR of the back microphone (Fig. 1C). We then evaluated speech separation performance of each trained SuDoRM-RF speech separation model on this back mic-version of the WSJ0-2 test set in a zero-shot setting. That is, the models were evaluated on the WSJ0-2 test set spatialized with the back-microphone HRIRs without seeing any mixtures spatialized with the back-microphone during training.

Generalization to CI listening experience

As the electrical stimulation of a CI replaces a sound wave with a sparse and spectrotemporally distorted representation of the original sound wave, a CI user’s listening experience deviates considerably from the listening experience of a normal hearing listener. Speech separation performance metrics based on the sound waves of the separated speech streams as produced by a speech separation model - such as the SI-SDR, STOI and PESQ metrics used here - may therefore not relate directly to improvements in listening experience for a CI user listening to a sparse, spectrotemporally degraded version of these separated speech streams. We therefore quantified the impact of the speech separation approaches proposed in the present paper on the listening experience of CI users. Specifically, we utilized a vocoder to simulate the degradation of the separated speech streams introduced by the CI and re-calculated speech separation performance metrics based on these CI listening simulations.

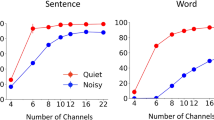

The vocoder utilized here was an eight-channel noise vocoder simulating the auditory processing of a cochlear implant66. Vocoder channels comprised eight frequency bands defined by center frequencies ranging from 366 Hz to 4662 Hz and corresponding bandwidths. To process sound waves with the vocoder, waveforms were first resampled to 22 kHz and pre-emphasized with a high-pass Butterworth filter (1.2 kHz cut-off). Next, bandpass filters were applied to isolate each channel and the signal in each band was rectified and low-pass filtered at 128 Hz to extract the envelope. To generate the CI output signal, Gaussian noise was generated for each channel and modulated by the extracted envelopes. The resulting modulated Gaussian noise signals were then bandpass filtered and summed across all channels to create the vocoded output. The output signal was normalized to maintain the same overall energy as the input.

To simulate CI listening experience, we passed the model’s output for the WSJ0-2 test set – that is, the separated speech streams – as well as the original two-talker mixtures and the true targets through a vocoder. We then re-calculated all speech separation performance metrics (SI-SDRi, STOIi and PESQ) for these simulations of the degraded CI listening experience.

Results

The present work aimed to quantify the impact of latent and pre-computed spatial cues captured by CI microphones on speech separation in naturalistic listening scenes. We therefore assessed and compared speech separation performance for eight different input configurations, which vary in the presence and strength of latent and pre-computed spatial cues (Fig. 3B and Table 2). Furthermore, we evaluated separation performance both on regular speech and on simulated CI output - that is, vocoded speech - in order to determine the effectiveness of the approach for real-world CI applications.

Speech separation performance as a function of spatial distance between talkers. Panels show the average SI-SDRi for a specific input configuration (Fig. 3B, Table 2). Colors reflect spatial cues in input: latent (blue) and a combination of latent and pre-computed (green; consistent with Fig. 3B). Error bars depict standard error of the mean (SEM). The gray dashed line represents the average SI-SDRi at 0\(^{\circ }\) separation (overlapping talkers). Asterisks indicate a significant difference to SI-SDRi at 0\(^{\circ }\) talker distance (p < 0.0001).

Baseline: speech separation for dry, non-spatial scenes

To establish a baseline, we first trained and evaluated the SudoRM-RF model on one-channel, dry and non-spatial two-talker mixtures (i.e., the original WSJ0-2mix dataset42). As outlined in Table 2 (row 1), the model obtained an SI-SDRi of 12.96 dB for this dataset, indicating that the model accurately separated two concurrent speech streams. Although other, larger speech separation models outperform the current SuDoRM-RF implementation on the WSJ0-2mix dataset21,67, we selected this small and efficient model as it can potentially be deployed on a CI. Moreover, we did not pre-process two-talker speech mixtures (for example, silence removal) even though this may boost separation performance, in order to ensure that sound scenes maintained their natural characteristics.

Speech separation in naturalistic acoustic scenes

We quantified to what extent speech separation performance of the SuDoRM-RF model deteriorated when the model was trained on one-channel, naturalistic speech mixtures. Results show that the overall quality of the resulting separated speech waveforms was substantially lower when the model was trained on one-channel, naturalistic two-talker mixtures (SI-SDRi = 7.24 dB, STOIi = 0.13, PESQi = 0.46) than when the model was trained on one-channel, non-spatial, dry two-talker mixtures (SI-SDRi = 12.96 dB, STOI = 0.23 and PESQ = 1.22; Table 2). The observed decline of 44.2 % in SI-SDRi demonstrates that a model which performs well on non-spatial, dry two-talker mixtures does not generalize to naturalistic, spatial, and reverberant acoustic scenes.

Effect of incorporating latent and pre-computed spatial cues

We examined how speech separation performance in naturalistic listening scenarios improved by incorporating latent and pre-computed spatial cues (Methods). Table 2 (rows 2–4) shows that incorporating strong latent spatial cues significantly improved speech separation performance. In particular, training the model on two-channel, bilateral input with strong latent spatial cues resulted in better separation performance than training the model on one-channel, unilateral input with weak spatial cues (improvements: +9.6 % SI-SDRi, +24.2 % STOIi, and +14.4 % PESQi). Similarly, training on two-channel, bilateral input outperformed training on two-channel, unilateral input with intermediate spatial cues, showing additional gains of +4.6 % SI-SDRi, +7.9 % STOIi. PESQi did not show an improvement (-0.6 %). Furthermore, training the model on two-channel speech mixtures containing latent spatial cues does not affect either the number of parameters or the inference time significantly (Table 2). These findings demonstrate that the SudoRM-RF model can efficiently leverage latent spatial cues in multi-channel speech mixtures to support speech separation in naturalistic listening scenes.

Adding pre-computed spatial cues such as IPDs and ILDs as auxiliary input features for the separation module further enhanced performance across all configurations, with varying degrees of improvement (Table 2, rows 5–8). Training the model on two-channel, bilateral speech mixtures with IPDs as auxiliary features (i.e., combining latent and pre-computed spatial cues) resulted in the best performance: 9.19 dB SI-SDRi, 0.19 STOIi and 0.75 PESQi. Adding ILD as an auxiliary feature had a comparatively much smaller impact on separation performance (Table 2, row 7). Speech separation performance was also higher when IPD alone was provided as auxiliary input in comparison to when both IPD and ILD were provided: +5.2 % SI-SDRi, +3.2 % STOIi, and +5.9 % PESQi. Thus, our results indicate that IPDs are a more effective cue for enhancing speech separation in naturalistic listening scenes than ILDs.

To obtain insight into why IPDs enhanced speech separation by the SuDoRM-RF model in naturalistic two-talker mixtures more than ILDs or the combination of IPDs and ILDs, we analyzed the occurrence of IPDs and ILDs in such naturalistic scenes. That is, we calculated IPDs and ILDs for a low-pass white noise (0-4 kHz) in a representative naturalistic scene (\(RT_{60}\) = 0.3) at five different locations (see Supplementary Materials S3 for details). This revealed that the presence of reverberation in a naturalistic scene attenuates both ILDs and IPDs, but introduces more variability and distortion in ILDs than IPDs (Supplementary Figure S3). Thus, IPDs were more consistent and informative in the naturalistic scenes in the present study than ILDs.

Finally, in terms of model efficiency we found that adding one pre-computed spatial cue as auxiliary feature to the input to the separator module - that is, either IPDs or ILDs - resulted in an increase of 25.0 % in inference time due to the STFT computations. Adding IPDs or ILDs as auxiliary feature also increased the number of model parameters by 46.2 % as a consequence of the increase in input dimensionality for the separator module. Adding both IPDs and ILDs simultaneously as auxiliary spatial further increased inference time with 60.7 % and the number of model parameters with 96.2 % (Table 2).

Speech separation performance as a function of talker gender pairing and spatial distance for various input configurations. Bars show average SI-SDRi across small (0° and 15°) and large (60° and 90°) talker distances. F–F two female talkers, M–M = two male talkers, F–M one male and one female talker. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between small and large distances (Kruskal–Wallis H tests, FDR corrected: *** = p < 0.0001).

Speech separation as a function of talker distance

Since our results demonstrate that input configurations including latent and/or pre-computed spatial cues result in better speech separation, we examined whether greater spatial distance between talkers led to improved speech separation. Table 3 shows that for all input configurations that include either latent or latent and pre-computed spatial cues, separation performance (SI-SDRi) varied as a function of talker distance (Kruskal-Wallis H tests, FDR corrected for multiple comparisons), see Fig. 4.

Interestingly, our findings show that incorporating spatial cues in the input not only enhances the separation of spatially distant talkers but also of spatially overlapping talkers. Comparing speech separation performance for speech mixtures with 0° talker distance revealed that input configurations incorporating IPD performed better on mixtures of spatially overlapping talkers than other input configurations. The other input configurations consist of single-channel speech mixtures, two-channel speech mixtures (without pre-computed spatial cues as auxiliary features), and two-channel speech mixtures with pre-computed ILDs added as auxiliary feature. In contrast, both the two-channel, unilateral IPD input (SI-SDRi = 7.48 dB) and the two-channel, bilateral IPD input (SI-SDRi = 7.93 dB; see Supplementary Materials S1) yielded higher performance. These findings indicate that incorporating IPDs into the input of speech separation models benefits separation even for spatially overlapping talkers.

Spectral and spatial cues for speech separation interact

Given that speech separation models trained on conventional, non-spatial and dry acoustic scenes primarily rely on spectral differences between talkers to separate speech streams69, we hypothesized that spatial cues are particularly beneficial for separating speech mixtures when talkers’ voices are spectrally similar, that is, when spectral cues are ambiguous. To test this, we examined the effect of spatial talker distance on speech separation performance as a function of talker gender pairing for those input configurations that showed an effect of talker distance (see Table 3, Fig. 4). The results show that the impact of spatial talker distance was largest for speech mixtures consisting of two female talkers (F-F), intermediate for mixtures consisting of two male talkers (M-M), and smallest for mixtures consisting of one male and one female talker (M-F; Fig. 5, Table 4). For example, for the two-channel, bilateral input configuration with IPD as auxiliary feature, the difference in speech separation performance between talkers at small spatial distances and at large spatial distances was 28.3 % for mixtures consisting of two female talkers, 18,1 % for mixtures consisting of two male talkers and 11,0 % for mixtures consisting of one male and one female talker. Thus, speech mixtures consisting of talkers of the same gender exhibited a larger benefit from talker distance than speech mixtures consisting of talkers of different genders. These findings indicate that spectral and spatial cues are complementary, with spatial cues compensating when spectral distinctions are limited.

Zero-shot transfer to behind-the-ear (BTE) microphones

We found that the SuDoRM-RF model trained on naturalistic two-talker mixtures spatialized with T-microphone HRIRs, performed comparable when tested in a zero-shot setting on mixtures spatialized with back-microphone HRIRs (Table 5). In particular, speech separation performance metrics were comparable for all input configurations, irrespective of which CI microphone was used for spatializing the naturalistic two-talker mixtures.

Generalization to CI listening experience

Table 6 shows that SI-SDRi for the simulations of CI listening experience - that is, the vocoded version of the separated speech streams (Methods) - ranged from 2.64 dB to 3.31 dB, depending on the model input configuration. Although these SI-SDRi were overall lower than the SI-SDRi for the regular version of the separated speech streams (Table 2), this is still a substantial improvement. Moreover, we found that the boost in speech separation performance that effects of incorporating spatial cues SI-SDRi was highest for the vocoded The results show that incorporating spatial cues into the input resulted in similar benefits for vocoded speech as for regular speech: SI-SDRi was largest for vocoded speech streams that were separated by a model trained on speech mixtures with strong latent and/or pre-computed spatial cues (Table 6, rows 4–8). Moreover, in agreement with the results for regular speech, SI-SDRi was largest for the vocoded output of the model trained on two-channel, bilateral speech mixtures with IPD added as an auxiliary feature. Figure 6 shows the results for this configuration. Finally, also for vocoded speech, we found that separation performance varied as a function of talker distance (Fig. 6A) and that spectral and spatial cues interact (Fig. 6B). Similarly to the performance on regular speech, speech separation for 0\(^{\circ }\) talker distance mixtures showed that IPD-based configurations outperformed others on spatially overlapping talkers (see Supplementary Materials S2). Note that we display the results for the STOIi metric rather than the SI-SDRi metric as STOI is less affected by distortions that are introduced by the vocoder but not dependent on separation performance58.

Speech separation scores for vocoded speech. A) Average STOIi as a function of talker distance for one input configuration (two-channel, bilateral, IPD). The dashed line indicates average STOIi at 0° (overlapping talkers). B Average STOIi as a function of gender pairing and talker distance for the same configuration. Bars represent average scores for small (0°, 15°) and large (60°, 90°) distances. F–F = two female talkers, M–M = two male talkers, M–F = one male and one female talker. Asterisks indicate significant differences between distances (Kruskal–Wallis H tests, FDR corrected): *** = p < 0.0001.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated to what extent latent and pre-computed spatial cues captured via cochlear implant (CI) microphones improve speech separation performance in naturalistic listening scenes, taking also model efficiency in terms of model parameters and inference latency into consideration. We first confirmed that a SuDoRM-RF speech separation model trained on dry, non-spatial mixtures does not generalize well to reverberant, spatialized acoustic environments (see also35,36,70). Next, we showed that training a SuDoRM-RF model on multi-channel naturalistic speech mixtures containing latent spatial cues improved speech separation performance in naturalistic listening scenes, while preserving model efficiency. Training a SuDoRM-RF on multi-channel naturalistic speech mixtures augmented with pre-computed spatial cues (IPDs and/or ILDs) resulted in even larger speech separation improvements, but at the cost of reduced model efficiency.

Although this work focused on the SuDoRM-RF model because of its low latency and high efficiency22, the spatial separation framework we explored is broadly applicable. Both latent and pre-computed spatial cues can be integrated into time-domain as well as time-frequency separation models33,38,71,72, making these findings relevant across a wide range of architectures. Moreover, we showed with a zero-shot transfer test that this multi-channel speech separation approach is robust to CI-microphone configuration: A model trained on speech mixtures spatialized with T-microphone HRIRs performed equally well on mixtures spatialized with back-microphone HRIRs. This indicates that the spatial and spectral cues that the model learns from the multi-channel speech mixtures generalize across CI microphones. Crucially, these results demonstrate that such a multi-channel SuDoRM-RF speech separation framework does require re-training or fine-tuning for each particular CI-microphone configuration: A trained model can be employed both for speech mixtures captured with a T-microphone and for speech mixtures captured with a behind-the-ear microphone, irrespective of whether the model was trained on speech mixtures spatialized with the HRIRs of that microphone.

Based on the analysis of IPDs and ILDs in naturalistic scenes with reverberation (Supplementary Materials S3), we posit that the finding that IPDs enhance speech separation performance in naturalistic two-talker speech mixtures more than ILDs or a combination of IPDs and ILDs can be explained by the difference in the impact of reverberation on IPDs and ILDs. First, as IPDs exhibit a stable pattern across sound locations despite the presence of reverberation, the SuDoRM-RF model can learn the association between IPDs and the latent representation of a two-talker speech mixture more easily than the association between the inconsistent pattern of ILDs across sound locations and the latent representation of the two-talker speech mixture. Second, as a consequence of the inconsistent pattern of ILDs, there is no consistent relationship between IPDs and ILDs. Hence, combining IPDs with ILDs does not result in a similar benefit for speech separation as providing IPDs in isolation as the lack of a consistent relationship between the two spatial features makes their combination more difficult to learn than the IPDs in isolation.

Interestingly, our findings demonstrated that spatial cues are especially beneficial for speech separation for speech mixtures consisting of talkers with spectrally similar voices (for example, same gender talkers). In particular, we observed the smallest benefit from spatial cues for M-F mixtures and the largest improvements for F-F and M-M mixtures, supporting the idea that spatial cues are especially helpful when spectral cues are limited. A similar effect of voice spectral similarity on speech perception difficulty in multi-talker scenes has been reported in human psychophysics studies73.

Crucially, simulating the listening experience of a CI user by applying a vocoder to the separated speech streams revealed that these spatial cues provided a similar benefit for vocoded speech as for non-vocoded speech. Notably, IPD-based models improved separation for both spatially distant and overlapping talkers, whereas latent spatial cues were more limited in handling overlapping sources. These patterns were also reflected in perceptual intelligibility metrics such as STOI and PESQ, further supporting the benefit of spatial cues for CI users, especially in acoustically complex conditions involving spectrally similar talkers.

Finally, while our modified model operates within a latency range that may support offline or near-real-time use, further optimization is needed to meet the strict delay constraints of real-time CI systems. Additionally, a key limitation of this study is that findings are based on simulated acoustic scenes and vocoded speech; future work should validate these results through behavioral testing with CI users. Finally, the use of idealized shoebox room models limits ecological realism, and extending this approach to more acoustically diverse environments remains an important direction for future work.

Conclusion

This study explored the potential of leveraging spatial cues derived from cochlear implant microphones for efficient speech separation in naturalistic acoustic scenes. Our results highlight that training DNN models on speech mixtures in ecologically valid listening scenes (i.e., including reverberation and spatial location) is crucial for the development of speech separation technology for real-world applications such as front-end speech processing in a CI or other assistive hearing device. Moreover, our findings demonstrate that strong latent spatial cues boost speech separation accuracy in naturalistic listening scenes without decreasing model efficiency. Yet, adding IPD as auxiliary feature boosts speech separation accuracy most and, strikingly, also improves separation of spatially overlapping talkers. These insights pave the way for the development of more efficient speech separation approaches for listeners using CIs or other assistive hearing devices in everyday, noisy listening situations.

Data availability

Data and code can be found on github here: https://github.com/sayo20/Leveraging-Spatial-Cues-from-Cochlear-Implant-Microphones-to-Efficiently-Enhance-Speech-Separation-

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Deafness and Hearing. (accessed 14 November 2022). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (2021).

Caldwell, A. & Nittrouer, S. Speech perception in noise by children with cochlear implants. J. Speech, Lang. Hearing Res. 56, 13–30 (2013).

Zeng, F.-G. Celebrating the one millionth cochlear implant. JASA Express Lett. 2, 077201 (2022).

Naples, J. G. & Ruckenstein, M. J. Cochlear implant. Otolaryngol. Clin. North America 53, 87–102 (2020).

Zeng, F.-G., Rebscher, S., Harrison, W., Sun, X. & Feng, H. Cochlear implants: system design, integration, and evaluation. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 1, 115–142 (2008).

Qin, M. K. & Oxenham, A. J. Effects of simulated cochlear-implant processing on speech reception in fluctuating maskers. J. Acoust. Soc. America 114, 446–454 (2003).

Stickney, G. S., Zeng, F.-G., Litovsky, R. & Assmann, P. Cochlear implant speech recognition with speech maskers. J. Acoust. Soc. America 116, 1081–1091 (2004).

Healy, E. W. & Yoho, S. E. Difficulty understanding speech in noise by the hearing impaired: Underlying causes and technological solutions. In 2016 38Th Annual International Conference Of The IEEE Engineering In Medicine And Biology Society (EMBC), 89–92 (IEEE, 2016).

Shinn-Cunningham, B. G. & Best, V. Selective attention in normal and impaired hearing. Trends Amplif. 12, 283–299 (2008).

Henry, F., Glavin, M. & Jones, E. Noise reduction in cochlear implant signal processing: A review and recent developments. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 16, 319–331 (2021).

Serizel, R., Moonen, M., Van Dijk, B. & Wouters, J. Low-rank approximation based multichannel wiener filter algorithms for noise reduction with application in cochlear implants. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech Lang. Process. 22, 785–799 (2014).

Doclo, S. & Moonen, M. Superdirective beamforming robust against microphone mismatch. IEEE Trans. Audio, Speech Lang. Process. 15, 617–631 (2007).

Jarrett, D. P., Habets, E. A. & Naylor, P. A. Theory and Applications of Spherical Microphone Array Processing Vol. 9 (Springer, 2017).

de Souza, L. M., Costa, M. H. & Borges, R. C. Envelope-based multichannel noise reduction for cochlear implant applications. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech Lang. Process. (2024).

Lu, X., Tsao, Y., Matsuda, S. & Hori, C. Speech enhancement based on deep denoising autoencoder. Interspeech 2013, 436–440 (2013).

Lai, Y.-H. et al. A deep denoising autoencoder approach to improving the intelligibility of vocoded speech in cochlear implant simulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 64, 1568–1578 (2016).

Goehring, T. et al. Speech enhancement based on neural networks improves speech intelligibility in noise for cochlear implant users. Hearing Res. 344, 183–194 (2017).

Gaultier, C. & Goehring, T. Recovering speech intelligibility with deep learning and multiple microphones in noisy-reverberant situations for people using cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. America 155, 3833–3847 (2024).

Borjigin, A., Kokkinakis, K., Bharadwaj, H. M. & Stohl, J. S. Deep learning restores speech intelligibility in multi-talker interference for cochlear implant users. Sci. Rep. 14, 13241 (2024).

Wang, D. & Chen, J. Supervised speech separation based on deep learning: An overview. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 26, 1702–1726 (2018).

Luo, Y. & Mesgarani, N. Conv-tasnet: Surpassing ideal time-frequency magnitude masking for speech separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 27, 1256–1266 (2019).

Tzinis, E., Wang, Z., Jiang, X. & Smaragdis, P. Compute and memory efficient universal sound source separation. Springer 94, 245–259 (2022).

Wang, Y., Narayanan, A. & Wang, D. On training targets for supervised speech separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 22, 1849–1858 (2014).

Liu, Y. & Wang, D. Divide and conquer: A deep casa approach to talker-independent monaural speaker separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 27, 2092–2102 (2019).

Liu, Y. & Wang, D. Causal deep casa for monaural talker-independent speaker separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 28, 2109–2118 (2020).

Williamson, D. S., Wang, Y. & Wang, D. Complex ratio masking for monaural speech separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 24, 483–492 (2015).

Narayanan, A. & Wang, D. Ideal ratio mask estimation using deep neural networks for robust speech recognition. In 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, 7092–7096 (IEEE, 2013).

Xu, Y., Du, J., Dai, L.-R. & Lee, C.-H. An experimental study on speech enhancement based on deep neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 21, 65–68 (2013).

Huang, P.-S., Kim, M., Hasegawa-Johnson, M. & Smaragdis, P. Deep learning for monaural speech separation. In 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 1562–1566 (IEEE, 2014).

Zhang, X.-L. & Wang, D. A deep ensemble learning method for monaural speech separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 24, 967–977 (2016).

Luo, Y., Chen, Z. & Yoshioka, T. Dual-path RNN: efficient long sequence modeling for time-domain single-channel speech separation. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 46–50 (IEEE, 2020).

Perraudin, N., Balazs, P. & Søndergaard, P. L. A fast griffin-lim algorithm. In 2013 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Signal Processing to Audio and Acoustics, 1–4 (IEEE, 2013).

Gu, R. et al. Neural spatial filter: Target speaker speech separation assisted with directional information. In Interspeech, 4290–4294 (2019).

Gu, R. & Zou, Y. Temporal-spatial neural filter: Direction informed end-to-end multi-channel target speech separation. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:2001.00391 (2020).

Maciejewski, M., Wichern, G., McQuinn, E. & Le Roux, J. Whamr!: Noisy and reverberant single-channel speech separation. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 696–700 (IEEE, 2020).

Zhao, S. et al. Mossformer2: Combining transformer and RNN-Free recurrent network for enhanced time-domain monaural speech separation. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:2312.11825 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Multi-channel overlapped speech recognition with location guided speech extraction network. In 2018 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), 558–565 (IEEE, 2018).

Wang, Z.-Q. & Wang, D. Combining spectral and spatial features for deep learning based blind speaker separation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 27, 457–468 (2018).

Gu, R. et al. Enhancing end-to-end multi-channel speech separation via spatial feature learning. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 7319–7323 (IEEE, 2020).

Zohourian, M. & Martin, R. Binaural speaker localization and separation based on a joint itd/ild model and head movement tracking. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 430–434 (IEEE, 2016).

Gu, R., Zhang, S.-X., Yu, M. & Yu, D. 3D spatial features for multi-channel target speech separation. In 2021 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU), 996–1002 (IEEE, 2021).

Hershey, J. R., Chen, Z., Le Roux, J. & Watanabe, S. Deep clustering: Discriminative embeddings for segmentation and separation. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal processing (ICASSP), 31–35 (IEEE, 2016).

Gardner, B. et al. Hrft measurements of a kemar dummy-head microphone. Vis. Model. Group, Media Lab. Mass. Inst. Technol. (1994).

Burkhard, M. & Sachs, R. Anthropometric manikin for acoustic research. J. Acoust. Soc. America 58, 214–222 (1975).

Scheibler, R., Bezzam, E. & Dokmanić, I. Pyroomacoustics: A python package for audio room simulation and array processing algorithms. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 351–355 (IEEE, 2018).

Commercial Acoustics. Reverberation time graphic. (accessed on June 5 2023). https://commercial-acoustics.com/reverberation-time-graphic/ (2023).

Larson Davis. Reverberation time in room acoustics. (accessed on June 5, 2023). http://www.larsondavis.com/learn/building-acoustics/Reverberation-Time-in-Room-Acoustics (2023).

Acoustic Frontiers. Understanding small room reverberation time measurements. (accessed on June 5, 2023). https://acousticfrontiers.com/blogs/articles/understanding-small-room-reverberation-time-measurements (2023).

Amengual Garí, S. V., Arend, J. M., Calamia, P. T. & Robinson, P. W. Optimizations of the spatial decomposition method for binaural reproduction. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 68, 959–976 (2021).

Garí, S. V. A., Brimijoin, W. O., Hassager, H. G. & Robinson, P. W. Flexible binaural resynthesis of room impulse responses for augmented reality research. In EAA Spatial Audio Signal Processing Symposium, 161–166 (2019).

Tervo, S., Pätynen, J., Kuusinen, A. & Lokki, T. Spatial decomposition method for room impulse responses. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 61, 17–28 (2013).

Bionics, A. T-mic microphone. (accessed January 31 2024). https://www.advancedbionics.com/nl/nl/home/solutions/accessories/t-mic.html.

Mayo, P. G. & Goupell, M. J. Acoustic factors affecting interaural level differences for cochlear-implant users. J. Acoust. Soc. America 147, EL357–EL362 (2020).

Jones, H. G., Kan, A. & Litovsky, R. Y. The effect of microphone placement on interaural level differences and sound localization across the horizontal plane in bilateral cochlear implant users. Ear Hear. 37, e341–e345 (2016).

Kolberg, E. R., Sheffield, S. W., Davis, T. J., Sunderhaus, L. W. & Gifford, R. H. Cochlear implant microphone location affects speech recognition in diffuse noise. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 26, 051–058 (2015).

Moore, B. C. An Introduction to the Psychology of Hearing (Brill, 2012).

Wasmann, J.-W.A. et al. Computational audiology: new approaches to advance hearing health care in the digital age. Ear Hear. 42, 1499–1507 (2021).

Le Roux, J., Wisdom, S., Erdogan, H. & Hershey, J. R. Sdr–half-baked or well done? In ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 626–630 (IEEE, 2019).

Yu, D., Kolbæk, M., Tan, Z.-H. & Jensen, J. Permutation invariant training of deep models for speaker-independent multi-talker speech separation. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 241–245 (IEEE, 2017).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (2019).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. ArXiv Preprint arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Pariente, M. et al. Asteroid: the PyTorch-based audio source separation toolkit for researchers (In Proc, Interspeech, 2020).

Taal, C. H., Hendriks, R. C., Heusdens, R. & Jensen, J. An algorithm for intelligibility prediction of time-frequency weighted noisy speech. IEEE Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 19, 2125–2136 (2011).

Rix, A. W., Beerends, J. G., Hollier, M. P. & Hekstra, A. P. Perceptual evaluation of speech quality (pesq)-a new method for speech quality assessment of telephone networks and codecs. In 2001 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. Proceedings (Cat. No. 01CH37221), vol. 2, 749–752 (IEEE, 2001).

Yang, Y.-Y. et al. Torchaudio: Building blocks for audio and speech processing. In ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 6982–6986 (IEEE, 2022).

Dorman, M. F., Loizou, P. C. & Rainey, D. Speech intelligibility as a function of the number of channels of stimulation for signal processors using sine-wave and noise-band outputs. J. Acoust. Soc. America 102, 2403–2411 (1997).

Subakan, C., Ravanelli, M., Cornell, S., Bronzi, M. & Zhong, J. Attention is all you need in speech separation. In ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 21–25 (IEEE, 2021).

Yoav, B. & Yosef, H. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. B (Methodol.) 57, 289–300 (1995).

Qian, Y.-M., Weng, C., Chang, X.-K., Wang, S. & Yu, D. Past review, current progress, and challenges ahead on the cocktail party problem. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 19, 40–63 (2018).

Han, C., Luo, Y. & Mesgarani, N. Real-time binaural speech separation with preserved spatial cues. In ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 6404–6408 (IEEE, 2020).

Zhang, X. & Wang, D. Deep learning based binaural speech separation in reverberant environments. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 25, 1075–1084 (2017).

Wang, Z.-Q. & Wang, D. On spatial features for supervised speech separation and its application to beamforming and robust asr. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 5709–5713 (IEEE, 2018).

Bronkhorst, A. W. The cocktail-party problem revisited: early processing and selection of multi-talker speech. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 77, 1465–1487 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Advanced Bionics for providing the CI-HRTFs.

Funding

This work is part of the INTENSE consortium, which has received funding from the NWO Cross-over Grant No. 17619.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H , M.G, and F.O conceived the experiment(s), F.O. conducted the experiment(s), and analysed the results. K.H , M.G, F.O, C.S, J.B, and J.F reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Olalere, F., Heijden, K.v., Stronks, H.C. et al. Leveraging spatial cues from cochlear implant microphones to efficiently enhance speech separation in naturalistic listening scenes. Sci Rep 16, 2255 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31999-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31999-8