Abstract

Sleep deprivation has a significant impact on health and quality of life, with approximately 30% of adults worldwide suffering from insomnia. Physical activity has been recognized as a promising non-pharmacological intervention method, but the daily association between sleep and physical activity has not been clarified because key factors such as circadian rhythms and activity times have not been considered. Therefore, this study analyzed physical activity by time of day and intensity, and divided participants into circadian rhythm groups to examine the impact of physical activity on sleep on the same day. The results showed that physical activity had a significant influence on sleep efficiency, achieving a high accuracy of 0.8 or higher across all groups. Additionally, through explainable artificial intelligence, the study identified differences in the effects of physical activity by time of day, revealing that low-intensity activity in the evening, 12–15 hours after waking, had the greatest impact across all groups. These findings could serve as an important foundation for developing personalized, non-pharmacological intervention strategies to improve sleep quality. This study demonstrates the potential of explainable machine learning approaches to elucidate the complex relationship between physical activity and sleep, and suggests practical applications for promoting sleep health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep is an essential physiological process for maintaining physical and mental health and improving quality of life1. Sleep deprivation increases the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, depression, and anxiety disorders2,3. In particular, insomnia affects approximately 30% of the global adult population and is a major cause of significantly reduced quality of life4,5. As a result, maintaining and improving sleep quality has become a critical public health issue6. Traditional pharmacological treatments for insomnia have limitations due to issues of tolerance and dependence, leading to increased attention on non-pharmacological interventions such as physical activity as an effective alternative7,8,9.

However, contrary to the common belief that higher levels of physical activity improve sleep quality, most studies analyzing the daily association between physical activity and sleep have reported that the effect of physical activity on sleep efficiency is small or statistically insignificant. For example, Mitchell et al. (2016) analyzed the relationship between physical activity and sleep parameters (total sleep time, sleep efficiency) and found no significant correlation10. Additionally, Atoui et al. (2021) reported in their systematic review and meta-analysis that the effects of physical activity on sleep efficiency and total sleep time were small and inconsistent across studies2. Atoui et al. (2021) identified differences in measurement tools and the lack of consideration for the temporal characteristics of physical activity as major limitations. Park et al. (2022) developed a machine learning-based sleep prediction model by combining physical activity and light exposure data, but did not evaluate how the duration and timing of physical activity interact with sleep efficiency, and the association was low11.

The blue dashed curve represents sleep pressure (process S), which increases during wakefulness and decreases during sleep, and the orange curve represents circadian rhythms (process C), which regulate the sleep-wake cycle. The gray shaded area represents optimal sleep duration, which occurs when high sleep pressure coincides with circadian rhythms that promote sleep onset. This figure illustrates the temporal alignment of sleep pressure and circadian rhythm, which is central to this study’s hypothesis about how the timing of physical activity affects sleep efficiency.

The limitations of previous studies lie in the fact that they did not sufficiently consider the Two Process Model (Fig. 1), which is the basic theory explaining sleep. The Two Process Model proposed by Borbély (1982) is a theoretical framework for sleep regulation that integrates two independent processes: sleep pressure (process S) and circadian rhythm (process C). This model was further refined by Dijk and Czeisler (1995)12,13. According to the Two Process Model, physical activity simultaneously influences sleep pressure (Process S) and circadian rhythms (Process C), and these two mechanisms play a crucial role in regulating sleep-wake cycles. Sleep pressure (Process S) gradually increases during wakefulness due to the accumulation of neurotransmitter metabolites that are depleted during sleep. Thus, daytime physical activity can regulate the rate and level of sleep pressure increase. Physical activity plays an important role in increasing energy expenditure, which in turn promotes the accumulation of adenosine, which strengthens sleep pressure13. Circadian rhythms (process C) are centered around the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and are regulated by external signals such as light. In particular, the acrophase, which represents changes in the phase of circadian rhythms, has a decisive influence on sleep quality and sleep onset timing14. Additionally, physical activity indirectly influences the circadian clock, adjusting the phase of the circadian rhythm and modulating melatonin secretion to regulate the onset of sleep13. However, previous studies may have underestimated the impact of physical activity on sleep, as they did not account for temporal aspects, remained focused on total activity volume, or failed to consider factors such as activity intensity. Therefore, this study approaches the two main mechanisms that affect sleep–sleep pressure (Process S) and circadian rhythm (Process C)–based on the Two Process Model, which is the basic theory of sleep regulation. Rather than simply analyzing the total amount of activity per day, we aim to evaluate the effect of physical activity on sleep efficiency by comprehensively considering the intensity of activity at different times of the day after waking up, grouped by circadian rhythm. Additionally, this study uses sleep efficiency as an objective indicator to evaluate sleep quality. Sleep efficiency is a relatively quantitative and reliable indicator that can compensate for the limitations of self-reported sleep assessments and is frequently used in sleep research15,16. Furthermore, sleep efficiency was clinically classified into two groups–a relatively good sleep group and a impaired sleep group–using an 85% threshold to indicate the possibility of insomnia17. Furthermore, XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) was applied to effectively detect nonlinear interactions between sleep and physical activity, and SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) analysis was used to analyze the effects of activity intensity variables on sleep efficiency. Through this, we aim to examine whether the generalized perception that simply moving more leads to better sleep is empirically valid, and further investigate how the influence of physical activity on sleep efficiency varies depending on the time of day or an individual’s circadian rhythm.

Methods

Dataset overview

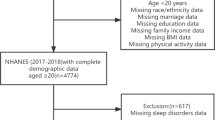

This study examined associations between physical activity and sleep efficiency using publicly available, de-identified data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Sleep ancillary study and the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL), collected between 2010 and 2013 under National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute support18,19,20,21. MESA enrolled 2,261 adults aged 45–84 years, and HCHS/SOL enrolled 2,252 adults aged 18–74 years. In the MESA Sleep ancillary cohort, participants were older adults (mean age approximately 68 years) with a slight predominance of women (around 54%), whereas in the HCHS/SOL Sueño ancillary cohort, participants were primarily middle-aged adults (mean age in the mid–40s) with women comprising roughly two-thirds of the sample. Despite these demographic differences, both cohorts span broad adult age ranges and include both men and women, and they used the same wrist-worn actigraph with harmonized accelerometry and sleep-assessment protocols. Therefore, combining participants from MESA and HCHS/SOL into a single analytic dataset is methodologically reasonable; to account for any residual between-study differences, all models additionally included an indicator variable for cohort (MESA, HCHS/SOL). For the present analysis, we included participants with at least seven valid days of actigraphy and excluded those with missing primary sleep questionnaire data or self-reported use of sleep medications or daytime naps. After applying these criteria, the analytic sample comprised \(N = 2{,}312\), as summarized in Table 1.

All data used in this study were de-identified and accessed from the MESA Sleep ancillary study and HCHS/SOL according to their respective data use agreements. Parent study protocols were approved by institutional review boards at Columbia University, Johns Hopkins Medicine, Northwestern University, UCLA OHRPP, the University of Minnesota, and Wake Forest Baptist Health (MESA), and at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, the University of Miami, the University of Illinois Chicago, San Diego State University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (coordinating center) (HCHS/SOL). All participants provided written informed consent, and all procedures complied with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, this secondary analysis of de-identified public data was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang University and was granted an exemption from further ethical oversight (approval No. 2025-11-004).

Actigraphy-based physical activity feature extraction

To analyze the effect of physical activity on sleep according to intensity, activity count data collected by wrist actigraphy were converted to 1-minute epochs and expressed as counts per minute (CPM)22. Based on the CPM cut-points shown in Table 1, each 1-minute epoch between wake onset and bedtime was classified into low-intensity (light physical activity, LPA), moderate-intensity (moderate physical activity, MPA), or high-intensity (vigorous physical activity, VPA). For each valid day, we then divided the post-wake period into 24 consecutive 1-hour bins aligned to the individual’s wake-up time (0–1 h, 1–2 h,..., 23–24 h after waking). Within each bin, we quantified the number of minutes spent in LPA, MPA, and VPA. Daily values were then aggregated at the participant level by averaging across all valid days, yielding the mean number of minutes per hour bin for each intensity level. This procedure resulted in 72 subject-level features per participant (24 post-wake hour bins \(\times\) 3 intensity levels). Time periods occurring after the end of the nocturnal in-bed interval used to derive sleep efficiency were not considered part of the physical-activity exposure window. However, to preserve a fixed 24-hour feature length across participants, hour bins that fell entirely after bedtime were assigned zeros for all three intensity categories.

Calculation of sleep efficiency

In this study, sleep efficiency (SE) was calculated using equation (1) as a representative indicator of sleep. SE refers to the ratio of actual sleep time to total time spent in bed and is widely used as a simple, objective index of sleep continuity and sleep quality. Clinical insomnia guidelines and sleep-medicine texts commonly describe SE values of approximately 85% or higher as normal or satisfactory, whereas SE below 85% is regarded as indicative of clinically significant sleep disturbance or insomnia4,5,17. For example, guideline documents and expert consensus statements often use SE < 85% as a criterion for impaired sleep continuity and as a treatment target in cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia, with desired post-treatment SE in the 85% range4,5. Accordingly, in this study we categorized sleep quality into sufficient (good) and insufficient (impaired) using an SE threshold of 85%, aligning our definition of “impaired” sleep with established clinical practice and prior epidemiologic studies.

Participant classification based on Acrophase

This study primarily focused on Process S, one component of the Two-Process Model that describes sleep homeostasis, to analyze the relationship between physical activity and sleep. Because circadian rhythms also exert a strong influence on sleep onset and maintenance, it was necessary to account for circadian phase in order to interpret the effects of Process S more recisely23,24. To approximate each participant’s circadian phase, we derived a relative acrophase measure from wrist blue-light exposure. Blue-light counts were first converted to 1-minute epochs and restricted to the period between the recorded wake-up time and subsequent bedtime for each participant. Within this post-wake interval, we then identified the clock time at which blue-light exposure reached its maximum value; the elapsed time (in hours) from wake-up to this maximum was defined as that participant’s relative circadian phase (acrophase). Based on this acrophase estimate, participants were categorized into three circadian groups: Early (0–3 hours after waking), Middle (3–6 hours), and Late (6–9 hours). These 3-hour windows were chosen to distinguish earlier and later timing of daytime light exposure while maintaining sufficient sample size and interpretability within each group. Cases in which the estimated acrophase occurred more than 9 hours after waking were excluded from the analysis, because such extreme delays were unlikely to reflect typical entrained circadian rhythms and were judged to represent abnormally delayed timing22.

Building machine learning model

In this study, we used XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) to predict sleep efficiency based on physical activity and circadian rhythm characteristics. XGBoost is known to be a suitable algorithm for sleep research as it provides high predictive performance and efficiency, and can avoid overfitting through missing value handling and normalization techniques13,25. It is particularly useful for analyzing the interaction between sleep efficiency and activity data, as it can effectively model complex nonlinear relationships26,27. RandomizedSearchCV was utilized for hyperparameter optimization of the XGBoost model, with a total of 50 combinations randomly extracted for exploration. The hyperparameter search targets included seven items: maximum tree depth (3–15), minimum sample size for leaf node splitting (1–9), sampling rate (0.6–1.0), learning rate (0.001–0.2), and boosting iteration count (100–500). Model training and validation were performed by dividing the entire data into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) sets.

SHAP(SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis

To evaluate the effect of physical activity on sleep by time of day and intensity, we applied SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis. SHAP is a tool that makes the complex prediction process of machine learning models interpretable, enabling quantitative evaluation of the marginal contribution of each feature to the prediction26,28. As artificial intelligence technology is increasingly applied to fields such as medicine, health, and biosignal analysis, the demand for interpretability and transparency of predictive models is growing. This is particularly essential for understanding predictions in medical data and providing clinically interpretable insights29,30. Additionally, the SHAP summary plot ranks the importance of each feature in the model and shows whether a specific feature had a positive or negative impact on the prediction. SHAP values were calculated for a total of 72 input variables (1-hour intervals \(\times\) 3 activity intensities (minutes)), and the top approximately 20 variables were extracted and visualized in the summary plot until the cumulative sum reached 80 The SHAP summary plot visualizes the SHAP values for each variable by sample, simultaneously expressing the direction and magnitude of the variable’s predictive contribution. The horizontal axis represents the SHAP value, indicating the extent to which the variable increases (right) or decreases (left) the predicted value, while the vertical axis represents the variable name. Each point represents a single sample, and the color of the point indicates the actual value of the variable in that sample (red: high value, blue: low value). Therefore, if the red points for a variable are concentrated on the right side, it means that high values of that variable contributed to improving sleep efficiency. Conversely, if the blue points are skewed to the left, it means that low values contributed to predictions associated with reduced sleep efficiency (Fig. 2).

Results

Model performance

When activity data for all intensities was provided for all three groups, it was found to be the most accurate in predicting sleep efficiency. Compared to when only a single intensity was used as an input variable, it showed better results in terms of F1-score in most cases (Table 2).

In the Early group, ALL (including all features) had an accuracy of 0.848 ± 0.031, recall of 0.936 ± 0.029, precision of 0.870 ± 0.037, specificity of 0.606 ± 0.133, and F1 score of 0.901 ± 0.019, showing the highest F1 score. Among the single-intensity models, MPA-only achieved the highest recall (0.942 ± 0.037), but specificity was low at 0.489 ± 0.133. VPA-only had a slightly lower recall (0.914 ± 0.039) but the highest specificity (0.627 ± 0.110). In the Middle group, the F1-score for ALL (all features included) was 0.867 ± 0.020, and among the single intensities, VPA-only showed the highest Accuracy (0.837 ± 0.035), Precision (0.864 ± 0.050), specificity (0.771 ± 0.102), and highest F1 (0.869 ± 0.026). In contrast, LPA-only had the highest recall (0.904 ± 0.036) but relatively low precision and specificity. In the Late group, the ALL (all features included) model showed excellent balanced performance with Accuracy 0.840 ± 0.029, Recall 0.915 ± 0.040, Precision 0.861 ± 0.043, Specificity 0.682 ± 0.121, and F1 0.885 ± 0.019. Among single intensities, MPA-only recorded the highest F1-score of 0.887 ± 0.032, and VPA-only showed the highest specificity of 0.702 ± 0.101.

SHAP analysis results

For each group (Early/Middle/Late), SHAP values were computed for all 72 features (1 hour \(\times\) 3 intensities), and the \(\approx\)20 variables explaining approximately 80% of the cumulative contribution were summarized (Figs. 2, 3, 4).In the Early group, positive contributions were concentrated in late-morning LPA windows (8 to 12 h; LPA_9h, LPA_12h, LPA_10h, LPA_8h), where high-activity samples clustered on the right side of the SHAP axis.The VPA window exhibited a bidirectional pattern with broader dispersion, particularly at 4 hours, 7 hours, and 12–13 hours. Overall, the initial window after waking (1–3 hours) primarily showed negative values regardless of intensity, while the 8–12-hour LPA accounted for most of the positive values within the top approximately 80% cumulative contribution (Fig. 3).

The early group consisted of a majority of upper variables in the 8–12h interval after weathering, with LPA_9h and LPA_12h at the top. These variables shifted the prediction in a positive (+) direction as activity increased. In contrast, LPA immediately after weathering (1h) acted in a negative (−) direction as the value increased. High-intensity (VPA) generally had a dominant negative (−) influence (VPA 11 h, 3 h, 14 h, 5 h, etc.), while some windows (VPA 4 h, 7 h, 12 h, 13 h) exhibited a nonlinear pattern where the sign changed depending on the magnitude of the value.

In the Middle group, positive contributions were concentrated in mid-day LPA windows (12 to 14 h and 8 to 10 h), where high-activity samples clustered on the right side of the SHAP axis. By contrast, VPA windows showed a bidirectional pattern with wider dispersion–especially 12 to 15 h and 7 h–indicating greater between-subject heterogeneity, and MPA at 7–9 h entered the top set with mixed signs. Overall, early post-wake windows (1 to 3 h) were predominantly negative across intensities, whereas later-day LPA accounted for most of the positive mass within the top approximately 80% cumulative contribution (Fig. 4).

The middle group showed a clear positive contribution as the afternoon LPA (12–14h, 9 h, 8 h, 5 h, etc.) increased. In contrast, both VPA and LPA immediately after waking up (1–3h) were negative. VPA (7 hours, 12–15 hours) was highly significant, but its direction varied depending on the value, showing a pronounced nonlinearity. MPA (7–9 hours) was included in the top tier, but its contribution direction was mixed.

In the Late group, positive contributions were concentrated in LPA windows at 12–15 h (LPA_12h, LPA_13h, LPA_15h, LPA_11h, LPA_14h), and LPA_1h was also positive. Negative contributions dominated for VPA_10h and VPA_1h and for MPA_14h. VPA windows showed bidirectional patterns with wider dispersion–especially 7 h and 12–15 h–indicating greater between-subject heterogeneity; MPA_1h and VPA_6h likewise exhibited mixed signs. Overall, later-day LPA accounted for most of the positive mass within the top \(\approx\)80% cumulative contribution, whereas early post-wake MPA/VPA remained largely negative (Fig. 5).

The late group shap summary plot showed a delayed LPA window (12−15 h) with a positive (+) contribution, and LPA_1h also showed a positive (+) contribution, indicating heterogeneity at the initial stage in contrast to the early/middle stages. Moderate to high intensity (MPA_14h, VPA_10h, VPA_1h, etc.) generally showed a negative (−) contribution. Some variables, such as MPA_1h and VPA_6h, showed high significance and nonlinear patterns.

Discussion

This study aimed to elucidate the association between physical activity and sleep based on the theoretical concepts of the Two Process Model. We integrated actigraphy and blue light exposure data collected from HCHS/SOL and MESA and performed XGBoost–SHAP analysis that simultaneously considered relative time after waking, activity intensity, and individual circadian phase. The results showed that the model integrating all intensity features (ALL) demonstrated overall higher or at least equivalent performance compared to the model using a single intensity level across all three groups (Early/Middle/Late) (e.g., Early F1=0.901±0.019; Late F1=0.885±0.019). This quantitative performance demonstrates that combining time, intensity, and individual phase information stabilizes predictive power, overcoming the existing limitation that it is difficult to capture subtle differences using only a total activity perspective. Additionally, the high accuracy of 0.8 or above suggests that physical activity plays an important role in sleep efficiency and enables more accurate prediction of the effects of activity on sleep. In addition, this study utilized SHAP-based explanatory analysis to quantitatively demonstrate how “when and at what intensity” are associated with sleep efficiency, beyond simply “how much.” Across the three groups (Early/Middle/Late), low-intensity physical activity (LPA) during the mid-to-late time window was associated with an increase in sleep efficiency (positive contribution), while moderate-to-high-intensity physical activity (MPA/VPA) immediately after waking (1–3 hours) was associated with a decrease in sleep efficiency (negative contribution) (Figs. 2, 3, 4). In addition, the “optimal time window” for LPA was observed to gradually shift from Early (approximately 8–12 hours) to Middle (approximately 12–14 hours) to Late (approximately 12–15 hours), indicating that the optimal time window varies depending on the individual’s phase, even for the same activity. Nonlinearity (mixed contribution signs and saturation with increasing activity levels) was observed in some indicators, suggesting that effects may diminish or reverse direction beyond a certain intensity or time window. This methodology not only resolves some inconsistencies observed in previous studies but also paves the way for personalized intervention strategies targeting sleep disorders. This study demonstrates how specific levels of physical activity can improve sleep efficiency and emphasizes the potential of activity-based non-pharmacological interventions as an alternative to existing pharmacological therapies associated with dependency and side effects. In addition, this study sought to overcome the limitations of previous studies and analyze the relationship between physical activity and sleep efficiency more precisely. Most previous studies focused solely on total daily activity levels or failed to adequately account for the interaction between circadian rhythms and physical activity. For example, studies such as Mitchell et al. (2016) and Atoui et al. (2021) failed to yield significant results regarding the relationship between physical activity and sleep efficiency, as they did not consider time-of-day activity patterns, thereby inadequately reflecting the impact on sleep efficiency. Additionally, Park et al. (2022) reported a low prediction accuracy of 0.69 using activity and light data. However, this study achieved a prediction accuracy of over 0.8 using an XGBoost classifier by modeling the effects of physical activity on sleep efficiency in a sophisticated manner, including the extraction of circadian rhythm characteristics through time-of-day physical activity and light exposure, through analysis that considered the interaction between sleep pressure and circadian rhythm based on the Two Process Model. This empirically demonstrated that accurate sleep prediction is possible through machine learning-based models. Additionally, through SHAP analysis, this study distinguishes itself from previous research by extending beyond the general perception that “moving more leads to better sleep” to provide precise behavioral strategies regarding when and at what intensity activities should be performed.

The SHAP technique also analyzed the impact of activity at different times of the day and found that the impact of activity varied by time of day, with many movements in the evening, especially 13 to 16 hours after waking, having a negative impact. On the other hand, activity in the first three hours after waking had a positive effect on sleep efficiency. Based on these results, it is possible to suggest the right activity habits to improve sleep quality. The use of SHAP analysis further enhanced the interpretability of the machine learning model and provided quantitative insights into the interaction between activity timing and circadian rhythm parameters. This study used innovative methods to overcome the limitations of previous studies and more accurately analyze the relationship between physical activity and sleep efficiency. Previous studies have mostly focused on the total amount of activity per day, or have not fully accounted for the interaction between circadian rhythms and physical activity. For example, studies such as Mitchell et al. (2016) and Atoui et al. (2021) did not find significant results in the relationship between physical activity and sleep efficiency, and did not fully reflect the impact on sleep efficiency because they did not consider activity patterns by time of day2,10. In addition, Park et al. (2022) reported a low prediction accuracy of 0.69 using activity and light data11. However, through an analysis that considers the interaction of sleep pressure and circadian rhythm based on the Two Process Model, this study comprehensively models the effect of physical activity on sleep efficiency, including the extraction of circadian rhythm features by time of day physical activity and light exposure, and achieves a prediction accuracy of 0.89 using the XGBoost classifier, empirically demonstrating that accurate sleep prediction is possible using machine learning-based models. In addition, the SHAP analysis can clearly identify the impact of time-of-day activity on sleep efficiency, which differs from previous studies in that it visually represents the impact of activity on sleep at a specific time of day.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis sample consisted mainly of adults (particularly those aged 45–84 in MESA, with some HCHS/SOL participants included), so caution is needed when generalizing the results to adolescents, the elderly, the very elderly, shift workers, and others. Second, physical activity is limited to the intensity \(\times\) time (min) metric derived from Actiwatch-based CPM (counts per minute), which does not directly reflect activity type (aerobic/strength), context (indoor/outdoor), or physiological responses (HR/HRV). Third, sleep indicators focused on sleep efficiency (SE) using a binary classification (85% cutoff), failing to adequately consider sleep latency, fragmentation, and stage (REM/NREM) information. Fourth, due to the observational study design, residual confounding and reverse causality (the influence of sleep status on activity) cannot be ruled out, and circadian phase estimation also relies on the acrophase of wrist blue light exposure as a proxy indicator, excluding biological markers such as DLMO. Therefore, future studies should expand to diverse populations such as adolescents, shift workers, and patients with sleep disorders, perform cross-cohort external validation, combine accelerometers with HR/HRV, GPS, and environmental light (corneal illuminance) to refine activity types and contexts, and include melatonin indicators to improve the accuracy of phase estimation. Additionally, sleep outcomes should be expanded to include not only SE but also latency, fragmentation, stages (REM/NREM), daytime sleepiness, among other continuous/multidimensional indicators. Causal effects of time \(\times\) intensity \(\times\) phase should be validated through longitudinal design/micro-randomization (RCT) and targeted trial emulation, and sensitivity analysis of window size, intensity cutoff, and model settings, as well as fairness/subgroup performance evaluation, should be systematized to enhance clinical applicability.

Conclusion

This study investigated the relationship between sleep and physical activity and quantitatively interpreted the relationship between activity intensity by time of day and sleep efficiency, thereby empirically demonstrating the effect of “when and at what intensity” physical activity is performed on sleep, rather than simply the amount of activity. In most models, physical activity data alone could predict sleep efficiency to a certain extent. Low- and moderate-intensity activities had a positive effect on sleep efficiency at gradually delayed time points based on blue light exposure, while high-intensity activities consistently showed a negative effect at specific time points. This suggests that the effects of physical activity may vary depending on the interaction between an individual’s circadian rhythm and the timing and intensity of activity. These results go beyond the simple notion that “the more you move, the better you sleep,” providing evidence that the timing and intensity of activity can be decisive for sleep, and laying the theoretical foundation for more precise personalization of existing sleep hygiene guidelines. This study challenges the common perception that simply increasing activity levels improves sleep quality and empirically demonstrates that the effects of activity can vary depending on the timing and intensity of activity, as well as an individual’s circadian rhythm. Particularly, the study analyzes the effects of activity based on relative time intervals (e.g., 9 hours after waking) rather than absolute time intervals (e.g., 9 a.m. 8 p.m.) but rather relative time intervals based on wake-up time (e.g., 9 hours after waking up) provides a basis for more precise interpretation of existing sleep hygiene guidelines. Additionally, the exploration of optimal activity time intervals based on individual circadian phases using blue light exposure timing demonstrates the potential for developing circadian rhythm-based personalized sleep intervention strategies. Furthermore, this study empirically demonstrated that physical activity for sleep improvement is not sufficient with mere exercise recommendations or increased activity levels alone; rather, performing activities at times aligned with an individual’s circadian rhythm can be a core strategy. These results can serve as meaningful foundational data not only in terms of theoretical contributions but also in practical applications.

Data availability

This study utilized data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), including its Sleep Ancillary Study, and the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). The MESA Sleep dataset is available for research purposes upon application and approval through the MESA website (https://www.mesa-nhlbi.org/). The HCHS/SOL dataset is available through the Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) under accession number phs000810.v1.p1. Researchers must comply with the respective data use agreements and ethical guidelines provided by the MESA and HCHS/SOL study teams. The authors are unable to share these datasets directly.

References

Sharma, S. & Kavuru, M. Sleep and metabolism: an overview. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 270832 (2010).

Atoui, S. et al. Daily associations between sleep and physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Rev. 57, 101426 (2021).

Knutson, K. L. & Van Cauter, E. Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Annals of the New York Acad. Sci. 1129, 287–304 (2008).

Ree, M., Junge, M. & Cunnington, D. Australasian sleep association position statement regarding the use of psychological/behavioral treatments in the management of insomnia in adults. Sleep Medicine 36, S43–S47 (2017).

Morin, C. M. et al. Insomnia disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 1, 1–18 (2015).

Chattu, V. K. et al. The global problem of insufficient sleep and its serious public health implications. Healthc. (Basel) 7, 1 (2018).

Qiao, Y., Wang, C., Chen, Q. & Zhang, P. Effects of exercise on sleep quality in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sci. Medicine Sport https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2024.11.015 (2024).

Chesson, J., A. L. et al. Practice parameters for the nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. Sleep 22, 1128–1133 (1999).

Lang, C. et al. The relationship between physical activity and sleep from mid adolescence to early adulthood: A systematic review of methodological approaches and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Rev. 28, 32–45 (2016).

Mitchell, J. A. et al. No evidence of reciprocal associations between daily sleep and physical activity. Medicine & Sci. Sports & Exerc. 48, 1950 (2016).

Park, K. M. et al. Prediction of good sleep with physical activity and light exposure: a preliminary study. J. Clin. Sleep Medicine 18, 1375–1383 (2022).

Borbély, A. A. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol 1, 195–204 (1982).

Dijk, D. J. & Czeisler, C. A. Contribution of the circadian pacemaker and the sleep homeostat to sleep propensity, sleep structure, electroencephalographic slow waves, and sleep spindle activity in humans. J. Neurosci. 15, 3526–3538 (1995).

Lockley, S. W., Skene, D. J., Butler, L. J. & Arendt, J. Sleep and activity rhythms are related to circadian phase in the blind. Sleep 22, 616–623 (1999).

Mantua, J., Gravel, N. & Spencer, R. M. Reliability of sleep measures from four personal health monitoring devices compared to research-based actigraphy and polysomnography. Sensors 16, 646 (2016).

Åkerstedt, T., Hume, K. E. N., Minors, D. & Waterhouse, J. I. M. The meaning of good sleep: a longitudinal study of polysomnography and subjective sleep quality. J. Sleep Res. 3, 152–158 (1994).

Reed, D. L. & Sacco, W. P. Measuring sleep efficiency: what should the denominator be?. J. Clin. Sleep Medicine 12, 263–266 (2016).

Bild, D. E. et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 156, 871–881 (2002).

Zhang, G. Q. et al. The National Sleep Research Resource: towards a sleep data commons. J. Am. Med. Informatics Assoc. 25, 1351–1358. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy064 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep disturbances: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (mesa). Sleep 38, 877–888. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4732 (2015).

Redline, S. et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in hispanic/latino individuals of diverse backgrounds. the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189, 335–344 (2014).

Kemp, C. et al. Assessing the validity and reliability and determining cut-points of the actiwatch 2 in measuring physical activity. Physiol. Meas. 41, 085001 (2020).

Wahl, S., Engelhardt, M., Schaupp, P., Lappe, C. & Ivanov, I. V. The inner clock–blue light sets the human rhythm. J. Biophotonics 12, e201900102 (2019).

Khalsa, S. B. S., Jewett, M. E., Cajochen, C. & Czeisler, C. A. A phase response curve to single bright light pulses in human subjects. The J. Physiol. 549, 945–952 (2003).

Sahin, E. K. Assessing the predictive capability of ensemble tree methods for landslide susceptibility mapping using XGBoost, gradient boosting machine, and random forest. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1308 (2020).

Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.07874 (2017).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794, https://doi.org/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (2016).

Adadi, A. & Berrada, M. Explainable AI for healthcare: from black box to interpretable models. In Embedded Systems and Artificial Intelligence: Proceedings of ESAI 2019, Fez, Morocco, 327–337 (Springer Singapore, 2020).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. Explainable AI for trees: From local explanations to global understanding. arXiv preprint (2019). arXiv:1905.04610.

Zihni, E. et al. Opening the black box of artificial intelligence for clinical decision support: A study predicting stroke outcome. PLOS ONE 15, e0231166 (2020).

Funding

This work was funded by BK21 FOUR (Fostering Outstanding Universities for Research) (No.: 5199990914048), the Korea Medical Device Development Fund (Project Number: 1711196787, RS-2023-00255005), and the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C. conceived and designed the study; integrated the HCHS/SOL and MESA datasets; performed data preprocessing, model development (XGBoost), SHAP analyses, and statistical evaluation; and drafted the manuscript. Y.O. performed data preprocessing, generated figures and tables, and contributed to data visualization and manuscript formatting. C.P. assisted with data preprocessing, implemented parts of the analysis code/pipeline, and contributed to reproducibility checks. Y.K. provided domain expertise in sleep and circadian physiology, advised on study design and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. C.W. contributed to methodology for actigraphy/light exposure feature engineering and provided critical comments and revisions. S.D.M. (corresponding author) supervised the overall project, provided methodological guidance, coordinated revisions, and approved the final version. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choe, J., Oh, Y., Park, C. et al. Associations between daily physical activity timing and sleep efficiency revealed by explainable machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 45064 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32036-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32036-4